chapter seven

The Bonsai Saga

How the Bicentennial Collection Came to America

by Dr. John Creech

My first acquaintance with the art of bonsai was in 1947 when I joined the staff of the Division of Plant Exploration and Introduction of the U.S. Department of Agriculture (USDA) at Beltsville, Maryland. In 1898, Dr. David Fairchild established this USDA division for the purpose of sending plant explorers searching the world for new plants for American agriculture.

In a country with only the sunflower, blueberry, cranberry and pecan as native food crops, American agriculture is enhanced by food, feed and fiber plants from around the world. Since its inception, the division of Plant Exploration and Introduction has undertaken well over 200 plant hunting expeditions, and no region of the earth where indigenous crop plants exist has been overlooked.

In conjunction with the collecting of plants by the USDA, there must be facilities to receive introductions, document them, inspect them for pests and finally to grow the great numbers of plant accessions that are received. Seed introductions often went directly to USDA departmental plant breeders or were placed in storage, while collected living plants were required to be grown at Federal Plant Introduction Stations located in different climactic regions of the country.

The Federal Plant Introduction Station at Glenn Dale, Maryland was one such location. The Glenn Dale station served not only as a growing-on facility but also as a main quarantine station for plants normally prohibited from entering the United States. Thousands of valuable plant collections have passed through its greenhouses and nurseries on their way to researchers and nurserymen—the Glenn Dale station functioned as a kind of “Ellis Island” for plants.

One of my first responsibilities was to spend two days each week at the Glenn Dale station to oversee plant distribution and to conduct propagation research. Among the plants being held in quarantine when I arrived at Glenn Dale was a bonsai specimen (either cherry or apple) that had been presented to a high-ranking U.S. admiral by his Japanese counterpart after World War II. It had been in quarantine for about two years under the care of a longtime greenhouse attendant who was an expert at grafting and other methods of propagation. His main goal was to grow plants to perfection before their release, and he took particular pride in this accomplishment. When the day came to release the bonsai, a young naval aide to the admiral came to collect the admiral’s plant. It was wheeled out in its diminutive form in fine condition but sporting a new stout branch about four feet high. The proud caretaker commented, “I guess I showed them how to grow a plant properly!” He was actually not far from the truth because bonsai specialists often allow a vigorous shoot to grow as a way to rehabilitate a weakened specimen. So much for bonsai in quarantine at that time.

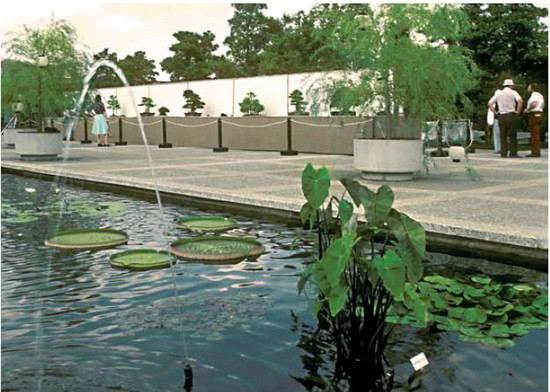

Some bonsai are moved around within the museum. Here, the Japanese Hemlock (Tsuga diversifolia) given by Princess Chichibu is featured in the lower courtyard.

A Ginkgo (Ginkgo biloba), in training since 1926, was part of the Bicentennial Gift. Ginkgo trees of every size are renowned for their brilliant golden fall foliage.

Bonsai and Penjing in the U.S. before the Bicentennial

Prior to the enforcement of stringent plant quarantine regulations in 1919, plants entered the United States with few quarantine safeguards and soil was permitted. This included bonsai—or “dwarf trees for table decorations” as one Japanese exporter described them. Japanese bonsai were frequently displayed at national exhibitions but they were often regarded as curiosities.

The famous Boehmer nursery and exporting firm that existed in Yokohama between 1882 in 1908 advertised bonsai in their “original pots” for three to fifty yen, according to shape, age and general attractiveness. There is a sketch in the 1899 catalog of a dwarf maple that was sold to HRH the Princess of Wales. It is likely that many wealthy American visitors returned from Japan with a bonsai or two, but only a few survived or were trained properly.

Perhaps the most successful introduction of bonsai into the United States during the early 1900s was by our ambassador to Japan, Larz Anderson, who was interested in all Japanese art forms. When Anderson returned from Japan in 1913, he brought at least 40 bonsai to Weld, his estate near Boston, Massachusetts, from Yokohama Nursery, the renowned Japanese successor to L. Boehmer and company. His collection was later donated to the Arnold Arboretum where it may be seen in fewer numbers today.

After the plant quarantine regulations went into effect in 1919, the importation of bonsai into the United States became much more difficult. In 1960, when Dr. George Avery, Director of the Brooklyn Botanic Garden, began to acquire new bonsai from Japan to add to the collection which was started in 1925, trees were bare-rooted and fumigated before release to the garden. This treatment almost always killed the plants.

For a time, the U.S. Department of Agriculture agreed to house some of the new bonsai acquired by the Brooklyn Botanic Garden in quarantine at the Glenn Dale station. Later on, bonsai were allowed to go directly into post-entry quarantine at the Brooklyn Botanic Garden, as long as they were free of insects and disease.

One such bonsai that the Brooklyn Botanic Garden acquired from Japan was a famous 900-year-old juniper called “Fudo,” which had been purchased in 1969 at considerable expense (perhaps $15,000) by a private donor. The soil had to be removed and the tree was fumigated to meet quarantine requirements. Unfortunately, the tree died as a result of the severe combined treatment. The tree’s death sent shockwaves through the Japanese bonsai community and demonstrated that it was fruitless to introduce bare-root conifer bonsai. The skeletal remains of “Fudo” are still preserved at the Brooklyn Botanic Garden for posterity but this sad event almost caused the Japanese government to oppose the Bicentennial Gift of bonsai.

The art of bonsai continued to be obscure in the United States until after the military occupation of Japan in 1945. Many of the U.S. military personnel, akin to the ancient Japanese samurai, began to acquire a taste for Japanese arts—especially bonsai. Although they were unable to bring plants home because of the quarantine laws, they did have the opportunity to meet many of the Japanese bonsai masters. On returning home they fell in with a few bonsai clubs that formed in various parts of the country, particularly California, Hawaii, New York and Washington, D.C. They purchased seedlings and deformed plants that nursery men would have discarded, and acquired trained plants from Japanese bonsai artists. We owe much to these early bonsai enthusiasts for expanding American interest in this enduring art of Japan.

Regarding the Chinese art of penjing, as stylized dwarf trees are known in that country, even fewer collections existed in the United States. I saw my first penjing in 1974 when I visited the People’s Republic of China as a member of the first National Academy of Sciences Plant Studies Delegation to China after World War II. There I was invited to the Lung-hua Nursery near Shanghai where trees, shrubs and flowers were grown for schools, public buildings and street plantings. However, the Lung-hua Nursery is noted chiefly for its collection of several hundred ancient specimens of penjing and as a training school for propagation, trading and culture of dwarf plants.

During this same visit, I had an opportunity to see the famous bonsai/penjing collection of Dr. Yee-sun Wu in Hong Kong, which was arranged by Colonel John Hinds (US Air Force), a prominent American bonsai enthusiast. The difference in artistic style between the Japanese and Chinese approach was striking—the Chinese style seems strong and severe in character as opposed to the more graceful and reflective style of the Japanese. The reluctance of the Chinese to permit plants regarded as national treasures to be exported, particularly without soil, meant that no penjing entered the United States for decades, except for the collection of several small penjing that were presented to President Nixon at the time of his historic visit to China in 1972.

A Japanese Wisteria (Wisteria floribunda) was one of the bonsai given to the U.S. in 1976, while other varieties are grown in the museum’s gardens.

Until the Bicentennial in 1976, mainly private clubs and amateur growers had advanced the art of bonsai in the United States. Except for the Brooklyn Botanic Garden and the Arnold Arboretum, public institutions were reluctant to develop bonsai collections. This was due to the lack of trained curators to maintain bonsai as well as the cost of plants relative to a fairly limited audience. Today, on the other hand, many arboreta have both a Japanese garden and a flourishing bonsai collection. These institutions have become the support facilities for the many bonsai organizations that have sprung up around the country, and the art has now acquired an international stature.

Plant Hunting in Japan

The 1955 Expedition

In the 1950s, Japan was still recovering from World War II and many bonsai nurseries that had struggled to maintain their collections throughout the war were still impoverished. But they continued to grow and train bonsai with the expectation that better times were coming. Little did they know at the time that bonsai would become such a popular international art form.

My introduction into the great game of plant hunting was to spend eight months as a USDA plant explorer in Japan in 1955. During that period, I was directed to collect samples of soybeans, rice, fruits, vegetables, and even a rare banana species (Musa liukiuensis) native to Okinawa, and to search for plants to be used in pharmaceutical research. The surprising bonus was that I was also authorized to collect ornamental plants. Japan is a treasure house of wild species that are exceptional landscape ornamentals, and Japanese nursery men have selected and improved them over the past ten centuries. Because there had been no serious collecting of ornamentals in Japan since Ernest Wilson of the Arnold Arboretum collected widely in Japan in the years before 1920, I had a gold mine opened to me.

Unlike ordinary governmental travelers, USDA plant explorers were given broad authorization to expend funds. This included hiring conveyances of all kinds (mules, carts, boats, etc.), purchasing necessary equipment, retaining guides importers, and conducting all activities essential to complete the fieldwork. Of course, all such expenditures had to be accounted for, and it must have caused the auditors considerable concern when they received payment vouchers with a thumbprint instead of a signature!

During this first year spent in Japan, I was able to collect over 800 individual lots of seeds, cuttings and small plants that I would regularly ship back home through diplomatic and military air facilities. These collections were packed in sterile sphagnum moss and were flown directly to Washington, D.C., where they were inspected at the plant quarantine inspection house and sent immediately to the Glenn Dale station. Thus, the timeframe from collecting to greenhouse was only a matter of a few days—in sharp contrast to the months that it been required in earlier days when shipments went by sea.

During this 1955 exploration trip, I also became acquainted with bonsai culture in Japan, particularly azaleas as these were grown by specialists who were solely interested in the large-flowering Satsuki azaleas. The Japanese grew these gorgeous azaleas as potted plants, training them into fantastic shapes. Other growers concentrated on the so-called small-flowered Kurume azaleas for bonsai. Because azaleas are easy to ship bare-rooted, I acquired and shipped back to the United States quite a number of the leading varieties as potential garden plants. Many of these introductions are still in cultivation today.

One of my most constant companions during my 1955 trip to Japan was the distinguished horticulturist Kaname Kato (no relation to Saburo Kato, current Chairman of the Nippon Bonsai Association), who took me to countless Japanese nurseries and botanic gardens. He introduced me to many of the most outstanding examples of Japanese horticulture, particularly the fantastic array of azaleas, camellias, and a rich assortment of ornamental plants held in private collections. During train rides and evenings at small inns, Kaname Kato would describe the virtues of leading azaleas and take me to obscure growers of rare plants whom I otherwise would never have known. We became fast friends, and over the ensuing years we collaborated on the preparation of A Brocade Pillow, the English version of Kinshu Makura, a treatise on azaleas written in Japanese in 1692.

It was Kaname Kato who took me to the Yoshimura family bonsai nursery, Kofu-En, where I met Yuji Yoshimura for the first time. I later established a fine relationship with Dr. George Avery of the Brooklyn Botanic Garden, due to our mutual interest in Japanese horticulture. Then, I assisted with his efforts to bring bonsai from Japan, and he would invite me to visit the Brooklyn Botanic Garden on occasion to deliver lectures about my plant collecting experiences in Asia. Through this relationship I was able to add my recommendation that Yuji Yoshimura be employed to teach the art of bonsai at the Brooklyn Botanic Garden.

A Japanese Camellia (Camellia japonica (Higo Group) ‘Yamato-nishiki’), in training since 1875 and given in 1976, delights winter visitors to the museum with its colorful blooms.

Little did I realize in those early years of my acquaintance with Kaname Kato and Yuji Yoshimura they would play such an important role in the events that culminated in the Bicentennial bonsai collection.

The 1956 Expedition

I returned to Japan in the fall of 1956 under a new plant collecting program financed jointly by Longwood Gardens in Kennett Square, Pennsylvania and the USDA’s Agricultural Research Service. This time the mission was strictly to collect ornamental plants for the American nursery industry. Dr. Russell J. Siebert, Director of Long-wood Gardens, was a former USDA plant explorer and believed that ornamental plants deserved equal treatment with other economic crops. When this joint program was finally terminated in 1972, 13 ornamental expeditions to various parts of the world had been undertaken.

My 1956 expedition emphasized southern Japan because of the extensive array of broad-leaved evergreen species in many interesting localities that had not been visited for decades. One of our goals was to explore the remote Island of Yakushima, some 90 miles south of Kyushu. Yakushima is home to some 1,200 species found in higher elevations, including wild camellias, azaleas, hollies and other plants of considerable interest to the United States. Ernest Wilson visited this island in 1914, and considered it to be a plants man’s paradise.

When Kyuzo Murata, Curator of the Imperial Bonsai Collection, visited the bonsai in quarantine, he checked all of them, not just the Imperial Pine.

On its highest peak, Miyanouradake (6,348 ft. elevation), colonies of the important Rhododendron yakusimanum flourish. It was on Yakushima, along a boulder-strewn stream, that I collected seeds of the rare Lagerstroemia fauriei, a crapemyrtle that was destined to become the source of powdery mildew resistance in all of the northern hybrids developed by the late Dr. Donald R. Egolf of the U.S. National Arboretum. The cultivar “Natchez,” a superb white-flowered tree developed by Egolf, is now the most widely cultivated crapemyrtle because of its disease resistance and handsome cinnamon-color bark—both characteristics drawn from Lagerstroemia fauriei.

The season also coincided with the great autumn chrysanthemum exhibition where I was introduced to chrysanthemum bonsai. These popular exhibitions also featured large tubs of individual plants trained in precise pyramidal form with as many as 1,000 large ball-type flowers, as well as cascade displays reaching to seven feet and striking displays of historic figures dressed in live chrysanthemums. Growers from each exhibition assembled cuttings of the most highly recommended chrysanthemum varieties, and I arranged to pick them up in late December to carry them home personally. Many plant collectors prefer this approach as a guarantee that their precious cargo will arrive home safely. One spider-type chrysanthemum that I brought back, “Tokyo white,” was said to have grossed over $1 million in the nursery industry during its several years of popularity.

The 1961 Expedition

I returned to Japan in 1961 to continue exploration, this time in central and northern Japan. Seeking improved hardiness, the strip focused on the northern range of distribution for both wild and garden forms of our leading nursery species, including azaleas, camellias, hollies other broad-leaved plants and conifers. One important plant we discovered was the northern form of Juniperus conferta, the shore juniper that I named “Emerald Sea.”

A Bicentennial Gift

The Potomac Bonsai Association 1973 Spring Show

It was not until I became Director of the U.S. National Arboretum in 1973 that I gave serious thought to the possibilities that could result from my earlier encounters with the Japanese bonsai community. What triggered my interest was a meeting with the members of the Potomac Bonsai Association during their 1973 spring show held at the U.S. National Arboretum.

In the spring of 1973, the Department of Agriculture requested its various units to submit proposals for a Bicentennial program. I felt that the National Arboretum in our nation’s capital would be a splendid site for an educational display of the wealth of America’s agricultural crops, including ornamentals, in a series of demonstration exhibits. This was to be an elaborate project with several permanent features, including a National Bonsai Garden, because the art was gaining popularity across the country, and a National Herb Garden displaying medicinal, culinary, dye, fragrance and related plants. It was my hope that national plant societies would hold their meetings at the National Arboretum during the Bicentennial year.

This was an overly ambitious project but the various local plant clubs and societies that used the Arboretum were quite willing to support the idea. Because Congress had not funded a significant Department of Agriculture celebration in the Bicentennial, the Arboretum proposal went nowhere, and I was left to my own devices as to how the National Arboretum would participate in the festivities for our nation’s 200th birthday.

At the 1973 spring show of the Potomac Bonsai Association (PBA) at the National Arboretum, I discussed with John Hinds the possibility of obtaining a small collection of bonsai from friends in Japan for exhibition at the Arboretum. But how would we get the plants here safely? John suggested that the Air Force might be persuaded to fly the plants from Japan since they had regular cargo flights that often returned empty or with partial loads. Other members of the PBA quickly gave their wholehearted support to my idea of a possible bonsai collection at the Arboretum. But still, there were many problems to be solved.

Getting USDA Approval

As a first step, I approached Ivan Rainwater of the USDA plant quarantine agency to see if it would be possible to bring in a collection of bonsai and soil from Japan. There were many genera that were prohibited from entry (including cherry and apple) and, of course, the first answer was “no soil.” Our quarantine officials had not forgotten the disastrous importation of cherry trees in 1910 that were so badly infested with unwelcome pests that 2,000 trees had to be burned within sight of the Washington Monument.

However, Rainwater had been the quarantine officer in Hawaii when I went there in 1962 to visit the botanic gardens and we become good friends. Fortunately, he had been transferred to the plant quarantine facility in Hyattsville, Maryland. He gave me approval to go ahead, with my assurance that the plants were going to detention in the quarantine houses at Glenn Dale for a year and be subject to rigorous periodic inspection for possible insects in the soil or diseases. This USDA approval to import bonsai with their soil was an exceptional departure from quarantine regulations. Nevertheless, it seemed to be a small risk because we agreed at the time that the bonsai would not leave the Arboretum once they were released from quarantine.

Nippon Bonsai Association’s Reply

With this concession, I wrote to Kaname Kato on May 11, 1973, and asked whether, in light of the celebration of our 200th anniversary of the United States in 1976, he thought it would be possible for the government of Japan or some representative organization to make a presentation of a bonsai collection as a symbol of our mutual admiration for living plants. I added that I needed some assurance before I broached the subject with Mr. Talcott Edminster, our Agricultural Research Service Administrator, and loyal supporter of the Arboretum.

Back came a letter from Kaname Kato stating that the President of the Nippon Bonsai Association, Mr. Nobusuke Kishi (a former Prime Minister), was personally very agreeable and willing to explore the idea. I approached Mr. Edminster informally and showed him Kato’s letter. He gave his approval to go ahead and assured me that, if the plan were successful we could build a viewing pavilion at the U.S. National Arboretum.

In early June 1973, Kaname Kato met with the directors of the Nippon Bonsai Association (NBA) at the Satsuki (azalea) bonsai show. The NBA directors agreed to accept my request, stating that we “will be glad to send bonsai to your Arboretum to celebrate the 200th anniversary of the United States.” From then on, my main contact with NBA was Nobukichi Koide, President and Director of the NBA.

At this point, I could only maintain my composure by reminding myself that my predecessor, David Fairchild, had found himself pretty much in the same boat working both ends from the middle when he acquired the flowering cherries that grace the Tidal Basin in Washington, D.C.

Although no longer living, this azalea (Rhododendron ‘Shi-o’) was one of five Satsuki azalea bonsai from the 1976 Bicentennial Gift, shown blooming profusely in quarantine.

A Chinese-quince (Pseudocydonia sinensis), in training since 1875, bears large fruits in spite of its small size.

Support from the ABS and BCI

Other than the members of the PBA, particularly John Hinds and Jim Newton, the American bonsai world was unaware of our plans to bring a bonsai collection to the National Arboretum. Fortuitously, both the American Bonsai Society and Bonsai Clubs International were to meet for a joint Bonsai Congress in July 1973 in Atlanta, Georgia. John Hinds spoke to the presidents of the two societies and the congress chairman, and they blocked out 10 minutes at the main banquet so I could put forth the concept of a National Bonsai Center at the U.S. National Arboretum. Among those attending the congress was Yuji Yoshimura, who had expressed earlier his dream that the richest nation in the world should have a national bonsai collection.

Following my presentation to the congress, some members of the audience were skeptical about the realistic possibilities of a national bonsai collection. After all, since neither the Arboretum staff nor I had any experience with bonsai, how would we manage such a bonsai collection? Nevertheless, both Dorothy Young, President of the American Bonsai Society, and Beverly Oliver, President of Bonsai Clubs International, signed a resolution dated July 21, 1973, extending wholehearted support for the establishment of a national bonsai collection at the National Arboretum.

This action was an important step since I was then able to advise my Japanese colleague, Kaname Kato, of the support of both the leading bonsai societies in the United States as well as of Yuji Yoshimura. I also informed our Agricultural Attaché at the American Embassy in Tokyo, David Hume, of my intentions and the status of our plans. I had developed good relationships with our embassy staff in Japan during my several visits, and explained the benefits to U.S./Japan relations if we were to succeed in this endeavor. Hume was enthusiastic about the project and expressed his support.

Logistical Obstacles

With the USDA and the American bonsai societies on board, it was now time to turn attention to the logistics of the plan. Mr. Edminster, the ARS Administrator, told me that there would be only limited funds to construct a bonsai pavilion to house the collection. There was a dollar limit on construction without congressional approval, and he could not go to Congress to obtain a special appropriation because of higher departmental priorities. Nevertheless, I was quite happy to work within the funding limitations he could make available.

I was now able to advise the State Department that plans for a major bonsai gift from Japan in commemoration of the Bicentennial were progressing rapidly. John Hinds, Jim Newton and I met with the Cultural Affairs staff of the State Department to explain that, while we had assurances that the bonsai gift from Japan was a reality there still was the matter of transporting the plants from Japan safely. We expressed our hope that the Department of Defense might be persuaded to provide space on their cargo flights from Japan.

Hinds, now the Director of Community Relations for the Air Force, was in a position to exert his influence. In October 1973, he drafted a memorandum to the Assistant Secretary of Defense and recommended that the project be given serious consideration on the basis that it would help our relations with Japan considerably. In response to Hinds’ memorandum, I received a letter from the Department of Defense asking for a specific request. With approval from my own agency, I wrote to the Deputy Assistant Secretary of Defense, outlining our needs, justification and everything else I could think of to convince them of the significance of the gift. The response was not at all encouraging. Questions were raised about using defense resources for non-defense traffic, about obtaining certification that commercial transportation was unavailable and other similar roadblocks. But the letter did state that, when the specific request was made, possible exceptions to governing restraints would be considered.

A Visit with Henry Hohman

A great boost for the project came in September 1973 when I learned that Yuji Yoshimura was to put on a demonstration of bonsai training at the Brookside Gardens, Wheaton, Maryland. This provided an opportunity to solidify Yuji’s support for having a national bonsai collection at the National Arboretum, a place he had never visited. So I persuaded him to come to the National Arbor-etum to discuss the bonsai matter and perhaps give a demonstration. Yuji agreed and indicated he wanted to use a Japanese boxwood for this program. I knew just the place to find the right specimen.

Henry Hohman was the owner of Kingsville nursery, Kingsville, Maryland, and one of those early plantsmen who really knew plants. I first met Henry in 1947 because his nursery was one that received and tested plant introductions that the USDA distributed regularly. He could be a difficult character and was reluctant to deal with those who were not serious plants people. Among the many introductions Henry evaluated, he was particularly interested in broad-leaved evergreens and had an extensive collection of the Japanese boxwood (Buxus sempervirens).

It was out of Henry’s boxwood collection that the popular “Kingsville Dwarf” cultivar was selected. Some of these were astonishingly aged specimens, probably up to 50 years old. I arranged for a visit to Kingsville Nursery with Yuji to see what we could find. Bonsai artists Marion Gyllenswan, John Hinds, Jim Newton and Clifford Pottberg came along.

At this time, Henry was desperately ill with cancer and was generally not receiving visitors to the nursery. But he graciously made an exception for us. After a general tour of the nursery, Yuji began to inspect various box plants but none satisfied him. Finally, Henry said he had some special plants around his residence and asked if Yuji would like to see them. There Yuji found a beautiful, compact plant which was just what he wanted, and Henry promptly had it dug and burlapped. This plant was a propagation of one of the original Kingsville dwarf box plants that Henry had obtained in 1923.

Yuji Yoshimura worked on a Kingsville Boxwood (Buxus microphylla ‘Compacta’), a plant prized for its small leaves and slow growth.

John Hinds had researched the origin of the Kingsville dwarf boxwood. It was discovered in 1913 as a sport by Mr. Sam Appleby, who lived a few miles north of Kingsville. Mr. Appleby nurtured the sport and by 1923 had ten plants. He died in 1923, which was the same year that Henry established his nursery. Henry knew about the ten little “Kings” and acquired them that same year. He was aware that these extremely dwarf plants would never be cost-effective nursery stock—they were too slow-growing and the stems were too brittle. Despite these drawbacks, Henry continue to propagate the material and sometimes sold specimens to wealthy estate owners who used them as dwarf hedge material in their formal gardens.

After a sad farewell, since Henry was in considerable pain, we returned to Washington. That evening at Brookside Gardens, Yuji entertained a small audience with his masterful techniques. He could be an amusing character, and began his pruning on this well-branched plant by asking the audience: “Should I clip this branch? Or, how about this one?” By the time he had reduced the boxwood to practically a skeleton, one elderly lady in the audience explained, “Oh dear. He’s killing the plant!” But, of course he really was just establishing the basic structure for the future training of the boxwood as a bonsai.

From then on, it was Bob Drechsler who cared for this first one of the many bonsai to go into the American collection at the National Arboretum. After this demonstration, Yuji seemed more convinced than ever that we could succeed in obtaining a Bicentennial gift of bonsai from the Japanese.

Support from Colonel Hinds

As 1973 came to a close, I continued exchanging letters with my friend, Kaname Kato, and with Mr. Koide of the Nippon Bonsai Association to determine what was happening on the Japanese side. Apparently they were appealing to the Japanese government and the semi-private Japan Foundation for financial support. While the NBA was totally behind the idea of a Bicentennial gift of bonsai to the United States, I was advised that it was too late for the project to be included in the government’s 1973 budget, but there was hope that it could be included in the 1974 budget. I had, of course, already convinced my own administration that we were going to receive a bonsai collection and that we should go forward with our plans for a pavilion to house the plants.

It was also unsettling that, in early 1974, we still had no answer on the use of an Air Force aircraft. John Hinds, however, remained optimistic the transport would be available, knowing that planes often came back from Japan with little or no cargo. I was not so certain, but there was no turning back. John decided to take the transportation matter to Air Force Lieutenant General Maurice Casey, who was the most senior logistics officer in the Department of Defense. General Casey was on the staff of the Joint Chiefs of Staff where he was the “final word” on such logistics matters. Col. Hinds had known the general for a number of years, and they had a good working relationship.

Casey told Hinds that he appreciated the public relations benefit to the Air Force if that service flew the trees from Japan. He was concerned, however, that if the Air Force shipped the trees, the commercial airlines might lodge a complaint with Congress. At that time, the airlines were still up against high fuel costs caused by the 1973 energy crunch and wanted to maximize the use of their airplanes to increase revenue. Still, everyone hoped that the American Embassy in Japan would use its powers of persuasion in Washington to further our cause.

In February 1974, our stalwart supporter, Hinds, arranged to go to Japan for a major bonsai exhibit. He carried credentials from the American bonsai societies to speak on behalf of the bonsai project. I wrote our Agricultural Attaché in Tokyo alerting him to John’s visit. Dorothy Young also went to Japan for the bonsai exhibition and spoke eloquently at the meeting about our plans. Yuji had written to his brother, Kanekazu Yoshimura, explaining that Hinds was coming to Tokyo to help emphasize the sincerity of the United States’ position in moving forward with the bonsai project. The younger Yoshimura took Hinds in tow for the entire week of the Ueno Park bonsai exhibition, introducing him to the Nippon Bonsai Association officials and senior bonsai owners.

As it happened, John was acquainted with the senior editor of the U.S. military newspaper, Stars and Stripes, which had its head office in Tokyo, and the editor agreed to assign a reporter/photographer team to explore a story about his mission. John told Kanekazu Yoshimura that there was the possibility of a feature story about the mission, including photographs of bonsai personalities at the exhibition. Within hours Yoshimura had permission from the Nippon Bonsai Association to take photographs at the exhibition, and two or three days later a Stars and Stripes photographer/reporter team was posing Hinds and Yoshimura next to a 250-year-old Juniper. NBA’s granting of permission to do this sort of thing represented a rare and generous gesture, for traditionally they strictly enforced a “no photography” policy during their exhibitions. Before he left Japan, the Stars and Stripes printed a feature story headlined “Colonel Turns Bonsai Diplomat.”

On his way home, John stopped in Hong Kong to meet with Dr. Yee-sun Wu, a prominent Chinese banker and owner of a famous penjing collection. He had advised Dr. Wu much earlier about our plans for a national collection at the National Arboretum, including the concept of having Japanese, Chinese and American trees. While Wu was impressed with the concept, he hoped that the collection would be located in California....

On their return, both John and Dorothy reported that the Nippon Bonsai Association was fully committed to assembling a first-class collection of bonsai but the negotiations for funding were moving very slowly. Meanwhile, at the Arboretum I began to work informally with architects on plans for a pavilion but could go no further until we had the collection secured. I wrote to Mr. Koide of the Nippon Bonsai Association, assuring him of my complete confidence in his efforts and that he could count on our fulfilling our part of the agreement.

The bonsai in the Bicentennial Gift on view at the Nippon Bonsai Association’s headquarters in Ueno Park in Tokyo in March 1975.

Meeting the NBA Directors in Tokyo

In August 1974, I was part of the first delegation of biological scientists to go to the People’s Republic of China and had approval from Mr. Edminster to conclude the trip with a stopover in Tokyo to discuss the bonsai project. Things seem to be breaking just right because I never would have obtained approval for a trip to Japan solely for this purpose. I planned to have the artist’s sketches of the pavilion to show the Nippon Bonsai Association Directors, hoping that this would impress on them the seriousness of our intentions. In addition, Hinds had written to Dr. Wu about my trip and, as a result, I was invited to visit Wu’s penjing collection and discuss our plans for a national bonsai and penjing collection.

While in China, we visited many experimental stations, universities and other research facilities. At one point, I was able to break away to go to the Lung-hua Nursery near Shanghai where I had a chance to see and photograph their fabulous collection of penjing. When we returned to Hong Kong from China, I visited Dr. Wu’s impressive rooftop penjing garden, which was displayed under tight security. While the rest of the delegates returned home, I flew to Japan for my first face-to-face meeting with the Directors of the NBA since we had initiated the idea.

Earlier, the USDA had commissioned an artist’s sketch of our proposed bonsai pavilion and the sketch was completed while I was in China so I had no opportunity to see it. It was sent to our Agricultural Attaché in Tokyo and I picked it up just before the meeting. On September 27, 1974, I arrived at the offices of the Nippon Bonsai Association with my friend Kaname Kato and faced a group of “gentlemen of Japan,” solemn faced, mostly elderly and in a very formal setting around a table. None of them spoke English to any extent and we conversed through an interpreter, Miss Junko Arima. This young woman handled most of our exchanges over the next several months and exerted quiet but strong influence on the negotiations.

I explained to them the goals of our plan. It was to communicate by the gift of bonsai how the Japanese people appreciate nature through the enduring art of bonsai and to encourage a similar appreciation of this ancient art by Americans. I described how we planned to construct a pavilion at the Arboretum designed by Sasaki Associates, a famous Japanese-American architectural firm, to house the collection. I laid out the artist’s concept of the structure, which I had just seen for the first time.

After my Japanese friends saw the plan, they raised some serious concerns. They asked how the bonsai would flourish in the enclosed environment shown in the sketch, noting the apparent lack of air movement, sunlight and similar environmental needs. I quickly assured them that this was only an artist’s sketch and that we would deal with those problems when the architectural firm went to work.

Their main concern, of course, was to be sure that the precious bonsai would receive proper care at the Arboretum. To this question, I said we would appoint a trained curator for the collection and that bonsai specialists like Yuji Yoshimura and John Naka had expressed their willingness to serve as advisers and to assist in the training and maintenance of the collection.

Nippon Bonsai Association members preparing the trees for their dedication in 1976. Left to right: Eijiro Hiruma, Nobukichi Koide, Tsunekazu Nakajima and Saburo Kato.

Robert “Bonsai Bob”Drechsler, the first bonsai curator, caring for the trees of the Bicentennial Gift in quarantine in Glenn Dale, Maryland.

Inspecting the trees in quarantine in 1975, Dr. Creech accompanied Kyuzo Murata of the Imperial Collection and Hideo Chugun and Nobukichi Koide of Japan’s Nippon Bonsai Association.

With the Nippon Bonsai Association Directors’ questions seemingly answered to their satisfaction, there were smiles all around, and Mr. Koide spoke for the Directors saying that they would vigorously implore the various Japanese government agencies for funding. Then they asked when was the best time to send the collection and how would it be done. We all agreed that the early spring of 1975 would be the best time of year because the trees would be dormant and they would have to remain in quarantine for a full year prior to the 1976 Bicentennial. As for transportation, I explained that we were in contact with our Air Force officials and it was most certain the proper arrangements would be made for the safe journey to the United States. At this point it would have been improper to give a more definite answer and they seemed satisfied. I also assured them that the soil in the bonsai containers would not in any way be disturbed. This was an important point because they were aware that in previous shipments of plants the soil had been removed and they knew this was fatal to the bonsai.

So I departed with their pledge ringing in my ears that they would work earnestly to acquire the best bonsai. I, in turn, assured them that I would work equally hard to create a suitable home for these “children of Japan” at the National Arboretum. Before he departed, Mr. Koide mentioned that there would likely be a problem in choosing candidate plants. With so many famous bonsai growers, it was important that a great deal of diplomacy be used in the final selection. As it turned out, several former prime ministers as well as other high officials of the Japanese government would be listed as the donors of bonsai.

I later found out that the death of “Fudo,” the large Juniper whose soil had been removed when it was imported by the Brooklyn Botanic Garden from Japan, had apparently caused the Japanese Ministry of Foreign Affairs to initially oppose my request for a gift of living trees because Ministry officials thought the trees would die. This negative position was reversed after the Ministry realized that the bonsai to be given as a Bicentennial gift could be imported into the United States with their soil intact.

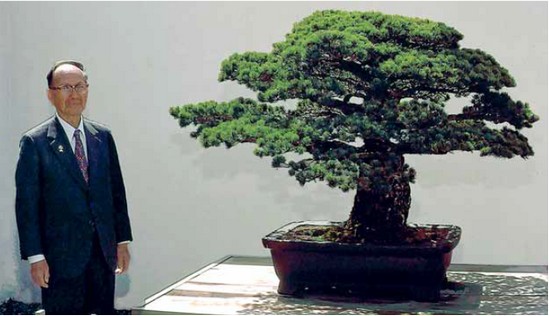

Saburo Kato, who today is the Chairman of the Nippon Bonsai Association and the most respected bonsai master in Japan, was working behind the scenes in those fateful early days. I later learned that Mr. Kato was instrumental in arguing our case before the Ministry of Foreign Affairs. He was able to convince Ministry officials that the bonsai for the Bicentennial gift would flourish in the United States, not only because they would be imported with their soil, but also because the NBA would show us how to care for the bonsai.

Choosing a Bonsai Curator

I returned home and reported the considerable degree of success in my mission to Mr. Edminster and to the bonsai societies. Up to this point we had not given serious consideration to selecting an Arboretum staff member to become the curator of the collection. Our senior horticulturist at the Arboretum, Sylvester “Skip” March, informed me that one of our senior technicians, Robert Drechsler would like to be considered for the position.

Bob was, without question, the right person for the job. He had worked for many years under the strict leadership of our renowned plant breeder Donald Egolf, and “discipline” was Don’s middle name. Bob was not only a well-trained horticulturist but had even been caring for the small collection of penjing that had been presented to President Richard Nixon during his visit to China. Thus, Bob was temporarily assigned the role of bonsai curator so that he could be prepared for the maintenance of the collection when it arrived at Glenn Dale. The year 1974 ended with everyone still awaiting the word that the Japanese collection was a fact.

The Gift Takes Shape

NBA Selects Bonsai and Suiseki

On January 30, 1975 Koide-san wrote that the Japanese government had funded the project. “Now,” he said, “we must move quickly to begin collecting bonsai from all over Japan so that they may be sent by the end of March.” A team from the Nippon Bonsai Association was then visiting bonsai growers throughout Japan to select the trees to be sent.

Fifty trees would be selected by the NBA—one for each of the American states. The tree selections were intended to express the broad range of plants that were cultivated as bonsai, as well as those of a venerable age and interesting habit. In addition, the gift would include a bonsai from the Imperial Household Agency collection and one each from Prince Takamatsu and Princess Chichibu. In all there would be 53 bonsai.

In addition, six selected viewing stones (suiseki) would be sent as an additional gift. The art of suiseki is an important element of bonsai displays. Suiseki are aesthetically pleasing stones that have been shaped over centuries by water torrents or other natural causes. They may be small enough to hold in one hand or so large that they require more than one person to lift them. They may have irregular white quartz veins running through black basalt to suggest a gushing mountain stream. They may resemble volcanic peaks or even a remote island rising from the sandy beach.

One of the most sought after suiseki is the “chrysanthemum stone” called kikkaseki. Mineral crystals formed on the face of the stone resemble an open chrysanthemum flower. This is of great significance to the Japanese as the chrysanthemum is the crest of the Imperial Family. Mr. Kiyoshi Yanagisawa donated the chrysanthemum stone presented to us. It was one of two such stones that he regarded as “husband and wife.” He said that while he was sad to be separating them he was proud that the “wife” would be happy in America.

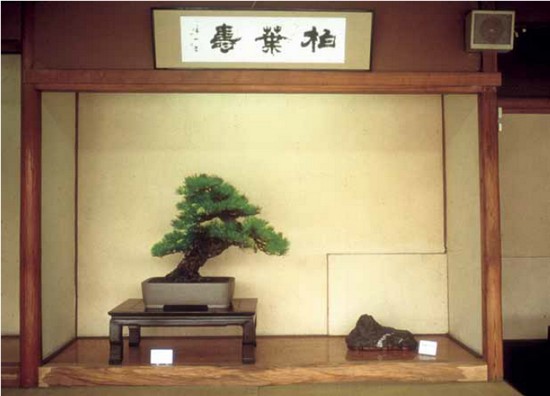

A 200-year-old Japanese Black Pine (Pinus thunbergii), chosen to reflect the age of the United States on its Bicentennial, was given the place of honor in the main tokonoma in the last Tokyo exhibit, accompanied by a Mountain Stream Stone, also part of the Gift.

5 When faced with a similar situation during the nineteenth century, our Navy was very accommodating when it came to bringing plants from foreign shores. All naval vessels were instructed to gather and bring home new plants from ports of call. In 1853, the Navy actually outfitted its sailing ship, the USS Release, specifically to travel to South America to collect cuttings of sugarcane and she brought back 1,000 cases to New Orleans.

A Disappointing Response

The ball was now in our court. Up to this point, I had pretty much been taking the lead, keeping Talcott Edminister and other officials well-informed. Our plant quarantine officer, Ivan Rainwater, who approved the list of species to be imported, and our Agricultural Attaché in Tokyo, Larry Thomasson, who would be our contact with the NBA, were also advised of the progress. I had brought the national Arboretum’s chief horticulturist, Skip March, into the picture earlier and now it was clear that he would play a significant role in coming events.

Thomasson cabled from our Tokyo Embassy that he had met with representatives of the Nippon Bonsai Association and that they were making final arrangements for outstanding bonsai candidates from all over Japan. He also said that a formal presentation ceremony in Tokyo was being planned for March 20, 1975, and that it was important for me or others from the Arboretum to attend the ceremony and fly back to the U.S. with the plants. Our most critical question at this juncture was whether the Air Force intended to transport the bonsai collection.

On February 27, 1975, our Defense Attaché in Tokyo cabled the Secretary of Defense requesting the transportation be authorized to transport the bonsai from Yokota Air Base to Andrews Air Force Base outside Washington.5 He pointed out that the extent of interest by the Japanese government in the donation to our Bicentennial, the estimated value of the collection ($5 million), and our own Embassy’s strong endorsement of the request. But the Defense Department finally turned down the request, despite vigorous pleas from our Defense Attaché. To my way of thinking, the Pentagon erred in judgment because having the Air Force transport the bonsai would have gone a long way towards improving the status of our military in Japan.

A Pan Am Purchase Order

Until this moment, I had not had the courage to tell our Japanese friends the transportation was in dire peril. Fortunately, after the Air Force declined our request to fly the bonsai to their new home, the USDA issued a purchase order to Pan American Airlines to transport the bonsai from Japan. In reality, Pan American Airlines was a more experienced carrier in handling such unusual shipments.

The estimated cost of the purchase order ($2,340) seemed unrealistic but it was an encouraging start. We had no estimate of the size of the individual trees or the manner of packing. Further, we had no plans as to who would accompany the trees and certainly were not aware of the many official requirements that would be faced. We were to learn that one just does not fly off with a valuable collection like this, particularly when the Imperial Household is involved.

Then another problem arose. The Japanese side and the American Embassy wanted me to attend the presentation station ceremony on March 20. But my agency had a system of approved travel plans and if your plan was not on the list there was no chance to be included. The only solution was a strange one. Skip March had access to employee dependent travel because his wife was an airline employee. We decided that he would fly to Japan in my place at no cost to the U.S. government. I so advised the Nippon Bonsai Association and the American Embassy that March would attend the ceremony on behalf of the National Arboretum. Our good friend Dr. Frank Cullinan, the former chief of the USDA’s Bureau of Plant and Industry and then a trustee of the Friends of the National Arboretum, agreed to pick up Skip’s other expenses as the trip could not be funded by the agency.

I sent Mr. Edminster copies of the various letters about the ceremony and, all of a sudden, I was advised that the Agricultural Research Service was authorizing my travel. I immediately cabled our Embassy in Japan. Skip would still accompany me on the same financial arrangement as described above. We intended to return on the flight bringing the bonsai treasures to their new home. Without Skip’s help, it would have been a most traumatic experience for me because there were so many details to be worked out in Japan.

Announcing the Gift

Meanwhile, plans for announcing the gift went forward—the ceremony would take place at the fabulous Hotel New Otani in Tokyo on March 20, 1975. I drafted a letter for Secretary of Agriculture Earl Butz to Dr. Henry Kissinger, then head of the National Security Council, describing this remarkable gift in honor of our Bicentennial, and equating it to the gift of flowering cherries by the Japanese. The USDA also issued a glowing press release. The American Embassy in Tokyo did its share, advising the Secretary of State of the gift and describing the involvement by both the Japanese government and Imperial Household. Full press coverage was planned for the presentation by former Prime Minister Nobusuke Kishi, the acceptance by Ambassador James D. Hodgson and my brief remarks. The ceremony in Japan was to be a major diplomatic affair. I thought it might be appropriate to present the Japanese with a silver Bicentennial commission medal that Congress had authorized, and I persuaded the Commission to give me one to take to Japan.

Prince Takamatsu’s Trident Maple (Acer buergerianum) shares a tokonoma with a Mountain Range Stone, one of six viewing stones included in the Bicentennial Gift.

Bringing the Gift to the United States

Ceremony in Tokyo

By early 1975, preparations were completed to receive the bonsai collection at the Glenn Dale station, where the plants would be placed into quarantine. Two greenhouse sections had been emptied of other plants, and the benches had been sterilized and filled with clean gravel. Bob Drechsler transferred his office from the National Arboretum to Glenn Dale.

With everything in readiness, Skip and I took off for Japan, arriving on March 19, 1975. Mr. Koide and a delegation of NBA directors, representatives of the American Embassy, Miss Junko Arima as interpreter, as well as some Japanese reporters, met us when Pan Am Flight 1 arrived at Haneda Airport in the late afternoon. After expressions of congratulations, I was prepared for Mr. Koide’s first question: Was the Air Force going to transport the plants? When I replied that arrangements with the Air Force had fallen through, Mr. Koide exclaimed after a deep breath, “Saaaaa,” which in Japan is a note of serious despair. But I quickly said that we had arranged with Pan American Airlines to transport the plants and that this was probably a better idea. Much relieved, Mr. Koide said we must go immediately to the headquarters of the Nippon Bonsai Association to see the grooming of the plants for the grand presentation of the bonsai to the American people on the 20th. Of course with little sleep, we were not exactly prepared for this.

When Skip and I saw the size of some of the bonsai, we were aghast! In the Nippon Bonsai Association’s courtyard, on several long tables, there were the bonsai to be presented—including many very large ones. We were duly impressed with the activities of the magnificence of the bonsai, but uppermost in our minds was the question of how we were going to stretch $2,300 to pay the cost of shipping. And where would Pan Am find the space to accommodate such large bonsai safely? That night, neither of us had much sleep, wondering how we were going to resolve these problems. The next morning we immediately spoke to the Pan Am representative, Mr. Malcolm MacDonald, who said he could provide us with a cargo plane to handle the bonsai, but made clear that the cost would exceed our $2,300 budget.

Meanwhile, the day was spent getting ready for the festivities that were to take place in the afternoon of March 20. The guest list was most impressive. On the American side, Ambassador Hodgson led the delegation which included all upper-level Embassy staff, separate U.S. departmental agencies, the American Chamber of Commerce, the major newspapers and airline officials. In all, the number was about 100 persons. There were naturally far more Japanese. Among them were four former prime ministers, members of the Diet from both conservative and liberal parties, departmental heads, representatives of the Japan Foundation and, of course, a large delegation consisting of members of the Nippon Bonsai Association and the donors of the bonsai. Many from the foreign community were also included as permitted. It was said that this was one of the few occasions when leaders of the opposition parties of the Diet appeared on the same stage together.

Sylvester “Skip” March (left) and John Creech (right) with an unidentified man visit the Imperial Pine (Pinus densiflora) in the Imperial Household Collection.

The ceremony opened promptly on time and the band of the Imperial Household performed throughout the ceremony. The fifty bonsai and the six precious stones selected by the NBA were displayed around the perimeter of the main hall of the New Otani Hotel. The president of the NBA, Mr. Kishi, greeted the audience and Mr. Teisuka Takahashi, Vice President of the NBA, gave the opening remarks. He described how the bonsai had been selected from all four major islands of Japan, that they were “so noble as to reflect the real heart of the Japanese people” and that the bonsai would “serve as a Green Peace Mission to open a new road in the friendly cultural relations between the two nations.” Ambassador Hodgson officially accepted the bonsai on behalf of the people of the United States. He assured the Japanese people that we would do our best to preserve, protect and promote their beauty and an understanding of their artistry among our citizens in the coming years. He also likened the gift to that of the flowering cherries so many years before. I reiterated these viewpoints in my short speech, assuring the Japanese that these enduring symbols of our love of nature will be viewed by millions of Americans in the years to come.

Ambassador Hodgson then presented the Bicentennial Silver medal to former Prime Minister Kishi as a token of remembrance of the occasion. The guests then were invited to view the bonsai and partake of the refreshments. There were several toasts first with saké for the well-being of the plants in their future home at the U.S. National Arboretum, more informal speeches and then the guests mingled with the plants for the next several hours. “Fabulous” is the only way to describe the presentation, and I could not imagine the cost of the arrangements which were funded by the Japanese government.

Sylvester “Skip” March inspecting the filler used to soften the impact of the crates’ movements for the Bicentennial Gift bonsai shipment from Tokyo to Washington.

Members of the Nippon Bonsai Association waving goodbye to “their precious children” when the crated bonsai left their headquarters on March 31, 1975.

Dr. John Creech examining the crated Imperial Pine (Pinus densiflora) before it was loaded on a Pan Am 707 freighter for the flight to San Francisco.

Preparing the Gifts for Shipment

Immediately after the ceremony, the bonsai were returned to the NBA display yard in preparation for packing. This was an enormous task. The plants were spaced on display tables for preparation, and many members of the NBA were assigned to specific tasks for each plant. I got the impression that everyone wanted to share in the preparation of this important gift to the American people. First, each plant was repotted with a uniform soil mixture. Japanese plant quarantine officers meticulously examined the bonsai to assure that they would pass inspection by U.S. quarantine officials once they reached the United States. The soil surface of each pot was covered with cheesecloth, and then a layer of moist sphagnum moss, all of which was wrapped with bubble plastic sheeting and bound tightly with tape. The freshly repotted bonsai were then secured with cord to their pots.

Next, the crating began, the cost of which was borne by the Japanese government. Carpenters constructed individual crates on the spot to meet the size of each individual tree. These were sufficiently large to assure that no branches would touch the crate and yet would still fit through the door of a Pan Am 707 aircraft. An agent from the airline was there to check on this requirement. These cases were beautifully and meticulously crafted, consisting of a wooden base to which three slatted sides were attached. There was a false, thin plywood bottom stuffed underneath with shredded foam plastic and each plant rested on this, allowing for flexibility when the plane landed. The trees were placed in their individual cages and additionally secured with more lashings. After a final inspection by the quarantine people, the slatted fourth side and top sections were nailed in place. The suiseki stones were wrapped in heavy bubble plastic and crated similarly.

The crating operation required several days. During this time, Skip and I took care of the voluminous paperwork, including both Japanese and U.S. customs’ documents, export licenses, quarantine certificates and airline manifests. There was even a document of consignment from the Imperial Household that I had to sign. When I looked at one customs’ declaration the value of the 53 trees and six stones was listed as ¥131,100,000.

While the crating was going on, we learned which tree had been selected to be donated by the Imperial Household, and we were invited to the palace to see the choice. It was a 180-year-old red pine in a Chinese container that was of considerable historic importance. It stood about 5 feet tall and required four men to lift the pot.

By now we were in a state of real anxiety as to how I would explain to the Department of Agriculture that the $2,300 authorization had to be parlayed into a considerably larger sum. Each time that the PAA agent told me the price was going up, I telephoned the Department and advised them, for something like $9,000 and again around $13,000. But, when we saw the size of the Emperor’s bonsai and realized the size of the crate it would require, I threw all caution to the wind. I sent a letter to Mr. Edminister accepting full responsibility for the overrun. As it turned out the shipment would require an entire 707 freighter. I had just rented an aircraft for slightly over $19,000!

The bonsai arrive in Glenn Dale, Maryland on April 1, 1975, and begin their quarantine period before the official dedication in July 1976.

Pan American Airlines was especially generous, and their agent informed me that they were only billing for the cost to fly the aircraft to the U.S. Still, I had broken every rule in the bureaucratic book and did not know what to expect when I returned home to explain the overrun. Mentally I was prepared for the worst.

The Flight Home

With all trees crated, we were ready to fly home on March 31, 1975. The crated bonsai were loaded in seven trucks and lined up at the NBA headquarters. The NBA directors stood in a small group and, as the last truck rounded the corner, they became very quiet. I remember to this day their touching waves of goodbye to their precious children. This was a solemn moment for them as they were very anxious about the future of their magnificent bonsai.

It was late afternoon when Skip and I arrived at the Pan Am terminal at Haneda Airport. This was an exciting time for us as we watched the crates lifted onto pallets and then hoisted with a crane up to the loading dock of the freighter. It was late evening by the time all 59 crates were on board PAA flight 876 and the aircraft was ready to depart. Skip and I were listed as couriers on the manifest because the crew did not know what else to do with us. We climbed the stairs into the flight deck and were greeted by the crew who informed us that there were no accommodations on freighters except for them. They motioned for us to go back to the freight compartment of the aircraft. There all we could see was crate after crate lined up the entire length of the plane. We did find two jump seats against the bulkhead and a large microwave oven for heating the crew’s food. We strapped into the jump seats, the jets whined and off we headed for San Francisco.

There was, of course, no comfortable place to sleep and we were both dog-tired. We were given several blankets and found a place to lie down beside the crate containing the large wisteria bonsai. So we crawled under the blankets and eventually slept until we were awakened by a crew member as we approached the California coast just about dawn.

When the plane landed in San Francisco, we were met by Customs, Pan-American Airlines and USDA agents. The Agricultural inspector was especially helpful and assisted us through quarantine quickly. The Customs agent, however, had a problem. It seemed that USDA research materials were entered duty-free but nobody had envisioned that it would include a shipment of such high monetary value. Thankfully, he signed the release and said that the folks at our final Baltimore destination could solve the problem. We also insisted on clearance then so as to avoid delays in Baltimore. So on the form was written “State Department Letter to Follow,” but I do not think one ever came.

Because Pan-American Airlines could not fly across the country, their agent in Tokyo had arranged for two United Airlines DC-8 cargo aircraft to transport the trees to Baltimore and they were standing by. The trees were transshipped. Skip took one plane and I the other, and off we went on the last leg of the journey. Our only concern was that the planes made a stop in Chicago to unload other freight, and we feared that if the crates were unloaded in the freezing weather the plants would be harmed. The Japanese maples were already coming into leaf. But the crews worked it out so that while the plane sat on the ground the trees were kept inside. We departed Chicago quickly and arrived at Baltimore International Airport on the evening of March 31. The plants were unloaded and put into a hanger until our trucks from the Glenn Dale station could take them to their new home. Skip and I were so tired we took a room at the nearby motel and slept until early the next morning.

The greenhouses at Glenn Dale were ready. Bob Drechsler and others from Glenn Dale and the National Arboretum were on hand when the trucks were unloaded and the crates placed on the ground outside the greenhouses. The trees were gently lifted out of the crates and taken into their new quarters. They were now Bob Drechsler’s charges and he hovered over them like a hen over new-born chicks. The Japanese bonsai gift to the American people had arrived!

Making the Best of Quarantine

With the bonsai collection safely at Glenn Dale and Drechsler as the curator, he and the Glenn Dale staff proceeded to provide improved quarters for the trees. New insect screening was installed on the greenhouse windows and vents, attractive wooden slats were placed on the benches to avoid scratching the ceramic pots, and the entire greenhouse was thoroughly cleaned.

A few days after the collection arrived, John Naka came from California and walked through the collection giving suggestions to Bob. John pointed out that several of the “jins” (dead branches retained on the trees) needed treatment with lime-sulfur to intensify their whiteness. Bob obtained the lime-sulfur and painted the “jins” which promptly turned them yellow-orange. Being new at caring for bonsai, Bob was horrified at the color. But after a few days, the “jins” turned snowy white as they should be. Relief!

The presence of this splendid present from the Japanese people had a remarkable impact on the Department of Agriculture. Mr. Edminster was able to find funding for the cost of the transportation, and I did not “fall from grace” or go into debt personally. Probably the reason was that the collection was receiving considerable praise in the Washington press. The visits to Glenn Dale by Ambassador Fumihiko Togo and the entire senior staff of the Japanese Embassy doubtlessly helped as well....

A small delegation of Nippon Bonsai Association directors flew over from Japan in May to determine the health of the collection, and they were totally pleased with the way Bob was handling his new assignment. Everyone’s main concern was whether the bonsai would tolerate quarantine greenhouse conditions during the summer. The extremely fine screening that was required for quarantine purposes cut down on air movement and resulted in higher temperatures. We had installed cooling fans in the greenhouse as a temporary measure, but that was not adequate. Fortunately, there was an unused screenhouse structure on the grounds that had been used to house quarantined citrus plant introductions. It made a perfect summer house. It had a glass-paned roof and screened sides. Furthermore, it was enclosed with high chain-link fencing and locked gates that gave added security for the bonsai. The structure was completely refurbished, and by June the bonsai were in their new quarters where they remained until autumn. This was especially reassuring to the NBA directors, and they returned home prepared to make glowing reports to their members.

Dr. Creech unwraps a bonsai in quarantine where it would stay for more than a year before moving to the Arboretum to begin its public life in 1976.

Meanwhile, the quarantine inspectors made periodic visits to Glenn Dale and gave the trees a thorough going over. Happily for us, the inspectors were perfectly satisfied as to the health of all the bonsai and could find no insect or disease problems. We had to be somewhat selective in accommodating visitors because Glenn Dale was still a quarantine station, which gave us a good excuse to limit visitation. However, many bonsai club members requested to see the collection and, of course, we accommodated them as best we could.

We considered having John Naka come from California to consult on a regular basis. Because of financial limitations, however, the care of the collection was left strictly in the hands of Bob and his new volunteer assistants, Dorothy Warren, Ruth Lamanna and Janet Lanman. These faithful women were Bob’s constant helpers throughout his tenure and soon refer to themselves as his “grandmothers.”

The health of the collection was good except for the cryptomeria forest that had been in questionable health when it was chosen. Our Japanese friends admitted that perhaps it should not have been included. Although a couple of the small trees in the forest had died, Bob managed to give his special attention to the rest and brought them to a healthy condition by the end of the year. The Japanese especially praised this effort because Mr. Eisaku Satō, a former Prime Minister and Counselor of the NBA, had donated that particular forest.

Creating the Japanese Bonsai Pavilion

In June 1975, we received bid invitations for the design of the viewing pavilion from 48 architectural firms. Because of the special nature of the facility, an understanding of Japanese display concepts and garden design was of prime importance. The nationally known architectural firm of Sasaki Associates of Watertown, Massachusetts, was selected to provide the design components and to supervise construction. Mr. Hideo Sasaki had a fine reputation and served on the Fine Arts Commission for the nation’s capital. His associate, Masao (Mas) Kinoshita, was an authority on Japanese design concepts.

I had already selected the most logical site for the garden, just off the broad central plaza that faced the administration building. This location offered two advantages. It was readily accessible by foot from the administration building and offered a degree of security. It was also close to parking.

After several concept meetings with the Sasaki architects, we finally agreed on the present design. It included an entrance walk through a forest of cryptomeria trees that would be under-planted with Japanese woodland plants....

The entire facility would be walled and open to the sky above. An outside perimeter walk would circle the wall and lead to the handsome double metal gates at the entrance of the garden....

During the late summer of 1975, the Arboretum’s maintenance supervisor, Bill Scarborough, undertook the rough grading and removal of excess shrubs and trees. He had to operate a small front-end loader delicately in very tight spaces to avoid damage to the perimeter walls that were being simultaneously constructed. With the grading finished, the planting of the entrance trees could begin. Among the specimens that could now be planted were the 23 cryptomerias for the outside perimeter walk. Locating mature trees would be a considerable expense. Fortunately, Scarborough had previously worked for the well-known Greenbrier Farms Nursery and approached them with our need. We paid a visit to the nursery and were shown a field of abandoned cryptomeria trees, some of which were 20 or more feet tall. We were offered these for only the cost of transportation from middle Virginia.

A U.S. Department of Agriculture inspector examining a Bicentennial Gift bonsai with a magnifying loupe, looking for insects or disease problems.

It was the old transportation story all over again because one early morning in October several large trucks loaded with the balled cryptomerias appeared at the Arboretum. I had not even contracted for them and the bill was several thousand dollars. But again our business office at Beltsville, Maryland, managed to work out details and my reputation was again saved. With his skilled use of the loader, Scarborough smoothly placed these large trees in perfect alignment to make the pathway into the pavilion....

There was a need for a row of tall crapemyrtle trees set on mounds to permit their tops to appear above the wall. There was only one place to acquire them and that was from Donald Egolf, the Arbor-etum’s famous crapemyrtle breeder. One had to know Don to realize that getting him to release some of his precious “children” for our cause would not be easy. After all, we had absconded with his top technician, Bob Drechsler. But when I approached him, Don generously offered some of the best hybrid seedlings in his nursery. Today, these are a spectacular aspect of the entrance garden. What makes this more interesting is the fact that one parent of these hybrids is the rare Lagerstroemia fauriei that I had introduced from Japan back in 1956. So I suppose Don felt that he owed me something.

Now came the matter of stones befitting a Japanese garden. Mas Kinoshita was to personally select these for their individual character and, as many know, this is something only a trained Japanese eye can appreciate. So one cold snowy January day he and I drove to a stone quarry near Valley Forge, Pennsylvania, arriving late in the day to pick out the stones. As cold as it was, Mas moved easily among the candidate stones, selecting them for quality and character, and assuring that they had the proper faces and other aspects to meet his rigid standards. In Japan he could have gone to a “stone” nursery where choice stones are for sale, but his selections were both handsome and unblemished. How appropriate it was to have stones from Valley Forge for the Bicentennial garden. Upon delivery, Mas marked each stone’s front and reserved it for its chosen location. With the help of Bill Scarborough, they each were placed at the correct depth in the standard Japanese manner using a pole tripod and ropes.

In summer, the trees were moved outside within the quarantine area. The Imperial Pine is the largest in this image and the Yamaki Pine is to its right.

Development of a Logo

One item I considered important was a logo for the collection—that is, a kind of family crest (mon) such as I had so often seen in Japan. This would be a visual identity of the National Bonsai Collection. In February, I requested assistance from the USDA Visual Services, and Beverly Hoge of the USDA Office of Communication was assigned to locate a graphic arts specialist to effect the design. I suggested that the crest be designed within a circle similar to those depicted in the Japanese book of crests, and I loaned my copy to Ms. Hoge for guidance.

A local graphics designer, Ann Masters, accepted the contract to develop the concept that ultimately became the symbol of the entire bonsai and penjing complex. This design was later adopted as the symbol of the support organization, the National Bonsai Foundation. Ms. Masters had traveled in Japan and had freelanced for several prominent magazines, including Time/Life. The concept was to be drawn from the collection itself, and she provided several sketches using various stylized versions.

Ms. Masters visited the collection at Glenn Dale and chose the 250-year-old Shimpaku (Juniperus chinensis, var. sargentii). Her initial sketches consisted of a Juniper with the twisted trunk and masses of foliage to depict the luxurious growth of the collection. The final design featured the Juniper within a double circle, reflecting the sturdiness of the bonsai tree and its massive foliage. Because a branch broke the bands of the circle, the design also symbolized the continued vigor of the trees in their new home.

The National Bonsai & Penjing Museum’s logo is emblazoned on one of its gates, with the U.S. National Arbor-etum’s Capitol Columns seen in the distance.

The Sargent Juniper (Juniperus chinensis var. sargentii), whose twisted trunk and pyramid-shaped foliage inspired the logo design, shown with its donor, Mr. Kenichi Oguchi.

Tsunekazu Nakajima, a Nippon Bonsai Association member, makes final adjustments to the logo tree in preparation for the dedication ceremony in 1976.

A sequence of sketches demonstrates the development of the museum’s logo created by Ann Masters along the lines of a Japanese family crest or mon.

The NBA Directors Visit Their Bonsai

In October 1975, a large delegation of NBA directors traveled to Washington to see how the bonsai were doing. As this was the first visit to the United States for most of them, we planned a gala event. First and foremost was a visit to Glenn Dale to see the collection and hold discussions with Bob Drechsler and his volunteer assistants, Ruth Lamanna and Janet Lanman, both longtime bonsai growers and members of the Potomac Bonsai Association. Mas Kinoshita was also present along with Skip March and me so that we could discuss the plans for the viewing pavilion at the Arboretum. It was important that Kinoshita be present because he could discuss the plan in Japanese since these elderly bonsai masters spoke little English and depended on the young interpreter for other conversations.

The NBA directors were delighted with the health of the bonsai. They made a few observations on training and maintenance to Bob, and said some of the plants never looked better. Then they were taken to the deep pit greenhouse where the plants could over-winter. This was an unheated pit greenhouse dug in English style several feet below the ground surface and completely frost proof. This especially pleased the visitors. The next few days we escorted them to sites around Washington, including a visit to Mount Vernon, a private visit to the White House, and a trip to Longwood Gardens in Kennett Square, Pennsylvania.

The last of their four-day visit ended up at the Arboretum where they inspected the pavilion site that was then only a graded area. But they saw all the plans and held further discussions, particularly with Mas Kinoshita, and were greatly pleased when we explained that everything was aimed at a July 9, 1976 dedication. As they were leaving for the airport, one of the directors stated that they would like to present 20 additional bonsai to complete the collection. While I expressed appreciation for the offer, in my mind I had enough on my plate for the present and let the matter rest until I heard further from Japan. But just to set the opportunity in motion, I wrote to our plant quarantine colleague, Ivan Rainwater, about the offer and received a letter of authorization for future importation. This did not actually occur until 1998, so the Japanese do have long memories.

The NBA directors brought with them a 16 mm film that they called “How the Bonsai Came to America,” which captured the entire sequence of events in Japan earlier in the year. This documentary was shown at the Arboretum many times that autumn, including to Ambassador and Madame Togo on the occasion of their visit to the Arboretum and Glenn Dale. We had become fast friends with the Japanese Embassy staff and on several occasions Skip March and I were invited to receptions at the Embassy. Skip was often asked for advice on plantings at the new embassy residence. In addition to the film, the NBA produced a beautiful folio size documentary book in English on the presentation ceremony with full-page photographs of each of the bonsai and stones in the collection and the text of each of the speeches that were made. These books have become an historic record of the Japanese side of the gift and were presented to various American officials and agencies concerned with the occasion.