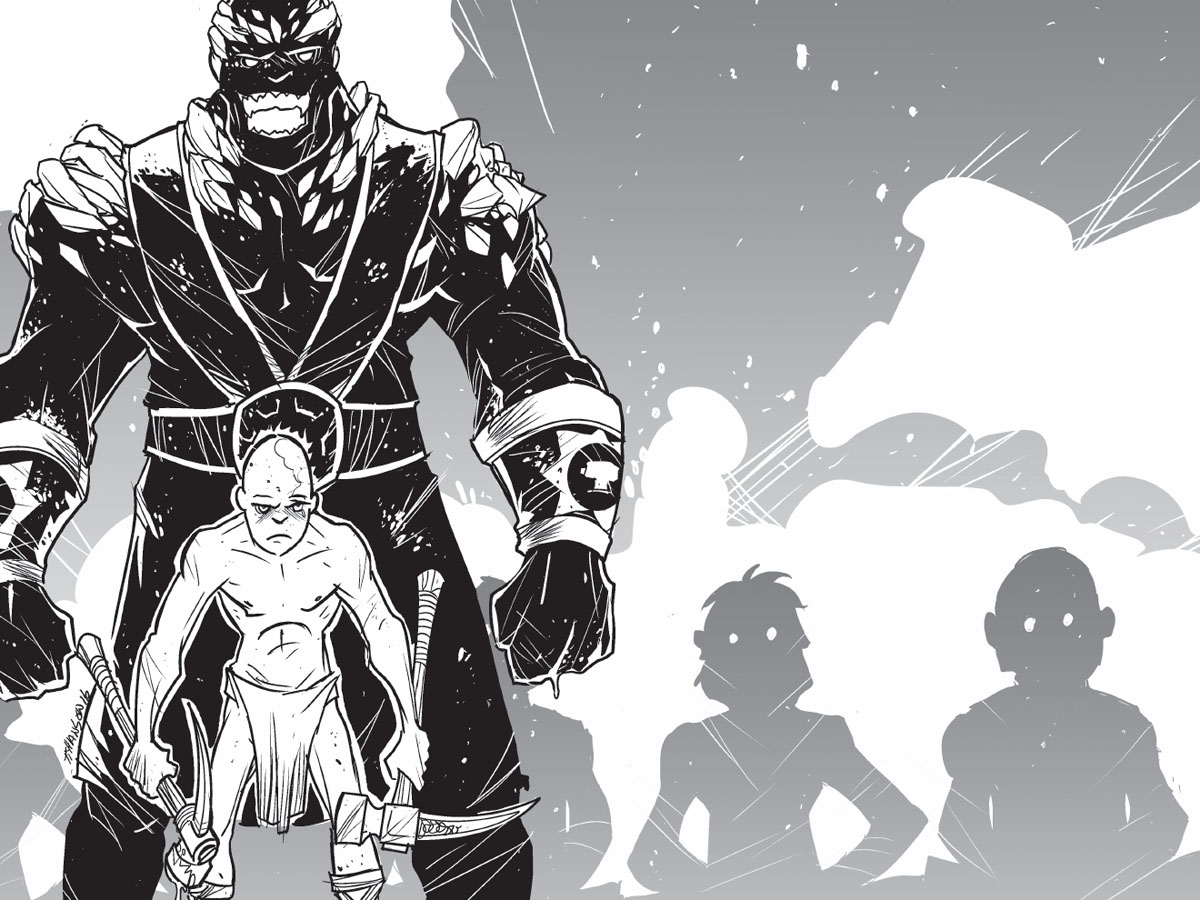

“Maveith!” commanded his father. “Rise and show your mettle.” General Eglak Oglakanu was tall even by behemoth standards, standing nine feet four inches into the sky. His chest and shoulders were thick with callused fungus; his skin was slate blue with champagne colored godmarks splattering and splotching his entire body. General Eglak was girded by a five-inch-wide leather belt studded in gold. A white breechcloth with gold trim hung from the belt to his knees. His shins and knees were protected by ornate gold greaves with intricate tribal designs; his forearms covered by gold bracers of the same make. Across his chest criss-crossed two brown leather straps. At the intersection was a golden medallion of Yauuh—a half-round sun the center of which was carved out into the shape of a smith’s anvil. A clutch of dwarves and other behemoths stood next to General Eglak clad in various white and gold dress and armor. Fresh cleric graduates from the abbey sat in a circle twenty-five feet in diameter. A drákōnblood youth clad in shiny golden chainmail fresh from the smith stood in the center, a blood-splattered shield and war pick in his grasp. On the ground lay an older man with white, wispy hair and beard. Two dwarf soldiers clad in white and gold armor with the sun and anvil symbol emblazoned onto the chest stepped through the circle and carried the old man off.

“Nicely done, faithful servant of Yauuh,” said General Oglakanu. “Together boys, we will bring the light of Yauuh to all who suffer and show them the path of righteousness. Those who refuse and embrace wickedness will be crushed beneath his holy hammer.” The General picked up his war hammer by the butt end and slammed it into the ground. His hammer was a worthy instrument of holiness—the very embodiment of Yauuh. In place of a traditional hammer head was a spiked sun with an anvil in the middle attached to a long handle, the same symbol on his chest. “Now my son will show you all the power and might of Yauuh.

Maveith stood up from the outer ring of the circle and walked to the center. The drákōnblood boy took Maveith’s place around the circle and sat down. The other boys in the circle were seventeen and eighteen, nearly grown men, some with beards and thick chests. Maveith was a boy of ten, smooth skinned and innocent. He stood in the circle looking down.

“Bring my son a worthy opponent,” ordered General Oglakanu. Two more dwarf soldiers escorted a human male to the circle. He was in his early twenties, clad in leather armor with a black cloak. The dwarves handed him a long sword. It was unsharpened but only General Oglakanu, the escorts, and the man knew it. The human laughed and shook his head.

“You have been found guilty of crimes against guardian and man,” declared General Oglakanu. Your sentence lies in the hands of Yauuh, the one true guardian of light and righteousness.”

“You want me to fight this boy?” the human questioned. “I’m not going to kill a child.”

“Then my boy will have an easy day doling out guardian’s punishment.”

“If I win?” the human asked.

“Yauuh will not allow it,” the General laughed. “But if you do, it will mean the boy was meant to be with Yauuh earlier than we expected. And you,” he paused, “will go free.”

Maveith approached the man wearing only a loincloth and sandals. He carried two small war picks each engraved with the symbol of Yauuh. Maveith twirled the war picks as he circled the man.

“He is unholy, son,” called General Oglakanu. “Strike him down!” The graduates in the circle hooted and clapped, cheering on Maveith.

Maveith stepped in and jabbed at the human who side-stepped and deflected the shot easily. He tested again, watching the human move. Maveith shot a third time and the human reacted with a parry and an overhead strike. A hit would have cleaved Maveith in two, but he was nimble. Most humans had little or no interaction with behemoths, giving Maveith an edge. Even as children behemoths were very strong and quick. Maveith was known throughout the cleric world as a prodigy of war. By age ten, his strength, stamina, and agility rivaled most trained soldiers. He learned war at a pace double or more than any other soldier, including his own father.

As the human made his strike, Maveith dodged and punched the side of the the man’s rib cage with the spike end of his war pick. He didn’t delve deep enough to puncture a lung, but the man was bleeding profusely. The human, now angry, came after Maveith in a flurry of blows, swinging the long sword hard and fast. Rather than take the brunt full on, Maveith dodged and deflected the man’s energy aside over and over again until the man exhausted himself. Maveith moved in like a viper and ended the human with a blow to the temple using the hammer side of his war pick.

“Another evildoer smitten down by the power of Yauuh!” claimed General Oglakanu. He walked into the circle and held up his son’s arm. “This boy has been touched by Yauuh himself. The shaman has read his godmarks,” General Oglakanu pointed to Maveith. “Maveith is anointed by Yauuh and is destined to become the greatest cleric of Yauuh this world has seen for one thousand years!” Maveith stood shyly. He handed his bloody war picks to a dwarf cleric as his enemy was carried off the field. “Good job, faithful servant of Yauuh,” his father said. “You are supposed to attend the abbey and begin your formal cleric training, but you clearly know everything these older recruits learned at the abbey,” he said as he pointed to the new graduates on the ground. “The shaman says you must stay with us and be trained alongside these new soldiers.” The new cadets eyed one another cautiously.

That evening Maveith celebrated with the men during a feast in a tent serving as the great hall. He didn’t sit at the table with his father, but sat amongst the newly graduated. The young men talked and laughed, filling their faces with roasted lamb, pan fried Brussel sprouts and potatoes, and either ignoring the younger Oglakanu or mocking his destiny. Maveith sat quietly, ate, and listened.

They were friends, the young men. They attended the abbey together, learned together, ate together. They were a team. Maveith was much younger and not part of their group. Bored of listening to talk, Maveith left the table and went outside. He wandered around in the night. The grassland glistened in the light of the full moon. Maveith wandered to the stockade and peered through the wood-slot fence at the people sitting inside. They were dirty and hungry, all of them, corralled in a makeshift cell until their trial by combat. Some were obviously poor, wearing ragged clothing with holes and tears with over worn sandals or barefoot. Others were soldiers from outlying cities with remnants of their military uniforms and rankings still intact.

“Hi, Butcher,” mocked a blonde-haired girl about his age. She leaned against the fence of the stockade, peering out through the gaps between the wooden slats.

“I’m not a butcher. I’m a soldier.”

“You killed easily enough today, Butcher,” she said.

“That man got what he deserved,” Maveith said, absently.

“And how do you know that?” she asked.

“He went through a trial and was found guilty.”

“A trial. Ha!” she snorted. “You are an idiot.” She snarled at him, then turned.

“He committed a crime against Yauuh. His sentence was just.”

“Just!” she yelled, turning back to Maveith. “Just? What do you know about justice?”

“I know Yauuh gave him a chance for freedom. All he had to do was defeat me in battle. If his cause was just, he would have beat me and won his freedom,” announced Maveith confidently. He smiled, proud of himself.

“Freedom?” she screamed as she launched herself into the fence. “Then why did the soldiers break his ribs before his battle? Huh? Your precious Yauuh need a little help dispensing justice?”

“You are a stupid liar.” Maveith shot. He turned and walked away.

Maveith wandered the camp muttering to himself. That girl is stupid. She just wants to get back at me for dispensing Yauuh’s justice. He roamed the camp for another hour, the conversation rolling through his head. Finally, Maveith decided to prove her wrong. He went to the outskirts of camp where a pile of unholy bodies lay stacked. The man he defeated was on top. Maveith climbed up the pile of bloody and broken bodies and pulled the man off. He laid him on his back, took out his knife and cut the man’s tunic away exposing his torso. Both sides of his ribs were bruised. Maveith pushed and felt the ribs move. His ribs are broken, both sides, he thought.

Maveith went back to the stockade and stood in front of the fence, looking between the slats for the girl. He spied her sitting in the far corner huddled up against the cold of the night. Maveith moved along the freestanding stockade fence closer to where she sat.

“Hey. Girl!” he called.

“Go away, Butcher,” she said not looking at him. “You can serve me my justice tomorrow in the battle ring. I’ll be sure to break my arm first so I can’t hurt you.”

“What did he do?” Maveith asked.

“What?” She still didn’t look at him.

“What did he do? The man I killed today.” She stood up, turned to him and cocked her head.

“What do you think he did, Butcher?” she asked.

“I don’t know. He sinned against Yauuh is all I know.”

“You know nothing, Butcher,” she laughed. “My father, the one you slaughtered today, beat one of your cleric captains in a game of three-card pony. Took him for thirty gold.” She laughed. “The captain paid him and left. In an hour, he returned with five other soldiers. Claimed my father cheated the church out of taxes because we pretended to be poor so we didn’t have to pay our monthly love offering to the church. He searched my dad and pulled out the thirty gold father just won. He kept the gold, of course, and arrested my father and me. Tried us as heretics.” She stopped and looked at Maveith, studying his face.

Maveith felt sick. He killed a man for being poor, and at the time felt proud of the ease at which he doled out Yauuh’s justice. He turned from the girl and ran to his tent, embarrassed and ashamed. The next morning, the cadets ate in the early morning, trained in the afternoon, prayed and worshipped during early evening, then sat down together for dinner. Maveith wasn’t hungry, still feeling sick from the night before. He stood up from the table and approached his father.

“General, sir. May I have your leave to depart dinner early to go to my tent for calisthenics and worship?” General Oglakanu studied Maveith’s face and nodded.

“I always say a strong faith requires a strong body,” he said to Maveith, then poked a dwarf captain sitting next to him. “Hear that, Rotbek? Maveith is leaving to train and pray. What’s your son doing?” He pointed at a dwarf cadet drinking a pint and laughing. The general roared with laughter then flicked his hand at Maveith who turned and left.

Maveith left and headed straight for his tent. Maveith trained and ate with the new cadets, but he still slept in his family tent with his father and mother, who insisted that too much time with the privates would corrupt her young son’s soul and spoil his piety. Maveith went to his father’s war table and snagged a set of keys. He left the tent and snuck to the stockade. It was guarded by two dwarves who were sitting on the ground playing a pirate card game.

“Ho, Maveith!” said one of the dwarves barely looking up at him.

“I’m to deliver the blonde girl to the great tent,” he said calmly, though he could hear his heart pounding in his skull. He held up his father’s keys.

“Okay. You want help getting her?” the other dwarf said with a chuckle. Maveith rolled his eyes.

“I can handle it, thanks,” he snarked. Maveith unlocked the door and went inside. It smelled bad even to Maveith and he trained all day in the hot sun with dwarf soldiers. In the corner sat three buckets which the prisoners used as a latrine. He moved through the throng of heretics and evildoers, and wondered about their trials and guilt. The girl was lying in a ball on the ground, her hair limp in the dirt. He kneeled next to her, tapping her shoulder. She turned, saw him, and jumped and screamed.

“You okay, Maveith?” shouted a guard.

“I’m fine,” he snapped, then whispered to the girl. “I’m sorry I killed your father. I’m here to rescue you.”

“Rescue?” she said loudly.

“Shhh. Do you want to get us killed?” he said sternly.

“If it means your death, Butcher, then yes. I’m going to die in the next few days anyway,” she stated simply.

“I’m going to save you.”

“I saw how you saved my father. No thanks,” she snapped as she turned and sat back down on the ground.

“I have keys,” he said waving the keys in front of her face. “I can release you.” She looked at him out of the corner of her eye.

“Why?” she asked. Maveith leaned in close to her.

“I found your … your dad’s body. His ribs were broken.”

“I already knew that,” she said. “Go away.”

Maveith stood up frustrated. Angry. Hurt. Confused. He was everything all at once and the emotions attacked his stomach again, making him want to scream and wretch at the same time. Maveith could not think a single, complete thought. So he acted instead. Maveith left her in the dirt and walked to the gate. He pushed past the dwarves still playing their game and grabbed a cotton strap from a barrel and a leather shackle from the wall.

“We can help …” said a dwarf laughing.

“Got it,” Maveith interrupted. Stupid girl. If she won’t let me help her, then I’ll have to make her help me help her. It sounded stupid to him, too, but he couldn’t think things through. Maveith found the girl again and jumped on top of her back, pinning her to the ground. He placed the leather shackles around her wrists as she screamed. Despite her thrashings, he managed to roll her over and sit her up. Maveith pulled the cloth strap from his belt and wrapped it around her mouth and tied it tightly behind her head. The prisoners moved back, giving him room. He got behind her and tugged on her shackled hands, forcing her to her knees, then standing. “Let’s go!” Maveith pushed her through the makeshift prison and out the door.

“Have fun, Maveith,” said one dwarf.

“Whatcha gonna do with her, Mave? Play Kings and Thrones?” mocked the other. They laughed.

“You could play 3-card pony,” the first said. “Here. Take our deck.”

Maveith continued ignoring their taunts. He kept his hand on her shackles, directing her body where he wished. He walked toward the great tent at first, but as soon as the darkness concealed him from the stockade, he turned north toward the forest. The more they walked the faster he pushed her, increasing their pace from a fast walk to a slow jog.

They jogged for five miles until she collapsed on the ground. Maveith reached down and untied her mouth. She was panting; he was not.

“Water,” she gasped.

“I don’t have any with me,” he said.

“You kidnap a prisoner from the Yauuh war priests and don’t bring water? Not much of a savior are you?”

“Well, uh I didn’t think…” Maveith stuttered.

“Have you ever thought?” she asked, seriously. “For yourself, I mean?” Maveith pointed to the edge of the grassland where the forest began.

“There is a river just beyond the forest. We can get water there. It’s only a half mile more or so,” he said proudly.

“Thanks, Butcher. I’m sure no one will think to look for us along a river.”

“I’m trying to help you.”

“Your god helped us plenty when you arrested my father for winning in a game against your cleric,” she shouted.

“I didn’t do that,” he pleaded.

“No, you smashed his skull in.” Her voice was quiet; her eyes hurt.

“I’m sorry. I didn’t know.”

“That seems to be a theme with you, Butcher,” she mocked.

“I’m trying to make it right, you know,” he shouted. “I’m trying to free you.”

“And where will I go?” she asked. “You are the General’s son, right?” Maveith shook his head. “Daddy will be mad at you but he’ll forgive. Me? He will hunt me down, but this time instead of allowing me to die quickly in a battle, I’ll be tortured for somehow corrupting you. It’ll be worse for me now.”

“I didn’t …”

“If you tell me one more time that you didn’t think, Butcher, I am going to kick you in the grapes the next chance I get.” She turned her back to him. “Now, take these off my wrists.” Maveith unbuckled the leather shackles letting them fall to the ground. She stared at him inquisitively. “Why’d you do that?”

“What?”

“Drop the shackles.”

“We don’t need them anymore,” he said hesitantly.

“Leather. Brass buckles. We can trade them for something we do need,” she pointed out. “I bet you didn’t think of that, did you?” He just looked at her. “Don’t answer that. It’ll make me want to kick you in the face.” Maveith stared at the shackles on the ground. She leaned down and picked them up, tucking one end of them through her cord belt. “Besides, if we leave them here, Butcher, then when they come looking for you, they will know we were here. Might as well make a sign that says, “They went thataway!”

“Hmm,” grunted Maveith.

“If you are going to save people, you need to start thinking like a starving street kid not a privileged general’s son.” She turned and headed off into the forest. “Come on, let’s find that river, Butcher,” she said leaving him behind.

“Okay,” he said, following her.

They traipsed through the forest, on the downward slope toward the river basin. The ground leveled out and they found themselves at the bank of a wide river.

“We need to find shelter,” said the blonde girl.

“What’s your name?” asked Maveith. It dawned on him that he never bothered to ask.

“Gladys,” she answered quickly. She turned and examined the river.

“Aren’t you going to ask mine,” Maveith asked.

“I already know your name, Butcher,” she said, without looking at him. “Besides, right now we need to think about surviving another twenty-four hours not playing Old Crone.”

They moved north up the river bank against the river’s current being careful to walk on dry land so as not to leave a footprint. The girl kept a quick pace for a human, although it felt like a stroll to Maveith. They followed the river bank as far as they could until they reached a rock bluff.

“Climb up and over, swim out and around. That’s our choices, Butcher?” said the girl.

They scaled the rock bluff and found a clearing on the top. From there they could see the river for quite a distance. Maveith spied a small island in the middle of the river about five hundred yards north.

“We could hide there, Gladys,” he said, pointing to the little island.

“Island?” she said. “More like a jail cell in the middle of the river. It’s so small; what, one hundred yards wide at the most? There won’t be any animals on it to hunt. Can’t build shelter or it might be seen.”

“All reasons why they won’t look for us there, right?” he said. “We’d be stupid to hide there. They will pass it by, thinking we are too smart for that.” The girl thought for a while, pondering the plan.

“Can you swim?” she asked.

“Better than you, I bet,” he said smiling.

They scaled down the other side of the bluff and made their way north. They reached the bank near the island, jumped into the water and swam. Maveith pushed hard to take the lead, reaching the bank of the island first. He climbed out of the water and laid on the beach. The island was small and round, no more than one hundred yards wide. The bank was rocky with stones the size of walnuts and oranges. It would be unbearably painful to walk on barefoot unless one’s soles were used to it. Trees grew right up to the river bank. Most were oak and maple with a few pines peppered in. Small shrubbery grew interspersed with grasses and underbrush. They headed to the center of the island and laid down in the undergrowth. From there, they could barely see snippets of the river through the brush.

“We won’t be able to get up and move around,” she said. There’s not enough cover. They might see us.” The sun was rising in the east, lighting the sky.

“So, we’ll lay here, Gladys, until it’s safe,” said Maveith. “Is your name really Gladys?” he asked.

“Boys are idiots,” she announced as she found a huckleberry patch. The plant grew wild and thick, with red branches and green leaves that were nearly as tall as Maveith. The berries were dark red and round, similar to a blueberry but tart. She made her way to the middle of the patch, careful not to smash the plants. “Throw me a blade,” she commanded. Maveith drew his boot knife and held it in his hand. “Afraid I’m going to try to murder you?” she sighed. “You’re the butcher, not me.” Maveith flipped the knife handle-up and tossed it into the air. She caught it, bent down, and cut some huckleberry plants away at the ground, creating a comfy hidey-hole in the middle. She tossed the cut branches on top of the patch to create extra cover. “We can stay in here,” she said pointing at the little cave-like space. “It will hide us from them well enough.”

“General will be looking for us by now,” said Maveith.

“You call your dad ‘The General’?” she questioned. “That’s kinda weird.”

“Not ‘The General’; just ‘General’. And, yeah, I do.” The girl looked at him with disgust. “That’s what everyone calls him, even my mother.”

“Seriously? Your mom calls him ‘General’?” Maveith had never questioned his father before. It wasn’t allowed, but this girl made him see his entire life from a different perspective and he didn’t like it much.

“He’s the most powerful war priest in the entire country,” Maveith corrected. “He speaks for the will of Yauuh. He deserves respect.”

“But he’s your dad. You can’t call him ‘father’”? You have to call him ‘General’? Capital G, ‘General’. That’s pretty controlling of him,” she challenged.

“It’s not controlling!” Maveith shouted. “It’s training and respect!”

“Okay. Whatever,” she murmured with a shrug. “Let’s get some food.”

The two gathered huckleberries from smaller patches around, but not from their patch. Maveith gathered from the patch in the east; the girl picked from the west. Maveith was shirtless with only a belt and white and gold breechcloth, along with gold bracers and greaves, like his father. Maveith gathered his palms full, came back and sat down in front of their huckleberry patch hidey-hole. The girl held the hem of her tunic and made a little bowl. She filled it with twice the berries he collected. They crawled into their huckleberry cave.

“Be careful not to smash last night’s dinner and this morning’s breakfast and probably lunch,” the girl said. She crawled on her knees and one hand, leaving the other hand holding her tunic bowl. Maveith crawled on his knees and forearms like a soldier scrambling through the mud. They got inside and laid down on their sides, facing each other. The girl let her hem go and the berries rolled out between them. He opened his hands, which ran rich with huckleberry juice. She picked a huckleberry leaf and used it as a spoon from his hand-bowl.

“A little messy,” she said glaring at him. “But good. They’re tart, but I like them.”

“Sorry about that,” he said as Maveith dipped his lips to his hands and slurped up the juice.

“And I’m the poor gutter rat,” she laughed then put her lips into his palms and slurped, too. They emptied his huckleberries, leaving his palms stained blood red with streaks of juice running between his fingers and down his arms. She lightly flicked the rest of the berries to a clear spot above their heads. “We’ll eat the rest later. We may be here a long time.”

They laid in their huckleberry cave, facing one another and whispering about their lives. Maveith told her about his life as an Oglakanu. The girl told him of her mother’s death from the Pestilence and how her father spent everything they had taking her to every shaman, wyzard, sage, healer, and apothecary in the world looking for a cure. In the end she died the same as the rest and the family was destitute, resorting to gambling and odd jobs to have enough food to eat.

“That thirty gold we won would have been enough to feed us and help us get clothes so we could look well enough to get jobs,” she said tearfully. “We…” she paused. “… could have … made it,” she whispered staring into the forest.

“What …” he asked.

“Shhh.” She careened her neck, closed her eyes and listened. Maveith watched her then did the same. Murmurers, light as a squirrel chatter, drifted along the breeze, barely louder than the sounds of the rushing river. Twinkles of golden sunlight flickered off well polished armor. The clerics tracked them or lucked into them. Neither Gladys nor Maveith could tell which. The girl spied his white breechcloth and her eyes widened. They will see his white and gold cloth and find us for sure, she thought. She put her finger to her lips then pointed at his breechcloth. She then pointed two fingers back at her eyes. Maveith nodded slightly then shrugged his shoulders.

“I’m sorry,” the girl mouthed at him. She quietly leaned up on one elbow and grabbed his belt. She slid the buckle out, pulled the leather and unhooked the belt. The girl closed her eyes tightly, then grabbed his loincloth and took it off his body. His face turned red, his eyes wide as a doe, but she didn’t know. She wadded the loincloth up and shoved the ball of cloth into his body covering his front side nakedness, but leaving his rear exposed. His slate skin and her brown tunic blended well into the flora of their surroundings. They hid the white breechcloth between them and laid still.

The murmurs of the soldiers turned into babbling which turned into discernible voices. The soldiers stomped through the island forest like a parade of mammoths. Two mouth-breathing dwarves walked up the hill near the huckleberry patches.

“Argh!” he shouted. “I can’t breathe. I’m stobbed up.”

“Quit yer complaining and search for the General’s son.”

“I am!” The dwarf stopped at a bush and picked some huckleberries, tossing them into his mouth. He looked around, listening to the sounds of the forest.

“Whatcha doing?” the other said as he walked up.

“Just listening,” he said as he chomped the berries. “They couldn’t have made it this far. Probably are back at camp already.”

“Agreed. Let’s move on.” The dwarves walked up to the kids’ patch, but it was thick. The dwarf picked more huckleberries and ate until finally they walked on. Maveith and the girl laid on the ground until evening when their berries were long gone, staying quiet most of the afternoon. Exhausted, the two fell asleep in the stillness of the afternoon heat, and slept well into dark. The girl snapped awake and prodded Maveith. He woke up as a viper moved through the huckleberry patch. The venomous water viper flicked its tongue in and out and detected Maveith’s body heat. It was dark olive with a blocky head, a thick-body, and a short tail, which differentiated it from nonvenomous water snakes.

“Don’t move,” whispered the girl. “It won’t bother us.”

“I’ll kill it,” said Maveith grabbing his war picks. The girl grabbed his arm, cocked her head and frowned.

“You don’t have to kill everything that scares you,” she snapped. Maveith just stared at her shivering. She left her hand on his bicep as the snake slithered over his ankle then moved on into the forest. They waited a few minutes for the viper to put distance between them and to ensure the clerics moved on.

“I think it’s okay,” whispered the girl as she moved to all fours.

“Wait,” snapped Maveith forgetting to whisper. She looked at him and frowned. “I want to get up first … and put my clothes on.” The girl shook her head and laid back down. “Roll over on your stomach, will you?” he asked.

“Sure,” she said, rolling over.

“Close your eyes.” Maveith crawled out of the hole and stood up. “Not yet,” he said softly. Maveith belted his loin cloth back on. “Okay.” She crawled out and stood up with him.

“That white and gold could have gotten us killed,” she noted. “We have to do something about that.”

“Don’t tell anyone,” he pleaded embarrassingly.

“Tell what?” she asked.

“Who am I going to tell, Butcher? My family’s dead and you’ve left your friends and family behind.”

“Just don’t tell. That’s all.”

“I kept my eyes closed. I didn’t see anything. I promise.”

“Can you stop talking about it, already,” snapped Maveith.

“Okay,” she said. “Let’s get some mud. The girl grabbed his wrist and pulled him toward the river bank. They found an easy slope to the river and the girl squatted. She reached into the water and scooped up a handful of mud, aimed, and threw it at Maveith’s loincloth.

“Hey, what are you doing?” he growled. “You’ll ruin it.”

“I have news for you, Butcher. You’ve done worse than get your precious little Yauuh breechcloth soiled,” she said as she threw another slop of mud.

“Stop it!” he said walking off. She threw another one and hit him on the backside.

“Your pure white garb would have gotten us caught and me killed. We have to hide it.” She stared at him insistently. He looked down at his red-stained palms and mud-splotched breechcloth. It was ruined. Everything was ruined. Maveith squatted down, hid his eyes in his hands and sobbed. The girl stood up and moved closer.

“Get away!” he shouted as he stood up, flailing his arms. Maveith turned and dashed into the woods. The girl shot after him. He ran, stomping like the dwarven soldiers earlier in the day. The moon was a crescent so the forest was dark. Maveith ran through the woods at breakneck speed, his eyesight blurred from the tears. The girl ran after him, treading lightly.

“Maveith, stop!” she unsuccessfully tried to whisper as she ran. Maveith hit a downed tree and flipped upside down, landing on his neck and rolling to his side. He laid on the ground blubbering incoherently, rolling from his side to his stomach. She reached him and stopped. The girl squatted down gently and touched his shoulder lightly. He jerked and wailed.

“I’m sorry I ruined your breechcloth, Maveith,” she whispered delicately.

“You ruined everything!” he shouted. “I wish I’d just killed …”

“Killed me?” she asked. “I get that.”

He buried his face in the ground and bawled. She crawled onto the ground next to him and put her arm around him. “I hate you, too,” she admitted. “But not really. I’m just hurt that my dad is dead. You didn’t kill him. Not really. They did. They lied about him to you.” She started crying, too and buried her eyes into his back.

They laid on the ground and cried for half an hour. She held onto him and covered his back with tears and he wept into the soil beneath him.

“Eleftheria,” she whispered into his back. “That’s my name. Eleftheria.” Maveith rolled over and faced her, snubbing at the end of his cry.

“Really?”

“Yes.”

“I’ve lost everything,” he said. “My family, my friends, my inheritance. All over a girl.”

“No. Not a girl,” she corrected. “Over an idea. You left because you were being deceived.” Maveith nodded and started to sob again. “It’s going to be okay. We will make it. Maveith and Eleftheria. Together.”

“You are all I have.”

“Yeah.” She patted his arm then snapped her head. “Shhh.” She listened and heard murmurs again. The voices came from the bank across the river. The search party moved up the river hours ago and were backtracking. “This place is not safe,” she said. We need to get out of here.” They waited until the voices moved farther south down the bank out of earshot. Eleftheria led Maveith back to the river bank. They crawled into the water and swam to the main shore. They smeared his white and gold tunic in mud until it was as brown as her tunic, ate more huckleberries they found, and headed north along the river bank.

“We need to move at night,” she said. “It will be easier to walk and stay hidden.”

“Sleep during the day?” asked Maveith.

“Yeah, if we can,” retorted Eleftheria.

The walked the rest of the night, following the river bank. Before dawn, they bedded down beneath a white spruce. It’s needles covered the ground, preventing grass growth. They used Maveith’s boot knife to trim some branches underneath making a bit more space. The needles were sticky and sharp on Maveith’s bare skin, but he was too exhausted to care. Eleftheria slept a few hours at a time, but woke with every little sound. Maveith slept more soundly.

He woke up once and found himself alone. He shot up to his feet in a panic and slammed his head into a limb. His eyes darted between the gaps in the branches looking for any sign of Eleftheria. He froze, closed his eyes, and listened. He thought he heard voices, but couldn’t be sure. He was still disoriented from waking up so quickly. One of his war picks was missing. He grabbed the remaining war pick and left the safety of the pine.

Maveith tread lightly through the woods. The pines shed soft needles instead of leaves that turn dry and crunchy, making it quieter to walk on. As he sneaked toward the river bank he knew he heard voices, but they weren’t ones he knew. Maveith snuck slowly until he saw movement through the trees: a man and woman, old, were fishing from the bank. They didn’t use trotlines, so they weren’t fishing for commerce or to feed a large family. That meant they were likely alone, which meant safety. A sound came from behind him. Maveith turned and saw Eleftheria. She joined him, putting her hand on his shoulder.

“They’ve been fishing for a couple of hours,” she whispered in his ear.

“Alone?”

“Yes. Stay here.” Eleftheria patted his back. “Here. Hold my pick.”

“Your war pick?” he retorted.

Eleftheria walked to the clearing and up to the bank. She ignored the couple and squatted, then leaned over to the water and used her hand to bring a drink to her mouth. She drank and scooped more. The couple coughed and she jumped, feigning fear. She turned and looked at them with wide eyes and turned to run.

“Wait, girl,” said the woman. “It’s okay. We won’t hurt you.”

“We’re just too old people fishing,” the old man said. Eleftheria stared at them suspiciously. The couple continued to fish.

“Are you okay, girl?” asked the old woman. “Where are your parents?”

“Parents dead.”

“That happens a lot,” said the old man.

“Are you hungry, girl?” asked the old woman. “We don’t have much, but we have food and shelter.” Eleftheria walked toward the family carefully, watching them. She stopped twenty-five yards and studied them more.

“Why?” asked Eleftheria.

“Why what?”

“Why help me? You don’t know me. I might be evil,” questioned Eleftheria.

“You don’t look evil to me, girl,” said the old woman.

“Maybe I have a friend with me—a butcher—and we will kill you.”

“Do you have a butcher with you?” asked the old man.

“No, but I have my half-brother,” said Eleftheria meekly. “He’s tall.” She pretended to be younger than she was and scared.

“Well, we can feed you and give you a place to sleep for the night if you like.”

“How much?” asked Eleftheria.

“For nothing,” said the old woman. Eleftheria smiled and whistled to Maveith.

“We’ll work for our food,” offered Eleftheria.

“I won’t hear of it,” said the old woman.

“Come, brother,” she said. Maveith left the woods and joined Eleftheria on the river bank. “I’m Nasha and this is my half-brother, Porthos,” she said.

The old people reeled in their fishing lines, packed up and headed back to their homestead. The old woman wore a plain dress with long sleeves rolled up during the hot season. She wore a large, floppy-brimmed farmer’s hat and boots. He wore a long tunic and a similar hat. Their home was a round dome of mud brick and thatch. A stone chimney ran up through the roof. A corral was next to the house with a single mule inside. Around the home was a plot of crops.

“We don’t have much, dear, but we have what we need,” commented the old woman. “Come inside and rest. You look tired.” They followed her inside and sat around a small round table.

It was a simple home, one room with two small beds with an oil lamp between, another bed close nearby, three chairs in front of the fireplace, and a small wood-fired cook stove. The old man sat down with the kids while the woman made tea. She sat the teapot on the table and went back to the cook stove to gut the two fish she and her husband caught and pan fried it with a squeeze of lemon and sprigs of dill. She cut several small red potatoes into halves and fried them in a pan with onion, salt, and more dill. The old man lit a candle and set one in the window and one on the table. Then he grabbed a barrel from the corner and rolled it over to the table. The wife placed the food on the table and sat on the barrel. Eleftheria looked puzzled at the barrel.

“We don’t get many guests out here, dear. We just have enough for us. Isn’t that right, Momma?” said the old man.

“Yes, Papa. We’re simple, but comfortable, and it’s home,” commented the old woman.

They ate dinner and listened to the old man tell stories of his time as a soldier in the militia.

“I barely made it out of that battle alive,” said the old man. “But we won and the town was free from the tyranny of a terrible warlord.” Maveith looked at the floor as the old man spoke. He’d had enough war and death. The old woman noticed.

“Now Pappa, stop scaring them. These kids don’t want to hear old war stories.”

“Of course, Momma. I’m sorry,” he said. “How did you two come to be on your own?”

Eleftheria was a quick liar.

“My brother, Porthos, and I,” said Eleftheria, remembering their pseudonyms, “were working the field with our father when …” she wiped a tear from her eye. “… when our auroch got spooked by a serpent. He ran wild.” She sniffed and touched Maveith on the leg. “He broke the harness to our plow and ran. Daddy was in front and it trampled him to death.” She broke down crying.

Maveith sat. He was not accustomed to lying so he said nothing. He put his arm around her and remained quiet.

“Porthos and I tried to work the field as best we could, but we just couldn’t make it,” said Eleftheria, as she looked into Maveith’s eyes. He shook his head. “We couldn’t pay our taxes to the church so we lost our farm. Porthos and I joined a tribe of wanderers but got separated during a hunt and we got lost. We’ve just been traveling and trying to work for food and shelter.”

“Oh my,” said the old woman. “That is terrible. You poor things.”

A knock came at the door and the man and woman stood up at the same time. Eleftheria and Maveith looked at each other, puzzled. The man walked to the door, moved the bolt, and opened the door. In the doorway stood three dwarves and two behemoths clad in white and gold and holding torches. They walked in and smiled at the kids. Maveith stood up and drew his war pick, followed by Eleftheria. The old woman moved out of the way, grabbing a skillet on her way to the wall.

“No use, Maveith. There’s more of us outside,” said Ilithag, one of the General’s top lieutenants. “Bring her in.” A dwarf escorted a young heavy-set woman with almond-shaped eyes inside the door.

“Momma!” she cried, running to the old woman. The mom wrapped her hands around her daughter and hugged her tightly.

“Is Momma’s girl, okay?”

“Yeth, Momma.”

“You have what you wanted. Now get out of our home,” the old man commanded. Ilithag motioned to a dwarf who threw a sack of coins on the table.

“For your trouble,” he laughed. “Restrain them.”

The dwarves moved toward Maveith and Eleftheria, who surrendered, handing over their weapons.

“I’m sorry,” said the old woman. “We had no choice. They had our daughter.” The daughter had a disability. The third bed and chair suddenly made sense to Eleftheria.

“I should have known,” she said. “No one gives away food without something. When you refused our work-for-food trade, I should have run,” Eleftheria lamented.

Maveith and Eleftheria were restrained well: both hands and feet were locked with iron shackles. The dwarves drug them to a cart pulled by two horses and tossed them on top. Two soldiers rode at the front of the cart and one rode at the back. All were armed and armored.

“The General’s taking no chances,” quipped Eleftheria.

“He doesn’t lose well,” commented Maveith.

They traveled all night, arriving back in camp near evening the next day. During their travels, Maveith and Eleftheria were given two strips of dried meat and three swigs of water each. Whenever they spoke, one of the dwarves jabbed them with a war pick. They pulled into camp and the soldiers hopped out of the cart. Eleftheria was taken to the stockade, shackles still on her wrists and ankles. Maveith was taken to the General’s tent, his shackles still attached.

Ilithag, the large behemoth, pulled back the flaps on the tent and motioned for Maveith to enter. The General stood over a table pouring over maps and battle strategies with his best captains and lieutenants.

“General,” said Ilithag, “I bring back to you Maveith and the girl.” The General stood up tall, clad in his white and gold and stared at his son.

“You bring me shame,” said the General. Maveith’s mother moved toward her son, but the General put out his hand. She stopped and went back to her work. “Leave me,” he commanded. The soldiers filed out quietly passing Maveith. He knew them all. They used to smile and toy with him, but now not one of the commanders would even look him in the eye. “Ilithag. You stay.”

The General walked up to his son. He towered over Maveith, a great man in both size and power. Maveith wanted to look up at his father but he couldn’t. He would cry if he did and that would get him nowhere with his father. So, Maveith looked forward like a strong soldier, still and quiet.

“What did you do?” the General asked. Maveith hurt inside. Guilt, rage, confusion all filled his brain and belly like hot, liquid lead bubbling and burning his guts. He held it inside. “Boy!” the General shouted. “I am your General and your father.” He leaned down and stared into Maveith’s eyes, inches from his son’s face. “You. Will. Speak to me.” The General commanded quietly. His stern whisper voice was the worst. Shouting was normal. Bossing was common. But his quietly controlled commands were the most intense of discussions.

The General was always angry; it was his default. Disappointment, on the other hand, was rare when it came to his children. It was something they all strove to avoid at all costs. Maveith was tired, hungry and thirsty, making it harder to control his emotions. He could feel it all coming out involuntarily like projectile vomit. “Boy, I asked you a question. You best answer me.”

“He was innocent,” mumbled Maveith.

“Who?”

“The man I killed in the circle,” he wailed. The fury he held back wretched out his mouth uncontrollably loud and violent. “He didn’t hold back tithes to Yauuh and the church. He won his gold pieces in a card game against Captain Hergol. Losing made Captain Hergol mad so he arrested that man and his daughter for crimes against Yauuh. It was a lie! A lie! And you made me kill him!”

“I did not lie. He was a dreg, a gambler, a cheater and liar who siphoned handouts off the goodness and hard work of others.”

“He was poor and starving. It’s the only way he could survive!” screamed Maveith. “His wife was sick and he spent everything they had to try to save her! He was a good man.” The General moved to his knees, his face no longer angry but calm and compassionate. He relaxed his brow and his lips smiled. He embraced his son’s shoulders lovingly but firm.

“A good man once, maybe,” said the General. “But he turned from Yauuh and lived a life of unrighteousness. He deserved what he got; it was Yauuh’s plan, son. Yauuh doled out the man’s punishment through his death during your battle.” Maveith blubbered with anger and guilt, tears and snot pouring from his face uncontrollably.

“If it was Yauuh’s will for him to die, then why did he need help?” he screamed, salty tears splattering from his lips.

“What do you mean by help?” the General asked, cocking his head to the side.

“Yauuh didn’t will the man to die. You did. You did!” he continued the scream. “I saw the man’s broken ribs. If it was Yauuh’s will for the man to die, then he didn’t need your help by breaking his ribs.” The General’s eyes widened in shock. He stood up, frustrated, pushing down on Maveith’s shoulders.

“You do not understand, son. The man was guilty. Any other soldier would have defeated him. But you are young. I wanted you to feel strong and keep you safe.”

“But I didn’t beat him fairly. It was all a lie. He should have lived and won his freedom.”

“I am the Cleric General of Yauuh. I know his will and plan. This was good and fair.”

“Lies! Lies!” Maveith sobbed falling to the floor. “It’s all a fraud.”

“I shouldn’t have made you battle. You are too young. I see that now. Your body is more than ready but your mind is not.” The General stared at Maveith. “Do you believe in Yauuh, son?”

“Yes, I think so.”

“Do you believe in me as your Cleric General?” Maveith nodded as he cried. “Then you must have faith that Yauuh’s will was done in righteousness. You are right.” In Maveith’s entire life his father never admitted any wrongdoing. Ever. “I should have made an older cadet fight the man, not you. Then it would have been even and the man would have received his justice fairly. I just wanted to protect you while helping you become a strong and respected leader.” The General turned and sat behind his desk. His mother left her work and rushed to Maveith’s side, holding her little boy.

“I think it’s time you went to the abbey,” he said. “Your mind needs to grow strong before you are ready to take up your divine destiny.” Mother cradled her son and helped him stand. She took him to the other side of the tent, fed him, bathed him, and got him clean clothing. Maveith cycled between moments of anger and sadness but the guilt sat on his shoulders like an oppressive shirt of adult chainmail pushing him into the ground.

Two days passed and Maveith no longer slept hard like a boy. His sleep was light and fraught with sudden awakenings. His chest hurt. His head hurt. The General exempted Maveith from training with the other soldiers. Instead, he assigned Captain Hergol as Maveith’s personal trainer.

“My son knows of your crime against the gambler,” he told the Captain.

“He was a piece of trash. I’m sure he did plenty that he didn’t get punished for,” said Captain Hergol.

“This I know, Captain, but the fact remains that my son is young and your personal indiscretion has caused my son to question the will of Yauuh. And this cannot stand,” he said firmly.

“I humbly repent, General,” the Captain knelt. “And I beg Yauuh’s forgiveness and mercy.”

“My son needs to see Yauuh is a strong but fair god. The man lost his life, but you received no discipline.” The Captain nodded. “You will receive ten lashes from the cat.” My son will execute this punishment. It will help him recover.”

“Yes, General,” relented Captain Hergol.

“And you will privately repent to my son for your personal crimes and the damage you brought to Maveith.

“I will do as Yauuh sees fit, General.”

“Then you will train Maveith until it is time to take him to the abbey. I don’t want him training with the rest of the fresh meat.

“Yes, sir,” said Captain Hergol.

“It’s too much for his young mind. He’s confused and it’s your fault.”

“I will fix it, General,” promised the Captain as the General stared him down.

“Maveith needs to view what transpired, not as a failure of His Holiness the Almighty Yauuh, but as a weakness in you, Captain, that perverted Yauuh’s will. Do you understand?”

“Yes, General.”

Maveith awoke to the sounds of his mother. She was shaking his body and whispering sweetly to him. The tent was dark except for a couple of candles.

“What is it, mother?” he asked yawning.” She handed him his armor and a glass of water and pointed to his clothes. He drank and dressed in silence. She went to the tent flap and threw it open. Ilithag ducked his head and entered the tent.

“Come,” he ordered. “Your father awaits.” Ilithag turned and walked out the tent. Maveith left the tent and followed Ilithag. They walked through camp to the outskirts. Ilithag swung south and headed toward the forest. They walked down into a valley and found a clearing. In the middle of the clearing was a rock circle. Each stone was about two feet tall with a face of Yauuh carved into it. Captain Hergol, the General, and a shaman stood in the center of the circle. Other soldiers stood on the outside of the rock circle.

“You know where we are?” asked the General.

“Yes, General,” said Maveith. “It is a temple of Yauuh.”

“Hallowed ground,” said the General. Few are allowed into the circle. Today, you join us.” Maveith hopped over a stone and joined his father.

“War Priests and soldiers, I have committed a crime against his holy Yauuh. I told a lie in the name of Yauuh and it lead to a death. I am repentant of my weakness and seek forgiveness,” said Hergol.

“Only through blood can we be forgiven,” said the General, and he handed Maveith a cat o’nine tails—a handle with nine, long, leather straps attached. Captain Hergol took off his chest armor and exposed his back to Maveith. “Five lashes is his punishment,” said the General.

Maveith held the weapon and his rage seethed. He looked at Hergol’s back and wanted to see it bloody, but he just stood there.

“It is for you to do, Maveith. He needs forgiveness from you and must pay for his transgressions,” said the General.

“No. I hate him but I won’t beat him. I’m done with giving out punishments,” said Maveith, handing the cat back to the General who refused to accept it. So, Maveith dropped it to the ground and hopped the rocks, waiting for orders from the outside of the circle.

“Yauuh, through my benevolent son, has seen fit to pardon Hergol without physical punishment, said the General. So be it.”

“What of Eleftheria?” asked Maveith.

“Who?” the General questioned. Maveith fumed over the insult.

“You know. The girl whose father I murdered.”

“Not murdered, son,” the General corrected. “What of her?”

“What happens to her?” asked Maveith. The General stood silent. “The same as Captain Hergol?” Maveith asked. He was careful not to plead. The General would see that as weakness. “It might be fair justice under Yauuh’s law, General?” Maveith suggested holding back his emotions. The General squinted and studied Maveith.

The girl is trouble, the General thought. She caused Maveith to think differently, to question. I have to handle this delicately.

“She will receive Captain Hergol’s fate,” decided the General. “It is done. But you must promise to get your mind right and train hard. And never see her again.”