“Who farted?” asked Pim. “That’s nasty!” He pinched his nose and gagged.

“Oh, that was me,” Adrastos chimed proudly. “Isn’t it wonderful?” She was kneeling in the grass on all fours just outside the campfire opposite of Mr. Andvari’s lean-to. To her right, Rarr was laying on the ground playing in the dirt with two rocks and the skull he found. To Adrastos’ left, Maveith sat crisscrossed on the ground. Penelopas was next to Rarr and Pim sat in Mr. Andvari’s lean-to. Rarr rolled onto his back, put his palms to his face and blew hard then roared.

Pim joined in, using the crook of his elbow. Fllb. Thoooof. Pawwl. Adrastos got on her hooves and spun, putting her back to the fire. She flipped her tiny tail in the air and scooted as close to the fire as she could. She ripped gas three times and laughed trying to light her fart on fire.

“That won’t work,” said Maveith. “You have to be closer to the flame.” He stood up and stuck a stick in the coals until it caught fire.

“Seriously?” Penelopas muttered as she rolled her eyes, but they paid her no mind. Maveith brought the stick to Adrastos’ hindquarters.

“Okay, I’m going to get this close. It has to be really close to work. So, be still or you’ll burn off some hairs,” Maveith cautioned.

“How do you know?”

“This isn’t my first time with farts and fires,” he smiled. He placed one hand on her hip and the other held the stick carefully. “Let’r rip!”

Adrastos squeezed off two little poots, then fired a long beast. The flame shot out in a fireball and they cheered, except for Penelopas. Rarr and Pim jumped to their feet and crowded around Adrastos’ backside, chanting “Do it again! Do it again!” The orea repositioned and gave Maveith a nod. He placed the flaming stick at her bottom again and she let another one off. It exploded in a larger fireball this time. Pim shoved Adrastos to the side and pulled his breeches down just exposing his rear.

“I wanna try!” he shouted.

“Okay, okay!” said Maveith. “Hold on.” Maveith moved over and stuck the stick back in the fire to reignite it. “Tell me when.”

“I got one ready!” Pim exclaimed with a laugh. He ripped one off, too. It was the kind that sounded wet, but it worked just as well, shooting a fireball into the night air.

“Ugh!” said Adrastos. “I think you may need to clean up after that one.” She smiled and winked at Pim. He laughed and pulled his breeches up.

“You guys are so immature,” chided Penelopas.

Adrastos moved up for another one. Maveith readied the stick and she blew. It was the longest of them all, shooting a flame out in a straight line rather than a ball. It stretched out then blew back on her, singing some hairs on her rump.

“Ow!” she jumped. She looked at Maveith and they all laughed. “I have a bare spot on my hip now.

“You deserve that for acting so stupid.” Penelopas giggled, her voice was a little louder than her normal whisper. “Now, that was funny.”

“Oh, you don’t like this, Penelopas?” Adrastos turned her back to Penelopas and pooted. Penelopas reared back on her stump.

“You are disgusting!” she shouted.

“If you don’t like hers, maybe you’ll like mine!” Maveith snarked. He turned and farted. Penelopas leaned back farther and fell off her stump. She got up angry, pointing her finger.

“That’s it!” she screamed. The kids froze; Penelopas never spoke louder than a mumble or murmur. “You!” she continued to shout. “You. All.” Penelopas paused …” Deserve this!” She turned and farted in their general direction. Laughter burst out in high pitched preadolescent giggles that carried far into the distance.

“Pipe down!” yelled a man at a nearby camp.

“Causing trouble, I see,” said Mr. Andvari as he approached the campfire, the two girls walking along behind him. The kids sat down, wide eyed at the prospect of getting into trouble for being too loud. “The worst are bear farts. You haven’t smelled anything so foul until you’ve smelled a bear rip a nasty off.” Mr. Andvari said as he shuddered and smiled. The kids guffawed. He motioned for the girls to sit next to him in the lean-to.

“We’re pretty sure Pim made a mess in his breeches,” Adrastos noted.

“Yeah, I better go check that out,” joked Pim. He stood up and left the camp, heading to the outhouse about one hundred yards away.

“I think something crawled up Penelopas and died!” quipped Maveith. “That was pretty gross.” He looked at Penelopas and smiled. She cocked her head to the side and smiled sharply then winked. They talked for a while, laughing about the sticks and fire and the wicked fireballs they created.

Adrastos showed her scorched hip to Mr. Andvari.

“Nice. Boys dig girls with … scars.” He glanced at Penelopas and winked.

They laughed more. The kids were talking. They weren’t just sitting and existing around one another, but were existing together and no one was killing the other. You are getting along, he thought. Becoming a team. This was a good trip.

“How was your night?” asked Pim.

“It was good. I made good trades and made some friends.” He smiled at the girls next to him. “These girls, Ylli and Yolli, are coming back to the abbey with us.” He turned and winked. Yolli was playing with her wooden dragon. “Girls, these are my wards: Penelopas, Rarr, Adrastos, Maveith and Pim. Most of these kids’ parents weren’t nice to them either.” He looked at the wards and they nodded to the girls reassuringly. “You will sleep with the girls, Adrastos and Penelopas, tonight.”

“Welcome to The Leftovers,” Adrastos quipped loudly. Mr. Andvari let out a long sigh.

“We’ll take care of you,” whispered Penelopas.

Mr. Andvari grabbed a five-string banjo, the body of which was made from a gourd. He sat in his chair in the tent and plucked. Penelopas stood up excitedly, grabbed instruments, and passed them out, letting out little squeals as she walked. She didn’t care for military training, par’quor, or many of their other trainings, but music lit her soul on fire. She gave Rarr the drum and Pim the small stringed instrument with a triangular body. Adrastos took the maracas and a clay pot with a small neck. Penelopas gave Maveith a triangle then sat with three flutes and a sitar around her feet.

They played easy songs with simple melodies and a lot of repetition because they were learning and Maveith was new. Pim and Adrastos had been with Mr. Andvari in Panae Hall the longest and had more experience. Pim practiced, but Adrastos spent more time training. Penelopas had not been in Panae Hall very long, but was a natural with any instrument. Maveith tinkled his triangle delicately as he tapped his right foot to the beat. Soon, he was tapping to the off-beat as well. As they played songs, his entire right leg bounced harder—faster—and he clanged the triangle bending the beater until he finally leapt to his feet and shuffled back and forth, moving his hips. They played famous children’s songs as instrumentals, ending with an old Aether folk song, “Sunshine” when Adrastos piped up with impromptu lyrics:

Oh Pim, he blew a hole

Right through his bree-ches.

His fart was wet and wi-ld, too.

He had to go clean up,

Or suffer slimy butt.

And now he sme-ells just like poo.

By the middle of the first stanza, Maveith was dancing as if he was alone—shifting, spinning, moving his hips and shoulders, and bobbing his head. He only struck the triangle intermittently, but when he did, he struck it like a warrior hacking a war hammer at an enemy. Rarr tumbled to all fours and hopped circles around Maveith, hooting and grunting, sometimes leaping into the air. Adrastos finished her lyrics and took breath, but Pim chimed in with his own lyrics, cutting her off.

Adrastos farted, too,

But her’s was nas-ti-er.

It smelled like dead skunk mixed with fish.

She thinks it’s fun-ny,

But we weren’t laugh-ing.

So we plugged her with a stick.

Laughter burst out again and the music stopped. Maveith continued dancing and striking his triangle so the laughter shifted to him. He froze, closed his eyes, took a deep breath, and held it. The wards continued to laugh. Maveith hung his head and moved toward his spot. The man who complained earlier voiced more concern, but this time cursed them in another language.

As Maveith passed behind Penelopas, Rarr somersaulted, then leapt into Penelopas’ arm knocking her backward. She shirked as Rarr landed onto her chest. He leaned down, licked the side of her her face, cackled, then dove off her chest into a somersault around the fire. Rarr popped up near Maveith and lunged into his chest, but the behemoth was unmoved, staring off. Rarr flipped over like a baby in Maveith’s arm and grunted softly, smiling.

“He liked your dancing,” said Penelopas as she sat down.

Maveith looked down and met the feral boys’ eyes. He smiled and grunted back at Rarr. The boy’s eyes blew wide and he gasped with his mouth open. He huffed several times and kicked his legs. Maveith continued to hold him.

“Gia na chorépsete eínai na échoume tin kardiá tou na tragoudísei,” said Mr. Andvari.

“What does that mean?” asked Pim.

“It’s an old Aether proverb,” Mr. Andvari said quietly. “To dance is to have one’s heart sing.” Mr. Andvari glanced at Maveith. Their eyes met. Maveith looked back down at the the little boy in his arms, giggling and grunting. “I’m tired. Go to bed.” Mr. Andvari said sternly but with a grin.

Adrastos sang smilingly, as she escorted Ylli and Yolli to the girls’ pallet.

Pim rose before the sun, stoking the fire to make chicory root brew and later cook breakfast. As the sun peaked over the mountains its warm light filled the lean-to. Erlend always pitched his open-faced tent toward the sun so he didn’t risk sleeping in. Most storms blow in from west to east; one learned quickly to face an open-faced tent eastward. Mr. Andvari rolled over and watched Pim squat down to rebuild the fire with the few coals that remained.

“Morning,” said Pimgin.

“Morning to you, Pim.” He was a pitiful soldier but a dutiful assistant with a knack for intuition and prediction second to none. The best Mr. Andvari ever knew, including himself.

“You kids seemed to have fun last night.”

“Yeah,” Pim said, his eyes still on the fire. “How did you make out last night? Besides the new recruits?” Pim glanced at Mr. Andvari.

“We did well.” He said pointing at two men coming down pulling a cart. Pim turned.

“That cart ours?” Pim asked.

“Yep.” Mr. Andvari rose off his lush bedroll and stretched.

“Ours or the abbey’s?”

“The cart is ours. High Abbess Gudrun has several carts for the the abbey, just not for our use.

“And salt?” asked Pim.

The Abbey has all the salt it needs plus we have salt enough to serve our … uh, extra needs as well.”

“Cooking salt?”

“Cooking, yes. But also tanning, canning, wound care, and still enough left over for trade.”

“Huzzah!” said Pim. “How did you manage that?”

“The girls were in a bad way, Pim. I helped them out. Someone important found out and gave us a real deal in salt if I agreed to take them back to the abbey with us.”

“Will they stay at Panae Hall with us?”

“No, I don’t think so. They will be fine in a regular Abbey room with lots of other girls.” The same sailors who rolled in the barrel the night before pulled a tipcart to camp and set the shafts on the ground. Eight bags of salt and two chests sat secured in the bed. It wasn’t much of a tipcart; it was old and weathered, but it served. The bed was large enough to carry three coffins side by side, large for a tipcart, but the only one Wilendithus owned wide enough for Geros to fit between.

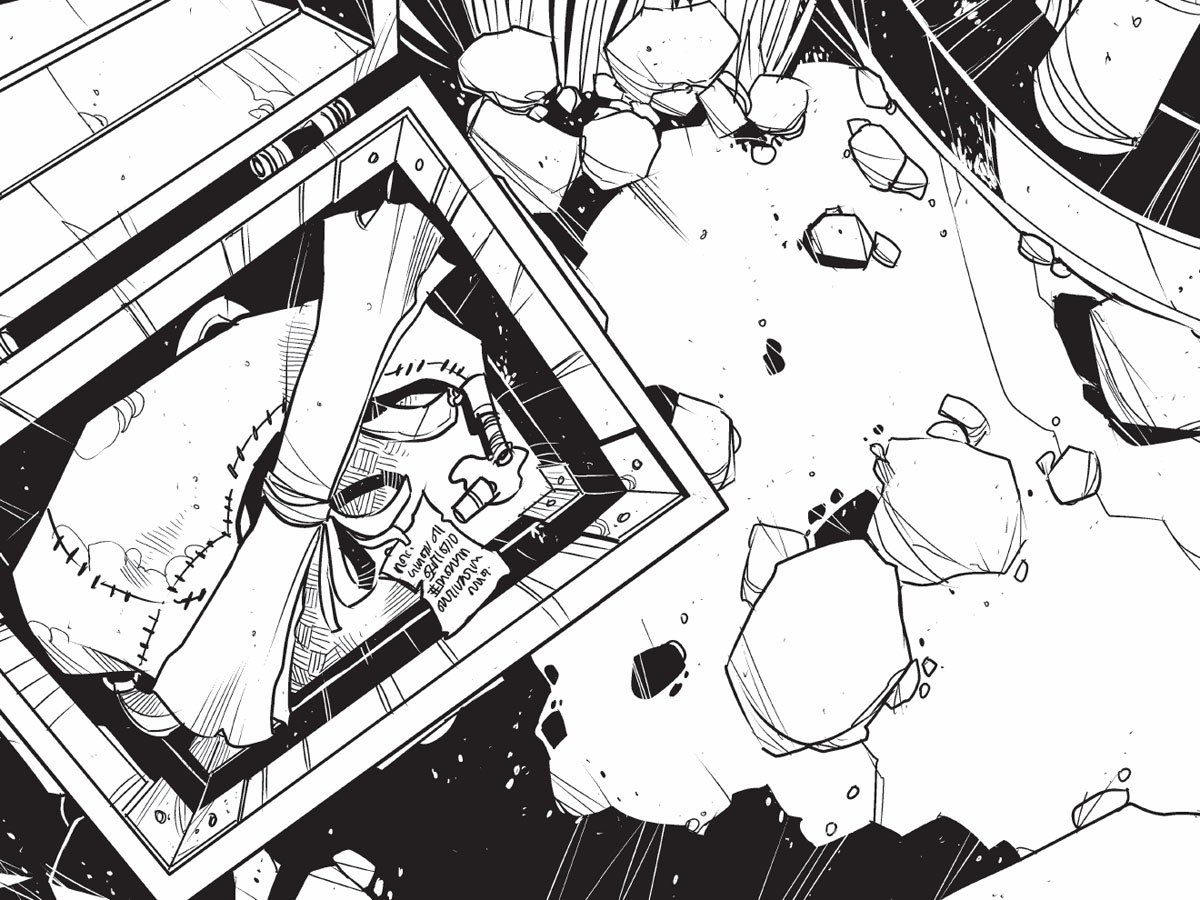

Mr. Andvari inspected the cart and tested the security of the straps holding the salt bags down. He noticed the chests. We only had one chest, he thought. He climbed into the tipcart and unlashed the chests. The one he carried into town was full of salt for Panae Hall. He closed it and opened the second one. His empty wineskin was inside along with a scroll nicely tied with green silk ribbon from which a note was hanging. He delicately united the ribbon and read the beautiful handwritten script:

My Dear Friend Woeltje,

Seeing you again was a welcome delight. I am glad you are well. May this cart serve you and your wards well. I threw in an old map I’ve had lying around for months. I simply do not have time to investigate the legend. I thought you and your wards might enjoy an adventure. If you find the map leads to treasure, I ask only one thing as payment: Bring your wards back to Halibios and regale me with the tale over dinner.

By the way, this letter is in my own hand. Since we last met, I have learned to read and write, even in script. It is all thanks to you. I am forever in your debt.

Your Most Humble Friend,

Willendithus

Mr. Andvari folded up the letter carefully and tucked it and the map in his satchel.

“What’s that?” asked Pim. Mr. Andvari walked away from the cart to pack up his belongings.

“An itemized list of our purchases. That’s all. Let’s get breakfast ready and pack up. I want to leave before the city moves around too much.

Pim stoked the fire, throwing on a couple of dead logs that would burn quick and hot. He pulled avocados out of a cloth bag and felt them. They were soft to the touch, but not mushy. Perfect, he thought, as he cut them in half, pulled out the seed, and scooped out a little more flesh. He cracked a duck egg into the scooped out hole of each avocado half. Then he sprinkled a little salt and pepper on the eggs and put them in a cast iron pot with a concave lid. Pim used a shovel to bring some coals to the side of the fire ring. He set the Dutch oven on the coals then shoveled more hot coals onto the concave lid. As that cooked for about thirty minutes, he cut a wedge of farmer’s cheese and doled out three figs for each of them.

By then, the kids were up and tore down and packed most of camp. Mr. Andvari pulled six hunks of dried fish from his pack and put them in a sack and headed toward the river.

“I’m going to feed Geros some fish. No one follow us,” said Mr. Andvari. “A feeding bear is not a creature to be around, even if it is Geros.” Geros frolicked behind Mr. Andvari, grunting and gruffing, sniffing at the linen bag. At the edge of the water, Mr. Andvari opened the bag and dumped the fish on the ground then immediately stepped away. It’s not raw, but it will do for now. Keep you happy with us and from wandering off with our stuff strapped to your back, he thought. Mr. Andvari left Geros and went back to camp to eat.

After breakfast, the rest of camp was put away and stacked on the cart instead of Geros. By then, the morning sun dried the dew from the tents, making them safe to fold and pack without mildewing, a trick Mr. Andvari learned long ago. Adventurers learned many tricks to survive comfortably and he spent a lot of time teaching his wards the little things that made life smooth and smart. Pim still lashed the weapons to Geros for easy access. Then he and Maveith hitched the cart to Geros.

The bevy assumed the same defensive zone they had when they came to Halibios: Mr. Andvari in front and to the left of Geros with Pim behind him. Penelopas took the left rear near Geros’ hip. On the other side, Adrastos took right point but walked behind Mr. Andvari; she was equal to Geros’ right shoulder. Maveith walked the right rear but farther behind the bear’s hip than Penelopas. Rarr rode where he pleased, moving often. All but Maveith carried a weapon although Mr. Andvari ensured a shield, spear and war pick was lashed to Geros’ right flank, just in case.

They left Halibios by mid-morning, passing under the sign which read: “Now leaving Halibios, Home of the Eisley Salt Mine.” Ylli and Yolli rode in the cart on top of the salt bags. Rarr liked them. They were quiet and unassuming. He sat in the tipcart next to them for the first hour, sniffing and grunting at them, making faces and poking. It was the first time the girls smiled or laughed since Mr. Andvari met them. I wonder how long it’s been since they laughed at all? he wondered. They crossed the dueling mountain ranges and slipped back into the dense forest, following the road.

“We were sent from the abbey to bring back salt, said Mr. Andvari. “Why?”

“Well …” started Pim.

“Not you, Pim. I know you know. I want to hear from someone else,” corrected Mr. Andvari. “Someone demonstrate to me they’ve learned something from me.”

“Salt is good for seasoning food,” said Adrastos.

“Correct. What else?” The bevy was quiet. Mr. Andvari stopped but didn’t turn around. “What else?” he said sternly.

“Disinfectant and medicine,” said Penelopas. “And general cleaning.”

“What else?” Mr. Andvari asked as he started moving again.

“Sorry Adrastos,” said Maveith. “Salt is also used in tanning animal hides and curing meat.”

“Very good,” acknowledged Mr. Andvari. He didn’t praise often for fear of making the wards weak and full of themselves. Acknowledgement was the best anyone usually received. He turned to Adrastos and in a voice that was intended to sound like a whisper but was loud enough for everyone to hear he said, “Looks like Maveith has learned a thing or two about you, Adrastos.”

“Yeah,” she said flatly but she cracked a small grin, which Mr. Andvari noticed.

“Salt normally costs three gold per ten-pound bag,” Mr. Andvari noted. “How many bags of salt do we have back there?” Penelopas dropped back and peered inside the tipcart and counted.

“Eight bags and two chests,” she called.

“Forget the chests for now,” he said. the abbey needs seventy pounds. Panae Hall …” he paused and waited for the snarky nickname, but it didn’t come. “Panae Hall gets ten pounds.”

“That’s eighty pounds total,” said Pim.

“Yes,” Mr. Andvari retorted. “If we pay three gold pieces per ten pounds of salt, how much did we pay altogether for eighty pounds of salt?” He walked and gave them time to cipher.

“I hate this,” said Adrastos. “Just give me someone to fight.”

“Oh, you’ll get in a fight alright, but not for a good reason,” Mr. Andvari said. “If you can’t cipher in your head, then when you get to a market, people will take advantage of you—cheat you,” he cautioned. “Soldier, scholar, monk or magos, everyone needs to do business with others and that means being able to protect your assets from thieves. And not just from pickpockets but the ones who try to trick you.” He stopped talking and gave them more time to think.

“Twenty-one gold pieces,” said Adrastos.

“No, I think it’s twenty-seven,” said Pim.

“I need parchment. I can do it if I have parchment,” said Maveith.

“Yeah. Me too, Maveith,” said Pim.

“One: you don’t always have parchment, ink well and quill with you,” scolded Mr. Andvari. “Two: You don’t always have time to sit down and scribe it out. You have to be able to think on your feet while looking the person in the eye,” he said. “That’s how business is done.”

“I don’t get this,” said Adrastos.

“Hold up eight fingers. Each finger represents a bag of salt,” said Mr. Andvari. He held up eight fingers in the air. “Now, on each finger count three gold pieces.” He counted to three then put down a finger and continued until all eight fingers were down: “3-6-9-12-15-18-21-24.”

“Oh,” said Pim disappointed in his wrong answer.

“At least you answered, Pim,” said Andvari. “You and Penelopas. The others didn’t say because they didn’t know or were afraid.”

“I’m not afraid,” proclaimed Adrastos.

“Yes you are,” said Mr. Andvari. “You are always afraid—afraid to lose, afraid to be wrong, afraid to look stupid.” He stopped, turned and faced them. “You all are. That’s part of your problem. You let the fear of being wrong or stupid or weird…”

“Or Leftover?” snarked Adrastos.

“I am so sick of hearing that word,” shouted Mr. Andvari. He threw his arms to his side and huffed. Rarely did Mr. Andvari get agitated; he always kept his head about him. “You are not leftover.

“But we are. We are this world’s leftovers. No one cares about us!” Adrastos shouted back, her voice wavering slightly.

“No one?” said Mr. Andvari. “Really? No one cares about you?”

“Even our parents don’t want us,” Penelopas said.

“My parents dumped me before I knew them,” said Pim sniffling. “I am literally leftover.”

“I care for you!” shouted Mr. Andvari.

“But you are the only one,” said Penelopas. “And that hurts. Can’t you understand that?” she asked, her words soft and loving but pointed. “You don’t want us to say what we really are as if it’s not true,” she said sweetly. “But it is true. We are Leftovers. The Leftovers of the Iasos Unified Preparatory Abbey. The Leftovers of life. It is what it is.”

Mr. Andvari stood in the road silent.

“I’m tired of pretending that we are something we are not,” said Adrastos.

“He just wants us to be more than …” said Pim.

“No Pim,” said Penelopas. She walked to him and clasped his shoulder. “We can learn and grow. I can take my hood and cloak off. Adrastos can learn how not be a jerk, although that will be hard. You can learn to use a weapon and Rarr can learn to talk. We can learn about salt and ciphering, but we can’t ever be those kids …” Penelopas had tears running down her face but her voice was still humming confidently. “The ones with parents who love and want them. We can’t be recruits at an abbey that doesn’t care about us. Ever. That’s not us.”

“I’m a Leftover,” chimed Maveith. “My parents disowned me.” His hands shook.

“We are all Leftovers, Mr. Andvari. We can’t help it,” said Penelopas as she left her zone completely and walked up to him, staring him in the eyes. “I’m a burned up, scared Leftover that no one but you wants or cares about. I don’t know why you care, but you are all I have.” Adrastos left her zone, too, and clip-clopped over to Penelopas and Mr. Andvari.

“They call us Leftovers behind our backs at the abbey,” said Adrastos. Everyone gathered near Mr. Andvari.

“It’s true,” said Maveith. “They joke about you being freaks all the time.”

“You?” joked Adrastos.

“Us,” said Maveith. “I heard it a lot before I came over to … Leftover Hall,” he said with trepidation as he eyed Mr. Andvari.

“And said it, too, I bet,” said Adrastos. Maveith looked down.

“Yeah, I did.”

“I’m tired of that word being used against us,” said Penelopas. “I’m tired of it having power over us.” Penelopas reached her hands to the edges of her hood and removed it, exposing her leather face mask. “We are Leftovers!” she shouted. “Leftooooovers!” The words bounced against the mountainside and carried into the lake basin louder than she expected. She grimaced slightly at how loud she’d become. “It’s time we acknowledge what we are, at least to each other.” The bevy stood in a silence for minutes wiping tears and muttering awkwardly. The feelings were still raw and unwieldy, almost too much to take for any period of time.

“Okay,” said Mr. Andvari meekly as he turned, nodding his head slightly. “Get in your zones.” He barked but very distantly, obviously still in thought. “We’re gonna get killed out here if we keep causing a ruckus.” He turned slowly, the moment still pressing down on his shoulders and chest. “Move out … Leftovers.”

They marched on silently for miles, the loudest sounds coming from Rarr, Ylli and Yolli, who took on Rarr’s manner of grunts and growls. The little barbarian had never been so still and content around other people. Younger kids were good for him. Before long, his body yearned for movement and he roamed the bevy once again, hopping and rolling from zone to zone, tapping and poking the other wards, growing and howling as he went. He crawled up Maveith’s back once and rode him piggy-back for a long time, softly grunting in Maveith’s ear as if he were telling him a story. Maveith, played along, nodding and responding. “Oh yeah? No way! You don’t say.” The boy was good for the older kids, too, giving them an excuse to play pretend and act silly. All for Rarr, of course, and the new girls.

The bevy turned a bend and noticed a man stopped in the road ahead. He had a flat-bed wagon stacked with cages, pulled by a mammoth slow loris. The creature had wide, sad eyes surrounded with dark rings similar to a raccoon. It had a round face with stumpy nose and nubs for ears. Its fur was short and grey and stood tall on four long legs with toes more akin to fingers on a monkey, allowing it to grasp and hold objects. It had no tail and was the size of a small bear.

Mr. Andvari stopped the bevy, holding his fist in the air. He stood observing his surroundings, listening and watching. The wind was blowing strong through the trees, rustling leaves, and the forest was loud, masking the sounds of the man with the wagon.

Mr. Andvari’s normally relaxed body turned tense and bold like a bristling dog. His keen senses, honed from years of adventuring, alerted him to trouble.

“What’s going on?” whispered Pim. Mr. Andvari shook his head, keeping his eyes on the man who was kicking and cursing at something in the tall weeds along the side of the road.

“Stay here,” he murmured as he turned looking back at the caravan with his peripheral vision. Before he could turn back around toward the wagon man, Adrastos darted forward, pounding her hoofs into the dirt, her trident ready.

The flat-bed wagon was stacked three high and three wide with mediumsized wire cages with starved, rabid dogs inside—fighting dogs. Adrastos spied what was in the cages and went into a rage, racing forward without thinking. Rarr, like Adrastos, spied the trouble and reacted vengefully, launching into the air behind her.

Mr. Andvari lunged forward, reached up, caught Rarr by the loin cloth, and pulled him downward, grabbing his bicep with the other hand.

“Adrastos! No!” he shouted. “Step back, please,” he said after gathering his wits and speaking in a strict, but calm tone. “Rarr. I need you to stay here, please,” he whispered to the boy.

Mr. Andvari turned toward the wagon man. The man was kicking and screaming at a dog lying in the weeds. Blood splattered the blades of grass and wildflowers around. The dogs in the cages were howling and barking incessantly. If they get out … thought Mr. Andvari.

“Pim. Take Rarr. Keep him back.” Mr. Andvari grabbed the war hammer with his left hand and tossed the boy barbarian through the air to Pim with his right hand. Pim caught Rarr, holding him with both hands. Rarr squirmed and kicked, knocking Pim to the ground, but he wrapped his legs around the thin boy and held on. Rarr was surprisingly strong. He broke Pim’s hold three times, but Pim continued to hold him. Penelopas grabbed a strap holding weapons to Geros, and pulled, undoing the quick-release knot. Three spears and a shield crashed to the ground, clanging and banging, ricocheting the sound in a swirl. Great! thought Mr. Andvari. Anyone within one hundred yards knows we’re here now. This is not going to end well.

Adrastos faced Wagon-man, her body standing two feet from his, her trident jabbing into his chest. She was screaming at him. Mr. Andvari raced to her, his hands in front of him, fingers extended, palms out, trying hard to be as nonthreatening as a dwarf with a bear; a restrained barbarian with a war hammer bigger than he was; and a crazed, cursing orea in armor could possibly be.