“WELL,” DR. LAMM SAYS, “THE RASH is finally gone and you’re still peeling.” He lifts my arm up and rubs the skin near my armpit. A tiny shower of flaky skin falls to the floor. I put my arm down quickly, not wanting any of the other thirty kids here to see, but no one even seems to notice. “That’s a good sign.”

“Can I go then?” I ask, wishing that they’d at least let me get back into bed. This cement floor feels like rough ice.

He doesn’t answer, just puts his cold hand up by my throat and presses, which hurts a little. “Greta,” he says to the short nurse, “feel this.” So she puts her hand, much warmer than his, in the same spot.

“Still swollen,” she says.

“So I can’t?” I ask. But he ignores me. For some reason he’s not very friendly today, like it’s my fault I got scarlet fever in the first place.

“Stick out your tongue, Misha.” I do as he says. “Hmm. What was his temperature this morning?”

Greta looks at the small pad of paper she carries around everywhere. “Uh . . . one hundred point two. Down from yesterday.” He looks over at the pad and nods his head.

“Okay,” he says, “back into bed with you.” I cover myself up with the itchy blanket and touch my throat, wondering what they were checking for there. “Once your temperature gets below ninety-nine, you may return to your room. And that might be as soon as Sunday.”

“Two more days?” I ask, and punch the mushy mattress. “C’mon, I’ve been here eleven days already.”

But Dr. Lamm is already at the next bed, where some Dutch girl I can’t even talk to has been for the last few days. She’s asleep, so Dr. Lamm and Greta just stand at the foot of her bed, talking quietly. I have a hunch they’re not talking about her, because I keep hearing them mention other people’s names. Greta shakes her head and stares at the floor. There’s something about the expression on her face I really don’t like, so I look out the window on the other side of my bed, even though there’s nothing to see out there, just the gray barracks and the tips of a couple of naked trees.

I’m so bored I pick up the pad of paper Mother brought me earlier in the week, even though the only thing I’ve done with it is write her one letter. The pen I used barely worked at all, so I had to press extra hard. If I hold the pad up to the light just right, I can still read what I wrote on the page that used to be under the one I actually wrote on:

Dear Mother:

There is a doctor here who once sent me to have my appendix taken out (when I was three I think). There is also a nurse here whose name is Schultz and who knows you. I ate up all the bread, but I can’t make toast here. I am very hungry. The doctor says I’m peeling. What did he tell you? Why doesn’t anyone from Room 7 write to me? Leo Lowy says to send regards to Honza Deutsch. What’s new with Jiri, Kikina, and Felix? Maybe they can all come with you and Marietta next time you visit. I can’t wait to see you.

Misha

“I’m so bored,” I tell Greta about an hour later with the thermometer in my mouth. “Why can’t I go back to my room?”

Greta doesn’t say anything. She reaches out and removes the thermometer. “One hundred point one,” she says to herself and jots it down in her pad.

“I’m serious,” I say.

She looks at me like she had forgotten I was here. “Why don’t you read your memory book?”

“Again?”

“And why not?”

“Because I’ve only had it for a couple of days, and I’ve already memorized the whole thing.”

“Well,” she says, sticking her pen behind her ear, “if my friends bothered to make me something like that, something to remember them by . . .” She blinks quickly a few times.

“Yeah?”

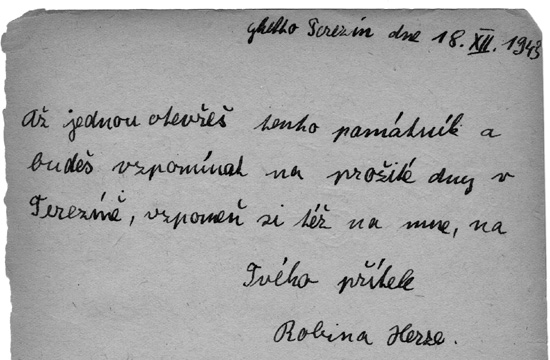

“I’d cherish it.” She swallows and smiles a weird, fake smile. “I would.” She bends over and picks the notebook up from the floor under my bed. “ ‘Memory Book of Michael Gruenbaum,’ ” she reads aloud, admiring the cover, “ ‘Terezin, December 1943.’ They thought of you while you were gone. That boy, what’s his name?”

“Jiri,” I say, annoyed, taking the thing from her.

“He even delivered it himself. Such a sweet boy.”

After she leaves to talk with some younger boy a few beds from me who keeps moaning, I start leafing through the book again. In small, tight letters:

When you open this memory book one day and reminisce about the time we spent in Terezin, think of me too. Your friend Robin Herz.

It is easy to write in a memory book when we live together, but will you still remember me when we’re apart? In memory, your pal, Felix Gotzlinger.

Near the end, in tiny, block letters:

You know what this means, nobody else has to know, and you’ll definitely remember, even when you’re sitting in Prague again. To my close friend, in memory, Hanus Pick.

And a drawing of a soccer ball. I’ll have to ask him what he’s talking about, because I actually have no idea. I close the book and my eyes, then open it to a random page. In thin, curving letters below the drawing of an eagle:

Someday we’ll be back home in Prague, talking about the Nesharim and all our victories. And we’ll still be best friends then, right? In memory, your pal, Jiri Roth.

I set the book down on my lap and stare out the window. It was pretty nice for him to deliver it. And the funny thing is they must have started putting it together before I asked Mother why none of the Nesharim were writing to me, because Jiri brought it by only a couple of hours after someone delivered my letter to her.

I guess I’m not that much better yet, because I slept for half the morning but still feel like I need to rest again.

* * *

Some time later—I must have been sleeping—some other woman walks in and hugs Greta. They talk for a while by the door. Then they hug again. Both are crying. The woman leaves and Greta sits down on a chair, wiping her face with the bottom of her palm. When she gets up and walks toward my bed, I pretend I’m asleep.

* * *

Tap . . . tap . . . tap.

Was I asleep again? And where’s that noise coming from?

Tap . . . tap.

The window. I let the memory book drop from my chest onto the floor. Then I get up and walk over to the window. Tap, louder this time. A small stone, a pebble probably, knocking against the window.

I look out. Jiri’s down below. Three stories below. He waves. So I wave back. He says something, or at least I think he does, because I can see his mouth open, and his breath comes out like a little cloud. But I can’t hear what he says. I hold my hands up to my side and shake my head back and forth. He does this thing with his arms, almost like he’s running in place, his fists making circles by his sides. I shrug my shoulders. He points to his right, then at himself, then out to the right again. Then he does that thing with his arms again and smiles, though it doesn’t look like a very happy smile. I wave and rest my hand against the window, which is freezing.

He stands there for a while, just staring up at me. Then he waves, turns around, and walks away.

I stay at the window until he disappears around the corner of the building. Still trying to figure out what that was all about, I get back in bed. Suddenly I realize he was wearing a backpack over one of his shoulders. I jump out of bed and run to the door. I’m about halfway there when Greta grabs my arm.

“What are you doing?”

“Let me go!” I shout, and try tearing her hand away, which is much stronger than makes any sense.

“Misha, stop, you can’t—” But I finally rip her hand off and run out the door. But as soon as I turn left toward the stairs, I bump right into Dr. Lamm, who accidentally knocks me to the ground.

“Misha?” he says as Greta’s footsteps get closer. I hop up and try to keep going, but four hands are too many for me to escape from.

“Leave me alone!” I scream.

“Calm down,” Dr. Lamm orders. Only I can’t, because I don’t want to. I feel myself thrashing back and forth, and for a split second notice a half dozen kids staring at me from the doorway. Greta puts her arms around me and hugs me so tight I can’t move at all. I want to break free, but my whole body feels so weak I’m scared it’s going to fall apart.

“Shh . . . shh,” Greta says, rubbing my back. “It’s okay, Misha, it’s okay.” And even though I want to push her away and go find Jiri, I let her hold me like that for a while, until I can tell that the kids and even Dr. Lamm are gone. “It’s okay, it’s okay.”

“Is there . . . ,” I start to say a while later, but I still can’t catch my breath.

“Is there what?” Greta asks.

“A transport,” I say to her shoulder. “There is, isn’t there?”

“Yes,” she says into the top of my head after a long pause. “There is.”

* * *

It had to be Jiri’s idea to have them make me the book while I was stuck here. But I didn’t get to ask him, because when he delivered it a couple of days ago, they wouldn’t even let him past the doorway. So we just waved to each other back then, too. Still, I’m positive it was his idea.

Someday we’ll be back home in Prague, talking about the Nesharim and all our victories. And we’ll still be best friends then, right? In memory, your pal, Jiri Roth.

I turn the book back to the beginning, because suddenly I feel like reading through the whole thing again, from start to finish. And there on the first page, which is Koko’s page:

As soon as times are better and we’re home, remember your pal Koko Heller.

Below his drawing of a dog he drew a train, with smoke swirling out of the front. It’s passing a sign that says TEREZIN and is heading straight downhill toward another sign. That one says BIRKENAU, that other name for the East. It better not be so bad there, though right now it’s hard to convince myself it’s anything but.

I close the book very carefully and stare out the window, trying to remember what those taps sounded like, wishing they’d start up again.