“C’MON, TOMMY, PUSH!” I SCREAM from my corner of the wagon.

“I can’t,” he says. “It’s stuck. Look.”

So I walk over to his end to see. The back wheel has fallen a few inches into a crack in the street.

“Maybe if we were coming back from the Dresden Barracks,” Tommy says, “and this thing wasn’t weighed down with all these loaves, maybe then we could lift it.”

“Well,” I say, winking, “what if a few, you know, fall out?”

Tommy’s eyes grow wide. “Misha!” he whispers loudly, “a few rolls is one thing, but actual loaves of bread?”

He’s right. That wouldn’t be the best idea. Because you can hide rolls, especially when your pants, even though you’ve had them for four years, are as loose as mine. But hiding a loaf of bread is another story. Too bad, because yesterday I traded a couple of rolls with a woman for the end of a salami. This is definitely the best job in the whole camp, even if we barely understand anything the Danish men who run the bakery say to us. Plus, Tommy’s really nice and even listens to me, probably because I’m older and officially in charge of our wagon. We get to walk all over Terezin, and a lot of the time we get to choose the route. Also, I was able to get Kikina a job here too, and he won’t stop thanking me for that. Oh, and of course, working for the bakery gets me out of classes. Maybe it’s not so good to be missing so many lessons, but I’ll take being full and stupid over smart and hungry any day.

“What if we rock it back and forth?” I say to Tommy. “Maybe that’ll work.”

We try that for a while, only the thing won’t budge, probably because it’s as long as me and Tommy put end to end. Eventually a man with a mustache and thick stubble walks by, so we ask him for help.

“You two grab that end, and I’ll push from here,” he says from my corner and puts his unbelievably dirty hands near the bottom of the wagon. It takes a while, but after rocking it back and forth about twenty times, we finally lift it up and out.

“Thanks a bunch, mister,” I say after we’ve got it rolling again.

“No problem,” the man says, walking alongside the wagon, like he’s just taking a leisurely stroll with us. We turn a corner and go down a narrow street between two large buildings. “Hey,” the man says quietly, looking behind us, “how about, uh, something for my troubles?”

“Huh?” I ask.

He points at the wagon with his thumb. “Awful lot of bread there. I can’t imagine anyone would notice one less loaf.”

I stop pushing and look at Tommy, who stops pushing too. But he just raises one of his shoulders and murmurs something I can’t hear. So I reach into my pants and pull out a yeast roll.

“They count the loaves,” I say, handing it to the man. “And this tastes better anyway.”

The man quickly grabs the roll and takes a huge bite.

“Hey, mister,” Tommy says, “why are your hands so dirty?”

“Tommy,” I whisper, shaking my head.

“What?” he says back, because I guess he has no idea you shouldn’t say stuff like that, especially to adults.

“Been planting flowers all week,” the man says, taking another bite, “getting our little paradise ready for some esteemed visitors.”

“Visitors?” I ask. “What visitors?”

“Not sure exactly. I hear it’s got something to do with the Red Cross,” he says, talking with his mouth full. “All I know for sure, they’re not painting the barracks and building you kids a playground and installing benches everywhere just because they suddenly decided they like us Jews after all. The only thing they do for us is tell us which train to get on.” He laughs quickly and then cuts himself off. “Seven thousand five hundred people in four days, and the day after that they’re planting grass everywhere, like this is some kind of vacation getaway.” He sticks his finger into his mouth, picks something off his back teeth, and then makes a sucking sound. “Okay, back to landscaping detail,” he says, and starts walking toward where we first met him. “Thanks for the snack, gentlemen.”

* * *

After work and the longest Apel ever (Franta made us hunt for bedbugs, which have been pretty awful lately), I go to the Dresden Barracks. I was able to schlojs half a loaf at the end of work, stuffing a quarter in each pocket, and I want to give them to Mother and Marietta.

Their room is pretty empty. Which isn’t surprising, because I sort of wondered if anyone would be here at all. When I left our building, I noticed a ton of people in the town square, where they never even used to let us go. But they took down the giant tent, and now some orchestra plays there in the evening under the new wooden pavilion the Nazis had us build. And if people don’t like what they’re playing, they can go to the coffeehouse across the street and hear the Ghetto Swingers play jazz instead. The other day I even saw a man play the trombone, which must be the most amazing instrument ever.

It’s like if you weren’t really paying attention, you might think this isn’t just a massive prison.

Marietta is sitting at a table, reading a book. I don’t see Mother anywhere.

I walk quietly over to my sister but don’t say hi, just place the bread over what she’s reading.

“Hey,” she says, annoyed, before she notices what’s blocking her view and who brought it. “Misha Gruenbaum,” she says, admiring the bread, “master schlojser.”

“You’re welcome,” I say. But she doesn’t say anything, just keeps looking at the bread. “Go ahead, it’s yours. I have another chunk just like that for Mother.” Marietta carefully tears off part of the crust and takes a bite. “Hey, where is she, anyway?”

“In bed, I think,” Marietta says, motioning with her head, since she’s already reading again. “Something”—she lowers her voice—“is bugging her. But she won’t tell me what.”

* * *

Mother is in bed, but I missed her, maybe because she’s curled up like a tiny ball.

“Hi,” I say. She tries to smile at me, but it doesn’t really work. “I brought you some bread. From work.”

“Thanks,” she says softly. “But I’m not hungry. You should have it.”

“No, it’s for you,” I say, placing the bread on the thin edge of the bed frame. “I’ll get more tomorrow.”

She doesn’t say anything. Instead she lifts up one of her arms. “Come,” she says. I’m not that interested in joining her, since I know some of the guys were going to play soccer, only she looks so sad. She rolls over a bit, revealing a postcard she was lying on for some reason. I reach out for it, but she snatches it before I can.

“Who’d you get a postcard from?” I ask.

“It’s nothing,” she says.

“Nothing?” But she doesn’t answer. So I grab it out of her hands.

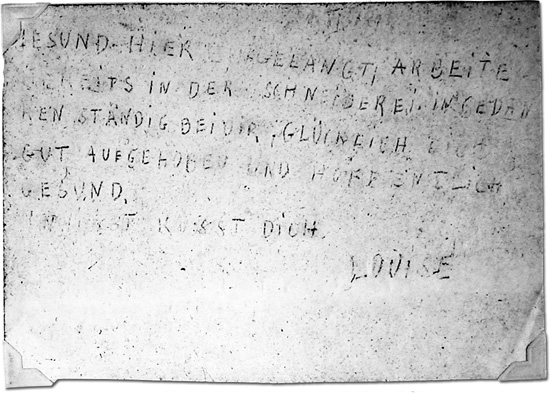

“Misha!” she says, trying to get it from me, but I’m already a few steps away from her bed. Only the postcard doesn’t really say much.

We arrived here in good health and I am already working as a seamstress. Best regards and wishes for good health.

It’s from Aunt Louise, who left on one of the transports with Uncle Ota about two weeks ago. The return address says, “Birkenau.” Other than Mother’s name and the address here, that’s pretty much it.

“What’s the big deal?” I say. “It barely even says anything.” Mother gets up and takes it from me, but still doesn’t answer. “I don’t see why you’re in such a bad mood. She said everything’s fine. Plus the weather is finally warm here and this place isn’t so ugly anymore. Not to mention the air raid yesterday, right? Franta said they were Allied planes. And if they’re flying over Terezin, how far could they be from Germany? I bet we’ll be back in Prague in a couple of weeks. You’ll get to see Aunt Louise then.”

Marietta walks over and pulls the postcard out of Mother’s hand. “Why didn’t you show me this?” she asks quickly.

“It’s nothing,” Mother says, lying back down.

“Right,” Marietta says, “and I’m sure this nothing has nothing to do with why you’ve been in bed since you came back from work. You didn’t even have dinner.”

I look back and forth from Marietta to Mother, trying to figure out what’s going on. But Marietta’s just standing there with her arms crossed, while Mother stares at the bottom of the bunk above her.

“Do you see,” Mother finally says, almost in a whisper, “do you see how the handwriting slants down like that?”

I look at the postcard, the writing is definitely slanting down.

“Yeah, so?” Marietta says.

“We made an agreement. Louise and I. Before she left.”

“What do you mean, agreement?” I ask.

“We knew they’d make them send something like this, so . . .” Marietta has the strip of crust near her mouth but isn’t actually eating it. “If things are good there, she’d write slanting up. Slanting down means things are bad.”

“Bad how, Mother?” Marietta asks. She doesn’t get an answer.

“Maybe she got mixed up,” I say. “Maybe she thought slanting down means good. Anyhow, it says she got a job already. Right? Because how bad can being a seamstress be?” I look over at Marietta for support, but she’s watching Mother and doesn’t seem too convinced by my reasoning. “She arrived in good health. It says so.”

“Bad how?” Marietta tries again.

“Or maybe it’s just a little worse,” I say. “Like, I don’t know, maybe there aren’t any good musicians there. That’s possible, right?”

“Anyway,” Marietta says, “Gustav told me things will be pretty much the same there.” Mother shakes her head slightly and maybe laughs. “What?” Marietta says, sounding insulted. “What makes you so sure he’s wrong?”

“Who’s Gustav?” I ask. No one answers me. “Who is he?”

“My boyfriend,” Marietta finally says.

“Is he tall?” The words come out before I realize it.

Marietta makes a weird face. “What?”

“Nothing,” I say.

“Um, well, yes, he’s kind of tall. But why does that matter?”

“He says it’s okay there?” I ask.

“He’s just a boy,” Mother says. “How could he possibly—”

“Seventeen isn’t a boy, Mother,” Marietta says angrily. “He knows what he’s talking about. And anyway, they haven’t put us on a transport yet, so we don’t have to worry.”

Mother picks up the bread, takes a bite, and chews slowly. “Actually, they did put us on a transport—”

“What?” I ask. Marietta crosses her arms again.

“But I was able to speak with someone on the Council. I reminded them of what Father did for the community back in Prague. They agreed to remove us.”

“When was this?” Marietta asks.

“A couple of weeks ago.” Mother picks up the postcard and sticks it in a thin space between the mattress and the bed frame. “And they . . . they put . . . they put Misha on one a few days later, but I was able to do the same.”

“Just me?” I ask. “Why just me?”

But Mother doesn’t respond, just curls back into the shape of a ball. I almost ask my question again, but in the end I don’t. Instead I just say bye, or maybe I don’t, and hurry out, trying hard to think about nothing but soccer.