5

Safe Environments for Growth, Expansion, and Evolution

Risk more than others think is safe.

Care more than others think is wise.

Dream more than others think is practical.

Expect more than others think is possible.

—CLAUDE T. BISSELL

Rather than make people feel comfortable, we need to make them “safe” to risk change. What’s the difference? Where comfort involves maintaining the status quo, a safe environment empowers people to face the unknown.

We rarely risk possible failure, embarrassment, or mistakes when we’re comfortable. We certainly won’t “take more initiative” or “be more innovative” when our micromanager punishes us for errors or deviations from their way of doing things. That kind of environment makes it more important to be comfortable than to try making anything work better.

But we will risk experimentation, float innovative ideas, and tell the truth—even if it’s unpopular—when we’re in a safe environment. Safety allows us to accept new techniques, try new communication tactics, and tolerate the normal ebb and flow of learning curves, with their built-in slower pace and occasional mistakes.

A safe environment lets people ask questions to gain understanding, resolve confusion, or raise concerns without being ridiculed or told, “You’re not supporting the change!” It lets people support each other, learn and act, surface challenges during implementation, and solve problems together.

In a safe environment, people are acknowledged for the progress they’re making and for sharing their best practices. It’s seldom comfortable, but it can be fun and uplifting.

Improving Morale during Layoffs

How you relate to the issue, is the issue.

—Ron and Mary Hulnick

Nothing is less comfortable than when an organization must downsize. Morale bottoms out. Everyone’s scared or angry or upset—or all three.

It’s the same feeling as when we lose a parent or a spouse or, God forbid, a child. Nothing is okay, and we cannot see how it will ever be okay again.

I was brought in to help improve morale at an organization downsizing about 20 percent of its workforce. It seemed a strange request, as morale naturally drops when people fear losing their jobs. I thought their anger about their situation was perfectly reasonable, especially since it manifested in all the typical ways. Some people got into major verbal fights with their peers. Others simply “checked out” and didn’t bother completing their work, which caused breakdowns for those still trying to serve customers. Even though some managers would also be laid off, management and employees became polarized. The environment grew toxic and painful.

How could I make anyone comfortable with such a negative situation? Those whose jobs were secure felt not only guilty, but stressed—they knew they’d soon have to do three people’s work.

I knew change had to start with a different mind-set and habit of response. I also knew I’d have to modify the B State approach to address the current negativity, because it’s not the demanding situation that gets people upset; it’s the way they perceive and react to that situation.

The company didn’t bring me in before things went sour—they didn’t think about fixing things until they were already thirty days into the threemonth layoff period—so I began by telling one group of very angry and distraught people the truth.

“The company will do more downsizing over the next two months, and there’s nothing I can do about that. Some of you will be laid off—and there’s nothing you or I can do about that, either. So, you each have a decision to make: you can stay angry about the change and keep taking your frustrations out on each other—which will just make this change all the more difficult and unpleasant for everyone—or you can support each other through it. Your choice.”

No one said a word. They all looked shocked that I would propose this choice. Then one person spoke up.

“Do you think we can support each other through this mess, for real?”

“I don’t know,” I said with perfect honesty. “It would be an experiment. What I do know for sure is if you keep blaming management and exacerbating all the negativity in this situation, you will keep being miserable. In that case, you don’t need my help—you’ve already nailed upset and anger—so we’ll call this meeting over. On the other hand, if you decide to support each other, I’ll stay and guide you through creating a supportive environment.”

I stopped talking, sat down, and waited. And waited. And waited. I knew they had to choose their own empowerment and ownership without me encouraging them to do what I thought best. Finally, someone said, “I guess we have nothing to lose. Let’s see what it means to support each other.”

Good! “So,” I asked the group, “what would you need to do differently to support each other through the layoff period?”

“We need to accept that different people will have different reactions during the transition,” one person offered, “and we need to honor those responses.”

I wrote that on the flip chart. “What do the rest of you think?”

“We need to stay focused on our job and support those who are struggling that day.”

I wrote that down, too. They didn’t know it, but we were creating a B State Team Agreement.

“If someone loses their job,” a third person said, “we’ll all use our networks to help them find a new one.”

I felt the energy of the group begin to shift and relax a little.

“Sometimes, I need to vent my emotions and frustrations,” someone else said. “I just need to let off steam.”

“Okay,” I said, “but there have to be some guidelines. You can only choose one person as a sounding board, and you must ask permission for a one-minute venting period during which you can express anything freely—with any language—without fear of judgment or repercussion. Afterward, you must go back to work.”

Everyone applauded.

Someone raised a hand. “In the past, when I got restructured into a new team, my old team cut me off from social events and information sharing. I felt abandoned. That made everything harder, because I’d lost my old team but hadn’t yet been accepted into my new one. I couldn’t afford to quit—and my wife said I should just be thankful I still had a job. But I was miserable for a long time.”

“Let’s add that condition,” I said as I wrote. “If anyone is transferred to another department, the team will stay connected and include them in regular social activities.”

“We need more information from management to prevent rumors and keep us from feeling helpless and out of the loop about what’s happening,” someone put in, carefully not looking at the management-team leader in the room.

“How about this?” the leader responded. “Let’s have a five-to-ten-minute get-together every morning so I can keep you up to date about what’s going on and address any rumors you may have heard.”

“That’ll be okay,” said a team member, “if, at the get-together, we can also ask for some support without being blamed or ridiculed. I know some of us just need to be left alone, but sometimes a little conversation, or even a hug of reassurance, would be an immense help.”

By the time we completed the B State Team Agreement, everyone felt they had a safety net to get through the next two months. More upbeat and at ease, they formally documented the agreement. They got together to review it each week, and as they each felt their teammates’ support, morale rose. Later, near the end of the layoffs, one team member told me, “Our morale is higher now than it ever was, even before the downsize. We’ve never been so supportive of each other. There were always cliques and blame-game fights between people. Now we support each other emotionally, and we’re performing better than ever! We don’t have the breakdowns and communication problems we used to have. When there’s a problem, no one is afraid to talk about it, so we resolve it instead of letting it fester. And our last customer-service scores actually went up!”

I was delighted, of course, especially since I got similar reports from all the teams we worked with during the downsizing. I’ve since been asked to create the same kind of safe environment in numerous other companies—in many countries and cultures—as they, too, went through the discomfort of downsizing and restructuring, whether as the result of economic conditions or acquisition.

B State Team Agreements

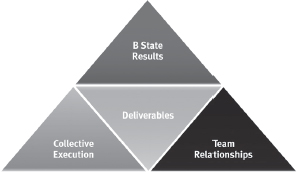

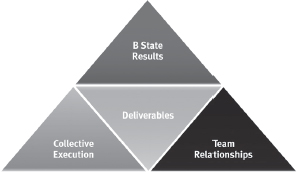

Figure 4: B State Implementation Model

Courage starts with showing up and letting ourselves be seen.

—Brené Brown

Building trust, support, and effective communication is not a one-size-fitsall process. The Gen Z “mass personalization”—individualized products and identifications on a massive commercial level—recognizes how we’re all individuals with unique needs, beliefs, and behaviors that cannot simply be narrowed down to sixteen styles or other forms of typecasting. The B State, too, recognizes that most people will never accept or adhere to generic team guidelines and core values. That’s why every B State Team Agreement must be unique for its specific team and based solely on everyone’s needs in relation to the team.

Ergo, those Team Agreements will change over time as teams and members evolve.

A twenty-person extended-management team had low scores in trust, communication, and decision-making. I clearly recognized the problem after observing just one meeting: five people did all the talking while the others remained silent, and everyone was upset about it. The five resented the others for not speaking up, and the others resented the five for dominating every discussion.

“What can you do differently to ensure better team communication in your meetings?” I asked the group.

“Every team member needs to commit to voluntarily share their ideas and opinions on every discussion in our meetings so no one dominates, and everyone feels heard,” one of the five said.

“That’s a big commitment,” I said, writing his statement on the flip chart. “Does everyone else agree this is a good idea for your team?”

“Yes,” several people responded simultaneously.

“It’s the only way we can ever change this team’s dynamic,” one of the fifteen quiet members said.

“What will you each—individually—need to feel safe enough to share your ideas openly in team meetings?”

“No put-downs or attacks for what we say,” a second “quiet” member offered.

“Openly listen to each other without judgment before responding,” said a third.

As they all individually shared their concerns or needs, I added them to the agreement in a separate “Conditions for Acceptance” section.

“If you’re going to openly listen to people’s ideas and input, what do you need in order to make sure this is practical for you and your team?”

“Stay on topic rather than move to tangents.”

“Don’t go on and on repeating yourself over and over again!”

The entire team cracked up in laughter.

“Okay, good work, everybody,” I said. “We need to take our afternoon break. When we come back, we’ll complete the agreement.”

Ann pulled me aside during the break. “Can I talk to you?” she asked. “I really like this agreement and process, but . . . I’m extremely shy. I can’t keep to this agreement as it’s written in good faith. Can you bring this up for me when we go back?”

“I understand your concern,” I said, “but if you think about it, you’ll see why I can’t surface this for you. You have to do it yourself.”

She looked down and shook her head.

“What I can do,” I hurried on, “is help you to surface this with the group. I’d be happy to do that.”

She smiled. “Okay!”

I kicked off the after-break discussion: “Ann has something she wants to share with all of you.”

Ann shot daggers at me with her eyes. Okay, that wasn’t very nice—but after taking a deep breath, she did manage to say, “As you all know, I am . . . very shy and . . . introverted. This agreement says we will volunteer our ideas and input—I . . . I can’t do that.”

When no one responded to her, I asked, “Can you still have this agreement but make an exception for Ann?”

Bill turned to her. “If we want your idea or opinion, can we call on you to share it with us openly?”

“Yes! Absolutely! I totally commit to sharing openly—just not voluntarily.”

“Then I’m okay with those conditions,” Bill said. “What about the rest of you?”

Everyone agreed. Like most people, they hadn’t realized agreements need not be uniform or boilerplate. The team could make exceptions for individuals without relinquishing the agreement’s intent.

The manager, one of the five “speakers,” said, “You know what? This is the first time I’ve seen true diversity demonstrated—not by race, religion, or country of origin, but individually, based on us all being unique. This is a real demonstration of support.”

When an issue was surfaced at our follow-up session six months later, sixteen of the twenty team members actively and openly shared—quite an improvement from the original five.They were at the next development stage, where they wasted time in endless debate. That’s the natural human growth process; solving one problem creates the next higher level of problems. I was about to make this a learning moment when Ann slammed her hand on the table and stood up.

“We’re going around in circles!” she shouted. “We’re not getting anywhere! We all need to take a breath!”

I looked around expecting everyone to be as shocked as I was by this shy, introverted woman’s outburst, but they all just sat quietly.

“Did anyone notice anything peculiar about what just happened?” I prodded.

Everyone looked at me in silence.

“Didn’t anyone notice Ann’s behavior?”

Still no response.

“You had an agreement that Ann wouldn’t volunteer her opinion until asked,” I pointed out. “Yet she just slammed her hand on the table and shouted at all of you.”

“Oh, yeah,”one team member said. “Heck, Ann stopped needing that condition three months ago. Now we can’t keep her quiet. She talks all the time.”

I was the one who learned a lesson that day: when people create a truly “safe” environment, they can evolve past their previous labels, styles, and inhibitions to participate with greater courage and confidence. Forming B State Team Agreements isn’t about following the rules. It’s about learning how to create a safe environment, so people can evolve to higher levels of trust, support, and transparency.

Families Need Safety Too

Trust is the glue of life. It’s the most essential ingredient in effective communication. It’s the foundational principle that holds all relationships.

—Stephen Covey

A friend asked me to facilitate a B State Team Agreement with his family. He was frustrated that his teenage son and daughter acted out during dinners at home, during family get-togethers, and when asked to do chores.

I started by asking each person, “What is one thing you’d like to see changed in your family’s expectations and communications?”

“I want more cooperation and participation in family activities from my son and daughter,” Dad started off.

“I want less fighting and yelling,” Mom stated.

“What do you guys want?” I asked the kids.

“I want more time with my friends,” Megan said.

“I want to be left alone to play my video games,” Tommy shared.

On the flip chart, I wrote:

Each family member contributes to the togetherness of the family and supports each person’s individual interests in a balanced manner while effectively communicating and listening without shouting.

“Do you agree with this basic statement?” I asked.

“Yeah,” Megan said, “but we don’t know how to do that.”

“That’s okay for now. What do you think is a reasonable time for family contribution, and how do you think it should work?”

“I think we should get to split our time for dinners fifty-fifty, so we sometimes eat together and sometimes eat with our friends,” Megan said. “And we should have set times for doing chores so we can plan when we can be with our friends ahead of time.”

I wrote down those conditions for acceptance. “Anybody else?”

“I’m okay with what Megan said,” Tommy put in, “but if I’m in the middle of a game, I want to finish it before coming to the table.”

“Wait a minute,” Mom interrupted. “I don’t want dinner to get cold. I think we should have a set time for dinner and you plan your time to be there.”

“I guess that’s okay,” Megan said. “If it’s really going to be the same time every day instead of whenever Dad gets home. Tommy?”

“Okay, I can agree with that.”

“But I can’t get home at the same time every day,” Dad protested.

“We all understand that, but I think the three of us need more consistency at this point,” Mom said. “And if we schedule dinner for 6:30 every night, you’ll make it three out of five nights—and when you can’t, you’ll know we’ve already eaten and will have to make do with leftovers.”

“All right, I can go along with that,” Dad said. “But what frustrates me is that no one listens when they’re called.”

“Instead of voicing your frustration,” I put in, “what do you want, and what do you think is reasonable?”

“Sometimes I can’t get Megan or Tommy’s attention when I want to talk to them about something. I want them to listen and help me out if I need them. Right then. Not later.”

“What do you think about that?” I asked the kids.

“If it isn’t at a scheduled time,” Megan said to her father, “then I’m probably doing something else, so you’re interrupting me. I think I should be able to finish whatever I’m doing before I have to respond.”

“Do you think that’s reasonable?” I asked Dad.

“I suppose—but you could at least let me know you heard me and how much time you need before I can get your attention.”

“What do you guys think?” I asked. “Is that reasonable?”

“Okay,” Megan said. “I’ll commit to telling you I’m busy and when I’ll be available.”

“Me too,” Tommy agreed.

“But we all make mistakes,” Mom put in. “What can we do so we don’t end up fighting and yelling?”

“Great question!” I said. “What are you going to do differently when you get frustrated?”

No one answered. This is where they got stuck.

“Let me offer a suggestion,” I said, “and you can massage it afterward. Since this is a change for everyone, let’s not expect perfection. How about if you all commit to a once-a-week family meeting at one of your family dinners to review this agreement and discuss whenever anyone felt a lack of cooperation. You’ll either get back to the agreement as it is, or work together to resolve whatever caused the problem. If you break the agreement, you’ll voluntarily admit you messed up—and that’s particularly important for you two, Mom and Dad. You’re the ones who create or destroy the safety. No one needs to be in this alone. You’re a great family. You can work out your differences together. How does that sound to everybody?”

Everyone was excited about a weekly family meeting except for Tommy— but he did agree to support everyone else.

“You just have to include one more condition,” I said. “No yelling—okay, Dad?”

“Fine, I won’t yell—but only if we all keep to this agreement!”

“Good. But yelling is an old, ingrained habit for you, so what can they say or do that won’t set you off even more—if you start getting louder and more intense?”

“Just say, ‘Hey, you’re getting intense; take a breath,’ and I promise to bring it down.”

“Promise?” Mom asked.

“Yeah, yeah.”

I reviewed the agreement with every condition and asked each person to give their commitment. They all said yes and looked much more positive and relaxed than when we first sat down.

When I checked in with them three months later, they had figured out that just keeping to the agreement wasn’t what made things work—it was what happened when someone didn’t keep their commitment that mattered. They didn’t yell, blame, fight, or hide. When schedules changed, they modified their “family time” together. And they were all much better about owning up to their mistakes and giving and receiving forgiveness.

They had become a B State family.