Chapter Four

The Task Force Prepares

The Argentine invasion, although it took the public, Press and Parliament almost completely by surprise, did not find the Royal Navy and Ministers altogether unprepared. The Commander-in-Chief’s staff at Fleet headquarters, at Northwood, had been taking precautionary measures since 29 March, when it first became apparent that diplomacy might fail to find a solution. In Whitehall, the Navy Department* had not long since conducted a procedural exercise which had covered many aspects of the swift mobilization of the Fleet and its deployment, so that not only the key permanent staff, but also the ‘augmentees’ who would be called in to reinforce them, were well acquainted with the necessary routine.

The order on 1 April to bring the carriers to 48 hours notice for sea began the process. HMS Hermes and Invincible had been involved in major exercises in February and early March, the former acting as an assault ship with 40 Commando RM, twenty-nine helicopters and five Sea Harriers embarked, and the latter as an anti-submarine carrier with a standard load of nine ASW Sea King Mk 5 helicopters and five Sea Harriers. Both were now at Portsmouth, the Hermes in the second week of a six-week ‘Dockyard Assisted Maintenance Period’ with most of her major systems opened or dismantled for maintenance and the Invincible with her ship’s company on leave, but otherwise more obviously ready for sea. Also at Portsmouth were the two assault ships, Fearless and Intrepid; the Fearless had also taken part in the annual amphibious exercise off North Norway, supporting 42 Commando, but she had reverted to her normal role as the officer cadets’ and midshipmen’s training ship. HMS Intrepid had actually paid off, her ship’s company had dispersed to new jobs and she was being de-stored in preparation for reserve or, possibly, disposal. Already in reserve was the RFA Stromness, a fast stores replenishment ship which was also to play a major part in the forthcoming campaign.

While the Dockyard, the Fleet Maintenance Group and the ships’ staff hurriedly buttoned up first the Hermes and then the Fearless, rectifying all known defects, the Naval Stores and Transport organization began the colossal task of preparing the ships not just for sea but also for a long deployment. Food – fresh, tinned, dried, frozen – clothing of all types, thousands of individual stores and spares items for the different classes of ship and versions of equipment, ammunition and ordnance in larger quantities than had been known since the end of the Second World War and fuel of three main types (‘Dieso’ for the gas turbines of the most modern ships and the boilers of the Type 12 and ‘Leander’-class frigates, ‘FFO’ for the older steam-driven ships and ‘Avcat’ for the aircraft) all had to be loaded, not only into the ships before sailing but also into their accompanying replenishment RFAs and the ships which would keep the RFAs topped up. The Supply Officers of the individual ships assisted by making up their ‘shopping lists’ – in itself a complex task – and the stores arrived from all the various depots, by rail, by the Ministry of Defence’s own transport fleet and by commercial vehicles. Particularly urgent items were flown to nearby airfields and were then delivered by helicopter to the Dockyards or direct to the ships.

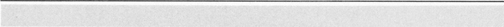

Storing HMS Hermes for the South Atlantic while work over the side continues – an old-fashioned ‘humping’ party passes boxes on the starboard forward gangway, side-by-side with a mobile conveyor belt (MoD)

To clear the mountains of stores which rapidly built up all available Service manpower was called in to work around the clock: at Portsmouth, the RN Display Team, the Field Gun Crew and the tenants of the Detention Quarters, as well as personnel from nearby naval establishments, worked alongside the ships’ parties and the Dockyard Stores men who would normally have undertaken the job. As the jetties were cleared of stores, so the debris mounted – discarded transit crates, packing cases and boxes – and such was the preoccupation with loading that clearing-up could not begin for a fortnight.

The Dockyard at Gibraltar, run down over the years and scheduled since July, 1981, for closure, could not provide the range or quantity of material required to stock the seven ships which were to form the first ‘wave’. Rear Admiral Woodward, flying his flag in the ‘County’-class guided-missile destroyer Antrim, took what he could but then had to pair off his ships with those which were not allocated to the force, the outbound vessels taking provisions, ammunition, spares and, in at least one instance, personnel on board. With five different types, most of the transfers were between dissimilar ships, the ‘Leanders’ Ariadne, Euryalus, Aurora and Dido serving, respectively, the Antrim and her sister-ship Glamorgan and the Type 42s Coventry and Glasgow; the Type 21 frigate Active supplied the Sheffield, while her sister, HMS Arrow took what the Euryalus and Dido could spare after they had looked after the destroyers. Only the two Type 22s, Battleaxe and Brilliant, were evenly matched, to provide the latter with everything that could be spared or, if necessary, detached.

The transfer was made more straightforward by the number of helicopters available. Every ship had an embarked flight – a Wasp in each of the ‘Leanders’, a Wessex in the ‘Counties’ and a Lynx in the others (two in the case of the Type 22s) – and the helicopter support ship RFA Engadine was on hand with her Sea Kings. There was even a spare deck capable of operating the big helicopters if need be, on the accompanying fast tanker RFA Tidespring.

The destroyers and frigates stored throughout the day, heading away from Gibraltar. There were three more frigates in the base, Plymouth, her sister-ship Yarmouth and the Type 22 Broadsword, all of which had been taking part in the now-abandoned exercise. The first was due to begin an Assisted Maintenance Period which would take several weeks and a number of families were due to fly to Gibraltar to join their husbands: the Plymouth was ordered to join Admiral Woodward’s group and sailed on the 2nd with RFA Appleleaf, leaving the Broadsword with a list of those to be contacted and told not to come. The Broadsword and Yarmouth remained at Gibraltar to make final preparations before sailing for the Indian Ocean, where they were to relieve the patrol at the entrance to the Persian Gulf. HMS Sheffield had been returning from the patrol when she joined the exercise and was then despatched to the South Atlantic, in the wake of the RFA Fort Austin, which had been one of her support ships: the other, the tanker Brambleleaf, was detached from the Indian Ocean to join the Falklands operation by way of the Cape of Good Hope.

The whereabouts of the submarines was exercising the media. The nuclear-powered Fleet submarine Spartan had embarked stores and torpedoes at Gibraltar and had sailed on 1 April and the Splendid sailed from Faslane on the same day. The Press was not told of these deployments, but correspondents learned that the Superb had sailed from Gibraltar and came to the wrong conclusion: in fact, she was returning to Faslane, although that was not made public for several days after her arrival. In the meantime, HMS Conqueror had left Faslane on 4 April, also bound for the South Atlantic.

Storing continued on Saturday, 3 April in the Dockyards. The Prime Minister, in the House of Commons, announced the formation of the ‘task force’ which was to be despatched to recover the islands. The force now included 3 Commando Brigade RM, which comprised 40, 42, and 45 Commandos RM, the Commando Logistics Regiment RM and No 29 [Commando] Regiment, Royal Artillery. To these were added the 3rd Battalion of the Parachute Regiment and a dozen Rapier surface-to-air missile launchers of ‘T’ Battery, 12 Air Defence Regiment, RA. Even though almost all the available amphibious assault shipping would eventually be deployed, this would not be able to carry the 3,000 Marines and soldiers and personal weapons, let alone the tens of thousands of tons of vehicles, heavy weapons, spare equipment and, above all, rations and ammunition. Moving the men was relatively simple, the material was not: the seventy Volvo over-snow vehicles came down from Arbroath to the south coast by rail during the weekend, as did 3 Commando Brigade’s reserve ammunition, but not all units could find rail transport and the roads to Portsmouth, the Royal Corps of Transport marine base at Marchwood, on Southampton Water, and Devonport were the scenes of activity not seen since the end of the Second World War. A deadline had been set for the sailing of the force and as, for various reasons, this could not be missed, the ships were not all ‘combat-loaded’ to be able to supply the troops with material in the right order in the early stages of the landings.

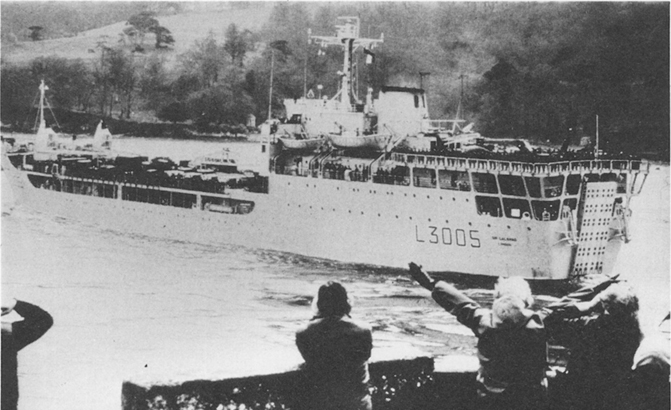

The ships immediately to hand were the Fearless, which would serve as the headquarters ship of Commodore M. C. Clapp, the Commodore, Amphibious Warfare,* and Brigadier J. H. A. Thompson OBE, commanding the reinforced 3 Commando Brigade, and four Landing Ships (Logistics) (LSLs) Sir Geraint and Sir Galahad at Devonport and Sir Lancelot and Sir Percivale at Marchwood: all these LSLs were manned by the RFA, with British officers and mainly Chinese ratings. The Intrepid was now being recommissioned, with her former crew who were haled back from leave and new jobs. Sir Tristram was in Belize and would catch up during the passage south but the sixth LSL, Sir Bedivere, was at Vancouver and would be unlikely to take part in the early stages of the amphibious operation. It was decided, therefore, to bring the RFA Stromness back into service to serve as an assault platform in the initial stages and then in her stores support role.

There was still insufficient troop and military transport lift capacity and so, on 3 April, the necessary Statutory Instruments were signed to permit the Navy Department to take ships up from trade. Almost the first to be ‘STUFT’ was the P&O flagship Canberra, homeward-bound with a load of passengers on a cruise, who were to be replaced by two Commandos and 3 Para. Much of their heavy equipment and ammunition, as well as eight light tanks of the Blues and Royals, would go in the ‘Ro-Ro’ (roll-on/roll-off) ferry Elk.

Additional logistics support was also needed and nine British Petroleum tankers of the ‘British River’ class were taken up. Two of these, British Tay and British Tamar, had already undertaken trials to evaluate their suitability as ‘Convoy Escort Oilers’, but for the time being their main task was to supply the RFAs in the forward areas. Liaison teams from the RFA were provided for these ships to enable them to work with the practised auxiliaries and the Navy.

The helicopters began to embark in the big ships on 3 April. The antisubmarine Sea Kings of 826 and 820 Squadrons went to the Hermes and Invincible, respectively, and were joined in the former by the ‘Commando’ Sea King Mark 4s of 846 Squadron. The ASW squadrons would fly all round the clock and were relatively well-off for aircrew, 826 Squadron, for example, having fifteen full crews (each consisting of two pilots, an Observer and a sonar operator) for nine aircraft. The assault helicopter squadron, which would have twelve aircraft when brought up to full strength, had a much smaller surplus of experienced pilots and no spare cabin crewmen.

The Sea Harrier squadrons had begun to arrive on 2 April, eight Sea Harriers being flown on to the Hermes as she lay in the dockyard. Three more arrived on Sunday the 4th, while Invincible’s complement of eight flew in on the same day. As originally formed, the two squadrons, 800 in Hermes and 801 in Invincible, had only five aircraft each, but by absorbing the ‘headquarters’ training squadron (899), calling forward reserve aircraft and impressing a trials aircraft from the experimental establishment at Boscombe Down, a total of twenty fighters was put together. Maintenance crews were found for the enlarged squadrons, but such was the shortage of pilots that, in spite of the attachment of seven fully-navalized Royal Air Force pilots, two pilots who were still undergoing operational flying training were also taken along, to complete the course en route.

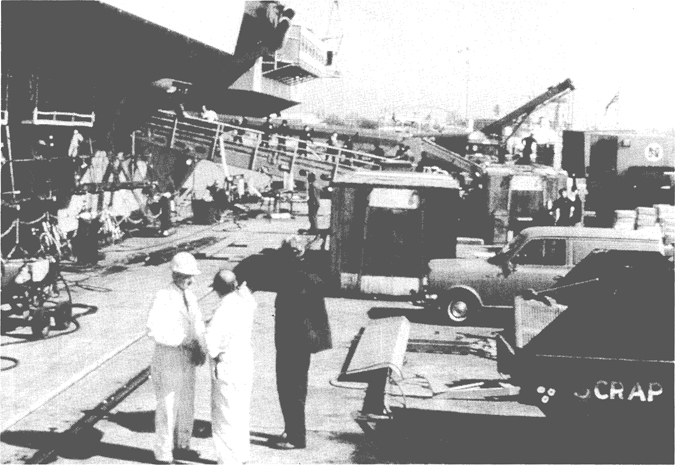

From the very outset of planning Ascension Island had been intended for a most important role. Roughly halfway between the United Kingdom and the Falklands, it could provide a forward anchorage and, thanks to the 10,000-foot runway built by the US Government, a major logistics base for receipt and despatch of men and material by sea and air; the first air support movements – four Lockheed Hercules from RAF Lyneham – took off on 2 April. The Wideawake airfield was operated by Pan American Airways, whose US Air Force contract allowed for 285 aircraft movements per year, in support of Ascension’s very mixed working community, which included the US National Aeronautics and Space Agency (NASA), the BBC and the Cable & Wireless communications company. A hundred years before, the Admiralty had built a sizeable base, with accommodation, workshops and even a hospital, but this had not been used after the First World War and, even at its height, the base had never boasted more than a small stone jetty for use by ships’ boats and lighters. The anchorage off the jetty is subject to a long, heavy and uncomfortable swell, as are ships, which must lie between a quarter and a half mile offshore. In such unfavourable circumstances, helicopters were to play an essential part in ship-to-ship and ship-to-shore movements.

The backbone of the stores ‘air bridge’ between the United Kingdom and Ascension was provided by the Lockheed Hercules medium transport aircraft of the RAF’s Lyneham Transport Wing. The majority of the 13,000 hours flown by the four squadrons of the Wing were accumulated on the northern sector, but the longest sorties flown were by the probe-fitted aircraft flown by No 47 Squadron RAF between Ascension and the ships off the Falklands (MoD)

As early as 1 April, five naval Wessex 5 transport helicopters had been prepared for airlift from RNAS Yeovilton to Ascension, two for embarkation in RFA Tidespring and the others for local stores delivery duties. The first pair were flown out on 4 April in a civilian Short Belfast freighter of the Stansted-based TAC HeavyLift Ltd (which had bought the RAF’s inventory of this aircraft when the type had been retired on grounds of economy in 1976) and reassembled by the Naval Aircraft Servicing Unit, Ascension, otherwise known as Naval Party 1222. These aircraft were operational by the time that the next two were delivered, on 6 April.

The ‘Wessi’ had been preceded, on the 3rd, by three Lynxes which arrived complete with air and ground crews and a full range of stores, by courtesy of the RAF Hercules of the Lyneham Transport Wing. The Lynxes, manned by the 815 Squadron Trials Flight and the Flights of HMS Newcastle and Minerva, were modified to fire the Sea Skua air-to-surface missile – which had not yet been formally accepted into service – and were intended for RFA Fort Austin. They embarked on 6 April, so that when the otherwise unarmed stores ship left Ascension to support the Endurance she had a powerful, if untried, defensive capability.

The first surface ship to leave the United Kingdom for the South Atlantic sailed quietly from Portland on Sunday, 4 April. The Royal Maritime Auxiliary Service ocean-going tug Typhoon was certainly not the most glamorous unit to deploy but she was an essential part of the supporting forces, as she would demonstrate at South Georgia. It was soon appreciated that more tugs would be needed and three United Towing Company vessels were requisitioned – the Irishman, Salvageman and Yorkshireman.

5 May: The Hermes sails from Portsmouth half an hour after the Invincible, her hangar so crammed with stores and ammunition that most of her aircraft have to be parked on deck. The last (in Royal Navy service) of a line of highly-successful ‘Fleet carriers’, this old ship fully demonstrated the soundness of an earlier British design philosophy (MoD)

The first ship to sail from the United Kingdom, and one of the last to return (on 24 September), was the RMAS tug Typhoon, here seen in South Georgia waters (MoD)

Under the full glare of publicity, the aircraft carriers sailed on Monday, 5 April, Invincible passing vast crowds watching from the walls of Portsmouth and on Southsea seafront half an hour ahead of the Hermes. All concerned in their despatch in such a short time deserved the applause, but particular credit must go to the Dockyard staff at Portsmouth: few of those waving goodbye to the ships or watching the drama on television could have imagined, for example, that only 24 hours earlier the Hermes’ island was festooned with scaffolding or that storing of both ships had continued until the last gangway had been moved away. The eleven Sea Harriers and eighteen Sea Kings on Hermes’ deck were there not only for the usual ceremonial purposes but also to permit the hangar to be used as a sorting office for the vast quantity of extra stores, which even included 200 tons of ammunition for the Marines. The Invincible had fewer of her aircraft ranged, but among her deck cargo were anonymous crates which contained extra Sea Dart missiles, for herself and for the three Type 42 destroyers, 2,000 miles closer to Ascension.

Four hours before the carriers began to get under way at Portsmouth, the Type 21 frigates Alacrity and Antelope left Devonport and during the day met the LSLs Sir Geraint and Sir Galahad from the same port and Sir Lancelot and Sir Percivale from the Solent. The LSLs were carrying up to 400 Marines, Army, Naval and RAF personnel apiece, as well as the stores, weapons and ammunition, and the 3 Commando Brigade Air Squadron, with its three Scout and nine Gazelle helicopters. Two RFA tankers left on the 5th, the Olmeda from Devonport to accompany the carriers and the Pearleaf from Portsmouth to join the LSL group. The former had embarked two more anti-submarine Sea Kings, of 824 Flight, embarked and aboard the ‘AEFS’ (Ammunition, Explosives, Food and Stores ship) RFA Resource was a Wessex 5 for ‘Vertrep’ duties – vertical replenishment of stores. The Resource had been at Rosyth when the Fleet had been brought to short notice and had worked round the clock to load with a full cargo of war supplies, picking up the last items at Portland shortly before midnight on the 5th.

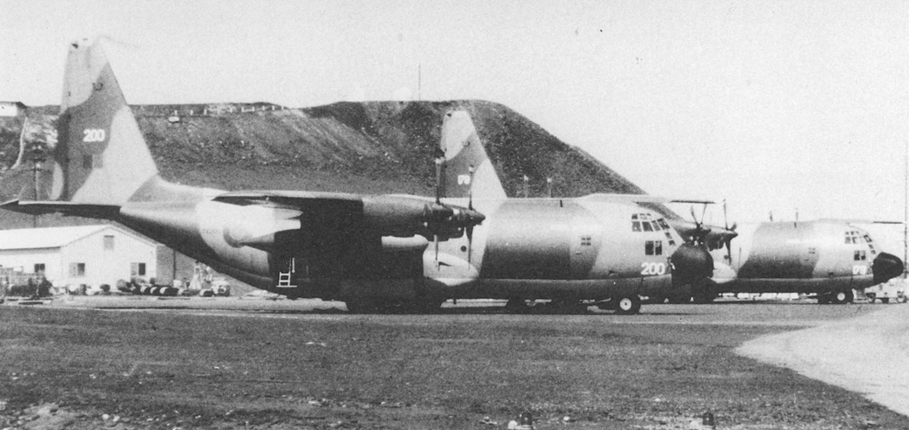

6 April: the Landing Ship (Logistic) Sir Galahad leaves Devonport for the last time, her midships deck loaded with stores and vehicles and with three Gazelle helicopters of 3 Commando Brigade Air Squadron on her flight deck. Devonport was the last UK port of call for four of the ships lost ‘down South’ – the Antelope, which sailed with the Sir Galahad, the Ardent, which left on 19 April, and the Atlantic Conveyor (MoD)

HMS Broadsword and Yarmouth left Gibraltar on the same day, heading east for the Suez Canal. Some twelve hours after their departure it was decided that their presence was more urgently required in the south and they were ordered to return to Gibraltar and prepare for deployment to the South Atlantic. Of the eleven destroyers and frigates now at sea for ‘Corporate’, only the Yarmouth, the oldest of all, would come through unscathed.

The last sailings of what may be regarded as the ‘first wave’ were on 6 and 7 April. The Fearless, having put ashore her ‘young gentlemen’ to return to Dartmouth as late as the 5th, sailed from Portsmouth on the next day, carrying vehicles and heavy equipment for 3 Commando Brigade, three more Scout helicopters of the Brigade Air Squadron and another three Sea King 4s of 846 Squadron. Commodore Clapp and his staff were aboard when she sailed and Brigadier Thompson and his staff joined by helicopter off Portland. On the next day the Stromness left Portsmouth just after dark. Although her sailing was twenty-four hours after the time called for on 3 April, her departure, fully stored and with military rations for 7,500 men for a month and 358 Royal Marines aboard, was a magnificent achievement, bearing in mind that on 2 April she was in dock, completely destored prior to disposal and with only a care and maintenance crew on board.

The departure of the United Kingdom component of the task force marked only a change of task, not tempo, as far as the Dockyards and Naval Stores and Transport organization were concerned. Rather more time was available to prepare the next small group of warships and RFAs to leave, but there was a steady stream of ‘STUFT’ to equip with replenishment gear, radio gear compatible with that in the Fleet, commercial satellite communications equipment, additional fuel tanks, fresh water production plants, extra accommodation and facilities for operating helicopters. Portsmouth Dockyard led the way on the conversions, with as many as five merchant ships at a time being fitted out and with at least one in hand from 8 April until 21 May; altogether, twenty-five tankers, freighters, tugs, and short-sea ferries were modified and, in the case of the tankers, loaded, at this one yard up to mid-June. This was, of course, in addition to the normal warship work, which now involved the incorporation of new or modified equipment shown to be necessary as the results of experience ‘down south’ as well as routine maintenance. The Dockyard workshops prefabricated most of the steelwork for the various installations, which were designed by the Navy’s own architects, the Royal Corps of Naval Constructors, whose centenary year this was.

Devonport Dockyard undertook fewer STUFT conversions but some of these were among the most well-known ships as they included the four aircraft transports, beginning with the ill-fated Atlantic Conveyor and continuing with the Atlantic Causeway, Contender Bezant and Astronomer. Much of the dockyard’s additional work consisted of accelerated turn-rounds for the frigates which would be required for later ‘Corporate’ deployment. HMS Minerva entered Plymouth Sound on 2 April flying her paying-off pennant in anticipation of a long refit but left five weeks later after a comprehensive maintenance period and the Battleaxe’s programmed fifteen-week docking period was cut to ten weeks. The departure of so many ships for operations outside the NATO area meant that those that were left had to have a higher rate of availability, which led to further work for Devonport as some frigates were run on beyond intended maintenance periods.

Making up for the shortage of ships fell largely to Chatham Dockyard’s lot. Sentenced to closure by the 1981 Review, Chatham was the home of the ‘Standby Squadron’, the very small reserve of frigates awaiting disposal. On 13 April the Falmouth (a sister-ship of the Yarmouth) was ordered to be brought forward off the Sales List and was commissioned just nine days later. Four more frigates were surveyed but such was the shortage of naval personnel in some categories that it was not until 26 May that the decision was made to bring forward HMS Berwick, Zulu, Tartar and Gurkha, the first two to be prepared for service by Chatham and the second pair at Rosyth. Although no STUFT conversions were undertaken at Chatham, the workshops joined the prefabrication programme, sending metalwork to Portsmouth and Devonport.

In normal times the Royal Navy’s mine countermeasures ships are based on the Forth and when it was decided that a number of trawlers should be taken up as minesweepers, they were taken in hand at Rosyth Dockyard for the installation of communications gear and other essential equipment. Commissioned with all-naval crews from three ‘Ton’-class minesweepers, Farnella, Junella, Cordelia and Northella, later joined by the Pict, were the only STUFT to wear the White Ensign and operated as the 11th Mine Counter Measures Squadron. Two North Sea oil industry support vessels, the Wimpey Seahorse and British Enterprise III, were modified at Rosyth, the former as a mooring vessel for laying the mooring buoys and cables which would be needed at South Georgia and the Falklands themselves, and the latter as a ‘despatch vessel’ to ply between Ascension and the forward areas with passengers and urgent stores too heavy or awkward to be air-dropped. Rosyth also despatched the two Offshore Patrol Vessels HMS Leeds Castle and Dumbarton Castle for use as despatch vessels and the Post Office cable ship Iris was converted for the same purpose at Devonport.

The ‘Ellas’, as the five auxiliary minesweepers became known, went from Rosyth to Portland to be fitted with their replenishment gear and the deck fittings for the sweeping equipment. Portland’s main task was that of working-up warships and auxiliaries, but a Fleet Maintenance Group was in attendance for running repairs. The FMG now became heavily involved in the material preparation of not only warships but also RFAs and STUFT, completing the fitting-out of the new RFA tanker Bayleaf, modifying the STUFT tanker British Esk for the supply of Dieso fuel and installing a Service radio and power supplies in her swimming pool and building and testing fresh water plant for the two ‘Castles’, among other tasks, most of which were more appropriate to a Dockyard than to a ‘Naval Base’.

Portland continued to be responsible for working ships up as fighting units and evaluating new tactics at sea. Flag Officer Sea Training’s staff provided detachments to accompany southbound ships as far as Ascension, the first such team being made up of damage control experts who left with HMS Fearless. After the departure of the first wave virtually all warships spent a few days at Portland, exercising every aspect of their organizations – ‘sea riders’ even flew out to Gibraltar to work up HMS Ambuscade on passage to Ascension, so that she might not miss the gruelling but necessary experience. Particular attention was devoted to air defence exercises, the opposition being provided by the Fleet Requirements and Air Direction Unit, a civilian-manned ‘squadron’ based at Yeovilton. Using Canberras and Hunters, FRADU simulated Super Etendard/Exocet attacks as well as more conventional massed low-level attacks in the Portland exercise areas and also for the benefit of the Surface Weapons Establishments, which were busy devising improvements to the various defensive missile systems throughout the campaign. The ‘resident work-up tanker’ for most of the period was RFA Grey Rover and she too was fully occupied, for many of the chartered merchant ships conducted their replenishment trials and training with her off Portland.

The work of the Dockyards and the uniformed maintenance organization was supplemented by shipbuilding industry contractors, working to naval Constructors’ designs and with Dockyard supervision. The first conversions were, in fact, those of the liner Canberra and the ferry Elk, carried out at Southampton by Vosper Ship Repairers; the Canberra arrived from a cruise on 7 April (the day after the Elk had been put in hand) and sailed on the 9th with 40 and 42 RM Commandos and 3 Para on board, amid emotional scenes.* In the intervening two days two helicopter decks had been added, at the expense of upper deck fittings and bulwarks, and the ‘standard’ replenishment and communications kits added to turn her into a ‘Landing Platform Luxury (Large)’. Vospers also converted the second LPL(L) – the Queen Elizabeth 2, the water tanker Fort Toronto, the Europic Ferry and, towards the end of the campaign, the large passenger ferry Rangatira. Elsewhere, the Ro-Ro ferry Norland was partly modified at Hull, where industrial action delayed her sailing by twenty-four hours on 20 April (the only such blot on an otherwise clean record of co-operation between the Navy Department, employers and the unions), and had her helicopter deck added at Portsmouth.

Like Chatham, Gibraltar Dockyard was also promised with closure. Its value was underlined at the very outset of the operation by its support to Rear Admiral Woodward’s force of destroyers and frigates and the three RFAs, Fort Austin, Appleleaf and Tidespring, and then the storing of Broadsword and Yarmouth, which sailed south on 8 April. This depleted the already low stocks to such an extent that the Type 21 frigate Ambuscade carried a cargo of extra ammunition when she left Devonport on 9 April for Gibraltar, where she was to be stationed as Guardship. Four days later the RMAS ammunition transport Throsk, which had been in reserve at the beginning of April, left with a cargo of medical and aviation stores, a replenishment ‘kit’ and other gear. This load was intended for a specific ship, the P&O liner Uganda which, when taken up on 10 April, was on an educational cruise in the Mediterranean. The school parties were put ashore in Naples and the ship proceeded to Gibraltar, where she was converted for use as a hospital ship, with full surgical facilities and ward accommodation for 300 patients, tended by naval medical personnel who included Queen Alexandra’s Royal Naval Nursing Service sisters. A helicopter deck capable of operating a Sea King was built on aft, for receiving casualties, necessitating very heavy reinforcement of the deck below and using up most of the dockyard’s stock of steel plate and beams.

The Uganda was declared to the Red Cross as a hospital ship and was marked with the appropriate markings on her repainted white hull. In keeping with her strictly non-combatant role, she was not fitted with cryptographic machines nor did she carry ciphers or codes. To support the Uganda by evacuating casualties from the combat area to her operating area, the three survey ships HMS Hydra, Hecla and Herald were fitted out as ‘Ambulance Ships’, the Hecla at Gibraltar and the others at Ports-mouth. Like the Uganda, they bore red crosses on a white hull and were declared to the International Committee of the Red Cross. Their Wasp helicopters were also painted with red crosses and exchanged their red flashing anti-collision lights for blue ‘ambulance’ lights. Thus equipped, the four Red Cross vessels sailed, the Uganda from Gibraltar on 21 April, preceded by HMS Hecla on the 20th and the other two ‘H’s from Portsmouth on the 24th.

No further hospital ship declarations were made by the Ministry of Defence, but the presence of a special surgical team in the Canberra was reported in the Press, certain sections of which seem to have believed that when she disembarked her troops she would serve as a hospital ship. No such misunderstanding could be entertained for the Hermes and Fearless, both of which had additional surgical teams embarked. One result of this departure of large numbers of medical personnel was the suspension of professional nursing training at the RN Hospitals at Haslar and Stone-house as the instructing staff either went to sea or took the places of the ward staff who had done so.

The welfare of the families of the men overseas is at any time a major concern of the Navy’s shore organization, but the arrangements were now enlarged to deal with the vastly greater numbers. Those left behind in the various establishments did their best to sustain the morale of anxious wives by organizing social activities and keeping families informed as much as was possible, a task which grew more difficult as the numbers of ships involved and the casualties grew.

To ensure that, in the worst case, families learned of casualties first and that care was immediately available, the Naval Casualty Reporting System was set up early in April. Under the administration of the Commander-in-Chief, Naval Home Command, Admiral Sir James Eberle, reporting cells were manned around the clock and individual shore establishments throughout the country were given the responsibility for the unhappy task of notifying the next-of-kin of the casualties; this could be done quickly when the family lived in married quarters, but up to twenty-four hours could be spent tracing others who could not be found immediately at the expected address. The system was intended to avoid unnecessary distress, usually caused by outside interference, almost invariably involving the media.

It has been said, with some justification, that the Royal Navy lacked rapport with the media, the Army’s good relations with the Press in Northern Ireland being held up as an example of what can be achieved. At least some of this misunderstanding, which took the form of, at best, mistrust on the Navy’s part, was due to the nature of the Navy’s work, the most impressive area of which is found well away from land or international airport terminals, so that achievement is reported late or not at all, except through Ministry of Defence Press Releases. The few newspapers which employ capable defence correspondents are trusted to a greater extent, but they are a tiny remnant of the informed and responsible community which reported on naval affairs up to the First World War – before the Official Secrets Acts, which were intended originally to discourage spies but now have the effect of suppressing politically undesirable discussion.

It was widely supposed that the Navy intended to take no journalists other than those employed by the Defence Public Relations organization and that those who were embarked immediately before the carriers sailed were included on the Prime Minister’s insistence. Be that as it may, sixteen writers, two photographers, two radio reporters and three television reporters supported by four technicians did go to sea, eleven with the carrier group and sixteen with the amphibious ships. A very few of this number were experienced war correspondents who had an inkling of what to expect and went prepared for the conditions.

* The old and respected term ‘Admiralty’ lapsed on 1 April, 1964, when the Royal Navy’s operational and administrative headquarters ceased to be an independent department of state and became one of the constituent Departments of the Ministry of Defence.

* ‘Commodore’ in the Royal Navy is a title and not a rank and denotes an appointment held by a senior Captain. Commodore Clapp – ‘COMAW’ – was one of eight such officers in 1982 and the only one with a sea-going job.

* Legend has it that the Marines persuaded the Paras to occupy the lower accommodation decks by telling them that less ship movement would be felt, compared with on the more luxurious accommodation on the decks above, which the wily Commandos occupied.