Chapter Four

Aftermath

The end of the fighting was marked by a change for the worse in the weather. After a week of clear but cold conditions, interspersed with occasional snow showers, the snow fell steadily and the wind drove it hard. The Plymouth and Yarmouth, returning to the Battle Group after a quiet night in Berkeley Sound, reported the worst weather that they had experienced since leaving for the South Atlantic, with a Force 10 storm and confused seas which reduced their speed to 11 knots. In the early hours of 15 June the Battle Group had to abandon replenishment and then withdraw the Sea King 5s from the anti-submarine screen – the first time for over a month since this had been necessary.

The Glamorgan had ‘borrowed’ one of the Tidespring’s Wessex 5s and this aircraft was severely damaged on deck. The destroyer’s hangar was open to the elements after the Exocet explosion. Outside the TEZ the RAF maintenance personnel of No 18 Squadron aboard the Europic Ferry were preparing the replacement Chinooks brought south by the Contender Bezant, stripping off the weatherproof covering and fitting rotor blades on board the aircraft transport before flying the big helicopters across to the ferry for final checks prior to sending them inshore, via the Hermes. The first such replacement had been despatched on 14 June, arriving in East Falkland a couple of hours after the ceasefire and a second Chinook landed on the Europic Ferry that evening. It was to remain for two days, 15 tons of topweight on the heavily-rolling North Sea ferry, whose officers more than once considered jettisoning it. The helicopter not only survived, it escaped damage and was flown off on 16th, by which time the weather had moderated.

The surrender of the Argentine forces in West Falkland was the main concern of Commodore Clapp’s ships on the 15th. Captain White took the Avenger to Fox Bay, where she arrived shortly after midnight, but the Cardiff did not set off for Port Howard, escorting three of the Intrepid’s LCUs, until dawn. Another LCU went around to Pebble Island. Two intact regiments surrendered – 1, 748 troops who had been engaged only by ships’ gunfire and aircraft, as well as the 155 men of a marine company occupying Pebble Island. These prisoners were ferried to San Carlos Water, where they were joined by General Menendez and the senior members of his staff, who were transferred to the Fearless by helicopter.

The British forces were now looking after 10, 254 prisoners, over 8, 000 of whom were moved from the Port Stanley area to the airport peninsula, where they had to improvise shelter from the elements. The state of the 6, 000 conscript soldiers, the majority of whom were in poor physical condition due to the neglect of their officers and NCOs, greatly concerned General Moore, whose staff did their best to alleviate the misery by tracing and making available the Argentine stocks of food and clothing which their own quartermasters had been unable to devise means of distributing. The risk of mass deaths due to exposure or disease was very real but could not be averted until the Junta agreed to a plan for their evacuation.

A start had been made on processing the prisoners on the first day of full British control. The Canberra had returned to San Carlos Water at dawn and she embarked 1, 121 Argentinians before dark. Each prisoner was properly documented as he came on board and then identified, using P&O baggage labels. The cabin accommodation on B Deck and below was allocated to them, while the 100 Welsh Guardsmen and RAF personnel detailed as guards lived on A Deck. Argentine wounded, mainly from the battle of the 13/14th, were transferred to the Bahia Paraiso, which joined the Uganda in the Falkland Sound during the day.

At 8.15am on 16 June the Canberra left San Carlos Water, escorted by the Andromeda and the Cardiff, and five hours later was off Port William. The position of the minefield laid in mid-April off Cape Pembroke had been given to the Royal Navy and was already being swept by the ‘Ellas’, but the Canberra was routed around it, preceded by the Andromeda, which was thus the first British ship to enter Port William. The liner anchored outside the Port Stanley narrows, protected by the Sea Wolf-fitted frigate and with a Sea Harrier CAP overhead. A company of 3 Para joined as additional guards and then the embarkation of prisoners from the airfield began, using the Forrest and three of the Canberra’s own motor boats on a shuttle service throughout the night.

Captain David Pentreath was ordered on the 15th to assume the duties of ‘Queen’s Harbour Master’ at Port Stanley and it was appropriate that HMS Plymouth should be the first ship to enter the harbour, early on 17 June, followed by the hard-working RFA Sir Percivale, whose Master, Captain Pitt, promptly sent a signal to inform the Navy that the Blue Ensign was once again flying off Port Stanley. The LSL was a welcome arrival, for she was used as a Rest and Recreation vessel for the cold, tired and dirty Commandos and Paras, who were able to enjoy ‘the indescribable bliss of a hot shower, followed by a meal prepared by someone else, and a few beers’.

Port William rapidly became very full. The Canberra and Andromeda were joined by the Fearless, Minerva and Sir Bedivere from San Carlos, while the Brilliant brought in the Contender Bezant, Europic Ferry, Tor Caledonia and St Edmund from outside the ‘Trala’. The last two ships carried, respectively, the equipment and personnel of another Army Rapier battery and a mobile RAF radar station for the defence of Port Stanley. The naval helicopters were flying as hard as ever, even though the land fighting was over, ferrying men and material between the various base areas and the ships and to support them the Atlantic Causeway anchored in Port William. The Nordic Ferry, RFA Resource and Fort Toronto also came in from the ‘Trala’, the first two with stores and provisions and the last bringing her fresh water. The Port Stanley water supply had been interrupted by damage to the pumping station – even when this was patched up by the Royal Engineers it would be quite insufficient for the vastly-increased population. The much-travelled tug Typhoon made up the group.

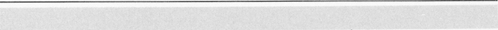

HMS Active passes STUFT in Port William after the surrender – the Lycaon, Geestport and Astronomer, with RFA Olna at extreme right (MoD)

Admiral Woodward’s Battle Group maintained vigilance. Although it was believed that the Junta would not order an attack on the Port Stanley area as long as the prisoners were still present, there was no sign that the Argentinians accepted that the war was over. The SHARs and Sea Kings maintained their defensive patrols and the radar warning cover was extended to the west by stationing a frigate off West Falkland, the first such picket being HMS Minerva. A STOVL strip was laid on Stanley racecourse and No 1 Squadron’s GR3s were disembarked, while up to four SHARs were sent ashore every day to spend daylight at readiness, occasionally scrambling when the picket ship detected Argentine aircraft probing the edge of the TEZ.

The Canberra completed loading prisoners on 17 June, by which time she had 4, 167 on board. Thanks to the intercession of the Red Cross and the efforts of the Swiss and Brazilian Governments, the Junta agreed to the return of the Argentinians aboard the Canberra, which was given a safe-conduct to proceed unescorted to Puerto Madryn, 650 miles to the north-north-west of Port Stanley. The liner sailed from Port William during the morning of the 18th, as news of the resignation of General Galtieri as Commander-in-Chief and President of Argentina was received. The Norland reached Port William later on the same day and began to load another 2, 047 prisoners. An Argentine oil rig support ship, the Yehuin, assisted in ferrying these men out. Found by the Plymouth alongside the Falkland Islands Company’s jetty, she had been adopted as a suburb and renamed ‘HMS Oggie’.* Another Argentine vessel, the Coastguard patrol vessel Isla Malvinas, was also found in seaworthy condition. This name was quite unacceptable and, manned by a party from HMS Cardiff, she became ‘HMS Tiger Bay’. The other prize in Falklands waters was the Bahia Buen Suceso. Abandoned by her crew in Fox Bay, with minor hull damage but defective machinery, the Avenger discovered her aground, infested with rats and still loaded with a large quantity of ammunition and explosives.

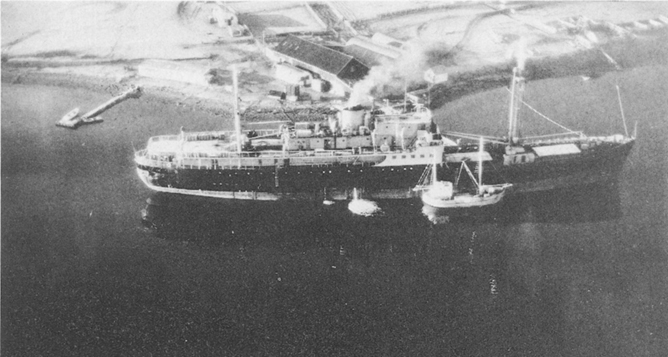

The ex-Argentine oil-rig support vessel Yehuin, used for inter-island supply from an early stage of the occupation, escaped attack and, found intact at Port Stanley, was pressed into British service for harbour tasks (MoD)

The Canberra entered Argentine territorial waters at 10.00am on 19 June and was escorted to Puerto Madryn by the Type 42 Santissima Trinidad and the ex-American Comodoro Py. The Canberra secured alongside a long ore pier, on which a queue of lorries and buses was drawn up to transport the returning prisoners and the process of negotiating and then unloading began. Three hours after the first man stepped ashore, to be greeted by a VIP reception party, the liner slipped from the jetty and began a 24-knot run back to the Falklands.

The Norland brought the next contingent to Puerto Madryn two days later and the balance of the prisoners were carried home by the Bahia Paraiso and the Almirante Irizar. The use of the latter was appropriate as she had, on 2 April, brought some of the earliest unwanted arrivals.

While the British forces had been establishing themselves in Port Stanley and the Argentine prisoners were being taken home, the final steps to eject invaders from British territory were being taken. South Thule, 450 miles to the south-east of South Georgia, lay at the further end of the South Sandwich Islands, barely thirty miles north of the internationally-agreed demilitarized Antarctic, which began at 60° South. The Argentine Navy and Air Force had illegally established a weather reporting station on the island in 1976, manned by up to forty Servicemen. Diplomatic requests to remove them had had no effect and now they were to be taken away by force, if need be.

The Yarmouth and Olmeda were detached from the Battle Group during the forenoon of 15 June and proceeded to South Georgia, where two rifle troops of Mike Company, 42 Commando, were to be embarked as the assault force. The Reconnaissance Sections and a mortar crew went aboard the Endurance, which borrowed a Wessex 5 from the RFA Regent, which was storing from the provisions ships Saxonia and Geestport at Stromness. The frigate and tanker arrived at Grytviken on 17 June, shortly before the ice patrol ship and the tug Salvageman sailed, and ferried the eighty-one Royal Marines on board by helicopter, using the Olmeda’s Sea Kings. Captain Nick Barker’s Task Unit was thus made up of representatives of all the main elements of the naval contribution to Operation ‘Corporate’ – a warship, an RFA, a merchant vessel, no fewer than six helicopters and Royal Marine commandos, plus his own HMS Endurance.

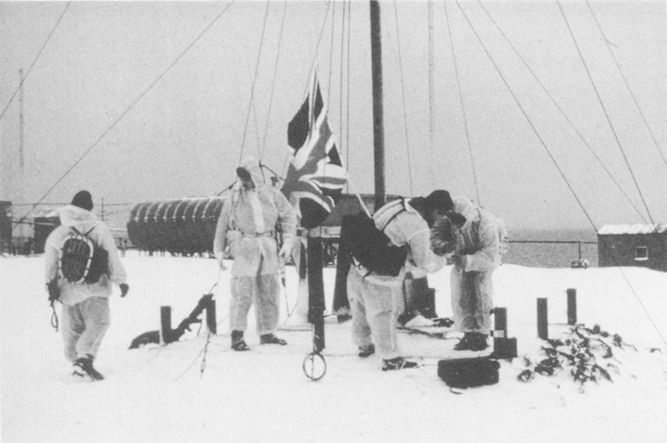

The Endurance’s Wasps landed ten Marines of the Recce Sections behind the weather station on 19 June. Realizing that this insertion could not have passed unnoticed, further flights were made to simulate landings here and there, to confuse the Argentinians as to the intentions and strength of the troops ashore. The Yarmouth and Olmeda joined the Endurance and Salvageman off South Thule at about midnight on the 19/20th and Commander Morton was ordered to proceed inshore to support a landing. At dawn on 20 June the Marines ashore were ordered to advance down towards the station, while the Yarmouth was to conduct a gunfire demonstration at 9.30am. The sight of the advancing Marines was sufficient for the Argentinians. They emerged from their huts to surrender six minutes before the Yarmouth was due to open fire.

Only ten men had been occupying the base, the rest having been taken away early in the campaign. The weapons had been dumped as soon as the first wireless invitation to surrender had been received, resistance by such a small and isolated group being clearly useless. The prisoners were flown off to the Endurance, which remained behind with the Salvageman after the departure of the frigate and tanker with the Marines, to tidy up the inevitable mess left by the Argentinians and to secure the building against the Antarctic weather. Captain Barker returned to South Georgia on 24 June.

Last Act: Royal Marines of ‘M’ Company, 42 Commando, prepare to raise the Union Jack and the White Ensign over South Thule on 20 June, after their unopposed repossession of the island (MoD)

The interim President of Argentina, General Bignone, was sufficiently secure in office by 21 June to be able to announce that the ceasefire of 14 June would be observed by the forces on the mainland, but that no full peace was possible until the Falklands had been ‘restored’ to Argentina. The British Government welcomed the acceptance of the ceasefire but decided that a force adequate to repel any further adventure should be retained in the area.

The Glamorgan, with her Seaslug system operational thanks to the attentions of the Stena Seaspread (by now established at San Carlos), and the Plymouth began their passage home on the 21st, the day that the Glasgow arrived to a warm welcome at Portsmouth. Four days later the Alacrity returned to Devonport and the Canberra sailed for the last time from Port William, carrying the Royal Marines of 3 Commando Brigade and their magnificent supporting Army formations. The Norland and Europic Ferry left on the same day with the two Parachute Regiment battalions, who would fly home from Ascension Island. Most of the 183 Marine and Army personnel wounded while serving with the brigade had already left, but sixty-eight officers and men were left buried at Ajax Bay, Teal Inlet and Darwin.

10 July: her starboard side showing no indication of the damage caused by the Exocet hit, the Glamorgan passes Haslar Creek on her way up Portsmouth Harbour (MoD)

14 July: a quiet reception for the Intrepid as she approaches the old fort guarding the entrance to Portsmouth on a misty morning – her great welcome had been on the previous day, when she had disembarked her Marines and landing craft at Plymouth (MoD)

3, 000 miles to the north-east of the Falklands the Invincible was conducting a self-maintenance period at sea, screened by the Andromeda. The two ships had detached from the Battle Group late on 18 June and reached 23° South latitude five days later. There she began a main engine change, a task which had never been attempted at sea before but which was accomplished with complete success in six days. On 1 July her ship’s company went back once more to Defence Watches as she passed the latitude of the River Plate. The Hermes had carried the weight of air defence during the Invincible’s absence. With the return of the latter she could now be detached, to return on 21 July to Portsmouth.

The Task Force bade farewell to another of its stalwarts, and probably one of the best-known, on 25 June. The Sir Galahad, which had lain off Fitzroy Cove since she had been hit on 8 June, was towed out to sea and scuttled by a torpedo fired by HMS Onyx, to the south-west of Port Stanley. Not all the casualties of the attack had been recovered for burial ashore and, like the wrecks of all the ships of both sides sunk during the campaign, hers is a war grave. The Sir Tristram was refloated and towed from Fitzroy Cove to Port Stanley, where she was moored as an accommodation hulk, her tank deck providing shelter for men and stores. In 1984 she was brought back to Britain as deck cargo on a salvage barge and taken in hand for reconstruction.

The submarine Santa Ye, aground off King Edward Point, South Georgia, was raised to clear the jetty and beached out of the way. Not until early 1985 was it decided that she should be refloated for the last time, to be towed out to sea by tugs and scuttled in deep water off Cum-berland Bay. A much earlier disposal was the Bahia Buen Suceso. She was towed from Fox Bay to San Carlos Water in late June and her cargo of ordnance was unloaded during the next few weeks. No further use being seen for her, she was towed to the south of the Falkland Sound and, on Trafalgar Day, 1982, was used as a target for every type of gun, given a coup de grace by the Onyx and depth-charged as she went down.

16 May: the Bahia Buen Suceso, a naval auxiliary, which had landed the civilian workers at Leith Harbour, South Georgia, two months earlier, was strafed at Fox Bay by Hermes’ Sea Harriers and left immobilised until the surrender (MoD)

Admiral Woodward was relieved on 1 July by Rear Admiral Derek Reffell, who had transferred to HMS Bristol from the Iris, which had brought him out to the TEZ from Ascension. It had been intended that Port Stanley airfield would be ready to permit RAF Phantom fighters to assume the SHARs’ air defence task from mid-July, but the necessary airfield matting, shipped in by the STUFT Strathewe, did not arrive until then. The Invincible therefore stayed on, sighting land for the first time in ninety-eight days (on 12 July), transiting the Falkland Sound (on 28th) and anchoring in Berkeley Sound for a celebratory dinner, as her predecessor had done in December, 1914. The TEZ had been reduced to a radius of 150 miles on 22 July and its title changed to ‘Falkland Islands Protection Zone’.

On 27 August the new HMS Illustrious arrived. A near-identical sister of the Invincible, her completion had been advanced ahead of the original building programme by months, thanks to the efforts made by her builders, the Tyneside yard of Swan Hunters, and the Royal Dockyards. Her air group consisted of ten Sea Harriers of the re-formed 809 Squadron, eight Sea King anti-submarine helicopters of 824 Squadron and two Sea Kings modified to carry a Thorn-EMI Searchwater radar in a massive pivoting hemisphere carried on the starboard side of the cabin. This combination, which had been developed in just eleven weeks, provided the much-needed Airborne Early Warning capability which had been so sorely missed during the campaign. For her own last-ditch self-defence against missiles such as Exocet, the Illustrious was armed with two Phalanx systems purchased from the United States Navy. Each mounting consisted of a six-barrelled 20mm Gatling-type gun, firing 4, 000 high-density rounds per minute, with a computer adjusting the point of aim by comparing the relative positions of the target and the stream of shot.

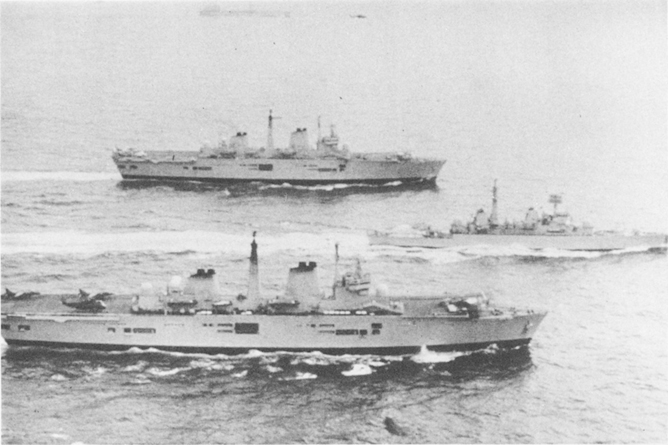

The new Illustrious (furthest from the camera), completed months ahead of schedule, arrives on 27 August to relieve the Invincible as the carrier on station and to take over from the Bristol, flying the flag of Rear Admiral Derek Reffell, as flagship of the squadron off the Falklands (MoD)

The Illustrious left the area on 21 October, four days after the arrival of the first Phantoms at Port Stanley. All the warships which had seen service in the TEZ between 1 May and 14 June, with the exception of the Onyx, had returned to the United Kingdom and some were on their way out again for a second tour. Many of the merchant ships were still serving on charter in the South Atlantic, providing fuel, ferrying passengers and freight between the islands and Ascension or providing specialist services, like the Stena Inspector, which had taken over from the Seaspread. The last RFA to return from the invasion under her own power was the Sir Bedivere, which reached Marchwood in November, 1982, with her sad cargo of the bodies of those men whose relatives wished them to be interred at home.

28 July: the end of a successful deployment for HMS Exeter as she enters Portsmouth Harbour, escorted by naval and RMAS craft and, overhead, an RAF Phantom (MoD)

More festive had been the return of the other ships, the Norland to Hull – few merchant ships had been placed in greater danger or had seen more varied service – the Stromness to Portsmouth, to resume the run-down prior to sale to the US Government, and all the other auxiliaries to their home ports, few to any great fanfare other than by those who knew the ships, their men and what they had accomplished.

The warships, too, had their own special welcomes. HMS Arrow was greeted by the RAF’s ‘Red Arrows’ formation team, trailing red, white and blue smoke, as she passed up Plymouth Sound on ’ July. At Rosyth, Chief Yeoman Ron Doakes, egged on by his mess-mates, had to repeat the story of his mangled bicycle to Radio Forth when the Plymouth returned on 14 July, her battered funnel casing bearing testimony to her narrow escape.

14 July: with her hull number repainted and once more wearing the black funnel-band which identifies her as the Leader of the 6th Frigate Squadron, the Plymouth passes North Queensferry on her way to a warm welcome at her base port, Rosyth (MoD)

The national experience, with live television coverage, was, however, reserved for the ‘big three’. Few who watched the return of the Canberra to Southampton on 11 July will forget the moving experience as ‘The Great White Whale’, with rust streaks around almost every hatch and opening in her sides, came alongside the crowded quay, her decks thronged with the men of 3 Commando Brigade, while Naval Party 1710 lined the edge of the forward flight deck, where the Royal Marine Band was playing, inaudibly.

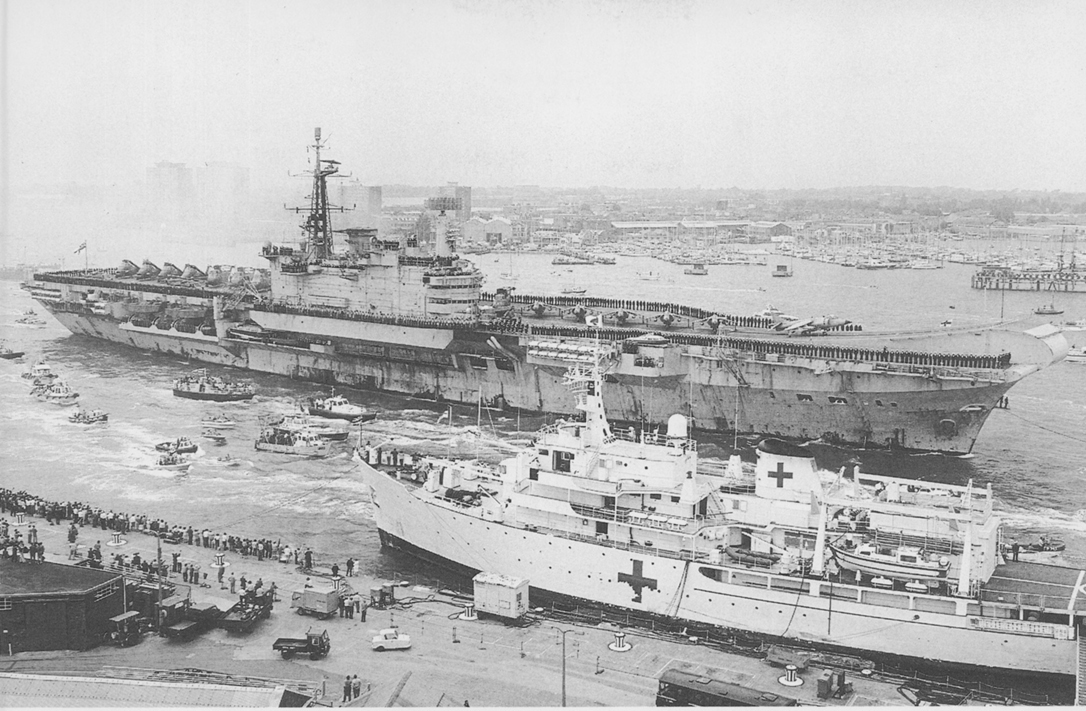

For the Hermes, returning on a weekday, there was again live TV cover, as there was for the Invincible when she reached Portsmouth with the Bristol on 17 September. With their homecoming, the man in the street felt that the war was indeed over.

21 July: the Hermes comes home, her aircraft and ship’s company lined up for the full ‘Procedure Alfa’ entry into harbour. In the foreground is the Herald, which had arrived earlier on the same day – the first of the ‘Ambulance Ferries’ to come home (MoD)

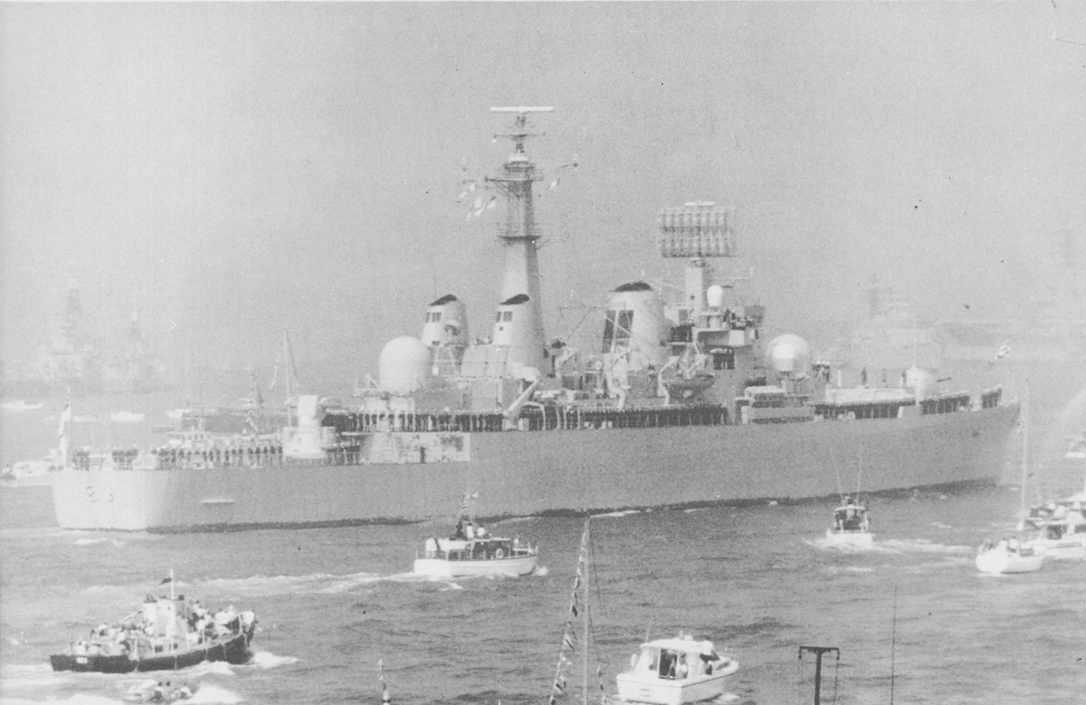

17 September: the last ships come home – Bristol, with her escort of small craft in the foreground and ‘yesterday’s Navy’ in the background, passes the Portsmouth Dockyard waterfront (MoD)

And what it cost – the Type 21 Memorial on Campito Hill, overlooking the last resting place of the Antelope off Ajax Bay and, in the other direction, the Ardent, off the North West Islands, in the Falkland Sound (MoD)

* The west Country name, used universally in the Navy, for a Cornish Pasty.