Two

“I WILL NEVER USE THE WORD ‘UNACCEPTABLE’ AGAIN”

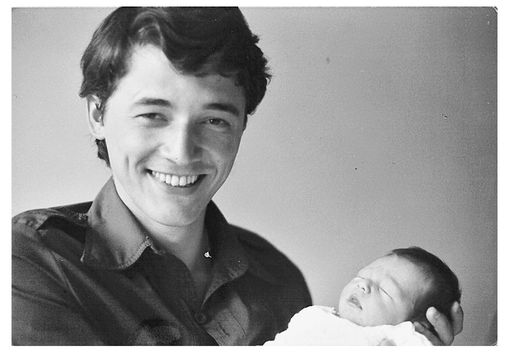

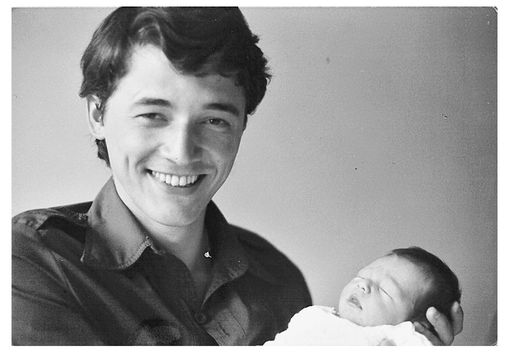

Vieira de Mello holding his six-day-old son Laurent, June 8, 1978.

It was in Lebanon that Vieira de Mello first encountered terrorism. Although he knew that many promising careers were torpedoed in the Middle East, for him the region’s most damning qualities—its contested geography, political turmoil, and religious extremism—were what enticed him. By 1981 he had been performing purely humanitarian tasks at UNHCR for twelve years, and he felt his learning curve had leveled off. When he heard from a colleague that a UN job had opened up in Lebanon, which he judged the most challenging of all UN assignments, he submitted his résumé and was selected to become political adviser to the commander of peacekeeping forces in the UN Interim Force in Lebanon (UNIFIL). Just thirty-three years old, he took leave of UNHCR, his home agency, with strong convictions about the indispensability of the UN’s role as an “honest broker” in conflict areas. But over the next eighteen months he would see for the first time how little the UN flag could mean to those consumed with their own grievances and fears. Lebanon was the place where Vieira de Mello’s youthful absolutism began to give way to the pragmatism for which he would later be known.

“A SERIES OF DIFFICULT AND SOMETIMES HOMICIDAL CLIENTS”

In 1978, after a Palestinian terrorist attack on the road north of Tel Aviv left thirty-six Israelis dead, some 25,000 Israeli forces had invaded southern Lebanon. Israeli leaders said the invasion was aimed at eradicating strongholds of the Palestine Liberation Organization (PLO), which was staging ever-deadlier cross-border attacks from southern Lebanon into northern Israel with the aim of forcing Israelis to end the occupation of Palestinian territories in the West Bank and Gaza. In its weeklong offensive, Israel captured a fifteen-mile-deep belt of Lebanese territory.

1

Only the large coastal city of Tyre, and a two-by-eight-mile sliver of territory north of the Litani River, had remained in Palestinian hands. Although the United States and the Soviet Union then agreed on little at the UN Security Council, they did agree that Israeli forces should withdraw from Lebanon and that UN peacekeepers should be sent to monitor their exit.

c2 In an editorial that reflected what would prove to be a fleeting optimism about the UN, the

Washington Post hailed the decision to send the blue helmets. “Peacekeeping is the one activity in the Mideast,” the editors noted, that “the world organization has learned to do well.”

3

Peacekeeping was then loosely defined as the interpositioning of neutral, lightly armed multinational forces between warring factions that had agreed to a truce or political settlement. It was a relatively new practice, initiated in 1956 by Lester Pearson, Canada’s foreign minister, who helped organize the deployment of international troops to supervise the withdrawal of British, French, and Israeli troops from the Suez region of Egypt.

4 Soon afterward the UN Security Council had sent some 20,000 UN peacekeepers to the Congo, where from 1960 to 1964 they oversaw the withdrawal of Belgian colonial forces and attempted (unsuccessfully) to stabilize the newly independent country. Smaller UN missions in West New Guinea,Yemen, Cyprus, the Dominican Republic, and India/Pakistan had followed.

5 The UNIFIL mission in southern Lebanon was given an annual budget of around $180 million. Its 4,000 troops—later increased to 6,000—made it the largest UN mission then in existence.

6

In the three and a half years that had elapsed since UNIFIL’s initial deployment in 1978, Israeli forces had refused to comply with the spirit of international demands to withdraw, handing their positions to their proxy forces, while Palestinian forces had failed to disarm. The resolution establishing the mission had given PLO guerrillas the right to remain where they were.

d The UN mission’s flaws were thus obvious. The major powers on the Security Council were not prepared to deal with the gnarly issues that had sparked the Israeli invasion in the first place: dispossessed Palestinians and Israeli insecurity. And the Council had given the peacekeepers no instructions as to what to do if the parties continued to attack one another, as they would inevitably do.

By the time of Vieira de Mello’s arrival in southern Lebanon, command of UNIFIL troops had passed to a second UN force commander: General William Callaghan, a sixty-year-old three-star Irish general who had done UN tours in Congo, Cyprus, and Israel. Vieira de Mello’s main task was to provide Callaghan with the political lay of the land. Because he had lived in Beirut for nearly two years as a boy, Vieira de Mello had long followed events in the region. But once he moved there, he set out to acquaint himself with Lebanese, Israeli, and Western diplomatic officialdom and with the region’s various subterranean militia groups.

He shared an office with Timur Goksel, a thirty-eight-year-old Turkish spokesperson who had been with the mission from the beginning. Goksel gravitated toward what he termed the “gray zones.”“You’ve got to reach out to the men with guns in their hands,” Goksel told his new colleague. “We’ll learn much more from the coffee shops and the mosques than we will from governments.” He brought Vieira de Mello with him to his unofficial meetings. “I have only one requirement,” he said. “You must take off your damn coat and tie!” Vieira de Mello came to understand how essential it was to get to know armed groups such as the Shiite militia Amal, which grew in strength during the early 1980s and would later be largely supplanted by Hezbollah, and the breakaway factions from the PLO, such as the Popular Front for the Liberation of Palestine, which often fired on UNIFIL peacekeepers. He preferred his informal meetings to those with state officials. He marveled to Goksel, “The UN is such a statist organization. If we played by UN rules, we wouldn’t have a clue what the people with power and guns were plotting.”

Vieira de Mello was amazed at the degree of disrespect accorded to the UN by all parties. UNIFIL had set up observation posts and checkpoints throughout the mission area in the hope of preventing PLO fighters from moving closer to Israel. But the fighters simply stayed off the main roads and used dirt trails to transport arms and men. And because the central Lebanese authorities did not control southern Lebanon, when UNIFIL picked up a PLO infiltrator on patrol, no local Lebanese civil administration existed to press charges. The demoralized UN soldiers simply escorted Palestinian fighters out of the border area and released them. Some found themselves arresting the same raiders again and again.

7 UN peacekeepers who challenged armed Palestinians were regularly taken hostage. On November 30, 1981, just after Vieira de Mello arrived, PLO fighters stopped two UN staff officers, fired shots at their feet, and ridiculed them as “spies for Israel.”

The Israelis were equally brazen. They made no attempt to conceal their residual presence. They laid mines, manned checkpoints, built asphalt roads, transported supplies, and constructed new positions on the Lebanese side of the border.

8 Still, because UN officials did not want to offend the most powerful military in the region, they chose not to refer to Israel’s control of the area as “annexation” or “occupation” and complained instead of “permanent border violations.”

9

The Israeli authorities did not return the favor. They threatened the peacekeepers and regularly denigrated them.

10 Back in 1975 the Israeli public had turned against the UN when the General Assembly—the one UN body that gave equal votes to all countries, rich and poor, large and small—had passed a resolution equating Zionism with racism.

e Callaghan and Vieira de Mello pleaded with their Israeli interlocutors to cease their anti-UN propaganda, arguing that it was endangering the lives of UN blue helmets, more than seventy of whom had already been killed.

Israel had handed many of its positions to Lebanese proxy forces under a Christian renegade leader named Major Saad Haddad, who delighted in sending Callaghan insolent demands.

f “I want you to know that tomorrow at 10 a.m., I am intending to send a patrol,” he wrote in a typical message. “I ask for a positive answer.”

11 Whenever the UN peacekeepers got in his way, Haddad simply sealed off the roads in his area, preventing the movement of UN personnel and vehicles. When UN equipment was stolen, which was often, neither Callaghan nor Vieira de Mello could secure its return.

The PLO had amassed long-range weapons and continued to fire them into Israel; the Israeli army and its Christian proxies regularly retaliated with raids against PLO camps and bases in southern Lebanon.Vieira de Mello’s letters and in-person protestations over the next eighteen months would convey “surprise,” “dismay,” and “condemnation”; they would insist that bad behavior by the Israelis, the Christian proxy forces, and the Palestinians would “not be tolerated”; and they would remind the parties that their transgressions would be “brought before the Security Council.” But because the peacekeepers had neither sticks nor carrots to bring to bear, his protests were generally ignored. Vieira de Mello quickly deduced that the Security Council had placed peacekeepers in an environment in which there was no real peace to keep. As was typical during the cold war, influential governments seemed to be more interested in freezing a conflict in place than they were in trying to solve it. Until the Israelis and Palestinians resolved their differences, or the powerful countries in the UN decided to impose peace, there would be little that a small peacekeeping force could do.

Powerless to deter violence, Vieira de Mello tried to do what he did best: learn. As a boy, he had been obsessed with naval warfare and had harbored dreams of joining the Brazilian armed forces. “If I hadn’t become a humanitarian,” he liked to joke, “I would have become an admiral.” Although he detested the Brazilian military regime, he never looked down upon the military as an institution, which often surprised some of his anti-war progressive colleagues in Geneva. In his early months in Lebanon, he spent nearly as much time asking General Callaghan questions on military matters as he did dispensing political advice. “It took him a while to understand the nuances associated with military people,” recalls Callaghan. “He had to get oriented around rankings, structures, equipment, deployments, communication systems, and the camaraderie that the military brings to a job.” He pressed Callaghan for tales of previous peacekeeping missions. Callaghan, an animated Irish storyteller, was eager to oblige the impatient young man. “He wanted to do the job today and now,” Callaghan recalls. “He didn’t appreciate that in this kind of situation you have to learn to count to ten as well.”

Vieira de Mello went out on foot on back trails, and he joined motorized patrols along key highways and into Lebanese villages. He knew that UNIFIL soldiers were stuck in the middle of a conflict where all the parties were more committed to their aims than the peacekeepers serving temporarily under a UN flag would ever be to theirs. “This is their land and their war,” Vieira de Mello told Goksel. “Of course they are going to outmaneuver us.”

Any single Western military force would have had its hands full stabilizing southern Lebanon, but the mishmash of countries that constituted UNIFIL was particularly disadvantaged. Callaghan’s forces came from all over the world and were of wildly different quality. In 1945 the key founders of the UN—the United States, the U.K., and the Soviet Union—had hoped that governments would place forces on standby that the Security Council could call upon when one UN member state threatened to invade another. But after the establishment of the UN, those same major powers, along with most UN member states, insisted that they needed to keep their forces on call to meet national crises as they arose, and no standby force was ever assembled. Brian Urquhart, a highly respected British intelligence officer during World War II, had been with the UN since its founding, advising each of its secretaries-general and setting up what was then a small office for peacekeeping operations at UN Headquarters. When in 1978 the Security Council had called for monitors and peacekeepers for Lebanon, Urquhart had, as usual, raised troops on the fly.

12 He borrowed units from existing UN missions elsewhere in the world, relocating an Iranian rifle company from the small observer mission in the Golan Heights and a Swedish rifle company from the UN squad in the Suez Canal zone. France, Nepal, and Norway volunteered contingents, as did Fiji, Ireland, Nigeria, and Senegal, but the forces trickled in, arriving from different entry points.

“You don’t have any say in who you get,” Callaghan said. “It’s an advantage to be multinational because you can bring to bear the political support of all the different nations. But from a military point of view, if you had a choice, this would not be the way you would go about planning and running an operation.” UNIFIL relied on fifty-three different types of vehicles—from German, Austrian, British, French, and Scandinavian manufacturers, which made it almost impossible for the vehicles to be maintained because of the vast array of spare parts needed.

13 Vieira de Mello would pick up a phrase that would become a mantra in future peacekeeping missions: “Beggars can’t be choosers.”

Most soldiers who were asked to become neutral peacekeepers had been trained in their national armies as war fighters. They often had difficulty adjusting to being inserted into volatile environments in which they were told to maintain neutrality and to use force only in self-defense. The commander of UNIFIL’s French parachute battalion constantly referred to the rival armed factions as “the enemy.” When Urquhart traveled from UN Headquarters in New York to southern Lebanon, he had to take the officer aside to explain that, unlike a soldier fighting under his national flag, a peacekeeper had no “enemies.” He had only “a series of difficult and sometimes homicidal clients.”

14Vieira de Mello had never seen the UN operate with so little clout. While working as a humanitarian for UNHCR in Bangladesh, Sudan, Cyprus, and Mozambique, he had found it frustrating merely to address the symptoms of violence—feeding and sheltering refugees in exile or preparing to welcome them home—while doing nothing to stop the violence or redress the insecurity that had caused people to flee their homes in the first place. But at least as an aid worker he had generally been able to bring tangible succor to those in need. Because he and other humanitarians were unarmed, they did not raise expectations among civilians who, when they saw UN soldiers, expected them to fight back against their attackers.

UNIFIL headquarters had been established in Naqoura, a desolate Lebanese village on a bluff overlooking the sea just two miles north of the Israeli border. When the UN had first arrived in 1978, the village had only two permanent buildings—a border customs house and an old Turkish cemetery—but it had since turned into a lively beach town that catered to the foreign soldiers and civilians.

15 Most evenings Vieira de Mello drove across the border to the Israeli town of Nahariya, where he lived with Annie and their two young sons. Because Palestinian Katyusha rockets sometimes landed near Nahariya, Annie grew practiced at bringing Laurent and Adrien into the local bomb shelter. Vieira de Mello remained in close contact with his mother, Gilda, who was in a state of such perpetual anxiety about her son’s safety that she developed acute insomnia, a condition that would not abate even after he left the Middle East.

When he first began traveling from southern Lebanon to Beirut, which still experienced violent flare-ups despite the truce in the civil war, he too was skittish. Once, while he was attending a meeting with the speaker of the Lebanese parliament, the sound of a heavy exchange of fire drew near. Unsure of what was occurring in this, his first live combat zone, he passed a note to Samir Sanbar, a UN colleague based in Beirut. “Are we finished?” his note read. “Is this our end?” Sanbar assured him that they were not in immediate danger, and the meeting concluded uneventfully. “At the start Sergio was new to war,” recalls Sanbar. “After a few more trips to Beirut, he learned that gunfire was as natural a background noise as the sound of passing cars.”

On most of his trips to the Lebanese capital, Vieira de Mello stopped into Western embassies to urge the Irish, Dutch, French, and other diplomatic staff to persuade their governments to extend or expand their troop contributions to UNIFIL. He had a sense of foreboding and knew reinforcements were needed. Vieira de Mello also made a point of stopping in to see Ryan Crocker, the thirty-two-year-old head of the political section at the U.S. embassy and a fluent Arabic speaker. The two men would cross paths again in 2003 in Iraq, where Crocker would serve as a senior administrator in Paul Bremer’s Coalition Provisional Authority.

g Vieira de Mello immediately won over the U.S. diplomat by telling him, “People say you know your way around. I could really use your help.” As Crocker remembers, “Nothing quite succeeds so well as carefully constructed flattery. He had me.”

In fact, each man had something to offer the other. U.S. diplomats, unlike their European counterparts, were prohibited from making contact with terrorist groups. Thus Crocker came to rely on Vieira de Mello for his insights into the PLO and other armed groups. He also valued his read on southern Lebanon. “I was wild with jealousy that he could talk to people I couldn’t,” Crocker recalls. “Whenever I thought, ‘Oh my God, are we falling off the edge here?’ or ‘What does this mean?’ he’d be the guy to bounce things off of.”

FALLING OFF THE EDGE

In February 1982, sensing mounting Israeli hostility toward the PLO, Vieira de Mello met with Yassir Arafat in Beirut and warned him that if he did not remove PLO fighters from the UN area, the Israelis would likely take matters into their own hands.

16 Abu Walid, Arafat’s chief of staff, gave his “word of honor” that “not one single violation” of the cease-fire was the fault of the PLO.

17 Met with such lies, Vieira de Mello knew the UN’s efforts at mediation were hopeless.

UN officials and Western governments began to fear a second, all-out Israeli invasion. In April 1982 Urquhart, in New York, wrote to General Callaghan in Lebanon: “There is great concern in virtually all quarters here tonight about immediate future Israeli intentions. We have no firm facts to go on but I felt you should be aware of mood here.”

18 The two men drew up contingency plans. They agreed that since the Security Council had neither equipped nor mandated the peacekeepers to make war, the blue helmets would stand aside in the event of an Israeli attack. Urquhart was so firm a believer that peacekeepers should avoid using force that when asked once why UN soldiers did not fight back, he said: “Jesus Christ is universally remembered after 2,000 years, but the same cannot be said about his contemporaries who did

not turn the other cheek.”

19 All UN units in southern Lebanon were informed that the Israelis might soon launch “an airborne, airmobile, amphibious or ground operation, or a combination of these.” In the event of an invasion, Callaghan cabled his troops, the UN radio code signal would be “RUBICON.”

20

The tenuous cease-fire was falling apart and the propaganda war was escalating. On April 21 Israel launched massive air raids against PLO targets in southern Lebanon. It did the same on May 9, and PLO fighters in Tyre fired rockets into northern Israel for the first time in nearly a year. UNIFIL’s chief medical officer in Naqoura began to investigate hospital facilities in Israel, Lebanon, and Cyprus in the event that the UN took mass casualties in a new war.

21

On June 3, 1982, a gunman with the Abu Nidal organization, which the Israelis accused of being linked to the PLO, shot Shlomo Argov, the Israeli ambassador to the United Kingdom, outside the Dorchester Hotel in London.

22 On the morning of June 6, General Rafael Eitan, the chief of staff of the Israeli army, summoned Callaghan to Zefat in Israel, some twenty miles from UNIFIL headquarters. Vieira de Mello accompanied his boss and took notes. As soon as the UN team sat down, Eitan told Callaghan that the Israeli army was about to “initiate an operation” to ensure that PLO artillery would no longer reach Israel. Eitan said he “expected” that UN troops would not interfere with the Israeli advance.

23

Callaghan was enraged both by the invasion and by Eitan’s ploy to pull him away from the UN base just as the attack was being staged. “Israel’s behavior is totally unacceptable!” the Irish general exclaimed. Eitan was unmoved. “Our sole targets are the terrorists,” he said. “We shall accomplish our mission as assigned to us by our government.” He told Callaghan that UN resolutions were “a political matter for politicians to deal with,” and that twenty-eight minutes hence Israel would embark on its military operation.

24 Callaghan knew that he had to alert his troops immediately. Out of radio range, he had no choice but to deliver the coded message—RUBICON—on an Israeli army phone.

25 And remarkably the real humiliation had not yet begun.

At 11:00 a.m. Israel launched Operation Peace in Galilee and reinvaded Lebanon. It attacked with some 90,000 troops in 1,200 tanks and 4,000 armored vehicles, backed by aircraft and offshore naval units. Israeli troops poured into the country across a flimsy wire fence at the border, and they cut through UN lines—“like a warm knife through butter,” as Urquhart later described it.

The invasion did not come as a shock. In recent days all UN personnel had heard the sonic boom of Israeli war planes overhead and had seen the Israeli fleet line up in hostile formation off the coast. Vieira de Mello’s mind raced to Annie and their two sons, who were nearby. When he got back to Naqoura and reached her on the telephone, she was frantic with worry. “Sergio, I have never seen so many tanks in my life. The street is packed with them. What is going on?” He said, “They’re coming here.” He assured her that the Israelis would not dare to target the UN itself, but he told her to take the boys to the nearby shelter, where they would be safe in the event that the Palestinians fired their rockets from Tyre. He told her that as soon as Israeli troops allowed UN officials to cross into northern Israel, he would evacuate them back to France, which he did within several days.

UNIFIL peacekeepers were armed only with light defensive weapons, and one Norwegian soldier was killed by shrapnel the day of the invasion. Most got out of the way of the Israeli assault.

26 However, a few mounted resistance. On the coastal road leading north to Tyre, Dutch soldiers planted iron beams in front of an Israeli tank column, ruining the tracks of two oncoming tanks. Elsewhere a French sergeant armed only with a pistol stopped an Israeli tank as it rounded a curve. Thinking the tank was traveling alone, the peacekeeper told the Israeli driver that he had no business entering the UN zone. The tank driver pointed to the curve behind him and said, “Well, you might stop me, but there are 149 tanks just like this one behind me. What are you going to do about them?”

The Israelis had initially invaded to push the PLO out of rocket range, but once deep inside Lebanon, they kept going. On June 10 they reached the outskirts of Beirut, from where they encircled the city and cut off PLO exit routes. A week later they laid siege to West Beirut, where some 6,000 PLO fighters were cloistered, causing heavy damage to the town and killing more than 5,000 Lebanese.

27Though he knew he was living through one of the lowest moments in UN history, Vieira de Mello was initially exhilarated. He had never before found himself at the center of such high-stakes political drama. Overnight UN statements made in the sleepy town of Naqoura were suddenly capturing global headlines. Once Annie and the boys had flown back to Europe, he based himself at UNIFIL headquarters full-time.

Vieira de Mello’s main diplomatic task in the weeks after the invasion was convincing the PLO that the UN was not in cahoots with Israel. Leading Palestinian officials pointed to Callaghan’s meeting with Eitan the day of the invasion as evidence of collusion. Arafat accused UNIFIL of helping the Israelis “stab the Palestinians in the back.”

28 The Palestinian deputy representative at the UN in New York denounced the entire institution and said, “We feel this action by the United Nations and by the Israeli invading force has dealt a serious blow to the whole concept of peace-keeping and credibility of the UN.”

29

Vieira de Mello defended the UN’s honor. He drafted a cable to PLO leaders on Callaghan’s behalf, angrily pointing the finger back at the Palestinians for provoking the Israeli invasion. In light of their “unwarranted accusations of collaboration,” he reminded them that the Palestinians had infiltrated the UN area, hijacked UN vehicles, and attacked UN personnel. Since the Palestinians had ignored UN warnings and egged on the Israelis, they should “accept full responsibility” for the invasion.

30 Although both Callaghan and Vieira de Mello were even angrier with the Israelis, they knew the invaders controlled the area. Callaghan requested that UN officials in New York “avoid any open criticism of the Israelis as this will surely be counterproductive.”

31As soon as the whirlwind of the initial invasion had passed, the morale of UN peacekeepers—Vieira de Mello included—plummeted. Israel had thumbed its nose at the Security Council resolutions that demanded that Israel stay out of Lebanon, and in the course of invading a neighbor, its forces had trampled on the UN peacekeepers in their way. “We were never going to stop a determined Israeli offensive,” Vieira de Mello wistfully told Goksel, “but do you think we could have made it just a little harder for these bastards? The UN looks pathetic.” The troops serving the UN had been humiliated, but they would return home to their national armed services.Vieira de Mello had come to cherish the UN flag almost as much as he did Brazil’s, and the sting of the invasion would linger.

Callaghan was adamant that, however humiliating it might have felt, peacekeepers had been right not to contest the Israelis. “Soldiers don’t like to be marched through, no matter where they come from,” Callaghan said. “But I am the man answerable for these soldiers’ lives. What if I launch an operation against this invasion and twenty of my soldiers are killed? I do not have a mandate to risk the lives of soldiers equipped for self-defense.” He agreed with Urquhart that lightly armed UN peacekeepers could succeed only if the heavily armed warring parties kept their promises.

After witnessing Callaghan’s sputtering protests on the day of the invasion, Vieira de Mello told colleagues he was sure of one thing: “I will never use the word ‘unacceptable’ again.” There seemed little point in issuing shrill denunciations with nothing more than moral outrage behind them.

“SORRY STATE OF AFFAIRS”

UNIFIL had been sent to Lebanon to monitor Israeli troop withdrawals and restore Lebanese sovereignty in the south. Now that Israel had reinvaded and occupied Lebanon outright, Vieira de Mello did not see how UNIFIL could continue. If the blue helmets attempted to remain during a full-scale Israeli occupation, he believed the neutrality of the peacekeepers would end up compromised. “We know that the Americans aren’t going to force Israel out of Lebanon this time,” he told Jean-Claude Aimé, a Haitian UN political officer who worked for the UN in Jerusalem. “Are we to watch Israeli troops mop up?” Aimé favored a UN withdrawal, and Vieira de Mello said he agreed.“If we stay and pretend nothing has happened,” he said, “it’s as if we are condoning their invasion.” He expected the Security Council to shut down the mission, and he began planning his return to Geneva.

Callaghan pointed to the good that the UN mission was doing in humanitarian terms. “Pulling out would mean conceding totally,” he argued. “The local people depend on us. We can’t leave them on their own.” Since UNIFIL had set up base in southern Lebanon in 1978, some 250,000 civilians had returned to the area. The UN peacekeepers supplied water and electricity, maintained a hospital in Naqoura (run by the Swedes), repaired public buildings and roads, and cleared the area of explosive devices. Instead of throwing out used typewriters, photocopiers, desks, or chairs, the UN donated them to local schools. The peacekeepers also staged what became known as “harvest patrols,” escorting Lebanese civilians whose farms or olive plantations were located along the front lines.

32 When he was with Callaghan, Vieira de Mello acted as though he agreed with the general. “Sergio never said, ‘I think UNIFIL should withdraw.’ Never,” recalls Callaghan. “And if that was his opinion he would have said so.”

Irrespective of whether Vieira de Mello was testing out his ideas or simply telling both men what he thought they most wanted to hear, he knew that UNIFIL officers and civilian officials would have little say in what happened next. The powerful countries on the Security Council would decide whether the UN peacekeepers would pack up and go home.

And decide they did. On June 18 the Security Council extended UNIFIL’s mandate.

33 Four years after the blue helmets had been sent in to monitor Israel’s withdrawal, they were now being asked, temporarily, to submit to an Israeli occupation and restrict their role to delivering humanitarian aid. “The Security Council told us to stay,” recalls Goksel, “but they basically told us there was nothing for us to do. The signal we got was, ‘Do what you can to justify your salaries.’ We felt useless. We hid in Naqoura and tried to become invisible. After that, even Sergio didn’t want to go around saying, ‘I’m a UN guy.’”

Vieira de Mello repeatedly telephoned UN Headquarters in New York in search of consolation. It was the first time in his life that he was part of something that was being publicly condemned and ridiculed. He insisted on replaying June 6, the day of the invasion, again and again. “Is there something else I could have done?” he asked Virendra Dayal, the UN secretary-general’s chief of staff with whom he had worked in Bangladesh. Dayal tried to soothe his colleague. “Sergio, what could you as a young man have done all by yourself in the face of a massive land, air, and naval invasion?” Dayal wanted him to pass through New York on his way to Brazil for home leave in July. He thought a debriefing might help. But when he reached New York,Vieira de Mello just kept up his second-guessing. “Stop lacerating yourself,” Dayal urged. But his junior colleague was adamant: “We should have made more of a show,” Vieira de Mello said.

However degrading it had been to be part of the UNIFIL mission before the Israeli invasion, it felt far worse afterward. When Vieira de Mello returned to Lebanon after his leave, he found that Israeli forces were keeping UN officials largely pinned down to the UN base in Naqoura. The Israelis seemed to hope that their invasion would cause the peacekeepers to leave. They closed the Lebanese-Israeli border to UN personnel and vehicles at will, blocking resupply and personnel rotation convoys, and they denied UN personnel flight permission except for rare medical emergencies. The Israeli press suggested that the UN was passing information to Palestinian terrorists about Israeli military positions. In a cable to Urquhart, Callaghan criticized Israel’s “official smear campaign” against UNIFIL and begged UN officials in New York to approach the Israeli delegation so as “to put a firm stop to this sorry state of affairs.”

34Vieira de Mello staged small acts of civil disobedience, refusing to submit requests for travel permits to the Israeli authorities, moving around without escorts, and often sitting in his vehicle at Israeli checkpoints in the hot sun for entire afternoons, refusing to allow the Israelis to search his car. “We are the United Nations,” he would fume, sometimes astonishing Goksel. “Can’t you see the flag? We will not submit to the will of an illegal occupying force.” When he briefed incoming units of peacekeepers, he gave them the same advice he himself would receive from friends before leaving for Iraq in 2003, urging them to avoid close association with the occupiers, so as to maintain the faith of the populace.

After Vieira de Mello received his doctorate in 1974, Robert Misrahi, his adviser, had persuaded him to pursue a “state doctorate,” the highest and most competitive degree offered by the French university system. Vieira de Mello had done so, working intermittently but intensely on what he considered to be his most ambitious philosophical work. The only bright side to the paralysis of the UN mission in Lebanon was that he had time to dive more deeply into his thesis in a region where many of his ideas were being tested. When he corresponded with Misrahi, he lamented the inadequacy of philosophical tools. “Things are much more complicated in practice,” he told his professor. “Philosophical ideas must be applicable on the ground, and the field should be their only judge, their only criteria.”

35 When Misrahi visited Israel on personal business, he met with his pupil and applauded his attempts to apply philosophy to his humanitarian and diplomatic work. But he thought Vieira de Mello could not expect mere reason and dialogue to yield conversion when little mutual understanding existed among the factions. “Just going and meeting with the enemy is not enough to establish reciprocal respect,” Misrahi insisted, urging him to take a longer view of human progress. “History is slow,” Misrahi says. “Vieira de Mello thought it could be quick.”

36

The Israeli invasion had chased the PLO and Yassir Arafat north to Beirut. The Palestinians were encircled. Fearing a massacre and hoping to end the siege peacefully, the United States, France, and Italy decided to deploy a Multinational Force, totally separate from the UN peacekeeping mission that was based in the southern part of the country. In August 1982, 800 U.S. troops, 800 French, and 400 Italians assisted with the evacuation of besieged Palestinian fighters and fanned out to the outskirts of Beirut to protect the sprawling settlements filled with Palestinian refugees.

37 After some 15,000 Palestinians and Syrians left West Beirut, Arafat himself made his way to Greece, and then went on to Tunisia.

The Western forces departed almost as quickly as they had arrived, retreating from Beirut on September 10, 1982, under banners of MISSION ACCOMPLISHED.

38 With their exit the responsibility for ensuring the safety of the remaining half-million Palestinian civilians in Lebanon passed to the Lebanese government, which was weak and divided. When Bashir Gemayel, the newly elected Christian president of Lebanon, was assassinated on September 14, Israeli-backed Christian militia intent on exacting revenge closed in on the Palestinian camps. Speaking from Rome, Yassir Arafat pleaded for the Multinational Force to return: “I ask Italy, France and the United States: What of your promise to protect the inhabitants of Beirut?”

39 On September 16, as Israeli soldiers looked on, the militia forces entered the undefended Palestinian camps of Sabra and Shatila in Beirut. In the two days that followed, in the name of flushing out Palestinian terrorists, the militia murdered more than seven hundred men, women, and children.

40

On September 20, 1982, largely in response to the massacres, President Ronald Reagan announced his intention to redeploy U.S. Marines to Beirut. “Millions of us have seen pictures of the Palestinian victims of this tragedy,” Reagan said. “There is little that words can add, but there are actions we can and must take.”

41 The Western countries that had sent armed contingents in August now offered larger forces: 1,400 American soldiers, 1,400 Italians, and 1,500 French (including 500 who were reassigned from UNIFIL) returned to Lebanon, accompanied by armored vehicles, mortars, and heavy artillery.

42 Initially, their presence seemed to calm tensions.

Israel’s fight, up until that point, had been with the Palestinians. But with their occupation of Lebanon, Israeli forces began to meet new resistance—that of Lebanese Shiites. In January 1983, with the UNIFIL mandate in southern Lebanon up for renewal again, Urquhart flew to Jerusalem and met with the Israelis, whose occupying forces were suffering a growing number of casualties. In his notes on the trip, he wrote that he observed “a genuine desire amongst intelligent Israelis to get out of Lebanon before it overwhelms them. They have certainly bitten off more than they can chew.”

43 The Israelis would not withdraw from Lebanon for eighteen years. They would lose 675 soldiers there.

Urquhart’s visit to Lebanon gave Vieira de Mello his first chance to spend time with a legendary UN figure. For once he made a terrible impression. After they had dinner together in a Turkish restaurant, Urquhart wrote in his diary that Vieira de Mello had

a very severe case of localitis and constantly lecture[d] and boom[ed] at one about the iniquities of the Israelis, the humiliating position in which UNIFIL finds itself, etc., etc. I got rather annoyed at this and pointed out to de Mello that since he had been in UNIFIL nothing has happened to compare with all the things that had happened before, not to mention the experiences that some of us had had in other parts of the world, and that humiliation was in the eye of the observer.

Urquhart concluded his entry with a stinging verdict on his ambitious young colleague. “He has become a great prima donna and cry-baby, and I think he should be sent back to the High Commissioner for Refugees as soon as possible.”

44TAKING SIDES

For all of his frustrations as a UN official, Vieira de Mello knew that the Multinational Force in Beirut wasn’t faring much better. On his periodic trips to the capital, he continued to see Ryan Crocker at the U.S. embassy. Entering an American embassy in the 1980s was nowhere near as challenging as it would later become. Like any visitor, he could walk right past a Lebanese army checkpoint, up the driveway, and into the main lobby of the eight-story building. Only then would he present his ID card and make his business known to U.S. guards.

At 1:05 p.m. on April 18, 1983, when Vieira de Mello was back in southern Lebanon, a man in a leather jacket drove a black delivery van with five hundred pounds of explosives through the embassy’s front entrance. The blast, which destroyed the van and all traces of its driver, killed fifty people, including seventeen Americans. It was the first-ever suicide bomb attack against a U.S. target, the opening salvo in an unconventional battle that would not command significant high-level attention until the al-Qaeda attacks on U.S. soil on September 11, 2001.

When Vieira de Mello next saw Crocker, who had narrowly escaped the blast, the two men commiserated on the impossible task of putting Lebanon back together again. “This is a hopeless mess,” said Vieira de Mello. “I see no way out that is going to be good for anyone—not the UN, the Lebanese, the U.S., nor Israel. No way out whatsoever.” Crocker agreed. “There is a new player on the court out there,” the U.S. diplomat noted, “and this player is definitely changing the rules of the game.” They wondered aloud how this new breed of Islamic fighter willing to die for his cause would be suppressed.

Vieira de Mello’s tour in Lebanon was winding down, and in his last weeks he tried to ensure that a small incident would not ignite a far larger one. On March 30, 1983, a jumpy Fijian soldier manning a UN checkpoint had shot and killed a highly respected forty-year-old Lebanese doctor named Khalil Kaloush. Upon learning of the incident, Vieira de Mello, Goksel, and a small UN delegation proceeded to Kaloush’s hometown to meet with the village chiefs, who demanded compensation, or “blood money.”

45When the grieving family rejected Vieira de Mello’s request to attend the funeral, he had UNIFIL send a floral wreath, which the family also turned away. But he didn’t give up, visiting the Kaloush family multiple times and telling them that he understood that the UN had to pay up. Dr. Kaloush’s widow asked that the couple’s four children, who ranged in age from four to ten, be educated. Over a ten-year period this would cost around $150,000.

Vieira de Mello knew that the New York bureaucracy was no match for a tribal culture prone to exacting swift revenge. UN administrative staff initially told him that the hurdles would be insurmountable. But after weeks of badgering, he finally received permission to dispense the funds.

46 In one of his few victories in eighteen months in Lebanon, on June 23, he delivered the payment to Mrs. Kaloush. A week later his Lebanon mission came to an end, and he returned to Geneva.

Back at a desk at UNHCR, Vieira de Mello watched, horrified, as the Western troops in the Multinational Force in Beirut ratcheted up their fire-power against the Lebanese armed groups. U.S. warships off the coast of Beirut and U.S. Marines in the city offered military backing for the beleaguered Lebanese army, which was at war with other Lebanese armed groups. In September and October six U.S. servicemen were killed in action and fifty were wounded. In a lengthy analysis in October 1983,

New York Times Beirut correspondent Thomas Friedman described the shift: “Without anyone really noticing it at first, the Marines here have been transformed during the last month of fighting from a largely symbolic peacekeeping force—welcomed by all—to just one more faction in the internal Lebanese conflict.”

47 Vieira de Mello disapproved of what was occurring. “They have taken sides,” he noted to a colleague. “They’ve lost any appearance of neutrality. And when you throw neutrality away, you better hope you’ve chosen the right side.”

On October 19, 1983, at a televised press conference in Washington, D.C., a Washington Times reporter and former U.S. Marine named Jeremiah O’Leary asked President Reagan why U.S. troops had set up their base at Beirut airport on flat terrain instead of finding high ground elsewhere in the city. Reagan said that since the Marines in Lebanon were not performing a traditional combat role, they observed different rules. U.S. forces were peacekeepers, he said, not war fighters.

Four days later, at around 6:20 a.m., a yellow Mercedes truck carrying 2,500 pounds of TNT entered an empty public airport parking lot, circled the parking lot twice so as to pick up speed, and plowed through a six-foot-high iron fence around the U.S. Marine barracks. By the time the U.S. sentry guarding the compound had installed a bullet clip into his previously unloaded gun, the truck had already barreled past. A fourteen-foot-long, f oot-and-a-half-thick black barrier usually helped block the building entrance, but Marines had removed it the previous day for a Saturday-afternoon country-western concert and pizza party.

48 Although one Marine fired on the oncoming vehicle and another threw himself in front of it, the truck easily plowed into the lobby of the four-story building. When the driver detonated his explosives, the blast blew bodies out of the building as far as fifty yards away and left a crater thirty feet deep and forty feet wide.

49 A total of 241 American servicemen were killed in what was at that time the deadliest terrorist attack that had ever been carried out against Americans.

50

Initially President Reagan was defiant. Appearing with his wife, Nancy, his voice trembling, the president decried the “bestial nature” of the attack and stressed that such people “cannot take over that vital and strategic area of the earth or for that matter any other part of the earth.”

51 He quickly dispatched three hundred more U.S. troops. “Many Americans are wondering why we must keep our forces in Lebanon,” Reagan said. “We cannot pick and choose where we will support freedom.”

52 Defense Secretary Caspar Weinberger suggested that Moscow might be behind the suicide attack. “The Soviets love to fish in troubled waters,” he said.

53 In a formal address to the nation Reagan described the good that U.S. forces were doing, staving off Soviet influence, stabilizing a “powder-keg” region, safeguarding energy resources, and protecting Israel. “Would the terrorists have launched their suicide attacks against the Multinational Force if it were not doing its job?” he asked.

54 Reagan appointed a new Middle East envoy. He chose a man who had served as secretary of defense under President Gerald Ford and who would again serve as secretary of defense under George W. Bush: the fifty-one-year-old Donald Rumsfeld.

The U.S. public was angered by the death toll, the continued sniper and shelling attacks against Americans, and the confusion about what U.S. troops were doing in Lebanon.

55 Although Reagan initially ignored the public unrest, by February 1984 he had announced that he was “re-concentrating” U.S. forces. The last of the Marines had left by the end of the month. With Congress crying, “Bring our men home,” Reagan complained, “All this can do is stimulate the terrorists and urge them on to further attacks.”

56

In 2003, on the twentieth anniversary of the attack on the Marine barracks, Defense Secretary Rumsfeld would say that his experience as Reagan’s envoy in Lebanon had shaped his approach to fighting twenty-first-century terrorism. When U.S. forces left Beirut in 1984, Rumsfeld said, the United States had mistakenly shown extremists that “terrorism works.” In the wake of the 9/11 attacks, by contrast, Washington would “take the war to them, to go after them where they are, where they live, where they plan, where they hide.”

57 He noted, “We can’t simply defend. We can’t hunker down and hope they’ll go away.”

58 That, for Rumsfeld, was the “lesson of Lebanon.”

Vieira de Mello drew a different lesson. Any doubts he had about whether UNIFIL should have fought back in the face of the Israeli invasion were dispelled. If UN peacekeepers were to surrender their neutrality, as the troops in the Multinational Force had done, they would be viewed as combatants. He had come to appreciate the tangible virtues of the UN’s commitment to impartiality. More than a decade would pass before—in a peacekeeping mission in the Balkans—he would realize that impartiality too carried grave risks.