Five

“BLACK BOXING”

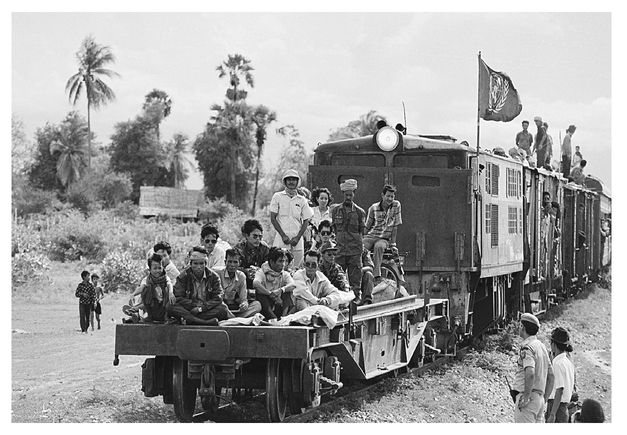

Cambodian refugees returning to their country on the UN-renovated Sisophon Express.

As a student of philosophy Vieira de Mello had often pondered the nature of evil. But in Cambodia he actually got to know some of the world’s most feared mass murderers. Soon after arriving in Phnom Penh, he had visited the Tuol Sleng torture and execution center, where the Khmer Rouge had murdered as many as 20,000 alleged opponents and which Hun Sen’s government kept open as a museum. Although he was thoroughly revolted by the photos of executed men and women of all ages, he was absolutely convinced that he and other UN officials had to engage potential spoilers. He was convinced that peace hinged upon whether the UN could secure the Khmer Rouge’s cooperation. For many humanitarians the prospect of working with the Khmer Rouge was loathsome. Human rights advocates had criticized international mediators for glossing over Khmer Rouge crimes—deliberately avoiding the word “genocide” in the Paris agreement, for instance, and stipulating euphemistically that the signatories wished to avoid a return to “past practices.” But Vieira de Mello believed in what he called “black boxing.” “Sometimes you have to black box past behavior and black box future intentions,” he told colleagues. “You just have to take people at their word in the present.” He returned to Kant’s admonition, “We should act

as if the thing that perhaps does not exist, does exist.”

1

The Khmer Rouge were bitterly disappointed by UNTAC’s performance. They had expected Akashi and the UN Transitional Authority to take charge of Cambodia and end Vietnamese influence in the country. But while the Paris agreement had authorized the UN to take direct control of the key ministries, a mere 218 UN professionals—95 in Phnom Penh and 123 in the provinces—had been tasked to supervise the activities of some 140,000 Cambodian civil servants in Hun Sen’s government, and almost none of the UN officials spoke Khmer.

2 UNTAC’s role was thus inevitably more advisory than supervisory.

Akashi had also proven reluctant to exercise the authority and capacity that he had actually been given by the Paris agreement. Although he was supposed to take “appropriate corrective steps” when Cambodian officials misbehaved, he rarely reassigned Cambodian personnel. He told colleagues that because the Japanese constitution had been imposed by Douglas MacArthur and the American occupiers after World War II, it had lacked legitimacy with many Japanese. He believed that the UN would alienate Cambodians if it tried to impose its vision. When the Khmer Rouge saw that Akashi intended to take a minimalist approach to his job, they began to renege on the commitments they had made in Paris. If Hun Sen would not relinquish control of the key ministries or purge the Vietnamese, the Khmer Rouge would in turn deny UNTAC access to its territory. None of the factions that had been at war since the early 1970s agreed to disarm.

CHARMING THE KHMER ROUGE

Vieira de Mello set out to get to know the Khmer Rouge leadership. While UN officials who worked in the camps at the Thai border had met with mid-level Khmer Rouge officials over the years, no international official had yet met with senior Khmer Rouge leaders on their turf. He was determined to become the first. “Part of him thought, ‘What kind of feat would it be if I could be the one to bring the Khmer Rouge to heel?’ ” recalls Courtland Robinson, a longtime analyst of Cambodian affairs.

But Vieira de Mello had other motives. He had always been intrigued by the question of how Khmer Rouge revolutionaries like Ieng Sary, Pol Pot, and Khieu Samphan could have studied in Paris, even reading the same philosophy tracts as he had at university. “I want to look into Ieng Sary’s eyes,” he told Nici Dahrendorf. “I want to see if they are still burning with ideological fire.” At this stage in his career, mulling the roots of evil was more stimulating than managing the logistics of easing the suffering that resulted from that evil. Late at night, as he sat in his hotel suite with McNamara, Bos, and a bottle of Black Label, he could debate the Khmer Rouge’s history into the early-morning hours. “How did they go astray?” he asked. “Was there a moment where they turned down the wrong path, or was the ideology destined to be carried to its extreme? And if it was going to be carried to the extreme, was the extreme destined to be murderous?” McNamara did not believe the Khmer Rouge could change their ways. He was known around the mission for declaring, “Let’s give ’em hell.” By contrast, Vieira de Mello rarely pushed the parties to go much beyond where they had proven themselves inclined to go. “Will you for once think of the morning after we give them hell, Dennis?” he asked. “I give them hell, but what happens then? They won’t return my calls ever again.” William Shawcross, the British journalist, teased Vieira de Mello that his eventual autobiography would be aptly titled My Friends, the War Criminals.

One day Salvatore Lombardo, the Italian UNHCR official, entered the dusty UN office in Battambang to find his boss Vieira de Mello sprawled out on the couch reading Kant’s Critique of Practical Reason in French. “Sergio, what the hell are you doing?” Lombardo asked. Vieira de Mello replied without raising his eyes from the text: “This is the only kind of reading I can do that enables me to actually escape this place.” Kant was fresh in his mind because he had recently delivered his lecture at the Geneva International Peace Research Institute. He brought the paper to Cambodia and excitedly shared it with Bos, who made a valiant effort to navigate his prose but could never follow the argument. “No matter how I tried, I would either fall asleep after two pages, or put it down in frustration at my inability to understand it,” she recalls. He pretended as though it didn’t matter, but she noticed that he kept leaving it lying around their hotel room in the not-so-subtle hope that she might get a second wind.

In some sense, Vieira de Mello’s desire to charm the Khmer Rouge was rooted in his general desire to keep everyone on his side. A few years before, when he had been UNHCR’s director of the Asia Bureau in Geneva, he had asked Douglas Stafford, the deputy high commissioner, to replace a country director in Indonesia who was terrorizing the staff, and one in Hong Kong who was drinking too much. But when Stafford reviewed the personnel files, he saw that Vieira de Mello had given both employees “outstanding” reviews. “Without a paper record of incompetence or abusiveness, how am I supposed to help you get rid of these people?” Stafford asked. “Why did you mark them ‘outstanding’?” Vieira de Mello was unapologetic. “You never know where you are going to end up,” he said. “One day you could be that person’s boss. The next day you could be working for them. Why make an enemy when you don’t have to?” Stafford commented to a colleague, “You know what Sergio’s biggest problem is? He refuses to make enemies.”

While ambition, intellectual curiosity, and this refusal to make enemies certainly played a role in steering Vieira de Mello toward the Khmer Rouge, he also knew that the Paris agreement was hanging in the balance. If the Khmer Rouge stopped cooperating with the UN altogether, war could restart. Since the Maoist guerrillas controlled several refugee camps on the Thai border, they could refuse to allow “their” 77,000-plus refugees to return to Cambodia. Or they could sabotage the UN-sponsored elections less than a year away by shooting at Cambodians who headed out to vote.

It was never clear exactly who was in charge of the Khmer Rouge. Neither Brother Number One (Pol Pot) nor Brother Number Three (Ieng Sary), the group’s best-known leaders, showed their faces in Phnom Penh. Khieu Samphan, the public face of the Khmer Rouge, tape-recorded his meetings with UN officials, giving rise to speculation that he was sending the tapes to Pol Pot. For insight on the Khmer Rouge, Vieira de Mello relied most closely upon a thirty-four-year-old American named James Lynch. A former corporate lawyer from Connecticut, Lynch had helped Cambodian refugees resettle in the United States as a pro bono service for his law firm and then moved to Thailand in order to take up a job processing refugee asylum requests. Lynch had spent half a decade negotiating with Khmer Rouge officials at the Thai border, and Vieira de Mello asked him to arrange for him to travel deep into the bush to meet them.

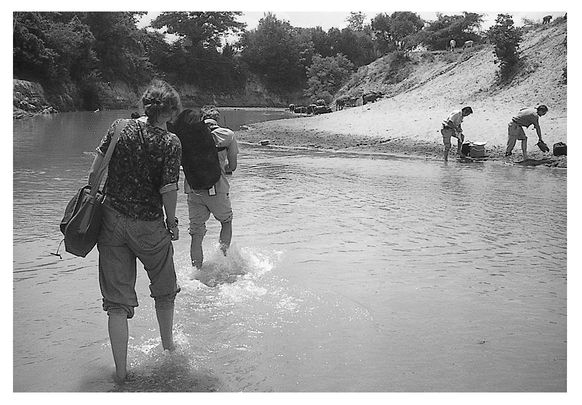

On April 6, 1992,Vieira de Mello, Bos, and Andrew Thomson headed out with a de-mining expert, an agricultural engineer, and Udo Janz, the head of the UNHCR office in Battambang, Cambodia’s second-largest town. Lynch and Jahanshah Assadi were to drive from Thai territory and join Vieira de Mello and the others at the Khmer Rouge base camp. Heading into dangerous territory, the UN team did not spell out their plans to their Cambodian army escorts. But as they approached the Mongkol Borei River, one of the escorts Hun Sen’s government had provided exclaimed, “We aren’t going any further. This is suicide!” They had never before skirted Khmer Rouge territory, and they hurriedly abandoned the UN group.

The bridge that the UN team had been instructed to cross had been blown out. Perched atop a riverbank at the edge of Khmer Rouge territory, the staff looked to Vieira de Mello for guidance. His plan began to look simultaneously wildly ambitious and shockingly amateurish. But suddenly he pointed across the river. “Look!” he proclaimed gleefully. “They’re here!” Standing atop the opposite riverbank were three Khmer Rouge soldiers, carrying Kalashnikovs and wearing Mao caps, khakis, and their trademark kerchiefs. “Go talk to them, Doc,” he instructed Thomson, the group’s only Khmer speaker. “See if they are our guides.”

Thomson stared at Vieira de Mello in disbelief. Ever since he had moved to Cambodia in 1989, the New Zealander had experienced a recurrent nightmare, influenced by the Academy Award-winning film The Killing Fields. In the dream, while he slept in his tent in an Australian Red Cross hospital, a Khmer Rouge cadre in black pajamas waded through a field of rice paddies, entered the back of the tent, dragged Thomson outside, and executed him. In the two years he had spent in Cambodia before joining the UN, he had never met a Khmer Rouge soldier and had sworn to himself that he never would. Although the Paris agreement stipulated that UN officials were to work with the Maoists, Thomson had lived among Cambodians too long to be able to overlook the guerrillas’ bloody past. “We were supposed to treat the Khmer Rouge like the other parties,” he recalls, “but they weren’t like the others. They were mass murderers.” Nonetheless,Vieira de Mello’s enthusiasm for the adventure had been so infectious and the case he made to Thomson about his indispensability had been so persuasive that the young doctor suddenly found himself being summoned to begin chatting with a member of a militia known to shoot without asking questions.

Thomson made his way down a twenty-foot-high sloping mud riverbank toward the shallow river below. He walked halfway across the river and changed his mind, freezing in his tracks. “Shit,” he said to himself. “I can keep going and get a bullet in the chest, or I can turn around now and get shot in the back.” The soldier on the opposite bank peered down at him, but because the sun was behind his head, Thomson could only make out the soldier’s silhouette and not his facial expression.

“Hi,” Thomson said in Khmer, quaking with fear. “Are you the Khmer Rouge?”

The soldier nodded.

“Where’s the bridge?” Thomson asked.

The soldier gazed down and answered listlessly, “There’s no bridge. You must walk across.” The UN officials would have to trust that there were no mines on the river floor if they wanted to continue their journey.

If the UN team members were to leave their vehicles behind, they would be entirely dependent on the Khmer Rouge. Without the Land Cruisers’ long-range antennas, they would not be able to maintain radio contact with the UN base. A few of the officials carried handheld radios, but the radios had neither the range nor the battery life to be of use for long. Vieira de Mello shrugged, rolled up his trousers, and headed down to where Thomson was standing. The others followed, knowing that once they crossed the river, they would be heading into the unknown.

As the single-file line of UN officials walked through the water, carrying their day packs of mosquito nets, notebooks, and bottled water, the tension and the absurdity of the encounter were such that somebody in the group began giggling, and within seconds the others had joined in. By the time they had crossed the narrow river, the entire crew was howling with laughter. The expression on the faces of their dour Khmer Rouge guides did not change.

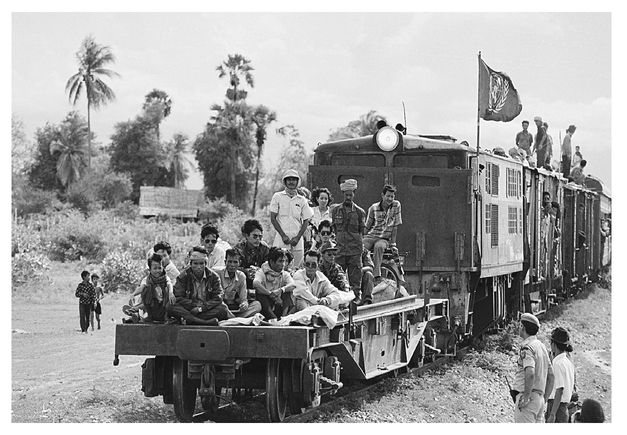

Vieira de Mello and Mieke Bos crossing the Mongkol Borei River en route to Khmer Rouge territory, April 6, 1992.

The soldiers led the UN team into the forest on a two-mile walk, warning them not to step off the trail because the woods were smothered with mines. Alongside the path the UN officials saw rocket launchers, piles of ammunition, and bunkers. “So much for UN disarmament!” Vieira de Mello exclaimed. He produced a camera and began snapping photos of the soldiers beside their weaponry. Thomson, who remained rattled, said, “Sergio, I just know you don’t want to be taking photos. They are, after all, the Khmer Rouge!” Vieira de Mello was amused. “You bet I do, Doc. I may not get the chance again.”

The group came upon a Chinese flatbed truck, which they were told to board. As the truck traveled through ever-denser brush, Vieira de Mello used sanitary wipes to keep himself clean. After around two hours of driving amid bamboo that was three stories high, the truck entered a field where two hundred Khmer Rouge soldiers were lined up as if for inspection. The UN team had reached the Khmer Rouge camp.

Lynch and Assadi had arrived several hours earlier from Thailand and had grown alarmed when they were unable to reach their colleagues on the radio. When their boss arrived all smiles, however, the two men feigned coolness. “What took you so long?” Assadi asked. Lynch was the person who had mapped out the itinerary. “How exactly did you expect us to cross that river in our car?” Vieira de Mello ribbed him.

The Khmer Rouge treated the visiting UN delegation like royalty. General Ny Korn, the Khmer Rouge military commander for the region, ushered them into a small hut, offering beer, Coca-Cola, and the most precious commodity of all—ice cubes, which had been driven in that afternoon from Thailand. Vieira de Mello had behaved much like a giddy boy on a school field trip on the journey into the jungle, but as soon as the negotiations began, he was all business. Instead of ignoring or marginalizing the Khmer Rouge, as Akashi and Sanderson were doing, he tried to convince them that in order to remain a significant political force, they would need to entice refugees to return to land under their control in Cambodia. If nobody returned to their former strongholds, they would not score well in the 1993 vote.

He told General Ny Korn that as long as the returns were genuinely voluntary, UNHCR would help Cambodians move to Khmer Rouge-held lands. And the general made it easy, quickly agreeing with the UN principle that every Cambodian refugee had the right to return to whichever area he or she chose. This meant that refugees in the Khmer Rouge-controlled camps would have the freedom to choose to leave the cultish Maoist organization and settle anywhere in Cambodia. But it also meant that those refugees who chose to move to Cambodian lands under Khmer Rouge control would get UNHCR assistance. Yet for Vieira de Mello to offer this, he told the general, the reclusive Khmer Rouge would have to grant the UN unfettered access to the area, so that experts could conduct full health, water, and mine assessments. The Khmer Rouge took the UN officials around the area and pointed to the lush vegetation and the fertile land. “The best farming land in the country,” said one. “You must tell the people in the camps.”

As the afternoon wore on, mosquitoes began to take aim at the UN visitors. Udo Janz applied roll-on mosquito repellent, and the Khmer Rouge officials at the table pointed to his device with openmouthed wonder. Janz told them that the repellent would keep mosquitoes and malaria away. One of the bolder soldiers grabbed the stick, took a whiff, and exclaimed in Khmer, “Lemon, lemon!” He then did as Janz had done, dispensing the repellent the length of his arm. On his map Thomson had placed an enormous X through the territory they were sitting in because it was known to be laden with malaria-infested mosquitoes. But when he raised the matter, a Khmer Rouge public health official said, “We don’t have malaria here. We cut down all the forests, and the malaria went away.” Thomson did a double take.“You’re trying to tell me that none of you has malaria?” he asked. “Don’t insult me by lying to me.” The Khmer Rouge official grew angry. “What do you know about my country?” he asked. Suddenly Vieira de Mello, the diplomat, broke from his conversation with General Ny Korn and placed himself between the two sparring health professionals. “I think we can all agree that malaria is a serious problem,” he said. “And of course it warrants careful consideration. You two can follow up at a later date.”

Aid workers and diplomats in war-torn areas often have to weigh offers of hospitality against potentially life-threatening consequences. In the late afternoon a Khmer Rouge soldier suggested that the UN team ward off the heat by taking a swim in the river. “We’re fine,” said Vieira de Mello, on behalf of the others. But the soldiers were insistent. “We don’t have bathing suits,” Vieira de Mello tried. General Ny Korn delivered a stern order in Khmer. Within minutes a Khmer Rouge cadre had returned with sarongs for the UN officials to wear. With trepidation, Vieira de Mello and the others eased themselves into the water, which proved immensely refreshing. The Khmer Rouge soldiers stood beaming on the banks of the river. “You see how clean the river is now,” one shouted. “When the Vietnamese ruled Cambodia, the rivers were filled with body parts and corpses.” The UN swimmers cringed at the thought of what lay beneath them. The young Khmer Rouge soldiers, most of them still teenagers, took special delight in gawking at Bos, the lone woman in the group, as she swam. “She’s torturing these poor lads,” Assadi said to Lynch. “It just isn’t fair.”

Before dinner the UN visitors heard the sound of gunfire in the distance. Thomson, who had still not relaxed, took it as a bad omen. But his fears were quickly soothed when rifle-wielding Khmer Rouge soldiers entered the camp carrying their bounty: a deer that they had shot for dinner. After the feast, the group retired to simple wooden huts, where they stayed the night sleeping on sheets that still bore the creases from having just been removed from their store wrapping.

After a final meeting over breakfast the next morning, Vieira de Mello’s UN team parted, retracing its steps. When photos from the trip made the rounds at UN headquarters in Phnom Penh, most UN officials were stunned that their colleagues had dared to make such a trip. Vieira de Mello’s cable to Geneva noted proudly that theirs was “the first official visit by international staff to the Khmer Rouge area.”

3

Ever since his stint in Lebanon, he had bristled under the label of “humanitarian.” But after his trip into Khmer Rouge territory, he made the case to Akashi that a humanitarian could play a role with profound political importance. If he could use refugee returns to open up a channel of communication to the one warring faction that no one else in the UN could reach, he could be the wedge for other parts of UNTAC to gain access and eventual cooperation. He knew his strategy was risky. The Khmer Rouge could shut down as quickly as they opened up. He wrote to Ogata that rather than trusting General Ny Korn’s assurances, UN officials had to “put this sudden forthcomingness to repeated tests in the weeks to come.”

4In fact, the Khmer Rouge “forthcomingness” did not last, as they denied access to UN peacekeepers, de-miners, and public health officials. On May 8, a month after his meeting with General Ny Korn, Vieira de Mello traveled back to forbidden territory to meet with Ieng Sary, the second-most important Khmer Rouge official, in Ieng’s villa. The journey was as adventurous as the first, involving tractors, donkey carts, and Chinese trucks. Again, upon arrival Vieira de Mello bore no signs of the stress. Accompanied by Bos, Assadi, and Lynch, he managed to remain immaculate, even as their vehicle sailed from one deep puddle to another. Lynch and Assadi were covered in mud by the time they arrived.Vieira de Mello, who once again used his wipes to remain spotless, gave his colleagues a once-over on arrival and shook his head. “I’ve wondered this my whole life,” he said, smiling, “but now I finally know what it means to look like shit.”

Ieng Sary served an even more elaborate meal than General Ny Korn had, complete with French wines and cheeses. Although Ieng spoke through a Khmer-French translator, he frequently corrected the translations. The meeting broke no new ground. Vieira de Mello urged Ieng Sary to use his clout to improve Khmer Rouge cooperation with the UN, and Ieng Sary urged Vieira de Mello to use his clout to strip Hun Sen of his power. Impressed by Ieng’s cultured ways, Vieira de Mello was again flummoxed by the disconnect between the man he met and the crimes for which he was responsible. “When you are drinking Ieng Sary’s cold Thai beer and eating filet mignon like that,” he whispered to Assadi as they departed, “it is easy to forget that the man is a killer.” Whenever Vieira de Mello met with Khmer Rouge officials, he avoided mention of the crimes of the past. As Bos recalls, “Sergio’s focus was always on the future. He was not confrontational and didn’t see the point of asking, ‘How much blood do you have on your hands?’ ”

TRANSITIONAL AUTHORITY WITHOUT THE AUTHORITY

Vieira de Mello’s inroads earned him respect from his colleagues, but they did not appear to be changing Khmer Rouge behavior. On May 30, just three weeks after he shared his banquet lunch with Ieng Sary, UNTAC suffered its lowest moment. Akashi and General Sanderson had traveled to the Khmer Rouge self-styled headquarters in the town of Pailin, where they had met with several Khmer Rouge leaders. Afterward, instead of heading back to Phnom Penh, Akashi decided that he would try to exercise the free movement promised the UN by the Paris agreement. Akashi’s convoy drove along a bumpy dirt road until it reached a checkpoint in an area where the Khmer Rouge were known to be smuggling precious gems and timber into Thailand. Two bone-thin Khmer Rouge soldiers manned the single bamboo pole that blocked the road. When Akashi asked the soldiers to lift the pole, they refused.

Akashi initially acted as though he would not be denied. He angrily demanded that the soldiers go and fetch their commander.

5 But when a more senior Khmer Rouge officer turned up, he too refused to allow the UN to proceed. Akashi did not have a backup plan and simply instructed the UN drivers to turn around. Sanderson, who had thought it ill advised to attempt to penetrate forbidden Khmer Rouge territory in the first place, defended the retreat, noting that a large machine-gun post abutted the checkpoint. But the Cambodian and Western media, who were traveling in tow, exploited the incident to ridicule UN passivity.

Cambodians had hoped that UN soldiers would enforce the terms of the Paris agreement, but that expectation was slowly giving way to a fear that the UN would bow in the face of resistance from any of the factions. “We are the United Nations Transitional Authority, without the authority,” observed one British peacekeeper. “The Cambodians are contemptuous of us.”

6 Hun Sen’s military attacks on the Khmer Rouge rose steadily from 1992 into 1993, as did the occurrences of banditry in the countryside.

Akashi and Sanderson had both made it plain that they had no intention of getting their way by using force. This was a clear-cut peace

keeping mission, and they intended to keep it that way. “Many of our troop-contributing countries were sending their soldiers on their first-ever UN missions,” Sanderson recalls. “Some hadn’t even arrived yet. How many of them would have signed on if the mission had been advertised as ‘Come to Cambodia to make war with the Khmer Rouge!’ ” Akashi blamed the factions for the stalemate—not the UN. “Blithe proponents of ‘enforcement’ seem to overlook the fact that the Vietnamese occupied Cambodia for a decade with 200,000 troops without managing to bring the country fully under their control,” he said.

7

UN officials were divided on the question of how tough Akashi and Sanderson should get with those who were sabotaging the peace. McNamara thought human rights abuses would continue to increase if Akashi allowed the UN—and, by definition, its principles—to be walked over. “I don’t see the point of having thousands of soldiers and police if one bamboo pole can stop us,” McNamara argued. Sanderson’s deputy, a French general named Michel Loridon, went further, urging UNTAC to “call the Khmer Rouge’s bluff.”

8 Loridon believed a UN mission was no different from any military mission: It demanded risk taking. “It is not a question of troop strength. I have done a lot more with 300 troops than is now being done with 14,000,” Loridon told journalists. If the Khmer Rouge fought back against UN troops, he argued, “one may lose 200 men—and that could include myself—but the Khmer Rouge problem would be solved for good.”

9 Sanderson called Loridon into his office when he saw the press reports. “Did you actually say these things?” Sanderson asked, incredulous. “

Oui, mon général,” Loridon answered, “but of course my loyalty is to you.”

Vieira de Mello did not believe that Akashi and Sanderson should have barreled through the bamboo pole. Having spent endless hours meeting with key ambassadors, he knew troop-contributing countries were not prepared to risk their soldiers’ lives to do battle with the genocidal Khmer Rouge. Vieira de Mello deemed Loridon a loose cannon, and for the rest of his career he cautioned against crossing “the Loridon line.” “Give me a few French paratroopers,” Vieira de Mello would say, mimicking Loridon, “and I’ll take care of the Khmer Rouge!” But he agreed with McNamara that the incident made the UN look spineless and that it highlighted Akashi’s weakness as a diplomat. “This is a major loss of face and blow to the credibility of the UN,” he told Bos. “The art of diplomacy is to avoid placing yourself in a position where you can be humiliated.”

Vieira de Mello got along well with General Sanderson, as he did with most senior military officers. But occasionally tensions flared up between the two men, as Sanderson faulted him for legitimating the Khmer Rouge. “You’re playing right into their hands,” the general said. But Vieira de Mello stood his ground. “Look, I have them cooperating with the UN on something. Nothing else is moving. How else are we going to keep them in the game?”

Vieira de Mello’s ties with Akashi grew strained. Akashi was obsequious toward influential diplomats in Phnom Penh, but he treated top UN officials within the mission as mere technicians. Vieira de Mello was in constant contact with UNHCR’s field offices throughout the country, and he believed he had his finger nearer the country’s political pulse than Akashi, who interacted mainly with other foreigners in the Cambodian capital.

On June 15, 1992, just as Akashi departed for a donors’ conference in Tokyo, Vieira de Mello, McNamara, and Reginald Austin, the senior UN official in charge of planning elections, authored a joint memo urging Akashi to adopt a more “participatory” management style and to overhaul UNTAC’s approach to Hun Sen and the Khmer Rouge. Because UNTAC had failed to assert control over Cambodia’s five key ministries, Hun Sen’s faction retained power it was supposed to have surrendered, and it lorded that power over the others. Whatever Akashi’s reluctance to act like a MacArthur-style occupier, the UN directors argued that he needed to take on greater authority himself so that Hun Sen would not continue to dictate events. He also needed to make use of Vieira de Mello’s back channel to the Khmer Rouge.

10When Vieira de Mello joined Akashi in Tokyo later in the week, he asked to discuss the memo. But the Japanese diplomat waved off the criticisms. “I was of the feeling that they didn’t have the breadth of information and intelligence that I had,” Akashi recalls. “So I didn’t think they were in the position to join me in decision making. They were a little overambitious, I thought.” Akashi convinced himself that the men took the brush-off in good faith. “They did not have enduring grudges,” he remembers, inaccurately. “They saw I appreciated their work and their ideas but that they were somewhat limited.”

A DANGEROUS EXPERIMENT

Vieira de Mello continued to believe that constructive engagement with the Khmer Rouge was the only way to save the faltering Cambodian peace process. In an internal July 1992 memo he instructed UNHCR officials to refrain—“in accordance with their humanitarian and non-political mandate”—from criticizing the Khmer Rouge in the press.

11 In September 1992 he chastised UN official Christophe Peschoux for telling

Le Monde that the guerrillas were falling apart.

12 He faxed the clipping to Peschoux with a handwritten note: “I need hardly point out that interviews of this kind are most unhelpful and embarrassing, particularly at a time when I am doing my best to keep channels of communication with the [Khmer Rouge] open.”

13 Denunciation and isolation had offered Akashi fleeting satisfaction, but the approach was not sustainable. “By slamming the Khmer Rouge in public, what are we gaining?” Vieira de Mello vented to Assadi.“We’ll be one voice in a million criticizing them. To them we’ll be just another enemy.”

Ever since his meeting with Ieng Sary in May, he had been lobbying Khmer Rouge officials in Phnom Penh to grant him a return visit to their rural territory. Finally, in August he got his opening after a Cambodian refugee couple, whom UNHCR had just brought back from Thailand, were killed by a group of Khmer Rouge soldiers.

14 Although the Khmer Rouge leadership denied involvement in the murders, they tried to counteract the public relations blow by inviting Vieira de Mello back for a visit.

On September 30, 1992, he and Bos retraced the journey they had taken in April. The transformation since their last visit was staggering. An entire town had sprung up, as the Khmer Rouge had made good on their promise to give returning refugees land for rice cultivation and gardening. UNHCR had not yet assisted in the returns, but refugees had started finding their way to the area on their own.

In a meeting with General Ny Korn’s civilian representative, Vieira de Mello spelled out the contents of a “pragmatic package” he hoped the guerrillas could accept. “It has been six months since we were last here,” he told the official. “Many more refugees in the camps would like to come back, but we can’t give them assurances that they should do so unless you open up your territory.” Even if the Khmer Rouge continued to refuse to deal with Akashi at a political level, Vieira de Mello urged that the general allow unhindered access for UNHCR staff, for UNTAC de-miners, and for UN civilian police who would help ensure the safety of returnees. “Time is running out,” Vieira de Mello said.

15

The Khmer Rouge official nodded. “The door is open,” he said, adding, “if you come in, start doing something.” He asked for food, medical assistance, and diesel for bulldozers to improve the access road, but he said UN police were unnecessary because the Khmer Rouge would keep returnees safe. UNTAC de-miners would be allowed, but only those “of the right nationality.” Vieira de Mello understood this to mean the Thais, who were the longtime backers of the Khmer Rouge. He had an imperfect deal, but a deal at last.

16 “I know that they were using us,” he said later, “but we were using them too.”

17

The UN investigated the murder of the two returnees. In October 1992 Son Sen, the commander of the Khmer Rouge forces, wrote to Vieira de Mello denying responsibility. Instead of responding by presenting the UN’s evidence of Khmer Rouge guilt, Vieira de Mello wrote:

Excellency,

I have the honour to acknowledge receipt of your telegram dated 11 October in which you informed me that, according to your investigation, the [Khmer Rouge] was not involved in the alleged murders of two returnees that are said to have occurred in Siem Reap Province on 22 and 23 August. It proves that caution in the handling of and publicity on alleged incidents such as the one mentioned above, without a proper investigation having been conducted, is the correct approach.

Conversely, your message reinforces the request I made in my letter to you of 3 September, as repeated in my message of 16 September, that UNHCR/ UNTAC Repatriation Component, in particular, be granted access to the village in order to allow the investigation.

Yours sincerely,

Sergio Vieira de Mello

His unfailing politeness with the Khmer Rouge had earned him their respect—and at times it seemed even their affection. In 1992 Ieng Sary and Khieu Samphan sent Vieira de Mello identical New Year’s cards, each bearing a grainy photo of the remains of a majestic twelfth-century temple in Angkor Wat.

McNamara thought his friend was going too far. He believed it would be madness to place civilians back in the custody of mass murderers. At a minimum he believed the UN had a duty to advertise to the refugees the fact that they would be entrusting their fates to the same men who were responsible for two million deaths when they governed Cambodia from 1975 to 1978.

But Vieira de Mello plowed ahead. A November 1992 UNHCR leaflet distributed in Site 8 said nonchalantly: “UNHCR is about to start movements to some new areas where previously UNHCR had no access. Before deciding that it was safe to send you, UNHCR visited these areas a number of times.” The leaflet did not mention that the sites in question would be governed by the Khmer Rouge.

18 Reporters who journeyed to Khmer Rouge lands and spoke to returnees found widespread ignorance about the bloody past of local officials.

19 “We do not believe the stories about the Khmer Rouge genocide,” Eum Suem, a forty-three-year-old teacher who had spent seven years in a refugee camp, told the

New York Times.

20 Many, like Eum, had fled the Vietnamese invasion in 1978 and found it more chilling to entertain the idea of settling in land controlled by Hun Sen, whom they still saw as a Vietnamese puppet.

In January 1993 Vieira de Mello bucked the complaints of his peers, whom he wrote off as purists, and for the first time involved UNHCR in returning refugees to a Khmer Rouge-controlled area, known as Yeah Ath, or “Grandmother Ath.” On January 13, 1993, UNHCR helped 252 Cambodians in the Site 8 camp move to Yeah Ath, which he considered a pilot return village.

21 The Khmer Rouge managed to deliver unmined, fertile land, and the returnees used the UNHCR household kits to build houses, a pagoda, and a small school. UNHCR built a new access road, bridges, and seven wells. In the coming weeks some 2,714 Cambodians came directly from the border camps, while another 3,729 people made their way to Yeah Ath from other locations. “I do believe,” Vieira de Mello told an interviewer, “that Yeah Ath may be recognized in a few years as having been what I always had in mind: that is, a bridge—a very experimental, social bridge between the [Khmer Rouge] and the rest of the world.”

22

He defended the risks by citing Cambodian self-determination. “It is the choice of these people to come here, and we must respect that choice,” he told Philip Shenon of the

New York Times. When Shenon mentioned the savagery of the Khmer Rouge, Vieira de Mello snapped, “I don’t need anybody to tell me about that history. The Cambodians who are returning here are Ph.D.s in that history.”

23 But sometimes he did in fact make it sound as though he had lost sight of the bloodshed. After he left Cambodia, he would recall bringing journalists to Khmer Rouge lands so that “they could show to the world, to the international media that they were not the monsters that everybody believed they were.” Even though the monstrosity of the Khmer Rouge leadership had long been proven,Vieira de Mello simply did not keep it foremost in his mind.

He asked Lynch to base himself with the returnees in Yeah Ath so as to give UNHCR a pair of “eyes and ears” on the ground. Lynch agreed without hesitating. He made clear that Lynch should stay in Yeah Ath around the clock. “I don’t want to hear about you driving back to the Thai border to sleep,” Vieira de Mello said.

Initially Lynch had company, as Vieira de Mello had prevailed upon the Khmer Rouge authorities to allow an UNTAC civil police presence. But the American lawyer had watched in amusement as the UNTAC police attempted to set up shop in the inaccessible village. As a UN helicopter delivered a portable toilet, the wire snapped and the toilet tumbled into the Tonle Sap River. When the UN police tried to lower their housing containers into the area, the Khmer Rouge began shooting at them, and they fled in panic. Only later did they learn that the guerrillas had not been firing aggressively but had in fact been trying to alert the strangers that they were on the verge of making house in a minefield. Unsurprisingly, the UNTAC police did not last long in Yeah Ath. When Hun Sen’s forces attacked the village, the Fijian police voluntarily handed their vehicles to the Khmer Rouge, and soon packed up and left.

Even though reaching Yeah Ath posed enormous challenges, Vieira de Mello loved making the journey. He appreciated Lynch’s dedication. “I hear you’re living in a hammock,” he teased. “The returnees have already built houses for themselves, and look at the example you are setting!” Always one who prized languages, he urged Lynch, who already spoke Thai, to work on improving his Khmer. “All you do is sit under a tree,” he said playfully, “at least learn the damn language!” Lynch found it intensely annoying that, although Vieira de Mello knew only a few dozen words of Khmer, he pronounced them so flawlessly that Cambodians often mistook him for one of their own.

Vieira de Mello’s long-range radio call sign was TIN MINE, and he gave Lynch the moniker TIN MINE ONE. Months later Lynch inquired of his colleague Assadi about the origins of the strange moniker, and Assadi told him that it had nothing to do with Cambodia’s mining potential. Rather, it derived from Vieira de Mello’s favorite disco in Malaysia, which was called Tin Mine and which he remembered fondly from his days chairing the negotiations over the return of the Vietnamese boat people.

Vieira de Mello respected the risks that Lynch was taking by living on his own among the Khmer Rouge, but he did not cut the American any slack. Lynch had received two gifts from his Khmer Rouge hosts—the hammock and a pair of their light military boots. In presenting Lynch with the boots, the Khmer Rouge soldiers told him that if he stepped on a mine in the boots, he would lose a foot instead of an entire leg. Lynch, naturally, wore the boots everywhere. But Vieira de Mello spotted Lynch’s footwear on one of his visits. “What are you wearing?” he asked, enraged. “Take those off. You are here as an employee of the United Nations. Don’t you go native on me!” But his pique passed quickly. Several months later, when UNHCR rotated Lynch to Kenya, Vieira de Mello called Lynch’s boss in order to pay the highest compliment he could. “Put Jamie to good use,” he said. “He really knows how to work with thugs.”