Eight

“SERBIO”

The dark days in Bosnia were in fact far from over. Even though the NATO ultimatum had halted fighting around Sarajevo, the rest of the country remained at war. And the more determined Vieira de Mello became to defend the impotent UN mission, the more morally compromised he became.

He did not warm to his new post in Zagreb, Croatia. Although the Bosnian capital had been deadly dangerous, it had brimmed with life; Zagreb, with its large luxury hotels and visible sector of war profiteers, was hard to get used to. The tensions inherent in helping run a peacekeeping mission in a country not at peace had not abated. But what made matters worse was that he now had a “field job” away from the field. In a meeting with his new team on February 25, 1994, he told them that he looked forward to once-a-week staff meetings. A Canadian military lawyer raised her hand and said she would prefer it if the staff met three times per week. This was only a hint of the office atmosphere that would smother him in the coming months.

As the head of UNPROFOR’s civil affairs department, he inherited a slew of personnel who had been hired before his time and whom he couldn’t unload. He was quickly overwhelmed by the paperwork, the phone calls, the meetings, and the staff-management issues, and he asked Elisabeth Naucler, a Finnish lawyer, to become his chief of staff so that he could spend more time troubleshooting back in Bosnia. “The most difficult thing in a peacekeeping mission is the internal peacekeeping,” he told her. “His mind and heart were in Bosnia while his body was stuck in Zagreb dealing with staff infighting,” Naucler remembers. “It must have been torture.”

THE BLUFF THAT FAILED

But he soon got a reprieve from his desk job. Having escaped NATO bombing in the wake of the gruesome market massacre, Serb forces began attacking Bosnia’s eastern enclave of Gorazde in late March. Another of the six UNDECLARED “safe areas,” Gorazde was perched strategically on the main thruway connecting Belgrade and the Serb-held regions of Bosnia. Although the Gorazde enclave was quite large—it ran twelve miles from north to south and nineteen miles from west to east—only a handful of unarmed UN military observers and four UN aid workers were based there, which left its 65,000 inhabitants especially vulnerable. On April 6, the UN observers reported that the Serb offensive had left 67 people dead, including 10 children and 19 women and elderly men. Some 325 Bosnians had been injured. The food in the area would not last longer than two weeks.

1

That same day Vieira de Mello, who was visiting Sarajevo, set off with General Rose on a fact-finding trip to Gorazde. As the men entered Serb territory, they passed Serb trenches along the front line, and they saw an Orthodox priest in black robes giving communion to the soldiers. They got only as far as the Serb stronghold of Pale and were turned back. Vieira de Mello tried to convince the Bosnian Serb military commander Ratko Mladić that if the Serbs blocked passage, it would only prove their hostile designs. Mladić knew that the one thing few UN officials could resist was the promise of a cease-fire. He told the UN duo that if they returned to Sarajevo, he would negotiate a halt in fighting with the Bosnian army. True to form, the UN delegation agreed to return to the Bosnian capital. “If the Serbs say the situation is such that they don’t want us to go there now, we have to accept that,” Rose told the press.

2 Nonetheless, before returning to Sarajevo, Rose did persuade Mladić to allow a dozen mainly British elite officers to proceed to Gorazde to have a look around.

After his failed effort to reach Gorazde, Vieira de Mello took a preplanned trip back to Geneva and France. While he was away, the Serbs pressed ahead with their offensive, seizing a crucial 3,400-foot-high ridge overlooking Gorazde and setting fire to neighboring villages. U.S. intelligence, which had been monitoring the situation, intercepted a message from Mladić to one of his field commanders in which he said he did not want “a single lavatory left standing in the town.”

3Just two months after NATO had threatened to bomb the Bosnian Serbs around Sarajevo, the lives of Bosnians hung in the balance yet again. While in February the mere threat of force had caused the Serbs to pull back most of their weapons from around Sarajevo, in Gorazde it looked as though threats would not suffice; NATO would actually have to use air power if the Serbs were to be stopped. If Rose and Akashi did not call for help from NATO pilots, Gorazde and its large civilian populace looked certain to fall into Serb hands.

On April 10 General Rose did something few expected him to do: He summoned NATO bombers to give the peacekeepers he had sent into Gorazde “close air support.” Rose and Akashi had long said they were more comfortable with limited close air support (a defensive measure) than with air strikes (which they considered an act of war). And they believed a surgical defensive strike against Serbs firing on UN troops would deter the Serbs without squandering the momentum toward peace. Since the founding of NATO in 1949, the alliance had never before placed itself at the disposal of UN blue helmets. And it would not soon do so again. First Rose had to sign off on air request forms; then Akashi (who was in Paris) had to give political clearance; and finally NATO had to agree. By the time all three approvals had been received, more than an hour had passed. The cloud cover and rain were so thick that two NATO A-10 aircraft had to fly low through Bosnia’s valleys, which made them vulnerable to Serb ground fire. They were initially unable to find the offending Serb tanks and ran out of fuel. Two U.S. Air Force F-16C Fighting Falcons picked up where they left off, and at 6:26 p.m., two hours after Rose initiated the request, NATO struck, eliminating a Serb artillery command post four miles from town and reportedly killing nine Serb officers. This was the alliance’s first attack on a ground target in its history.

UN and NATO officials understood that a threshold had been crossed—for the UN, for NATO, and for Bosnia. The people of Gorazde were elated. They gathered in the streets and gave thumbs-up signs to the members of the small UN team encamped in the central bank building. Serbian president Slobodan Milošević predictably denounced the attack, which he said “heavily harms the reputation of the UN in its role as mediator of the peace process.”

4 By calling on NATO to bomb one faction, he said, UNPROFOR had taken sides. The following day, when the Serbs kept up their shelling, NATO struck again, destroying two Serb APCs and damaging one tank.

At his home in Massongy, France, Vieira de Mello was not where he wanted to be. After twenty-four years of service to the United Nations, he had happened to leave his mission area during one of the most important crises in UN history. Indeed, while NATO’s first-ever air operation was under way on April 10, he had the surreal experience of receiving a phone call from Charles Kirudja, Akashi’s chief of staff, who complained about personnel infighting in the office. Vieira de Mello rushed back to Zagreb on April 11, the day of the second strike, and found that the Serb offensive had not abated.

NATO’s sparing use of air power—critics quickly branded the two attacks “pin-pricks”—revealed just how constrained NATO was by UN concerns about retaliation against peacekeepers. It also showed the limits, in mountain areas, of the gleaming laser-guided technology that had seemed invincible in the Persian Gulf War. Western commentators noted that, with its tepid uses of force, NATO resembled the proverbial elephant that had given birth to a mouse.

5 On April 12 the Serbs raided three of seven weapons-collection points that had been established outside Sarajevo in February, taking back heavy weapons from a cantonment as a result of NATO’s ultimatum. By April 14, sensing that the UN and NATO were paralyzed, the Serbs had detained, placed under house arrest, or blocked the movement of 150 UN soldiers across Bosnia.

6 A

New York Times headline summed up the letdown: “THE BLUFF THAT FAILED; SERBS AROUND GORAZDE ARE UNDETERRED BY NATO’S POLICY OF LIMITED AIR STRIKES.”

7

Having pushed for air power to be used, President Clinton tried to claim that international forces remained neutral. “I would remind the Serbs that we have taken no action, none, through NATO and with the support of the UN, to try to win a military victory for their adversaries,” he said.

8 But Vieira de Mello saw that Clinton was trying to have it both ways: feeling good by standing up for the Bosnians but feeling safe by placating the Serbs. “This is Clinton’s ‘I didn’t inhale’ moment,” he told me at our first dinner meeting. “He wants to please everyone at once.”

At around 3 p.m. on April 15, the Bosnian defenses to the north and southeast of the town collapsed. The Serbs overran a UN observation post, pummeling a UN Land Rover north of Gorazde with machine-gun fire and seriously wounding two members of the elite squad of British officers that Rose had sent into Gorazde the previous week.

At just the time NATO might have struck back in retaliation for the attack on the British soldiers, Akashi was in the midst of a seven-hour meeting with Karadžić in his Pale headquarters.

9 John Almstrom, Akashi’s Canadian military adviser, set up the secure satellite phone to NATO in the parking lot and carried the military maps of potential targets in his briefcase. “This was a bad dream,” recalls Almstrom. “You are in Karadžić’s office and you know you are probably going to bomb Karadžić.” But unsurprisingly Akashi chose not to do so, opting instead to work with the Serbs to evacuate the wounded British soldiers.

Vieira de Mello had seen UN resolutions and observation posts trampled in Lebanon, but this time around he was the second-highest-ranking political official in the mission, beneath only Akashi. He could try to use his clout to alter UNPROFOR’s course. But as he confessed to me that evening, he did not see a way out.

The following day, with the Serbs continuing their stampede toward Gorazde, Rose called for NATO air power for a third time, but on this occasion, in order to avoid inflaming Serb tempers, he informed Mladić that he had done so. At the sight of NATO planes, the forewarned Serb tanks shot down a British Sea Harrier with a shoulder-fired missile. Even though the pilot safely ejected and reunited with Rose’s men in Gorazde, this was the first time in NATO history that it had ever lost a plane in a combat operation, and Admiral Leighton Smith, the American who commanded NATO forces, was furious. Smith said he was fed up with the restrictive rules of engagement insisted upon by Akashi and Rose. The tactical constraints and the UN’s advance warnings to the Serbs were endangering his pilots.

Inside the UN safe area Bosnian military resistance had evaporated, and artillery rounds were falling in the town once every twenty seconds.

10 In Washington, U.S. national security adviser Anthony Lake said that the possibility of saving Gorazde was “very limited.”

11 Back in New York the Bosnian representative to the UN, Muhamed Sacirbey, released a statement that said that the UN, the “most noble of institutions,” had been “usurped into a chamber of false promises and rationalizations for inaction.”

12

No matter how aggressive the Serbs became,Vieira de Mello clung to the belief that full-on NATO air strikes were not compatible with UN neutrality, and that UN neutrality was the cornerstone of the UN system. He did what he could to defend UNPROFOR’s dwindling reputation. In Zagreb he met with a delegation of Bosnian government officials who slammed the UN. He explained that UN Security Council Resolution 836, which created the six safe areas, had been “badly drafted” by the Council, “probably on purpose.” But he spoke as though he lacked free will of his own. Since he and the peacekeepers had been told they could use military force only in self-defense, they were not to blame for their passivity. It never seemed to dawn on him that he might help shape the views of governments from within the system. Perhaps knowing that he was shirking responsibility and uncomfortable in doing so, he lashed out, repeating Serb accusations that the Bosnians kept weapons in the safe areas and adding, in an uncharacteristically hectoring tone, “You know it is true!” At the end of the meeting Bosnia’s secretary for foreign affairs, Esad Suljić, issued a prophecy: If the UN did not step up immediately to protect Bosnians in Gorazde, the Serbs would attack the two other nearby safe areas. “Srebrenica and Zepa will be next,” the Bosnian official said.

13

While the Bosnians were desperate, the Serbs were flush with confidence. In Belgrade they stripped CNN, AFP, SKY,

Le Monde, Die Presse, Radio Free Europe, and the

Christian Science Monitor of their media accreditation.

14 Outside Sarajevo they overran a UN weapons-collection site under French guard and seized an additional eighteen antiaircraft guns. They fired four shells at the central bank in Gorazde, where UN officials slept and worked. The strike knocked out the UN telex system that the small UN team was using to file their reports.

15

With the safe area seemingly written off, an Irish UNHCR doctor named Mary McLaughlin wrote a letter to UNHCR headquarters in Geneva that was leaked to the press. It read in part:

Greetings from a city where only the dead are lucky. The last two days here are a living hell. Both residents and refugees have crowded into crumbling buildings, waiting for the next shell. When it hits, many are killed, as there are such crowds in each building.

The wounded lie for hours in the debris, as it is suicidal to try and bring them to the hospital. . . . The Serb excuse for targeting [the hospital] is that it is a military institution. I’ve been in all parts of the hospital 100 times in the last month and can assure the outside world that it’s a lie.

... Presidents Clinton and Yeltsin want to hold talks about the future of Bosnia next month. There will be little left in Gorazde by then but corpses and rubble.

16

Aid workers and peacekeepers throughout Bosnia understood that they were at a turning point. “Clearly it is a very sad week for the world,” Rose admitted to the press.

17“THESE GUYS HAVE BALLS”

But just when all appeared lost, the United States and Russia conspired to preserve what was left of the Gorazde enclave. In the United States public criticism of the Clinton administration had been fierce. It was not merely civilians in Gorazde who were at stake. NATO, which had acted for the first time in its history, had suffered a major blow to its prestige. At a White House press conference President Clinton felt he had no choice but to ratchet up the threat of NATO air power.

But U.S. threats alone carried little clout. Luckily for Gorazde, Vitaly Churkin, Russia’s envoy in the region, turned on the Serbs. He had spent a week shuttling between Pale and Belgrade and was fed up: “I have heard more broken promises in the past 48 hours [than] I have heard probably in the rest of my life.” Upon returning to Moscow, he was even more emphatic. “The time for talking is over,” he said. “The Bosnian Serbs must understand that by dealing with Russia, they are dealing with a great power and not a banana republic.”

18 On April 19 President Yeltsin called on the Serbs to fulfill the promises they made to Russia. “Stop the attacks,” he said. “Withdraw from Gorazde.”

19 “Our professional patriots always talk about ‘special relations with Serbia,’ ” an editorial in the Russian newspaper

Izvestia said. “What does that mean? Approval of everything the Serbs do, even if they commit a crime?”

20 Vieira de Mello saw Russia’s shift as a diplomatic breakthrough. “At last, perhaps, it will not be divided nations attempting to make peace,” he told me, “but the

United Nations.” With Russia now standing behind NATO’s hard-line condemnations, the Serbs would no longer be able to play the major powers off one another.

On April 22 the sixteen Western ambassadors to NATO issued an ultimatum in Brussels meant to rescue Gorazde. The Serbs were told that they had to cease firing around Gorazde immediately. By one minute after midnight GMT (2:01 a.m. Bosnia time) on April 24, Serb troops had to withdraw to two miles outside the town center and allow UN peacekeepers, relief convoys, and medical teams to enter. And by one minute after midnight GMT on April 27, they had to pull their heavy weapons (including tanks, artillery pieces, mortars, rocket launchers, missiles, and antiaircraft weapons) out of a twelve-mile exclusion zone similar to that which had been established around Sarajevo. If the Serbs did not comply with these terms, they would be bombed, and this time the air attacks would leave no doubt about NATO’s seriousness. NATO pilots no longer had to find the offending weapons; they would be unleashed to strike at a range of military targets. NATO generals said they had picked out two dozen ammunition sites, fuel dumps, command bunkers, and gun posts around the area. Washington withdrew nonessential personnel and diplomats’ families from Belgrade. “The plan is to bomb the crap out of them,” one NATO official said.

21Because the UN still had peacekeepers on the ground, however, NATO would still not be able to bomb without getting the request from Rose and Akashi, who continued to worry about crossing the “Mogadishu line” and jeopardizing the safety of peacekeepers. Vieira de Mello and Akashi received permission from the Serbs to travel to Belgrade, where they hoped to negotiate a way out with—and for—Karadžić and Mladić. The UN officials preferred agreements to ultimatums, and irrespective of any NATO threats, they remained convinced that they could talk the Serbs out of taking Gorazde.

At the talks in Belgrade, the same day as the ultimatum, the UN delegation lined up on one side of the table, the Bosnian Serbs took seats opposite them, and Serbian president Slobodan Milošević, who was thought to be responsible for the war, served as the chair. On one occasion when General Mladić spoke up, Milošević snapped at him in English. “Will you shut the fuck up?!” Milošević’s every gesture and statement seemed designed to show the UN who was boss but also to create the illusion that he was estranged from the field commander known to be bombarding Gorazde’s civilians. Instead of repenting, the Bosnian Serbs were more brazen than ever. Since NATO had carried out two air strikes, Karadžić said, “it will take us time to trust the UN again.” When Akashi said he understood, his aide Izumi Nakamitsu passed a note to her colleague David Harland, saying, “This makes me sick.”

Toward the end of the Serb-UN negotiations, which lasted from 1 p.m. to the late evening, Akashi asked how the UN might verify Serb compliance. Suddenly the Bosnian Serb vice president Nikola Koljevic spoke up: “Why doesn’t Sergio go to Gorazde?” Vieira de Mello leaped to agree. “Sure,” he said, “I’ll go.” The rest of the UN team was stunned. “It happened so fast and it was so last minute that we didn’t see it coming,” Almstrom, Akashi’s military adviser, recalls. “I used to call him ‘Sergio the gunfighter,’ but this was ridiculous. I thought either he’s got huge courage or he doesn’t realize the implications of this. What if the Serbs don’t pull their weapons back? Or what if they do and NATO bombs anyway?” The Serbs had a more cunning agenda. If Vieira de Mello led a UN team into Gorazde, NATO countries would be even more reluctant to bomb. Milošević adjourned the meeting with the deal nearly finalized. He urged both sides to shore up the remaining details in the morning. Delays were costly, the Serb leader said insincerely, “while people are dying.”

22

As the UN officials staggered out of the negotiations, Almstrom asked, “Sergio, what if the ultimatum fails and you get bombed?” Vieira de Mello shrugged. “The United Nations will just have to make sure the ultimatum doesn’t fail, won’t we?” Rose was thrilled when he learned that his friend would be the one with his finger on the UN trigger. He lent him a sleeping bag and a pair of British army boots for the trip.

23 In a classic testament to the lack of synchronization between UNPROFOR and NATO, the UN’s agreement with the Serbs was drafted using local time, creating a two-hour time difference between it and the deadlines in the NATO ultimatum, which were issued in Greenwich mean time.

Remarkably, at the very time the Belgrade negotiations were under way, the Serbs had gone right on shelling Gorazde. A UN observer wrote from Gorazde: “Team leader’s assessment: These guys have balls.” The UN team had recorded fifty-five shell explosions in Gorazde in one ten-minute period. “They have blatantly increased their aggressive activities in the face of the NATO ultimatum,” the UN observer noted.

24 Major Pat Stogran, the thirty-six-year-old head of the UN military observer team in Gorazde, sent several consecutive panicked messages to headquarters and heard nothing back. He finally threatened to stop sending reports. “If you had any idea of the situation on the ground here you would understand the futility of the messages that we are sending off into the dark expanse,” he wrote. “It is embarrassing that I, as the senior representative of UNPROFOR, cannot advise the local civilian and military authorities of the activities of UNPROFOR except that which we glean from BBC.”

25

More than twenty people in Gorazde would be killed the day of Vieira de Mello’s trip to Belgrade.

26BREAKING THE SIEGE, BLOCKING AIR STRIKES

Critics pounced on the UN deal.Vieira de Mello’s verification team seemed to be walking into a trap with their eyes open, as if they were willfully placing themselves in harm’s way in order to supply the Serbs with potential hostages and foil any potential NATO attack. He ignored the grumblings and focused on the task he had been assigned. From the airport in Belgrade, he telephoned UNPROFOR headquarters in Zagreb and put out the word that he was looking for UN volunteers. When he received phone calls back, he did not try to sugarcoat the mission. “I warn you,” he told interested staff, “you might end up trapped in Gorazde or NATO might bomb.” He flew to Zagreb for a few hours in order to pack, then flew to Sarajevo, where he stopped into the Bosnian Presidency to explain the mission to Prime Minister Silajdžić, who had broken off contact with Akashi and Rose. “You know that by going you are ensuring NATO does not use force again?” Silajdžić said. Vieira de Mello did not respond. “Good luck anyway, my friend,” Silajdžić said. “Be careful.”

Around 8 p.m. on Saturday, April 23,Vieira de Mello met up with a large UN convoy at Sarajevo airport. The convoy included 40 medical personnel, 100 Ukrainians who reported to a French general, and 15 political officers and civilian police who reported to him. Anthony Banbury, who had been with the UN in Cambodia, had arrived in Bosnia earlier in the month. When he heard that Vieira de Mello had issued the call for volunteers, he made his way to the snowy airport in hopes of earning a spot on the team. Banbury walked to the lead vehicle in the convoy, where Vieira de Mello was seated with his French bodyguard, and tapped on the glass of the armored personnel carrier. The French soldier opened the door and raised his machine gun as a barrier to keep Banbury away. “It’s okay, it’s okay,” Vieira de Mello said, smiling broadly at the young American, whom he had not seen since Cambodia. “Tony, what are you doing here?!” Although he had been impatient to depart, he stepped out of his vehicle and inquired about Banbury’s recent posting in Haiti and his plans with UNPROFOR. “There we were in the dark, at the Sarajevo airport with gunfire going off in the background, the UN mission crumbling, and the NATO threat of air strikes hanging over us,” recalls Banbury. “And Sergio calmly emerged from the armored personnel carrier and made me feel, for those few minutes, like nothing in the world was more important than me.” Vieira de Mello instructed the French soldier to make room for Banbury in one of the vehicles, and the convoy set off in the dark.

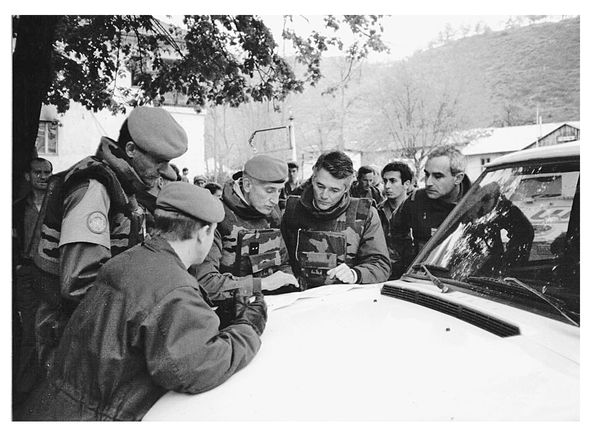

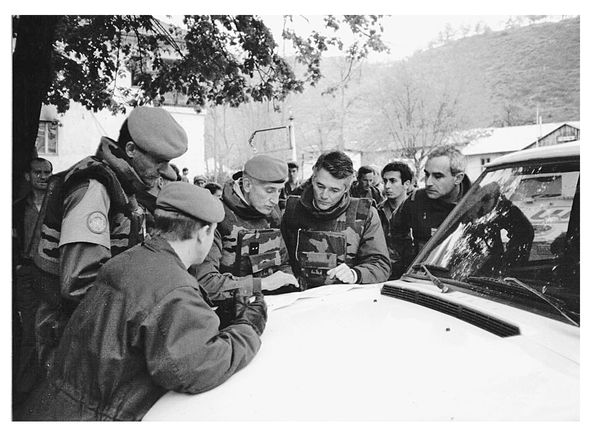

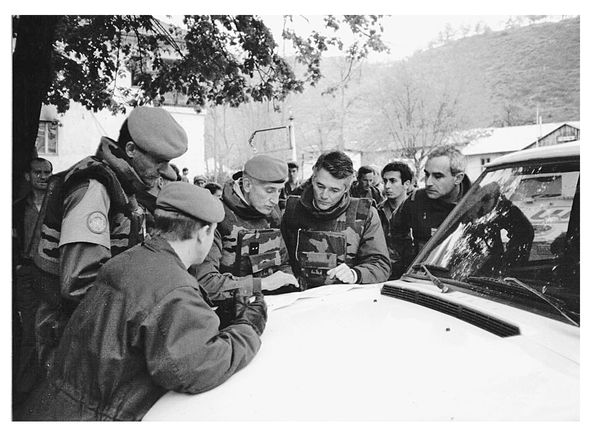

Vieira de Mello and UN General André Soubirou planning to enter Gorazde.

They arrived on the outskirts of Gorazde just after midnight. Vieira de Mello saw houses still burning, dead animals on the roadside, and crowds of refugees crammed into the roofless hulks of charred houses. He drove into town and headed to the central bank, where he found Stogran and the other UN observers looking exhausted and unshaven. “The only food left here is what is left of UNHCR rations,” the Canadian told him.

The next morning, Vieira de Mello gathered his small political team for a morning meeting. Groggy UN officials found their boss looking meticulously groomed. “What did you do?” Banbury asked. “Pack a shower in your suitcase?” “If we look our best,” he replied, “we will remind people here of the dignity they used to have. And we will show them that the siege has been broken.” When Mark Baskin, a forty-one-year-old American, asked, “What should we do?” Vieira de Mello answered, “Walk around.” “Walk around for what?” Baskin asked. “Show the flag,” Vieira de Mello said. “Then the people will know that the UN has come to town.”

Although the shooting had largely stopped, team members saw bullet casings, shrapnel, pockmarks, and bloodstains on the buildings. Vieira de Mello was determined to make the UN as visible as possible, and he was intrepid in that pursuit. Surrounded by UNPROFOR soldiers decked out in helmets and Kevlar, he strode around town in slacks and a winter parka, crossing the downtown bridge that had been the scene of fierce battles. The sound of gunfire and the presence of Serb militiamen hardly seemed to register with him. “We were completely surrounded,” recalls Nick Costello, a Serbian-speaking British UN officer. “We were vulnerable from all the high ground, and as we drove around in our shiny white vehicles, we made ripe targets.” Vieira de Mello’s nonchalance was strategic. “Normalcy is returning to Gorazde,” he told his aides. “If we show the people that we are not afraid, we can ease their own fears. If we act as though life is normal, life will become more normal.”

Stogran, who had felt ignored by his UN superiors when it mattered, was suddenly overwhelmed by UN officials who had not suffered through the siege and yet who now overran his team’s meager resources. He had used diesel containers to store water from the local river in case of emergencies, but he found the newcomers unthinkingly pouring the river water into the generator, believing it was fuel. “This is classic UN,” Vieira de Mello said to Stogran, acknowledging the strain he must have felt. “So many chefs, we can’t even find the kitchen!”

Stogran found the self-styled “UN saviors” uncurious about the past and sanctimonious about how the Serbs and Bosnians could be brought into line in the future. Though they had never set foot in Gorazde before, they had their maps and their preexisting assumptions and asked few questions. But Vieira de Mello was different. “You were the voice of this place,” he told Stogran. “You made it far harder for the politicians to look away.” The beleaguered major was touched. “After every conversation with Sergio,” he recalls, “I walked away feeling a deep and totally novel sense of calm.”

At around 5 p.m. on Vieira de Mello’s first full day in Gorazde, the Serbs began to leave the town in accordance with the ultimatum. But as they retreated, they adopted a scorched-earth policy, blowing up houses and the sole water-pumping station in the area. Vieira de Mello was incensed. “This was the most outraged I had ever seen him,” recalls Costello. “He was full of passion, his voice was trembling, but at the same time he was trying to maintain his charm with the Serbs.”

At midnight he and Costello drove in their Land Rover to a village called Kopaci on the outskirts of town. The Serbs were blocking the entry of a second UN supply convoy, and he hoped to negotiate its release. A line of UNHCR relief trucks stood stalled roadside, while the surrounding hills blazed with fire. Suddenly, in the headlights, he spotted the burly figure of General Mladić, who was yelling about the desecration of the town’s old Serbian Orthodox church. When Mladić saw him, he seemed pleased and beckoned him. Mladić used Costello’s flashlight to steer them to the grave-yard behind the church, where he directed Vieira de Mello’s attention to the smashed headstones and to the freshly dug graves of Serb soldiers who had died in recent fighting. Vieira de Mello, who was not entirely comfortable being led into the pitch black by this suspected war criminal, noticed that Mladić was weeping. “Don’t ever forget what you have seen here,” Mladić said. He shook Vieira de Mello’s hand and said he would at last allow the stalled UN relief convoy to proceed into Gorazde. It was 2 a.m.

27

Vieira de Mello did not have a big enough team or enough time to thoroughly certify whether the Serbs had withdrawn all their heavy weapons from the twelve-mile exclusion zone. As he told the press, “In these hills and forests, we don’t have the means to tell you they are clear.”

28 But this was somewhat disingenuous. He knew that he did not want to see NATO air strikes, and as the person who would determine whether the Serbs were in violation of NATO’s terms, he had the power to prevent them. Costello remembers the exchange that preceded Vieira de Mello’s final communication with Akashi before he announced his verdict: “Sergio asked us, nudge nudge, wink wink, ‘Have you verified the weapons are out of the exclusion zone?’ and we said, ‘Yes, we have.’ We lied to NATO,” recalls Costello. “We knew NATO was itching to do air strikes and we knew it would have been the wrong thing to do. We physically couldn’t check all the sites—we had run out of time—but we also knew that confirming Serb compliance was what was best for everyone.”

Vieira de Mello even compromised on the two-mile area in the center of town that was meant to be free of soldiers. As early as April 25 Serb militia were found there. The Serbs said these police had remained so as to protect Serb civilians, but the “policemen” were obviously soldiers who had just changed from green army to blue police uniforms.Vieira de Mello opted to let the matter rest.

On April 27 Akashi declared publicly that the Serbs were in “effective compliance” with the ultimatum. Thus, for a second time in two months, he announced that he would not call for NATO air power.

29

The Bosnians were crushed, as they knew that their only lasting reprieve would come if NATO stopped the Serbs militarily, and UNPROFOR seemed intent on preventing that from happening. But Vieira de Mello made the implausible claim that he had acted in accordance with the will of the Bosnian people. “I was in Gorazde. I spoke with the inhabitants,” he told a Croatian journalist. “The majority of them agreed with me, because if we had struck from the air, they would have been worse off.”

30MUDDLING ALONG

Although Vieira de Mello had spent only four days in Gorazde, he returned to Zagreb with a new mystique. Izumi Nakamitsu, Akashi’s special assistant, saw him back at headquarters and inquired, “Weren’t you frightened about being bombed?” He smiled. “Izumi, please, you know they would never bomb while I was there.” Most people recalled his grace under pressure. The tales of his brushing his teeth with Italian mineral water fed his increasingly hallowed persona.

Akashi contentedly took credit for the apparent calming of tensions. He responded to a congratulatory message from Secretary-General Boutros-Ghali with a letter of his own:

Mr. Secretary-General,

I am touched by your kind message. I am proud that UNPROFOR has again proved its ability to control a dangerous situation. Under your wise guidance I will continue to serve the cause of our Organization by combining firmness with flexibility and by harnessing power with diplomacy.

Kindest regards,

But flush with confidence, Akashi then sparked a minidrama at UN Headquarters in New York, causing already substantial fissures between the United States and the UN to widen. Washington, the UN’s largest funder, had always been hard on the organization for its financial laxity. But as the isolationist wing of the Republican Party gained strength in the post-cold war world, some members of Congress had started calling for outright withdrawal from the UN, and both Republicans and Democrats had begun invoking UN peacekeeping failures in Somalia and Bosnia as grounds for cutting off vital U.S. funds. The normally reserved Akashi gave an interview to the

New York Times in which he suggested that since Somalia, the United States had lost its nerve, becoming “somewhat reticent, somewhat afraid, timid and tentative,” avoiding putting its own troops where they were needed to help in “situations like Gorazde.”

32 Akashi, who was himself extremely timid, wanted U.S. troops on the ground because he felt U.S. officials would then share his opposition to using air power. But Madeleine Albright, the U.S. ambassador to the UN, lit into Akashi, calling it “totally counterproductive for an international civil servant to be criticizing any government” and adding that UN officials “should remember where their salaries are paid.” Appearing before the UN Security Council, Albright warned, “Statements such as these cannot help but call into question the utility of further U.S. contributions, financial or otherwise, to UN peacekeeping. It is no secret that at present UN peacekeeping is not popular among either the American people or the U.S. Congress.”

33While Akashi’s statement had been manifestly accurate, Albright’s rebuttal made it clear who buttered Akashi’s bread. There was simply no way, structurally, that a senior official in the UN could get away with publicly criticizing the wealthiest and most powerful country in the organization.

And the hole Akashi was digging for himself grew deeper. In early May he crossed a line that stunned even his harshest critics: He instructed UNPROFOR peacekeepers to escort Serb tanks through the heavy weapons exclusion zone ringing Sarajevo, effectively using blue helmets to shield offensive weapons that were being transferred for use at another battlefront. Vieira de Mello could not believe his ears when he received news of Akashi’s blunder. “Here was Sergio, who spent hours every day cultivating these relationships, and finessing these incredibly intricate deals, and suddenly Akashi offers to help the Serbs move their weapons,” recalls Simon Shadbolt, Rose’s military assistant. “He was horrified.” So was Prime Minister Silajdžić, who declared, “Whatever credibility the UN and the international community had has been ruined . . . by the behavior of UN representatives here.”

34 U.S. Senate minority leader Bob Dole called for Akashi’s resignation. “Akashi’s approach is one of appeasement,” Dole said in a statement:

He meets with war criminals and calls them friends. And when the United States refuses to send soldiers under UN command, he calls us timid. Akashi should be sent packing to a post far away where his weakness and indecisive-ness will not cost lives . . . UN officials speak of the need for neutrality as though they are referees in a sports match. The problem is that this game is aggression.

35

When I saw Vieira de Mello in Zagreb and asked him what he thought of what became known as “tank-gate,” he was unwilling as ever to break ranks. He went as far as he could, answering, “Not ideal.”

With Akashi discredited,Vieira de Mello became the only senior UN official whom the Bosnian government would see. Although he had supported the approach taken by Akashi and Rose, he somehow escaped criticism. “He was a man first, a UN official second,” explains Silajdžić. “He always made us feel he understood our point of view and was brainstorming constantly to help us get what we needed. He didn’t hide behind the usual UN excuses.” Although Gorazde was no longer being shelled, the enclave was still racked by violence. UN troops were being shot at by both sides, and Serb troops returned inside the two-mile zone. “It is tense,” Mark Baskin, the UN political officer, wrote from Gorazde. “We seek direction.”

36

Vieira de Mello felt as though he had little to offer. UN peacekeepers were back in a situation much like that in southern Lebanon, where they had been bossed about by Israeli troops and their Christian proxies. Just as he had done then for General Callaghan, he drafted letters of protest on his boss’s behalf. As then, he could only warn Karadžić that if he didn’t remove Serb gunmen from Gorazde, “I shall have no alternative but to report to the Secretary-General of the United Nations and, through him, to the Security Council.”

37 The Serbs knew that they could do as they pleased. A Karadžić aide wrote back mischievously that the armed Serbs in the Gorazde exclusion zone were not in fact soldiers—they just could not find “anything to wear” other than uniforms.

38 Vieira de Mello knew that the UN could not keep traveling to the brink and back. “We must get away from this succession of exclusion zones, violations, cease-fires which go nowhere,” he told reporters at a press conference. “We need a political solution.”

39

He wondered if a Cyprus-like stalemate was the best that the former Yugoslavia could hope for. At a May 10 meeting with a delegation of potential donors, he exclaimed dogmatically that in the Balkans “hatred is the bottom line!”

40 He saw that the UN brand could end up permanently soiled if it remained implicated in a mission that was no more achievable than Somalia had been. The countries on the Security Council that had sent the peacekeepers to Bosnia with an ambiguous mandate and insufficient means were the ones letting the Bosnians down. But it was the “UN,” and not the responsible individual governments, that would take the blame. “Americans are justifiably wary about putting troops at the United Nations’ disposal,” said a

New York Times editorial. “UN troops in Bosnia are empowered to do little more than flash their blue berets and count the Serb shells obliterating Gorazde.” The editorial hailed a new U.S. presidential directive that placed strict limits on U.S. funding and participation in UN peacekeeping missions.

41

When Rose first arrived in Bosnia, he had been eager to push the boundaries of the UN mandate. But he had grown similarly resigned. “The guns could be heading for their next offensive,” he said. “If somebody wants to fight a war here, a peacekeeping force cannot stop it.”

42 Under his command UNPROFOR would not call in NATO air strikes to protect civilians. “We took peacekeeping as far as it could go,” Rose said. “We took it right to the line.”

43 The Serbs, who carefully tracked all international statements, took heed. With no threat of NATO air power hanging overhead, the Serbs treated UNPROFOR as a nuisance that they could manipulate or ignore.

While Vieira de Mello had hoped to use humanitarian achievements to bring about political change, by the late summer of 1994 it was clear that international heavyweights like the United States, Russia, and Europe would have to step up their commitments if they were to negotiate a peace to save civilians. UNPROFOR was increasingly unable even to deliver food to hungry civilians. In July the Serbs suspended UN aid convoys into Sarajevo. On July 20, after several UN planes were hit by Serb gunfire, the UN stopped sending in relief by air. And on July 27 Bosnian Serb leader Karadžić sent a letter to UN authorities announcing the closure of Vieira de Mello’s precious Blue Routes, which had done so much to restore life in the Bosnian capital. Some 160,000 civilians and 32,000 vehicles had made use of the open roads.

44 But after a four-month reprieve, the Serbs were strangling Sarajevo once again. What Vieira de Mello did not seem to recognize was that by covering up Serb violations rather than appealing to Western countries for sustained help, UNPROFOR was actually reducing the odds of a stronger Western stand. He, Akashi, and Rose were making it easier for powerful governments to look away.

He plodded ahead, attempting to negotiate a large prisoner exchange. Bosnian vice president Ejup Ganic asked how Vieira de Mello could trust the Serbs to free prisoners when in the previous two months they had deported some two thousand elderly Bosnians from the town of Bjeljina. “I appreciate Mr. Vieira de Mello’s optimism,” Ganic said at a press conference. “But for God’s sake, they are expelling thousands of people from their homes, putting them into labour and concentration camps.”

45 Vieira de Mello relayed the statements made by Bosnian Serb leader Karadžić as if they were reliable. “[Karadžić] assured us this was not his policy, that this was obviously contrary to the interests and the reputation of the Bosnian Serbs and that he was taking every possible measure, including the replacement of the police chief of Bjeljina, so as to bring these practices to an end,” he said credulously.

46 The longer he remained a part of the flawed UNPROFOR mission, the more he sounded as though he had stopped seeing the facts as they were. For the first time in his career, he seemed to be valuing the UN’s interest in looking good over civilians’ interest in being safe.

He had been a consistent supporter of the nascent UN war crimes tribunal that had been set up in The Hague in 1993 to punish crimes carried out in the former Yugoslavia. Even if he was willing to “black box” the brutal deeds of suspected war criminals in his negotiations, he believed it was important that the UN system as a whole find a way to punish the perpetrators of atrocity. He had argued this position over Akashi’s objections. Yet by the fall of 1994 he was so dispirited that he started contradicting his own beliefs. He sat down with the Washington Post’s John Pomfret and discussed the role that grievances from the Second World War were playing in fueling the Balkan crisis. “These people should just forget,” he said sharply. He compared the military rule in Argentina with that in Brazil and argued that the reason Brazil had managed to move on, while Argentina still seemed mired in recriminations over its past, was that Brazilians had decided to let go of their pain. Pomfret challenged him, arguing that it was precisely the failure to reckon with previous crimes that had made it easier for Serb extremists to rally their people to pursue long-sought revenge. This time around, when the wars ended, some form of accountability for the atrocities and some attempt at closure were essential.Vieira de Mello said he disagreed, calling the idea “very American.” When Pomfret, a China expert, said that in fact he had learned these lessons in China, where the crimes of the Great Leap Forward and Cultural Revolution had been covered up at considerable cost, Vieira de Mello shook his head. “China is on the right track,” he argued. “Remembering history will only slow them down.”

In September he traveled to Pale to attempt to defuse tensions between UNPROFOR and the Serbs. When Karadžić lectured him about the UN’s “intolerable” pro-Muslim bias, he said he understood the Serbs’ bitterness but rejected their allegations. “The UN

is impartial,” he said. “Our efforts to seek peace in the Balkans are benefiting all sides equally.” And then to underscore the point he admitted, “NATO intervention might have been far more serious if not for UNPROFOR’s restraint.” Karadžić knew this to be true, but he countered that “UNPROFOR’s presence had prevented the total defeat of the Muslims.”

47 Here Karadžić too was correct.

Despite the mounting indications that he and UNPROFOR were addressing symptoms and not causes, Vieira de Mello kept his focus on tactical humanitarian gains. He began his final negotiations on prisoner exchanges on September 30, 1994. The talks began in the morning, and the parties spent the entire day feuding. As the discussions dragged on past midnight, French UN officials began serving whiskey and plum brandy. Several people drank so much that they passed out in their chairs. Vieira de Mello, who was returning to UNHCR in Geneva the following week, would not be denied. As dawn broke, after twenty hours of negotiation, the Bosnians and the Serbs settled on the terms of the lengthy agreement, which would allow for the release of more than three hundred prisoners. All that was left was for him to add his official signature.

However, when Darko Mocibob, a Bosnian UN official, began translating the annexes to the agreement, Vieira de Mello realized that, during the bathroom breaks, the parties had struck a number of side deals benefiting their friends and families. As Mocibob translated the handwritten side texts, he watched a frown come over his boss’s face. “I could hardly suppress my laughter as I read him the additional terms, which none of us had expected,” Mocibob recalls. “It was ‘when Mehmed is released to the other side, he can carry 400 deutsch marks and 5 kilos of tobacco. Milos will be allowed to bring his pistol. And all the returnees will all be able to carry shoe glue.’” Vieira de Mello was desperate to close the deal, but not at the expense of the UN’s prestige. He refused to affix his signature to the private bargains. “I’m very happy for you that you have reached this agreement,” he said, too tired to be amused. “But you’ll have to find somebody else to be a witness. I am a senior official with the United Nations.” Only when the parties removed their side annexes did he agree to sign.

The UNPROFOR mission was neither effective nor respected. Vieira de Mello had been away from UNHCR for a year and was due back. In one of his final interviews, he said he was leaving the region with a “bitter taste in my mouth.”

48 Yet while he would not miss the humiliations, he would miss the people, the drama, and the global stakes. At a farewell reception at UN headquarters in Zagreb, his colleagues presented him with a parting gift of a framed photograph of the trams running along Sniper’s Alley in Sarajevo, with children running nearby. One UN official joked, “Just think, Sergio, one of those children might be yours.” Vieira de Mello smiled politely, but as Elisabeth Naucler, his Finnish aide, recalls, “He could have done without it.”

He conducted a mini-farewell tour of the former Yugoslavia. In Zagreb he bade a stiff farewell to Croatian president Franjo Tudjman, whom he had never liked. In Belgrade he pounded the pavement of the old city, looking for a gift for Serbian president Slobodan Milošević. In the end he settled on a painting, which he presented at a warm final meeting in the Presidential Palace in downtown Belgrade. In Sarajevo, the city that had stolen his heart, he said good-bye to President Izetbegović, and Prime Minister Silajdžić, whom he now considered a close friend.

What was most remarkable about his departure was that each of the feuding factions had come to believe he was their ally. “How many UN officials do you think would be sent off like that by all sides?” asks Vladislav Guerassev, who headed the UN office in Belgrade. “It shows you what a remarkable diplomat he was.” But during a bloody and morally fraught conflict in which the Serb side committed the bulk of the atrocities, his popularity with wrongdoers stemmed in part from his moral relativism. Even though he was unfailingly kind to Bosnian individuals, he had lost sight of the big picture. He seemed more interested in being liked and in maintaining access than in standing up for those who were suffering. He had brought a traditional approach to peacekeeping to a radically novel set of circumstances. And uncharacteristically, he had failed to adapt. Although Vieira de Mello was unaware of it, his seeming eagerness to side with strength had caused some of his critical UN colleagues to nickname him “Serbio.” It would take a massacre in another of the UN’s “safe areas” to jolt him into the belated recognition that impartial peacekeeping between two unequal sides was its own form of side-taking.