Sixteen

“A NEW SERGIO”

If Vieira de Mello revealed an important quality in East Timor, it was not his wisdom so much as his adaptability. As early as the spring of 2000 he felt that his mission, which was seen outside of East Timor as a rare UN success, was on the brink of failure. Physical security was breaking down, the economy was in ruins, and the Timorese had begun to view the UN as a second “occupier.” Desperate to recover, he aggressively cracked down on security threats and attempted to give the Timorese a meaningful say in their own affairs. In order to regain momentum, he realized, he would have to pay more attention to Timorese dignity and welfare than to UN rules.

PROVIDING SECURITY FIRST

The greatest fear of the Timorese was that the Indonesian militias would return. While they resented the UN political footprint, they valued the UN military presence. When the peacekeeping troops took over from the Multinational Force, Vieira de Mello made clear there would be no letup in security. The UN force, he warned, would “maintain the highest deterrence and reaction capacity in East Timor, which I would not advise anyone [to] test.”

1 Rumors still swirled that the pro-Indonesian militia planned to come back to massacre the population. On July 24, 2000, Private Leonard Manning, a twenty-four-year-old blue helmet from New Zealand, became the first battle casualty of the peacekeeping force when he was shot in the head while out on patrol near the town of Suai, on the border with West Timor. When his body was recovered several hours later, his throat had been slashed and his ears cut off.

2The day of the attack Alain Chergui, one of Vieira de Mello’s bodyguards, drove to his boss’s house. When he arrived at the door, Vieira de Mello skipped his usual pleasantries and said simply, “We are going to Suai.” Chergui recalls the transformation. “His face was so serious, so heavy, dour,” the French protection officer remembers. “He was not like Sergio.” When they arrived in the town where the killing had occurred, Vieira de Mello grilled Manning’s colleagues in the Kiwi battalion. “He was obsessed,” says Chergui. “He wanted every detail of what Manning had done all day long.” He would use the information to argue with New York that the peacekeepers’ rules of engagement should be made more aggressive. But he would also use it to soften the blow suffered by Manning’s parents, who would be left with a precise picture of the good their son had been doing the day he died. He would make a point of visiting them when he passed through New Zealand on official business.

Vieira de Mello had learned a vital lesson in Bosnia and Zaire. It was essential to signal to armed elements that the UN would not roll over. If the militants smelled weakness, he knew, they would exploit it. Therefore, in the wake of Manning’s death, he revised the peacekeepers’ rules of engagement to maximize peacekeepers’ flexibility to defend themselves and to protect civilians. Previously, peacekeepers had had to wait to be fired upon before they struck back, and they had to fire warning shots before directly targeting anybody. But henceforth the blue helmets would be able to initiate fire at suspected militia without waiting. UN soldiers and police would also be permitted to apprehend suspicious individuals on the basis of minimal evidence. Vieira de Mello authorized large police and military sweeps to drive out the militia and restore public confidence. He later reflected, “We chose not to opt for the usual and classical peacekeeping approach: taking abuse, taking bullets, taking casualties and not responding with enough force, not shooting to kill. The UN had done that before and we weren’t going to repeat it here.”

3 At a speech in which he congratulated the troops on neutralizing the threat, he presented a bellicose face of the UN. “Let them try again, and they will get the same response,” he said.

4His favorite part of the job, he made clear, involved managing military affairs. His staff teased him for his seeming delight at attending military parades in the scorching sun. A big believer in such parades ever since he had accompanied Brian Urquhart around southern Lebanon in 1982, he visited with each unit separately and often found occasions to present medals to the soldiers to boost their morale. “A parade may never have been the most important event in Sergio’s day,” recalls Jonathan Prentice, “but he knew it was likely to be the most important event in a soldier’s day.”

Neither he nor the peacekeepers had jurisdiction over West Timor, which was part of Indonesia. Nonetheless, UN humanitarian agencies like UNHCR operated there in order to help repatriate some 90,000 East Timorese refugees who had not yet returned home. On September 5, 2000, militia leader Olivio Moruk, one of nineteen men named by the Indonesian attorney general as a key orchestrator of the 1999 massacres and a suspect in the murder of Leonard Manning, was killed in his home village in West Timor. Word of his death spread quickly. The following day a funeral procession of some three thousand people wound its way past the UNHCR compound in the town of Atambua, in Indonesian-controlled West Timor. UNHCR security staff considered evacuating the office, but the local police chief assured them that the demonstration would pass peacefully. Instead, an advance group of thirty to fifty militiamen on motorbikes, armed with a mix of stones, bottles, homemade guns, and semiautomatic weapons, broke off from the march and stormed the UN office. “White people have caused our loss in the referendum,” one gunman shouted, “and now they’re causing our suffering.”

5 The men burned the UNHCR flag and raised the Indonesian flag. As the militia shouted insults nearby, Carlos Caceres, a Puerto Rican UNHCR worker inside the agency compound, responded to an e-mail from a colleague. Caceres wrote:

My next post needs to be in a tropical island without jungle fever and mad warriors. At this very moment, we are barricaded in the office. A militia leader was murdered last night. He was decapitated and had his heart and penis cut out . . . Traffic disappeared and the streets are strangely and ominously quiet. I am glad that a couple of weeks ago we bought rolls and rolls of barbed wire . . .

We sent most of the staff home, rushing to safety. I just heard someone on the radio saying that they are praying for us in the office. The militias are on the way, and I am sure they will do their best to demolish this office. The man killed was the head of one of the most notorious and criminal militia groups of East Timor. These guys act without thinking and can kill a human as easily (and painlessly) as I kill mosquitoes in my room.

You should see this office. Plywood on the windows, staff peering out through openings in the curtains hastily installed a few minutes ago. We are waiting for this enemy, we sit here like bait, unarmed, waiting for a wave to hit. I am glad to be leaving this island for three weeks. I just hope I will be able to leave tomorrow.

Carlos

Minutes after hitting “send,” Caceres was brutally hacked to death, along with Samson Aregahegan, an Ethiopian supply officer, and Pero Simundza, a Croatian telecommunications officer.

6 Their bodies were then set aflame in front of the office. Another UNHCR staffer suffered machete wounds to the head. The mob, which then ransacked and torched the UNHCR office, went around town on trucks and motorcycles inspecting private houses and hotels, saying they were looking to “finish” the “white people from UNHCR.”

7 With Vieira de Mello’s strong support, Secretary-General Annan declared “security Phase V” for West Timor, ordering the withdrawal of all international staff and the suspension of UNHCR operations until security could be established and the guilty brought to justice.

The Indonesian authorities proved uninterested in reining in the militia or rounding up the killers.

8 Conditions in West Timor remained too volatile for the UN to return. While Vieira de Mello knew that a UNHCR presence in West Timor might speed refugee repatriation, he never recommended that the UN resume its operations there because he was never satisfied that it could do so safely. The humanitarian imperative no longer trumped all other concerns.

In East Timor itself he focused on improving the performance of UN police. Although he was a committed multilateralist, he took what for him was the heretical step of deciding that on occasion geographic distribution should be sacrificed in the interest of unit cohesion. “What is more important?” he asked. “That twenty countries each send six policemen, or that the UN police stop crime?” In March 2001 UNTAET began to experiment with new models for UN policing, assigning responsibility for the Bacau district to police from a single country, the Philippines.

9 When UN officials in New York objected because they thought that the new single-nationality units were an affront to the UN ethos, Vieira de Mello successfully defended the move.

In 2001 he persuaded his friend and foil Dennis McNamara to become his deputy. He had talked up the mission and the fun they would have conspiring together once again. But by the time McNamara arrived, Vieira de Mello was drained by the relentless job pressure. His sense of play seemed to have vanished, and even though the two men had clashed often over principle in the past, they had never feuded as they did in East Timor. “Sergio didn’t want a number two,” McNamara recalls. “He wanted special assistants who were loyal to him above all.”

Vieira de Mello made McNamara responsible for cleaning up the UN Serious Crimes Unit, which was meant to pursue those responsible for crimes against humanity. Talk of an international tribunal modeled on those for Rwanda and the former Yugoslavia had quickly faded, as Western states rushed to normalize ties with Indonesia. The serious crimes panel, which consisted of two international judges and one Timorese, would investigate 1,339 murders and indict 391 suspects. Although 55 trials would be eventually held, 303 leading suspects, including the ex-governor of Timor and General Wiranto, the head of the army during the massacres, would live comfortably on the Indonesian mainland and in West Timor.

10

Vieira de Mello didn’t give McNamara support when he needed it. His deputy traveled to Indonesia to press Jakarta to arrest suspected war criminals, but Vieira de Mello backed his chief of staff, Nagalingam Parameswaran, a Malaysian who encouraged the militia leaders to return to East Timor and assured them that they would not be prosecuted. Vieira de Mello believed that if he could persuade the spoilers to reintegrate in East Timor, it would enhance East Timor’s prospects for peace. “Sergio, you’ve become like a bloody politician,” McNamara said. “How can you just let the killers go free?” Stability mattered more to Vieira de Mello than immediate justice. Although he personally supported war crimes tribunals, Gusmão and Ramos-Horta were eager to normalize ties with Indonesia, even if that required pardoning those with blood on their hands. In the role he was in, Vieira de Mello believed he should defer to their assessment that the peace of the present should be valued above reckoning for the crimes of the past. McNamara continued to press the prosecutor’s office to pursue indictments and arrests. And the clash with Parameswaran grew bitter, with the Malaysian publicly calling McNamara a “racist” and a UN oversight body accusing him of political interference in serious crimes. To McNamara’s shock his friend did not speak up for him. Instead Vieira de Mello focused on the overall mission, urging his critics in East Timor and beyond to take a long-term view and not despair. “Regularly,” he said, “we hear of aging war criminals from the Second World War being indicted.”

11FILLING THE POWER-SHARING GAP: TIMORIZATION

The UN Security Council had given Vieira de Mello a mandate to govern East Timor on his own for more than two years. During his first six months he did not challenge this assumption, even as he struggled to manage the colossal responsibilities associated with absolute powers. But in the spring of 2000, with Timorese unrest boiling over, he sent a half-dozen trusted members of his staff on a two-day retreat and asked them to return with proposals for overhauling the mission. He delivered a new set of options to the Timorese at the annual gathering of their resistance movement. “The most acute phase of the emergency is overcome,” he told the Timorese leaders. “We hear clearly your concerns that UNTAET fails to communicate or involve the East Timorese sufficiently.” He described the two alternative models. “Under the first model UNTAET and myself will continue to be the punching bag,” he told the audience, smiling. Under a second “political model” the UN would speed up the “Timorization” process and form a “co-government” in order to “share the punches with you.”

12 He would create a mixed cabinet divided evenly between four Timorese and four internationals. “Faced as we were with our own difficulties in the establishment of this mission, we did not, we could not, involve the Timorese at large as much as they were entitled to,” Vieira de Mello said. “To the extent that this was due to our omissions or neglect, I assume responsibility and express my regret. It has taken time to understand one another.”

13Gusmão recalls the sense of relief within his party. “This was the time we started to believe that Sergio was committed to the Timorese,” he says. “The Security Council had given him all of the power, but he said, ‘No, I need you.’” He approached Vieira de Mello after his speech and said, “I see this is not Cambodia after all.”

Vieira de Mello’s ties with Timorese officials improved. Ramos-Horta, the unofficial foreign minister, began to tease him for his authoritarian tendencies, referring to him as the “Saddam Hussein of East Timor” or chiding, “Sergio, you have more powers than Suharto ever did. How can you live with yourself?” Vieira de Mello could give as good as he got. He referred to Ramos-Horta as “Gromyko,” the eternal Soviet foreign minister. “José, you’ve been foreign minister of East Timor for twenty-four years. You’ve never managed a career change or a promotion.”

Officials in UN Headquarters had a different reaction: Vieira de Mello was breaking the rules. The Security Council had empowered the UN, and not the Timorese, to run the place before independence. Vieira de Mello scheduled a video conference with New York to defend his power-sharing plan. Without informing Headquarters, he invited the Timorese who were slated to become cabinet members to participate in the discussion. “Sergio knew that he was trying to do something revolutionary in the UN system,” recalls Prentice. “And his attitude was, ‘If you want to deny the Timorese power, then have the guts to fucking say it to them yourself.’” UN officials in New York muted their concerns, and on July 15, 2000, Vieira de Mello swore in a new mixed cabinet. UN officials would keep control of the police and emergency services, and the political affairs, justice, and finance portfolios. Timorese would take charge of the ministries for internal administration, infrastructure, economic affairs, and social affairs. A few months later Ramos-Horta, who had informally represented East Timor abroad for years, would become the official minister for foreign affairs. For the first time in the UN mission, high-paid foreigners would work under Timorese managers.

Some UN staff in East Timor were even more uneasy with the new arrangement than those in New York. They had not come all the way to East Timor to answer to Timorese, they said. Their contracts said that they worked for the UN secretary-general.

14 Vieira de Mello decided to confront the UN staff members who resisted the changes. He assembled the entire UN staff—some seven hundred people—along with the four new Timorese cabinet ministers, in the auditorium of the parliament building. He spoke from the dais and, pointing to the Timorese sitting in the front row, said, “These are your new bosses.” When one UN official objected that there was no provision in the UN Security Council resolution for what UNTAET was doing, he was defiant. “I assume full responsibility,” he said. “You either obey, or you can leave.”

Vieira de Mello also set out to mend fences with FALINTIL soldiers, who were still holed up in their barracks. The UN supplied $35,000 worth of humanitarian assistance per month until February 2001, when the new army, the Timorese Defense Force, was officially christened. He had stopped viewing FALINTIL through the prism of the KLA and had come to see how central the fighters were—culturally, as well as practically—to Timorese identity and stability.

Timorese leaders were only temporarily appeased by Vieira de Mello’s power-sharing initiative. They quickly grew dissatisfied with the pace of the transfer of power.

15 Sure, they were part of a mixed cabinet, but they could not fire UN staff, and the UN senior staff continued to hold their regular executive meetings without them, presenting them with regulations as if they were faits accomplis.

Although he never attacked Vieira de Mello personally, Gusmão slammed UNTAET. The Timorese were supposedly being taught “democracy,” he said, but “many of those who teach us never practiced it in their own countries.” The UN were preaching reliance on nongovernmental organizations, but “numerous NGOs live off the aid ‘business’ to poor countries.”

16

Part of what was irking Gusmão was the absence of a “transition timetable.”

17 As he remembers it:

The people were asking, How long? How long? How long? It was important psychologically to get a timeframe. If you just say “transition,” without giving specifics, ordinary Timorese will say, “Twenty-four years—yes, that was a transition!” They were asking, we were all asking, quite simply, When will the malaes [foreigners] go?

Vieira de Mello responded to Gusmão’s demands, and in January 2001 he finally laid out a political road map. An eighty-eight-member constituent assembly would be elected in August. This assembly, in turn, would draft and adopt a constitution within ninety days, decide upon the date for presidential elections, and choose the date on which East Timor would become independent. The assembly, duly elected, would decide to sign the constitution in March 2002, hold presidential elections in April, and receive full independence at long last in May.

By mid-September Vieira de Mello had formed a new cabinet, composed only of Timorese. With the deadlines in place, the Timorese were finally confident that they would soon take over, and tensions abated.

A GAP TOO FAR

Vieira de Mello had managed to bend UN rules in order to do what he thought was best for East Timor when it came to security and self-government. But he was never able to redress the greatest source of frustration in East Timor: the UN rules that forbade him from spending money directly on the country. In the economic sphere, these rules ensured that the large UN peacekeeping and political mission managed to distort local economies without being able to contribute to development. Rebuilding the country and revitalizing the economy were tasks left to the UN Development Program, the World Bank, and the International Monetary Fund. Since these agencies and funds worked slowly, the UN mission took the blame for leaving little tangible behind. The economic side of what Gusmão had called the “Cambodia trauma” was in fact being repeated in Timor.

Vieira de Mello fought with New York over taxation policy. In March 2001 he wrote to Headquarters, describing his “Solomon’s dilemma.” On the one hand, under UN rules UN staff and UN contractors could not be taxed locally. On the other hand, as the head of a government, he needed tax revenue and was sending a bad signal to the Timorese by exempting the richest people on the island from taxes. He argued the case from the Timorese perspective. If the UN paid workers extra to make up the difference in taxes, the added toll on the UN budget would be minor, while the infusion of such revenue into the Timorese budget would make a significant difference.

18 But he was again informed that the rules could not be altered.

Although he knew that the rules were the rules, he urged the Secretariat to try to see if the countries in the UN could be persuaded to change them. “What we spend on spare parts for our vehicles, for example, is the same amount as East Timor is able to spend on justice,” he wrote to Headquarters. “We spend on helicopter charters three times what is foreseen in the national budget for education.” He proposed that at a minimum after independence UN member states agree to allow UNTAET to hand over used UN assets to the East Timorese government.

19 Lacking even basic infrastructure and equipment, the Timorese welcomed hand-me-down UN vehicles, generators, computers, and other hardware. After a long struggle Vieira de Mello succeeded in getting permission to donate 11 percent of UN assets—about $8 million worth of equipment—to the new government of East Timor.

20 By claiming that East Timor’s ravaged roads were damaging UN vehicles, he also managed to get a portion of his budget used for road repair—a major victory.

The press had little knowledge of his internal struggles and started to make him a target of their attacks.

Tempo, an Indonesian weekly, published an exposé on the discrepancies between international staff (who earned an average of $7,800 per month) and local staff (who earned only $240). The article inaccurately described Vieira de Mello as the “flamboyant father of three” and as “one of the most diligent partygoers” in Dili. Living off a salary of $15,000 per month, he was said to host “lavish parties teeming with wine and food.” Although most of the facts (apart from his salary) were false, the article stung him, as its core observations—for example, the UN spent more on dental care for its peacekeepers ($7 million) than it did on local staff salaries ($5.5 million)—hit home .

21

Since he was the effective governor of the place, any criticisms of the UN mission were in effect criticisms of his leadership. In early 2001 the Brazilian daily

O Globo quoted extensively from a letter sent by an anonymous female Brazilian Catholic missionary, referred to only as “A.M.” A.M. had described UNTAET as a “job bank for foreigners” who acted like “‘pharaohs,’ arrogant and authoritarian.” UN officials drove air-conditioned SUVs, while the Timorese crowded onto trucks filled with “roosters, pigs, goat kids, bags of rice, vomit, and suffocating heat.” The majority of UN officials treated the Timorese as “monkeys,” A.M. wrote. “They do not come to serve. They come to command and to be served.”

22

Vieira de Mello stewed over the article for a month, then erupted in writing, denouncing the author. He wrote:

I am, proudly, a career functionary of the UN, ever since I left university 31 years ago. I served—or, according to your informer, I spent delightful holidays—in tourist paradises such as Bangladesh, Sudan, Cyprus, Mozambique, Peru, Lebanon, Cambodia, Bosnia, Rwanda, Kosovo and, since November 1999, East Timor . . . I left my position in New York and I came to Dili because I believed in the cause of this suffering people. I accept—in fact, I stimulate—constructive criticism, but I do not allow gratuitous attacks such as yours . . .

It was the UN that kept ablaze the flame of the right to self-determination since Indonesia’s invasion of Timor in December 1975. It was our Secretary-General who mediated the agreement of May 5, 1999, that made possible the referendum of August 30, 1999, in which more than 78 percent of the population chose independence. I lead, with humility, this mission, and I take responsibility for all of its errors. We had to improvise and, with scarce resources, to create a government in an environment of desolation . . .

We share the frustration of the people with the slow execution of these projects. If destroying is easy—it took a few days here—constructing a new public administration and civil service takes time. I did not learn to make miracles, and one of the reasons for the delay is the control mechanisms, whose objective is precisely to prevent that which your source affirms to be the norm: corruption . . .

The headline of your article was “White Intervention in East Timor.” Intervention, yes! White? There are more Asian, African and Arab people than Europeans in this mission . . . I haven’t served the UN for more than three decades to swallow gratuitous effrontery from anybody. To the readers of

O Globo I excuse myself for the tone of this reply. It is easy to assail when one does not have knowledge of the facts.

23

The one fight Vieira de Mello refused to lose with Headquarters was that over securing compensation for families of sixteen UN employees killed during the 1999 referendum. When New York requested their marriage, birth, and death certificates, as well as written proof of employment, he patiently explained by cable that East Timor presented a “very unique case” where all documentation had been destroyed and the UN would have to be flexible and accept witness statements vouching for a staff member’s employment and death. “I am sure you will agree that we have a moral obligation to staff members who died in their line of duty,” he wrote, “particularly since rampaging militias specifically targeted local staff.”

24

In March 2001 Jean-Marie Guéhenno, head of the Department of Peace-keeping Operations, wrote to Vieira de Mello expressing regret that “our hands are tied.” Despite the unusual circumstances surrounding the deaths and the compensation claims, Guéhenno wrote, the department was unable to get the standard requirements waived. More than two decades after he had battled New York for compensation for a Lebanese doctor killed by peacekeepers, Vieira de Mello argued that the UN needed to overhaul its entire approach. “In my long association with UN peacekeeping operations, the issue of the UN’s incredibly late payment of compensation to nationals of our host countries [has] always been a source of embarrassment to the Organization,” he wrote. “Victims’ families are usually very poor, and it is difficult for them to understand how the UN, which is perceived to be wealthy, could not pay compensation within a reasonable amount of time.” He informed Guéhenno that he intended to go ahead and “grant a one time lump sum payment of $10,000” to each family. Knowing how to force a response, he advised: “If I do not hear from you by 19 July, I shall direct the Director of Administration to disburse these funds immediately.”

25 This cable got New York’s attention, and Vieira de Mello’s multiyear campaign finally bore fruit. Guéhenno informed him that he had finally persuaded UN administrators to allow the Timorese families to be compensated beginning on August 1, 2001.

26Vieira de Mello’s fiercest clash with Headquarters came over his handling of petroleum, East Timor’s one potentially lucrative source of revenue. In 1989, when Australia had recognized Indonesia’s occupation of East Timor, a grateful Indonesia granted Australia generous access to oil resources that lay close to East Timor’s shores. Vieira de Mello knew that UNTAET would be considered a failure if it did not manage to persuade the Australians to return what rightfully belonged to the Timorese. Australia’s GDP dwarfed any oil revenues the country would receive from the vicinity of East Timor. By contrast, if the UN could secure the oil fields for Timor, they could potentially triple the island’s GNP.

The negotiations were tense from the start. Australian diplomats tried to claim that the oil was worth so little that the status quo should be preserved. Sensing that Australia would not give up its claim without a fight, Vieira de Mello decided to preserve his own warm ties with the Australian government by removing himself from the proceedings and appointing as the lead UN negotiator Peter Galbraith, who had been U.S. ambassador to Croatia in the Balkans and whom he had made UNTAET’s minister of political affairs. Galbraith, who could be undiplomatic, threatened to sue Australia at the International Court of Justice if it did not offer the Timorese, in accordance with the law of the sea, all revenues north of the midway point between East Timor and Australia. The Australians complained repeatedly to Vieira de Mello that Galbraith was raising Timorese expectations unreasonably and sabotaging ties between the UN and Australia. They had expected the UN to negotiate the agreement, not to act strictly in the interests of the Timorese. But the Security Council had tasked UNTAET to act as the Timorese government, so mere mediation was not appropriate. Vieira de Mello urged Galbraith to drive the best bargain for the Timorese.

In order to drive that bargain, he, Galbraith, and others in UNTAET pleaded with Headquarters to send a lawyer with expertise in petroleum law. But just as UN Headquarters took two years to respond to pleas for experts in organized crime for Kosovo, it could not quickly call upon specialists for Timor. Yet not long before a deal was to be signed divvying up one portion of the oil proceeds, UN Under-Secretary-General for Political Affairs Kieran Prendergast sent Vieira de Mello a long cable, telling him that he had consulted with an expert on the law of the sea who had said that he was giving too much away. “It will be for East Timor, as an independent nation, to define its national interest,” Prendergast wrote. Vieira de Mello was livid. “Sergio decided rightly that the way to be a success was to become more Timorese than the Timorese,” recalls Prentice. “So anything that suggested that he hadn’t placed their best interests at heart was always going to draw a rather strident response.” Vieira de Mello whipped off one of the most blistering cables of his long career, writing:

Although I read Prendergast’s memo on 1 April, I note that it was dated 22 March and was thus, despite appearances, not an April Fool’s joke . . . Headquarters was kept fully informed at each and every stage. I would have welcomed any timely advice . . . Why did I not hear previously, either in person, by telephone, or in writing? . . .

I am (I had hoped that this was presumed) fully aware that East Timor will have to live with any decision made much longer and more profoundly than will we . . . in short, contrary to the impression given, the East Timorese leadership do have minds of their own and do not simply wait, mutely, for us to provide poor advice. More frequent contact with the realities of the field—as I learnt in my career—provide a vital antidote to such misconceptions.

He defended Galbraith’s approach to the negotiations and fired back that New York was being unduly influenced by an adviser to the subsidiary of an American company called Oceanic, which had a vested interest in the negotiations. “I have yet to read of an alternative, feasible route that could have been taken that would have led to a more beneficial outcome,” he wrote. “These gains should not be jeopardized by an eleventh-hour lack of unity on the part of East Timor and the United Nations, particularly if this were to become public, which, as we all know, is regrettably a risk within the United Nations.” In a second draft of the cable, Vieira de Mello noted that while the Timorese had been made aware of his response, “The pique is mine.” And for the final draft he altered the sentence to: “The disappointment, irritation, and pique are mine.”

27

In the end Galbraith secured a deal by which the Timorese and Australians would create a Joint Petroleum Development Area, from which the Timorese would receive 90 percent of the revenues and the Australians 10 percent, a dramatic improvement over the unfair 50-50 split that predated the UN negotiations. The Bayu-Undan development within this area was thought to contain gas and oil reserves worth $6 billion to $7 billion, which would henceforth bring $5 billion in revenue to tiny East Timor.

28 The Galbraith-led negotiations would quadruple the oil available to East Timor for sale.

On April 24, 2002, East Timor’s presidential elections were held. Xanana Gusmão’s opponent said that, even though he expected to lose in a landslide, he thought it important to show the Timorese that they would have alternatives in elections. The two candidates walked together arm in arm into the polling station where they cast their votes. In a marked contrast to the August 1999 referendum, only one slight irregularity was reported in the 282 polling stations throughout the country.

29 Gusmão was elected president of East Timor with 83 percent of the vote. Vieira de Mello told Carlos Valenzuela, the Colombian who ran the elections for the UN, “Thank you for the most boring elections of my life.” East Timor was less than one month away from being a fully independent nation.

GETTING A LIFE

Part of the reason Vieira de Mello had time to work nineteen-hour days was that he had no serious romantic attachments tying him down. The job’s challenges distracted him from his loneliness. Indeed in February 2000, just two months into the new millennium, he complained memorably to his close friend in Geneva, Fabienne Morisset: “February already and still a bonkless century.”

In his isolation Vieira de Mello had settled into a routine in East Timor. He ate a sandwich in the office for lunch, used the Internet and reading packages from friends to keep up with events in the rest of the world, brought work home, dined ascetically on rice and chocolate bars, made his phone calls to New York late at night, and avoided the cocktail circuit. Kosovo had given Vieira de Mello his first taste of being a local celebrity. But as the ruler of East Timor, he was almost as well known as Gusmão. He rarely went out because his unfailing politeness toward the Timorese and toward his UN employees demanded energy and because he cherished the few hours he had to himself. When he served as the best man in the Dili wedding of his special assistant, Fabrizio Hochschild, he ducked out of the after-party early. “I’m so sorry, Fabrizio,” he told his close friend. “I just can’t take being ‘on’ anymore. I’m exhausted.” He told his friend Morisset of the hollowness he felt despite having finally reached great heights at the UN. “Everything is all swimming along professionally,” he said. “But what am I doing with my life? What is all of this for?”

In late 2000 he had met Carolina Larriera, a twenty-seven-year-old willowy, elegant Argentinian who had gone to university in New York and in 1997 had volunteered her way to a Headquarters staff job as a public information officer. In East Timor, her first field posting, she helped dispense World Bank microcredit grants to Timorese businesses. Larriera was drawn to Vieira de Mello’s familiar South American charisma, but she had heard about his exploits with women and steered clear. In October 2000, nearly a year into her posting, she briefed him on the microcredit program in advance of a donors’ conference he was attending. The pair discussed the problem of finding and retaining qualified Timorese managers. A month later, when she attended a small dinner party at Ramos-Horta’s home, Vieira de Mello approached her, and the two drifted into easy conversation. Playing up the traditional rivalry between Brazil and Argentina, he described how his mother had fled Buenos Aires and returned to Rio when she was seven months’ pregnant so as to make sure he was born in Brazil.

The pair became romantically involved in January 2001 and conducted their relationship privately. Larriera was concerned that her colleagues would judge her for her involvement with the head of the UN mission. He was not fully invested: He saw other women and concentrated mainly on work, spending many evenings at his home alone, listening to Beethoven or another somber composer and poring over paperwork, while drinking a glass of Black Label. “You can work and be involved in a meaningful relationship. The two are not incompatible,” Larriera insisted. “No, I can’t,” he said.

In September 2001, frustrated by his refusal to prioritize the relationship, she broke it off and stopped taking his phone calls. “This isn’t worth it,” she told him.“You’re not with me, and I want more.” He asked her to reconsider, but she was firm. Unless he made a real commitment, she said, they were through.

On September 11, 2001, Vieira de Mello was in Jakarta, Indonesia, meeting with senior Indonesian officials. At the end of the day he said good night to his aides and headed upstairs to his room, where he ordered room service. His cell phone rang, and it was Larriera telling him to turn on the television. The regular CNN broadcast had been interrupted and was showing the flaming World Trade Center towers that he used to view from his apartment in New York. Ibrahim, his bodyguard, knocked loudly on the door. “Mr. Sergio,” he shouted, “have you seen what happened?” When Ibrahim entered, his boss was holding his shortwave radio tuned to a French broadcast, as the English CNN broadcast played behind him. He just shook his head, speechless. “There was nothing to say,” recalls Ibrahim. “What do you say?”

On October 14, 2001, a month after the terrorist attacks, Vieira de Mello called Larriera and invited her over, saying he needed to talk. When she arrived at his Dili home, the lights were out. She let herself in through the side door and found a row of candles leading her from the doorway to the living room. Sprinkled on the floor were paper hearts that he had cut out of colored construction paper. “From now on, it’s the new Sergio!” he said, emerging. Larriera was skeptical. “I have changed,” he said. “And I will change. Don’t believe me. Watch me.” From that point on, the couple referred to their relationship before his October turnaround as their “prehistory.” “History,” he said, “begins today.”

Vieira de Mello’s closest colleagues at that time were in serious relationships. Jonathan Prentice, his special assistant, had married his high school sweetheart, Antonia, and the pair were inseparable. Hochschild, his previous assistant, had been a determined bachelor, but he and his wife had given birth to a child soon after their wedding in East Timor. Martin Griffiths, his former deputy in New York, had gotten divorced and remarried in 1999, naming Vieira de Mello the godfather of his newborn daughter. Now Vieira de Mello seemed to want what they had. He wrote to Larriera a week after they got back together, sounding like a teenager. After sending her

“un besito matinal,” or morning kiss, he wrote that he found himself thinking that what they had together was too good to be true, but he exclaimed, “Fortunately, it

is true.”

30

He filed for divorce in December 2001. Although he had lived a separate life from Annie since 1996, she took the news badly. However distant they had grown, she had never expected him to leave the marriage. But he was determined to go ahead. He wrote to Antonio Carlos Machado, his best friend in Brazil, that after “various gaffes of mine designed to duck reality,” he had decided that he was deeply in love. Noting that he had no idea how draining love could be, he wrote that it had nonetheless filled him “with a new and vital élan,” and he was determined “to make the most of what remains of my life instead of wasting the few years that are left.”

Vieira de Mello told Machado that he had what would be an exhausting six months remaining in East Timor. Afterward he planned to take three months off “so as to do many of the things I’ve dreamed of and delayed my whole life.”

31 He crammed a few of those ambitions into his weekends with Larriera in Timor. He insisted the couple climb Ramelau, Timor’s highest peak. He said he wanted to learn to scuba dive, and they got PADI certified. He announced he wanted to do the deepest dive in the area, so they plunged 130 feet off the coast of Atauro island.

At Christmastime he did something with Larriera he had done with none of his other girlfriends: He invited her home to Brazil to meet his mother. She in turn brought him to Buenos Aires, where she guided him to 1853 Vincente López Street, the house where the Vieira de Mello family had lived from the time he was twenty days old until he was three.

As his relationship with Larriera intensified, he settled into a reclusive domestic routine. She moved into his home, and they got a dog, Manchinha (Portuguese for Spot). In the early evening after the temperature cooled, they went for long runs along the coast or hiked up a nearby hill to the eighty-eight-foot-tall statue of Christ, which was modeled after the Christ the Redeemer statue above Rio de Janeiro. On the weekends they shopped at the market or continued their scuba-diving adventures with bodyguard Alain Chergui and the Prentices. As the mission began to coast along toward Timorese independence, he and Larriera even took long weekends on the nearby resort island of Bali. He grew giddy as the handover date approached, blasting the Paul McCartney song “Freedom” in their home.

In the week before East Timor’s gala independence ceremony, the Timorese leaders held a dinner in honor of their departing governor. Vieira de Mello toasted them and their future as an independent country. But he toasted most dramatically Larriera. “East Timor is special to me for many reasons,” he said, “but none more than because this is where I met Carolina. For two years we worked together in the same building in New York and never met. We had to travel to this small island ten thousand miles away in order to find one another.”

Vieira de Mello’s close friends were stunned by his transformation and by his espousal of monogamy. Many speculated that his fidelity could not last. Others disagreed, suggesting that at the pinnacle of the UN system he had realized he could not carry on relationships outside his marriage. All seemed to agree that Larriera had brought out a relaxed side to him that they had not seen in such abundance before. Morisset recalls long talks with him while he was in East Timor:

Sergio couldn’t accept getting old, getting less handsome. He’d always been preoccupied with his looks, but in later years he became obsessive about his fitness. He wanted to stay a seductive young guy. This was his role. This was his identity. This was what made him famous. And Carolina awakened in him his youth.

As he focused on his future with Larriera, he hoped that Secretary-General Annan would compensate him for having stranded him in Timor for two and a half years. He told Larriera, “He has the obligation to send me to a civilized place, to a decent post.”

But as his mission approached its end, Annan did not tell him where he was heading next. When a journalist asked Vieira de Mello his plans, he answered testily: “Regarding my next mission, you will have to address that question to the Secretary-General. I do not know yet.”

32 As he boxed up the life he had built in Timor, he exclaimed to McNamara, “Where am I supposed to send my fucking boxes?” He could not understand how senior officials in New York were not more empathetic toward those who slogged away in the field. “Some of those bastards in New York should try this sometime,” he said.

Vieira de Mello reflected publicly on where the mission had succeeded and failed. “When I arrived in 1999, I felt like an ambulance driver arriving at the site of a car crash and finding a dismembered body in a state of clinical death,” he told reporters in Dili. The UN administration had helped put the territory back on its feet, he said, but with the average Timorese still living on fifty-five cents per day, the transition would be a long one. “You don’t change the devastation of 1999 into a Garden of Eden in two and a half years,” he said, adding that “we have laid solid bases for the country to live in peace.”

33

The UN had spent $2.2 billion. It had renovated 700 schools, restored 17 rural power stations, trained thousands of teachers, recruited more than 11,000 civil servants for 15,000 posts, established two army battalions, and suited up more than 1,500 police. And Vieira de Mello had learned a valuable lesson about legitimacy: It was performance-based. “The UN cannot presume that it will be seen as legitimate by the local population in question just because in some distant Security Council chamber a piece of paper was produced,” he said. “We need to show why we are beneficial to the people on the ground, and we need to show that quickly.”

34

His biggest surprise, he said, was the Timorese “capacity to forgive.” “I have never seen it elsewhere,” he told a journalist, “and I’ve seen conflicts.” He cited regrets over handing the judiciary to the Timorese too soon and over being hemmed in by rules “too elaborate and too complex for a country that was still coming out of intensive care.”

35 “Local people have little time for rules,” he wrote later. “They want results.”

36 His final verdict? “I felt that we had done as much as an unprepared organization could have done.” When he tried to publish a self-critical report on the lessons the UN had learned, his superiors in New York forbade him from doing so.

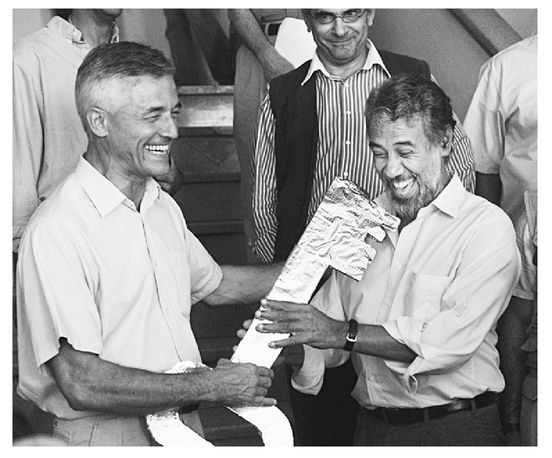

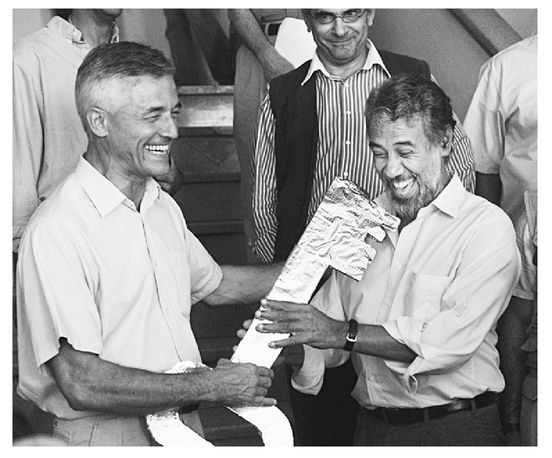

Vieira de Mello presenting Gusmão with a symbolic key to the Governor’s House, May 16, 2002.

On May 18, with President Clinton and other heads of state arriving the next day for a flag-raising ceremony, he welcomed to East Timor the parents of Leonard Manning, the New Zealand peacekeeper who had been the first UN soldier murdered by the militia. He had invited the Manning family to be his only personal guests at the independence ceremony, and Larriera accompanied them throughout their stay. He spent the eve of independence in his office, where he stayed up all night at his desk signing letters to the unheralded individuals who had helped him in East Timor. At the end of each letter he handwrote two or three sentences of personal thanks. He wrote to the UN staff, to peacekeepers (past and present), to diplomats, to the Timorese, and to Indonesians.

The next day, when Secretary-General Annan arrived, Vieira de Mello approached Annan’s assistant Nader Mousavizadeh and pleaded, “You’ve got to find me time to speak with him one-on-one. I have to find out where I’m going next. I don’t want to be left hung out to dry.” Later he and Annan sat on the terrace of his home, facing the beach, but Annan offered little clarity. The secretary-general had still not decided where to put him.

Vieira de Mello had written to U2 in the hopes that they would travel to Dili and belt out their song “Beautiful Day” on independence day, but the band’s representatives had not responded, and he ended up reaching out to his old friend Barbara Hendricks instead. At midnight on May 19, in a candlelight ceremony, the light blue UN flag was lowered in Dili as Hendricks sang “Oh, Freedom,” a Civil War-era slave spiritual. Once the UN flag had come down, the red, yellow, black, and white Timorese flag, long the flag of the Timorese resistance, was raised. Vieira de Mello had made it a point to walk a half-step behind Annan and Gusmão throughout the event, and in the moving ceremony it was Annan who officially handed over sovereignty from the United Nations to the Timorese. The longest posting of Vieira de Mello’s career had come to an end. The time he had spent at the edge of the earth, cut off from museums and concerts and friends, sweltering in the equatorial sun, ushering in the first new nation of the twenty-first century, had tested his endurance and his perennial cheeriness.

The following day, as the independence celebrations continued and the Timorese leaders mingled with Clinton and a dozen other heads of state, Vieira de Mello slipped away and went for a run with Larriera—his first without bodyguards in East Timor.

At noon on May 21 Taur Matan Ruak, the former guerrilla leader and head of the Timorese army, arrived at the airport with his colleague Paulo Martins, the head of police. They expected a crowded Timorese send-off for Vieira de Mello. But as Matan Ruak recalls, “We arrived and nobody was there. Then Sergio and Carolina arrived, and then the time started moving, and still nobody came.” Matan Ruak was furious at his governmental colleagues for not paying more respect. “Not to say good-bye to Sergio, after all he did for East Timor . . . was to betray him,” Matan Ruak says. “The only consolation was that we knew we’d have many more chances to thank him properly.”

Matan Ruak embraced Vieira de Mello before he boarded the plane. “Thank you,” he said. “You will have friends here forever.” Vieira de Mello ascended the steps onto a small jet with Jonathan and Antonia Prentice, and with Larriera.

He had been saying for months that he could hardly wait to toast the end of his mission, and Prentice had brought two bottles of champagne onto the plane. But as Vieira de Mello rested his head against the window, he was flooded with melancholy. He pressed his hand up to the glass, as if to say good-bye. And as the faces of the few Timorese on the tarmac faded into the distance, he turned away from the window, buried his head in Larriera’s lap, and sobbed.