Nineteen

“YOU CAN’T HELP PEOPLE FROM A DISTANCE”

Vieira de Mello, bodyguard Gamal Ibrahim (right), and UN spokesman Ahmad Fawzi (left) at the Baghdad airport, June 2, 2003.

“A TEAM”

Vieira de Mello knew little about Iraq but a lot about helping societies that were emerging from tyranny and conflict. He understood that, on such a short mission, it was even more essential than usual to assemble the best possible team. Before leaving New York, he asked Rick Hooper, the American Arabic-speaking political analyst, and Salman Ahmed, an American who had been Lakhdar Brahimi’s aide in Afghanistan, to work with his own special assistant Jonathan Prentice to assemble an “A team.” “I want Arabic speakers,” he said, “and I want my team members to be with me when I get off the plane.” He needed to establish momentum right away.

Among the Arabic speakers he tapped were Nadia Younes, an Egyptian who had been Bernard Kouchner’s chief of staff in Kosovo; Jamal Benomar, a Moroccan lawyer who before joining the UN had been jailed for eight years in his country as a human rights activist; Ahmad Fawzi, an Egyptian who had been Brahimi’s spokesman during Afghanistan’s Bonn Conference; Mona Rishmawi, a Palestinian human rights officer; and Jean-Sélim Kanaan, a French-Egyptian veteran of Kosovo who had a reputation as a master logistician and acute political operator. Among the others he brought, in addition to Prentice and Ahmed, were Fiona Watson, a Scottish political officer who had been working on Iraq issues from New York; Carole Ray, his British secretary in Geneva; and Alain Chergui and Gamal Ibrahim, who had been his bodyguards in East Timor. Because Vieira de Mello offered his friend Dennis McNamara a seat on his plane, McNamara found himself named UNHCR special envoy to Iraq.

Vieira de Mello was not one to take no for an answer. He had made an art form out of teasing, flattering, and pressuring to get what he wanted. When Lyn Manuel, who had been his secretary in New York and East Timor, initially declined his offer, on the grounds that her daughter was getting married, he kept pushing. When she finally accepted, her supervisor in New York refused, but Vieira de Mello got Iqbal Riza, Annan’s chief of staff, to overrule him. He believed that UN staff should by definition be readily available to undertake any field mission at any time, in much the same way he was. And he used the same argument with junior and senior staff that he knew Annan would have made to him, had he refused the job: The mission was important for Iraq and for the UN, and their services were indispensable. Vieira de Mello had accepted the job on May 22, 2003, the day Resolution 1483 had been passed. He stopped off in Cyprus for briefings on June 1, and would fly with his team to Baghdad the following day.

He knew that his most important choice would be his political adviser. On the advice of Riza, he met in Cyprus with Ghassan Salamé, a former Lebanese minister of culture and professor of international relations at the prestigious Institut d’études politiques (Sciences Po) in Paris. Salamé had studied the politics and history of Iraq and had long been acquainted with leading Iraqi opposition officials and intellectuals, as well as members of the Ba’ath regime. His book, Democracy without Democrats, and his occasional columns in the pan-Arab daily newspaper al-Hayat had been banned in Iraq, but his name was known.

At their meeting in Cyprus, Vieira de Mello said: “I don’t know much about Iraq. I need to pick your brain on who’s who, and how the country is moving.” Salamé warned that the influence of Iraq’s neighbors was going to increase and not diminish in the coming months, and he said that by deciding to demobilize an army of more than 400,000 soldiers, the Americans had committed “hari kari.”

1 After two hours of discussion it was clear that they clicked. Salamé had opposed the war, but he wanted to do what he could to help the UN end the Coalition’s occupation.

On the flight from Cyprus to Baghdad on June 2, Vieira de Mello wore a finely tailored gray suit, a crisp starched white shirt, and an emerald green Ferragamo tie (“the color of Islam,” he said), given to him on his birthday by Larriera, who was getting her paperwork sorted and would join him on June 15. He had grown very sentimental. In his briefcase he carried the paper hearts that he had cut up in East Timor and sprinkled on the floor on the night they got back together in 2001.

He characteristically used the plane ride to study his only real instructions from the major powers: Resolution 1483. He focused on its provision “stressing the right of the Iraqi people freely to determine their own political future.” The resolution did not stipulate what the UN would do to make that happen. After exercising absolute power in East Timor, he was unaccustomed to the helping verbs that defined his functions. In Iraq it would not be up to him to devise laws or political structures; he would “encourage” and “promote” measures to improve Iraqi welfare. This meant that he would make inroads only insofar as the Coalition accepted his advice. “I think I could just as easily ‘encourage’ progress from Geneva,” he joked.

The UN mandate was awkward to say the least. Instead of negotiating with the local government, as UN officials usually did in countries where they deployed, his team would have to negotiate with the invaders, who had dismantled local structures. He knew that a large part of what he was there to do was to stress publicly and repeatedly that the day of Iraqi self-rule was near.

Before the group left Cyprus, Prentice had printed up a dozen copies of the draft statement he would deliver on the tarmac upon landing. On the plane each UN official offered his or her suggested changes, and Vieira de Mello incorporated half a dozen of them. The statement seemed relatively pro forma, and some on the plane were puzzled by his perfectionism. “For a three-minute speech, it seemed excessive to scrutinize and rescrutinize every clause,” remembers Fawzi, the spokesman. “But for Sergio it had to be just so.” Well practiced at descending into foreign lands, he had long understood what American planners had not adequately grasped before invading Iraq: Outsiders almost never get a second chance to make a first impression.

When the flight touched down in Baghdad, he disembarked from the plane. He had expected a large turnout, as the “return of the UN” was being widely hailed in the region and beyond. But when he stepped into the Baghdad heat, about a dozen journalists were on the tarmac to greet him. UN officials later learned that Paul Bremer had held his own press conference a short time before their arrival. After all of the intensity of the previous weeks, when the UN officials got off the plane and saw so few journalists, one recalls, “It felt like a bust.” As he disembarked, Vieira de Mello called Larriera in New York and insisted she turn on the television to watch his first press conference.

He spoke as meticulously as he dressed. He tucked his prepared text into his breast pocket and gave the appearance of speaking off the cuff: “The day when Iraqis govern themselves must come quickly,” he declared. “In the coming days, I intend to listen intensively to what the Iraqi people have to say.”

2But when it came to reaching out to “the Iraqi people,” he was unsure where to start. He asked Prentice to pester Salamé, who was back in Paris, and to call him every day, sometimes several times a day. Vieira de Mello too would call. “Where are you?” he would ask. “Why aren’t you here?” Salamé explained that he could not simply zip off to Baghdad for a month. He was not a career UN civil servant who was accustomed to routinely disappearing on a moment’s notice. Vieira de Mello was unforgiving: “I need you. Iraq needs you.” Salamé succumbed to his new boss’s charm, but then the UN administrators failed him. “People keep calling me from all over the UN system,” he complained to Vieira de Mello. “Each of them has told me that they know I am going to Baghdad and need my details. But for all of the phone calls, I still don’t have an airplane ticket!” “Welcome to the UN,” said Vieira de Mello.

Salamé ended up arriving in Baghdad on June 9, exactly one week after the rest of the A team. It did not take long for the two men, who would become inseparable, to begin bantering. “Ghassan, straighten your tie,” Vieira de Mello would rib his unkempt adviser before their high-level meetings. Salamé smoked two cigars each day, and his new boss urged him to stop. “You don’t want to die young like my father,” he said. One month into the mission Salamé, whom Vieira de Mello had nicknamed “the wazir,” or minister, made motions to depart. “Of course you’re not thinking of leaving,” Vieira de Mello said. “The universities in Paris don’t start until October, so we will leave together, wazir.”

One vital source of experience in the country was the UN humanitarian coordinator in Iraq, Ramiro Lopes da Silva. Lopes da Silva had lived in Baghdad from 2002 until just before the Coalition invasion, and he had led the first UN mission back to Iraq on May 1. He had been a member of Vieira de Mello’s ten-day assessment mission in Kosovo in 1999, and as native Portuguese-speakers, they shared a cultural bond. There was so much work to be done that the labor could be divided naturally between humanitarian and reconstruction tasks, which Lopes da Silva managed, and political tasks, which Vieira de Mello oversaw. Lopes da Silva would continue coordinating the work of the humanitarian agencies and would develop a plan for liquidating the Oil for Food Program.

3 Vieira de Mello, who preferred high politics to “grocery delivery,” would work with the Coalition to try to speed the end of the occupation. He had somehow to earn the trust of the Iraqis and develop a strong working relationship with the Coalition. He knew that suspicious Iraqis, who were angry about a spike in violent crime and the seeming permanence of American rule, would not necessarily see these tasks as complementary.

PLAYING IN THEIR GARDEN

When Vieira de Mello arrived in East Timor in 1999, the Timorese had been hugely grateful to the UN for having staged the referendum on independence. But when he landed in Iraq, he knew that Saddam Hussein had demonized the UN weapons inspectors and the Oil for Food Program. The inspectors were cast as meddling agents of Washington. And the Oil for Food officials, although technically offering humanitarian succor to needy citizens, were symbols of the UN sanctions that had crippled the Iraqi economy. He was aware that he was inheriting the sins of his predecessors. For all of the disadvantages of having a past in Iraq, however, there were also advantages. While the Coalition continued to rely disproportionately on Iraqi exiles for intelligence, the UN had three thousand Iraqi staff members who had remained enmeshed in the country even during the invasion. He thought he would have an easier time than Bremer in getting a read on the Iraqi street. Unlike in East Timor, he did not have to scrounge up offices, computers, vehicles, or translators. He and his team moved into offices in the Canal Hotel, a white, three-story former hotel training college that had been converted into UN headquarters in the 1980s. Trimmed with the UN’s trademark light blue paint, and located in the eastern suburbs of Baghdad, the site was well known to Iraqis.

He set out to make the Canal familiar to the Americans as well. On June 3, his first full day in Baghdad, he ventured to the four-and-a-half-square-mile fortified district along the Tigris that had already become known as the Green Zone. When the U.S. Army’s Third Infantry Division fought its way into downtown Baghdad, it had chosen Saddam Hussein’s seat of power as the Coalition’s own and converted the modern Ba’ath party headquarters, the National Assembly, and the 258-room Republican Palace into the Coalition’s offices.

4 Concrete blast walls and rolls of concertina razor wire were erected around the eight-mile perimeter, and sandbagged U.S. machine-gun posts warded off intruders.

As U.S. soldiers inspected the badges of officials in the UN convoy, Vieira de Mello observed the long, wending line of Iraqis queuing up outside the American barricades to apply for work and to register complaints. Before they were allowed to enter, they were patted down, some roughly. He shook his head. “There go the hearts and minds,” he muttered to Prentice.

There was much that was off-putting about the Green Zone. During the evening Americans danced in the disco of the Rashid Hotel, where Hussein’s son Uday had once held vicious court, and gift shops would soon sell T-shirts depicting Uncle Sam daring insurgents to BRING IT ON!

5 Several thousand internationals (mainly Americans but including some British, Australians, Dutch, Japanese, Poles, and Spanish who were part of the Coalition) shuttled among former Iraqi government buildings adorned with murals of Babylonian glory. They strolled along boulevards lined with eucalyptus and palm trees, wearing safari vests, combat boots, and cargo pants. And they slept in prefabricated housing containers. Their phones carried New York (914) area codes, meaning that when the Iraqi phone system was restored, reaching an Iraqi would carry the price of an overseas call.

6 The manicured lawns and sparse traffic inside the Green Zone presented a study in contrasts with the congested chaos of the unpoliced urban gridlock outside the walls. Even Coalition staff had begun to refer to their island of residence and work as “The Bubble.”

7 In a phone conversation with Bernard Kouchner, his successor in administering Kosovo, Vieira de Mello would marvel at the Americans’ insulation in the Green Zone. “You know the way they are,” he told Kouchner. “It is just like Camp Bondsteel in Kosovo. They have created their own wooden town. They stay in their barracks. They leave in armored cars. They wear flak jackets. They barely go out and when they do they return as quickly as possible.”

When Vieira de Mello and his UN team entered the palace where Bremer had set up shop, they saw clean-scrubbed Americans emerging from offices marked for various ministries. This was the first time he really comprehended that the Coalition considered itself the actual government of Iraq. Not wanting to alienate Bremer from the start, he mainly listened, holding back his own views. He had expected to hear the details of Bremer’s plan for devolving power, but he quickly realized that Coalition officials had no such plan. They were improvising.

Bremer’s top American adviser was Ryan Crocker, the Arabist whom Vieira de Mello had befriended in Beirut in 1982. “Sergio is as good as it gets not only in the UN, but in international diplomacy,” Crocker had told Bremer before their first meeting. “He is the personification of what the UN could be and should be but rarely is.” Bremer would make up his own mind. “He didn’t take my word for it,” Crocker recalls. “He had to see for himself.”

Bremer explained that he saw phase one of the transition as the uprooting of the old regime and the establishment of law and order and basic services. “We expect to turn the corner in the next month or so,” he said, seemingly unaware that the wholesale evisceration of the old regime that he had undertaken was at odds with the establishment of law and order. They would then proceed to phase two, which included economic reconstruction, job creation, and the formation of democratic bodies. On the all-important political side, Bremer said, he intended to appoint a group of Iraqis to a constitutional conference, where they would draft a new constitution that would be submitted to Iraqis for a referendum. Vieira de Mello winced at the idea that the constitution would be drafted before general elections were held, as it would thus seem like an illegitimate American charter. Bremer said that he would also appoint a “consultative committee” composed of representatives from all religious, political, and social backgrounds. This committee in turn would appoint Iraqi technocrats to the different ministries to work with the American and British ministers in charge.

8 Bremer was impressed with what he saw of Vieira de Mello. “The Iraqis were concerned, and we were concerned, about whether the UN would play a helpful role or not,” the American remembers. “The thing that pleased me is that Sergio said he wouldn’t work against us and he wouldn’t stand off. He wanted to work with us.”

This didn’t sit well with some of Vieira de Mello’s own staff. After the meeting in the Green Zone, he returned to the Canal Hotel to discuss the UN’s options with his staff. Benomar, one of his political advisers, insisted that the Coalition was in violation of Resolution 1483 because it had taken over the governing functions of Iraq. He urged Vieira de Mello to press for the immediate creation of an Iraqi government. Marwan Ali, a Palestinian UN political aide who had attended university in Iraq, complained about the vagueness of the Security Council resolution, which offered no guidance on how the UN should interact with either the Americans or the Iraqis. “It’s constructive vagueness,” Vieira de Mello attempted. “There’s no such thing as constructive vagueness in Iraq,” Ali countered. “It’s just vague vagueness.” Most members of the team recognized that the CPA had established facts on the ground that the UN would not be able to alter. The majority felt that the only way the UN could make a meaningful difference in Iraq would be not to denounce the Coalition but to persuade it to alter its approach. Vieira de Mello sided with the pragmatists. “We can’t just sit at the Canal Hotel and do nothing,” he said. “You can’t help people from a distance.”

In his meetings with American and British officials, he never focused on whether the Coalition should have been in Iraq in the first place. “Sergio didn’t bother himself with whether the war was right or wrong,” says Prentice. “The war was a fact. The occupation was a fact. You’ve got two choices when you have those facts: Either you can try to help the Iraqi people out of the mess and urge a swift end to the occupation. Or you can take the moral high ground and turn your back on it.” Throughout his career Vieira de Mello had often spoken of the importance of “black boxing” intentions. “By taking the Americans at their word, and then making them abide by those words,” he told colleagues, “you can create leverage.” This was what he had done with the Khmer Rouge in Cambodia and with the Serbs in Bosnia. It was also what the UN had done with Indonesia when Jakarta had agreed to a referendum in East Timor and then been forced to stand by the results.

On his third night in Baghdad, Vieira de Mello had dinner with John Sawers, the British diplomat who served as Bremer’s deputy. Since it was still a relatively calm time, the two men sat out on the terrace in the open air, eating steaks and drinking Iraqi beer late into the evening. Vieira de Mello’s adult experience in the Islamic world had been confined to his tours of Sudan in 1973-74 and Lebanon in 1981-83. He spoke fluent English, French, Italian, Portuguese, and Spanish and mediocre Tetum (the Timorese dialect), but he spoke hardly a word of Arabic. Sawers noted Vieira de Mello’s self-consciousness about his linguistic handicap. “Here was one of the greatest linguists in the history of the UN system,” recalls Sawers, “and he could barely say hello and good-bye in Arabic. He was not pleased.”

Vieira de Mello knew that most UN officials who had amassed Middle East experience had also acquired baggage. He consoled himself that as an outsider he might bring fresh eyes to the country’s challenges. His main asset wasn’t his Iraq-specific knowledge, but his problem-solving experience and his war-tested ability to charm thugs. Carina Perelli, the head of the UN Electoral Assistance Division, called him an “encantador de serpientes,” a mesmerizing charmer of even the most poisonous snakes. While dining with Sawers, Vieira de Mello offered a comparative perspective, speaking at length about what he took to be the lesson of East Timor. “The Timorese were okay with the UN in charge for a certain, brief period of time, but at a certain point we had to switch to a support role,” he said. “You’ll have to do the same.” In the early weeks of his time in Iraq, when Vieira de Mello had a suggestion to make, he would forward it to Sawers. “If Bremer thinks these are British ideas rather than UN ideas,” he liked to say, “they are far more likely to be accepted!” Sawers suggested that the UN co-locate with the Americans and the British in the Green Zone. But Vieira de Mello dismissed the idea, saying, “My instincts are to keep a degree of distance from the Coalition. And that will require some physical distance.”

Nadia Younes, his chief of staff, managed the UN’s day-to-day ties with the Coalition. At the first large meeting between midlevel U.S. and UN officials in the Green Zone,Younes passed around copies of UN Resolution 1483, and the group went over the text line by line.The Americans looked flummoxed. “What does ‘encourage’ mean?” a U.S. official asked. “We don’t know,” Younes replied. “You wrote the thing!” Her colleague Benomar remembers, “The CPA made it clear that it expected the UN to issue a press release from time to time applauding the Coalition’s efforts. They would do everything and we would clap.” It would take many more meetings for Coalition officials to see the UN role as anything more than either cosmetic or confrontational. For Bremer the resolution was useful because it made clear that there was only one ruler of Iraq: “We were the occupying authority. We were the sovereign. Under international law you are either sovereign or you are not. It’s like being pregnant. Under 1483 the role that Sergio and the UN could play was limited. They were there to help us.”

While Vieira de Mello soon managed to win Bremer’s respect (if never his full trust), other U.S. officials remained suspicious of the UN. In late June Vieira de Mello was stopped at a Coalition checkpoint on the airport road. Alain Chergui, who was part of his team of bodyguards, told a U.S. soldier that under international rules UN vehicles were not to be checked. The young soldier refused to let the UN convoy pass. “Do you know who is in the car?” Chergui said, frustrated. “No, and I don’t care,” the soldier replied. Chergui called Patrick Kennedy, Bremer’s chief of staff, who agreed to intervene. But Chergui got nowhere when he told the soldier who was on the line. “Is he civilian?” the soldier asked. Chergui nodded. “Then I don’t give a shit.” When Ibrahim,Vieira de Mello’s more hot-tempered bodyguard, began to pick a fight with another one of the Coalition soldiers, the special representative finally stepped out of the car and placed a call to Bremer, who reached somebody in the military chain of command, who eventually ordered the convoy through. On subsequent occasions when the UN bodyguards (several of whom were French and thus believed the Americans were deliberately hostile) ended up in quarrels, Chergui told his colleagues to muzzle their fury. “You have to stay cool, or we will impair Sergio’s job for silly reasons,” he said. “The Americans don’t want us here to begin with. We are playing in their garden.”

The mistrust was mutual. Almost all UN staff had opposed the U.S.-led invasion. They thought that the Coalition staff, who were vetted by Rumsfeld’s office at the Pentagon, were frighteningly young and inexperienced. Most were Republicans, and many dreamed aloud of turning Iraq into a free market laboratory. A growing number had adopted Bremer’s dress code, trudging around in khakis, blue blazers, and desert combat boots. While two-thirds of Vieira de Mello’s closest advisers spoke Arabic, very few in Bremer’s senior circle did.

9Jeff Davie, a colonel in the Australian Defense Forces who served as Vieira de Mello’s military adviser, experienced this mutual suspicion firsthand.When Davie first reached Baghdad, his suitcases carrying his regular Australian military uniform lagged behind, and he wore civilian clothes. UN officials embraced him, as he provided invaluable insight into the Coalition, of which Australia was a member. But ten days into his posting, his Australian khakis arrived, and he began wearing them to work, along with his blue beret. UN staff were horrified. “Suddenly they saw a Coalition soldier emerging out of the office next to Sergio’s. I looked like a fifth columnist,” he recalls. “They couldn’t believe Sergio would hire somebody like me.” The reception was no warmer over in the Green Zone. He remembers, “The Coalition said, ‘You’re wearing a blue beret; we can’t trust you,’ and the UN staff said,‘You’re wearing a Coalition uniform; we can’t trust you.’”

LAW AND ORDER GAP

Looking back, it is almost impossible to recall the brief period, between early April and late June 2003, when Iraq was a relatively peaceful place. The two months after Saddam Hussein’s statue was pulled to the ground by American soldiers brought some joyous scenes of Iraqis celebrating the toppling of the tyrant and some traumatic scenes in which families located the remains of missing relatives. But mainly those two months brought creeping uncertainty and shock that the Coalition wasn’t more organized.

The Baghdad that Vieira de Mello and his team entered was nowhere near as dangerous as Khmer Rouge territory in 1992, besieged Sarajevo in 1993, or war-torn Kosovo in May 1999. The Iraqis that Vieira de Mello met were worried about theft, unemployment, lack of electricity, and the indignity of a foreign occupation, but they were not worried about an imminent civil war or suicide bomb attacks. A nascent insurgency was afoot, but it was Coalition forces who were being targeted, and it initially seemed as though the attacks were a last gasp by the prior regime. In a few short months the attacks on “soft targets” in Baghdad would grow so frequent that the city outside the small Green Zone would become known as the Red Zone. But that was not the Iraq of June 2003.

Typically the head of a UN mission (here,Vieira de Mello) automatically assumed the role of “designated security official” and bore the ultimate responsibility for staff safety. But since Lopes da Silva already carried the title from having run the UN humanitarian mission before the war, and since Vieira de Mello would be on the road constantly and was to remain in Iraq only until September 30, Lopes da Silva retained the security reins. “I’m here for four months,” Vieira de Mello told his colleague. “Don’t try to get me involved in that!”

The biggest concern preoccupying Iraqis and internationals alike was crime, which was not unusual after the fall of a regime.

10 Vieira de Mello and Lopes da Silva were worried that UN staff would be robbed or accidentally caught near Coalition personnel who came under fire. “Our biggest fear was ‘wrong place, wrong time’ incidents,” Lopes da Silva remembers.

While Lopes da Silva offered the last word on security within the mission, Robert Adolph, an ex-U.S. Marine, was day-to-day security coordinator. One of Adolph’s first tasks was to find secure accommodation for UN staff in Baghdad, which proved difficult. Most hotels seemed infiltrated with shady characters from the past regime or woefully exposed. The first batch of UN arrivals had slept under their desks at the Canal and then moved out into a “tent city” in the field adjoining UN headquarters. On May 28 Adolph had announced that UN staff were permitted to leave the Canal premises and take up rooms in one of a dozen hotels that his team had cleared. It was assumed that UN staff would live in hotels only temporarily. Once security improved and crime subsided, the staff would likely rent their own private apartments or houses as they had in other UN missions.

Vieira de Mello was given a suite on one of the top floors of the Sheraton Hotel, where the elevators rarely worked, and he felt vulnerable. “How would I make it down all these stairs if the hotel were hit?” he asked Chergui, his bodyguard. “It is insecure and insecurable,” Chergui said. Vieira de Mello insisted that he be moved to the less trafficked Cedar Hotel, which he was in late June.

11In Saddam Hussein’s day Iraq had been virtually crime free, and the UN base at the Canal Hotel, guarded by Iraqi diplomatic police, had been safe. When Lopes da Silva returned to his old office on May 1, he had found the Iraqi guards gone and U.S. troops from the Second Armored Cavalry Regiment using the Canal as their command headquarters. He was told that back in April, in the wake of the U.S. takeover, local looters had pounced on the then-deserted Canal and begun ransacking it, stealing cars, desks, computers, air conditioners, and all else they could pilfer. U.S. soldiers had ended up taking over the hotel because a group of Iraqi UN staff had emerged from hiding and hailed them to come and stop the rampage. With the return of the UN’s humanitarian and Oil for Food Program staff in May and the arrival of Vieira de Mello’s small political team in June, the American presence had been reduced to a light shield around the perimeter of the compound. Unarmed Iraqis manned the front gates. Iraqis entered and exited all day, meeting UN staff in the cafeteria for tea and coffee. It was as easy to enter as the U.S. embassy in Beirut had been two decades before. As was the case with most halfhearted security measures, the UN guards inconvenienced without deterring or impeding.

Veteran security officers were concerned that if a bomb aimed at Coalition forces went off nearby, it might shatter some of the Canal Hotel’s many glass windows. Indeed, five days before Vieira de Mello’s arrival, Coalition forces near the Canal had exploded ordnance that broke several. When a building survey revealed that some 1,260 square meters of the Canal’s outer glass was exposed, the UN Security Management Team (SMT) resolved to cover up the windows with blast-resistant film. But because it was not clear which administrative budget should cover the expense, the matter was deferred.

12 Lopes da Silva and Adolph also found that the perimeter fencing around the complex had numerous breaches and ordered the construction of a wall to enclose the Canal. The wall would be thirteen feet high with spiking on top. But because elaborate UN rules required an open bidding process, it would take six weeks to award the construction contract.

13Iraq’s law-and-order problem grew more severe by the day. Because of his de-Ba’athification and demobilization decrees, Bremer had alienated the very Iraqi forces that might have maintained security. Because Secretary Rumsfeld had sent in too few U.S. troops to control Iraq’s borders and blanket the country, foreign insurgents passed easily in and out of Iraq from Iran and Syria. And because of the absence of support in the UN Security Council for the war, other UN member states did not chip in postwar stability forces or civilian police in the way they had done for the peacekeeping missions in Cambodia, Bosnia, Kosovo, and East Timor. The ministries that kept Iraqi garbage collected, buses running, and electricity intact were now run by American and British citizens who neither spoke Arabic nor had ever managed such tasks in the United States or the U.K. And the unemployed Iraqi ex-army officers, who had been assured by Jay Garner that they would retain their jobs, felt betrayed by the Coalition. Since the Coalition had no Iraqi security partner, it had to build a brand-new security force from scratch. And now it had a new concern: The soldiers in the old army had kept their guns.

Vieira de Mello urged Bremer to scale back the de-Ba’athification edict and to meet the needs of the Iraqi army veterans. He reminded the U.S. administrator that all over the world UN officials had amassed experience setting up programs to reintegrate demobilized soldiers. Most promisingly, in one meeting he told Bremer that the top adviser to Javier Solana, the secretary-general of the European Union, had written to the UN to make an as-yet-informal offer of Spanish civil guards, Italian carabinieri, and French gendarmerie. Instead of eagerly seizing the opportunity, which might have lightened the U.S. load, Bremer said that if the Europeans wanted to contribute police, they would have to place them at the disposal of the Coalition.

14Each time Vieira de Mello visited Bremer in the Green Zone, it had grown more fortified. Sandbags piled up around the outer entrance, and the lines of Iraqis attempting to get inside twisted farther into the distance. At the Canal Hotel, by contrast, Iraqis could just walk up to the guard booth and request entry. If somebody inside vouched for the visitor, he or she was ushered inside and steered to the appropriate UN staffer, who would hear his or her complaint or request. Iraq was a country riddled by grievances, past and present. Once it became known that the UN (unlike the CPA) would not turn Iraqi petitioners away, ousted Ba’ath party members, demobilized officers, and relatives of those detained by Coalition forces began gathering at the Canal gate in the hopes of securing redress.

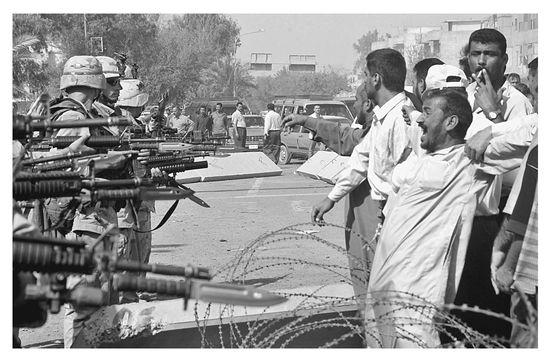

A former Iraqi soldier outside the Green Zone, June 18, 2003. A U.S. military spokesman confirmed that U.S. soldiers killed two Iraqis during the demonstration.

On June 18 some two thousand former Iraqi officers gathered outside the Green Zone to protest the disbanding of the army. While the protest raged, a small group of officers peeled off and made their way to the Canal Hotel in the hopes of convincing Vieira de Mello to help them get reinstated. He promised he would serve as an intermediary with Bremer. But Bremer rejected Vieira de Mello’s appeals, and when Salamé relayed the news to the officers, they turned and walked away from the Canal. “There go the future insurgents,” Benomar said to Salamé, who nodded. “Yes,” he said. “I see bullets in their eyes.”

LEARNING TOUR

In order to be of actual use to Bremer and to Iraq, Vieira de Mello felt he needed to learn a lot in a hurry. In his early weeks he deliberately refrained from speaking to the media. When he finally gave his first major press conference on June 24, 2003, he explained, “You may have noticed that over the past three weeks I have been rather quiet. That is because I have been listening, traveling, and learning.” Mortified that Bremer had ordered de-Ba’athification and demobilization after spending so little time in Iraq, Vieira de Mello was determined to look before he leaped. When he set out to learn, he did not learn on the fly. He developed a game plan that would enable him to glean the needs and interests of the Iraqis systematically. “Okay, who am I meeting today?” he would ask his staff in the morning. They had divided Iraqi society into categories: political parties, professional associations, nongovernmental organizations, human rights groups, lawyers, judges, women’s groups, and religious groups. Once he had made his way through the list of Baghdad contacts, he announced, “Okay, now I’m heading out to the regions.” Influential Iraqis were identified in Basra, Mosul, Erbil, Sulaimaniya, Hilla, and Najaf. “Bremer didn’t have time to talk to people,” Salamé recalls. “Because Resolution 1483 gave the UN no real tasks, we had all the time in the world to listen.”

At the time Vieira de Mello launched his learning tour, the Americans had little contact with Iraq’s religious leaders. His political officers believed that the UN could valuably contribute to stability if they could enlist the support of the powerful clerics, especially Shiite cleric Ayatollah Ali al-Sistani. Salamé sent out feelers through Dr. Aquila al-Hashimi, a powerful Shiite Muslim in Baghdad who spoke fluent French and English and seemed likely to be named Iraq’s first ambassador to the UN. When she confirmed that her uncle, an influential cleric in Najaf, was willing to help arrange a meeting with al-Sistani,Vieira de Mello knew he had scored a coup. “Ya’llah!” he exclaimed.

The politics of the June 28 trip were complex. “There are three forces in Najaf,” Salamé said, “the pope, Sistani; the black sheep, Moqtada al-Sadr; and the politician, Mohammed Baqir al-Hakim. Ideally we would make three trips to Najaf.” Even Vieira de Mello had his limits, and he couldn’t imagine driving the two and a half hours there and back on three separate occasions. “Okay, we’ll meet with all three,” he said, “but we’ll have lunch with none of them.” They dined with al-Hashimi’s uncle, Sheikh Mohammed al-Faridhi, who had organized the visit.

After meeting briefly with al-Faridhi at his home in Najaf, the delegation headed into a meeting that Vieira de Mello knew would be the most important of his time in Iraq. Al-Sistani brought a political agenda to the meeting that surprised his UN visitors. In a soft voice hardly more audible than a whisper, al-Sistani said the Americans had no business privatizing state-owned enterprises, as that was the job of a sovereign government. And he wanted the UN to act more autonomously from the Coalition. He said the organization should condemn a recent U.S. helicopter attack at the Syrian-Iraqi border. Vieira de Mello promised to look into the incident.

The most important part of the discussion concerned the future Iraqi constitution. Al-Sistani said that he was planning to issue a fatwa that said that only Iraqis could write the founding charter. This was directed at Noah Feldman, the Arabic-speaking professor of constitutional and Islamic law at New York University who was said to be drafting Iraq’s constitution for the Coalition. “Samahet al Sayyid,” Vieira de Mello said, using the Arabic expression for “your eminence,” which he had rehearsed on the drive from Baghdad, “I understand you want the constitution written by Iraqis—” Al-Sistani cut him off. “I didn’t say the constitution should be written by Iraqis,” the cleric said sharply, clutching the hand of Marwan Ali, who was translating. “I said it should be written by elected Iraqis.” Vieira de Mello nodded and said that he had learned the same lesson in East Timor.

Without realizing the significance of what he had said, Vieira de Mello had set himself up in direct opposition to the Coalition, which planned to appoint a committee of its own to draft the constitution. In one respect, his instinct to stand up to Bremer was the right one, as the Coalition was paying too little heed to just how discredited any U.S.-picked drafters of the constitution would be. But with his casual statement, the UN special representative had also implicitly raised expectations that elections could be held quickly, which was technically impossible. Al-Sistani would frequently refer to his meeting with Vieira de Mello when he insisted that only the decisions of elected Iraqis should be recognized as law. Bremer would be incensed. “It would take us months to undo the damage that Sergio did in that one meeting,” he recalls.

After meeting with Sistani, Vieira de Mello was shown the sacred shrine where Imam Ali was buried. “I want to go into the mausoleum,” he said to Salamé, who shook his head, explaining that a bloody confrontation had occurred there a few weeks before. With the same enthusiasm with which he had snapped photos of the Khmer Rouge, Vieira de Mello pleaded, “No, Ghassan, we must. I may not get back here again.” Salamé asked al-Faridhi whether they might enter the mosque’s outer mausoleum, but Vieira de Mello pressed, “I want to go inside.” Salamé recalls al-Faridhi turning white with panic and begging them to leave quietly. A large group of Iraqis was gathering around the mysterious assemblage of foreigners. Some had begun murmuring to one another, “What are the foreigners doing here?” “Out now, Sergio,” Salamé said, firmly. “Why?” he asked. “Out now,” Salamé said. “Sergio was discovering the world of Iraq,” recalls a member of his UN team. “From an intellectual point of view, he wanted to see everything, and sometimes he was oblivious to the political sensitivities.”

The UN team enjoyed a relatively relaxed lunch with al-Fahridi, then proceeded to their meeting with Moqtada al-Sadr, the twenty-something radical who was amassing a large and violent following and whom Bremer was shunning. When Vieira de Mello entered, al-Sadr sat on the ground chain-smoking, along with two of his religious aides.Vieira de Mello offered his usual introduction, describing the UN’s impartiality and expressing hope that the organization could help end the occupation that he knew al-Sadr opposed. Al-Sadr looked at him listlessly, refusing to respond. When the Iraqi finally spoke, he made plain that he knew nothing about the UN. “Can Muslim countries be members of the UN?” he asked. When Salamé said yes, he asked for examples, and Salamé told him his own country had been a founding member of the UN. Again al-Sadr lapsed into silence. After several more unsatisfying and awkward exchanges, the UN delegation got up to leave.

In their final meeting in Najaf, the UN officials met with Mohammed Baqir al-Hakim. In the 1960s al-Hakim and Mohammed Baqir al-Sadr, the f ather-in-law of Moqtada, had founded the modern Shiite Islamic political movement in Iraq. When Mohammed Baqir al-Sadr was executed in 1980, al-Hakim fled to Iran and formed the Supreme Council for the Islamic Revolution in Iraq (SCIRI). He returned to Iraq in May 2003 and was denounced by Moqtada, who did not believe that he had a claim to Shiite political leadership.

15 This meeting went far better, as al-Hakim was warm and personable. He explained Iraqi impatience with the Coalition by analogizing Iraq’s occupation to a cat that a man acquired in order to free his house of mice. “He got a cat, which got rid of the mouse,” al-Hakim said. But then, unfortunately, “the cat wouldn’t leave.”

16On their drive back to Baghdad, Salamé congratulated Vieira de Mello on an impressive day establishing the UN’s distinct credentials, and he told him that their meeting with al-Sistani could prove important. “You know you made a big statement there,” he said, referring to his endorsement of al-Sistani’s electoral ground rule. Vieira de Mello punched Salamé playfully and resorted to what was becoming his favorite quip: “You know, Ghassan, I don’t want to become a Bremello!”

Three days after the meeting al-Sistani issued his fatwa saying he would not recognize the legitimacy of any constitution that was not written by an elected Iraqi assembly. He also said that the UN had agreed with him. Bremer asked Vieira de Mello to refute the cleric’s claim as a misrepresentation of the UN position, but he refused, hoping that perhaps the Coalition would at least speed its election planning. In a note to a UN colleague soon thereafter, he sounded upbeat: “I feel confident that the UN will truly, as opposed to rhetorically, be able to play its ‘vital role’ in Iraq.”

17POWER SHARING AND LEGITIMACY

Over the years he had found that Americans tended not to appreciate the importance of legitimacy. He saw the toll the U.S. occupation was taking on Iraqi morale. “You need to be sure to accommodate Iraqi pride and Iraqi trauma,” he told Sawers.

18 Iraqi patience would last longer, he stressed, if people received tangible, material dividends from the Coalition. But the Americans and British were not offering impressive returns. Jean-Sélim Kanaan, one of Vieira de Mello’s political aides, wrote letters to his wife, Laura Dolci-Kanaan, a UN official in Geneva, in which he reflected on the Americans he was encountering in the Green Zone:

To see young fresh Americans sent from their virgin suburbs playing the sorcerer’s apprentices on questions as significant as the systems of pension, the national distribution networks of wages or the ministerial reorganization . . . is somewhat surreal . . .

We pass from the doors on which panels were quickly posted that announce triumphantly: “Minister of Health,” “Minister of Transportation.” Behind the door, one often finds seated a good American . . . He is the minister. It doesn’t matter that within five meters from there the revolt thunders and that he has practically no contact with the men and women in his ministry of supervision.

But how could he? As soon as he wants to take three steps, he must be escorted by two overflowing vehicles of soldiers armed up to their teeth and often very nervous. He crosses the city without really seeing it . . . Iraq today is an occupied country, and poorly occupied.

19

Kanaan, whose father was Egyptian and mother was French, had been able to read and write Arabic since he was a child, but he had never mastered spoken Arabic. He had been thrilled to earn a spot on the A team, but in his phone calls home he described his mounting horror at American unpreparedness. “In the UN we’ve screwed up a lot of times,” Kanaan told his wife. “But for all of our mistakes in Bosnia and Kosovo, we were never this bad. The Americans had no plan. Absolutely no plan!”

Vieira de Mello shared Kanaan’s horror at the Coalition’s blunders, but he also saw that the Americans’ lack of experience and competence created an opening for the UN. His team had genuine insight to offer on how to develop a power-sharing plan. “Iraqis need to know that they will get tangible, executive authority at the end of this first phase,” Vieira de Mello told Coalition officials.

20

The UN had a wealth of experience with elections, constitutions, and timetables for transitions. In their weekly meetings Vieira de Mello urged Bremer to begin planning for elections, which would take close to a year to organize. He appealed to him to present the Iraqi people with a transparent timeline that spelled out the process by which they would come to control their destinies. In East Timor he had come to regret his original failure to offer such a road map. He e-mailed Carina Perelli of the UN Electoral Assistance Division in New York and told her that he was pushing Bremer to launch a voter-registration drive, which would be “a tangible demonstration of intent by the CPA that its rhetoric about handing over sovereignty to a representative Iraqi government as soon as possible actually has substance.”

21

Seeing elections as a wedge into larger political influence for the UN, he asked Perelli to come to Baghdad to conduct a feasibility study. Most of the e-mail, which was copied to a variety of UN officials, was written in formal English, but knowing Perelli was in South America awaiting the birth of her niece,Vieira de Mello signed off in Spanish:

“No me vengas con el cuento de que tenías vacaciones programadas en Montevideo: yo tenía planeado pasar tres semanas en Rio . . . !” (Don’t come to me with the story of how you had time off planned in Montevideo: I had planned to spend three weeks in Rio . . . !) As was his wont, he followed up often to be sure Perelli would come quickly. “It will be a breezy 50 degrees (Celsius!) [122 Fahrenheit] or higher in Baghdad by the time you come,” he wrote, “so you will need to wrap up warm.”

22Bremer’s political plans raised a wide assortment of red flags with Vieira de Mello. He remembered the hostility that his creation of a nonexecutive, consultative body had engendered in East Timor, which was a relatively homogeneous society in comparison to Iraq. If Bremer gave the Iraqis on his new advisory council titles without responsibilities, they would be seen as American puppets. If Bremer handpicked the members of the new body, the same could be true. Decisions of whom to include and exclude would have unforeseen consequences, and foreigners were never well placed to anticipate them. On the other hand,Vieira de Mello appreciated Bremer’s predicament. Since it would take at least a year for Iraq to prepare for an election, and since the Security Council had put the Americans (and not the UN) in charge, Bremer saw it as his job to appoint some kind of Iraqi body quickly.

Vieira de Mello offered a range of suggestions. He urged Bremer to rename his “consultative committee” the Iraqi “provisional government.” Bremer refused, but he eventually came around to the idea that Iraqis should not be relegated to the role of mere “advisers.” Vieira de Mello convinced Bremer that “council” carried a more authoritative air than “committee.” But that was not enough. “We need to signal executive powers,” the UN special representative said. Salamé, the only native Arabic speaker in the room, leaped in. “We should put hukm in the name,” Salamé said. In Arabic hukuma meant “government,” which would give the impression that the body would have power of its own. “As soon as I heard it,” Crocker recalls, “I thought, ‘How come we didn’t think of it ourselves?’” It was settled: The new body would be called majlis al-hukm, which was translated into English as “Governing Council.”

Bremer sometimes changed his mind after consulting with Washington, and UN officials were not sure that the new name would stick. But at their next meeting with the CPA, Bremer began by asking, “When are we going to inaugurate the”—he pulled a slip of paper from his pocket and continued—“the majlis al-hukm?” Salamé winked at Vieira de Mello.

The functions of the Governing Council remained undefined. Vieira de Mello knew that the more independent governing responsibilities the new body exercised, the more the Iraqis would respect it. He urged Bremer to give it the power to manage foreign affairs, finance, security, and the constitutional process. He insisted that the Iraqis on the council be allowed to designate “ministers” and, crucially, that the council be given the power to approve the budget. But he knew he had to be careful about overreaching. “Resolution 1483 gave the UN almost no scope for maneuver,” recalls Salamé. “At any time the CPA could have told us, ‘You are trespassing,’ and they would have been right.”

Deciding just who belonged on the twenty-five-member council was no easy task. Vieira de Mello, who had spent the previous six weeks building his Rolodex, served as an intermediary between Bremer and Iraqi political, religious, and civic leaders. He pushed Bremer to allow the secretary-general of the Communist Party, Hamid Majeed Mousa, to be included. He urged that Bremer take special care to maximize Sunni membership. Aquila al-Hashimi, who had helped to arrange Vieira de Mello’s meetings in Najaf, made the cut, becoming one of just three women on the council. And he was pleased by Bremer’s appointment of Abdul Aziz al-Hakim of SCIRI, despite al-Hakim’s links to Iran. Only high-level Ba’athists were excluded.

Vieira de Mello felt proud of his contributions to the Governing Council. In a cable back to UN Headquarters in early July, he wrote that “Bremer was at pains to state that our thinking had been influential on his recalibrations.” He noted that the CPA demonstrated a “growing understanding” that the “aspirations and frustrations of Iraqis need to be dealt with by greater empathy and accommodation and that the UN has a useful role to play in this regard.”

23 Vieira de Mello saw it as a victory that only nine of the twenty-five Iraqi members of the body were exiles. But from the Iraqi perspective, six of the thirteen Shiite representatives and three of the five Sunnis were exiles, and neither the inclusion of five Kurdish representatives who had lived in northern Iraq under Saddam nor the addition of Turkmen or Christian representatives appeased the Sunni population .

24 Vieira de Mello hailed the fact that the Governing Council had the power to appoint interim ministers and propose policies, but Iraqis saw that Bremer was left with the authority to veto any of the new body’s decisions.

The UN staff were split again, this time on whether to embrace this new body. Vieira de Mello argued that, despite its manifest imperfections, the Governing Council was the “only game in town.”

25 “We have to take the leap of faith,” he said. At last Iraq would have a recognized body, and the UN would be able to offer its services to it rather than to the Americans. “This is only a start,” he insisted. “But it is a necessary start in the same way the first mixed cabinet in East Timor was a start.”

He attended the inauguration of the council on July 13, 2003. The members of the Governing Council acted as though they had not been appointed by the Coalition but had simply congealed into a body on their own. In a carefully staged visual the council summoned Bremer, Sawers, Crocker, and Vieira de Mello and “self-proclaimed themselves.” Vieira de Mello was the only non-Iraqi asked to speak at the ceremony. Wearing a pale blue tie to remind the audience of the organization he represented, he began and closed his remarks in Arabic:

“Usharifuni, an akouna ma’akum al-yaom. Wa urahhib bitashkeel majlis al-hokum.” Although he knew few words, he pronounced them effortlessly: “It is an honor to be with you today. And I welcome the formation of the Governing Council.” He hailed the gathering as the first major step toward the return of Iraqi sovereignty, and he pledged ongoing UN support. “We are here, in whatever form you wish, for as long as you want us,” he told the beaming council members.

26 Crocker watched him admiringly. “He was wrapping the blue flag around what we were trying to do politically. I thought it was an act of real political courage. It was also an act of unbelievable physical courage, although we didn’t see it at the time.”

Vieira de Mello knew that some on his staff would have preferred for him to avoid any association with the Coalition. He continued to have heated exchanges with Marwan Ali, his political aide. “Sergio, don’t you see, you’re not changing the Americans. You are helping the Americans.” But Vieira de Mello believed he was making progress and that Bremer could still go either way. The two men were getting along well. They were both handsome, charismatic, hyperachieving workaholics who knew how to take charge. Although Bremer had close ties to the neoconservatives, who were known for their anti-UN fervor, Vieira de Mello believed that Bremer was cut from a different cloth because he spoke French, Dutch, and Norwegian. This gift for languages testified to a curiosity and a breadth of perspective that he did not often find among Americans. “I’ve been giving Bremer advice on how to manage the hurt pride of the Iraqis,” he told Jonathan Steele of the

Guardian. “There’s been a gradual change in him. Everything I’m telling you, he buys.” Although Vieira de Mello had resisted his appointment to Iraq, he found the first two months of the mission exhilarating. He felt as though he was actually making inroads with the Coalition and with the Iraqis, and he naturally loved being at the center of what felt like the geopolitical universe. In an e-mail he asked Peter Galbraith why he intended to spend just a single day in Baghdad, noting that the Iraqi capital was where things were “happening . . . good and bad.”

27

Occasionally, though, he grew frustrated over Bremer’s mixed messages. He complained about the “5 p.m. syndrome,” where, he said, “I have my Bremer till 5 p.m. [or 9 a.m. D.C. time], and after 5 p.m. Washington has its Bremer.”

28 But because of his own experience being micromanaged by UN Headquarters, he sympathized with the “long screwdriver” that Bremer fought off from his higher-ups in the United States. “Bremer will succeed if he makes himself Iraq’s man in Washington rather than Washington’s man in Iraq,” he told the

Washington Post’s Rajiv Chandrasekaran over a drink. He had saved the UN mission in East Timor only by coming to that realization himself.

In conversations with visitors at this time, he swung between two extremes. On the one hand he acknowledged that the UN was a “minor player” on the scene and confessed embarrassment at its “total lack of authority.” He frequently reminded visitors: “The UN is not in charge here. The Coalition is.” But he also stressed, perhaps to convince himself, that the United Nations would not be “a rubber-stamping organization for whatever the military occupiers decide,” and he insisted that many Iraqis saw the UN as the guardian and promoter of Iraqi sovereignty.

29 He believed that the UN role would expand over time, and he expected it would be the United Nations that would help organize the country’s first free elections. He was convinced that no other body could meet twenty-first-century challenges. “Iraq is a test for both the United States and for the UN,” he said in an interview with a French journalist in Baghdad. “The world has become too complex for only one country, whatever its might, to determine the future or the destiny of humanity. The United States will realize that it is in its interest to exert its power through this multilateral filter that gives it credibility, acceptability and legitimacy. The era of empire is finished.”

30 While he was correct that the United States would eventually need the UN in Iraq, he was wrong in thinking that Washington was close to recognizing this.

On July 21, he flew to New York, where he briefed the Security Council the following day. Defending the Governing Council’s representativeness, he stressed, “What the Council needs at present is not expressions of doubt; it is not skepticism, it is not criticism, that is too easy. What it needs is Iraqi support [and] . . . the support of neighboring countries.”

31 Resolution 1483 had given the UN almost no formal authority, but he genuinely believed that his small political mission had made a tangible difference. “Can you believe we stretched our marginal mandate as far as we did?” he asked Salamé.

Despite his optimism, one thing worried him: the deteriorating security climate. “The United Nations presence in Iraq remains vulnerable to any who would seek to target our organization,” he said in his remarks before the Security Council. “Our security continues to rely significantly on the reputation of the United Nations, our ability to demonstrate, meaningfully, that we are in Iraq to assist its people.” Two days before his testimony an Iraqi driver with the UN-affiliated International Organization for Migration (IOM) had died in Mosul when he swerved into a bus in an effort to evade the gunfire coming from a passing car. And on the very day Vieira de Mello testified, a Sri Lankan with the International Committee of the Red Cross had been killed south of Baghdad. Vieira de Mello mentioned both attacks in his testimony and stressed that the Coalition bore responsibility for security. As he wound down his remarks, a woman in the gallery shouted out her criticism of the Governing Council. “This is not a legitimate body,” she yelled, “and you know that!” In the press briefing afterward, a reporter asked Vieira de Mello to elaborate on his security concerns. He said that the Shiite south and mainly Kurdish north were peaceful. “What you have is a triangle, Baghdad, the north and the west, that are particularly dangerous and risky for Coalition forces. And more recently I’m afraid for internationals as well.”

32 These were Vieira de Mello’s last words on the record before returning to Iraq.