Twenty-one

AUGUST 19, 2003

On Tuesday, August 19, Vieira de Mello and Larriera had breakfast at their hotel. When Mona Rishmawi, Vieira de Mello’s human rights adviser, joined them, they discussed the UN’s future in Iraq. In his first two months in Baghdad he had spoken of bringing the job of UN High Commissioner for Human Rights to Iraq. Beginning in August, though, he had grown anxious to get back to Geneva to bring field wisdom back to the high commissioner’s job. “In his mind he had already traveled,” recalls Rishmawi. When he returned to his post, he planned to expand a team of human rights monitors that had set up a foothold in Iraq but were having marginal impact. Over breakfast he gave the green light for Rishmawi and Larriera to go ahead with a human rights workshop the following Saturday, where the UN would help train Iraqis in human rights fact-finding and humanitarian and human rights law. He thought the workshop might be one more way for the UN to differentiate itself from the Coalition.

Most days it took twenty minutes to travel from their hotel to UN headquarters. But the traffic on the roads that day was far lighter than usual, and they reached the Canal Hotel in ten minutes. The unarmed Iraqi security guards checked the badges of those in the UN convoy, scanned the bottom of the vehicle with metal detectors, and waved the familiar faces inside the gate.

Gil Loescher and Arthur Helton, American refugee experts studying the humanitarian effect of the war for the e-magazine

OpenDemocracy.net, were just landing in Baghdad. Loescher, a fifty-eight-year-old Oxford University researcher, had flown to Amman, Jordan, from London. Helton, a fifty-four-year-old St. Louis-born lawyer based at the Council of Foreign Relations in New York, had met up with him there. And the pair had taken an uneventful flight from Amman to Baghdad.

Loescher and Helton had known Vieira de Mello a long time. Back in the 1980s they had criticized the UN’s Comprehensive Plan of Action, which he had helped negotiate and which had helped stop the hemorrhaging of Vietnamese boat people but had also given rise to human rights abuses. Loescher had argued that Vieira de Mello had deferred to the interests of states instead of upholding the rights of refugees. Helton had felt that the screening procedures designed to keep Vietnamese boat people out of neighboring countries had been unduly harsh. But they had not come to Iraq to rehash old disagreements. They were there to carry out a two-week field assessment.

Vieira de Mello had welcomed news of their visit. He wasn’t normally much for “assessments.” Too often, he thought, they were carried out by inexperienced individuals who took only cursory sweeps of a place and then boasted about the hardships they had endured “in the field” at ensuing dinner parties. Most studies offered generic or grandiose prescriptions without offering any concrete proposals for mobilizing political will among indifferent or unwilling implementing actors. Such recommendations generally went unread or unheeded. In this case, though, he welcomed an independent review of the Coalition’s performance. He had plenty of ideas as to how things ought to be done differently, and he knew that if the recommendations came from two Americans, they would gain more traction in Washington than anything that came from the UN.

From the moment they disembarked from the airplane, Loescher and Helton felt uneasy in Baghdad. Even though the men were not UN staff, a UN vehicle came to the airport to pick them up. Here they were fortunate, as UN rides had grown scarce in recent weeks. Mounting attacks on Coalition personnel had caused the UN to tighten its security regulations and require two-vehicle convoys. The airport road, which was known as Ambush Alley, was notoriously dangerous. The two men were relieved to reach the downtown, where, with the exception of the attack on the Jordanian embassy, civilians had not yet been deliberately attacked.

They traveled straight from the airport to the Green Zone, where they met with Paul Bremer, who gave them a full hour of his time. He presented a rosy picture. “There are a few security issues,” he said, “but we are getting everything under control.”

The two men were not scheduled to meet with Vieira de Mello until 4 p.m., so they used the gap in the schedule to drop their bags off at their hotel.Vieira de Mello’s secretary had made them a reservation in a hotel that was considered secure. When they arrived at the front desk, however, the receptionist told them she had no reservation on file. The UN driver took them to another hotel, but when they went up to their rooms, they discovered the doors had no locks. The men decided to find a different hotel after they returned from their meeting at the Canal Hotel.

Over at UN headquarters it had been a routine day. Larriera spent the morning away from the Canal, visiting the leading human rights, women’s rights, and legal organizations in Baghdad, in order to extend personal invitations to them to attend the Saturday human rights workshop. Bob Turner, the humanitarian official, chaired a communications strategy session on “UN messages to the Iraqi people” at 10:30 a.m. Khaled Mansour, a spokesman for the UN World Food Program, presented a paper on how to improve the UN’s standing. “The main goal,” he wrote, “is to present a UN distinct from the U.S.-led coalition as subtly as possible.”

1 In their dealing with Iraqis, Mansour argued, UN officials had to emphasize their desire “to ensure the earliest possible end of occupation.”

2Marwan Ali, the Palestinian political officer, also felt the rage of Iraqis mounting. He had been pressing Vieira de Mello to criticize the Coalition for a recent attack in the Sunni triangle that had killed an eight-year-old boy and his mother. His boss had approved the statement the previous day.“I’ve done all I can do to influence the Americans behind the scenes,” he had told Ali. “I have to start speaking out.” Ali was relieved. This would be the first-ever public UN condemnation of a Coalition human rights violation. Finally, he thought, the UN would begin to carve out an identity truly distinct from the Coalition. He hoped it wasn’t too late.

At 1:30 p.m. Vieira de Mello was scheduled to meet with Bremer and a U.S. congressional delegation in the Green Zone. Alain Chergui, the head of his close protection team, had gone on leave five days before, along with Jonathan Prentice, his assistant, and Ray, his secretary. Gaby Pichon, another French bodyguard, prepared the three-vehicle convoy, which lined up at the entrance to the building. But he soon got word that the flight of a group of American senators and representatives, including Harold Ford, Jr., Lindsey Graham, Kay Bailey Hutchinson, and John McCain, had been delayed.

3At 2 p.m. Vieira de Mello ran into Marwan Ali in the hall and inquired about whether the critical statement had been issued. He knew Ali was heading away on leave and asked where he was going. Ali said he was flying to Amman the next day. “Try to come back refreshed,” Vieira de Mello said, adding, “Don’t do anything to get yourself arrested by the Israelis!”

At 3 p.m. he met with a pair of senior International Monetary Fund (IMF) officials visiting from Washington, Scott Brown and Lorenzo Perez. Larriera, who was responsible for liaising with financial institutions, also attended. It was the most senior IMF delegation in Iraq in more than three decades.Vieira de Mello offered his advice on working with Bremer, warning Perez to walk a very fine line and to engage in such a way that Bremer felt ownership over the IMF initiatives (or else he would block them) but that Iraqis also saw the IMF programs as independent. When the meeting ended at 4 p.m., Larriera walked out with the visitors. As she exited, Vieira de Mello beckoned her back toward him, but she motioned that she needed to catch another meeting that would soon be ending. He gave her a playful hangdog look. As she raced down the stairs to catch the last few minutes of the NGO coordination meeting, she heard a woman from the International Committee of the Red Cross (ICRC) deliver a panicked report that somebody had spotted people taking down the numbers of all car license plates leaving the ICRC compound. Larriera believed the alarm serious enough to telephone Vieira de Mello, who was just about to start his next meeting. “En serio?” he asked in Portuguese. “Really?” He said his meeting with Loescher and Helton was about to start, but he wanted to discuss the details later.

Benon Sevan, an under-secretary-general of the UN and the longtime head of the UN’s Oil for Food Program (who in January 2007 would be indicted in a New York federal court on charges of bribery and conspiracy to commit wire fraud), happened to be visiting Baghdad to help liquidate the program. He was preparing for a 4 p.m. meeting with a visiting WHO delegation on the construction of hospitals in northern Iraq. His meeting was to take place in the office directly beneath Vieira de Mello’s.

Shortly before 4 p.m. Sevan poked his head into Lopes da Silva’s office and said he’d prefer to meet there instead. “Your secretary makes good coffee, I like looking at your goldfish,” he said, “and I want to smoke a cigar.” Lopes da Silva’s office had a balcony with sliding doors, ideal for a smoker.

When Loescher and Helton arrived at the Canal Hotel for their meeting with Vieira de Mello, they passed easily through security at the front gate and were ushered up two flights of stairs. Pichon, Vieira de Mello’s bodyguard, escorted the two guests from the hallway on the third floor through the small office outside Vieira de Mello’s, where his two secretaries were at their desks. Ranillo Buenaventura, a forty-seven-year-old Filipino, was subbing for Ray. Lyn Manuel, the fifty-four-year-old Filipina and eighteen-year UN veteran who had served with Vieira de Mello in East Timor, seated the guests around a knee-high glass table in the alcove near the window that looked out on the access road and the spinal hospital.

Vieira de Mello greeted his guests with warm handshakes. Younes joined the meeting, as did Fiona Watson, the Scottish political officer, who was a l ast-minute addition. Watson had just returned the day before from New York, where she had attended a budget-based management training program. She had been selected for Vieira de Mello’s A team because she had worked in Kosovo but also because in February she had helped the secretary-general pull together a strategic plan weighing the options for a UN postwar role in Iraq. She used to joke that the best-laid plans often led to the lousiest mandates.

Vieira de Mello sat closest to the window, next to Younes, on a black leather sofa. Loescher and Helton sat directly opposite them, with Loescher nearest the window. Watson sat on a chair at the end of the table facing the wall and window. Pichon and Manuel returned to their offices. It was 4:27 p.m.

Rick Hooper, one of Marwan Ali’s closest friends, was in Baghdad subbing for Prentice. Ali stopped into Hooper’s temporary office, which abutted Vieira de Mello’s, and reminded him that they were supposed to be interviewing an Iraqi lawyer who had been hired by the UN as a driver but who they both felt could be put to better use. “Give me fifteen minutes,” Hooper said. “I just need to finish one thing first.” Ali, who was leaving Baghdad the following day, shook his head. “I’ve got to buy gifts for my children before the curfew,” he said. Hooper, who had known Ali’s children since they were born, said, “Okay, I’ll do this afterward. Be right there.”

Just as Ali was leaving Hooper’s office and Vieira de Mello was getting reacquainted with Loescher and Helton, a Kamash flatbed truck was driving along Canal Road, a multilane thoroughfare divided by a fetid canal. Kamash trucks were Russian-made and had been purchased in bulk in 2002 by Saddam Hussein’s government for use in mining, agriculture, and irrigation. These flatbeds looked similar to the commercial trucks that were becoming ubiquitous around town now that reconstruction had finally begun picking up. This truck had a brown cab and an orange base. At 4:27 p.m. the driver made a right turn onto the narrow, unguarded access road that ran along the back of the Canal Hotel complex. Nobody paid much attention to the truck’s turn or to its load.

Most flatbed trucks in the vicinity of the Canal Hotel carried building supplies to fortify the wall around UN headquarters or to renovate offices in nearby buildings. But this truck wasn’t carrying cement or building tools. All that was visible on its bed was a metal casing that resembled the shell of an air-conditioner unit. Underneath the casing, though, was a cone-shaped bomb the size of a large man, which had been bundled up in 120mm and 130mm artillery shells, 60mm mortars, and hand grenades. All together some one thousand pounds of explosives were heading toward the Canal Hotel.

The truck didn’t have far to go. It drove at high speed a hundred yards down the access road, past the edge of a UN parking facility.

4 It sprayed gravel that hit the ground-floor windows and startled UN staffers.

5 When the driver reached the Canal Hotel, he turned the vehicle toward the unfinished brick wall that ran alongside the back of the building, two stories beneath the unsuspecting occupants of Vieira de Mello’s office.

After Pichon left his boss’s office, he crossed the hallway and reentered the small office for close protection officers. Just as he sat down, an enormous blast ejected him from his chair and carried him through the air. He landed fifteen feet from his desk, next to the elevator at the end of the corridor. Everything went black. Loescher, who sat across from Vieira de Mello, saw not darkness but light—the bright and sudden glare of “a million flashbulbs.”

Larriera was sitting in her small third-floor office at the top of the staircase. When she first arrived in Iraq in mid-June, she had occupied a desk beneath a tiny grated window. But because she had been visible to anyone who came up the stairs, dozens of people stopped to ask her for directions. Larriera had tired of feeling like the third-floor receptionist, and Vieira de Mello had helped her prop her desk against the wall, out of visual range of people in the hall. This move saved her life. She heard a deafening popping sound and in the same instant saw the steel grate that covered her window go flying the length of the office, along with shards of glass. Ripped from its hinges, the metal door over her left shoulder crashed down into the center of the office. The suction from the blast also caused the door to the adjoining office, that of Rishmawi, to fly open. Rishmawi stood up slowly and looked in Larriera’s direction. Larriera spotted a tiny cut in the center of her colleague’s forehead, from which blood began to trickle slowly.

Jeff Davie, Vieira de Mello’s military adviser, who had been lent to the UN from Australia, had spent the afternoon escorting a pair of UN aviation advisers around Baghdad airport. The meetings had run longer than he had expected, partly because the experts had stopped to pose for pictures at the airport. Davie had finally freed himself of his guests and was hurrying back to the Canal Hotel for a meeting with Younes.

Davie was several minutes from the Canal when his UN vehicle trembled from the force of a shock wave. When he looked to the side, he saw an enormous gray plume of smoke emerging from the area around the Canal. He called Colonel Rand Vollmer, the Coalition’s chief of operations, on his cell phone. “There was a large explosion at the hotel,” Davie said. “It’s bad. Call in a medevac now.” Vollmer immediately called the medical brigade evacuation number, and a dozen Black Hawk rescue helicopters marked with white crosses were deployed to the scene.

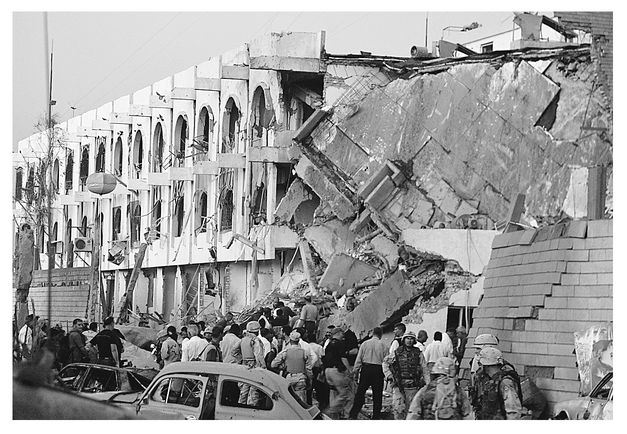

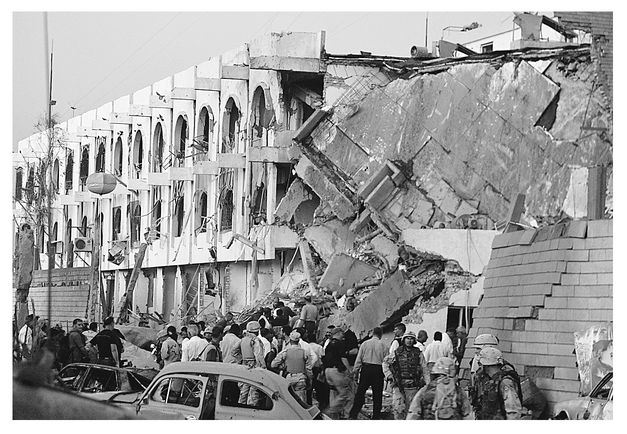

When the bomber struck, Bremer was in the Green Zone meeting with the congressional delegation that had arrived late. The palace shook with the force of the distant blast. One of his aides passed him a yellow slip of paper: “There has been an explosion at the Canal Hotel. We are attempting to raise people on the telephone there.” Ten minutes later the aide handed him a second note: “The situation looks very bad.” When the Jordanian embassy was bombed twelve days before, Bremer’s chief of staff, Patrick Kennedy, had served as the liaison between the Jordanians and the U.S. military. Now Kennedy excused himself from the meeting, called his deputy Dennis Sabal, a Marine colonel, gathered radios and a pair of cell phones, and headed to the Canal. Sabal had already seen footage of the burning UN base on CNN. He had an unusual CV in that he was the person called to manage the aftermath of the U.S. embassy bombing in Kenya, which had killed 212 people, including 12 Americans. Then, on 9/11, he had been in the Pentagon watching television coverage of the burning Twin Towers when it too was hit, and he had helped set up a morgue for the deceased. Because of these attacks, which had a common perpetrator, he had a sudden epiphany in Iraq that others would not have for many weeks: “Al-Qaeda is here,” he thought. “The minute I saw on CNN, ‘UN attacked,’” he recalls, “that was when the switch went on: Al-Qaeda had come to Iraq.”

Sergeant William von Zehle, a fifty-two-year-old retired fireman from Wilton, Connecticut, who was in Iraq as an army civil affairs officer, was sitting at his computer in the U.S. military building across the narrow lane that ran alongside the Canal. The explosion, which he thought was just outside his window, threw him to the ground. He saw an intense orange light and felt a sharp pain in his right thigh. His windows had shattered, and he had been stabbed by a four-inch piece of glass. He yanked the glass, which was like a knife blade, out of his leg and tried to scrape a piece of shrapnel from his arm. He looked at the clock on his desk, which had stopped. It was 4:28.

When von Zehle made his way to the roof of his building, he saw that the neighboring Canal Hotel was on fire. He radioed his commander and got permission to head in the direction of the attack. As he moved along the access road connecting his office building and the UN headquarters, he broke into a covered rush, cocking his AK-47 and alternating dashes with a colleague. As the pair approached the scene of the explosion, they saw that almost all of the UN’s navy blue vehicles with orange lettering that had been in the parking lot were ablaze. For the first time in Iraq, von Zehle thought his firefighting experience would be of use. “This had become a fire rescue,” he remembers. “I needed cranes, floodlights, shoring equipment.”

After a long day of patrols Captain Vance Kuhner, a U.S. reservist in charge of a military police unit, had returned to his base, a collection of tents beside Saddam Hussein’s Martyr’s Monument, a little under a mile from the Canal. After ordering his men to unload their Humvees, Kuhner was walking toward the barracks for a shower and a bite to eat. As he passed the cement volleyball court where children were playing, he was knocked to his knees by the explosion behind him. He got up quickly, turned around, and saw the dark gray cloud in the distance. “Get back in the vehicles,” he shouted to his men. “Someone’s been hit.” He assumed that a Coalition helicopter or plane had gone down, or that a U.S. convoy had been ambushed. “I need every medic I have,” he radioed his commander. Andre Valentine, a firefighter paramedic, loaded up four Humvees with six medics. “Follow the smoke,” Valentine told the driver of his Humvee.

In her small office adjoined to Vieira de Mello’s, Lyn Manuel was confused. A few seconds before the explosion she had turned her head away from her boss’s door in order to make a phone call. And almost as soon as she picked up the receiver, she had gone blind in both eyes. She thought that an electric wire had fallen from the ceiling and that she had been electrocuted. Panicked, she began crying out to her office mate, Ranillo Buenaventura. “Rannie, Rannie,” she shouted, “help me.” But when he ignored her cries, she thought perhaps he had slipped out of the office without her notice. Manuel started to call out again but quickly stopped herself. She was afraid her cries would disturb Vieira de Mello’s meeting.

Larriera had been miraculously untouched by flying debris in her office, but like Manuel, she was in a state of shock. Having seen Rishmawi stand up, she darted out of her office and began navigating her way along the pitch-black hallway toward Vieira de Mello, who she knew would be worried about her. Because of the power outage and the dust clouds, she couldn’t see down the hall, but she half-expected to bump into him as she walked. She called out his name softly: “Sergio. I’m here, Sergio . . . Are you there?” The building was still shaking from the force of the blast, and she could smell what she thought might be gunpowder.

Manuel, who still could not see, made her way out of her office in the hopes of finding help elsewhere in the building. If she had turned right instead of left, she might have fallen into a three-story pit of burning concrete, metal, and furniture. Instead she groped her way through her doorway and toward the staircase, which was in the opposite direction from the source of the explosion. In all likelihood Manuel, who was hugging one wall, passed Larriera, who was sliding along the opposite wall, but neither was aware of the other’s presence.

Larriera had a firm destination in mind. She wanted to reach the private side door to Vieira de Mello’s office—a door that only she had permission to enter. But as she continued along the wall, she saw that at the end of the corridor the lights appeared to have come back on. She was so disoriented that she wondered if she had died and was approaching the gates of heaven. Then, her reason flitting in and out, she thought that maybe the generator had kicked in and the building’s electricity had been restored. But then she realized in horror that the light she was seeing was not artificial light but Baghdad’s afternoon sunshine. The corridor ended abruptly and, where there had once been a floor and a ceiling, now only clouds and sunshine were visible above. Unable to grasp what had occurred, she turned around mechanically, retraced her steps, and attempted to enter Vieira de Mello’s office via the office of his secretaries, Manuel and Buenaventura.

The scene in their shared office was ghastly. The doors were off their hinges. Glass and debris littered the floor and desks. Papers were strewn everywhere. The air conditioners and computer screens had exploded. And a large white bookshelf had toppled onto Buenaventura’s desk. Buenaventura himself had been projected onto Manuel’s desk. He was lying in the fetal position, his eyes were fluttering, and part of his face was missing. Larriera, still uncomprehending, quickly moved into the next office, the last small room before Vieira de Mello’s. There she saw that Hooper, who was wearing a red and white checkered shirt, had pulled his swivel office chair around to the side of his desk to be closer to a person visiting him. He was leaning over in that chair, and his spine seemed unnaturally extended. The visitor, whom Larriera could not identify, turned out to be Jean-Sélim Kanaan, the French-Egyptian political officer who had returned to Baghdad the previous evening after spending a month in Geneva with his newborn son. Kanaan, who had slipped into the office just after Ali left Hooper, sat with his legs crossed in a chair. Both men were sitting in stillness and were covered in white dust. They appeared to have been crushed by beams that had fallen from the collapsed ceiling.

At the sight of these casualties, the scale of the devastation struck Larriera for the first time. She stopped calling out to Vieira de Mello softly and began screaming, “SERGIO!” But the passage in front of her was blocked by the beams and rubble piled high, and he did not answer. She turned around, exited into the corridor, and resumed her previous effort to find Vieira de Mello’s office side door. This time, when the corridor ended, she looked more carefully into the pit of rubble below. There, for the first time, she saw movement. A man covered in dust was lying on his back thirty feet below, and miraculously, he was blinking and waving his arms like a snow angel. The person below seemed too tall to be Vieira de Mello, but she thought he might be down there as well. She considered jumping into the mangled rubble, but the drop was so high that she thought she might kill both herself and the injured man. She sprinted down the corridor away from the destruction in search of Ronnie Stokes, the head of administration. Less than a minute had passed since the explosion.

The floors and beams beneath Vieira de Mello’s office had exploded upward and then crashed down. Thus his third-floor office had effectively become the first floor. The ceiling of his office and the roof of the Canal had remained largely intact, but they had collapsed diagonally. Anybody who had been on the southwest side of the building at the time of the explosion lay beneath couches, desks, computers, air conditioners, large slabs of glass from the shattered windows, and beams and concrete from the walls of the building itself.

Manuel was still blinded. As she staggered toward the stairs on the third floor, she bumped into Pichon, who had regained consciousness. He told her to get out of the building and ran past her into the office Larriera had just vacated. He came to the same devastating realization that Larriera had just reached. “There is nothing here,” he said to himself.

Ghassan Salamé, Vieira de Mello’s Lebanese political adviser, had been in his office meeting with the brother of the first former regime official the Coalition had arrested. Salamé rushed from his office to the third floor, where he joined Pichon. When he shouted out to his boss, he heard nothing back, but at the base of the rubble viewed from the corridor, he saw what Larriera had seen: a man whose entire body was covered in white dust except for his eyes, which seemed to be blinking furiously. The man waved. Salamé thought that it was Vieira de Mello. “Courage, Sergio, nous venons te sauver!” he shouted. “Let’s get to him from the back of the building,” he said to Pichon.

As Larriera rushed away from the wreckage in search of the head of administration, she saw Rishmawi, who was bleeding badly. “I can’t see,” Rishmawi cried. “I think I lost my eye.” Larriera escorted her down a flight of stairs, which were shaking and covered in dust, glass, blood, shoes, pieces of clothing, and office paper. On the second floor Rishmawi’s husband, Andrew Clapham, a legal consultant with the mission, emerged from his office, and the couple was reunited. Larriera sprinted back up the stairs. “I need to find Sergio,” she said. “Don’t, Carolina!” Rishmawi shouted. “The building is going to collapse!”

Manuel still didn’t know what was happening. She tried to feel her way down the corridor, and as she did, she felt the crunch of unnatural debris beneath her feet. She had begun hearing screams and commands ringing throughout the building, which meant that she was not the only one who had been hurt. She wiped one of her eyes and was able to make out Marwan Ali, who was running in her direction in search of his friend Rick Hooper. She called out to him. “Marwan!” He looked at her blankly, as if he didn’t recognize her. “Marwan, it’s me, Lyn,” she said. His face contorted in horror. “Lyn, my god,” he shouted. “Noooooo.” He was horrified by the sight of her. For the first time Manuel became truly frightened.

Ali picked up Manuel in his arms and carried her down the two flights of stairs to the front entrance of the Canal Hotel. He laid her down on the cement just outside and made a motion to head back inside. She cried out to him. “No, Marwan, the pavement is too hot!” she said. The cement had gathered the day’s heat and was some 160 degrees. With her one functional eye she looked down at her legs and realized she was barefoot. Her shoes had been blown off her feet. She called out again to Ali, but he had disappeared back inside the building, where many others were trapped.

Scores of UN officials spilled out of the Canal, passing Manuel on the ground. Many were bleeding profusely from cuts caused by flying glass. Two people had pieces of steel rebar protruding from them, one from his head, another through his shoulder. The aluminum office doors had been converted into stretchers.

Kuhner, the army reservist from New York in charge of the 812th Military Police, had 9/11 on his mind. He was worried about the New York police officers and firemen on his team. Two of them had already broken down. As they rushed toward the building, they had stopped suddenly. One walked back the way he had come. “I’m sorry, captain,” he had said. “I can’t.” He was having a flashback to the World Trade Center, where he had lost close friends when the buildings collapsed. The Canal too looked as if it was on the verge of imploding. Kuhner, who had no rescue experience himself, deduced the obvious: Given the size of the slabs of rubble, those trapped underneath would remain pinned there unless engineering and fire rescue equipment could be found.

Ramiro Lopes da Silva, Vieira de Mello’s deputy, was the UN official responsible for security. He had a piece of glass stuck in his forehead but was fully conscious. Benon Sevan’s desire to smoke a cigar during their 4 p.m. meeting had kept Lopes da Silva away from the side of the building where the blast occurred. He was a longtime humanitarian field worker and not a security expert, but he remembered from UN security briefings that in the event of an explosion outside, UN staff was supposed to move to a large enclosed blue-tiled courtyard. “We were always told, ‘Move in, don’t move out.’ Because out was where we thought any explosion would be. When the explosion happened inside,” he remembers, “we had no plan. We were lost. We didn’t know what to do. If we had ever thought that such an attack could occur, and if we had planned to respond to such level of emergency, the UN would not have been in Baghdad.” He joined other UN staff ducking under collapsed beams to exit the building, climbing over the fallen masonry in the corridor, and holding hands as they made their way down the staircase.

After exiting the Canal Hotel, Lopes da Silva walked around 250 feet to Tent City, where he and other UN staff had lived temporarily in early May, before the Canal reopened. The tents now acquired unexpected functions. One of the tents was converted into a first-aid facility, while another contained a satellite phone on a small table, which became what passed for a UN communications center. Lopes da Silva called Tun Myat, the head of UN security at New York Headquarters, to share information and receive guidance. “Initially,” he remembers, “nothing clicked in me about my colleagues on the third floor, about Sergio.” He assumed that the explosion had injured many but not killed anybody. Around fifteen minutes after the blast, Rishmawi approached him. “Sergio is in the building. What are you doing for Sergio?” Lopes da Silva looked confused, and she grew agitated. “Ramiro, we are in the presence of the greatest army in the world, this is what they do. Call Bremer!” Lopes da Silva left Tent City and returned to the Canal building, venturing around the back to the scene of the explosion for the first time. He saw U.S. soldiers beginning to gather at the site. He knew that the UN had neither the equipment nor the expertise for rescue and recovery efforts, and he assumed, not unreasonably, that the Coalition would have made plans to respond to large-scale attacks on civilian targets. Even though Vieira de Mello was clearly out of commission, Lopes da Silva did not consider himself in charge of the bomb scene. After just a few minutes at the back of the Canal, he returned to Tent City and resumed discussions with New York.

Back in New York, Tun Myat was not the first to learn of the attack. At 8:32 a.m. (4:32 p.m. Baghdad time) Kevin Kennedy, the former U.S. Marine and senior humanitarian official who had only left Baghdad on July 28, got out of the elevator on the thirty-sixth floor in New York and saw that he had a message on his cell phone. Bob Turner had called him just after the attack. “Car bomb, car bomb, Canal Hotel, Canal Hotel,” Turner had shouted into Kennedy’s voice mailbox. Kennedy called the UN operations room, but they had not yet heard about any bomb. Kennedy next called the thirty-eighth floor so that the secretary-general, who was on vacation with his wife on a small island off the coast of Finland, could be informed. He then sprinted the length of the corridor to find an office with a television set. CNN was showing nothing on the attack, so Kennedy hoped Turner’s message might have overstated the case. But at 9:01 a.m., thirty-three minutes after the blast, Kennedy’s face sank as CNN broadcast a “breaking news” item from Baghdad. UN headquarters in Iraq had been struck by a car bomb.

Information was spotty. Within minutes of the attack, U.S. soldiers from the Second Armored Cavalry Regiment had begun to cordon off the hotel, preventing CNN’s correspondent, Jane Arraf, from reaching the complex. But CNN did have a crew on the scene who at the time of the blast had been filming a press conference on the UN’s de-mining efforts. For the next three hours, as UN staff in Geneva and New York awaited word of their friends and colleagues, Arraf and her CNN colleague Wolf Blitzer became the relayers of bad news.

In her first commentary, at 9:01 a.m. New York time (5:01 p.m. Baghdad time), Arraf described the Canal’s shattered facade and the Black Hawk medical helicopters circling the building. She explained, inaccurately, that the UN had “beefed up security considerably, particularly in anticipation that someone might try to set off a car bomb.” But “still it was a UN building, and they really did not want to send the message that it was either an armed camp or part of the U.S. military.”

Arraf did not speculate on casualties, but within half an hour Duraid Isa Mohammed, a CNN translator and producer inside the U.S. cordon, spoke by telephone to CNN and reported that five helicopters had already evacuated casualties from the site. As he spoke, he said he was seeing stretchers carrying two victims from the building. The U.S. military, he observed, were “not answering any questions to the relatives of those local employees who came over to the scene by now and started asking questions about them. I see many women crying around here, trying to find their sons or husbands.”

6 With word of stretchers and distraught families, UN officials glued to their televisions around the world knew that this was no small attack. At around 9:30 a.m. New York time, CNN reported for the first time that Vieira de Mello had been “badly hurt.”

7

Jeff Davie had done what those who worked closest to Vieira de Mello had done: gone looking for his boss. When the traffic on Canal Road stalled, he had leaped out of the vehicle, ran to the building, and sprinted up the stairs to the third floor. He found Stokes and Buddy Tillett, a supply officer, inspecting the offices to see who had been wounded. In one third-floor office Davie found Henrik Kolstrup, a fifty-two-year-old Dane who was in charge of the UN Development Program in Iraq. Kolstrup was alive but covered in glass wounds. As he writhed in pain on the floor, he was cutting himself further on the broken glass. Davie hastily wrapped Kolstrup’s wounded upper body. Stokes and Tillett arrived with a stretcher and carried Kolstrup down the stairs to the wounded area. Davie continued on toward Vieira de Mello’s office. Kolstrup was contorting so badly that he almost fell off the stretcher and down the gap in the stairwell.

8When Davie made his way to Vieira de Mello’s office, he looked down through a collapsed part of the office wall and spotted below the same person Larriera, Pichon, and Salamé had seen lying faceup in the rubble and covered in dust. The man, who Davie did not think was his boss, appeared to be lying on a portion of Vieira de Mello’s office floor, which had now become the ground floor. Davie noted that while the damage caused by the attack was colossal, many of the floors and ceilings, including the flat roof of the building, had at least fallen in large slabs, pancake style, creating voids. A narrow tunnel, no wider than three feet in diameter at the top and at least thirty feet deep, separated Davie from the man below. Davie assumed Vieira de Mello was lying in the heap somewhere near this man, and he hurried down the stairs to try to find another point of entry.

Normally, in order to reach the rear of the Canal Hotel, Davie would have needed to exit through the front entrance and walk the entire width and depth of the building. But this time, at the base of the Canal Hotel staircase, he tried to turn right into those offices that had stood beneath Vieira de Mello’s. He was able to enter a cavity the size of a small room. But as he tried to move through the room, he was stopped by what appeared to be the roof of the first floor. He exited the cavity, which was pitch dark, and found a better path through the rubble of two partially intact offices. The walls and windows of these offices had been so thoroughly vaporized by the attack that he was able to walk through them to the outside rear of the building, where the truck had detonated. He was staggered by the destruction before him.

After leaving Rishmawi, Larriera had headed back upstairs to the third floor, but she felt helpless. She had watched UN staffers Stokes and Tillett open up a supply closet and remove what appeared to be the building’s only two stretchers. She went back down the stairs and caught up with Rishmawi again at the entrance to the Canal. “Have you seen him?!” she asked desperately. An Iraqi security guard approached them and said that he had seen the UN head of mission walking out of the building. Even though Larriera had left Vieira de Mello’s office ten minutes before the blast and spoken with him just two minutes before it, and though it would not have been like him to walk away from such mayhem, the Iraqi sounded so authoritative that she clung to the hope, imagining that perhaps he had taken charge of the rescue from outside the building. An American soldier trying to clear the scene approached Larriera with authority. “Ma’am,” he told her mechanically, “you’ve got to take care of yourself.We’ll take care of the rescue.”

Standing at the building entrance, she spotted a bulldozer moving across the parking lot, past the burned-out armored car that she and Vieira de Mello had driven to work in that morning, and toward the back of the building. She ran toward the bulldozer. As she did so, she spotted Stokes, who had carried Kolstrup downstairs and was standing at the entrance to the building. “Where is Sergio?” she cried out to him as she ran. “He is alive,” he shouted back. “He has been found.” “But where is he?” she yelled. Stokes pointed to the enormous pile of rubble at the corner of the building. “Over there,” Stokes said. “He is trapped in the rubble.”

Andre Valentine, the New York firefighter and EMT, had been one of the first U.S. medics to arrive at the scene, reaching the Canal around fifteen minutes after he heard the explosion. U.S. soldiers were already beginning to establish a security perimeter, but Valentine recalls, “We didn’t know who was involved or if the bad guys were still inside.” Accustomed to responding to emergencies in the United States, where a command post is established rapidly, Valentine was frustrated by the chaos. A few cool-headed U.S. personnel and UN officials had set up a treatment triage area in a grassy patch at the Canal entrance, but most UN staffers were milling about unhelpfully. “Don’t worry about calling the United Nations in New York City to tell them you got blown up,” Valentine said, infuriated by UN officials on their cell phones who were getting in his way. “It’s pretty obvious by now. Put the damn phone in your pocket. Stop smoking. I could use your help.” He grew so enraged that he instructed the U.S. soldiers around him to forbid anybody who wasn’t a medic from entering the three-hundred-foot perimeter treatment area. “I want you to shoot to kill anybody other than a four-star general who comes through here,” said Valentine. The other medics looked at him, unsure if he was serious.

Lyn Manuel had not moved. She lay propped up outside the building entrance, as dozens of her hysterical colleagues streamed past her. She tried to get the attention of someone with a cell phone so she could call her husband in Queens, New York. That year her brother had been killed in a hunting accident, and her father had died of a heart attack, and Manuel worried that her mother’s aging heart would not withstand the news of an attack on UN headquarters. But no matter how hard she tried, Manuel was unable to get the attention of those around her. People who looked at her quickly turned their heads away. “I am not good,” she cried out to Shawbo Taher, the Iraqi Kurd who was Salamé’s assistant. “I am not good,” she repeated. Taher tried to reassure her: “No, Lyn, you are good. Nothing is wrong with you. It’s just small injuries.” But as Taher recalls, “Her face was a piece of meat, a piece of bloody red meat.” The Americans were ordering anybody who could move of their own accord to evacuate the area. There was still a chance that the building would collapse. Manuel, who was still losing blood, began to lose consciousness. As she did, she took note of the scene around her. She was surrounded by bodies, beige and lifeless.

Lieutenant Colonel John Curran, who oversaw the medical evacuation, did a remarkable job. He had put his men through elaborate planning drills, rehearsing an evacuation from the Canal and scoping the neighborhood for locations where helicopters could land in the event of an emergency. Thanks to his foresight and the performance of his regiment support squadron, the injured (including Manuel) were rushed from the staging area to trucks and helicopters, then flown to U.S. medical facilities. Although many would die that day, nobody would die because of the tardiness of evacuation.

Ralf Embro, an EMT colleague of Valentine’s in the 812th Military Police unit, helped manage the shuttling of bodies between the treatment area and the helicopter landing area. Embro helped load the injured onto military trucks and helicopters. Over the next three hours, the trucks and helicopters shuttled some 150 wounded to more than a dozen U.S. military and Iraqi hospitals around the Baghdad area, then onward to more sophisticated facilities in Amman and Kuwait City.

Jeff Davie, Ghassam Salamé, and Gaby Pichon had each taken a different route to the rear of the building, where the bomber had struck. They had each stood up on the third floor and stared into the pit of human and material debris and concluded that, if their boss was alive, he would have to be reached from below and not from above.

Davie began prying at the rubble from the spot in the rear of the Canal that he thought approximated where Vieira de Mello would have been holding his meeting. Almost as soon as he pulled some of the lighter concrete away and created a slight gap, he heard a voice that sounded like the one he was looking for. Davie squeezed up to his waist between what appeared to be a slab of the roof and a slab of the third floor, and he shouted out to the person who had made noise. Miraculously, Vieira de Mello answered, this time clearly. “Jeff, my legs,” he said. More than half an hour had elapsed since Davie arrived at the hotel.

Vieira de Mello, whom Davie couldn’t see but could now hear, was conscious and lucid. But while he knew his legs had been injured, he could not describe his physical predicament. Pinned beneath the rubble, he could neither see nor feel his legs. After a minute or two Davie removed himself from the gap and shouted out to Pichon, who was digging through the rubble some thirty feet away. “Sergio is alive!” Davie said. “But he’s trapped between the floors.”

Davie climbed on the rubble and spotted a twenty-inch gap between two slabs of concrete. From here, he saw the same man who had waved at him when he had been up on the third floor. Davie reached through the debris to hold his hand and spoke with him through the gap. The man said he had lost at least part of one of his legs. He said his name was Gil. It was Gil Loescher, the refugee expert who had flown in from Amman that morning. Davie told Loescher that he would go and find help.

As he raced around the Canal Hotel, Davie grabbed the first U.S. soldier he could find. It was William von Zehle, the Connecticut fireman, who was helping Valentine, Embro, and the others with medical triage in the staging area. “We’ve got people trapped,” Davie said. He escorted von Zehle around the building to the mound of rubble where Loescher was buried. Davie told the soldier that the only way to reach Loescher was likely from the shaft on the third floor. He did not think the same was true of Vieira de Mello, who sounded far enough away—at least ten feet—to require his own separate rescue effort. After taking Loescher’s pulse, von Zehle quickly left the rubble pile and made his way from the rear to the front entrance of the building, where he hoped to reach Loescher.

Annie Vieira de Mello and her two sons, Laurent and Adrien, had not yet received word of the attack. They had spent a hot afternoon at the Personnaz family lake home in France, where she and Vieira de Mello had vacationed so often when their sons were young. As they returned to shore and moored the boat, Annie saw her sister-in-law’s mother rushing toward the dock. “There’s been an attack!” she screamed. “Something has happened to Sergio!” Annie rushed past her and raced in her car to Massongy. Laurent and Adrien followed in the car behind. They frantically turned the radio dial in the hopes of receiving news but could confirm only that the UN headquarters in Baghdad had been attacked. When they reached their home, they turned on the television and saw the monstrous pile of rubble under which their father was buried. The crawl at the bottom of the screen gave them hope. It said their father was injured in the explosion, but that he had been given water.

After leaving Loescher in von Zehle’s care, Davie hustled back to the gap where he had spoken to Vieira de Mello. But in the short time he had been away, the opening he had cleared had half-filled with mud. Mud was not something Davie expected to find in parched Baghdad, but he saw that Iraqi concrete was made of cement on the outside and clay on the inside. The bomb blast had shredded the concrete and caused the water pipes to burst, so the clay and the water were blending together, forcing the survivors and rescuers to worry about mud slides and suffocation as well as further structural collapses. Vieira de Mello’s voice had grown faint. “Jeff, I can’t breathe,” he said. Davie, slowed by the narrowness of the space, began removing the mud and rubble from the hole. After around ten minutes, Vieira de Mello’s voice became clearer. “I can breathe,” he said. “I can see light.”

Davie emerged again from the gap. The Americans brought small shovels, around a foot long, which were almost useless in prying away slabs of the wall and ceiling. But most soldiers were preoccupied with security, which, unlike rescue, was what they had been trained for. Colonel Mark Calvert, a squadron commander in the Second Armored Cavalry Regiment, put in place an impenetrable cordon around the building. The security he established around the site, using 450 men, was airtight. What was missing were professional rescue workers and equipment, which were what Vieira de Mello and others trapped needed. “We came to the fight with what we had,” recalls Calvert. “But were the tools adequate for the fight? No way. We just weren’t trained or equipped to rescue people after that kind of attack.”

For around an hour Pichon joined Davie in attempting to clear rubble from the gap. Davie continued to speak with Vieira de Mello, mainly to keep him conscious and to try to pinpoint his location. “I am facing a large flat object,” Vieira de Mello said. “It’s dark,” he said. “My head and one arm are free.” He asked for water, but Davie could not reach him to provide it. Vieira de Mello repeated, “Jeff, my legs,” many times. He also asked constantly about the members of his team. “Jeff, the others . . . where are they . . . who is treating them?” he asked. “Where is Carolina? . . . Where are Gaby and the others? Please look for them. Please don’t leave them . . .don’t pull out.”

9William von Zehle had been an EMT since 1975. He knew from past rescue missions that the best way, and often the only way, to extract trapped people from collapsed buildings was from the inside. After briefly speaking with Loescher at the rear of the building, he had gone inside and arrived at the edge of the collapse on the third floor. Overlooking the pit of rubble, he felt as though he were standing on a balcony of a motel. He had a radio, but it didn’t get reception, so he used his cell phone to telephone Scott Hill, his commander. “Tell my wife and kids I love them because I might not be coming back,” he said. Hill was taken aback. “Roger that,” he said. Von Zehle took off his flak jacket and prepared to enter the shaft.

He used the rebar rods poking out of the shattered concrete as hand grips to lower himself down. The rubble was so unstable that as he leaned against the debris, it frequently gave way beneath or beside him. He knew that one of the gravest risks to those trapped below was that, in his attempt to reach them, he would unleash a mini-avalanche, killing them all.

After von Zehle had ventured down around fifteen feet, the hole widened slightly. When he reached Loescher at the base of the shaft, he saw another man to Loescher’s right and his own left. This man had his back to the center of the shaft. He was lying on his right side. His right arm seemed to be pointing downward, as if he had been attempting to break his fall. His legs were buried in debris, and he seemed to be boxed in between two slabs of concrete. One slab faced him, while another slab lay several inches above him. Are you okay?” von Zehle shouted. “I’m alive,” the man said. “I’m Bill,” von Zehle said. “What’s your name?” “I’m Sergio,” he said.

Although Vieira de Mello had not been visible from the top of the shaft on the third floor, he was so close to Loescher that the two men could nearly have touched hands.Vieira de Mello had been carrying on scattered conversations with his rescuers on the outside, but it had taken a tremendous strain to be heard. Now able to speak more easily to von Zehle, he asked if anybody had been killed.Von Zehle said yes but did not know who or how many. “I’m not going to get out of here, am I?” Vieira de Mello asked.“Don’t worry,” the rescuer assured him. “You have my word:We’ll get you guys both out.”

Von Zehle knew the predicament of both men was dire, but he had managed more severe rescues in the past. He telephoned his superior officer on his cell phone again. “I need rope, lighting, morphine, reinforcing rods and f our-by-fours to hold the debris up, and screw jacks,” he said. In his four months in Baghdad he had tried to help get the fire department up and running. He knew firsthand that the department did not have the supplies he needed. “I hope the army engineering folks have them,” he said to himself.

The attack had occurred in the sector of Baghdad under the control of the Second Armored Cavalry Regiment (ACR). But the ACR consisted mainly of war fighters and had only one company of light engineers. As a result, after the attack it turned to the First Armored Division’s engineering battalions, based out at Baghdad International Airport, which operated heavy engineering equipment. These combat engineers were in Iraq to build base camps, bunkers, roads, airfields, and bridges. But the equipment they used for construction could also be used for rescue and recovery operations. The 1457th Engineering Battalion, based out of Utah, which had wheeled rather than tracked engineering equipment and which prided itself in serving as the army’s 9-1-1 unit, had been designated as emergency first responder in Iraq.

True to form, when the attack on the UN occurred, Major John Hansen, the operations officer with the 1457th Engineering Battalion, dispatched two separate contingents to the scene. One group, with the 671st Bridge Company, had spent the day bolting and extending a portable Maybe Johnson bridge across a river that was a ten-minute drive from the Canal Hotel. Hansen directed half of the men at the bridge, around fifteen soldiers, to UN headquarters to assist with the rescue. He told them to bring with them the heavy equipment they had been using to push the bridge across the river. The bridge company arrived around an hour after the explosion, but they were directed toward securing and clearing the outer perimeter of the Canal complex, not toward assisting the ongoing rescue efforts. They used a backhoe (a tractor with a large bucket on the front) to clear out the UN’s SUVs, which were burning and smoldering and which had been scattered widely by the blast.

Hansen had also instructed a platoon of combat engineers at their airport base to saddle up and make their way to the scene of the explosion. This took time, as the platoon did not have designated equipment sets ready to go. The gear they packed included suits and gas masks to ward off nuclear, biological, or chemical fumes; pioneer kits, which contained axes, pickaxes, saws, ropes, round-mouthed shovels, square-mouthed shovels, crowbars, rigging devices, and hand tools; a half-dozen dump trucks; a tracked vehicle with one big arm known as a hydraulic excavator, so big it had to be moved on a flatbed truck; and several small emplacement excavators, which were lightweight all-wheel-drive high-mobility vehicles with digging arms, chain saws, jackhammers, and a hydraulic rock drill attached to a hose. The 1457th combat engineers did not arrive with this equipment at the Canal Hotel until approximately three hours after the blast, and even then they were not directed either to the rear of the building or inside, where their mobile equipment might have been of use.

Von Zehle needed more than equipment. He also needed help. At six feet two and 180 pounds, he was too big to maneuver in the space between Loescher and Vieira de Mello. He had been able to put an IV in Loescher’s right arm. But Vieira de Mello was not nearly as exposed, and all he could do was to try to pull the rubble away by hand and prop up a few heavier slabs of concrete to stabilize the debris around him.

Von Zehle asked Vieira de Mello whether he could move his toes. He said he could. “How about your fingers?” He could. “What day of the week is it?” “Tuesday,” he answered. Von Zehle was satisfied that he was lucid and could be rescued. “Is Carolina okay?” he asked. “Is she your wife?” von Zehle asked. Vieira de Mello grunted yes. Von Zehle was surprised and thought, “I don’t think his wife is here with him in Baghdad.” But Vieira de Mello did not seem delirious. “I didn’t know who this man was,” recalls von Zehle, “but it was obvious he was somebody who was a take-charge kind of guy.” He had many questions. “How bad is the explosion?” he asked. “How many people are hurt?” Because Vieira de Mello never mentioned who he was, von Zehle learned only later that he had been treating the UN head of mission.

Around thirty minutes after von Zehle had descended into the hole, three faces appeared in the light at the top of the shaft. “Can we help you?” one asked. Von Zehle wasn’t achieving much with his solo digging, but he worried that well-intentioned soldiers lacking search-and-rescue experience would only make matters worse. “Any of you have any training in this?” he asked. Two of the men shook their heads, but one said the words he had been waiting to hear. “I’m a firefighter paramedic from New York City,” the man said. Von Zehle eyed the five-foot-seven, 150-pound man above. It was Andre Valentine, the medic who had been running triage at the entrance to the Canal. “I’m too big,” said von Zehle. “Get down here.”

At the top of the shaft on the third floor, Valentine took off his flak jacket, laid down his weapon, and put on his gloves. Having already treated the injured downstairs, he was almost out of supplies. All that he had left in his medical kit were three IVs, two vials of morphine, and five bandages. Von Zehle pulled himself out of the pit, and the two exchanged biographical notes. “Well, at least two people in Baghdad have done this type of work before,” Valentine said. Looking down into the dark rubble tunnel below, he said, half-joking, “We should be just fine now.” Von Zehle nodded. “What I wouldn’t do for the right equipment right about now,” he said. It was around 5:30 p.m., more than an hour since the attack. Davie tried to keep Vieira de Mello informed about the progress of the rescue. A U.S. Army medical sergeant named Eric Hartman arrived. “Eric is an expert in this type of recovery,” Davie told him. “He has an expert team and engineering equipment.” Vieira de Mello placed his hope in this new-found expertise. He said he could hear Hartman and called back to him several times, “Eric, can you hear me?” Hartman could not hear him, perhaps because he was turned in the opposite direction or because the noise at the site had grown too loud with the arrival of the helicopters above. “Sergio, we are trying to find a way to you from two directions,” Davie said. Vieira de Mello responded simply, “Jeff, please hurry.”

When Larriera approached the back of the building, Vieira de Mello’s bodyguards and U.S. soldiers at the base of the rubble attempted to keep her away, roughly grabbing her by the arms and trying to deposit her back behind the cordon rope. She was stunned to see how few people were digging in the rubble itself. Most of the soldiers had their backs to the rubble and were more focused on keeping people away from the crime scene than on extracting those trapped within the pile. Larriera begged the U.S. soldiers manhandling her to start digging. “Let’s use the mangled metal lying around,” she tried. “Or what about your helmets?” As she bent over at the base of the enormous pile, she dug pathetically with her hands. “I thought maybe if I was digging, even if I looked like a fool, they would get the idea,” she recalls. But the soldiers were following orders and continued to face away from the Canal Hotel. Several cameramen filmed the rescue, and she pleaded with them to join in. “Please help,” she shouted. “Don’t film! Help!”

The closest thing to civilian leadership on the scene came from Patrick Kennedy, Bremer’s chief of staff, who had arrived with Colonel Sabal forty-f ive minutes after the bomb struck. As they entered the area, Iraqi civil defense corps guards were trying to get in, but the U.S. soldiers who had erected the cordon were trying to keep them back.“I’ve got to get them in,” Kennedy told Sabal. “We trained them. We can’t just leave them out there. This is their country.” Kennedy succeeded in clearing their entry and then ran into Captain Kuhner. “Captain, what do you need?” Kuhner told him: “I need a backhoe, shoring materials to prop up the building, a C truck with a jackhammer on one end, cranes, earth-moving equipment.” Kennedy said he would do what he could. He radioed Bremer’s military aides and requested further assistance.

Kuhner had already sent a group of military police into town to commandeer Iraqi fire brigades. And to his delight, at around 6 p.m., ninety minutes after the blast, two gleaming red fire engines pulled into the Canal complex. Kuhner and a sergeant raced toward them. When they tugged at the hatches, however, they realized that the storage cabins were bolted shut. And the vehicles had arrived with drivers but without firemen. When Kuhner asked the driver of one of the fire engines where the keys were, the driver shrugged. “Somebody find me bolt-cutters,” Kuhner ordered. When the bolt-cutters arrived, he and the sergeant hustled to opposite sides of the fire truck and sliced through the iron locks. The hatches swung open. But when Kuhner looked inside, all he saw were the legs of his colleague on the other side. The equipment—sledgehammers, ladders of various lengths, Sheetrock pullers, crowbars, rappelling rope, and backboards to transport the injured—was missing. “Where the hell is everything?” he raged at the Iraqi driver. The driver shrugged. “Ali baba,” he said, using the derogatory Iraqi phrase for “thief.” In yet another consequence of the Iraqi looting spree, the ali baba had run away with the fire department’s gear.

Back in Geneva, Jonathan Prentice, fresh off the celebration of his wedding anniversary in Beirut, had gone for a run in the morning and stopped in town for a haircut. As he walked home, he dropped by the security hut at his regular place of employment, the Palais Wilson, home of the Office of the UN High Commissioner for Human Rights. The security guards looked at him like they were seeing a ghost. “What are you doing here?” one asked. “I’m on holiday,” he said cheerily.“Haven’t you heard?” a guard said. “There’s been a bomb at the Canal.” Prentice’s stomach dropped, but he quickly assured himself that this was an incident like other incidents. He scrambled inside the palais and joined his colleagues who were crowded around a television in Vieira de Mello’s office on the top floor. When CNN showed the size of the rubble pile that used to be Vieira de Mello’s office, Prentice gasped. He telephoned a friend at UN Headquarters in New York every half hour for what was left of the day.

Alain Chergui, Vieira de Mello’s trusted bodyguard who had left Iraq on August 14 with Prentice and Ray, was in Bali. The Iraqi dry cleaners had stained some of his clothes, so he spent the afternoon shopping. He returned to his hotel and turned on the television, where he saw news of the attack and glimpsed the back of his colleague Pichon’s bald head. He desperately telephoned the close protection team members in Baghdad. He reached a Swedish bodyguard and attempted to take charge from Bali. “We’re going to need blood,” Chergui said. “He’ll need a transfusion.” The Swede sounded as though he had lost hope. “We can’t get blood here,” he said. “It’ll be too late.”

With the bomb Salim Lone suddenly became the television face of the UN mission. In his multiple appearances on CNN, Lone, whose head was bandaged, delivered unpolished, flustered comments. He often seemed to be talking more to himself than to his interlocutors. “It is quite unspeakable to attack those who are unarmed. You know, we are not protected. We are easy targets. We knew that from the beginning, but we came nevertheless, knowing there was a risk, but every one of us wanted to come and help the people of Iraq, who have suffered for so long. And what a way to pay us back.”

10

An hour later Lone appeared on CNN again: “There are also some wonderful Iraqis who died here today, so it just wasn’t us,” he said, noting that the UN death count had already reached thirteen. “It is such a devastating experience to be so hated, when all you’re trying to do is help. I mean, every one of them who died was here as a humanitarian.” The only note of optimism he sounded concerned the efforts being made to rescue Vieira de Mello. “It’s just been agonizing. We’re just making every effort to pull him out, and we have not been able to do it so far. But we think we have made some very good progress, and he might soon be removed from the rubble.”

11 Rumors were flying among survivors, U.S. soldiers were offering speculative words of reassurance, and Lone was repeating the hopeful words on CNN.

A frustrated Captain Kuhner had nothing to show for his attempt to requisition Iraqi fire rescue equipment. He moved back to the rear of the building and made himself the primary barrier between Larriera and the pile. She thought that if Kuhner understood who was under the rubble, he might get U.S. soldiers to do more. “Sergio Vieira de Mello, the SRSG, is buried right under there,” she said. Kuhner stared back blankly. “The Special Representative of the Secretary-General of the UN is buried there,” she tried. Again Kuhner was unmoved. “The UN boss is buried there,” she said “Kofi Annan’s envoy, the equivalent of General Sanchez.” Kuhner urged Larriera to go to Tent City with the other survivors. “You are only going to make it more difficult for us,” he told her. Larriera would not be dissuaded. “No, I’m not going,” she said. “You can’t make me.” The more patronizing the soldiers were with her, the more she had to struggle to maintain her calm.

Over Kuhner’s shoulder Larriera saw that Davie, Pichon, and Salamé seemed to have found a way to communicate with Vieira de Mello from a hole on top of one pile of rubble. She feigned an intention go back to Tent City, which caused Kuhner to relax his grip, and then she broke free and managed to tear past him. He pursued her but was weighted down by his heavy armor.

At the rear of the building Vieira de Mello seemed to be able to hear people through two separate crevices between the concrete slabs. The first was fifteen feet up the rubble, where Davie had held Loescher’s hand. The second point of entry was about fifteen feet to the right and slightly lower, near the right rear corner of the building. It was there that Larriera saw Davie, Pichon, and Salamé apparently speaking to Vieira de Mello. They could not reach him, but when Davie squeezed into the crevice up to his waist, he could see one of his boss’s arms. Vieira de Mello’s voice was able to carry through the crevice to where they were. He could hear and be heard. In Davie’s judgment, if the UN and U.S. officials could just lift the outside collapsed slab a few inches or pull rubble away from this gap, they could reach him.

In order to speak with Vieira de Mello, which Larriera was determined to do, she needed to scale the rubble. Once she escaped Kuhner’s grip, she still met resistance from her UN colleagues. Pichon, who was lower down in the rubble than Salamé and Davie, tried to wave her away, but she persisted. “What would you do if it was your wife under there?” she asked. Salamé, above, said, “Carolina, you’ll cause the rubble to collapse on top of Sergio.” But she would not be deterred. “You’re much heavier than I am, Ghassan,” she shouted. She climbed the rubble quickly, terrified that the U.S. soldiers would try to pull her down from behind. In so doing, her sandals got stuck in the mud, and she felt her skirt get caught on a piece of steel rebar. She kept moving up the rubble and grimaced as the back of her skirt tore off, leaving her underwear exposed from behind.

She stared up at one final steep flat block of concrete between her and Salamé. She cried up for help, and he extended his hand, pulling her up to where he was crouched on the pile. For the next five minutes she squatted down atop the rubble and poked her head inside the gap. “Sergio, are you there? It’s me,” she said in Spanish. “Carolina, I am so happy . . . you are okay,” he answered, relieved by his first confirmation that she had survived. “How are you feeling?” she asked. “My legs, they are hurting. Carolina, help me,” he answered. “Be still, my love,” she replied. “I am going to get you out of there.” But realizing that a far more industrial rescue effort was needed and feeling as though she was the only one possessed with frantic urgency, she told him that she had to leave temporarily to get proper help. “I am coming back very soon,” she said. “Volve rápido, te amo,” he replied. “Come back quickly, I love you.”

Soon after news of the blast hit London, the BBC posted a discussion page, “Baghdad UN Blast: What Future for the UN?” A diverse range of comments went up, slamming the U.S. occupation, lamenting the silence of moderate Muslims, and deploring the attack. The tenth comment on the site came from Argentina:

My sister was in the building, she works for the UN, her name is CAROLINA LARRIERA. PLEASE, any notice you have about her, send a mail. Someone notice me that she appears in the BBC TV broadcast. THANK YOU.

Pablo Larriera, Argentina

A UN staffer in Kosovo quickly posted a message, informing Larriera’s thirty-two-year-old brother that she was safe. “Apparently,” the UN official wrote, “she was seen on television trying to enter the site after the bomb had exploded.”

12

With Kofi Annan and his deputy Louise Fréchette on vacation and absent from New York, Iqbal Riza, the secretary-general’s chief of staff, was the most senior UN official at Headquarters. He did not make calls to Secretary Powell, National Security Adviser Rice, or any other senior U.S. official to expedite the rescue because, from CNN, it looked, in his words, “as if all that could be done was being done.” But it was left to UN spokesman Fred Eckhard to interface with the press. At 12:01 p.m. in New York he read Annan’s first statement on the attack, from Finland. The secretary-general denounced the “act of unprovoked and murderous violence against men and women who went to Iraq for one purpose only—to help the Iraqi people.” Pressed by reporters to say what implication the attack would have for the UN, Eckhard said he had few doubts that “we’re going to stay the course.”

13 Responding to charges that the UN had been lax with its security, he said, “The security is the responsibility of the Coalition partners. We depend on the host country for our security wherever we work in the world.”

14The chaos at the Canal Hotel on August 19 stemmed in part from the novelty of the occasion. Only one large attack on a civilian target had occurred before in Iraq, and that was just twelve days before, the August 7 attack on the Jordanian embassy. But the bulk of the confusion was the result of multiple, dueling command structures and improper planning that gave rise to insufficient capacity. Wherever the United Nations set up operations around the world, it depended on local authorities for emergency services. If the UN Headquarters in New York City were hit, New York firemen and police would rush to the scene and FBI officers would investigate. In Baghdad, just as the UN had relied upon U.S. and Iraqi forces for protection, so too the UN now relied upon both for rescue.

But when it came to rescue in Iraq, it was unclear just who constituted the “local authorities.” Were they American or Iraqi? The Coalition had become the “provisional authority,” and it was an American civilian, not an Iraqi fireman, who actually ran the Iraqi fire department. U.S. soldiers at the Canal did not know what equipment the Iraqi fire department had, where the equipment was located, or who had the authority to summon it. If Americans were in charge, should U.S. civilians or military officers command the scene? Again, had the attack occurred in the United States, the division between civilian and military responders would have been clear. Even when the Pentagon was struck on September 11, 2001, it was the Arlington, Virginia, fire chief who served as the on-site commander for ten days. Even the most senior Defense Department officials technically answered to him. But in Iraq, while it was civil affairs officers who had rescue experience, they didn’t have the rank to issue instructions to their superior officers. “There was no one evidently in charge,” recalls Patrick Kennedy, Bremer’s chief of staff, who himself lacked any line authority over the U.S. military.

So the UN wasn’t in charge, the Iraqi fire department wasn’t in charge, and the U.S. Army tried to be in charge, but, in Valentine’s words, “they hadn’t dealt with a blown-up building before. They didn’t know what to do.” For Valentine and von Zehle, two of the few men on the scene who had experience undertaking rescue missions, descending into the shaft was something of a relief. At least they would henceforth be masters of their own destinies.

Desperate to do anything she could to help her fiancé and stunned by the lack of urgency and the primitive state of the rescue, Larriera left the rubble and went to Tent City to beg for help. She tried to get the UN’s most senior officials involved. The highest-ranking UN official at the Canal that day, apart from Vieira de Mello, was under-secretary-general Benon Sevan, who was visiting from New York. But Sevan did not return to the Canal once he reached Tent City. As Larriera prodded him to take charge, he refused even to make eye contact with her. Lopes da Silva, Vieira de Mello’s deputy, seemed to be constantly on the phone to New York. He had paid just one visit to the rear of the building. Bob Adolph, the head of security, also was in Tent City. “Who is in charge?” Larriera pleaded, begging one of the men responsible for security to go to the back of the hotel. “The soldiers there have no idea who is under the rubble! Sergio is dying!” Both men attempted to assure Larriera that the maximum was being done. “We’re trying to get him out, Carolina,” Lopes da Silva said. “You have to calm down.” As she chased after him, he turned his back, saying, “The Americans are in charge.”

Having failed to get help in Tent City, Larriera attempted to make her way once again to the rear of the Canal. But by this time the army had established an inner cordon of soldiers, sandbags, and trucks, preventing UN officials and nonspecialist U.S. soldiers from reaching the back of the building. Larriera paced the length of the inner cordon, pleading with U.S. soldiers to let her pass, but she was blocked. Although she had promised Vieira de Mello she would return, she could not do so.

Bremer might have helped streamline the multiple lines of command, but he did not arrive at the Canal Hotel until dusk. Since Eckhard had taken a swipe at the security provided by the United States, Bremer asked Kennedy and Sabal to find out what protection U.S. forces had offered. Sabal wrote Bremer’s query in his notebook: “How do we answer the question of why we were unable to provide security?” Sabal scribbled next to it: “Lack of troops.” While at the Canal, Bremer spoke to the media. “My dear friend Sergio is somewhere back there,” he said. “It may well be that he was the target of this attack.” From Bremer’s remarks, it was clear he believed that pro-Saddam loyalists were responsible. “These people are not content with having killed thousands of people before,” he said. “They just want to keep killing and killing and killing. And they won’t have their way.”

15 He was sure that, despite the attack, the UN would stay. “I’m absolutely certain that the United Nations, instead of cutting and running, will stand and stay firm, as indeed the Coalition will.”

16

Back in the United States, President Bush was on vacation at his ranch in Crawford, Texas. So many journalists were away that New York

Newsday columnist Jimmy Breslin called August 19 a day when “a congressman could commit homicide and not make the news.”

17 Bush received word of the attack while playing golf. Initially he kept playing, but after an hour he returned to his ranch and issued a statement at 7:05 p.m. Baghdad time. “The Iraqi people face a challenge, and they face a choice,” the president said. “The terrorists want to return to the days of torture chambers and mass graves. The Iraqis who want peace and freedom must reject them and fight terror.”

18The UN lacked any in-house capacity to determine who had carried out the attack or to bring the plotters to justice. But the FBI response in the immediate aftermath of the attack was impressive. When the bomber struck, Thomas Fuentes, who ran the FBI unit in Iraq, was at Baghdad airport, and he used GPS to guide him and a team of agents to the blast. Within an hour of the explosion nearly two dozen agents had descended on the crime scene to begin sifting through the rubble to gather evidence. This was the first attack in which U.S. civilians had been among those targeted, so the FBI’s jurisdiction was uncontested.

When Fuentes arrived, Iraqis were crowding around the army’s outer cordon rope, calling out the names of loved ones who worked in the building. Iraqi teenagers had come with coolers to sell Pepsis to the crowd.

19 The spinal hospital, which was on the opposite side of the access road from the Canal, had also been badly damaged by the blast. Ten of its patients had been injured, and the others, many of whom were survivors of Iraq’s three wars, were petrified. Some were trapped for more than an hour under the collapsed roof, while others, who were barely dressed, were rolled outside in their wheelchairs and left sitting, carrying their catheter bags, in the scorching sun.

20On the day and evening of the nineteenth, the FBI analysts avoided the rear of the Canal, where rescue efforts were proceeding, and instead fanned out in a lot beside the spinal hospital. Three hundred feet from the point of impact, the lot was layered with a wide variety of debris: shards of metal from the bomber’s truck, rubble from the cement walls, and multiple body parts belonging to the driver himself. Fuentes’s team included one experienced bomb-blast expert, who was in the country to help investigate the Jordanian embassy attack, and he offered on-site training to the others so they could efficiently assemble the forensic clues. The explosion had sent pieces of evidence in hundreds of directions, and they would eventually be retrieved from a five-square-mile area. In but one testament to the scale of the strike, the crater from the explosion, which was around three and a half feet in diameter and around five feet deep, could have easily fit a Volkswagen.

Valentine, the New York medic, had an even bigger crater to navigate. “Keep your eyes closed, folks,” he said as he rappelled downward into the shaft. He was worried about the cascading debris. “I’m coming down!” Loescher answered him, saying, “Good, I need your help.” But Vieira de Mello was silent. In his twenty-eight-year career the American EMT had dealt with multiple collapsed buildings and had once extricated a woman trapped under a crane in New York City. But although he had already served eleven months in Afghanistan and four months in Iraq, this was his first wartime civilian rescue effort.