Foreword

by ELIZABETH GILBERT

This cookbook has been around my family a lot longer than I have. At Home on the Range was first published in 1947, back when my father—now a grey-bearded man in flannel shirts—was a towheaded toddler in droopy pants. The book was dedicated to my Aunt Nancy, whom the author described as a five-year-old child already in possession of the “two prime requisites of a good cook: a hearty appetite and a sense of humor.” (Nancy is still in possession of both those fine qualities, I am happy to say, but she is now a grandmother.) The copy of the cookbook that I inherited belonged to my own grandmother, our beloved and long-gone Nini, whose penciled notes (“Never apologize for your cooking!”) are still in the margins. The book was written by her mother—my great-grandmother—who was a cooking columnist for the Wilmington Star, and who died of alcoholism long before I was born. Her name was Margaret Yardley Potter, but everyone in my family called her Gima, and until this year, I had never read a word of her writing.

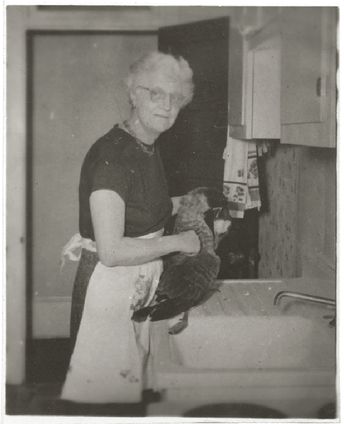

Of course, I’d seen the book on family bookshelves, and had certainly heard the name Gima mentioned with love and longing, but I’d never actually opened the volume. I’m not sure why. Maybe I was busy. Maybe I was prejudiced, didn’t expect much from the writing: the original jacket photo shows a kindly white-haired woman with set curls and glasses, and maybe I thought the work would reflect that photo—dated and ordinary, JELL-O and SPAM. Or maybe I am just a fool, willing to travel the world in pursuit of magic and exoticism while ignoring more intimate marvels right here at home.

The author photo from the first edition.

All I can say is that I finally picked up Gima’s cookbook this spring at the age of forty-one, when I found it at the bottom of a box, which I was finally unpacking because I was finally settling into the house where I hope and pray to finally stay put. I cracked it open and read it in one rapt sitting. No, that ’s not entirely true: I wasn’t really sitting, or at least not for long. After the first few pages, I jumped up and dashed through the house to find my husband, so I could read parts of it to him: Listen to this! The humor! The insight! The sophistication! Then I followed him around the kitchen while he was making our dinner (lamb shanks), and I continued reading aloud as we ate. Then the two of us sat for hours over the dirty dishes, finishing a bottle of wine and taking turns reading the book to each other by candlelight.

By the end of the night there were three of us sitting at that table.

Gima had come to join us, and she was wonderful, and I was in love.

What you have to understand about my great-grandmother, first and foremost, was that she was born rich. Not stinkin’ rich—not Park Avenue rich, or Newport rich—but late nineteenth-century Main Line Philadelphia rich, which was still pretty darn rich. I tend to forget that we ever had that strain of wealth and refinement in our family (probably because both were long spent by the time I arrived) but—decidedly unlike her descendants—Gima grew up with sailboats and lawn tennis, white linens and Irish servants, social registers and debutante balls.

The young Margaret Yardley was not a beauty. That would ’ve been her little sister, Elizabeth (for whom I was named.) A family visitor, introduced to both girls when they were in their teens, let his eyes rest on my great-grandmother and said, “Well, you must be the one who cooks.” Well, yes, she was the one who cooked—and she also happened to be the charming and popular one. With such nice credentials, she probably could’ve married just about anyone. For reasons lost to history, she chose to marry my great-grandfather Sheldon Potter—a charismatic Philadelphia lawyer full of brains and temper and narcissism, who was witty but lacerating, sentimental but unfaithful, who’d passed the bar at age nineteen and could quote Herodotus in Greek, but who never developed a taste for work. (As one disapproving relative later diagnosed him, “He was too heavy for light work, and too light for heavy work.”)

Sheldon Potter did, however, develop a taste for fine living and for serious overspending. As a result, Gima slid deeper and deeper into reduced circumstances with every year of her life. As she relays (uncomplainingly!) in the first pages of her cookbook, over the course of her marriage she was “shuttled financially and physically between a twelve-room house in the suburbs, a four-room shack in the country, numerous summer cottages, and a small city apartment.” She passed the lean years of World War II on “an isolated and heatless farm on Maryland’s Eastern Shore,” which was probably the furthest imaginable cry from her classy Edwardian upbringing.

Listen, she made the best of it. For one thing, her financial troubles were not entirely Sheldon’s fault: Gima was quite the spendthrift herself, and she faced life with a Jazz Age sensibility that can best be summed up in one gleeful, reckless, consequence-be-damned word: Enjoy! Moreover, she had an instinct for bohemian living—maybe even a preference for it, and that instinct informs the winningly informal tone of At Home on the Range. While she admits, for instance, that “there is no substitute for either good food or a comfortable bed,” she submits that pretty much everything else in the material world can be substituted, or improvised, or gone without, or cobbled together from junk-store treasures. Books can be borrowed, wildflowers can be picked from roadside ditches, barrels can be transformed into perfectly good little tables, orange crates make for excellent chairs, cheap onions can replace expensive shallots without anyone ’s tasting the difference, and there ’s no need whatsoever to be ashamed of a kitchen that resembles “an old-fashioned tin peddler’s cart.” All your guests really need from you, Gima assures us, is your warm welcome, plenty of good food, and a steady supply of ice for cocktails. Provide that, she promises, and “a world of friends will beat a path to your door.”

So she did provide, and so a world of friends did beat a path to her door, but it should not be inferred that her life was necessarily easy just because her houseguests adored her. Married to a man whom my father describes as “impossible,” constantly in debt (sometimes slipping out of foreclosed homes just ahead of the sheriff ’s arrival), struggling with the alcoholism that would periodically land her in psychiatric clinics and grim hospital wards, my creative but constrained great-grandmother was not the first or the last woman in the history of female hardship to take refuge in food.

Gima in her garden.

Or rather, I should say, she took refuge both in food and in writing, because the voice that emerges on these pages is a literary delight as well as a culinary one. Gima doesn’t just list her recipes here, she tells her recipes, with wit and self-confidence that make her sound like a cross between Dorothy Parker and M.F.K. Fisher. (Don’t overthink orange marmalade, she assures us in one typically bright passage: “Constant stirring and average intelligence is really all that ’s necessary.”) Gima was also a food sensualist, a quality all too often missing in American cookbooks from that era. Not only does she carefully explain how to bake a perfect loaf of bread, but just as the loaf is coming out of the oven she adds, “And if you can resist cutting off a big warm piece and spreading it thickly with butter, you’re not the girl I think.”

But what strikes me most, reading Gima’s cookbook, is that she was so far ahead of her time. At Home on the Range was published right between the end of World War II and the onset of 1950’s—right at that unfortunate moment in American culinary history when our country was embarking on its regrettable love affair with convenient and processed foods, with canned goods and electrical appliances, with powdered mashed potato mixes and easy-breezy marshmallow salads. Gima was having none of it. Instead, she encouraged her readers to explore, to dare, and most of all, to do it by hand. What follows is only a partial list of the recipes she was cheerleading while the rest of the country tucked into Birds Eye frozen peas and quick-heat TV dinners:

BRAINS WITH BLACK BUTTER

CHICKEN LIVERS FOR SIX

BEEF AND KIDNEY PIE

TONGUE

EELS (which she reports having first discovered during wartime meat shortages, and which, she believes, are so delicious they must be “devoured in a silence almost devout”)

TRIPE (which must be hand-scrubbed “like a bath towel” before cooking—a process that is, she swears, “more fun than it sounds”)

COCKSCOMBS WITH WINE (collected in buckets from puzzled local poultry farmers)

BOILED ROCK FISH (hand caught, and then hand-sewn into one of your husband’s old undershirts with a half-dozen other fresh ingredients)

WILD GRAPE JELLY (“picking the fruit yourself beneath a blue fall sky is half the pleasure”)

ANTIPASTO WITH FRESH SARDINES

SCRAPPLE

CALVES’ HEAD CHEESE (a “grand hot-weather snack!”)

MUSSELS (which she bemoans as being “an insufficiently known delight” on this side of the Atlantic)

And on it goes, making me wonder who was she writing this for?

These days, I have about twenty friends who would happily scrub raw tripe like a bath towel, or eat cockscombs straight off a freshly scalped rooster, but this is now, this is 2012, when unshrinking foodie exploration is all the rage. Gima, on the other hand, was writing at the dawn of the baby boom, when it wasn’t. This is perhaps why her book only came out in one edition. Maybe people weren’t yet ready for her appetites. Like mussels in mid-twentieth-century America, maybe she herself was doomed to be an insufficiently known delight.

But in both cases (with bivalves and great-grandmothers alike) better late than never, right? And Margaret Yardley Potter is certainly worth getting to sufficiently know now. Almost a generation before Julia Child, my great-grandmother was not merely a terrific cook, but also a dogged food reporter, an intrepid food explorer, and a curious food historian. She wasn’t afraid to wander back into the kitchen of some ritzy hotel or swanky transatlantic ocean liner to bribe a sauce recipe out of a flattered French chef. But she also managed—between contractions—to extract a fantastic pickle recipe from the friendly nurse who helped deliver her first child.

And speaking of motherhood, when Gima was hugely pregnant with my grandmother (this would be 1918), she was eating her way through an Italian neighborhood in Philadelphia one day when she discovered “a warm, brownish red pastry” called “Italian tomato pie, or pizza,” and thereupon convinced “the ancient proprietress” of the shop to teach her how to make it. How many other respectable—and knocked up!—ladies from good Main Line Philadelphia families were wandering around immigrant neighborhoods in 1918, not only eating pizza with the denizens, but learning how to make it at home? She also learned how to make fricasseed rabbit from a Pennsylvania Dutch farm woman, baked beans from a handyman’s wife in a Maine fishing camp, and quick tea cookies from a handwritten cookbook she’d bought at a rural yard sale. (The elderly farmer who sold it to her claimed the book had been “his grandmom’s mom’s”—which means, as of today, that recipe is nearly two hundred years old. You can find it on page 121, and it’s lovely.)

Gima plucking a goose.

It’s impossible to read all this lively writing and culinary exploration without wondering, My god, what might she have become? In a different time or place, what might Gima have made of all her curiosity and passion and talent? And that is the sad question that leads me to the story about my great-grandmother and Paris. Or, rather, the story that is almost about Paris.

The tale goes like this: In the mid-1930s, Margaret Yardley Potter walked out on her impossible husband Sheldon. She’d had enough of him. There was talk of a divorce. I don’t know how close they came to actually filing papers, but she definitely moved out and lived on her own for a while. (I suspect she may be referring to that episode when she writes in her cookbook that every woman should know how to mix her own cocktails, in case her husband is indisposed, or in case the hostess in question “lives alone and likes it.”) In any case, Gima left her husband and formulated a plan—or maybe we should call it a dream. She would take her teenage daughter and relocate to Paris, where they would live with her Uncle Charlie, who was an established portrait painter over there. (Her college-age son would stay back in the States and finish his schooling.)

According to family lore, there was something scandalous in Uncle Charlie’s past that had probably sent him over to Paris in the first place. There is talk that he might have had an affair with a married woman, which had driven him out of polite Philadelphia society. Whatever his transgressions, my great-grandmother cherished him. Uncle Charlie, in fact, makes several appearances in this cookbook, most notably when Gima relates visiting him in France as a young woman and eating a “thrilling lunch” in his lofty studio—“disappointingly empty of beautiful undraped women”—where she learned, by the end of the afternoon, how to mix a perfect vinaigrette. She also, quite obviously, learned from Uncle Charlie how to love France, and she always wanted to return there. You need only read two pages of her book to recognize that she belonged in France: it’s where her sensibilities’ standards could have been met, where her talents could have been recognized, and where her confrères could have been found. Imagine the people she might have encountered there! Imagine the food she might have eaten! The books she might have written!

Well, she almost moved there, anyhow. I still have the passport photo of her and my young grandmother, seated together in silk dresses and perfect hairdos, looking regal and sophisticated and absolutely ready to hop on the next ocean liner… but they never went. Instead, Gima returned to her impossible husband, with her passport and daughter in tow. She remained with Sheldon until she died in her early sixties. He, on the other hand, remarried and lived quite happily until the age of ninety-nine and three quarters—drinking and eating and smoking and reading with rather impressive gusto right till the end. I was sixteen years old when he died, so I knew my great-grandfather well. He awed and delighted me, and gave me challenging reading assignments whenever I came to visit. I have always believed that his inspired bookishness was one of the reasons I became a writer. I didn’t realize until reading At Home on the Range that Gima may also have been a contributing factor to my vocation—that there may be such a thing as a Family Voice, and that I may have been lucky enough to have inherited some of mine from Margaret Yardley Potter.

Ultimately, I don’t know why Gima went back to her husband instead of pursuing her dream of Paris. Nobody knows. Maybe she didn’t have the cash or the courage to go. Or maybe she just missed him. I can tell you this much: every single reference she makes to that man in her cookbook is affectionate—but credibly affectionate, by which I mean that she writes of her husband fondly, but not without undertones of undisguised domestic tension. It sounds like a real marriage, in other words. A good example is her description of their kitchen blackboard, which, she reports, is frequently chalked over with teasing spousal messages like “Where did you put the bottle opener, you bum?” Cute, yes—though also telling, on many levels.

Margaret and Madeleine Potter.

Whatever her reasons, she went back home. Something in me wishes she hadn’t, even though it would’ve changed our family history so dramatically that some of us—me, for instance—would not exist. It’s a silly wish. It’s always a naive instinct to want to rewrite history, anyhow, and there’s probably something particularly naive about my belief that Gima could’ve had a happier and healthier life as a divorced woman in Europe. The fact is, she was an alcoholic, and nobody’s alcoholism ever got cured by simply changing locations. (Certainly nobody’s alcoholism ever got cured by moving to Paris in the 1930s.) But still. You can imagine how she would have been in her element there. And if there is a heaven for cooks—and my great-grandmother insists in these very pages that “surely there is one”—then I would like to believe that Gima is in that heaven, and that it bears an uncanny resemblance to the country of France.

Gima is still dearly missed within our family.

She died in 1955, but my relatives still get emotional when they talk about her. She was, it is consistently proclaimed, the most wonderful woman you ever knew. The funniest, the brightest, the most marvelous, the most loving, the center of every party. She could make a Christmas celebration pop like nothing you ever saw. My dad’s happiest memories of childhood were Christmases spent with Gima, when they would make edible ornaments by baking a loop of string straight into the cookies—the recipe is in this book!—and then they would hang the cookies directly on the tree… and then the family dogs would knock over the tree to get at the cookie-ornaments, but nobody seemed to care. Indeed, “nobody seemed to care” is how a lot of stories about my great-grandmother’s legendary parties end: she didn’t mind the furniture getting thrown around the room a little bit, it appears, as along as everyone was having fun.

She was certainly a warm and generous woman, as evidenced by her core tenets regarding hospitality, which include “Try not to forget your friends’ birthdays,” or “Be lavish with the coffee,” or “Try not to let those unexpected guests feel that you are embarrassed by their sudden appearance—half the time, they are a little embarrassed themselves.” I found myself quite moved by the chapter “Open Your Mouth and Say ‘Ah-ha,’” where Gima lists recipes that are good for sick friends who are stuck in the hospital. (These range from cinnamon buns or simple deviled eggs to—on the happy night before the patient’s release—a smuggled-in bottle of champagne and a celebratory tin of caviar.) Ask yourself if you have ever seen another gourmet cookbook in which recipes are included for hospitalized friends. And it goes beyond mere food! If the patient is a child, my great-grandmother further suggests, be sure to bring him a little goldfish in a glass bowl, or one of those tiny turtles you can buy at any pet store; this will go far in easing a sick child’s boredom and loneliness. When I think of all the time Gima herself spent alone in hospitals and institutions, these pages feel only more poignant. I just hope somebody in her life was bringing her cinnamon buns and baby turtles.

So her loss is still felt keenly by all my relatives. But she outlived herself in some ways, if that makes sense. What I mean is—some parts of herself have outlasted other parts of herself, and can still be found, scattered among us.

Her kitchen has outlived her: My cousin Alexa has its contents—down to the least serviceable utensil—in her house in Baltimore.

Her recipes have outlived her: I grew up eating Gima’s chutney and Gima’s pickles, prepared by my Midwestern mother, who never met the woman, but who fell in love with the cookbook.

Her name has outlived her: my Uncle Nick named his daughter Margaret, in honor of his irreplaceable grandmother.

Her humor has outlived her: for instance, whenever we play cards in our family, we still say, “Help yourself to the stewed fruit,” which was the catchphrase Gima delivered every time she got dealt a lousy hand.

And her passions have outlived her, still manifesting themselves quite firmly, four generations later, through the pursuits and aspirations of her female descendants. Among her six great-granddaughters, three of us write for a living, one of us runs a restaurant, one of us is a hostess worthy of any recipe in this book, two of us are wizards at cards, two of us are trained historians and three of us found a way to live overseas. All of us love a good party. Gima also has two preteen great-great-granddaughters, who are not only charismatic and literary, but in whom the “prime requisites” of—yes!—“hearty appetite and sense of humor” have come down the pike utterly intact.

What I’m saying is, if you are influential enough and beloved enough, it turns out you can stick around for quite a while after you die.

When, in preparation for writing this essay, I asked my family for memories of Gima, my uncle Nick sent this email: “Christmas 1969. You are zero years old. Dad and Mom and me and Nancy your parents and you two kids are all squeezed into that little dining room on Moore Avenue, and there are candles, and John and I are back from the war, and everything’s just wonderful. Then your father says, ‘This would all be perfect if only Gima were here.’ And Mom sighed and said, ‘Well, that’s that.’”

Well, that is that.

We all wish she could’ve stuck around a lot longer, but what can you do? As Gima herself might’ve said, “Help yourself to the stewed fruit.” It is what it is, folks. She stayed as long as she could. But what she left behind was something quite remarkable. My hope, with this new edition of her cookbook, is that in our generation she will finally find her readers, her peers, her admirers, the culinary confrères she always deserved.

On Gima’s behalf, then, it is my great pleasure to make this introduction.

Enjoy.