Fire dancers.

Since the Polynesians ventured across the Pacific to the Hawaiian Islands 1,000 years ago, these floating jewels have continued to call visitors from around the globe.

Located in one of the most remote and isolated places on the planet, the islands bask in the warm waters of the Pacific, where they are blessed by a tropical sun and cooled by gentle year-round trade winds—creating what might be the most ideal climate imaginable. Mother Nature has carved out verdant valleys, hung brilliant rainbows in the sky, and trimmed the islands with sandy beaches in a spectrum of colors. The indigenous Hawaiian culture embodies the “spirit of aloha,” an easy-going generosity that takes the shape of flower leis freely given, monumental feasts shared with friends and family, and hypnotic Hawaiian melodies played late into the tropical night.

Visitors are drawn to Hawaii not only for its incredible beauty, but also for its opportunities for adventure. Go on, gaze into that fiery volcano, swim in a sea of rainbow-colored fish, tee off on a championship golf course, hike through a rainforest to hidden waterfalls, and kayak into the deep end of the ocean, where whales leap out of the water for reasons still mysterious. Looking for rest and relaxation? You’ll discover that life moves at an unhurried pace here. Extra doses of sun and sea allow both body and mind to recharge.

Hawaii is a sensory experience that will remain with you, locked in your memory, long after your tan fades. Years later, a sweet fragrance, the sun’s warmth on your face, or the sound of the ocean breeze will deliver you back to the time you spent in the Hawaiian Islands.

The First Hawaiians

Throughout the Middle Ages, while Western sailors clung to the edges of continents for fear of falling off the earth’s edge, Polynesian voyagers crisscrossed the planet’s largest ocean. The first people to colonize Hawaii were unsurpassed navigators. Using the stars, birds, and currents as guides, they sailed double-hulled canoes across thousands of miles, zeroing in on tiny islands in the center of the Pacific. They packed their vessels with food, plants, medicine, tools, and animals: everything necessary for building a new life on a distant shore. Over a span of 800 years, the great Polynesian migration connected a vast triangle of islands stretching from New Zealand to Hawaii to Easter Island and encompassing the many diverse archipelagos in between. Archaeologists surmise that Hawaii’s first wave of settlers came via the Marquesas Islands sometime after a.d. 1000, though oral histories suggest a much earlier date.

Over the ensuing centuries, a distinctly Hawaiian culture arose. Sailors became farmers and fishermen. These early Hawaiians were as skilled on land as they had been at sea; they built highly productive fish ponds, aqueducts to irrigate terraced kalo loi (taro patches), and 3-acre heiau (temples) with 50-foot-high rock walls. Farmers cultivated more than 400 varieties of kalo, their staple food; 300 types of sweet potato; and 40 different bananas. Each variety served a different need—some were drought resistant, others medicinal, and others good for babies. Hawaiian women fashioned intricately patterned kapa (barkcloth)—some of the finest in all of Polynesia. Each of the Hawaiian Islands was its own kingdom, governed by alii (high-ranking chiefs) who drew their authority from an established caste system and kapu (taboos). Those who broke the kapu could be sacrificed.

The ancient Hawaiian creation chant, the Kumulipo, depicts a universe that began when heat and light emerged out of darkness, followed by the first life form: a coral polyp. The 2,000-line epic poem is a grand genealogy, describing how all species are interrelated, from gently waving seaweeds to mighty human warriors. It is the basis for the Hawaiian concept of kuleana, a word that simultaneously refers to privilege and responsibility. To this day, Native Hawaiians view the care of their natural resources as a filial duty and honor.

Western Contact

Cook’s Ill-Fated Voyage

In the dawn hours of January 18, 1778, Captain James Cook of the HMS Resolution spotted an unfamiliar set of islands, which he later named for his benefactor, the Earl of Sandwich. The 50-year-old sea captain was already famous in Britain for “discovering” much of the South Pacific. Now on his third great voyage of exploration, Cook had set sail from Tahiti northward across uncharted waters. He was searching for the mythical Northwest Passage that was said to link the Pacific and Atlantic oceans. On his way, he stumbled upon Hawaii (aka the Sandwich Isles) quite by chance.

With the arrival of the Resolution, Stone Age Hawaii entered the age of iron. Sailors swapped nails and munitions for fresh water, pigs, and the affections of Hawaiian women. Tragically, the foreigners brought with them a terrible cargo: syphilis, measles, and other diseases that decimated the Hawaiian people. Captain Cook estimated the native population at 400,000 in 1778. (Later historians claim it could have been as high as 900,000.) By the time Christian missionaries arrived 40 years later, the number of Native Hawaiians had plummeted to just 150,000.

In a skirmish over a stolen boat, Cook was killed by a blow to the head. His British countrymen sailed home, leaving Hawaii forever altered. The islands were now on the sea charts, and traders on the fur route between Canada and China stopped here to get fresh water. More trade—and more disastrous liaisons—ensued.

Two more sea captains left indelible marks on the Islands. The first was American John Kendrick, who in 1791 filled his ship with fragrant Hawaiian sandalwood and sailed to China. By 1825, Hawaii’s sandalwood groves were gone. The second was Englishman George Vancouver, who in 1793 left behind cows and sheep, which ventured out to graze in the islands’ native forest and hastened the spread of invasive species. King Kamehameha I sent for cowboys from Mexico and Spain to round up the wild livestock, thus beginning the islands’ paniolo (cowboy) tradition.

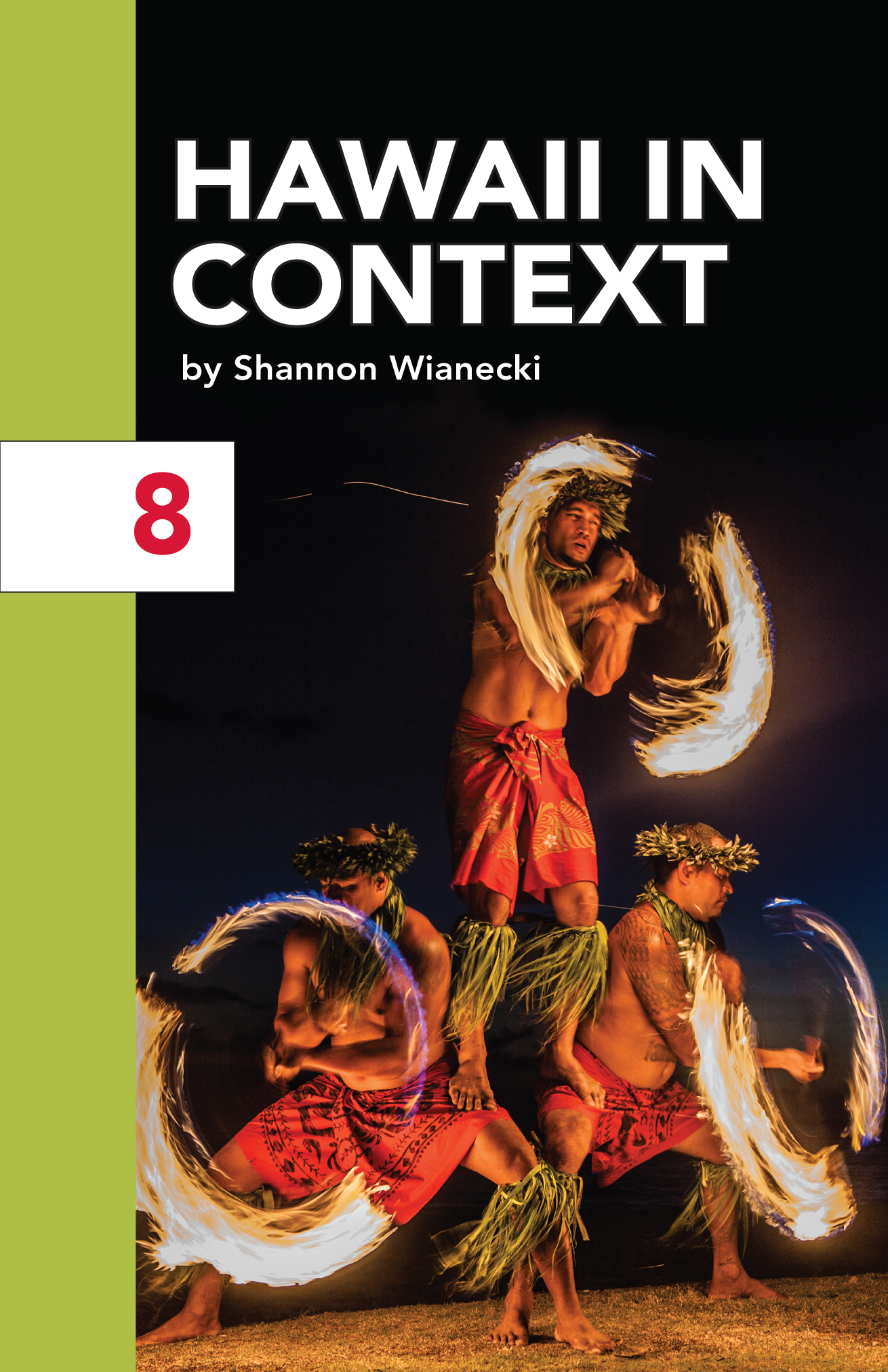

King Kamehameha I was an ambitious alii who used western guns to unite the islands under single rule. After his death in 1819, the tightly woven Hawaiian society began to unravel. One of his successors, Queen Kaahumanu, abolished the kapu system, opening the door for religion of another form.

King Kamehameha I.

King David Kalakaua.

Staying to Do Well

In April 1820, missionaries bent on converting Hawaiians arrived from New England. The newcomers clothed the natives, banned them from dancing the hula, and nearly dismantled the ancient culture. The churchgoers tried to keep sailors and whalers out of the bawdy houses, where whiskey flowed and the virtue of native women was never safe. To their credit, the missionaries created a 12-letter alphabet for the Hawaiian language, taught reading and writing, started a printing press, and began recording the islands’ history, which until that time had been preserved solely in memorized chants.

Children of the missionaries became business leaders and politicians. They married Hawaiians and stayed on in the islands, causing one wag to remark that the missionaries “came to do good and stayed to do well.” In 1848, King Kamehameha III enacted the Great Mahele (division). Intended to guarantee Native Hawaiians rights to their land, it ultimately enabled foreigners to take ownership of vast tracts of land. Within two generations, more than 80% of all private land was in haole (foreign) hands. Businessmen planted acre after acre in sugarcane and imported waves of immigrants to work the fields: Chinese starting in 1852, Japanese in 1885, and Portuguese in 1878.

Is Everyone hawaiian in Hawaii?

Only kanaka maoli (Native Hawaiians) are truly Hawaiian. The sugar and pineapple plantations brought so many different people to Hawaii that the state is now a remarkable potpourri of ethnic groups: Native Hawaiians were joined by Caucasians, Japanese, Chinese, Filipinos, Koreans, Portuguese, Puerto Ricans, Samoans, Tongans, Tahitians, and other Asian and Pacific Islanders. Add to that a sprinkling of Vietnamese, Canadians, African Americans, American Indians, South Americans, and Europeans of every stripe. Many people retain an element of the traditions of their homeland. Some Japanese Americans in Hawaii, generations removed from the homeland, are more traditional than the Japanese of Tokyo. The same is true of many Chinese, Koreans, and Filipinos, making Hawaii a kind of living museum of Asian and Pacific cultures.

King David Kalakaua was elected to the throne in 1874. This popular “Merrie Monarch” built Iolani Palace in 1882, threw extravagant parties, and lifted the prohibitions on the hula and other native arts. For this, he was much loved. He proclaimed that “hula is the language of the heart and, therefore, the heartbeat of the Hawaiian people.” He also gave Pearl Harbor to the United States; it became the westernmost bastion of the U.S. Navy. While visiting chilly San Francisco in 1891, King Kalakaua caught a cold and died in the royal suite of the Sheraton Palace. His sister, Queen Liliuokalani, assumed the throne.

The Overthrow

For years, a group of American sugar plantation owners and missionary descendants had been machinating against the monarchy. On January 17, 1893, with the support of the U.S. minister to Hawaii and the Marines, the conspirators imprisoned Queen Liliuokalani in her own palace. To avoid bloodshed, she abdicated the throne, trusting that the United States government would right the wrong. As the Queen waited in vain, she penned the sorrowful lyric “Aloha Oe,” Hawaii’s song of farewell.

U.S. President Grover Cleveland’s attempt to restore the monarchy was thwarted by congress. Sanford Dole, a powerful sugar plantation owner, appointed himself president of the newly declared Republic of Hawaii. His fellow sugarcane planters, known as the Big Five, controlled banking, shipping, hardware, and every other facet of economic life on the islands. In 1898, through annexation, Hawaii became an American territory ruled by Dole.

Oahu’s central Ewa Plain soon filled with row crops. The Dole family planted pineapple on its sprawling acreage. Planters imported more contract laborers from Puerto Rico (1900), Korea (1903), and the Philippines (1907–31). Many of the new immigrants stayed on to establish families and become a part of the islands. Meanwhile, Native Hawaiians became a landless minority. Their language was banned in schools and their cultural practices devalued, forced into hiding.

For nearly a century in Hawaii, sugar was king, generously subsidized by the U.S. government. Sugar is a thirsty crop, and plantation owners oversaw the construction of flumes and aqueducts that channeled mountain streams down to parched plains, where waving fields of cane soon grew. The waters that once fed taro patches dried up. The sugar planters dominated the territory’s economy, shaped its social fabric, and kept the islands in a colonial plantation era with bosses and field hands. But the workers eventually went on strike for higher wages and improved working conditions, and the planters found themselves unable to compete with cheap third-world labor costs.

Tourism Takes Hold

Tourism in Hawaii began in the 1860s. Kilauea volcano was one of the world’s prime attractions for adventure travelers. In 1865, a grass Volcano House was built on the rim of Halemaumau Crater to shelter visitors; it was Hawaii’s first hotel. The visitor industry blossomed as the plantation era peaked and waned.

In 1901, W. C. Peacock built the elegant Beaux Arts Moana Hotel on Waikiki Beach, and W. C. Weedon convinced Honolulu businessmen to bankroll his plan to advertise Hawaii in San Francisco. Armed with a stereopticon and tinted photos of Waikiki, Weedon sailed off in 1902 for 6 months of lecture tours to introduce “those remarkable people and the beautiful lands of Hawaii.” He drew packed houses. A tourism promotion bureau was formed in 1903, and about 2,000 visitors came to Hawaii that year.

The original Volcano House, Hawaii's first hotel.

Most everyone in Hawaii speaks English. But many folks now also speak olelo Hawaii, the native language of these Islands. You will regularly hear aloha and mahalo (thank you). If you’ve just arrived, you’re a malihini. Someone who’s been here a long time is a kamaaina. When you finish a job or your meal, you are pau (finished). On Friday, it’s pau hana, work finished. You eat pupu (Hawaii’s version of hors d’oeuvres) when you go pau hana.

The Hawaiian alphabet, created by the New England missionaries, has only 12 letters: the five regular vowels (a, e, i, o, and u) and seven consonants (h, k, l, m, n, p, and w). The vowels are pronounced in the Roman fashion: that is, ah, ay, ee, oh, and oo (as in “too”)—not ay, ee, eye, oh, and you, as in English. For example, huhu is pronounced who-who. Most vowels are sounded separately, though some are pronounced together, as in Kalakaua: “kah-lah-cow-ah.”

The steamship was Hawaii’s tourism lifeline. It took 4½ days to sail from San Francisco to Honolulu. Streamers, leis, and pomp welcomed each Matson liner at downtown’s Aloha Tower. Well-heeled visitors brought trunks, servants, and Rolls-Royces and stayed for months. Hawaiians amused visitors with personal tours, floral parades, and hula shows.

Beginning in 1935 and running for the next 40 years, Webley Edwards’s weekly live radio show, “Hawaii Calls,” planted the sounds of Waikiki—surf, sliding steel guitar, sweet Hawaiian harmonies, drumbeats—in the hearts of millions of listeners in the United States, Australia, and Canada.

By 1936, visitors could fly to Honolulu from San Francisco on the Hawaii Clipper, a seven-passenger Pan American Martin M-130 flying boat, for $360 one-way. The flight took 21 hours, 33 minutes. Modern tourism was born, with five flying boats providing daily service. The 1941 visitor count was a brisk 31,846 through December 6.

World War II & Statehood

On December 7, 1941, Japanese Zeros came out of the rising sun to bomb American warships based at Pearl Harbor. This was the “day of infamy” that plunged the United States into World War II.

The attack brought immediate changes to the Islands. Martial law was declared, stripping the Big Five cartel of its absolute power in a single day. German and Japanese Americans were interned. Hawaii was “blacked out” at night, Waikiki Beach was strung with barbed wire, and Aloha Tower was painted in camouflage. Only young men bound for the Pacific came to Hawaii during the war years. Many came back to graves in a cemetery called Punchbowl.

The postwar years saw the beginnings of Hawaii’s faux culture. The authentic traditions had long been suppressed, and into the void flowed a consumable brand of aloha. Harry Yee invented the Blue Hawaii cocktail and dropped in a tiny Japanese parasol. Vic Bergeron created the mai tai, a drink made of rum and fresh lime juice, and opened Trader Vic’s, America’s first themed restaurant that featured the art, decor, and food of Polynesia. Arthur Godfrey picked up a ukulele and began singing hapa-haole tunes on early TV shows. In 1955, Henry J. Kaiser built the Hilton Hawaiian Village, and the 11-story high-rise Princess Kaiulani Hotel opened on a site where the real princess once played. Hawaii greeted 109,000 visitors that year.

In 1959, Hawaii became the 50th state of the United States. That year also saw the arrival of the first jet airliners, which brought 250,000 tourists to the state. By the 1980s, Hawaii’s visitor count surpassed 6 million. Fantasy megaresorts bloomed on the neighbor islands like giant artificial flowers, swelling the luxury market with ever-swanker accommodations. Hawaii’s tourist industry—the bastion of the state’s economy—has survived worldwide recessions, airline industry hiccups, and increased competition from overseas. Year after year, the Hawaiian Islands continue to be ranked among the top visitor destinations in the world.

Hawaii Today

A Cultural Renaissance

Despite the ever-increasing influx of foreign people and customs, the Native Hawaiian culture is experiencing a rebirth. It began in earnest in 1976, when members of the Polynesian Voyaging Society launched Hokulea, a double-hulled canoe of the sort that hadn’t been seen on these shores in centuries. The Hokulea’s daring crew sailed her 2,500 miles to Tahiti without using modern instruments, relying instead on ancient navigational techniques. Most historians at that time discounted Polynesian wayfinding methods as rudimentary; the prevailing theory was that Pacific Islanders had discovered Hawaii by accident, not intention. The Hokulea’s successful voyage sparked a fire in the hearts of indigenous islanders across the Pacific, who reclaimed their identity as a sophisticated, powerful people with unique wisdom to offer the world.

Hula girls.

The Hawaiian language found new life, too. In 1984, a group of educators and parents recognized that, with fewer than 50 children fluent in Hawaiian, the language was dangerously close to extinction. They started a preschool where keiki (children) learned lessons purely in Hawaiian. They overcame numerous bureaucratic obstacles (including a law still on the books forbidding instruction in Hawaiian) to establish Hawaiian-language-immersion programs across the state that run from preschool through post-graduate education.

Hula—which never fully disappeared despite the missionaries’ best efforts—is thriving. At the annual Merrie Monarch festival commemorating King Kalakaua, hula halau (troupes) from Hawaii and beyond gather to demonstrate their skill and artistry. Fans of the ancient dance form are glued to the live broadcast of what is known as the Olympics of hula. Kumu hula (hula teachers) have safeguarded many Hawaiian cultural practices as part of their art: the making of kapa, the collection and cultivation of native herbs, and the observation of kuleana, an individual’s responsibility to the community.

In that same spirit, in May 2014, the traditional voyaging canoe Hokulea embarked on her most ambitious adventure yet: an international peace delegation. During the canoe’s 3-year circumnavigation of the globe, the crew’s mission is “to weave a lei around the world” and chart a new course toward a healthier and more sustainable horizon for all of humankind. The sailors hope to collaborate with political leaders, scientists, educators, and schoolchildren in each of the ports they visit.

The history of Hawaii has come full circle: the ancient Polynesians traveled the seas to discover these Islands. Today, their descendants set sail to share Hawaii with the world.

Dining in Hawaii

In the early days of Hawaii’s tourism industry, the food wasn’t anything to write home about. Continental cuisine ruled fine-dining kitchens. Meats and produce arrived much the same way visitors did: jet-lagged after a long journey from a far-off land. Island chefs struggled to revive limp iceberg lettuce and frozen cocktail shrimp—often letting outstanding ocean views make up for uninspired dishes. In 1991, 12 chefs staged a revolt. They partnered with local farmers, ditched the dictatorship of imported foods, and brought sun-ripened mango, crisp organic greens, and freshly caught uku (snapper) to the table. Coining the name “Hawaii Regional Cuisine,” they gave the world a taste of what happens when passionate, classically trained cooks have their way with ripe Pacific flavors.

Ahi poke.

Two decades later, the movement to unite local farms and kitchens is still bearing fruit. The HRC heavyweights continue to keep things hot in island kitchens. But they aren’t, by any means, the sole source of good eats in Hawaii.

Haute cuisine is alive and well in Hawaii, but equally important in the culinary pageant are good-value plate lunches, shave ice, and food trucks.

The plate lunch, which is ubiquitous throughout the islands, can be ordered from a lunch wagon or a restaurant and usually consists of some protein—fried mahimahi, say, or teriyaki beef, shoyu chicken, or chicken or pork cutlets served katsu style: breaded and fried and slathered in a rich gravy—“two scoops rice,” macaroni salad, and a few leaves of green, typically julienned cabbage. Chili water and soy sauce are the condiments of choice. Like saimin—the local version of noodles in broth topped with scrambled eggs, green onions, and sometimes pork—the plate lunch is Hawaii’s version of comfort food.

Shave ice.

Because this is Hawaii, at least a few fingerfuls of poi—steamed, pounded taro (the traditional Hawaiian staple crop)—are a must. Mix it with salty kalua pork (pork cooked in a Polynesian underground oven known as an imu) or lomi salmon (salted salmon with tomatoes and green onions). Other tasty Hawaiian foods include poke (pronounced “po-kay,” this popular appetizer is made of cubed raw fish seasoned with onions, seaweed, and roasted kukui nuts), laulau (pork, chicken, or fish steamed in ti leaves), squid luau (cooked in coconut milk and taro tops), haupia (creamy coconut pudding), and kulolo (a steamed pudding of coconut, brown sugar, and taro).

For a sweet snack, the prevailing choice is shave ice. Particularly on hot, humid days, long lines of shave-ice lovers gather for heaps of finely shaved ice topped with sweet tropical syrups. Sweet-sour li hing mui is a favorite, and new gourmet flavors include calamansi lime and red velvet cupcake. Aficionados order shave ice with ice cream and sweetened adzuki beans on the bottom or sweetened condensed milk on top.

When to Go

Most visitors come to Hawaii when the weather is lousy most everywhere else. Thus, the high season—when prices are up and resorts are often booked to capacity—is generally from mid-December to March or mid-April. The last 2 weeks of December, in particular, are prime time for travel to Hawaii. Spring break is also jam-packed with families taking advantage of the school holiday. If you’re planning a trip during peak season, make your hotel and rental car reservations as early as possible, expect crowds, and prepare to pay top dollar.

The off season, when the best rates are available and the islands are less crowded, is late spring (mid-Apr to early June) and fall (Sept to mid-Dec).

If you plan to travel in summer (June–Aug), don’t expect to see the fantastic bargains of spring and fall—this is prime time for family travel. But you’ll still find much better deals on packages, airfare, and accommodations in summer than in the winter months.

Climate

Because Hawaii lies at the edge of the tropical zone, it technically has only two seasons, both of them warm. There’s a dry season that corresponds to summer (Apr–Oct) and a rainy season in winter (Nov–Mar). It rains every day somewhere in the islands at any time of the year, but the rainy season can bring enough gray weather to spoil your tanning opportunities. Fortunately, it seldom rains in one spot for more than 3 days straight.

The year-round temperature doesn’t vary much. At the beach, the average daytime high in summer is 85°F (29°C), while the average daytime high in winter is 78°F (26°C); nighttime lows are usually about 10° cooler. But how warm it is on any given day really depends on where you are on the island.

Each island has a leeward side (the side sheltered from the wind) and a windward side (the side that gets the wind’s full force). The leeward sides (the west and south) are usually hot and dry, while the windward sides (east and north) are generally cooler and moist. When you want arid, sunbaked, desert-like weather, go leeward. When you want lush, wet, jungle-like weather, go windward.

Hawaii also has a wide range of microclimates, thanks to interior valleys, coastal plains, and mountain peaks. On the Big Island, Hilo ranks among the wettest cities in the nation, with 180 inches of rainfall a year. At Puako, only 60 miles away, it rains less than 6 inches a year. The summits of Mauna Kea on the Big Island and Haleakala on Maui often see snow in winter—even when the sun is blazing down at the beach. The locals say if you don’t like the weather, just drive a few miles down the road—it’s sure to be different!

Holidays

When Hawaii observes holidays (especially those over a long weekend), travel between the islands increases, interisland airline seats are fully booked, rental cars are at a premium, and hotels and restaurants are busier.

Federal, state, and county government offices are closed on all federal holidays. Federal holidays in 2016 include New Year’s Day (Jan 1); Martin Luther King, Jr., Day (Jan 18); Washington’s birthday (Feb 16); Memorial Day (May 30); Independence Day (July 4); Labor Day (Sept 5); Columbus Day (Oct 12); Veterans Day (Nov 11); Thanksgiving Day (Nov 24); and Christmas (Dec 25).

Hey, No Smoking in Hawaii |

Well, not totally no smoking, but Hawaii has one of the toughest laws against smoking in the U.S. The Hawaii Smoke-Free Law prohibits smoking in public buildings, including airports, shopping malls, grocery stores, retail shops, buses, movie theaters, banks, convention facilities, and all government buildings and facilities. There is no smoking in restaurants, bars, and nightclubs. Most bed-and-breakfasts prohibit smoking indoors, and more and more hotels and resorts are becoming smoke-free even in public areas. Also, there is no smoking within 20 feet of a doorway, window, or ventilation intake (so no hanging around outside a bar to smoke—you must go 20 ft. away). Even some beaches have no-smoking policies.

State and county offices are also closed on local holidays, including Prince Kuhio Day (Mar 25), honoring the birthday of Hawaii’s first delegate to the U.S. Congress; King Kamehameha Day (June 11), a statewide holiday commemorating Kamehameha the Great, who united the islands and ruled from 1795 to 1819; and Admission Day (third Fri in Aug), which honors the admittance of Hawaii as the 50th state on August 21, 1959.

Hawaii Calendar of Events

Please note that, as with any schedule of upcoming events, the following information is subject to change; always confirm the details before you plan your trip around an event.

January

Waimea Ocean Film Festival, Waimea and the Kohala Coast, Big Island. Several days of films featuring the ocean, ranging from surfing and Hawaiian canoe paddling to ecological issues. Go to http://waimeaoceanfilm.org or call 808/854-6095. First weekend after New Year’s Day.

February

Chinese New Year, most islands. In 2015, lion dancers will be snaking their way around the state on February 19, the start of the Chinese Year of the Sheep. Visit www.chinesechamber.com or call 808/533-3181. On Maui, lion dancers perform at the historic Wo Hing Temple on Front Street (www.visitlahaina.com). Call 888/310-1117 or 808/667-9175. Also in Wailuku; call 808/244-3888 for location.

March

Kona Brewers Festival, King Kamehameha’s Kona Beach Hotel Luau Grounds, Kailua-Kona, Big Island. This 5-day annual event features microbreweries from around the world, with beer tastings, food, and entertainment. Go to http://konabrewersfestival.com or call 808/987-9196. Mid-March.

Prince Kuhio Day Celebrations, all islands. On this state holiday, various festivals throughout Hawaii celebrate the birth of Jonah Kuhio Kalanianaole, who was born on March 26, 1871, and elected to Congress in 1902.

April

Merrie Monarch Hula Festival, Hilo, Big Island. Hawaii’s biggest, most prestigious hula festival features a week of modern (auana) and ancient (kahiko) dance competition in honor of King David Kalakaua, the “Merrie Monarch” who revived the dance. Tickets sell out by January, so reserve early. Go to www.merriemonarch.com or call 808/935-9168. March 27-April 2, 2016.

May

Outrigger Canoe Season, all islands. From May to September, canoe paddlers across the state participate in outrigger canoe races nearly every weekend. Go to www.ocpaddler.com for this year’s schedule of events.

Big Island Chocolate Festival, Kona, Big Island. This celebration of chocolate (cacao) grown and produced in Hawaii features symposiums, candy-making workshops, and gala tasting events. It’s held in the Fairmont Orchid hotel. Go to www.bigislandchocolatefestival.com or call 808/854-6769. First or second weekend in May.

June

Obon Season, all islands. This colorful Buddhist ceremony honoring the souls of the dead kicks off in June. Synchronized dancers circle a tower where Taiko drummers play, and food booths sell Japanese treats late into the night. Each weekend, a different Buddhist temple hosts the Bon Dance. Go to www.gohawaii.com for a statewide schedule.

August

Puukohola Heiau National Historic Site Anniversary Celebration, Kawaihae, Big Island. This homage to authentic Hawaiian culture begins at 6am at Puukohola Heiau. It’s a rugged, beautiful site where attendees make leis, weave lauhala mats, pound poi, and dance ancient hula. Bring refreshments and sunscreen. Go to http://www.nps.gov/puhe.htm or call 808/882-7218. Mid-August.

Admission Day, all islands. Hawaii became the 50th state on August 21, 1959. On the third Friday in August, the state takes a holiday (all state-related facilities are closed).

September

Queen Liliuokalani Canoe Race, Kailua-Kona to Honaunau, Big Island. Thousands of paddlers compete in the world’s largest long-distance canoe race. Go to www.kaiopua.org or call 808/938-8577. Labor Day weekend.

Parker Ranch Round-Up Rodeo, Waimea, Big Island. This hot rodeo competition is in the heart of cowboy country. Go to http://parkerranch.com/labor-day-weekend-rodeo/ or call 808/885-7311. Weekend before Labor Day.

Aloha Festivals, various locations on all islands. Parades and other events celebrate Hawaiian culture and friendliness throughout the state. Go to www.alohafestivals.com or call 808/ 923-2030.

October

Ironman Triathlon World Championship, Kailua-Kona, Big Island. Some 1,500-plus world-class athletes run a full marathon, swim 2.5 miles, and bike 112 miles on the Kona-Kohala Coast of the Big Island. Spectators watch the action along the route for free. The best place to see the 7am start is along the Alii Drive seawall, facing Kailua Bay; arrive before 5:30am to get a seat. (Alii Dr. closes to traffic; park on a side street and walk down.) To watch finishers come in, line up along Alii Drive from Holualoa Street to Palani Road. The first finisher can arrive as early as 2:30pm. Go to www.ironmanworldchampionship.com or call 808/329-0063. Saturday closest to the full moon in October.

November

Kona Coffee Cultural Festival, Kailua-Kona, Big Island. Celebrate the coffee harvest with a bean-picking contest, lei contests, song and dance, and the Miss Kona Coffee Pageant. Go to http://konacoffeefest.com or call 808/326-7820. Events throughout November.

Hawaii International Film Festival, various locations throughout the state. This cinema festival with a cross-cultural spin features filmmakers from Asia, the Pacific Islands, and the United States. Go to www.hiff.org or call 808/792-1577. Mid-October to early November.

Invitational Wreath Exhibit, Volcano Art Center, Hawaii Volcanoes National Park, Big Island. Thirty-plus artists, including painters, sculptors, glass artists, fiber artists, and potters, produce both whimsical and traditional “wreaths” for this exhibit. Park entrance fees apply. Go to www.volcanoartcenter.org or call 808/967-7565. Mid-November to early January.

December

Kona Surf Film Festival, Courtyard Marriott King Kamehameha’s Kona Beach Hotel, Big Island. An outdoor screening of independent films focusing on waves and wave riders. Go to www.konasurffilmfestival.org or call 808/936-0089. Early December.