For decades this Golden Guide has introduced millions of people to the birds of North America. During that time bird watching (or “birding” as it is now commonly known) has grown dramatically. So too has our knowledge of birds and the sophistication of birders. This Revised Edition is a response to those changes. It contains additional birds, reworked descriptions, and range maps based on the latest data. The text has been extensively rewritten throughout to incorporate new information and to update the common and scientific names for birds (nomenclature) and their classification (taxonomy).

Although this guide is thoroughly updated, we have sought to preserve the strengths of the previous editions. We have resisted the temptation to add more pages. Too many guides have become too heavy and too unwieldy to be used conveniently in the field. We have retained the guide’s direct style, easy-to-use design, and informative and beautiful artwork. The combination of authoritative information, broad coverage, portable size, and convenient design make Birds of North America the easiest guide to use in the field.

Species Covered This guide will help you identify all of the species of birds that nest in North America north of Mexico. It also includes vagrants that occur regularly and nearly all the accidentals that arrive from other continents. Special emphasis is given to the different plumages of each species, to characteristic behaviors that will enable you to identify birds at a distance, and to typical song patterns. Because most North American species are migratory, observers anywhere on this continent have an opportunity to find a great variety of species close to home. The unique maps in this guide not only show breeding and winter ranges, but spring arrival dates as well.

Special Features This edition retains the convenient placement of the text, art, Sonagram, and map for each species on facing pages. This allows you to find all the information about a single species in one place. The full-color illustrations show birds in typical habitats, instead of isolating them on a page. Useful comparison plates help distinguish closely related species at a glance.

Most of the birds included in this guide have been identified in North America at least five times within the last 100 years and can be expected to occur again. These birds fall into several different categories, including:

Breeding Birds are species of native and introduced birds that nest regularly north of Mexico. All are included in this guide.

American Robin

Regular Visitors, such as seabirds from the southern hemisphere and land birds from eastern Asia, Mexico, and the West Indies, migrate or wander regularly to North America.

Wilson’s Storm–Petrel

Casual and Accidental Visitors are foreign species that stray occasionally into our region, especially in western Alaska, extreme southern United States, Newfoundland, or Greenland. Those considered most likely to occur again are included.

Bridled Tern

The category each bird falls into is indicated in its description (see Abundance). Extinct species and introduced and escaped birds that are not widely established are not included.

Names of Birds In this book each species is designated by both its common name and its scientific name.

Common Names Some birds have many different local names. For example, the Northern Bobwhite is called partridge in many parts of the South, but in much of the North the bird known as a partridge is a Ruffed Grouse. To avoid confusion, the English Names used in this guide follow those adopted by the American Ornithologists’ Union in the latest edition of The A.O.U. Check-List of North American Birds.

Scientific Names Each species of bird is assigned a Latin or scientific name, which is understood and accepted throughout the world. These Latin names often indicate relationships between species better than common names. Changes in classification are made as new light is shed on the relationships among species. The scientific names used in this guide are also adopted from The A.O.U. Check-List.

A scientific name consists of two parts—the genus name, which is capitalized, followed by the species name, as in Poecile carolinesis (Carolina Chickadee). Closely related species belong to the same genus. Closely related genera (the plural of genus) belong to the same family. And closely related families belong to the same order. All birds belong to the class Aves.

Taxonomy Because they reveal relationships, scientific names are the very foundation of the classification, or taxonomy, of birds. Scientists

GEOGRAPHIC SCOPE This guide covers all of North America north of Mexico, a continental land mass of over 9 million square miles. North America has a rich variety of subtropical, temperate, and arctic environments. The map above shows the major natural vegetative regions, which depend on latitude, altitude, rainfall, and other factors. The distribution of birds tends to fit into these large natural regions, and even more closely into the specific habitats they contain.

examine all attributes of each bird, including its DNA, to determine how it is related to other birds. This has led to some groupings that may seem unusual, but are still correct scientifically. For example, New World vultures have recently been removed from the order Falconiformes (hawks and other birds of prey) and reassigned to Ciconiiformes, because of their closer relationship to storks. In general, the taxonomic sequence follows a “natural” or evolutionary order, progressing from the least to the more advanced. However, because this book is intended to be used to aid identification in the field, it contains some exceptions to taxonomy. Vultures, for example, remain adjacent to hawks because they can be confused in the field.

Map based on Life Areas of N.A., by John W. Aldrich, Journal of Wildlife Management.

USING THIS BOOK

USING THIS BOOK

Overall, this guide follows the currently accepted taxonomic sequence for orders and families of birds. But, because it is intended to be used in the field, this guide sometimes departs from the sequence to make it easier to compare birds that look similar, but are not closely related. For example, herons and flamingos appear with the similarly shaped cranes, even though they are in different orders.

Families and Groups Similar birds are grouped by characteristics such as size, shape, posture, habits, and the length and shape of bills and tails. Brief introductory paragraphs summarize the common characteristics of each order and family (and some other groups).

Silhouettes To help you identify birds more quickly, silhouettes of birds with similar shapes are found at the beginning of most family sections (and some other large groups). The group illustrated in that section are shown in black. Silhouettes of birds that might be confused with that group are blue.

Illustrations The plates show an adult male, usually in breeding plumage. A female is also shown when her plumage is different. The male is indicated by  , the female by

, the female by  . Immatures (im.) are also illustrated when noticeably different from adults (ad.). Juvenile (juv.) plumage is shown for some species. If birds have very different summer and winter plumages, these are also shown. The color morphs (also called phases) of a few species are given and comparison illustrations call attention to similar species that are found on separate pages. Most birds typically seen in flight are illustrated in the flying position.

. Immatures (im.) are also illustrated when noticeably different from adults (ad.). Juvenile (juv.) plumage is shown for some species. If birds have very different summer and winter plumages, these are also shown. The color morphs (also called phases) of a few species are given and comparison illustrations call attention to similar species that are found on separate pages. Most birds typically seen in flight are illustrated in the flying position.

Comparison Plates Even experienced birders are sometimes perplexed by birds that look very similar. To help deal with this problem, this guide provides a number of plates featuring closely related birds that are difficult to tell apart. Those groups are:

| Female Ducks in Flight | Immature Gulls | Fall Warblers | |

| Hawks in Flight | Immature Terns | Sparrows | |

| Small Shorebirds | Spring Warblers |

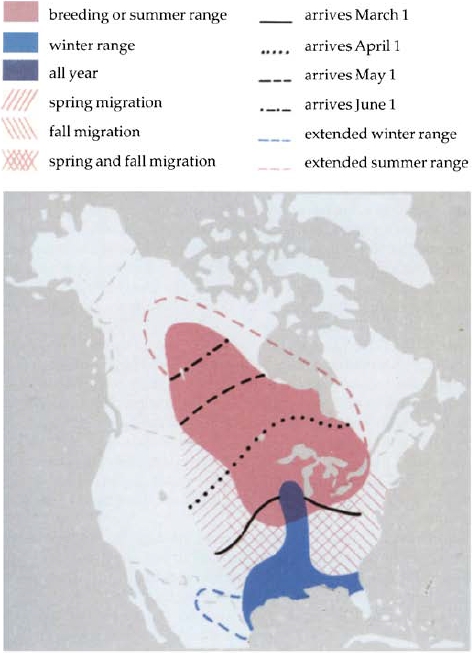

RANGE MAPS Except for species with restricted ranges, the range maps in this guide use North America as a base. The breeding or summer range is red, winter range blue. Areas where the species occurs all year are purple. Areas where birds pass only during migration are shown by red hatching slanting up from left to right for spring, down for fall, or cross-hatching for both. Black lines show average first arrival dates in spring; dashed blue or red lines bound areas where some species occasionally extend their range during winter or summer.

Range Maps Once you have found the proper family for a bird you are trying to identify, a quick glance at the maps can help rule out species unlikely to be found in your area. A fuller explanation of the range maps is found here.

Abundance Throughout this guide, several terms are used to describe the abundance of a species within its principal geographic range.

An abundant bird is one very likely to be seen in large numbers every time a person visits its habitat at the proper season.

A common bird may be seen most of the time or in smaller numbers.

An uncommon bird may be seen quite regularly in small numbers in the appropriate environment and season.

A rare bird occupies only a small percentage of its preferred habitat or occupies a very specific limited habitat. It is usually found only by an experienced birder.

When modified by the word local, the terms above indicate relative abundance in a very restricted area. It is also important to remember that the abundance of a species decreases rapidly near the edge of its range.

Habitat The text indicates the habitats generally preferred during the nesting season. Some preferences for winter habitat also are given if they are different from those in the breeding season. During migration, most species may be found in a much broader range of habitats. Even so, birds typical of wetland habitats in nesting season show a strong preference for wetlands in other seasons, and birds of open country usually prefer open habitats.

Abbreviations A number of abbreviations have been used to save space and convey information quickly. Besides common abbreviations for months, states, and provinces, you will find: feet:’, inches:″, length: L, wingspan: W, adult: ad., immature: im., juvenile: juv., and number of songs given per minute: x/min. A  indicates the male, a

indicates the male, a  the female.

the female.

Measurements The measurements given in this guide are based on actual field measurements of thousands of live birds in natural positions. They indicate the total length from the tip of the bill to the tip of the tail. These live measurements are shorter than conventional ones (of dead birds, stretched “with reasonable force”), but reflect the size of a living bird when it is actually seen. The single figure given for length (L) is an average figure for an adult male, rounded to the nearest ¼ inch in small birds and to the nearest ½ inch or 1 inch in larger birds. Individual birds may be longer or shorter. Thus a bird recorded a L 10″ will be between 9 and 11 inches long. If the genders differ appreciably in size, this is usually mentioned. For larger flying or soaring birds, an average wingspan (W) measurement is also given, in inches.

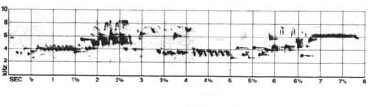

BIRD SONGS The songs of many species are described in this guide, often indicating the normal number of repetitions given per minute (x/min.). Numerous songs or calls are also represented by Sonagrams.

American Robin

Many birders learn to identify numerous birds by song alone, but it is difficult to describe bird songs adequately with words—nor can bird songs be shown accurately on a musical staff. Dr. Peter Paul Kellogg of the Laboratory of Ornithology, Cornell University, developed methods for recording bird songs in the field and reproducing them visually as Sonagrams. Sonagrams contain much more information than a few descriptive words can convey. With a little practice you can use them to visualize the approximate pitch of an unfamiliar bird song (in relation to species you know), its quality (clear, harsh, buzzy, mechanical), phrasing (separate notes, repetitions, trills, continuous song, or phrases), and tempo (even, accelerating, or slowing). You can also judge the length of individual notes and of the entire song, and recognize changes in loudness.

The Sonagrams reproduced in this guide have been carefully selected to represent typical individuals of each species. Most show 2½ seconds of song. Pitch, usually up to six kilocycles per second (kilo-hertz), is marked in the left margin at two kHz intervals. For pitch comparison, middle C of the piano and the four octaves above middle C are indicated in the right margin of the enlarged robin Sonagram above. Middle C has a frequency of 0.262 kHz. The frequency doubles with each succeeding octave: C’ is 0.523, C″ is 1.046. C″ ′ is 2.093, and C″ ″ (top note on the piano) is 4.186 kHz.

Knowledge of music is not necessary for reading Sonagrams. Even a tone-deaf person can detect differences in pattern, timing, and quality. First, study Sonagrams of birds you know well. Then use Sonagrams to make comparisons and to remind yourself of the sound patterns of different species.

Three toots on an automobile horn are easy to read. The “wolf whistle” shows how a human whistle appears as a single narrow line that rises and falls as pitch changes. Compare it with the Eastern Meadowlark. Very high-pitched songs (6–12 kHz) are shown on an extra high Sonagram. A ticking clock has no recognizable pitch, but each tick appears in the Sonagram as a vertical line, indicating a wide frequency range. Compare the clock ticks with the Sedge Wren Sonagram.

Some birds, such as a thrasher, have very long songs. In such cases only a typical portion is shown. For some other birds with typical songs that exceed 2½ seconds (Purple Finch, House Wren), a shorter complete song is used. Study some common songs. The Northern Bobwhite’s consists of a faint introductory whistle, a short loud whistle, and a longer upward-slurred note that is not as pure as the preceding whistle. The Black-capped Chickadee’s “phoebe” song consists of 2 or 3 whistles you can easily imitate. The first note is a full tone higher than the next. Buzzy songs and calls (Grasshopper Sparrow, Common Nighthawk) and buzzy elements of complex songs cover a broad frequency range on their Sonagrams. Many songs have overtones or harmonics that give a richness of quality. These appear as generally fainter duplicates at octaves above the main or fundamental pitch. High-pitched harmonics are “drowned out” by the louder lower notes. Birds, like people, have individual and geographical differences in their voices; yet any typical song is distinctive enough to be recognized by an experienced observer.

Winter Wren

automobile horn

“wolf whistle”

Eastern Meadowlark

ticking clock

Sedge Wren

Purple Finch

Many excellent recordings of bird songs and calls are available, including:

Guide to Bird Sounds, Cornell Laboratory of Ornithology, National Geographic Society, 1985.

A Field Guide to Bird Songs of Eastern and Central North America, rev. ed., by Roger Tory Peterson, Houghton Mifflin, 1999.

Birding By Ear: Guide to Bird Song Identification, and More Birding By Ear: Eastern/Central, rev. ed., by Richard K. Walton and Robert W. Lawson, Houghton Mifflin, 1999.

Brewer’s Sparrow

There are very few places where you cannot enjoy bird watching. Birds can be found in city parks, sanctuaries, wood margins, open areas, and along shores. National Parks, Monuments, and Wildlife Refuges are excellent places to observe birds. Planting for shelter and providing food and water will attract many species, even to a small yard.

When you look for birds, walk slowly and quietly. Do not wear brightly colored clothing. If you are quiet and partly concealed, birds will often approach closer than if you are out in the open. Even your parked car can serve as a blind. You can attract songbirds and draw them close by repeatedly “pshshing” or “squeaking” (sucking air through your lips) or noisily kissing the back of your hand. Some species will respond to whistled imitations of their song.

As you gain experience in identifying birds, you will begin to recognize the distinctive characteristics of each species. These include a bird’s color and shape (known as field marks), and behaviors associated with a particular species or group of birds.

Field Marks When you want to identify a bird, focus first on its head. Many species can be identified by their head alone. Carefully examine the shape and color of the bill and its length relative to the head. Look for dark lines or light stripes or a ring around the eye. What color is the throat? Are there other distinctive markings on the head? How conspicuous are these markings?

Check routinely for wing bars, tail spots, streaking on breast or back, and rump patches. In flight, watch for patterns of color on the wings or head. Sometimes you will only see a flash of color, but it can be a decisive clue in making an identification.

Hybrids between closely related species sometimes occur in the wild. You should also watch for albinism, which occurs occasionally in most species of wild birds. Pure white or pale brown forms are rare. More frequently the normal plumage is modified by white feathers on the wings or tail or in patches on the body. A morph is a color variation within a species.

Behavior Look for distinctive actions such as tail wagging or flicking, or the bird’s manner of walking, hopping, feeding, or flying.

Habitat Where you see a bird will often help narrow your choices when trying to identify it. Many species tend to appear most often in a particular habitat. In this guide, habitats are often indicated in the illustrations and mentioned in the text. One quick way to focus on likely species is to compare the habitat shown with the location where you saw the bird.

Equipment Binoculars (7 to 10 power, with central focus) are almost essential. A spotting scope (20 to 30 power) can be useful, especially when looking at waterfowl or shorebirds. Camera fans will want a 35 mm camera with a telephoto lens or a video camera. A tripod can improve your images. A handy, portable guide like this one is also essential. Your identifications will be much more reliable if you can check them on the spot, rather than relying on your memory later.

After you learn to name birds on sight, you may also want to participate in a variety of amateur activities that contribute to scientific studies. These include organized bird counts, banding, atlasing, and intensive studies of individual species. You can find out about such activities by contacting a local bird club or the national organizations listed on the following page.

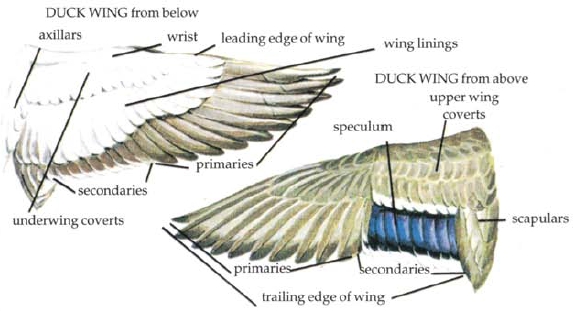

DESCRIBING BIRDS Using the correct terminology for the parts of a bird will help you describe an unknown bird or check on variations in color and pattern of local birds. The terms on this page are commonly used by birders. Knowing the terminology also helps focus your attention on specific parts of a bird as you observe it. Sometimes such details as an incomplete eye ring or the color of the undertail coverts can clinch an identification.

TOPOGRAPHY OF A BIRD

PARTS OF WING

Local Bird Clubs Audubon groups or ornithological societies are found in every state and Canadian province, especially in larger cities. The clubs hold meetings, lectures, and field trips. Many larger cities or universities have museums with bird collections, and study here can greatly aid field recognition. Many tours are run specifically for bird study.

American Birding Association, Box 4335, Austin, TX 78765; Birding.

American Ornithologists’ Union, National Museum of Natural History, Smithsonian Institution, Washington, D.C. 20560; Auk.

Cooper Ornithological Society, Department of Zoology, University of California, Los Angeles, CA 90052; Condor.

National Audubon Society, 950 Third Avenue, New York, NY 10022; Audubon and American Birds.

Wilson Ornithological Society, Museum of Zoology, University of Michigan, Ann Arbor, MI 48104; Wilson Bulletin.

WildBird, P.O. Box 57347, Boulder, CO 80323-7347, www.animalnetwork.com.

Bird Times, 7-L Dundas Circle, Greensboro, NC 27499-0765.

Bird Watcher’s Digest, P.O. Box 110, Marietta, OH 45750-9962.

Birder’s World, P.O. Box 1612, Waukesha, WI53187-9950.

The web is full of interesting information about birds and birding. Some good places to start are:

http://birdsource.cornell.edu/—Cornell Lab. Of Ornithology

http://www.birdwatching.com/index.html

http://www-stat.wharton.upenn.edu/~siler/birdlinks.html

http://www.pwrc.usgs.gov/—USGS Patuxent Wildlife Research Center

http://www.mbr.nbs.gov/id/songlist.html

Austin, Jr., Oliver L., and Arthur Singer, Families of Birds, Golden Press, New York, 1971.

Brooke, Michael and Tim Birkhead (eds.), The Cambridge Encyclopedia of Ornithology, Cambridge University Press, New York, 1991.

Coe, James, Eastern Birds, St. Martin’s Press, New York, rev. ed. 2001.

Connor, Jack, The Complete Birder: A Guide to Better Birding, Houghton Mifflin Company, Boston, 1988.

Dunn, Jon L. and Kimball L. Garrett, Warblers of North America, Peterson Field Guides, Houghton Mifflin Company, Boston, 1997.

Ehrlich, Paul R., David S. Dobkin, and Darryl Wheye, The Birder’s Handbook, Simon & Schuster, New York, 1988.

Kaufman, Kenn, Birds of North America, Houghton Mifflin Company, Boston, 2000.

———, Field Guide to Advanced Birding: Birding Challenges and How to Approach Them, Peterson Field Guides, Houghton Mifflin Company, Boston, 1999.

———, Lives of North American Birds, Houghton Mifflin Company, Boston, 1996.

Latimer, Jonathan P., and Karen Stray Nolting, Backyard Birds, Houghton Mifflin Company, Boston, 1999.

———, Birds of Prey, Houghton Mifflin Company, Boston 1999.

———, Bizarre Birds, Houghton Mifflin Company, Boston, 1999.

———, Shorebirds, Houghton Mifflin Company, Boston 1999.

———, Songbirds, Houghton Mifflin Company, Boston, 2000.

Monroe, Jr., Burt L. and Charles G. Sibley, A World Checklist of Birds, Yale University Press, New Haven, CT, 1993.

Peterson, Roger Tory, A Field Guide to the Birds: A Completely New Guide to All the Birds of Eastern and Central North America, rev. ed. Houghton Mifflin Company, Boston, 1998.

———, A Field Guide to Western Birds, rev. ed., Houghton Mifflin Company, Boston, 1990.

Proctor, Noble S., Roger Tory Peterson, and Patrick J. Lynch, A Manual of Ornithology: Avian Structure & Function, Yale University Press, New Haven, 1993.

Sibley, David Allen, The Sibley Guide to Birds, Alfred A. Knopf, New York, 2000.

Terres, John K., The Audubon Society Encyclopedia of North American Birds, Alfred A. Knopf, New York, 1980.

Welty, Joel Carl and Luis Baptista, The Life of Birds, 4th ed., Saunders, Philadelphia, 1988.