BUTT MOP

Rebecca downloaded the next batch of BATSE data the next afternoon while Tane had his turn steering the sub. A few boats had been cruising the area, and the fine weather of the previous day had disappeared, replaced by squally showers, so they had taken the precaution of submerging and continuing the trip in the relative calm of the ocean depths.

“More of the same,” Rebecca said, peering at the characters on the screen of her laptop. “Just more of the same.”

Since the “Water Works” and the as-yet-indecipherable “Butt Mop,” there had been nothing but numbers. Always a series of numbers, separated by commas, then a full stop, then another series. Not Lotto numbers; they didn’t fit the pattern. Something else. Something with a lot of numbers!

Every day it seemed there were more transmissions captured by the satellite and uploaded to the BATSE Web site. They had set both Tane’s computer and Rebecca’s shiny new laptop running Rebecca’s program, day and night, and were working through the backlog of transmissions that had been coming in ever since they had visited Dr. Barnes at the university.

Rebecca had tried every combination and calculation she could think of to make some sense out of the numbers, but the answer still eluded her. She was convinced, and had said so many times, that the solution would be something not logical. Something lateral. Something that Tane’s creative imagination would be needed to solve.

“Come on, Tane,” she said. “We need you to think outside the box.”

Tane stared out at the monotonous sameness of the ocean. It was hard to think creatively when you had a splitting headache, and he had one now. He hadn’t slept much the previous night but had lain awake worried about breaking into the lab. That was against the law. It was a criminal act. He had never broken the law before (unless you counted that packet of gum he had “borrowed” from the corner store when he was seven). He had rolled over and over in his tiny bunk, and now his head throbbed with the pulse of the engines. Think outside the box.

He wasn’t the only one feeling the stress of the mission. He could see it on the faces of the others, especially Rebecca. She could not afford to go to jail. Could any of them? No. But especially not Rebecca. Yet it had to be done. What were the consequences if they did it? What would be the consequences if they didn’t?

In the clear open water here, there was nothing much to look at. Just the occasional school of fish or curious shark. Ahead at Poor Knights Islands there was a world-famous diving spot, renowned for its clear waters, colorful marine life, and the wreck of the Rainbow Warrior. But that was a bit off course for them, so he had to be content with the blue-green infinity of the open water.

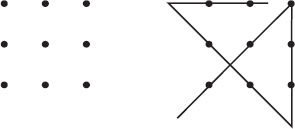

Think outside the box. It was a well-worn phrase from an old puzzle that he had once seen. Nine dots that formed a three-by-three grid. Join all the dots using just four lines. It seemed impossible to most logical people, but creative thinkers quickly realized that it was easy, if you allowed your four lines to extend beyond the confines of the grid. Outside the box.

He sketched the puzzle on a notepad, then completed the lines to make the answer.

Something struck him about that phrase. Think outside the box. He stopped trying to solve it and let his mind drift idly, like the ocean around them. The dead fish in the beer rings came to mind, but he shook that away quickly. Quick flashes of many things, superimposed on each other—Fatboy’s hand on Rebecca’s shoulder, the nervous lawyer absentmindedly pulling at his mustache, the fantail family naively fearless in their flimsy nest, the chessboard he had bought Rebecca for Christmas. And as it usually did, the answer just floated into his mind and was there for quite a while before he realized it.

The chessboard. Think outside the box. Black and white chess pieces, black and white boxes on the chessboard. Boxes. Think outside the box. The chessboard itself was a box, made up of smaller black and white boxes. Think inside the box!

“The chessboard,” he finally said out loud.

Rebecca was in the main cabin, sitting on one of the bunks, working on her computer. She looked through the pressure door at him. “What chessboard?”

“Any chessboard,” Tane said quickly.

Fatboy had been lying on one of the other bunks, but now he walked over and sat in the codriver’s seat. “Go on,” he said purposefully. He was wearing his cowboy hat, which seemed a little silly to Tane.

“A chessboard is made up of eight boxes by eight boxes, right? Some black, some white.”

“Yes.”

Rebecca was starting to get it, Tane thought.

“Suppose you had a chessboard that was made up of one thousand boxes by one thousand boxes. That would be one thousand squared.” He picked up the notepad and wrote it: 10002. “In the first row, instead of alternating black and white, suppose the first, say, eighty were white, and the next—what was it…” He checked the printout.

BTMP1000:2.80,24,341,55,500.80,24,342,54,499,1.80,24

“…twenty-four were black. And so on and so on for all the rows. What would you have?”

“A bloody great, stupid-looking chessboard,” said Fatboy, who was cool and popular but wasn’t really all that bright.

“A photograph,” said Rebecca, who was.

“Or a fax,” said Tane who, just at that moment, thought he was the brightest of them all. “A fax is just a lot of rows of black and white dots, arranged in a particular pattern to form a picture.”

“Brilliant!” Rebecca cried. She put down her computer and rushed into the control room. She threw her arms around Fatboy’s neck and gave him a huge hug from behind.

Hey, thought Tane, it was me who solved it!

“What should we do?” asked Fatboy. “Get a big piece of paper and start to draw it up?”

Rebecca shook her head. “It’d be easier to do on the computer. I’ll do it in Photoshop. I’ll just create an image one thousand dots by one thousand dots and save it as a…” She stopped, and then strangely, and rather tiredly, began to laugh again.

“What?” asked Tane, a little defensively, thinking she was laughing at him.

“Save it as a bitmap.”

It took Rebecca nearly two hours to take the data they already had and convert it into dots on the bitmap. All the weeks of data they had received and it made up less than a third of the image. It was clear enough from that what the image was going to be, though.

“It’s a diagram,” Rebecca announced from the main cabin, studying the image on the screen of her laptop. “A schematic.”

“Of what?” Fatboy asked.

“Of what the hell do you think?” Tane answered a little testily, his head still throbbing.

Rebecca said, “Easy, Tane. Of the gamma-ray time-message-sender device, Fats. I have a feeling that we are going to need this, sooner than we thought.”

“How soon?” Fatboy asked, but nobody answered.

Rebecca came back into the control room and, there being no spare seat, sat on Fatboy’s knee. Tane stared out of the viewing window of the sub. He said, “I think I have a name for it.”

Rebecca looked up. “Yes?”

“Well, it’s like a telephone that sends text messages through time, right?”

“Well, sort of.”

The name had floated into Tane’s mind in between throbs of pain. Tele was ancient Greek for “distance,” and phone was ancient Greek for “speech.” So a “telephone” was a machine that let you speak across a distance. The ancient Greek word for “time” was chronos.

“It’s a Chronophone.”

Rebecca said, “I like it.”

“Wouldn’t it be a Chronograph?” Fatboy asked. “I mean, it’s more like a telegraph, sending Morse code, than a telephone.”

“Maybe, but a Chronograph is a kind of watch, so I think Chronophone is best,” Tane insisted.

“Actually, Fatboy is right,” Rebecca said.

“Okay, whatever.” Tane shrugged and turned away.

There was an awkward pause. Fatboy coughed.

After a moment, Rebecca said brightly, “Chronophone will do fine. But what a paradox.”

Tane groaned, “Oh, here we go. I suppose you want me to kill Grandad again.”

“You killed Grandad?!” Fatboy asked.

“No, Fatboy, don’t worry about it. What paradox?”

“Think about it.” Rebecca’s eyes were wide. “We’re in the middle of sending ourselves plans for the Chrono…phone, right, from the future.”

“This much we know already.”

“But where did we get the plans from?”

“Which ‘we’ are you talking about?” Tane asked.

“Okay,” Rebecca said. “Call the future Tane and Rebecca ‘them.’ Now, where did they get the plans from? From us, right?”

“From us?” Fatboy queried. “How did we send the plans to the future?”

Rebecca sighed with exasperation. “We didn’t send them. We just hung on to them. Think about it. Tane and I are the future Tane and Rebecca, just not yet. So future Tane and Rebecca get the plans from us, but where did we get them from? From them!”

“So who had the plans in the first place?” Fatboy asked.

“Exactly!” Rebecca thundered, leaving Fatboy no more the wiser.

“And this has something to do with Grandad?” Fatboy asked, and couldn’t understand why Tane and Rebecca got the giggles.

“The plans must have come from somewhere,” Fatboy insisted.

“Maybe this is one of those kinds of questions that our brains just can’t comprehend,” Rebecca said, wiping laughter tears from her eye. “Like the infinite size of space. Or what existed before the universe.”

“Or why in automatic cars you pull the gear lever backward to go forward, and forward to go backward,” Tane contributed, and even Fatboy started laughing, in a confused kind of way.

Eventually Fatboy said, “Okay. So I don’t really get all this paradox stuff, and I don’t understand where the plans for the Chronophone came from, but did you guys ever think about what a weird coincidence this whole thing is?”

Rebecca, still sitting on his knee, twisted her head around to look at him. “Yeah, I know.”

She idly lifted off his cowboy hat and put it on.

Tane asked, “What do you mean?

Fatboy hesitated. “Well…”

Rebecca said, “He means that us, well, you really, Tane, thinking up the idea of receiving messages from the future, just at the right time to stop Dr. Green and her Chimera Project, is a very unlikely coincidence. Right, Fats?”

Fatboy nodded. “Did anything else unusual happen, when you thought up the idea?”

Tane asked, “Like what?”

“Like, did you see anything, hear anything…”

Tane shut his eyes, remembering. “There was a shooting star.”

Rebecca looked up sharply. “What?”

“The moment that I thought of the idea of messages from the future, I saw a shooting star. That’s it. Nothing else.”

Fatboy shook his head. “Maybe it wasn’t an ordinary shooting star. Maybe the shooting star was actually a thought from the future hurtling through the atmosphere in some cosmic ray from the depths of the universe just before embedding itself in your brain.”

Tane said, “That’s nuts.”

Rebecca was already adding it to the notebook where she kept the message dates and times. She spoke as she wrote. “Please remember to send a shooting star above West Auckland on the twenty-seventh of October at exactly nine-fifty-three p.m. That was the right time, wasn’t it?”

“Close enough.”

Fatboy grinned. “So maybe the whole thing wasn’t Tane’s idea at all.”

“Bite me,” Tane laughed. “I thought of it by myself.”

Fatboy said, “Sure, with a little help from the future and their intergalactic brainwashing machine!”

He put his arms around Rebecca’s waist and she leaned back into him.

Tane gritted his teeth. “I thought of the basic idea,” he said.

His annoyance must have shown because Rebecca said, “He was only joking, Tane.”

Tane snapped back, “Well, I’m sick of it.”

He regretted saying it immediately. The confines of a submarine were no place for bickering and fighting, but the words were in the open now and there was nothing he could do about that.

“Easy, Tane,” Fatboy said calmly.

Once started, it was difficult to stop, and his head was pounding.

“Easy! You blackmail us out of two million dollars, worm your way into our project, and start barking orders around like you’re running the show. And you tell me to take it easy.”

“Hey, Tane,” Rebecca said gently.

“No, stuff it!” Tane shouted. “And stuff you! None of this, the submarine, the money, none of this would be here if not for me, and you just weasel your way into everything and take it all!” Even Tane knew that it wasn’t the money that he was talking about.

“Chill out,” Fatboy said, his jaw set.

“I’m sick of it,” Tane cried, his voice suddenly hoarse. “I’m sick of it and I’m sick of you.”

“Enough!” Rebecca said suddenly and firmly. “That’s enough, Tane.” She stood and took Fatboy firmly by the hand and led him back into the sleeping cabin. She pulled the watertight door shut between the two compartments, pausing only to say, “We’ll keep out of your way until you’ve calmed down.”

The clang of the metal door and the whir of the wheel-lock turning were like a knife in Tane’s chest. For some reason, he had thought she would agree with him. That she would tell Fatboy to back off and remember that he was just a one-third partner and there only by the grace of Tane and Rebecca. Friends since forever.

But it hadn’t turned out like that at all.

“Crap!” he yelled suddenly at the top of his voice into the void of the water all around. “Crap!”

Then, after a quick consultation with the map, he changed course, just slightly.

It was a childish display of emotion. An ill-considered, impulsive thing to do.

And it probably saved their lives.