In January 1984, “Bandit 41,” Maj John “Grunt” Skidmore, joined the Red Eagles as Nathman prepared to leave to take command of VFA-132 “Privateers,” a squadron of F/A-18C Hornets aboard the aircraft carrier USS Coral Sea. Stucky took responsibility for writing the MiG-23 flight manual once Nathman left.

Skidmore was the first F-16 FWS IP to join the Red Eagles, joining Watley, Stucky, and Geisler as Weapons School IPs assigned to fly the MiGs. “Myers had established a precedent for FWS guys to go to the Red Eagles,” Stucky said, adding: “Getting people with experience of the primary weapons systems was a good idea because you had guys from the Aggressors who knew Soviet tactics really well, but didn’t know much about what the other communities did. Guys like Monroe Watley, ‘Buffalo’ Myers, Paco Geisler, and John Skidmore came in with great experience of different weapons platforms. We did the same with the Navy, hiring guys like ‘Rookie’ Robb and Orville Prins from the F-14, and George Tullos and [later] Marty Macy from the F/A-18.”

Stucky, by now the Red Eagles’ training officer, recalled:

Gennin had his way of doing things, but that’s not necessarily an unflattering thing. I built the training records from the ground up that showed what each [4477th TES] pilot had been taught. It was an example of how Gennin was taking the squadron from a safety standpoint into a mode that was more standard for the Air Force. Until then, the way that things had been run was indicative of the black world – some general gives a group of guys a charter, and says, “Go fly these MiGs.” He might sign a document to make that happen, but there were not going to be the same documented processes in place like there would in a normal squadron.

Gennin had also taken to personally approving the flying schedule for each day, and while viewed as increasingly autocratic, he was delivering tangible results. He spent time with Nelson, analyzing the resource requirements of the squadron and creating a vision of what he wanted. To make that happen, he worked with former Red Eagle, Maj Dave McCloud: “Marshall McCloud was running black world programs in the Pentagon, and he was instrumental in allowing me to do my job by loosening the purse strings. Without him we could not have done what we needed to do. He had good vision and knew where to find the money.” From a facilities standpoint, Gennin used the increased budget from McCloud to invest in new technologies to help make the Red Eagles more efficient. He couldn’t remember what the budget was, but he did recall, “money was not an issue.”

One such change was the use of computers, whose introduction brought about a range of benefits. One of them, Scott recalled, was “the proper tracking of the pilot’s qualifications on computer, making the grease board that I had used as head of STAN/EVAL look redundant and rather antiquated.” Technology also allowed Gennin to source state-of-the-art command and control (C2) equipment for his GCI operators. He had already turned his attention to the GCI function within the squadron, hiring a new GCI flight commander in the form of Capt Billy Bayer. Now Gennin ordered that the new C2 equipment be installed not at Nellis, but at Tonopah. It was logical, he reasoned, that the combination of a co-located GCI center and the best equipment available would allow him to create an IADS of the truest kind. The new site would take time to build and would not be ready before his departure, but with the help of McCloud in the Pentagon, he had sourced the equipment and got the ball rolling.

By May, two-star general Eugene Fischer had replaced Gregory as the TFWC commander. Fischer’s remit from Creech was almost a carbon copy of Gennin’s, only Creech had told Fischer to “clean up” the whole of Nellis and all its organizations. The real problem at Nellis was the Aggressors, who by now bore little resemblance to the initial cadre that Suter, Moody, and O’Neill had formed 11 years previously. When Fischer arrived, the Aggressors were experiencing 22.9 mishaps per 100,000 flying hours, whereas the TAC accident rate for the entire command was just 3.2 – without the Nellis stats to skew that figure, it fell to just 1.9.

Fischer later gathered the Aggressors in an auditorium at Nellis and minced none of his words. He told them that they were “a cancer on the side of TAC,” and that even Creech had told his wing commanders to “treat them like the plague.” He was there to cut the cancer out, he had told his packed audience, defying anyone to blame the 22.9 mishap statistic on emulating Soviet tactics and flying BFM. The mishap rate, he said, was down to “dumb shit pilots and dumb shit instructors.”

He finished the talk, which became a rallying point for the Aggressors and later became known as the “Heart to Aggressor Talk,” by promising them this: “Some of you are doing just an absolutely superb job and I couldn’t be prouder of you. But as a group, you stink. And you gotta’ crawl out of the shit so you don’t smell no more … but I am not going to lose any more F-5s. I am not going to have any more F-5s go out of control. And if you do, you’d better have another God-damned career planned, because it’s not going to be part of the Air Force. I’ll do everything I can to run you out on a God-damned rail.” Unsurprisingly, the Red Eagles were distancing themselves more and more from the Aggressors at Nellis.

At Tonopah, the number of F-117s and the operational tempo of the 4450th TG gradually increased. Since few of the 4477th TES had been read in on SENIOR TREND, the activity at the north end of the base was intriguing indeed – more hangars were being constructed and the buildings had started to receive the two-tone paint scheme so popular at the time. When Geisler had asked Gennin what was going on, his boss had responded evasively, “The Air Force is coming.”

The Air Force’s arrival resulted in the Red Eagles maintainers moving out of the Indian Village trailers behind the MiG hangars. The F-117’s money had paid for the development of what was called the Man Camp, located about 6 miles north of the base and accessed via a single, straight asphalt road. Actually, the Air Staff had provided the funds for the Man Camp, but had routed it via Nelson (making it appear as though it was being paid for by the 4477th TES).

Man Camp was opulent by comparison to the trailers that had been home up until then. It had permanent accommodation, and bars and chow halls and a bowling alley for the officers and enlisted men. It even had an Olympic-size swimming pool. While the maintainers spent some time at Man Camp, the pilots rarely stayed overnight unless the next day’s schedule dictated it. When they did, they often left with more questions than answers, as Geisler revealed:

At the Man Camp, I would bump into guys that I knew who were now working for this other unit. They would tell me, “I can’t talk about what I am doing,” but they always wanted to come down and see our airplanes. I would say, “Fuck you! You can’t tell me what you’re doing; and even if you can see, I can’t tell you what we are doing!” Eventually, one of them got a release for me to go down there one night. It was pretty impressive: I walked in the hangar and said, “Holy crap. Does the cover come off? Is there a fighter in there somewhere underneath?” They said, “Kiss my ass!” We then started letting them come down to our hangars for a look at the MiGs.

Operationally, the F-117 pilots had even taken to using the Bandit call sign associated with the Red Eagles, a measure designed to ensure that their radio transmissions, which could be intercepted by a basic handheld scanner, did not sound out of the ordinary. In fact, the SENIOR TREND pilots had started assigning Bandit numbers to newly qualified pilots, too.

Geisler devised an interim solution for those pilots on the squadron not yet briefed on SENIOR TREND to get a look at the strange aircraft. “We would get lawn chairs and go out there at midnight and sit in the corner of our ramp. They would be asking what the hell they were doing, but I would tell them to be patient. Then all of a sudden this big old ‘Doober’ [F-117] would go by and they would just about fall out of their chairs.”

In March 1984, “Bandit 42,” Maj Thomas E. “Gabby” Drake, an F-16 Wing Weapons Officer and F-4 FWIC graduate, joined the Red Eagles and quickly qualified in the MiG-21. “At the beginning of 1984, I don’t think that the Red Eagles had any F-16 experience in the squadron. They had brought in John Skidmore, and I followed shortly after. That’s basically how I got into the unit.”

Drake was followed in April by two more new faces: Air Force captain Robert E. “Goldie” Craig became “Bandit 43,” and Navy pilot LtCdr Daniel R. “Bad Bob” McCort became “Bandit 44.” As they went methodically and slowly through a carefully created TX syllabus with their Red Eagle IPs, another man was about to rush that process. It would cost him his life, and would serve as a lesson to future Red Eagles pilots.

On April 26, LtGen Robert “Bobby” Bond, the vice commander of AFSC, was killed when he lost control of the MiG-23MS FLOGGER E he was flying. The MiG was one of those “belonging” to the Red Eagles, and had been temporarily loaned to the Red Hats. “Bond was about to retire, and he put word about within Systems Command that he wanted to fly the FLOGGER. Now, Systems Command owned a unit [Red Hats], that flew that type of MiG, and so that is where it all happened. I would have done my very best to convince Bond not to fly. The guy was about to retire, and this was his ‘going away’ present,” said one Red Eagle, while another said, without sympathy, “He should have read the flight manual.” Others were less critical: “I would have said to him, ‘General, you do not want to do this.’ But if you say this to him and turns around and says, ‘Thanks. Now, let’s go fly the airplane’, then what are you going to do? It is your job to salute smartly and then go make it happen.”

Bond was making a high-speed run, the second of two orientation flights, when the incident occurred over Area 25 of the Nevada Test Site. He was the same Bond who had ushered Peck into his office in 1976 and shown him the HAVE BLUE file. His orientation sorties were part of what appears to have been a farewell tour of AFSC’s black world. In March he had visited Groom Lake for two orientation flights in the full-scale prototype of the Stealth Fighter, the YF-117A.

It is alleged that Bond had insisted on a simple briefing on the supersonic handling characteristics of the Flogger from a pilot sitting on the canopy rail. Compared to what was the official TX course at the time, that decision appears to be particularly ill advised. The MiG-23 TX course consisted of a taxi sortie to familiarize the pilot with ground handling, and then six flights – three for familiarization, two to become acquainted with the MiG-23’s systems, and a sixth ride to be formally checked out in the jet. This syllabus was based on the TX course no doubt put together after the completion of HAVE PAD, and is dated November 1, 1979, according to the official Air Force Safety Center mishap report. Instead of in-depth academic classroom study and supervised sorties that had been created and approved by test pilots of his own command, Bond had opted for an expedited explanation of the MiG’s operating procedures that was insufficient by the standards of the briefest of TX syllabi. “TR 1 was a general transition sortie; maybe some basic aerobatics, and then return to the pattern for lots of landing practice to get a feel for it. TR2 was the supersonic run, and that’s what General Bond was doing when he died.”

At 40,000ft, the Flogger’s powerful engine pushed the aircraft beyond the sound barrier, leaving his T-38 chase lagging miles behind. “That is not the way to chase a MiG-23 with a T-38,” said one. “The T-38 can only get up to about Mach 1,15, and this T-38 chase lost sight of the FLOGGER,” He explained:

You run the Flogger to the edge of the airspace while the T-38 drops to 3 miles in trail. When the MiG gets to the boundary, you do an in-place 180 degree turn that then puts the T-38 3 miles in front. You light the burners, and after a couple of minutes the Flogger blows past you. By the time you get to the next boundary, he’s 3 or 4 miles in front of you – but you can still see him. You bring him back in a big turn, then cut across the big circle he’s making to draw level with him again. You had to start with the T-38 well out in front of him, or you were going to lose him.

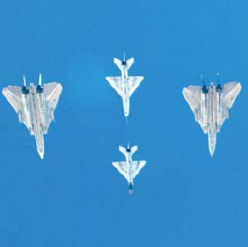

Two 64th FWS F-5s formate with a 4477th TEF MiG-17 (leading) and MiG-21 (trailing). The MiGs transferred from HAVE IDEA were all finished in a natural silver, but of note in this photograph from c.1979 is the TAC badge applied to the vertical fin of the MiG-21, clearly identifying its new owner! (USAF via Steve Davies)

A 4477th TEF MiG-21 taxis back to parking at Tonopah. Presumably a still image taken from a cine film, the Fishbed is seen carrying a center line fuel tank – an unusual sight for a Red Eagles jet. (USAF via Steve Davies)

The US Navy had been a major proponent of MiG exploitations since HAVE DOUGHNUT in 1968. Here, two Navy F-14 Tomcats bracket a pair of smaller 4477th TEF MIG-21s in a photo dated c.1980. (USAF via Steve Davies)

Construction of the MiG-23 hangars commenced around 1982. This aerial photograph shows the ground north of the MiG-21/MiG-17 hangars being flattened and compacted before the structures were erected. (Lenny Bucko via Steve Davies)

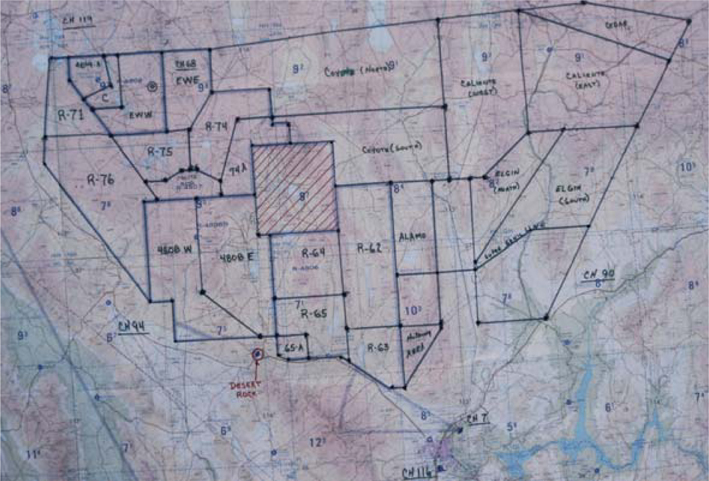

The Nellis and Tonopah ranges are shown clearly in this 1982 photograph of the 4477th TES’s airspace chart. The red hatched mark in the middle is Area 51, while Tonopah is located in the far northwest of the map and is labeled 4809-A. Nellis. (Lenny Bucko via Steve Davies)

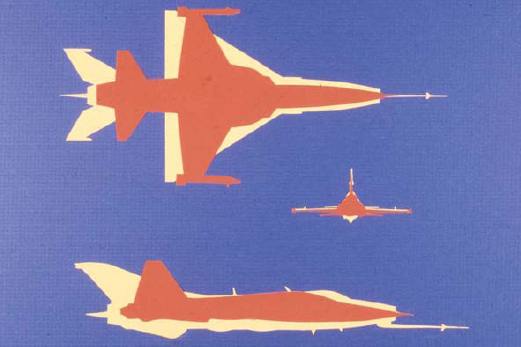

The Red Eagles compiled a number of classified briefing slides to show visiting TAF pilots. This one compares the relative dimensions of the F-5 (red) with the MiG-21 (yellow). (USAF via Steve Davies)

In June 1979, TAC executed a counter cover operation in an attempt to hide the true purpose of the recent renovations at Tonopah from Soviet satellites. This F-86 Sabre was just one of the aircraft flown from the bare base as part of that effort. A month later the first MiGs arrived. (USAF via Steve Davies)

The Fishbed’s two dorsal speed brakes and the starboard cannon port are clearly visible in this c.1987 image of a Red Eagle MiG-21. Less obvious is the black navigation aerial, which was one of the few external modifications made to the MiGs by the USAF. (USAF via Steve Davies)

LtCol Earl Henderson (in the cockpit of the F-5) formally takes command of the 4477th TEF following Gail Peck’s dismissal. Prior to his new appointment, Henderson had been the 64th FWS operations officer. (Earl Henderson via Steve Davies)

Aileron rolls in the MiG-21 could be exciting if the pilot failed to blend in rudder inputs gently. IPs throughout the history of the 4477th TEF/TES would allow their students to learn this lesson the hard way! (USAF via Steve Davies)

Red Eagles maintainer Billy Lightfoot could fix anything with a motor and wheels. This c.1981 photograph at Tonopah showcases just a few of his improvised vehicles. (Lenny Bucko via Steve Davies)

One of only two surviving contemporary photos of a 4477th TES MiG-23MS Flogger E. The enlarged spine of the vertical tail was intended to work in tandem with the extending dorsal spine (folded away in this photo) to help reduce the jet’s tendency to yaw from left to right in high-speed flight. (USAF via Steve Davies)

Capt Mark “Toast” Postai’s MiG-23 model. Custom made and painted to the last detail (note red stars with yellow boarders), it is poignant that the young fighter pilot chose “Red 23” to be painted on the nose – the very Flogger in which he was killed. (Linda Hughes (Postai) via Steve Davies)

Mark Postai’s models and Aggressor flight helmet (left to right): MiG-21, MiG-17, F-5 and MiG-23. These models helped Linda Postai put together the pieces of the puzzle following her husband’s tragic death. (Linda Hughes (Postai) via Steve Davies)

Maj Karl Whittenberg straps into the front seat of a T-38 at Tonopah. The T-38s were vital for the “clean and dry” checks that were performed on the MiGs immediately following take-off – an event that soon turned into a competition to see who could join formation the quickest and closest! (Lenny Bucko via Steve Davies)

Until the 4477th TES was able to acquire its own T-38 Talons, it borrowed examples such as this 57th FWW Aggressor jet. (Lenny Bucko via Steve Davies)

4477th TES maintainers board one of the Red Eagles’ Cessna 404s for the early morning flight from Nellis to Tonopah. (Lenny Bucko via Steve Davies)

MiG-21F-13 “Red 84” taxis past the tower at Tonopah. Dated approximately 1986, this was one of the last of the Indonesian F-13s retired by Manclark. It carries the USAF serial number 11 on the nose landing gear door. (USAF via Steve Davies)

The MiG-21F-13 cockpit left much to be desired from an ergonomic standpoint, but equally as alien to the American pilots were the “kumquat gauges,” which measured parameters in unfamiliar units – kilograms, liters, etc. (USAF via Steve Davies)

An early photo, probably from the early 1980s, showing an FWIC F-16 and a MiG-21F-13 in flight. The Weapons School was one of the first to benefit from CONSTANT PEG. (USAF via Steve Davies)

A 4477th TES T-38 Talon sits on the ramp at Tonopah in the midday sun. The eventual acquisition of four Talons by the Red Eagles made life considerably easier. (USAF via Steve Davies)

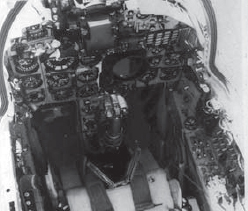

The white line down the instrument panel – so important when recovering from uncontrolled flight – is visible in this wide angle view of one of the Red Eagles’ Indonesian Fishbeds. (USAF via Steve Davies)

Photographed in the mid-1980s, a 4477th TES Indonesian Fishbed C/E poses for the camera. Note the intake cone fully retracted for subsonic flight. (USAF via Steve Davies)

Z-Man Zettle stands in front of Ted Drake’s MiG-23MS Flogger E, “Red 49.” When he left the unit Drake remarked that “the MiG-23 would try to kill you on every sortie, if you let it.” With 294 sorties in the interceptor, he was the 4477th TES’s most experienced Flogger pilot of all time. Note the pentagon-shaped maintenance emblem on the nose. (USAF via Steve Davies)

LtCdr Cary “Dollar” Silvers unstraps from the front seat of his F-14 Tomcat during a visit with his parents at NAS Atlanta in 1982. Four years later he would be flying MiGs at a secret desert location. (Cary Silvers via Steve Davies)

The MiG-23 throttle had a mechanical lock which prevented the throttle from being inadvertently retarded at high Mach numbers. This, combined with a speed coast down interlock in the engine, prevented sudden decelerations that could rip the motor from its mount. (www.fjphotography.com)

The MiG-23 front panel, with white stripe down the center to assist the pilot in neutralising the control stick during out-of-control flight. Even from an elevated angle, this photograph demonstrates how poor the visibility ahead was. (Steve Davies, www.fjphotography.com)

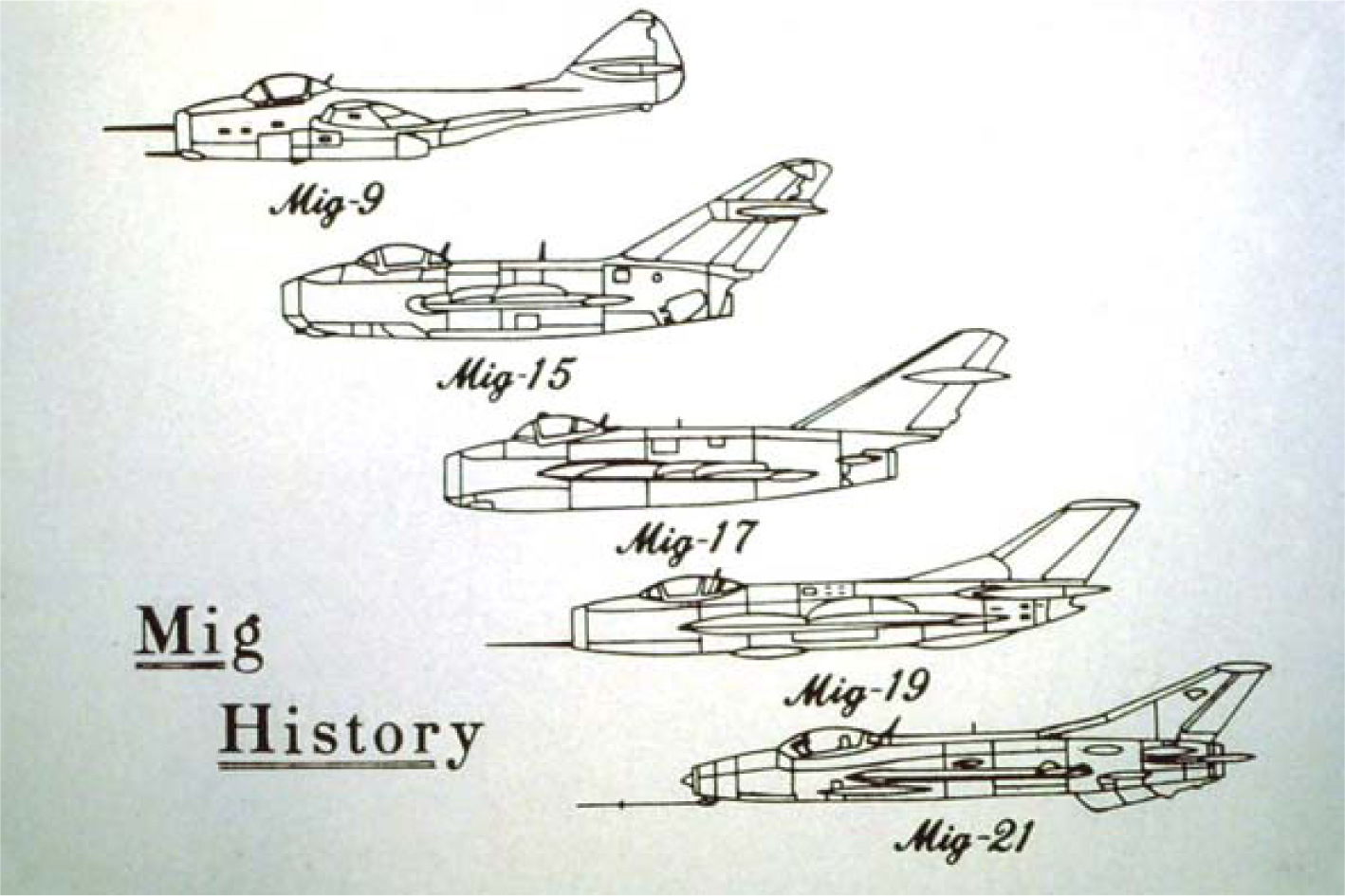

A 4477th TES briefing slide shown to visiting TAF pilots; it charts the progression of the MiG family of fighters. (USAF via Steve Davies)

LtCol Jack Manclark poses in the VIP hangar with the 4477th TES Red Eagles pilots, intel officer and GCI controllers in c.1986. The Fishbed, “Red 85,” is an Indonesian MiG-21F-13 with a USAF serial 14. (USAF via Steve Davies)

Returning to base meant flying over a number of roads and dirt tracks, but most of these fell within the controlled airspace of the Tonopah Test Range, and the MiGs maintained sufficient altitude in case of an engine flameout that they were very difficult to see in any case. (USAF via Steve Davies)

The Old and the New. A green, black and gray MiG-21F-13 (left) of Indonesian origin sits alongside a white Shenyang J-7B in late 1987. This particular F-13 was retired to the Threat Training Facility at Nellis, where it stayed for many years. (USAF via Steve Davies)

Photographed between 1987 and early 1988, a Chinese-built Shenyang J-7B Fishbed lands at Tonopah. (The scratch and attempts to touch it up were conducted before the image was released to the public.) (USAF via Steve Davies)

The MiG-21 wasn’t a “vertical” fighter, but its slow speed capabilities meant it could be looped at much lower airspeeds than any American fighter if the need arose. (USAF via Steve Davies)

When the US Air Force declassified a small selection of Red Eagles photographs, this image was inadvertently included. It shows the cockpit of a MiG-21MF, and its inclusion in the cache of images supports the possibility that the 4477th TES did indeed operate this marque of Fishbed. (USAF via Steve Davies)

“Red 96,” a Chinese-built J-7B with the USAF serial 47 on the nose landing gear doors, was one of the last MiGs acquired by the 4477th TES before its closure in March 1988. (USAF via Steve Davies)

Now painted in silver and positioned outside the 64th FWS at Nellis, this MiG-21F-13 is a former 4477th TEF/TES example and can be seen in the middle photo on the previous page wearing a black and green camouflage scheme. It is rumored that this aircraft was the first of the Indonesian Fishbeds, and had USAF serial 004. (Neil Henderson via Steve Davies)

Adorned with the name of LtGen David McCloud, a former Red Eagle who was killed flying his aerobatic Yak-54 over Alaska in Jul 1998, this MiG-17F Fresco C is believed to be HAVE DRILL. It is now located outside the TTF at Nellis AFB. (Steve Davies, www.fjphotography.com)

A view through the cockpit glass of the MiG-21F-13 on display at the Eglin AFB Armament Museum, Florida. Note the US G-meter (far left). Many of the instruments carry English language placards. (Steve Davies, www.fjphotography.com)

The right side console of the Eglin MiG-21 shows the red and yellow striped handle of the Fishbed C/E SK-1 Canopy Capsule Seat. Another handle was installed on the other side of the seat, and both had to be squeezed and pulled upwards to initiate ejection. (Steve Davies, www.fjphotography.com)

There is strong evidence to suggest that “Red 85,” the Fishbed C/E at Eglin, is the former 4477th TES VIP hangar MiG-21F-13 (USAF serial number 14) from Tonopah. This aircraft was repainted on arrival at Eglin, but I was told it was repainted identically. This aircraft simply “arrived at the museum overnight,” and the curator was told not to ask any questions. (Steve Davies, www.fjphotography.com)

The wing sweep lever in the MiG-23, with detents at the 16-, 45- and 72-degree positions. (Steve Davies, www.fjphotography.com)

The MiG-23 featured a dorsal fin that folded upon lowering the undercarriage. Lenny Bucko had wondered how any pilot could manage to grind the fin off during landing, but all became clear when he managed to do exactly that months later! (Steve Davies, www.fjphotography.com)

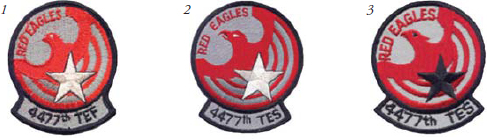

The original 4477th TEF patch, designed by Navy pilot LtCdr Chuck “Heater” Heatley and approved as a result of Maj David “DL” Smith’s efforts at TAC HQ, Langley AFB (1). When the Red Eagles were elevated to squadron status, the patch was changed to reflect the new “TES” status (2). Over the years, the patch was modified very slightly (compare the Eagle and the background colours with the 4477th TEF patch), and this is a scan of the last ever official batch. It was taken from the vault at Tonopah in March 1988 by Maj James “Tony” Mahoney and given to the author in mid-2007. When Col George “G2” Gennin ordered the maintainers to wear official Air Force uniforms, a revised copy of the 4477th TES patch was created to include a low-conspicuity black star (3). The officers continued wearing the version with the white star. (Steve Davies’ collection)

The speed Bond was now traveling at remains classified, but was presumably beyond Mach 2. He was about to enter a part of the flight envelope in which a number of complicated phonemena would take place.

As the aircraft continued to accelerate alarmingly quickly, a hydro-mechanical inhibitor called the “speed coast-down interlock” became energized that prevented the engine from throttling back, even if the throttle in the cockpit was physically retarded. Bond could move the throttle back to halt the acceleration if he wished, but the engine was not going to respond, and would not even have come out of afterburner.

In fact, the throttle itself operated in an idiosyncratic way: “To go into burner you pressed a finger lift to enter the burner range; to enter full burner, you repeated the process. To come out of full burner you once more pressed the finger lift, and then to come out of burner altogether you depressed the finglift once more,” one pilot explained.

Of the speed cost-down interlock, he said:

For the air model FLOGGER, if you were going 1.5 Mach or faster, the wings were undoubtedly at 72 degrees and the spoilers had completely phased out. Your roll is now completely controlled with differential stabilator. As you go through 1.7 Mach, you bring the throttle to idle. You watch the engine run down to 97.5 percent +/- 1 percent, but then you have to sit there and watch it remain there until you reach 1.5 Mach. That took a long time in the FLOGGER – in ten seconds or so you might only be down to 1.68 Mach, then another ten seconds later it’s at 1.66 … it took a very long time. Usually, I’d bring the nose up to 20 degrees to get it to slow down below 1.5 Mach. Once you were finally below that, the engine would then roll to idle, but with a tremendous deceleration.

Thus, the interlock was there to ensure that the pilot could not decelerate so drastically that the R-29 would tear free of its mountings, causing a catastrophic explosion.

To make matters even worse for Bond: “With the wings back at 72 degrees,” Matheny offered, “you would run out of stabilator authority to control the pitch of the nose. You just became the classic bullet. Above Mach 2 it didn’t want to turn at all.” Matheny said he’d flown the MiG-23 up to Mach 2.5, which may have been slightly faster than the target speed for Bond’s test flight.28 The difference was that Matheny had been extensively prepared for the experience.

Bond was now in real trouble. He was at more than twice the speed of sound, had very limited pitch authority, was accelerating to the placarded limits above which the canopy threatened to melt or implode, and was unable to get the MiG to slow. The solution lay in understanding two things: firstly, that the interlock would gradually reduce the thrust output, and to decelerate the jet by pulling back on the stick and waiting for the nose to rise above the horizon, which would help the airspeed to decay sufficiently for the inhibitor to disconnect; and secondly, he was about to experience a startling aerodynamic peculiarity of the MiG-23.

That peculiarity was called “air intake buzz.”

This was a compressor stall in one of the intakes, but not the other. It caused so much drag that it caused a yaw that brought the opposite wing forward. Because this wing was at a little higher angle of attack, it had more chordwise airflow and therefore produced lift that created a constant roll. With that much drag, the differential stab and opposite rudder would not have been sufficient to stop the roll. You could do one of two things: if the roll were slow enough, you pulled the stick to get the nose up in the air to slow down, get the wings forward and then use spoilers to stop the roll. If you couldn’t do that, and because pulling the throttle to idle was not going to slow you down that much, they said you had to bring the throttle to cut-off [i.e. remove fuel flow to the engine]. Yes, it could have damaged the engine, but the alternative was almost certain death.

Having left his T-38 safety chase for dust, Bond transmitted that he had lost control, perhaps experiencing the unresponsive engine and air intake buzz at the same time. “I gotta get out of here,” he exclaimed. Seconds later he ejected. “The airplane was rolling; he couldn’t stop it. He probably didn’t even know how to because he didn’t have any academics. So he ejected out of the thing going really fast.”

The supersonic slipstream caught the lip of his flight helmet (although it is said that the airflow going over the top of the helment produced enough lift to violently pull his head upwards), causing the chinstrap to instantly tug his head backwards over the back of the ejection seat headrest. He died instantly from a broken neck and fell to earth beneath a tattered, shredded parachute. “A passing Air Force Sgt was driving to work on the Indian Springs highway. He sees the parachute coming down and drives off-road to where it lands. He finds General Bond, dead, and sees the three silver stars on his shoulders. He doesn’t know what to do, so he uses his pocket knife to cut Bond’s rank insignia from his flight suit. That way, if anyone finds him, they won’t know he’s a general. He then goes off to get help – remember, there were no cell phones in those days. That’s how they find him.”

The MiG-23 itself impacted the ground at an angle of 60 degrees, apparently with the engine still running just below military RPM and with no other indications of flight control, structural, or systems failure evident to the mishap investigating team. So classified was that mishap that the subsequent investigation was chaired by none other than the commander of the Air Force’s Inspection and Safety Center, Gen Gordon E. Williams.

Some Red Eagles were angry about Bond’s actions. He may have been a great pilot and commander, but flying the MiG-23 – a national asset – when he was about to retire was something that many felt he had no business doing. Unlike other mishaps, there was no fallout at the highest levels as a result of this crash, probably because of Bond’s rank; his boss was a four-star general. However, according to one source, the Red Hats commander, LtCol James Tiley, became what could be argued to be a scapegoat when he was relieved of command in July (although Merlin maintains that Tiley’s command of the Red Hats did not end abruptly or early). Whatever, Tiley returned as base commander of Groom Lake in spring, 1987. In the years that followed, the Red Eagle MiG-23 pilots were encouraged to read the secret mishap reports.

One pilot mentioned that there might have been an alternative explanation for Bond’s mishap. “I was flying a functional check flight one day. The intake ramps in the FLOGGER sequence automatically to control airflow to the engines. On this day, one of them failed while I was supersonic. The aircraft yawed and rolled, and I couldn’t stop it. I had full stick and rudder to the left, and it’s rolling right. I just thought, ‘Bobby Bond.’ Even though I had a lot of flights in the airplane, I remember saying to myself that I did not want to shut this engine down. It rolled completely and then stopped, but after that day I did wonder whether or not it was a ramp problem that he’d had.” After that, pilots were encouraged not to exceed 1.8 Mach on a routine basis.

With the wing-through box problems recurring intermittently, the main issue affecting the Red Eagles’ MiG-23s remained the continuing shortage of Tumansky R-29 motors. Complicating matters was the fact that “the air and ground models had different motors. The R-29-300 for the E-model, and the R-29B-300 for the F-model: “They were different sizes, had a different number of first stage compressor blades, and were mounted differently in the airframes,” said Drake. The maintainers did all that they could to keep the troublesome jet in the air. “They were a beast to work on, especially pulling an engine. We called them Javalinas, after the wild pig found in Texas,” said Rick Wagner, a Red Eagle maintainer who replaced Jerry Bickford in the avionics shop in 1984. As more Floggers arrived the maintainers gave them nicknames that mocked their status as pigs but were also a term of endearment. “One was called ‘Miss Piggy,’ after the famous character in The Muppet Show, and another was christened ‘Arnold,’ the name of a pig owned by the Ziffle family on a popular 1960s US comedy show Green Acres,” Wagner enlightened. Drake added, “We called all the MiG-23s Hogs because they were a Hog to fly.”

Postai’s October 1982 crash resulted in a long grounding for the Flogger, said Matheny, but the unreliability and need for constant maintenance meant that little had changed. The MiG-23 Bond had been flying when he was killed had Air Force records dating back only three years (to 1981) that showed it had flown for only 98.2 hours in that time, and that in the three months leading up to the mishap, it had flown barely an hour a week.

Some of the problems arose from unfamiliarity with the techniques employed by Tumansky, and the difficulty GE faced in reverse engineering them. “There were things about the motor in it that we just hadn’t seen before,” Shervanick pointed out. “For example, the turbine blades had tiny air passages running through them that allowed cooling air through to keep the motor cool. It ran so hot that this was important. We were also not used to the size of the compressor blades at the front of the motor, or the amount of twist that was on them.”

While innovative, these techniques for keeping the engine cool were also its Achilles’ heel. Whereas Western engine manufacturers used long-lasting coatings to prevent their turbine blades from melting in the extreme heat of the turbine section, the drilled Tumansky blades had a very limited life. “These motors had never been intended to fly this many hours,” recalled Shervanick, who was by now an experienced Flogger pilot by 4477th TES standards, and the Red Eagles’ MiG-23 FCF pilot. “They were good for a couple of hundred sorties at most, and it was part of Russia’s way of making money that they would sell new engines to their export customers for hard currency.” In addition, because the R-29A ran extremely hot, the fleet was plagued by false alarms when the temperature sensors in the engine bay of the gangly jet would reach a critical temperature, thus energizing fire warning lights in the cockpit. Such an indication resulted in an immediate “Knock it off!” call and return to TTR.

Each fire warning light activation was treated with the utmost caution and respect, and following a thorough inspection on the ground the aircraft in question would have to be flown on an FCF sortie before it could be released back onto the flying schedule. On one occasion, Shervanick had to fly three FCF sorties in a row on the same Flogger when the fire warning light illuminated on successive flights. “It felt like every day one of the MiG-23s had a fire warning light come on,” Geisler reflected. Ironically, recalls Zettel, who would amass 138 sorties in the MiG-23, “it was typically the US system – I think taken from a KC-135 – that gave us all the false alarms! It was so poor, like the boy crying wolf, that I ended up taking one guy aside and telling him that if we wrote up every alarm we’d never fly the things. I don’t think that was reckless, it was just because I knew the airplane.”

A month after Bond’s mishap, Watley left the Red Eagles, running naked from his MiG following his final flight as was now customary, according to Nelson. But like several other ex-Red Eagles, Watley wouldn’t be away from CONSTANT PEG for too long. His immediate assignment was Air Command & Staff College, which would take a year or so, but he was then slated to become the Pentagon’s program manager for the Red Eagles. He was a big character who would be missed. Nelson said: “When he’d meet you he’d say, ‘Hi! I’m Monroe Watley, the world’s greatest fighter pilot!’ His smile was as big as Texas.” Watley and Nathman had become close friends during their time on the squadron. “He was an incredible pilot, in the air and on the ground,” Nathman said. “Just the way he prepared for missions showed you that. He was a joy to be around, and everyone looked at him as the consummate professional. At one time, Monroe and I were the only guys flying the Flogger. There was one experienced guy who had just left, leaving the two of us without a whole lot of time in the jet.”

Since Bucko’s three-point landing in the MiG-23, the aircraft had been subject to a 23-knot crosswind landing limit. One day, Nathman and Watley tested that figure. Nathman recounted: “I landed with the crosswind right on the limit. It was gusty, but I decided to put the drag ’chute out anyway. One wing started lifting up under the crosswind, and the drag ’chute in the MiG-23 only aggravates that. So, I started being pulled across the runway and ended up running into all the runway lights with my nose gear. I was holding the stick all the way over to the right to keep the wing down, but the drag ’chute release handle is way over on the left, so I was having a problem reaching it. I eventually got it stopped, having scared the shit out of myself.”

It turned out that none of the runway lights had broken, so there was no glass in the nose wheel tires of Nathman’s jet that would serve as evidence for his embarrassing landing. “About four days later, Monroe and I were sitting down having an beer. He said to me, ‘Hey! Black, you know that crosswind limit on the [MiG-] 23? I think it should be lower!’ It turned out that he had done the exact same thing as me the day before. He hadn’t told me and I hadn’t told him. We both looked at each other and started drinking heavily; we then knew that we would have to compare notes more frequently.”

Watley’s departure coincided with some good news, though. “Bandit 22,” Marine Corps pilot Lenny Bucko, had by now returned from his ground tour to assume a three-year posting as executive officer (XO) to an F/A-18 Hornet squadron based at El Toro. He would once again be involved in CONSTANT PEG. “I made several trips to Tonopah in the Hornet, and I remained on the Clearance List for about eight years to help make it easy to coordinate short notice [exposure] flights with the Marines, and to be able to get the Corps more than their share of sorties.”

Bucko’s association with the 4477th TES had followed him to Japan, where it had stood him in good stead. He had arrived on the Japanese island of Okinawa for his ground tour to find that 18th TFW – which consisted of two squadrons of F-15s – was commanded by none other than Peck. The two had got on well, and Peck had arranged for Bucko to give tours of the MiG-23 in the classified Warrior Prep center on base. Bickford and some of the other Red Eagles maintainers had transferred the Flogger to Japan in great secrecy, flying with the disassembled MiG in the back of a C-141 Starlifter transporter, and then reassembling it once it had been transferred in secret to the inside of the facility (another MiG-23 had been transferred to the USAFE’s Warrior Prep center at Einsiedlerhof AB, Germany).

Less pleasant were the problems he was now experiencing with the Internal Revenue Service (IRS), which queried his tax return from 1982 and insisted that he explain some of the more peculiar expenses that he had claimed. “They told me I either told them what they were for, or I would have to get a letter from the general.” He got a letter explaining his expenses were bona fide, but the IRS paid him close attention for another two years nonetheless.

Meanwhile, Saxman was converting to the Flogger under the tutelage of Matheny. On only his third flight he had just rotated the Flogger’s nose when there was a bang and the cockpit filled with smoke. “Thug’s on my wing and he can’t see me in the cockpit. He starts talking to me: ‘Roll left,’ ‘Roll a little right,’ ‘Keep the nose coming up.’ I’m looking at the instruments, but we didn’t maintain them for flying IFR [instrument flight rules], so they are almost useless. Then I realize that it’s not smoke – it’s condensation. My glasses, visor and the canopy are covered in a fine mist. I wipe my glasses, raise my visor, and wipe the canopy either side, but I can’t reach far enough to clear directly in front. Thug takes the lead and I fly formation on him just looking out of the side window. He lines me up on short final and drops me off just at the point where I can see the runway out of the side.”

As spring gave way to summer, Gennin was reaching the end of his two-year command and prepared to hand over the squadron to his successor, LtCol Phil “Hound Dog” White. Gennin was off to War College. He was pleased with what he had achieved and was ready to move on to the next challenge, but he was less than excited about going back to school. White arrived in June to learn to fly the MiG-21, along with Air Force captain Timothy R. “Stretch” Kinney. Kinney qualified first, becoming “Bandit 45,” followed shortly thereafter by the new commander, “Bandit 46.”

In July Gennin handed over the reins to White. White was a charismatic man who was fond of the ladies and had been one of the initial cadre at the 26th TFTS at Clark. He had worked for Roger Wells, knew Scott, Shervanick, and Henderson from the Philippines, and had come to know most of the other Red Eagles, past and present, through his ongoing Aggressor work. He was a completely different leader from Gennin: more laid back, more willing to empower his pilots, and less autocratic. But he too would be controversial: there was still much change to bring about, and while Gennin had accomplished much during his two years at Tonopah, CONSTANT PEG still had untapped potential.

White was well connected at TAC, and was known even to Creech before he was given control of CONSTANT PEG. He had worked a staff tour at TAC HQ, Langley, in the summer of 1981. There he attained the rank of lieutenant colonel and was a division chief in the office of the Director of Requirements, but he had soon been promoted to XO for two-star Director of Requirements:

I was interviewed twice for squadron command while I was there, but one of the squadrons I was going to get was closed down and its F-4s given to the Turkish Air Force; and the other, an F-16 squadron, never happened because I got a call from the secretary of Gen Mike Kirby, the one-star wing commander for the 57th Fighter Weapons Wing at the time, asking if I could attend an interview.

I was now confused, and I asked my boss what was going on. He told me he knew all about it: “Just shut your mouth, go to Nellis, and interview.” He knew what unit it was, I did not. At that time, Mike Scott was doing the black world job for the two-star TAC DO, who was really the general who ran CONSTANT PEG. Mike [helped arrange my TDY to Nellis] and told me what was going on.

White interviewed first with Kirby and then with the TFWC commander, Fischer. He knew Fischer from his F-4 days, and the two-star told him that he would probably have to meet Creech for final approval. But since the TAC commander already knew White and had endorsed his last two performance reports, Creech waived the final interview and approved the position.

In August, Green left the squadron as White began to make some initial changes. The first, which brought a sigh of relief to those who disagreed with Gennin’s policy of curtailing the duration of maintenance tours, was the reversal of the three-year limit. The other was to hand back responsibility for the daily flight schedule to his ops officer, Bland.

But before White had properly got his feet under the table, the 57th FWW’s new commander, Gen Joe Ashy, took the decision to prohibit Skidmore, Stucky, and Geisler from flying any more Weapons School sorties. This angered both the pilots and the Weapons Schools, and resulted in Skidmore asking for reassignment, as Geisler explained: “When Ashy told us we couldn’t maintain our dual currency in the school and ‘up north,’ ‘Grunt’ asked if he could instead go back to the Weapons School. It was a career decision, and they granted him that choice.” He would be allowed to move back to the F-16 FWS in due course – Drake reckoned about a year or so – but not immediately.

Ashy and White were friends who knew each other already and frequently drank together as members of the covert Air Force social club, “The Bar Stoolers,” but this was the start of a turbulent working relationship between the two. White was a West Virginian who had joined the Air Force’s ROTC program, graduated pilot training and had gone straight to the F-4. There, he’d had the misfortune to spend his first combat tour in Vietnam flying from the backseat of the F-4 – a policy that affected all of the pilots going to the F-4 straight from UPT at that time. After six months he had been upgraded to fly from the front cockpit, and had eventually flown the F-4E with the 4th TFW, Seymour Johnson. In January 1975, he had been picked out of a tour flying the F-4E in Japan to help stand up the 26th TFTS Aggressors. Two years later he was a flight commander with the 65th FWS at Nellis. He had progressed to the TFWC as the then wing commander, Chuck Cunningham’s, XO. When Brown had died, White was assigned to the 64th FWS as its ops officer, replacing Henderson, who had gone to take over the Red Eagles.29

By the time White arrived at Tonopah, news of the decision to deny Scott a DFC had reached the vice commander of TAC, who happened to be the former TFWC commander and recently promoted three-star general, Robert Kelley. Fully aware of the details stripped from the unclassified write-up, Kelley called the board and personally recommended that they award the medal. Tim Kinnan, Kelley’s XO, and John Jumper, Creech’s XO, were also instrumental in helping push the award through, said Scott. The board agreed and Scott received the medal.

At various times in the Red Eagles’ history, the squadron worked closely with AFSC’s 6513th TS, Red Hats, and its test pilots at Edwards AFB to conduct testing that fell outside of CONSTANT PEG’s original remit. “The airplanes were used not only to validate tactics, but also to do initial tests,” Matheny explained.

Some 4477th TES commanders disliked such collaborative efforts, perhaps because they had little say in the matter and because the assets and their pilots were sometimes sequestered by Systems Command, but most probably because they took exposures away from the TAF – the frontline squadrons. However, these tests were usually of great value. Sometimes, AFSC wanted more, and “borrowed” assets from the 4477th TES when it needed them.

White recalled that Gen Fischer particularly disliked having to share the assets with the Red Hats. “He hated them with a passion. Several times, the only reason we did testing with them was because we were ordered to do it by HQ.” Whether Bond’s mishap had influenced Fischer’s view is not clear, but White said this:

He thought that they were unprofessional, that their facilities were shabby, and that they didn’t go by normal maintenance standards or practices. On one occasion they had asked for the use of one of our airplanes. The call had come to my home on a Saturday morning while Fischer was away on a cross-country trip in his F-15. I met with Gen Ashy and we agreed we’d meet him when he landed on Sunday. The next day, we met him after he put his gear away. Ashy told him what had happened. Fischer jumped out of his chair and almost screamed, “Not only no! But, Hell no!” and stormed out. Ashy looked at his chest and then looked at mine and said, “I didn’t even feel that bullet go through.”

The relationship between the 4477th TES and the 6513th TS did sometimes have benefits, and several Red Eagle pilots over the years flew Soviet MiGs and Sukhoi jet fighters and fighter-bombers belonging to AFSC that the Red Eagles did not have. Some of these were completely new types, and others were more advanced versions of the MiG-21 and MiG-23 operated at Tonopah. Such brief exposures gave the Red Eagles pilots an appreciation of what they needed to be teaching the frontline fighter pilot about more modern and capable threats, or illuminated the subtle changes between one marque of aircraft and another.

The Red Eagles occasionally flew against TAC’s 422nd TES, “The Four-Two-Two,” which was based at Nellis and developed tactics and procedures that would accompany the introduction to service of a new aircraft, weapons system, radar upgrade, or capability. Some of these tests brought the technical exploitation of the MiGs full circle. For example, HAVE GARDEN, an earlier program to profile the MiG-21’s compressor and turbine blades, resulted in several US radars having their electronic identification (EID) libraries updated. These new updates were given their operational testing by the 422nd at Nellis, and to do so, the 422nd needed to fly against the actual MiG-21. The Red Eagles were therefore asked to help. The same process occurred with the Flogger. “The Tumansky R-29-300 in the MiG-23 would show up on our radars as a DC-10 because the compressor face was just so huge,” said Matheny. He flew the MiG-23 against 422nd TES F-15s equipped with the latest radar modifications to ensure that the new computer algorithms could correctly identify the radar returns as being those of an R-29A, as opposed to the General Electric CF-6 engines of the commercial airliner.

Matheny also worked with the Nellis squadron to conduct AIM-9L and AIM-9M testing against the MiGs’ engines. He flew his MiG in front of a fighter armed with a captive Sidewinder: “We wanted to see at what ranges, and under what conditions, the newer missiles could actually see the MiGs. ‘Can you see me here at this range, this throttle position? If I go to idle here, can you see me?’ That kind of stuff.”

Although the Red Eagles never fired live missiles, some former pilots recall that they did carry inert AA-2 Atolls. Dating from the 1960s, the Atoll worked just like the Sidewinder in that it looked for the hot exhaust of an engine, emanating a warbling tone in the pilot’s headset that varied in pitch according to how well its IR seeker head was locked on. When the tone reached a high-pitched shriek, the missile’s seeker had achieved a lock-on and the missile could be launched at will.

The AA-2 was less sophisticated than the newest versions of the Sidewinder for which Matheny had provided a target, and was easily decoyed by flares dropped from an opponent, or even the sun or a heat source on the ground. Similarly, its seeker head needed to be positioned almost directly behind an opponent before it could lock on to the hot engine. By contrast, the newer Sidewinders had an “all aspect” capability – they could be fired from head-on or from the side, because their seekers were sensitive enough to track the aerodynamically heated skin of the target if its exhaust nozzle(s) was not in view. This imbalance was unfair on the Red Eagles, but it did represent the reality of America’s technical advantage over the Soviet Union. Later, old versions of the AIM-9 were carried to simulate the AA-2.

In one test in 1985, Matheny flew the MiG-21 against AFSC test pilots assigned to fly the F-16XL, an advanced version of the Air Force’s lightweight fighter competition winner featuring a highly swept cranked-arrow delta wing; and the concept demonstrator of what would become the F-15E Strike Eagle, a strike-fighter version of the air-to-air F-15 Eagle. At the time, the two were competing against each other for the Air Force’s Dual Role Fighter competition. “The F-16XL was being flown by test pilots from Edwards,” Matheny explained. “We briefed each other about our airplanes and they turned around to me and told me that they were going to be all over me – they had a roll rate of 800 degrees per second, which was the fastest rate in the inventory.” Up until then, the record had been held by the T-38, which could be coaxed into a roll of 720 degrees per second.

“I got to thinking about that and it turned out that the roll rate meant nothing,” he continued. “The problem with that airplane was that it was a big bleeder: it just bled airspeed like nothing else when it was forced to turn hard. I ate them alive in the MiG-21. The F-15 on the other hand flown by 422nd TES pilots was a pretty good performer – they resisted the urge to get slow and jump in a phone booth with the MiG. They flew all the way around the ranges at low level trying to burn off all this gas and he still needed to burn off more when we joined up on each other.”

In November, two new pilots joined the squadron. Capt Edward D. “Hog” Phelan, “Bandit 47,” and Navy lieutenant Guy A. Brubaker, “Bandit 48.” Phelan was a surfer and UCLA graduate and cheerleader who’d once interviewed for a sales position with IBM, but found the stuffy corporate image incongruent with his own. With a desire to drive either boats or aircraft, he looked to the Coast Guard first, but actually joined the Air Force when someone told him they wouldn’t make him get his hair cut short. Since he saw his hair as crucial to his ability to chase skirt, that was a major consideration.

Following pilot training in 1973, he went to Torejon AB, Spain, to fly the F-4. There he had met Bland, forming a friendship that ultimately resulted in his getting assigned to the Red Eagles. He had gone through the 414th FWS in 1981, and then been assigned to the F-4 RTU. “I was an IP, but my real task was to try and get the IP corps infused with some good air-to-air experience. As a Weapons School graduate, I was there to teach them some broader and deeper air-to-air skills.” It was far from an exciting assignment, and few of the IPs wanted to hear what he had to say.

By 1983, he was interviewing at Nellis for a job at the 414th FWS. “The problem was that I had not been at the RTU for long enough, and they weren’t willing to flex. Luckily, I had met Dave Bland at the bar at Nellis, and he told me that he might be hiring. Part of the thinking was that the 4477th TES was too Nellis inbred – all the people were coming from Nellis – and the program was moving from being super-Top Secret to something less.” In order to join the Red Eagles, Phelan had first to go to the Air Force’s flight safety school, since Bland was recommending Phelan to Gennin on the basis that he would join the squadron as a trained safety officer.

Gennin had agreed, and Phelan was hired. But he almost never made it to the Red Eagles. Before he could fly the MiGs, the squadron sent him to get his Federal Aviation Authority (FAA) commercial multi-engine rating. “My 400-hour check pilot tried to kill me a couple of times. In fact, on my last check ride we ended up in storms and 80-knot winds. We were in this little Cherokee and there was so much turbulence that he turned the airplane around on the airways. I took control and got us home. When we landed, he kneeled down and kissed the ground. Then he hugged me and thanked me for saving his life.” Next he got rated in the T-38, and finally he started transitioning to the MiG-21. The whole process took around one month.

In the fall of 1984 Gail Peck, the Red Eagles’ creator and now a colonel, would once again be briefed into the program. His dismissal by Kelley all those years before had seen him “read out” of CONSTANT PEG, resulting in his being totally in the dark about its progress. Fortunately, his career had not been ruined, and he’d been promoted to colonel and assigned the position of vice wing commander of the 18th TFW, the F-15 Eagle Wing based at Kadena AB, Japan. Peck had deployed six jets to Nellis to fly against CONSTANT PEG, and himself flew a sortie against a MiG-23. With the deployment over, Peck was once again read out of CONSTANT PEG.

Between November 26 and 30, the 4477th TES was the focus of a Local Management Effectiveness Inspection (MEI) that had been directed by 57th FWW Deputy Commander, Tactics & Test, to prepare the Red Eagles for an upcoming TAC MEI. This MEI was yet another sign that the Red Eagles were being treated increasingly like other TAF units.

While the 4477th TES had its fair share of brash, loud, outspoken, and eccentric personalities, few could match the quirky nature of one particular technical sergeant known universally as “Weird Harold.” Harold’s eccentricity wasn’t universally appreciated – particularly not at the squadron commander level – but most thought him particularly entertaining. Harold was an ex-Thunderbirds maintainer who hailed from one of the southern states, and with whom Fisher had briefly shared a trailer at Indian Village – “He used to bring back moonshine,” he recalled approvingly. Bucko recalled that Harold would often work the ramp area – serving the MiGs and preparing them for flight – wearing a dress. He sometimes waved the MiGs out from the ramp with nothing on other than his belt and radio.

For Gennin, who had been unaware of who and what Harold was, his first meeting went down like a lead balloon. As the new Red Eagles commander sat at the bar in the Indian Village, Harold, wearing red lipstick, a blonde wig, and a flowery dress, pulled up a chair next to his new boss and introduced himself. Gennin, bystanders said, was not amused.

For new pilots, said Matheny, Harold reserved a vile but equally hilarious trick known as his “baby chicken in a box.” He would excitedly invite the pilot to rummage through the straw to see his baby chicken. The poor victim would put his hand in the box to pull back the straw, only to discover Harold’s genitalia stuffed through a hole in at the side. Shervanick recalled that Harold would also occasionally wear a rubber chicken on his head. “He was like the character Corporal Klinger out of TV show, MASH, but I tell you what, he could fix an airplane.”

Geisler was present one day when US Navy admiral Tom Cassidy, of HAVE DOUGHNUT fame, arrived in an F-5E for a VIP visit. “Hound Dog was stood at the ramp as the admiral shut down. From behind him, Harold ran out to the jet. He had his combat boots, a web belt, and a hat on. Nothing else. He ran up to the airplane, climbed up the ladder and kissed the admiral on the cheek. Then he runs back into the hangar! Phil just does not know what to do. We all knew that Weird Harold and Admiral Cassidy were good friends, but Phil did not.”

While Harold may not have left Gennin with the sort of enduring impression from a first meeting that most people would have aimed for, since Ellis’ departure Harold (whose experience probably went back as far as DOUGHNUT) had stepped up to the plate as one of the most senior maintainers and his colleagues and superiors respected him. Geisler was one of them:

Gennin knew how the maintenance guys respected Harold. He walked a fine line and treated Harold with a degree of respect. I personally think Gennin was able to somewhat “win” Harold over, and that was one reason maintenance got on board with the changes he introduced. In turn, they became the best bunch of professional maintainers in the military. Harold never wanted anyone to get hurt and was very protective of “his” pilots and MiGs. Gennin and Weird had professional respect for each other. Never did I ever see or hear Gennin say anything negative to or about him.

However, Gennin told me that he eventually ordered Tittle to have him reassigned.

There were also well-established pranks and traditions that the pilots would play on one another. One of them was called “Firsts,” where a new pilot was told that the first time he did anything in the squadron he had to pay a fee to the bar fund. “If it was your first taxi, you paid $10. Your first take-off, $20. Your first landing, another $20, and so on,” Matheny chuckled. “Some guys you could get $200 or $300 out of, and then of course you’d go and buy something for the squadron and show it to the guy, telling him, ‘Hey! You bought this for us!’” Time and again the same name came up as the main protagonist behind many of the other pranks that characterized the lighter side of life at Tonopah in the 1980s: Geisler.

Geisler was the genius behind what became known as the “Boom Recovery.” Initially it began because it was a useful bargaining tool, but later it seemed to be little more than a sport. He confirmed that it had all started when he had been talking to the F-117 pilots at the Man Camp:

I asked them if we were keeping them awake during the day. They told me, “Hell, no, it’d take more than that to disturb our sleep.” “Really?” I said. The next day I briefed the new Boom Recovery to all the guys: “These fuckers don’t think that we can keep them awake. Save enough gas to descend from 30,000ft as fast as you can. Point directly at the Man Camp and make sure you’re at 5,000ft when you pass over it supersonic – make it brutal! Then fly up the initial [the approach to the runway] and land.” We ended up booming them so bad that the hangars were shaking, pictures were falling off the walls, and we were even scaring the crap out of our own guys! Then the phone rang – the -117 guys said, “OK, we give up!” Those booms were scary and we had flattened that Man Camp!

Some of the booms to which the Red Eagles subjected the F-117 pilots and maintainers were far more innocent. In winter time particularly, the MiGs performed better in the cold Tonopah air, their jet engines deriving an additional performance boost the colder it became. This was not lost on Stucky one day who, having recently converted to the Flogger under the guidance of Saxman, was giving a pair of F-14s a PP:

We did an acceleration profile, where I was going to show him how fast we could go. 860 knots was the red line on the Flogger’s airspeed, so we would go right up to that speed. We were flying over the “Dog Bone” lake near Tonopah at about 0900. We ran up the Dog Bone and boomed the whole [TTR] complex because there were three of us. The commander of the other unit [4450th TG] was Col Mike Short, who I had flown F-4s with. He was having a staff meeting at the time and a bunch of his ceiling tiles had come loose and dropped onto his table.

Short was not amused.

“Sometimes the supersonic shockwave would actually move hangar doors,” Drake commented. “And if the styrofoam ceiling tiles did not actually fall out, they’d be shaken so much that this layer of ‘snow’ would sit there on the desks and floors.”

Stucky and Geisler were soon operating as partners in crime, and their friends and fellow pilots learned quickly that neither man could be trusted when jokes were concerned. All of the Red Eagles were given a security badge that could only be worn at Tonopah and without which they could not disembark the MU-2. If they were already at TTR when they lost it, they would be detained until the squadron commander walked into the security police building and verified they were who they said they were. The badge policy offered Geisler and Stucky all sorts of opportunities for mischief. “You could bump into a new guy in the hallway and take his badge off of him without him noticing,” Geisler admitted. “You immediately went to the pisser and taped it inside the urinal. Then you’d go to the maintenance guys and tell them that so and so’s badge was there, and they would line up to piss on it. Then we would announce on the loudspeaker that the pass had been found and was available to collect from the men’s room.”

One variation of the game included stealing a pilot’s pass as he slept during the journey from Nellis to TTR in the MU-2. The Red Eagle’s Marine at that time, Tullos, often fell foul of this trick, Geisler exclaimed. “He would never learn, and he always fell asleep. While he slept, we stole his pass. The cops would arrest him as he got off the plane, and we’d look over our shoulder and say, ‘It’s OK, I’ll fly your hops today, Cajun!’”

When they grew bored of this, Stucky confessed, they concocted an even crueler trick. “We took Cajun’s briefcase, changed the combination to the locks, and then put his pass inside it. We all get off the airplane but George won’t because he knows he is in big trouble if he steps off without his pass. It was like the Samsonite suitcase commercial, where this big gorilla is trying to get into the suitcase. We were calling, ‘Hey! Cajun! Come on, let’s go!’ Eventually, Cajun just threw the briefcase out of the airplane to the surprise of the cops. We opened it for him, but he was just beside himself.”

Geisler’s sense of humor sometimes got him into trouble with his commanders, particularly when it was for the benefit of the Russian satellites. Tonopah was a magnet for satellite interest as it was, with each exposure lasting in the order of 22 minutes. “I once had the maintenance guys go up and paint ‘moya zopa’ – ‘kiss my ass’ in Russian – on the top of one of the hangars. On another occasion, I had them put a T-38 nose out of the front of a hangar, and an F-5’s tail out of the back, so that from the air it looked like we had an airplane about 108ft long. In the end, it actually attracted more satellite attention, so the commander told me to quit doing shit like that.”

Geisler explained more about Soviet intelligence efforts: “We knew that they [the Soviets] knew [about the MiGs], but we knew that they didn’t know how many, how often we flew them, or to what degree we were using them for – they had no idea how many pilots we were training against them.” He added: “At around that time, some Soviet general officers and other dignitaries came to Nellis on a ‘be good to each other’ tour. Myself, the squadron commander, and some Aggressors were having dinner with them and everyone was being cordial. Then, one of these Soviet Air Force generals interrupted one of our generals mid speech: ‘So, General, how many MiGs do you have at Tonopah?’ Without batting an eye, he turned around and said, ‘I don’t know. Maybe 300, or 350?’ and then went back to his conversation. It didn’t phase him a bit. The Russian guy almost passed out.”

At the end of 1984, the 4477th TES had 15 MiG-21s and nine MiG-23s on strength. While this represented a total of nine more aircraft than they had at the close of 1983, the most significant statistic was that CONSTANT PEG had flown 901 sorties more than they had the year before. This improvement was largely down to Gennin. When Nathman had joined CONSTANT PEG in April 1982, one of his initial observations had been that some of the pilots thought of themselves as being just a little too exclusive. ‘The mission was to expose Air Force, Marine, and Navy guys to the MiGs, but it seemed like sometimes the Air Force would find any excuse not to fly. We actually started calling it Constant Keg because that was how it felt.”

But as Nathman departed Tonopah for the last time, it was clear that the CONSTANT PEG’s operational footprint had deepened and widened significantly in the two years he had been there:

One of the things that Gennin did was to focus the squadron back on its mission – he made it act and breath like an operational squadron. The Air Force was paying a lot of money, and there was a lot of talent. What we were seeing was us getting away from thinking that we were some kind of demigod out there in the desert, some sort of niche; and let’s really start getting our product out there: the exposure. In my first year, we didn’t fly that much, but by the time I was into my last year, we were flying our butts off. What I was most proud of, though, was that the experience – the exposure – had improved qualitatively, too.

The improvement in exposures is a fact evidenced, at least statistically, by the ratio of sorties to exposures in 1984: 2,099 sorties for 800 exposures, or 2.6 exposures per Blue Air pilot. In 1983, that figure stood at only 1.8 exposures per Blue Air pilot (1,198 sorties for 666 exposures). “Gennin had delivered exactly what the Air Force had asked of him,” Nathman applauded.