_______________________

_______________________

Bonded by success: Harry Saltzman (right), Ian Fleming and Cubby Broccoli pose for a photo after signing their agreement to produce the first James Bond film in 1962.

BOND ON BEGINNINGS

As I write I am sitting in Monte Carlo with my wife Kristina. The sweltering sun is beating down upon us as we sip our early-morning coffee, slip on our dark glasses and watch the millionaires – and billionaires – passing by in their designer clothes, their fast cars and on their yachts, while their luscious lady friends, all potential Bond girls, are busy sunning themselves on the terraces at the Monte Carlo Beach Club. It is a very ‘Bondian’ setting in which to write a book, though I feel I should start by confessing it wasn’t until 1962 that I first heard mention of James Bond – some eight or nine years after Ian Fleming had started writing his hugely popular books – but they, and he, had somehow passed me by.

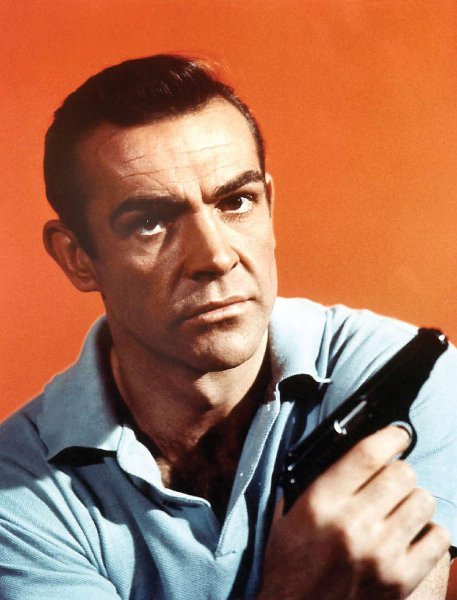

The birth of an icon: a very early publicity shot of Sean Connery as 007.

WILL HE, WON’T HE?

Following a spell in Hollywood, where two studio contracts were swiftly followed by a plane ticket home, in 1960 I wound up in Rome, making a couple of what you might call ‘miracle-movies’. That is to say, it was a miracle if anyone got to see them.

My agent, Dennis Van Thal, called while I was in Venice gorging my face on a favourite dish of black pasta, flavoured with a little garlic, shallots and with a decent handful of prosciutto, all complemented by a glass of Pinot Grigio on the terrace of the Gritti Palace Hotel, which itself sits on the banks of the picturesque Grand Canal. Very Flemingesque, eh?

Dennis had received an offer from British television mogul Lew Grade for me to play Simon Templar in a television series of The Saint. I was immediately and greatly interested because I knew those books and had, in fact, at one point made an – unsuccessful – approach to their author, Leslie Charteris, to buy the rights.

To cut a long story short, I accepted the contract and found myself back in England with a regular salary jingling away in my pocket.

A little financial security is always a good thing for an insecure actor, and with it I soon began behaving in a Bond-like fashion by visiting the tables of the gaming houses in London’s Curzon Street. It was there I first met two larger-than-life, and obviously affluent, American gentlemen who introduced themselves as producers Harry Saltzman (a Canadian) and Cubby Broccoli (an American of Italian descent). Over the ensuing months we exchanged a fair amount of casino money across the table, but moreover developed a close friendship, which lasted the rest of their lives.

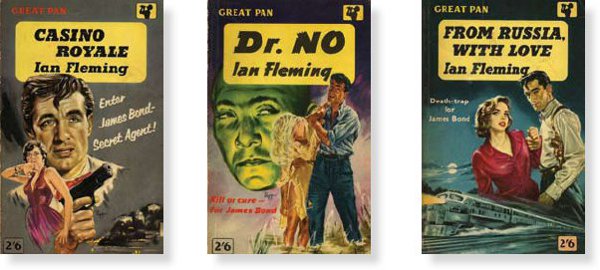

It had to start somewhere! A few covers of Ian Fleming’s books, which I’m assured all sell for more than 2 shillings and 6 pence these days. Interesting that I’m on the cover of Dr. No – even though a well known Scottish actor was in the film.

They were then just setting out on producing a series of films about ‘James Bond’. That was the very first time I’d heard the name. Cubby and Harry told me about agent 007 and invited me to the first screening of Dr. No and, later, all the other Sean Connery Bond films, at their Mayfair headquarters, Eon Productions in South Audley Street. I was greatly enlightened, entertained and captivated by the good Commander and his amazing exploits.

I was big in Birmingham. A ticket stub for a first-night screening.

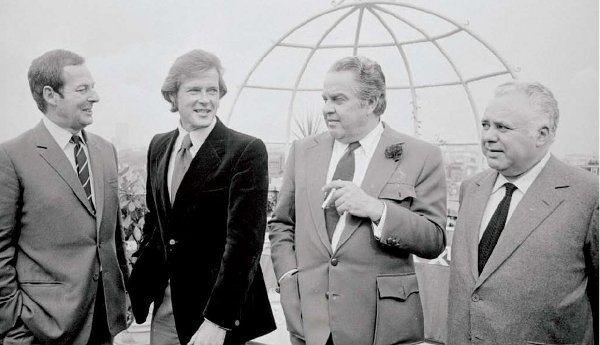

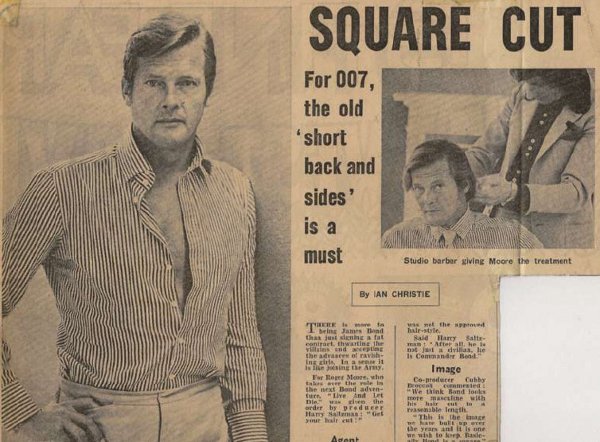

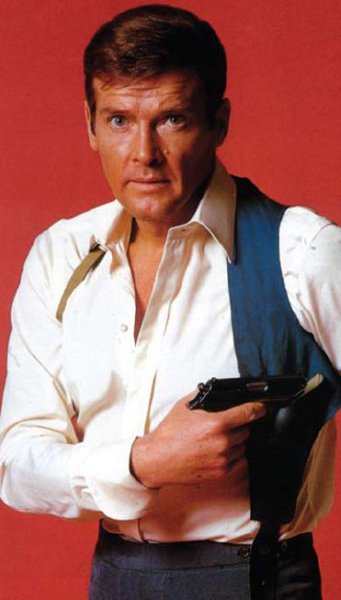

Photocall on the roof of London’s Dorchester Hotel, announcing me as the new James Bond with director Guy Hamilton on the left, Cubby Broccoli in the middle and Harry Saltzman on the right. Note how Harry’s looking at my hair, wondering how many inches I should lose.

The Saint, meanwhile, happily ran and ran. In fact I clocked up 118 episodes over seven years. It was towards the end of the penultimate series in 1967–8 that the idea of me playing Jimmy Bond was first mooted. Sean Connery had completed You Only Live Twice and stated that it was to be his last. Keen to keep the franchise afloat, the producers started thinking about recasting. They must have heard I worked cheap.

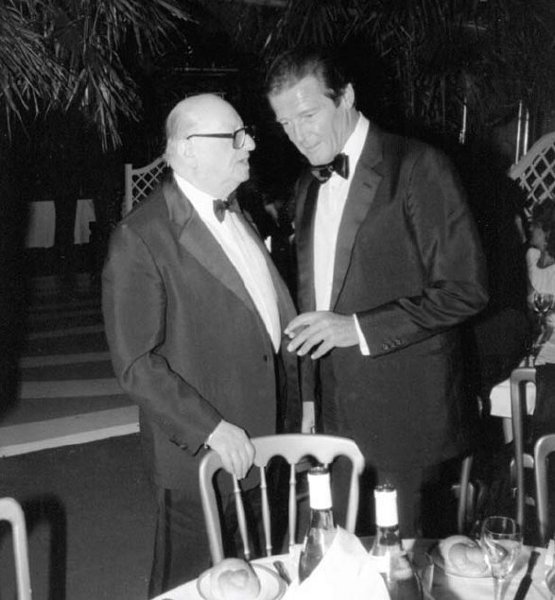

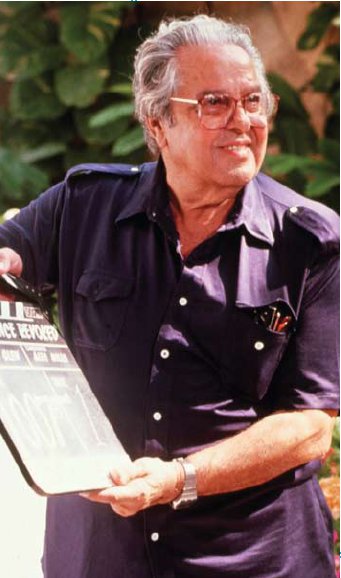

With my dear friend Lew Grade, who told me that playing Bond would ruin my career.

Producer Harry Saltzman called. ‘Let’s talk about you doing Bond.’

Producers, writers and agents’ discussions commenced around an adventure set in Cambodia. Unfortunately, very soon afterwards all hell broke loose in that country and the production was shelved. With uncertainty about what might happen, and with the prospect of another – financially appealing – series of The Saint looming, I returned to film what would be my last season of the show.

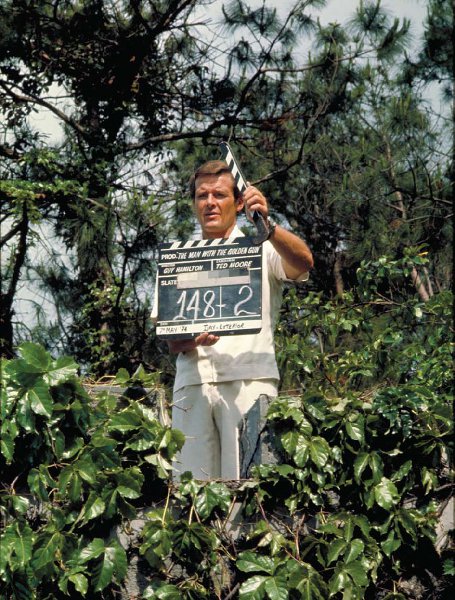

I was expected to do everything! On location for The Man With The Golden Gun.

Keen to get back into movies, I simultaneously began developing a couple of projects with my Saint producing partner Bob Baker, one of which – Crossplot – we filmed with funding from United Artists, the backers of the Bond movies. I then became an actor-for-hire in The Man Who Haunted Himself for Bryan Forbes at EMI, before teaming up with Bob Baker again to star in, occasionally direct, and produce a TV series called The Persuaders!. Oh, and thanks to my friendship with Cary Grant I also took up an executive position at Brut Films to oversee a few rather successful productions, including the Oscar-winning A Touch Of Class.

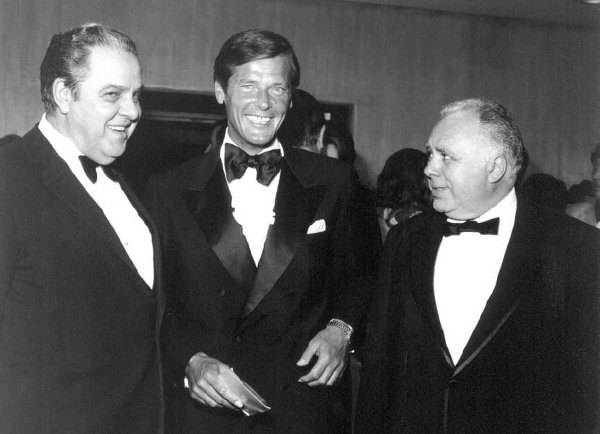

Here I am at the premiere of Live And Let Die with my benevolent producers.

Life was pretty good, and very busy. Cubby and Harry were busy doing their thing too, and while we stayed in touch, when they regrouped I became ‘unavailable’ due to my own filming commitments, and so they made Jimmy Bond an Australian, albeit for one adventure only.

Only after Sean returned for – and said ‘never again’ following – Diamonds Are Forever, in 1971, was I brought back into the frame and, happily, I was between acting gigs.

‘Are you alone?’ Harry asked when he called me long distance at my Denham home (my phone number, oddly enough, was Denham 2007). ‘You mustn’t talk about this,’ he added, ‘but Cubby agrees with my thinking in terms of you for the next Bond.’

I didn’t say anything to anyone. Once bitten, twice shy.

Contracts were drawn up and duly signed. It was a few weeks before Harry called again, to say he and Cubby felt I was ‘too fat’ and my hair was ‘too long’. I said I’d get a haircut and take the weight off.

I told my dear friend Lew Grade (who along with The Saint also bankrolled The Persuaders!) that I was to be the next 007. With tears welling in his eyes, he shook his head and said, ‘Roger, don’t do it. It’ll ruin your career!’

‘What career?’ I hear you say.

There is always a huge challenge associated with taking over a role from another actor, particularly when he has enjoyed great success in said role. I knew I’d face comparisons and wondered if I’d even be accepted by audiences. However, I consoled myself by thinking about the hundreds of actors who have all played Hamlet. Besides, if it didn’t work out I could always go back to modelling sweaters and gorging myself on more Flemingesque lunches in Venice, while letting my hair grow down my back.

It’s not every day my getting a haircut made the newspapers.

FINDING THE KEY

At the outset, I knew I would have to be tougher than the other screen heroes I had played: Beau Maverick, Ivanhoe, Simon Templar and Brett Sinclair. However, having known many soldiers and servicemen, I didn’t necessarily believe that Bond was a man who enjoyed killing. He’d have to be rather sadistic to get a kick out of it. In fact, when I re-read the Fleming novels there was a line that stated, ‘Bond did not particularly enjoy killing’. And that was the key to my interpretation of the role: I wouldn’t enjoy killing, but I’d do it professionally, quickly and accurately.

What else? Well, Fleming made it clear Bond enjoyed the finer things in life from food, drink, cars and travel to, ahem, women. That’s not a bad job description, is it?

But what of Bond the man? Ian Fleming gave very little away about the character until he penned an obituary for Bond. Had the author not been persuaded otherwise by his publisher, the obituary would have come a lot sooner than it actually did. After just four books, feeling he’d done his duty and his adventures had run their course, Fleming grew tired of his hero, much as Arthur Conan Doyle had done with Sherlock Holmes. He fully intended to have Bond murdered at the end of From Russia With Love. Thankfully, he was talked out of it and continued the series. The memorial piece was reserved until You Only Live Twice was published (six novels later) – and was written by 007’s boss, M.

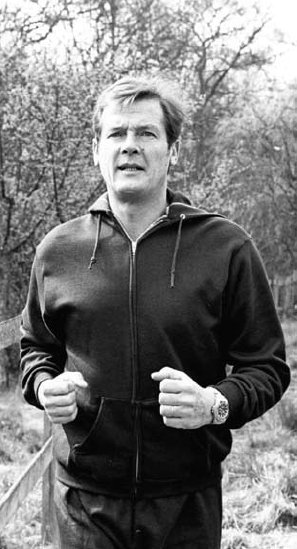

Having lost some hair, I was now trying to get fit and lose some weight – at my family home in Denham.

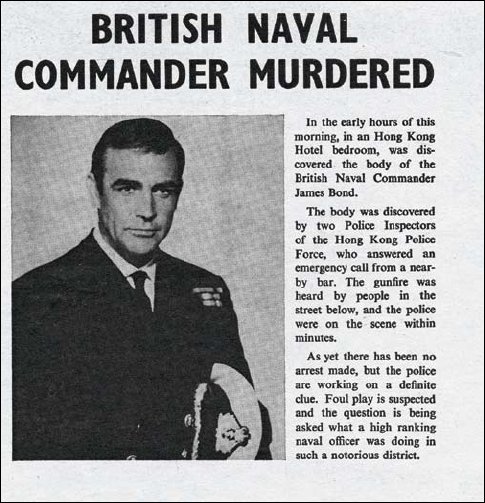

‘Commander James Bond, CMG, RNVR,’ it started, referring to Bond’s naval service and his being a Companion in the Order of St Michael and St George, ‘was born to Andrew Bond, of Glencoe, Scotland, and Monique Delacroix, from the Canton de Vaud, in south west Switzerland.’

Andrew Bond was a foreign representative of the Vickers armaments firm, and Jimmy travelled with his parents wherever their work took them. When Jimmy was but a mere eleven years of age, both parents were killed in a climbing accident in the Aiguilles Rouges, France.

Jimmy was an orphan. Poor Jimmy.

Bond’s early education was undertaken abroad and so he became fluent in both French and German. After his parents’ deaths, young Jim went to live with his aunt, Miss Charmian Bond, in Pett Bottom, a hamlet near Canterbury, Kent.

Then, Fleming revealed, aged twelve our young hero was entered at Eton College, but after a year there was ‘some alleged trouble with one of the boys’ maids’ and he was transferred to Fettes College in Edinburgh, where he took part in wrestling, founded a judo class and graduated early at the age of seventeen.

As for me, at seventeen I’d left school, been fired from my first job (not through problems with any maids, I might add) and was wondering what I would do with my future. Unlike Jimmy, I was not recruited by the special branch of the Royal Navy Volunteer Reserve, nor, a few years later, was I approached by MI6.

Bond’s demise was reported in You Only Live Twice on the front page of a newspaper.

Thankfully, the obituary was a ruse to put off Jimmy’s pursuers. He wasn’t dead, but it proved a helpful ploy in the adventure. It also proved helpful to us readers in stitching together a backcloth to the character. I’ve never been guilty of method acting – or even acting, if you want to argue a point – but doing this bit of background reading in You Only Live Twice gave me a few ideas about the character and why he was who he was. But throughout I kept thinking about that line ‘James Bond did not particularly enjoy killing’. That was the key.

THE BOND PHENOMENON

Sean Connery had enjoyed huge success as the first filmic Bond. When Dr. No first hit the screens in 1962, in my humble opinion, where leading heroic parts were concerned, Sean changed everything. The world of Bond blew a hurricane breath of fresh air into the adventure-movie genre with its larger-than-life villains, even more evil than Satan himself; drop-dead-gorgeous girls who in fact did often drop dead if they found their way to Bond’s bed in the first half-hour of the film; hugely glamorous locations and sets; and a hero who was impeccably turned out, with the best taste in everything and the enviable ability to disrobe a leading lady in the flick of a camera shutter.

In an era when travel was the reserve of the rich, post-war rationing and rebuilding was still a vivid memory, and fine living consisted of a night out at the pictures followed by a fish-and-chip supper, James Bond offered something exciting – something previously unimaginable. Bond swiftly became a phenomenon.

But, as with all success stories, it very nearly wasn’t.

Harry Saltzman had an option on the books, which was fast running out. Columbia Pictures had turned it down, as had other potential backers. It was through partnering with Cubby Broccoli, and Cubby’s friendship with Arthur Krim at United Artists, that the series was eventually launched.

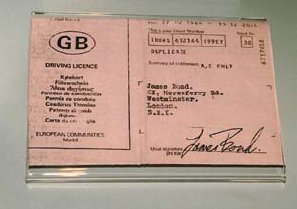

Although relatively few details are known about Jimmy’s home life, he did have a driving licence for one of the films. Westminster? Hmmm. I thought he lived in Chelsea.

A deal was struck with Krim and the fact that Cubby was able to loan Harry the airfare to get to New York and sign the deal saw the making not only of a great franchise, but also of a brilliant Scottish actor’s career, as well as fairly regular employment not only for Bonds but the villainous characters, glamorous girls, extras willing to fall off bridges and stuntmen keen to be hurled into the air by explosions and dive into shark-infested pools. The screenplay was co-written by Richard Maibaum, who went on to collaborate on twelve more of Jim’s adventures.

It is well documented that the first James Bond film was given a $1 million budget – and even for 1962, that was considered tight. Thankfully, it increased exponentially film by film, not least to accommodate my fee …The future of the franchise was very squarely dropped at my feet in 1972. I was to be the first English actor to play 007, and quite possibly the last if I ballsed it up.

THE SAME, BUT DIFFERENT …

So how do you follow someone as hugely popular as Sean? I hear you ask. Well, I was conscious I should at least not speak with a Scottish accent, and after discussions with director Guy Hamilton it was decided I would never order a vodka Martini, neither shaken nor stirred, nor would I drive an Aston Martin. They were too closely associated with Sean. I had to be the same, but different.

Of course, I watched Sean’s films again, and while not speaking directly with him about the part – after all, would I have called Larry Olivier and asked him about playing Hamlet had I been offered it? – being a friend of his I knew why he quit the role, and remember his declaring he’d ‘created a monster’. Sean wanted to distance himself from 007 and the associated hysteria and potential typecasting, to tackle other acting roles. I, on the other hand, was just grateful for a job.

Oh, and I should not forget George Lazenby, who had one shot at playing Jim in On Her Majesty’s Secret Service in 1969. By his own admission George was not an actor. He was a car salesman who began modelling and then slid sideways into acting work. His good looks and ability to throw a punch, coupled with his arrogance, secured him the part. I got to know him later on and, with hindsight, he admitted he had made a huge mistake in not signing on for seven movies, as originally offered, and parachuting out after just one on the advice of his friend-cum-manager Ronan O’Rahilly, who stated, ‘Bond is Connery’s gig. Make one and get out.’ The irony is, George is probably never going to be able to shake Bond off.

Ready for action in Live And Let Die, my first outing as Jimmy Bond.

My friend Peter Hunt directed On Her Majesty’s Secret Service and, while very pleased with how it turned out, did confide in me that he’d had many problems with his lead actor’s behaviour; presumably not helped by Harry Saltzman saying, ‘You are now a star, George. Behave like one.’ Stories became legendary of George sending back the studio car in the mornings because he didn’t like the colour, demanding a car to take him the fifty yards from his dressing room to the Pinewood restaurant, and of eating garlic ahead of a love scene.

As had become the tradition, Cubby and Harry invited me to Eon’s HQ in South Audley Street to watch the first screening of On Her Majesty’s Secret Service. I guess there were thirty or forty other people there, one being Bob Goldstein, who then headed up 20th Century Fox. He stood up at the end of the film, leaned over to Cubby and said in his gruff voice, ‘You should have killed him and saved the girl!’

In October 1972, I picked up my script, turned to page one and, heeding the advice of The Master, Noël Coward, prepared to ‘learn the lines and don’t bump into the furniture’. I guess I did something right, as, from then until we wrapped on my seventh Bond adventure thirteen years later, people went to see the films and kept me gainfully employed.

When I handed in my licence to kill I was constantly asked who should replace me. No! I lie. I was asked that question after about my third film, which, of course, gives an insecure actor a great feeling of being wanted. In fact, I did make a number of suggestions to Cubby – always names of really bad actors so I looked good by comparison. In the end, I was forced to abandon that idea as I couldn’t find any actors worse than me.

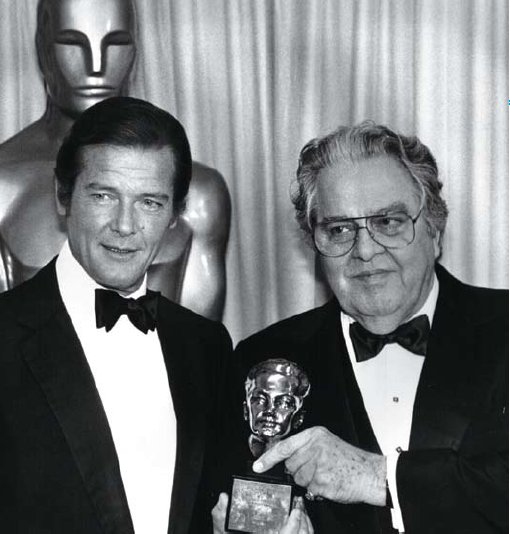

ALBERT R. ‘CUBBY’ BROCCOLI CBE

I could write a whole book on Cubby alone. He was a big man in both life and charm. A kind, caring and fun person, Cubby would always listen to ideas and suggestions from any member of the crew – he might not necessarily agree, but he listened – and that was a quality that endeared him to everyone. He was known universally as Cubby, from studio heads to the tea lady. There were no pretentions or nasty sides to Cubby. Sure, he could be tough in business, but his heart was a big one and his loyalty unswerving.

Cubby had read Ian Fleming’s books and thought they would make terrific films, but on enquiring about the rights discovered that a Canadian producer named Harry Saltzman had an option on them, which is how the duo got together in the first place. From there, a production company named Eon was formed, and the rest is history.

Cubby’s enthusiasm for Bond never diminished. He loved making the films, and took great pride in showing every dollar of the budget up on the big screen. But that was never enough for the press: they always asked Cubby if he ever wished he’d won an Oscar.

‘The only award I need is green with Washington’s head on it,’ he replied, referring, of course, to dollar bills at the box office. A successful movie was bigger than any trophy to Cubby. However, in 1982 the issue was addressed by the American Academy, when they bestowed their highest honour – the Irving G. Thalberg Award – on my friend. They asked me to present it to him on the night, and I remember Dana, his wonderful wife, looking rather worried that I might say something silly and fool around on this very prestigious night. Me? Would I?

After Octopussy, I resigned myself to thoughts of retirement. There are only so many stunts an ageing actor can tackle, and only so many young girls he can kiss without looking like a perverted grandfather. However, I was persuaded back by Cubby for A View To A Kill. A year later and with rumours of a new Bond script being finalized, I decided I really couldn’t go on to an eighth. I sat down with Cubby, who had obviously had similar thoughts, and it really became a mutual decision over lunch that I would step down. There were no tantrums, no attempted negotiations. It was all extremely amicable.

My friendship with Cubby outlived my time as Bond, and he told me of his thoughts of casting Pierce Brosnan in the role of 007. I said it was a terrific idea, as Pierce was an actor not unlike myself in style and looks. When that didn’t quite work out because of contractual complications, Cubby told me he was signing Timothy Dalton for three films, and I wished them both great success.

The next time I met up with Pierce and Timothy was in 1995, at the memorial service for Cubby at London’s Odeon Leicester Square. When I last saw him in California we laughed and joked about the times we’d shared, but, alas, Cubby was suffering ill health and was never able to return to the set of a Bond film, which I know he so looked forward to doing. I miss him greatly.