INTRODUCTION.

L

IKE

Mary Shelley’s Frankenstein

almost seventy years earlier, The Strange Case of Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde

came into being in the fall of 1885 thanks to a nightmare. Robert Louis Stevenson, upon being woken from this unsettling dream by his wife, Fanny, who’d responded to his pitiful cries, complained that she’d roused him out of “a fine bogey tale.”

Ever an unwell and often bedridden man, Stevenson spent the next three days locked in his sickroom, feverishly writing and crafting his vision into a story. Finished with his first draft, he came down and read the story to Fanny and her seventeen-year-old son, Lloyd Osbourne, to get their reaction. Though the youthful Lloyd loved it, Fanny’s response was muted, until she had to admit she thought he’d missed the point altogether. He “had missed the allegory,” she informed him, “had made it merely a story…when it should have been a masterpiece.”

Stevenson, at first incensed at her frank dismissal of his work, retreated to his sickroom in silence. Finally, he returned to concede that she was right and then threw the entire handwritten draft of his novella into the fire—ensuring that he would start over from scratch rather than be tempted to simply rework the deficient manuscript. In less than a week, again toiling away on his creation from his sick bed at Skerryvore (their Bournemouth home in the south of England), he completed a new draft that would become, with more revising over the next several weeks, the classic story we know—or at least know of—today. Released first in the U.S. on January 5, 1886, by Scribner’s for one dollar, the short novel appeared on January 9 in the UK from Longmans, Green, and Co. for a shilling.

Aided by a positive review in the Times

of London, The Strange Case of Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde

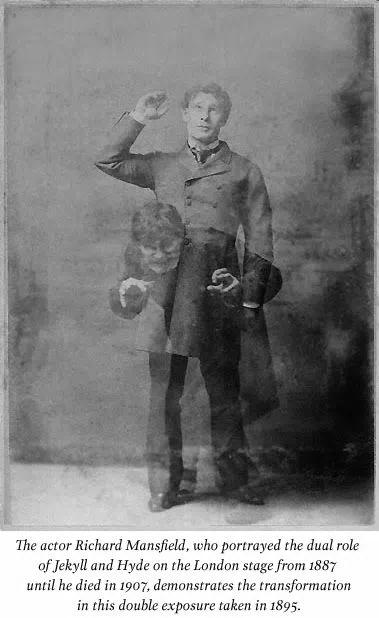

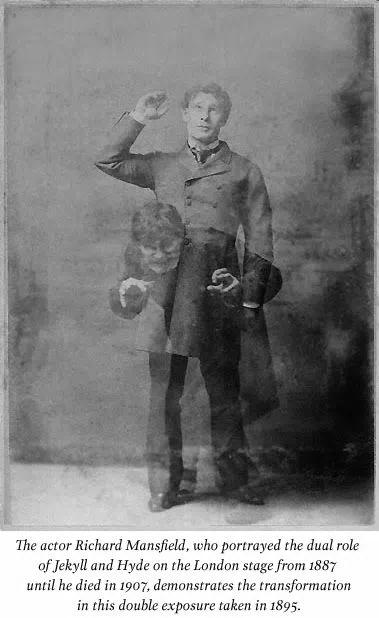

met with immediate success both at home and abroad, making the thirty-five-year-old author of Treasure Island

independently wealthy for the first time in his life. Within a year, the book had inspired theatrical adaptations in Boston and London, and soon across England and Stevenson’s native Scotland. It’s gone on, of course, to countless stage, screen, radio, and TV adaptations, including the inevitable Broadway musical version (which ran from 1997 to 2001 and was revived in 2013).

And it’s the adaptations—as opposed to the original novel—from which most people doubtlessly derive their impressions of Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde

. The revelation of Stevenson’s original text is how distinct it remains from its progeny. The book really doesn’t fit neatly into any one category—it works as part mystery, part gothic horror story, part science fiction, and part morality tale. Likewise, its narrative structure is unusual—and unusually effective, as it builds from seemingly mundane circumstances to a crescendo in the final act in which Jekyll reveals the horrifying and pitiable truth of his predicament.

Returning to a comparison between it and that other, earlier, nineteenth-century mad scientist/gothic horror story, it’s difficult not to note one significant—and instructive—difference: unlike Shelley’s Dr. Frankenstein, Stevenson’s Dr. Jekyll doesn’t create his monster; he unleashes it, setting it free from his own inhibitions, propriety, and morality. Jekyll always conceals Hyde within himself, even once he sets him loose, yet Hyde seems to possess little, if any, of Jekyll’s restraint or nobler traits. Since his youth, Jekyll has harbored darker desires—and at times acted on them—but always with the knowledge that they were wrong, not to mention unseemly for a man in his position. The truly diabolical thing about Jekyll’s “creation” is that he didn’t separate his baser, animal alter ego from himself in order to destroy it, he did it so that he could enjoy the life of a dedicated reprobate without soiling his own spotless reputation or feeling the pangs of conscience to which Victorian gentlemen of a certain standing were subject. Where Dr. Frankenstein was a fanatical idealist, Dr. Jekyll is a hypocrite, a repressed outlaw, incapable, even once he knows the evil to which Hyde is destined, of refraining from sliding back into the ill-fitting cloak of his stunted, bestial self.

And what are Hyde’s sins? What is it that Hyde gets up to late at night in the seedier streets of Soho in late-nineteenth-century London, to which an abashed Jekyll finds himself so inextricably drawn? We never really know for sure, as Stevenson leaves that up to our imaginations. If later adaptations are any guide, one imagines whoring, drinking, fighting, whoring, gambling, stealing, and…whoring. The libidinal aspects of Mr. Hyde are barely hinted at by the author, but—from the first theatrical adaptation to the most recent and every one in between—good God, has everybody else made sure to emphasize that.

Some subtexts are just too obvious to miss.

The obvious takeaway, hidden though it may be, is far from the dominant theme in Stevenson’s text, which tends to focus on Hyde’s cruelty more than any other downfall. The allegory that his wife Fanny envisioned became, in the author’s hands, a complex fable deconstructing the all-too-human struggle between good and evil and the gray area in between. In a pivotal moment for Dr. Jekyll, while sitting in the sun on a bench in Regent’s Park, “the animal within me licking the chops of memory,” he succumbs to the gratification of savoring his misdeeds as Hyde and is lost. Once and for all gone—his doctor’s compounds permanently irretrievable—neither science nor faith will be able to bring him back.

All we can do is reflect on Hyde’s desperate struggle to recapture the “father” he disowned and ponder the final act of the belatedly repentant sinner.

Alex Lubertozzi

Copublisher