“I longed to grow up to be the best butcher in the world,” Gertrude Behmenburg said about herself in 1943. Instead the four-year-old grew up to be Wilhelmina, America’s greatest model of the 1960s. She might have been happier—and lived longer—had she kept to her original dream.

When she died of cancer in March 1980, Wilhelmina was remembered as a great success—the last star of the couture era in modeling, the top moneymaking face of her time. She’d appeared on 255 magazine covers, including a record 28 covers of American Vogue. And in her second career as co-owner and president of Wilhelmina Models, she’d won one last magazine cover four months before she died; her photo illustrated an article about the rancorous competition that had made modeling, Fortune said, “more lucrative than at any time in its history.”

In her ten years of posing and a baker’s dozen more years as an agency head, Wilhelmina saw her trade change from a polite cottage industry filled with ladylike creatures who looked as if they never went to the bathroom to a $50-million-a-year business seething with enmity and greed and—apparently, at least—running on a current of money, drugs, and promiscuous sex.

Wilhelmina changed, too. She started out a willful beauty, master of herself and her course in life. But she ended up a secret victim, known as the head of the world’s second-largest model agency; a caring mother to models who could always come to her for advice; and a pacesetter who promoted blacks in the face of her industry’s indifference and racism—not as the battered wife of an abusive alcoholic; a mother who couldn’t protect her own children; a picture of superficial perfection whose daughter believes she chose to kill herself with cigarettes instead of facing, and fixing, her horribly imperfect life.

Wilhelmina was born in May 1939 in Culemborg, Holland, the daughter of a German butcher and a Dutch seamstress. Growing up in Oldenburg, Germany, she dreamed of a career as a nurse, a teacher, or an international spy. But on V-E Day she and her four-year-old brother were skipping down the street to get their day’s allotment of food rations when a group of drunken Canadian soldiers passed by, shooting their pistols in wild celebration. One of their bullets killed Wilhelmina’s brother. She determined that day somehow to make up the loss to her grieving mother, Klasina.

“She lived her life for other people,” says her daughter, Melissa. “The only thing she ever did for herself was become a model.”

In 1954 Wilhelm Behmenburg moved his family to a one-and-a-half-room apartment on Chicago’s North Side, where he’d opened another butcher shop. Daughter Gertrude entered high school not knowing a word of English, but she picked it up quickly from television, a part-time job in a five-and-ten-cent store, and the fashion magazines that “became my favorite reading material,” she said. “I even went to secondhand stores to buy all the old issues…. I read them cover to cover, devouring every word and every picture of my new idols, the beautiful models who reached so glamorously from the pages—out to me.”

In 1956 she accompanied a friend to a modeling school for an interview. The friend was too short. Gertrude, on the other hand, was tall enough and had the looks: widely spaced, hypnotic eyes and a full, sensuous mouth. “My head began to spin,” she recalled. Promising to repay him from her five-and-dime earnings, she borrowed the tuition from her father for an intensive modeling course. That May Sabie Models Unlimited presented her with a certificate stating she’d completed its professional modeling course “in creditable manner.”

Now Gertrude Behmenburg no longer existed. Gertrude just wouldn’t do, Behmenburg was too long and awkward to remember, and her middle name, Wilhelmina, was too foreign. In her place stood Winnie Hart, model. In 1957 “Winnie” began her career at beauty pageants. She was named Miss Lincoln-wood Army Reserve Training Center on Armed Forces Day in May. In July she was off to Long Beach, California, to compete in the Miss Universe pageant. She had small modeling jobs, too, and she took an after-school job as a designer-secretary-house model with Scintilla, a local lingerie company, to augment her earnings.

Wilhelmina photographed in Valentino couture

Wilhelmina, photographer unknown, courtesy Melissa Cooper

In 1958, just before she graduated from high school, Winnie joined the Models Bureau, the first agency in Chicago. “I damn near fell off my chair when she walked in,” recalls her booker, Jovanna Papadakis. The chestnut-haired beauty was already fighting the weight problems that plagued her throughout her career. Her Models Bureau composite gives her height as five feet nine inches, her weight as 132 pounds, and her measurements as 37-24-36. “A hundred thirty-two?” Papadakis laughs. “I’ve got news for you: We lied even then.” Winnie weighed 159. Nonetheless, the agent thought she resembled Suzy Parker and immediately called Victor Skrebneski, then, as now, the king of Chicago fashion photography.

Skrebneski, who’d started working for the Marshall Field & Company department store in 1948, had just lost his favorite model and girlfriend Mary van Nuys to the greener pastures of New York (where she later met and married literary agent Irving “Swifty” Lazar). When Winnie arrived at his coach house studio, Skrebneski took her under his wing. He even taught her how to back-comb her hair. “We spent many hours on that,” he says.

In 1959 Winnie’s picture started appearing in Scintilla’s mail-order catalog, and sales boomed. Impressed, her boss sent her picture to the International Trade Show in Chicago, and she was named its Miss West Berlin. “I had to speak to the girls at the trade fair,” says Shirley Hamilton, then a booker at another Chicago agency, Patricia Stevens. She took Winnie downstairs to a coffee shop and told her to order whatever she wanted. “Enjoy it,” she said. “You’re not going to have anything like it until you lose thirty pounds.”

Hamilton asked her why she called herself Winnie, then declared, “From now on you will be Wilhelmina.” Within six months all her advisers believed she was ready to go to New York. Early in 1960 Hamilton called Eileen Ford and set up an appointment. Skrebneski accompanied her. Ford told her that she couldn’t be a model “with those hips” but that if she lost twenty pounds, she could go to Paris and try to start with Dorian Leigh. So Wilhelmina flew to Europe, “sort of saying to myself, as an excuse in case nothing happened, that I was visiting relatives,” she said. She ended up staying a year and working nearly every day. “I put her on a diet, and she lost a lot of weight, and everyone adored her,” Dorian remembers. “She said, ‘I want Eileen to eat crow.’”

Willie, as friends called her, soon got jobs in London and Germany (where her native language came in handy). She also took her first location trip, to Gardaja, Algeria, where she was to pose in the Sahara in clothes by the couturier Madame Grès. The resulting pictures earned Willie her very first cover, for L’Officiel magazine. In fall 1961 she returned to New York, moved into a small apartment on East Eighty-fourth Street, and “took the city by storm,” says Papadakis. Wilhelmina appeared on twenty-nine more covers and was booked weeks, even months, in advance. She paid off the mortgage on her parents’ house, bought them a car, and made plans to send them to Europe.

It was a great time to be a model. The five top agencies in New York (Ford, Plaza Five, Stewart, Frances Gill, and Paul Wagner) claimed to book $7.5 million annually for print work alone. Beginners earned $40 an hour; top models, $60, less 10 percent commission to the agents. Even a junior category model, like Colleen Corby, could earn $45,000 a year at seventeen. Television residuals were a new and as yet unenumerated factor. “Some of us were earning seven hundred dollars before ten A.M. on the morning shows,” says Gillis MacGil, who’d kept working after opening her Mannequin agency for runway and showroom models.

By 1964 Wilhelmina had “risen to the top of the heap of the 405 girls who work under contract to the city’s top five agencies,” the New York Journal-American reported in a series called “Private Lives of High Fashion Models.” Jerry Ford called her the outstanding model of the early 1960s. “Her look was the look of the time,” he said. Although she was to earn $100,000 a year, she was plagued with insecurity. “It’s hard enough to become a successful model,” Wilhelmina said later. “But it’s twice as hard to stay successful. You can be out so fast if you don’t deliver.”

Wilhelmina delivered. For the next five years she went around the world, from South America to India to Hong Kong to Lapland. She drove herself hard, never taking vacations and often working twelve-hour days, lugging her fifteen-pound mailman’s bag full of model’s tricks, sometimes working from 7:00 A.M. to midnight. “She was the salt of the earth,” says hairstylist Kenneth Battelle. “She was a model before she was a person, a doll and happy to be that.”

“She was so sweet and generous to me,” remembers photographer Neal Barr. “She and Iris Bianchi and Tilly Tizani would do anything for you. You could book them for an hour. Wilhelmina would arrive in her limousine, makeup totally on, open her bag full of hairpieces on foam things, ask what you wanted, be on the set within fifteen minutes, do the shot, jump back in her limousine, and be gone.”

Barr remembers that most of the models when he started his career in the early sixties were “totally emaciated, veins sticking out, faces literally stenciled on.” But Wilhelmina was different; she was a very big girl. “I was on continuous diets,” she recalled. “I’m not fat as far as real life is concerned, but I certainly was when it came to modeling. I ate twice a week. In between, it was cigarettes and black coffee. On Wednesday, I had a little bowl of soup so I wouldn’t get too sick or a little piece of cheese on a cracker. On Sunday, I’d have a small filet mignon, without salt or any sauce. I was running on nervous energy as well as determination.” Still, she had to keep her figure under wraps, often wearing both a regular girdle and a chest girdle to flatten her bust.

In Paris a colleague introduced Willie to diet pills. No one cared what a model put into herself, as long as she performed. “I found myself walking along the Champs-Élysées with the cars coming towards me, but my body had no reaction whatsoever,” she said. Finally she developed something she called the Hummingbird Diet and alternated it with binges.

Wilhelmina dated many men in her first years in New York. Early on “she was very involved with a tall dark actor,” Jovanna Papadakis remembers. “I didn’t care for him. She was making a lot of money, and he was using her.” Wilhelmina knew that. “They take you out because they want to be seen with a beautiful woman,” she said of New York’s playboys. “It’s easy here to be used as a display doll. But as a model, it’s important to be seen at nightclubs and restaurants.”

Then, in 1964, she met Bruce Cooper. Born in Ballard, Washington, Cooper later told reporters that he’d grown up in Shawnee, Oklahoma, served four years in the Navy, and entered show business as a San Francisco disc jockey. He later became an associate producer on The Tonight Show, where he booked guests and wrote questions for Johnny Carson. When Willie was nominated as one of the ten best-coiffed women in America, Cooper booked her for an appearance on the show. She forgot to plug the hair products she was meant to claim she used (although, in fact, she didn’t), so afterward she was nearly hysterical. Cooper took her out for a martini. “I was fascinated at how fast she could change hairpieces,” he later said.

They started dating, but Willie still played the field. “I was involved with a rich old man,” she said, “who showered me with gifts—including a huge bouquet every day.” He also provided her with a limousine. Cooper fought back. “Once in a while, I got a perfect rose from Bruce,” Willie said. “It made me mad, but I never knew why. Sometimes I was actually rude to him.”

Late in 1964 Cooper gave her a huge marquise-cut diamond ring, and they got married on the Las Vegas Strip in February 1965, with The Tonight Show’s Doc Severinson and Ed McMahon in attendance. In what their daughter, Melissa, later took as a sign of the pretense that characterized their relationship, their wedding photographs were staged after the actual event.

Handsome and fast-talking, Cooper presented a compelling facade. But behind it, says Melissa, there was turmoil. Bruce Cooper was a paradigm of the bad choices many models make in men. “We were all virgin princesses, and we all married creeps,” ex-model Sunny Griffin observes. “Nice guys thought we were stuck on ourselves.”

Cooper beat Wilhelmina. “A couple times she came to bookings with black eyes,” remembers Kenneth Battelle. “There were products you could cover black eyes with. She had all that. But she never talked about it. It was a more disciplined time. You wouldn’t spew your personal life out to anybody.”

Indeed, Wilhelmina’s problems with Bruce remained a secret for years. But after both her parents died, Melissa Cooper looked into her father’s past and discovered its tragic dimensions. “Bruce’s mother was most likely a prostitute,” Melissa says. “She lied to him about who his real father was. He had seven fathers and a lot of uncles, and every night there was another man. She started him hating women. He was a misogynist in every sense.”

After siring three children by his first wife, Cooper was divorced and married a neighbor. That marriage ended some time after he stabbed his second wife’s first husband. Charged with attempted murder, he was briefly institutionalized. “Bruce left all that behind when he came east,” Melissa says. Resettled in New York, he married his third wife, Bobbie, who was a house model at Hattie Carnegie and had come to Eileen Ford seeking more work. “He wouldn’t give her any money,” Eileen remembers. “Bruce Cooper was a brutal man.” Adds Jerry: “He had creep written all over him.” Soon, Bobbie was out and Willie was in.

The Coopers and their two poodles moved into a big apartment on Central Park. A zebraskin rug adorned Bruce’s den. He’d left The Tonight Show and planned to become a manager of opera singers. She continued modeling for two years after their marriage. Now her dress size—12—was accommodated, not criticized. When a sample didn’t fit her, stylists ripped open the back and underarm seams and pinned in matching linings to hide their work. Even the English admitted her importance. “Wilhelmina,” the Daily Express declared in 1967, “puts the Shrimp and Twiggy in the shade.”

But after seven years her bookings suddenly started dropping off. “She thought she was over the hill,” remembers Fran Rothschild, a neighbor and a garment center bookkeeper. Then Irving Penn told Wilhelmina that Eileen Ford had said Willie was unavailable on a day when she was actually free. “Eileen took work away from her to give it to her new girls,” Rothschild says Willie concluded.

Eileen had a lot of new girls. On their twentieth anniversary Jerry Ford told The New York Times that the agency was billing $100,000 a week. That money helped the Fords buy a new computer system, the first in the model business. They needed it. In 1967 they claimed their 175 female and 75 male models controlled 70 percent of the bookings in New York and 30 percent in the world. Ford’s stars included Harper’s Bazaar cover girl Dorothea McGowan, Agneta Darin, Babette of Switzerland, Dolores Hawkins, Dolores Ericson, who’d just appeared on the cover of jazz trumpeter Herb Alpert’s Whipped Cream and Other Delights, and Vogue’s newest favorite, Lauren Hutton.

Another Ford star was Sunny Griffin, who’d replaced Wilhelmina as the agency’s top model and was earning six figures a year. She’d come to New York from Baltimore in spring 1962 and joined Ford. Two years later, having hardly ever worked, Griffin was told the agency was cleaning out deadwood. “And you’re it,” Ford said. Griffin begged to be sent to Dorian Leigh in Paris instead. Nine months later Ford cabled her to come home immediately. A catalog studio wanted to put her under contract. Griffin also got a contract with Kayser-Roth, an underwear manufacturer. At first Ford told the company it was still the agency’s policy to turn down underwear work, a holdover from the era of “objectionables.” “They asked Eileen what it would take,” Griffin remembers. “She said five hundred dollars an hour and five thousand dollars a year. They said yes. From then on, Ford models did lingerie.”

By 1967 Griffin was part of the Ford family. “We’d go out to Quogue every weekend” to the Ford’s huge beach house, she says. “If you were married, you were invited with your husband. Eileen cooked Friday night dinner, big pots of mussels. At Eileen’s you always got enough to eat.” Griffin remembers a family scene. The Fords’ eldest daughter, Jamie, had gotten married and moved away, but the other three children were always there. “Katie and Lacey had to curtsy when they came in the room until they were sixteen,” Griffin remembers. “Billy Ford lived on the fourth floor with all the Swedish models, having a good time, fucking them. Eileen was blind to it, but she finally figured it out,” and young Billy had to give up his roommates.

Griffin thought Ford both eccentric and psychic. Griffin remembers, “She never looked at you, but the next day she’d tell you how many buttons you had buttoned. One day, when I first started, she grabbed me and started plucking my eyebrows. She scared me to death, but she was right. She was a great model agent. And she was a mother tiger to her models. One time a photographer exposed himself to Dorothea McGowan. He never worked again. Ford was that powerful.”

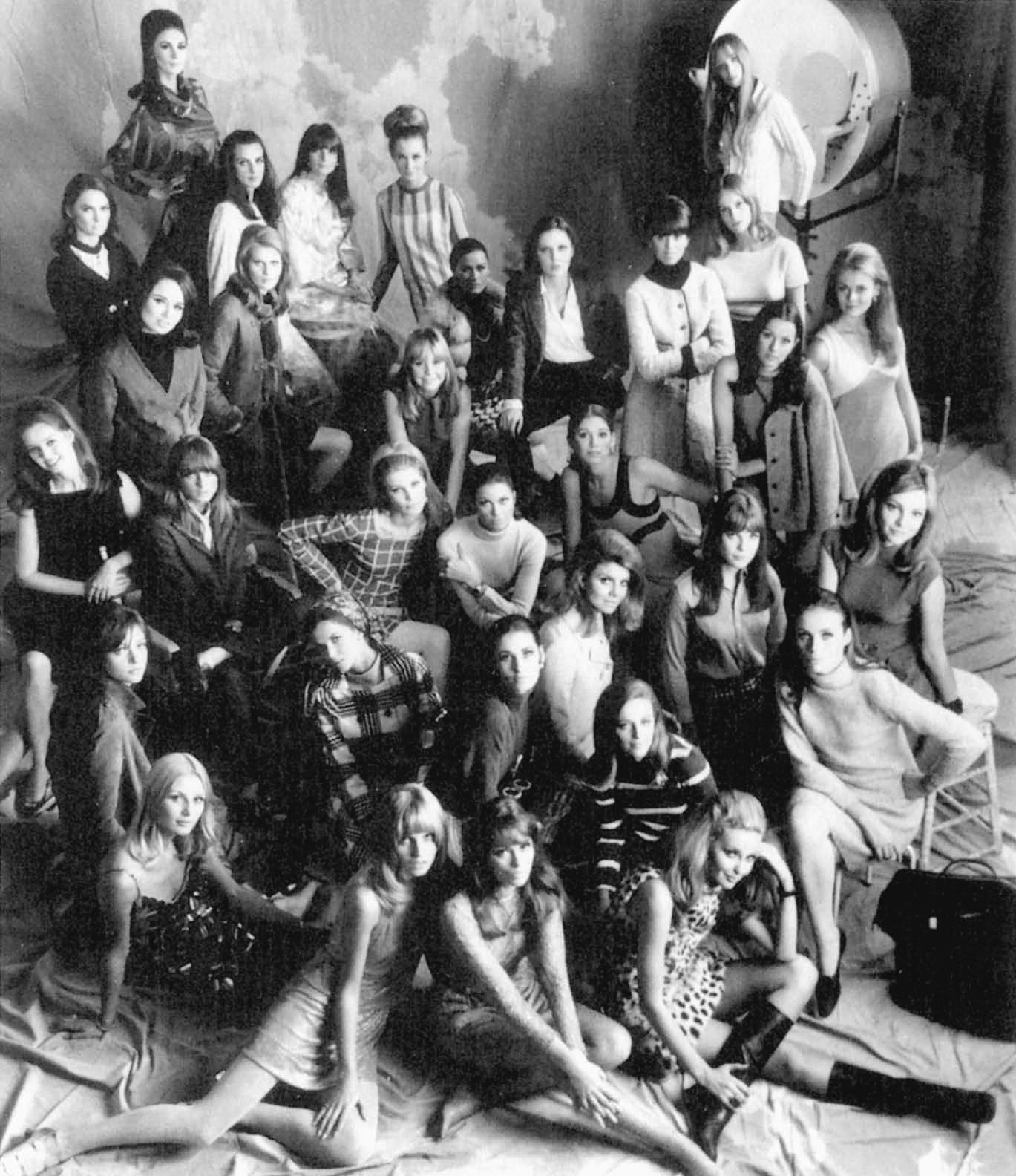

Thirty-two Ford models photographed by Ormond Gigli. Top: Wilhelmina; left to right, second row from top: Barbara Janssen, Tilly Tizani, Iris Bianchi, Sondra Paul, Melissa Congdon (in front of light): third row: Sondra Peterson, Hellevi Keko, Holly Forsman, Maria Gudy, Donna Mitchell, Diane Conlon, Agneta Frieberg, Dolores Hawkins, Agneta Darin; fourth row: Victoria Hilbert, Editha Dussler, Ann Turkel, Veronica Hamel, Renata Beck; fifth row: Babette, Margo McKendry, Astrid Schiller, Heather Hewitt, Helaine Carlin, Pia Christensen; on floor: Anne Larson, Heidi Wiedeck, Astrid Herrene, Sunny Griffin (in stripes), Samantha Jones (in spots), Ericha Stech (sitting on stool)

Thirty-two Ford models by Ormond Gigli, courtesy Staley-Wise Gallery, New York

So it was no wonder Wilhelmina felt Ford had the power to take her work away and give it to models like Griffin. Says Jerry Ford: “It’s a very familiar song. When a photographer uses a model a lot and then doesn’t and then bumps into her, he doesn’t say, ‘You’re too old.’ He says, ‘God, I’ve been trying to get you.’”

Regardless, Wilhelmina and Bruce decided to form an agency of their own. Cooper was “the engine,” says their daughter, Melissa. “He had great ideas. She made them happen.” But Willie deferred to Bruce. “He’s the big boss,” she said. They asked Rothschild to handle the numbers. “I knew nothing, except she was my friend,” Rothschild says. “She gave me her diary, so I could learn how she worked. No one kept records like she did.” With seed money of $200,000, they incorporated Wilhelmina Models on April 18,1967.

When Wilhelmina opened on Madison Avenue that July, its namesake was the only model. “Everyone called and said, ‘Thank God, now I can get her,’” Rothschild says. Willie’s earnings—$17,000 in the first month alone, at the new star rate of $120 an hour—kept the agency afloat as she scouted for more talent. Other Ford models soon came. Dovima came, too. By 1967 she’d decided that “the producer and the casting couch life wasn’t for me,” she said. She returned to New York and joined Wilhelmina, where she was put to work interviewing aspiring models and helping Willie with the seminars she held on makeup and fashion flair.

But had Dovima really given up the casting couch routine? “Bruce was stuffing her,” Carmen Dell’Orefice says flatly. “Everyone knew he was a monster, but we protected Willie. We loved her.”

By 1969 European models booked half of Ford’s business. There were more magazines in Europe, yet there was less money involved, so editors and photographers were more willing to take chances on new faces. And in a fashion world hooked on novelty, European models were something new. “They’re green grass,” said Jerry Ford, “and they know what they’re doing when they arrive here.”

New York was their mecca for a simple reason. “That’s where the money is,” Wilhelmina explained. So one of her first moves after opening her doors was to plan a trip to Europe to see the agents there. By the mid-sixties there were a lot to choose from. In Paris two competitors to Dorian Leigh had sprung up almost immediately.

Diane Gérald, Dorian Leigh’s former assistant, had gone to work at a rental service called Paris Planning. Before long she and its owner, François Lano, turned it into a model agency, opening their doors on the rue Tronchet in October 1959. Leigh replaced Gérald with another young Frenchwoman named Catherine Harlé. But then she, too, left, announcing she was starting an agency, too.

Agent and rabatteur Jacques de Nointel (left) and François Lano of the Paris Planning agency

Jacques de Nointel and François Lano, © Michael Gross 1995, all rights reserved

Leigh had taken fees only from her clients—the magazines, advertisers, and fashion houses. “She asked fifty francs a month for the right to call anytime,” Lano says. He decided to charge his models a commission as well. “I said, ‘I’m not interested in this just to have groovy people around me. If I do this, I do it for money,’” he recalls.

Harlé opened shop in the Paris suburb of Levallois. Her first star was Nicole de la Margé. Discovered by an editor of Jardin des Modes magazine while working for a Paris dress wholesaler, the girlish Margé, mousy without makeup, was the quintessential French model of her era. “The age of the aloof model was over,” she once said. “I was the anti-Suzy Parker—the girl next door could look like me.” Moving to Elle, she became the girlfriend of art director and photographer Peter Knapp and the magazine’s visual image, appearing on about 150 covers before quitting the business in the late sixties. After marrying a journalist for Paris Match, she died in a car crash in the early seventies.

Dorian hadn’t been resting as all this agency opening was going on. In 1960 she’d met Paul Harker, a wealthy businessman who co-owned Mirabelle, one of London’s leading restaurants, and Annabel, a private club. He offered to finance an agency in London. But Leigh loved life a little too much, and that eventually proved her undoing. “Dorian was a very big drinker,” says Stéphane Lanson, then a male model with Harlé. When she wasn’t drinking, she was usually with a man. Photographer Brian Duffy, for instance. He was one of six men Leigh slept with late in 1960, when she decided to have another child, following the collapse of a brief marriage to her gynecologist. That same year Leigh was evicted from her apartment in Paris when her landlord discovered she was running her business there. The Fords came to her rescue with a $16,000 loan for key money on a new place.

In 1963 Dorian hooked up with Iddo Ben-Gurion, a distant relative of Israeli leader David Ben-Gurion. “He arrived in my agency, looking glorious, of course, and said he’d written a book and named one of the main characters after me,” Leigh remembers. “He announced he was going to make me famous and we were going to get married. Eventually I got worn down by his salesmanship.” Leigh introduced Iddo to the Fords when they came to Paris in spring 1964, and they adored him. The couple’s wedding caused Dorian’s sister, Suzy Parker, to quip that she’d done it only to be Dorian Ben-Gurion. They honeymooned in Switzerland, where Dorian kept numbered accounts to avoid taxes, en route to Israel.

Catherine Harlé in her Paris agency in 1965

Catherine Harlé by Georges Bordeon, courtesy Jérôme Bonnouvrier

Over the course of the next two years Dorian Leigh’s agency died. “Her business was failing,” says Eileen Ford. She’d already lost the London and Hamburg offices. The Fords hoped Iddo would add stability. But models weren’t being paid. “Dorian wasn’t on top of her business,” says Jerry Ford. “The competition was outstripping her.”

Then Iddo Ben-Gurion disappeared. Dorian says, “I discovered that I owed a lot of money to models because Iddo was jogging to the agency every morning and picking up the mail. He’d opened a numbered account in Germany and was depositing all the checks. I went to the bank in Germany and proved to the bank that none of my signatures or the models’ signatures were true. He had even taken out a Diners Club card and signed my name.”

Leigh says she called Eileen Ford in New York and told her what had happened. She added her suspicion that Iddo was on drugs. (Several years later Ben-Gurion died of an overdose.) But the Fords didn’t believe her. “He was a good guy to my knowledge,” says Eileen. “Iddo was the most wonderful man in the world,” Jerry adds.

Months later Leigh heard what happened after her call to the Fords. “The minute you called about Iddo, Eileen picked up the phone and called François Lano at Paris Planning and said, ‘Would you like to work with me?’” Leigh was told.

“We had to do something,” says Jerry. “Dorian was not in the game. We knew she felt she owned us and we shouldn’t talk to anyone else. That was the beginning of the fallout. We told Dorian we had to work with someone else. We felt badly about it. But we never proposed we not work together. There was no question who our favorite was. We wanted to help Dorian.”

Bobby Freedman, a businessman-around-town and friend of both Dorian and the Fords, intervened. Freedman was best friends with Bernie Cornfeld. “Bernie said, ‘Why don’t I back you?’” says Dorian. Cornfeld was part of the new postwar jet set, one of the rich businessmen who hopped from continent to continent, living the good life. Born in Istanbul, Turkey, in 1927, Cornfeld grew up in Brooklyn, where he was briefly a social worker before founding Investors Overseas Services in 1958. A onetime socialist and flamboyant salesman, Cornfeld claimed he created IOS, which grew into a $2.5 billion banking, mutual fund, insurance, and investment trust empire in the go-go sixties, to “convert the proletariat to the leisure classes painlessly.”

In 1969 Cornfeld took IOS public, but he lost control of the company in 1970, after its share value had dropped from a high of $25 to about $1. He resigned from its board the following year, after turning control of the company over to financier Robert Vesco, who, he claimed, “walked off with the cash box.” In 1973 Cornfeld was arrested for fraud and jailed in Switzerland for almost a year, but he was later acquitted. Vesco, charged by the Securities and Exchange Commission with siphoning more than $200 million from IOS, remains a fugitive.

In the 1960s Cornfeld was still riding high. “I was friendly with Eileen and Jerry Ford,” he says. “They had absolutely stunning women, and every time I was in town, they would organize a party and let the girls know these were people they should be marrying, or if not marrying, then fucking.” One weekend Jerry Ford asked him to look over their company. “It was our dream at that moment to get Dorian and François together,” Ford says. “I’d tried to buy Paris Planning, but I had no money. Bernie said he’d invest, but he wanted us to merge with Dorian.”

Cornfeld looked at Ford’s books, “and the bottom line was only fifty thousand dollars,” he says. “They lived off the agency. So I put together a plan for them to buy an agency in each key area of Europe. I was going to finance the acquisition and arrange to have it go public.”

The deal fell apart, Cornfeld says, after Eileen Ford was rude to a girl Bobby Freedman was seeing. “She wanted to be a model,” Cornfeld says, “so Bobby arranged for her to meet Eileen. Eileen kept her waiting a couple hours and then said her mouth wasn’t right, her nose wasn’t right, she’d never be a model. Eileen’s not a bad gal, but the girl left her office devastated and in tears.”

Cornfeld then met Dovima. After two years at Wilhelmina, she was ready to move on. Just months after joining the Coopers, she’d written a proposal seeking backers for her own business. “The time has arrived for the Dovima Agency to appear,” it said. In fact, it hadn’t, but Dovima kept trying and finally she opened Talent Management International for Cornfeld.

TMI, as it was known, never really had a chance. It did respectably. But with Cornfeld’s legal problems mounting, he shut it down. Thus Dovima’s career ended. Soon she was a salesgirl at an Ohrbach’s clothing store. After contracting pneumonia, she moved to Florida in 1974 to be near her parents and took a job in a dress shop. “I have put away my false eyelashes,” she said.

Finally, she found happiness when she met West C. Hollingworth, a bartender in a restaurant on the Intercoastal Waterway where she worked as a hostess. “She finally met somebody who loved her,” says her model colleague Ruth Neumann. “She didn’t care that she was waiting tables.” She married Hollingworth in 1983. The next year she got another hostess job in Fort Lauderdale’s Two Guys Pizzeria. But somehow, Dovima couldn’t avoid a tragic script. Hollingworth died in 1986, and soon afterwards she discovered she had breast cancer and had a mastectomy. For the next four years she remained in Fort Lauderdale, alone, scared, and often “drunk as a skunk,” says model Nancy Berg. Dovima died in 1990. In a show of loyalty that still brings a catch to Eileen Ford’s throat, Dovima named her ex-agent her estate administrator.

“I went to open her safe-deposit box,” says Ford. “She only had a hundred dollars in it.”

The next intrigue in the European model war paired Paris Planning’s François Lano and his rival, Dorian Leigh, who conspired to gang up on the Fords. “Jerry had offered to work exclusively with François, and François was stupid enough to believe it!” Leigh says. “They told every agency that. I said to François, ‘Eileen won’t let you get big. She should pay us! We find them, we train them, and we never hear from them again.’ Eileen was double-dealing everybody. She was running every agency in France and Italy!”

Once the Paris agents started talking, they agreed to take action. “We formed an association of model agents in Paris,” Leigh says. “I felt we should all work together and get proper payment from New York for the girls we were finding and developing.”

On Lincoln’s Birthday 1966 Leigh and Lano flew to New York to present an ultimatum. The luncheon meeting went badly. Lano and Leigh took the position that they shouldn’t pay commissions because they trained Ford’s young models. “But they wanted us to pay,” says Jerry Ford, “and we wouldn’t.”

“It was awful,” says Leigh. “Looking me in the face, Jerry said to François, ‘Why work with Dorian? We’ll pay you to work with us. We’ll destroy her.’ François said, ‘Dorian, we made a deal, but since they don’t want you, I’ll make my own deal with the Fords.’ By offering François exclusivity and money, she broke off our very tenuous relationship.”

Says Lano: “It was impossible to stop working with Eileen.” Nonetheless, Dorian was about to.

Every couture season in Paris the Fords paid for Dorian to throw a party. But when Eileen called from Rome in 1967 to make the arrangements, she couldn’t get Leigh on the phone. Eileen told Jerry something was wrong. He told her she was being ridiculous. If she didn’t get through from Rome, certainly she’d talk to Dorian in Paris. But a few days later, when Eileen arrived at the Hôtel St. Régis, she still hadn’t made contact. So when Hiro, a Bazaar photographer, suggested they go to the party together, Eileen reluctantly agreed. The fete was in a photographer’s studio. “Dorian was at the door,” Ford says. “She’d had a sip or two. She said, ‘What are you doing here?’ I said, ‘Do you want me to leave?’”

“You can leave by the door or I can throw you down the stairs” was Leigh’s acid reply. A few days later the entire exchange was printed in a New York gossip column. The Fords still blame Leigh for the item. The twenty-year love affair between the mothers of modeling was at an end.

The Fords soon began working with a new agency, Models International, formed by the husbands of two European models, Simone d’Aillencourt and Christa Fiedler. Dorian had booked them both and believes their spouses “saw how much money they made and thought, Why should Dorian get ten percent of it?” she says.

Now, cut off from the Fords and from two of her top earners, Dorian was flying from New York to Paris when Jacques Chambrun introduced himself. He was a literary agent, representing Somerset Maugham and Grace Metalious, the writer of Peyton Place, among others. He also owned 16 magazine in New York. “He had been a priest,” Leigh deadpans, “and he was very interested in models, and he said, ‘I understand that you’re having financial difficulties.’ I gave parties twice a year, and I traveled to find models, and I said to Jacques, ‘I really can’t afford to travel anymore to find models.’ He said, ‘I’d be glad to go with you and pay for it.’ So we went to Copenhagen and then to Sweden, and he paid for it all. In the course of that, I met a Swedish girl, a nurse, and asked her to come to Paris to model. Jacques fell madly in love with her, and she moved into his house on Avenue Foch, and she went to New York, worked with Eileen. In the meantime, Jacques would pay for the receptions that I gave. I gave parties at his house on Avenue Foch for Elizabeth Taylor and the Maharani of Baroda. I cooked cassoulet for a hundred forty people.”

But Dorian’s parties at Chambrun’s hôtel particulier were known for more than her cooking. Nude girls cavorted in the basement pool, visible through an underwater window in his bar. “I thought, He gets his kicks because he’s so unattractive that he just likes to watch beautiful young girls and men having a wonderful time,” Leigh says. “And he liked to feel that I was his friend.” She asked him to lend her $16,000 to pay her outstanding debt to the Fords. Chambrun had his lawyer draw up papers. But then the lawyer called Leigh, “in shock,” she says, and told her Chambrun was buying her agency for $16,000. Dorian called off the deal. Then Chambrun called her. “You’ll still invite me to your parties?” he asked.

Simone d’Aillencourt (foreground) and Nina Devos photographed by William Klein in Rome in 1960

Simone d’Aillencourt and Nina Devos by William Klein, courtesy Howard Greenberg Gallery

By 1970 Leigh’s business was nearing insolvency when, with impeccable timing, Bernie Cornfeld turned up again. “I remember sitting at the lunch table with Dorian and Bernie,” says Jérôme Bonnouvrier, who went to work for his aunt Catherine Harlé in 1967. “He looked at her like a prostitute. He pulled out a pack of five-hundred-French-franc notes and told her he wouldn’t do business with her, but he’d help her. Dorian threw the money back at him.”

Leigh soon lost her apartment and was forced to sell all her belongings. “She’d entertained all of Paris, and suddenly no one was around,” says Bonnouvrier. Finally Dorian Leigh closed, “merging” with Catherine Harlé to save face and celebrating with a party at Jacques Chambrun’s house, featuring naked girls in the swimming pool.

“That’s when my darling friends got together and said, ‘You’ve been cooking for your friends for years, you might as well do it for a living,’” Leigh recalls. With investments of $1,000 each from several photographers, she opened a restaurant in Fontainebleau, outside Paris, the next summer, and spent the next four years there. She was well rid of the modeling business. “I could no longer ask a beautiful girl to be a model,” she says. “I couldn’t say it would be a wonderful life.”