A few nights before Elite opened in New York, Zoli Rendessy tossed one of his famous all-star parties. Apollonia von Ravenstein came with Ara Gallant, the hairdresser who counted Jack and Warren and Anjelica among his very best friends. Apollonia and Ara were a couple of the moment, but that didn’t mean they slept together. Indeed, after Zoli’s party Gallant headed off alone to the Anvil, a bar near New York City’s downtown docks, where the entertainment consisted of men fist-fucking other men. “I love the Anvil,” Gallant said. “Of course, it would be extremely embarrassing to be caught fucking there.”

Embarrassment may have been the last taboo, but discretion was out of fashion.

“Me with four men?” says a Wilhelmina model of the era. “Sure.”

With uncanny synchronicity, Studio 54 had opened a few weeks before Elite, and it quickly became a symbol of the revival of recession-plagued New York. It was also a symbol of the prevailing social ethic of libertinism, dissolution, and the quest for easy gratification. Drugs—especially cocaine and the soporific Quaalude—were given away like candy by the club’s co-owner Steve Rubell and consumed by all and sundry. Semipublic sex took place regularly in the club’s balcony and basement.

The rules of acceptable conduct had changed. The exotic and unspeakable had become the new norm. The models, agents, and photographers who joined the dancing sea of celebrities were central figures in a new society—the first, perhaps, since the fall of Rome to declare so openly and in such numbers that sin was in. They all believed they were special, and Studio’s exclusionary door policy reinforced that notion. Above morals, above ethics, and especially above those kept waiting outside, Studio’s denizens were modern Olympians, inhabiting a special world of notoriety. And the wages of their sins were astonishing. Each new excrescence brought them more celebrity, more reverence, and more money to fuel their shenanigans.

The addiction to pleasure was international, and models were in the vanguard of the pleasure seekers. Thanks to John Casablancas, models had become rootless mercenaries, traveling the world in search of bigger bucks. In the late seventies no one earned more than Cheryl Tiegs, whose day rate hit $2,000 in 1977. Although many assumed that her husband, Stan Dragoti, was running her career, Tiegs insists she was in charge. “I pretty much did it myself, for better or for worse. I certainly made mistakes along the way. But I was very much a long-term thinker.”

Tiegs downplays the importance of her January 1978 appearance—in a fishnet bathing suit that bared her full breasts—in Sports Illustrated’s annual swimsuit issue. “It’s a sweet little picture, that’s it,” she says. But in fact, it was a major coup, adding the powerful appeal of the pinup picture to modeling’s arsenal of promotional gimmicks.

“It was our last day of shooting on the Amazon River,” recalls SI’s Jule Campbell. While Walter Iooss, Jr., was shooting a young Brazilian model, “Cheryl was waiting in the boat, getting impatient because we weren’t using her,” Campbell recalls. “I told Walter to get a picture of her and send her back to the hotel. She got in the water, but she was annoyed, and she was just standing there to get it over with.” Back in New York, Campbell decided against using the picture but showed it to her editors just in case they liked it.

They did. And the response was overwhelming. The magazine’s swimsuit extravaganza had always been the second best-selling issue of the year, just behind its Super Bowl special. “That year I beat the Super Bowl,” Campbell says. “They had posters of the photograph in Times Square the next day, and we had to sue to stop it. We got letters from outraged mothers, librarians, priests telling me I was going straight to hell. We never turned back. And Cheryl’s career took off after that.”

Two months later Tiegs appeared for the second time on the cover of Time and was featured in its competitor, Newsweek, the very same week. “Where else could I go from there?” she asks. “It was time to move on.” In rapid succession she posed in a pink bikini on a poster that knocked Farrah Fawcett-Majors off the walls of the rooms of several million adolescent American boys, announced a deal to write a book on beauty, and signed what was reported to be a $2 million contract to appear on ABC-TV.

“My whole world turned upside down, and I certainly noticed the difference,” she says. “Whatever I did was recorded on the cover of the New York Post. I wasn’t in as much control as I would have liked. I didn’t know how to stop it. The media kind of threw me for a loop.”

Tiegs won’t talk about what happened next. Indeed, she answers questions about the next three years of her life with stony silence. But just as her career hit the stratosphere, her marriage to Dragoti ran aground, and she became the first victim of the new, heightened interest in models. In 1978 the New York Post and its competitor the Daily News were locked in tabloid combat. Gossip items were part of the ammunition they used in their war, the more scurrilous the better. Tiegs got caught in the crossfire.

That December Tiegs was reportedly spotted necking with tennis player Vitas Gerulaitis at a birthday party for Steve Rubell at Studio 54. Not long thereafter she flew to Kenya with photographer Peter Beard to narrate an American Sportsman Special documentary based on Beard’s book about African wildlife, The End of the Game. Five months later, en route to the Cannes Film Festival, Dragoti was arrested at the airport in Frankfurt, Germany, with about an ounce of cocaine, wrapped in aluminum foil, taped to his back and thirty more grams of the stuff in his suitcase. In July, after he was fined almost $55,000 and given a suspended sentence of twenty-one months in jail, Dragoti said he’d started sniffing the stuff after he learned that Beard and Tiegs had begun having an affair in Kenya. “I was very depressed,” he said, “and needed something to take away the pain.”

Peter Beard had been involved with models for twenty years before he met Cheryl Tiegs. In 1958 the Yale student and photography buff was a patient in New York’s Hospital for Special Surgery when Suzy Parker was wheeled into the next room following the train crash that killed her father. “Seeing her and the various people who came in to see her was my first entrée to the world of what Diana Vreeland called the beautiful people,” Beard says.

Out of college in the early sixties, he began taking fashion and beauty photographs for Vogue. Alex Liberman sent Dorothea McGowan to him for one of those sittings. Beard says, “I hate clichés, but she had star quality. It’s a certain inner light that emanates from some people. Dorothea couldn’t take a bad picture. A photographer is basically a parasite on his subject matter.”

Beard remained with McGowan for several years, until he went off on a shoot with Veruschka and a German model, Astrid Herrene. “Dorothea got totally bent out of shape because Astrid and I were having a bit too much fun together, so to speak,” says Beard, who subsequently married and divorced socialite Minnie Cushing and dated Jacqueline Kennedy’s sister, Lee Radziwill.

After a while, Beard says, he came to hate fashion, “a horrible, shitty little industry governed by phonies. Harper’s Bazaar was by far the better magazine. Vogue had all the money and the boredom and a very confused collection of social-climbing people who were ruining the creative process. They ruined Bert Stern; they ruined William Klein with their lack of vision. All the great photographs were put on a shelf.”

In 1975 Beard went to the Sudan, where he discovered Iman Mohamed Abdulmajid, the daughter of a diplomat and a gynecologist. She was a student at the University of Nairobi when Beard spotted her on the street with Kamante, the majordomo of Isak Dinesen, the author of Out of Africa. “Iman was dead anxious to get out of Africa,” he says. That October Beard brought her to Wilhelmina and called a press conference to introduce his discovery to the fashion world. He claimed he’d met her on Kenya’s northern frontier “because it’s not very interesting to meet somebody on Standard Street in a disgusting tourist town like Nairobi,” he says. The reporters at the press conference embellished Iman’s tale further. Newsweek called her “a Somali tribeswoman … part of a nomad family in the East African bush.”

“They made up a lot of lies that we didn’t think of,” Beard recalls gleefully. He and Iman were never an item, although “everyone thought we were,” he continues. “It was just mutual admiration. Everyone immediately realized the delicacy, strength, and poise of this African woman. She hadn’t forgotten how to walk. She’d not been spoiled by the galloping rot.” Though she had a hard time at first (“The Black Panthers were after her,” Beard says), Iman soon became one of the top models of her time. She was once reputedly paid $100,000 for appearing in a single fashion show.

Iman married basketball star Spencer Haywood in 1978. One year later, while playing for the Los Angeles Lakers, he became a cocaine casualty. Though he later said that his wife never knew his full involvement with drugs, as a glamorous couple in L.A., he recalled, they went to parties where silver plates of cocaine were served like hors d’oeuvres. But Iman’s world was at least as drenched in drugs as Haywood’s. “I shot doubles with Iman and Janice Dickinson,” says one photographer, “Janice would come here, and if I was out of coke, she wouldn’t do the shot. Everyone got so fucked up Iman couldn’t get into a pair of pull-on pants.”

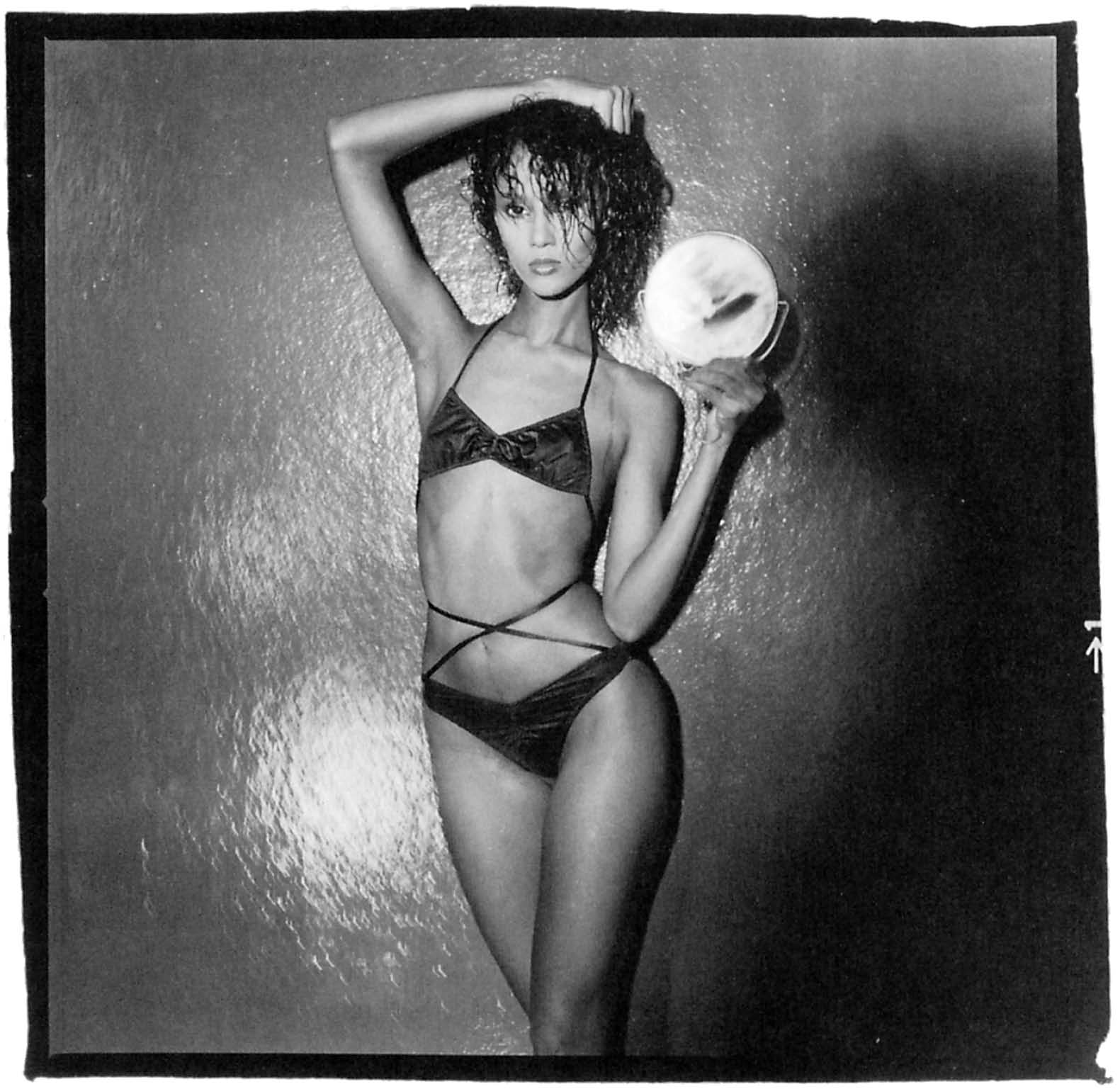

Iman photographed by Anthony Barboza

Iman by Anthony Barboza

In the mid-eighties Iman and Haywood divorced, and she turned to acting. She is probably now best known as a tireless crusader for her native Somalia, and as the wife of glam rocker David Bowie, whom she married in 1992. That same year she lost custody of her daughter, Zulekha, to Haywood, who, ten years after kicking drugs, now renovates housing for low-income inner-city families.

In fall 1979 Cheryl Tiegs signed the largest cosmetics contract ever written with Cover Girl, which reportedly agreed to pay her $1.5 million over five years. The following summer she signed another major contract with Sears, to create her own line of clothing. The ongoing soap opera in her personal life was apparently no problem for the Middle-American catalog house. It was announced that Dragoti would shoot her commercials, and Beard was slated to photograph her print ads.

Dragoti was seen out and about with Zoli’s Jan McGill and Ford’s Lisa Taylor before he finally sued Tiegs for divorce at the end of 1980. It became final the next May, and Tiegs immediately married Beard in Montauk, Long Island, where they took up residence. In spring 1982 they split up. He went to Kenya. She went out with—if the tabloids were to be believed—hockey’s Ron Duguay, tanning’s George Hamilton, Superman’s Christopher Reeve, and an unidentified man she was spotted passionately kissing on the street. By the end of 1983 Tiegs was seeing her future third husband, actor Gregory Peck’s son Tony, a boy-about-town ten years her junior.

What happened? Peter Beard can’t say. Their 1984 divorce agreement—signed after reports of extramarital affairs, changed locks, clothes thrown out windows, and bitter disputes over Beard’s Montauk property—forbids either of them to talk about the other. Jerry Ford says Beard was the problem. “I like Cheryl a lot, and Peter was a real shit to her,” he says. “He let everyone know that he thought she was the stupidest woman in the world. He’s a little crazy. His is not an everyday kind of brain.”

Others say drugs were the problem. “Cheryl was doing coke before anyone,” says a magazine editor who knew her well. “She was heavy on it. At the wedding in Montauk they handed out silver vials.” Then there are those who say Tiegs was attracted to danger. “Women just go crazy over Peter,” says model Bitten Knudsen. “He’s very rustic. They want this adventurer. It’s a turn-on to try and tame this wild man.”

Tiegs addresses the subject of the turn of the eighties carefully. The tabloid stories “hurt a lot, because a lot of it was not true,” she says. “A lot of it was true, but I didn’t wish it to be published. Even if it were true, it’s none of their business.” Was she promiscuous or a coke user? “I wasn’t, but to even deny it gives it credibility,” she says. “What can one say if somebody calls you an elephant? You know you’re not an elephant, but if they’re going to see you that way, that’s their problem. There were times that I stayed up too late, but that was, maybe, the worst of it.” Sears didn’t care, she continues. “So I was out at a disco, what could they say? I wasn’t home needlepointing, but that was none of their business, as long as I did my job. And I certainly never did anything that would ruin my reputation. I’ve read in the tabloids I’ve had an affair with Muhammad Ali; I’ve read I was up in a spaceship with aliens; I’ve read all kinds of things. That doesn’t make it true.”

Today she is happy and healthy, a mother and wife, who also happens to design and manufacture a vast range of products like eyeglasses, fine jewelry, watches, socks, hosiery, and shoes aimed at the people she says she understands best, Middle Americans. Sitting on the back porch of her house overlooking the Pacific Ocean in California, looking back at her heyday, she says she has no regrets. “A world opened up [to me] during that period of time,” she says. “It was a period of my life when I let go and lived for the moment. If I hadn’t, I think I’d be sorry. It was a big leap in a career, in my life, that I took very quickly, almost too fast, but that’s the way it happened.”

Surviving the recession at the start of the seventies, Wilhelmina became the hottest shop in town, working with several agents in each European city, holding its own model conventions, and signing up models like Patti Hansen, a Staten Island teenager who’d been discovered at a hot dog stand, Shaun Casey (who became an Estée Lauder contract face), Pam Dawber, who went on to television fame as Mork’s Mindy, Juli Foster, who was discovered waitressing, and Gia Carangi, a Philadelphia teenager whose wild ways and sultry looks made her a favorite of photographers from Francesco Scavullo to Chris von Wangenheim, who specialized in pictures that captured the madness of the disco era.

With the money those stars earned (variously estimated at $5 million in 1977 and $11 million in 1978), Willie and Bruce Cooper bought a two-story Tudor mansion with swimming pool, tennis court, and several outbuildings in Cos Cob, Connecticut, expanded their theatrical division (which represented models in television and film), and, in 1978, opened Wilhelmina West, an office in Los Angeles, in an attempt to hold on to models like Dawber, Jessica Lange, and Connie Sellecca when they went Hollywood.

“They were mature and adult and sophisticated and larger than life,” says Kay Mitchell, who started out as the agency’s receptionist and rose to head the women’s division in 1975. “They were a very, very glamorous couple. Bruce helped Willie see what she could do. She was the voice. He wrote the script.”

Despite the pretty facade, Willie’s life was in turmoil. “Willie had a problem, the husband,” says Dan Deely, who opened Wilhelmina’s men’s division when he left Paul Wagner in 1968. “He drank at lunch and got in the way. He wasn’t interested in anything for very long, and he really had nothing to do. He’d write fluffy promotional pieces about the dreamworld of Wilhelmina and how you, too, can become a model. She was the presence, and I think that drove him crazy.”

Bill Weinberg came to Wilhelmina from Ford in 1970. A commercial agent and troubleshooter, he specialized in the kind of subfashion model who brought home the bacon but never saw the cover of Vogue. Eileen Ford looked down on his kind of model, but within two years of his arrival in 1966, Weinberg’s division was bringing in $500,000 a year. Weinberg enjoyed watching the Fords work. “Eileen was the artist, and Jerry was the mechanic,” he says. “People were afraid of her, and then Jerry would pacify them, so bridges were never burned.”

But working for Ford took its toll. “She really ran her ship with a reign of terror,” Weinberg says. “No one wanted to take Eileen on. I’d see her sit at a desk near the main board with people on each side of her who were there for different purposes. She’d be screaming at the person on her left and simultaneously charming to the person on her right. To turn it on and off like that is kind of amazing.”

After the Coopers approached Weinberg in 1970, Jerry Ford called him into his office one day and demanded he sign a contract. When he told Weinberg the document was not negotiable, the executive declined to sign it and asked, “Have I quit or did you fire me?” Two weeks later he got his answer in a letter from Ford dismissing him for breach of fiduciary trust.

As his job evolved at Wilhelmina, Weinberg acquired a small share of the agency and took over many of what had been Bruce Cooper’s duties. “Bringing me in solved a problem, but it diminished Bruce’s role,” says Weinberg. “He’d come in, go through the mail, pinch a couple of fannies, make a few jokes, corral a couple of models, go to lunch for a few hours, and come back with a snootful.” Willie started disappearing from the agency for days at a time “because she’d been roughed up,” Weinberg says. “A couple of times [Cooper] stood up and raved at Wilhelmina when people were around. When he got that way, there was no cooling him off.”

Melissa Cooper was eight years old when her brother, Jason, was born in 1974. A few days later the Coopers released a photograph of Willie and her newborn son. “They had to airbrush it,” Melissa says. “Bruce was with another woman when Jason was born.” When he came back, he gave Willie a black eye.

Melissa describes the world Jason came into at Cos Cob as something out of a bad movie. “There were parties every Sunday,” she says. “Food, booze, mounds of coke, people wasted all over. I never wanted to do cocaine because I’d seen how people acted. Nobody did anything in moderation. I saw sex in the open all the time, since I was little. It was my house. I always investigated. You couldn’t shock me as a child.”

Sometimes Jason and Melissa joined in the celebrations. “Jason doesn’t remember this, but he got drunk when he was two and fell into the pool.” Melissa knew to stay away from the substances her parents provided because she’d overdosed on her mother’s amphetamines when she was three. “I thought it was candy,” she says.

At first Cooper’s drinking was somewhat controlled. “In 1974 he was a charismatic, charming man,” says John Warren, who arrived from Ohio to join the agency as a model that year, becoming Pam Dawber’s boyfriend and a friend of all the Coopers. “Bruce had been around; he’d seen things; he was very bright. But he was also a master of self-sabotage. Being in her shadow was more than he could deal with. He hated being Mr. Wilhelmina.” Bruce’s drinking escalated along with the couple’s fortunes. “He never had a hangover; he never threw up,” says his daughter. “That was Bruce’s curse. If not for the drinking, he would have been so accomplished. He was incredible, articulate, but he couldn’t see anything through.”

By the late seventies Melissa and Jason had learned to stay out of their father’s way. Sometimes Melissa ran off into the woods. As Cooper’s drinking escalated and his behavior grew violent, Willie took to locking the children in a wing of the house. “There were bolts on both sides of the doors,” says Melissa. “He’d go on six-day binges, get totally looped, and mix up his wives and his children. We were all whores.” Just like his mother.

But Wilhelmina was a stand-by-your-man woman. So when there were disagreements in the agency, they were always between Fran Rothschild and Bill Weinberg on one side and Bruce on the other, with Wilhelmina behind him. “It made for bad blood,” says Dan Deely. “From 1978 to 1980 it escalated and escalated and never really ended.”

Finally Cooper’s exploits got to Wilhelmina. They’d met an aspiring model at a convention, and Bruce fell head over heels in love with her. “Nobody could understand it,” says John Warren. “He had me meet her. I told him he was putting me in a strange situation.” Cooper also brought her to the agency to see the head of new models, Kay Mitchell, who considered herself Bruce’s protégée. When she refused to sign the girl up, Cooper went over her head to Weinberg. “I didn’t want to accept her either,” Weinberg says. “Bruce got somewhat insistent; but I knew he was having an affair with her, and I felt it would be unhealthy.”

Cooper set the girl up in an apartment at 300 East Thirty-fourth Street, a building full of models. Then he announced to Wilhelmina that he was leaving her, packed his car, and drove to New York. “He got to Manhattan and called [the girl] from a phone booth,” John Warren recalls. “And she said, ‘I can’t see you. I’m entertaining.’” Cooper checked into a hotel, thought things through, and “went back to Willie on hands and knees,” Warren says. She said she’d take him back if he promised to stop drinking and never see the girl again.

There was only one bright spot in Wilhelmina’s otherwise dismal existence. She’d formed a bond with one of her neighbors in Connecticut, a tall, striking Dutch-Austrian investment banker named Edward “Edo” von Saher, who commuted to New York with her. “We were aware of Edo, and we were glad,” says Dan Deely. “We didn’t talk about it.”

“I was a very good friend of hers,” von Saher says. “She was a very good friend of mine.” Their families were close, and von Saher became Willie’s adviser and confidant. “It was a very sad situation,” he says. “Her life was the business. Her husband was the business. She had nobody to talk to. Everybody needs a friend. If people can’t have friends, then something’s wrong. Bruce had a lot of good points, but he was sick. Willie stayed with him because of the children. She was breaking her butt, keeping things going, keeping the facade up. In spite of what was going on around her, she still got things done. Fran and Bill played an important part. The agency continued to be very profitable. As long as she was well, she could deal with it. But then she got a cough, and it wouldn’t go away.”

For weeks in the fall of 1979 Willie ignored it. After all, she’d been a chain smoker since she started modeling. Finally, von Saher made her see a doctor, who diagnosed pneumonia. It seemed to clear up, but then Willie relapsed and had exploratory surgery in January. Only then did her doctors discover she was suffering from inoperable lung cancer.

“Bruce was unglued,” says John Warren, who was with him that night. “His wife had crushed him, but by dying, she’d destroy his identity.” Warren commuted to Cos Cob and took care of Melissa and Jason for the next six weeks. “Bruce wasn’t capable,” he says. “He’d get drunk and threaten to burn down the house.” Finally Warren took to doubling Cooper’s drinks so he would pass out sooner.

Early in February agency lawyer Charles Haydon drew up a codicil to Wilhelmina’s will. It put two thirds of her shares in Wilhelmina in trust for Jason and Melissa. “If Bruce could have voted their shares, he would’ve had a majority,” Haydon explains. “Willie was concerned about Bruce’s habits. He was shacking up with models all over the country. He put it on their credit card. That’s how she found out. Everyone was concerned about the children. Bruce was completely off the wall.” Haydon’s wife and von Saher were named trustees for the children.

Willie died on the morning of March 1, 1980. She was forty years old. Cooper didn’t learn about the change in his wife’s will until after her funeral, when the Cooper family and about two dozen friends went back to Cos Cob. “We were all sitting on a screened porch, and [artist and Wilhelmina investor] Jan de Ruth took a walk with Bruce,” Weinberg says. “When he came back, he was berserk, purple.”

“Fucking cunt!” Cooper screamed. “I can’t believe she did this. Any of you who knew about this, I’ll get you! And if you think I’m going to that memorial service, you’re out of your minds!”

Wilhelmina was buried on a cold, clear morning. That night scores of models attended the memorial service, along with Cooper, who’d been convinced to appear, Norman Mailer, Calvin Klein, Jerry Ford, and John Casablancas. Riverside Chapel was so packed that the crowd overflowed into two adjoining rooms. But even as they remembered Wilhelmina, nobody could forget there was a model war going on. “I heard people were outside, trying to poach models,” says Dan Deely.

In the weeks after Wilhelmina’s death, fear gripped her agency. Cooper would arrive at the offices drunk and cursing. “I was glad Willie wasn’t around to see it,” Rothschild says. He wanted to fire her and Weinberg. “Bruce made a stand to run the company,” Deely says. “We prepared for the worst. If Bruce stayed, the company would be down the tubes within months.”

In July, after months of acrimony, an agreement was signed. Bruce resigned as an officer and director of Wilhelmina and sold his and his children’s shares back to the corporation in exchange for $16,666 a month plus interest for two years. He was also guaranteed a salary of $45,000 a year for two years, $20,000 a year for nine years after that, and full employee benefits, and he was given the right to open Wilhelmina schools outside of a few major urban areas. Dorothy Haydon and von Saher resigned as trustees, and a bank was appointed in their stead. Weinberg and Rothschild took over the agency, and soon afterward Kay Mitchell quit, she says, “because obviously I was not going to be queen of the hop.”

Wilhelmina’s gross estate totaled $830,000. Cooper eventually got his hands on most of it. “The trustees at the bank didn’t do a damn thing,” von Saher says. “I thought I safeguarded the children’s money, but the law at times provides ways of piercing a trust.” With the proceeds of the sale of Jason’s and Melissa’s stock, Cooper bought three condominiums on a hundred acres in Colorado and moved there with the children. “He tried to be a good dad, but he was like a time bomb,” Melissa says.

Cooper remarried in 1984, to a former Revlon executive, Judith Duncanson. Dorian Leigh, back in America, but still cooking, catered their wedding. Not long afterward Duncanson ran into Eileen Ford in a restaurant. “You should have asked me before you married him,” the agent said. Judith called John Warren and asked, “Why didn’t you tell me he drinks?” After Bruce beat her with a baseball bat so seriously she was hospitalized, she had him arrested in 1988. He moved out, into a farm near their home in Cooperstown, New York, where he died from a heart attack in 1989. The family had his remains cremated, and the ashes were placed in a plastic urn. At the funeral Melissa kicked it, “for Willie,” she says. She also threw a vodka bottle and his favorite glass into his grave.

Bruce Cooper’s alcoholism and all the bad behavior that came with it were never acknowledged by modeling folk. But secret sipping, pill popping, and wife beating were as passé as the Ford agency’s quaint double standards. As the eighties began, it was in to let it all hang out. “People carried coke in their makeup bags, and they’d load up in the dressing room,” says one male model of the time. “If you were at Jim McMullen’s,” a restaurant owned by a former model, “and saw so-and-so going to the bathroom, you’d go, too.”

As the business and the money that came with it grew, “a lot of people wanted the same models and would tolerate anything to get them,” says a former model editor. “You couldn’t say, ‘Your hair’s not done? Go home.’ You were lucky to get them bathed.” It drove some old-times out of the sittings business. “The last one I remember with any clarity occurred downtown for Vogue,” says hairdresser Kenneth Battelle. “All this running into the john! They were so high, and it all had to be redone, and I said, ‘I’m not going back.’”

One day in the early eighties a Neal Barr shoot was stymied by a model who couldn’t get drugs. “The poor girl was on the phone with her supplier, he wasn’t coming through, and she was panicsville,” Barr says. “All I needed was one tight close-up, but she kept moving.” Barr finally secured her head with two-by-fours to get his shot. But just as he was ready to shoot, she started crying, destroying two hours of makeup.

Richard Avedon had no time for it. When a model yawned on his set, he threw her out. When hairdresser Harry King smoked a joint in Avedon’s bathroom, he was banished. But for every fashion professional who hated the new drug scene, there were five more indulging in it. “Behavior absolutely changed; shoots became insane,” King says. “People were on time, and then they weren’t. Girls would show up two, three hours late or not at all. Sometimes they’d be in another country. I remember eight of us in the toilet at Albert Watson’s studio, and he thought we were doing hair and makeup. Albert was lovely but very straight.”

Photographers moved in the fast lane, though. Bill King and Barry McKinley were there. “Everybody kissed King’s butt because he had so much business,” says Dan Deely, “but he was strung out from the very beginning, short-tempered, moody, volatile, brittle. His was the first studio where I heard about drugs.” There was also sex. “Stuff I couldn’t even dream up!” says a model who worked with him. “Stuff he wanted hairdressers to do to him, and if they didn’t, he wouldn’t work with them again!”

Hairdresser Harry King stayed close to his friend photographer Bill King even after their romance ended. And he watched as the photographer’s craziness spiraled. Bill King would go to the Anvil and dance on the bar in a leather jacket, boots, and nothing else. He got models—male and female—stoned and then took pictures of them—the nastier the better. He gave one model Quaaludes and then took pictures as his assistant and another man performed oral sex on her. “He was kind, sweet, lovely and a great photographer,” King says, “but Bill did too many drugs and got off on people’s misfortunes.”

New Zealand—born Barry McKinley, who died in 1992, was best known in public as a men’s fashion photographer. In private, Deely says, McKinley was dealing drugs, got arrested several times, and was threatened with deportation. “We wrote letters supporting him,” Deely says. “But he’d turn on you in a minute. He was evil, miserable, bitter, and very talented. You had to deal with arrogant, egotistical assholes.”

McKinley got so wild he even attacked a model physically. “I had a half day catalog job booked with him,” says Rosie Vela. “But when I got there, he told me he was shooting an ad that would run all over the country.” Vela told McKinley she’d have to call Eileen Ford and tell her the job had changed. He started screaming, “You whore! You bitch! You want more money?” Vela thinks McKinley was high on cocaine. “I saw Barry do blow all the time at work,” she says.

As the art director and McKinley’s assistants joined in the abuse, Vela retreated toward the elevator. “He grabs me just before the door closes and swings me out and starts to slap me and hit me,” she says. When she ran from the building, she thinks the photographer and crew threw rocks at her. Finally she was rescued by a friend and went home. “And guess what happened?” she asks. “Eileen Ford called and said, ‘You left a booking? You’re fired.’ And she hung up the phone. I called back and spoke to Jerry, and he calmed her down. The next day Barry sent me flowers, saying he’d love to work with me again.”

Peter Strongwater started shooting catalog jobs in the early seventies. “It wasn’t so much an art as a mechanical production,” he says. “The girls were the worst. You didn’t get the stars. It was drudgery. You just did it according to the layouts the client tacked to the wall.” Strongwater’s first big job was an ad for the Wool Bureau, which sent him to Australia in 1972 with a new model named Lisa Taylor. “By the time we hit Australia, we were very good friends,” he says, cocking an eyebrow. Not only that, but the pictures turned out well, too, and Strongwater’s career took off. “I was very naïve until that point,” he says. “I believed in Reefer Madness. If you took drugs, you were doomed. Unfortunately I found out that wasn’t true.”

The years 1978 to 1982 were “a zenith,” Strongwater continues. “We couldn’t get through a shoot without a major amount of drugs. People dropped coke on the table; they smoked joints. It was accepted. It was heaven. If you were bored, you called for a go-see. We fucked a lot, took a lot of drugs, and worked a lot. I’m sure the agencies knew about it. I was less than circumspect. But I never had one agent say a model couldn’t come here because this was an unhealthy place to be.” Finally Strongwater “realized drugs were damaging me,” he says. “I moved away, went into rehab, and came back in ’87. The party was still going on, but I wasn’t part of it anymore. People say, ‘Are you sad?’ No. I had the time of my life.”

Matthew Rich came to New York in 1977 and fell in with the Halston crowd at Studio 54. “It was my idea of heaven,” says the public relations consultant, who asks to be described as “one of the survivors.” Rich longed for a male model he’d seen in GQ magazine named Joe Macdonald. They soon met at Studio, “and we ended up necking in the balcony,” Rich says. They also sniffed coke, “and my heart was already going a mile a minute. That was it. We became almost live-in lovers.”

They hung out with Andy Warhol, Truman Capote, Liza Minnelli, Calvin Klein, and Halston—“all my godheads,” Rich says. “Andy drew Joe, drew his penis.” Macdonald became interested in art and started collecting photographs. But that and his growing taste for cocaine diverted him from his trade. “He alienated people,” says Rich. “He was temperamental.”

Macdonald bounced between Zoli and Ford. “Don’t call me anymore if you’re going to send me on bullshit,” he’d yell at his booker. Macdonald was the first male supermodel, and many opportunities were available to him—in play as well as work. “After three years he decided to sleep with every man who ever lived,” Rich says. People started whispering to Rich that “Mary,” as Macdonald was known, was hanging out at gay bathhouses. Rich and he broke up. Within two years Macdonald was dead of AIDS.

Rich went to work for Studio 54’s PR man and got a close-up view of the action there. “The big models were all there with their tops off—male and female—demigods. They were a draw, so they were protected,” Rich says. “Steve [Rubell] protected the people he liked. Aspiring models may have gotten a little used.”

Everyone was using drugs. “It got to the point where if you wanted to fuck a model, you had to have coke or Quaaludes,” says Alex Chatelain. “I’d fuck girls at Studio 54. To have a ’lude made it quite easy. But I wasn’t a club person, and I didn’t like drugs, so I didn’t do it that much.” One night Matthew Rich watched a model spy a rolled-up $100 bill between some cushions on a sofa in Studio’s celebrities-only basement. “She unrolled it, snorted it, licked it, and then threw it on the ground, having gotten what she wanted,” Rich says. “I snapped it up and bought more dust.”

The snorting, like the hustling busboys downstairs, who serviced the mostly gay Studio in crowd, were kept an inside secret for many years—even from insiders. Vogue’s Polly Mellen saw what was going on in the club’s balcony, though. “Two boys going at it, two girls, a girl and a boy. I saw every stage of something going on, and that scared me.” It was the same at Halston’s house. “Heavy drugs,” says Mellen. “I came, I saw, I left.”

When Kay Mitchell first met freckle-faced sixteen-year-old Patti Hansen at a Wilhelmina party in 1973, “she was very shy,” the booker says. “You couldn’t get her to talk, but there was something in her pictures.” Mitchell sent her to Seventeen, and Hansen spent the next two years “leaping and running and jumping” for the young women’s magazine. Then Glamour booked her and gave her a new look. “She was the epitome of the healthy teenager,” Mitchell says. “The product people all jumped on board and she just took off.” Hansen dropped out of school and moved into 300 East Thirty-fourth Street, the same building where Bruce Cooper later stashed his girlfriend.

Patti Hansen photographed by Charles Tracy for Calvin Klein Jeans

Patti Hansen by Charles Tracy, courtesy Staley-Wise Gallery, New York

In the summer of 1974 Hansen went to Europe, where she signed with Elite. “She’s basically fearless,” Mitchell says, “and that part of her personality gave her the impetus to forge ahead. She did intense, strong pictures there, came back to America, we sent them to Vogue and they saw a whole different person.” In 1976 Hansen became one of the magazine’s stars. In 1978 she appeared on the cover of Esquire, representing “The Year of the Lusty Woman.”

Hansen’s model friend Shaun Casey played ingenue parts longer. She lived in New York with her fiancé, real estate heir Martin Raynes, and caught the last good days of El Morocco and Le Club. It wasn’t until 1977 that she went to Paris and grew up. Hairdresser John Sahag cut her hair off and bleached the gamin’s cap that remained white. Paris Planning’s Gérald Marie took one look at her and decided to make her a star. Helmut Newton put her on the cover of French Vogue. Six weeks later she returned to America. “My bookings were off the charts,” she says. “I had five a day to choose from.”

Casey signed with Estée Lauder and joined the scene at Studio 54. “It was champagne, coke, uppers, downers, poppers, all that,” she says. “Everybody was doing drugs at that point.” She married Roger Wilson, of New Orleans, whose father had coowned an oil services company. Both his parents had died when he was a teenager, leaving him with a fortune of several million dollars. Though he liked Studio 54, too, “we didn’t dive in headfirst,” Casey says. “I worked every day. I’d do bookings at night. I was into making money and putting it away.”

It went on like that until 1983, when Casey’s Lauder contract and her marriage both ended. Lauder, which had always stuck with its faces for years, had grown more fickle. It replaced Casey with Willow Bay, who gave way in a few years to the more international Paulina Porizkova. Casey’s husband, Roger Wilson, “didn’t want to be married,” Casey says. “He wanted to be a playboy.” Then, that August, Casey’s younger sister, Katie, who was also a model, died of a drug overdose. Overwhelmed, Casey drank, stayed out late, and canceled bookings. “I think I canceled one hundred forty with Lord & Taylor alone,” she says. “I wasn’t partying. I was an absolute mess. So I changed my life. I married a guy who didn’t drink, moved to Florida, got a contract with Burdine’s, had a baby, chose my friends wisely, did my work, and went home. If you had money, you could do anything, and if you weren’t grounded, you could drown so easily.”

Casey’s best friend, Patti Hansen, had a wilder reputation. “She didn’t really have boyfriends,” Kay Mitchell says. “She had hair and makeup guys who liked to hang out and party, and Patti was their star. Gay guys. One of them said to me, ‘I’m looking for a man like Hansen.’ I said, ‘So’s everybody.’ She was big and strong. A photographer once came on to her, and she flipped him over her shoulder and knocked him out.”

Hansen would also “pull her shirt off if no one in the agency was paying attention to her,” says a Wilhelmina booker. Ever the athlete, on a shoot with Peter Strongwater at Lake Mohonk, in upstate New York, “Patti dropped acid and went rowing,” Strongwater says. Sometime later she went to Mexico City for a catalog shoot with Jerry Hall and photographer Guy Le Baube. “We went to the plane with a bus and a mariachi band to welcome Patti and Jerry and Bryan Ferry,” Le Baube recalls. “Patti got off the plane wearing transparent plastic shorts with no underwear and spike heels. She was literally steaming and showing Mexico City she was a real redhead.”

Hansen was resilient. “She could drink a bottle of Jack Daniel’s and look perfectly normal,” says a photographer she got high with. “The key to Patti was her ability to absorb drugs without losing control. What would floor another person wouldn’t bother her. She never missed a booking. She was never out of control.”

In 1979 Hansen met her match in Rolling Stones guitarist Keith Richard. “He became part of her energy instead of her becoming part of his,” says Shaun Casey. “She pulled him up.” But not without worrying her friends first. After they were introduced by Jerry Hall, Hansen disappeared for several days. “She got very, very, very skinny,” says Kay Mitchell. “Her hours turned around. He stayed up all night and slept all day, and she did, too. But for me that behavior, whether it was cocaine or tossing back drinks, was the aberration. She saved one of the great rock stars of our time. She was goodness personified, and I’m really not putting a pretty face on it. Doing the job and making everyone else look good because she showed up was the norm for Patti Hansen.”

Not so for Gia Carangi, a bisexual drug addict whose brief rise, long fall, and final death from AIDS were the subject of a book, Thing of Beauty, that infuriated models, who say she was hardly representative. “Gia walked in and walked out,” says Mitchell, who booked her as well. “The difference between her and models like Patti or Shaun Casey is that they worked for years. They’d go anywhere and do anything for work.”

For a moment Gia was a star, though, working with all the best photographers. She and Joe Macdonald bought their coke from the same Colombian on Fiftieth Street. “Joe would go off to the baths after we scored,” Matthew Rich says. “Gia and I would go out. I loved my Gia. She was adorable and sweet and loved to get fucked up the ass with fingers, and that horrified me, so she talked about it more. We loved to spell our names out on a mirror in coke.” Gia would get mad because Matthew’s name was so much longer than hers.

“Gia was a real mess,” says Bill Weinberg. “A trashy little street kid, not unlike Janice Dickinson. If she didn’t feel like doing a booking, she didn’t show up.” Gia hit quickly after arriving in New York. “She was about melancholy and darkness, and that made great pictures,” says a fellow model. But it didn’t make Gia any happier. At a shoot for Vogue she stumbled out of the dressing room in a Galanos gown, collapsed in a chair, and nodded out, blood streaming down her arm, right in front of Polly Mellen. Weinberg told Francesco Scavullo that Gia had become unreliable, but the photographer insisted she’d show up if she knew the booking was with him. Gia always showed up for him. “Frank called up raving and screaming,” Weinberg recalls wryly. Gia never arrived. “She would have been a casualty in any life,” says John Warren. After several comeback attempts Gia fell out of modeling and died in 1986.

Lisa Taylor never wanted to be a model. She thought the job was prissy and stupid. But the daughter of a J.P. Stevens executive from Oyster Bay, Long Island, did it anyway, to earn extra money while she studied dance. A friend who was a model brought her to Ford. “It was so easy,” Taylor says. “I walked in and started working.” She won her first cover, on Mademoiselle, at nineteen. Three years later, in 1974, she met Vogue’s Polly Mellen and became a star.

Eileen Ford introduced Taylor to her off-and-on boyfriend for the next decade, producer Robert Evans. “He was getting divorced, and he saw someone he wanted to meet, and he asked his friend,” she says. “I know there was something going on with Eileen and Bob and people like him, but I thought I was more special for Bob.”

Unfortunately Evans was often in California. That left a lot of nights free, and soon Taylor filled them with drinking and drugs. “I didn’t have too much self-esteem,” she says. “I was a prime suspect. I was partying, Studio 54, the whole number. Everyone our age was doing it.”

Taylor says she began to hate being touched and prodded by stylists and had paranoid visions of being in the center of a crowd of thousands, all trying to take her picture. “When you have a certain number of pictures taken of you, you feel robbed,” she says. “I felt I was giving, giving, giving and getting nothing back. Drugs made it a lot easier to sit there and look dumb in front of the camera. Modeling isn’t the most inspiring, intellectual thing to do. At the beginning the money and traveling were fun, but it gets tired very quickly. Me, me, me. I, I, I.”

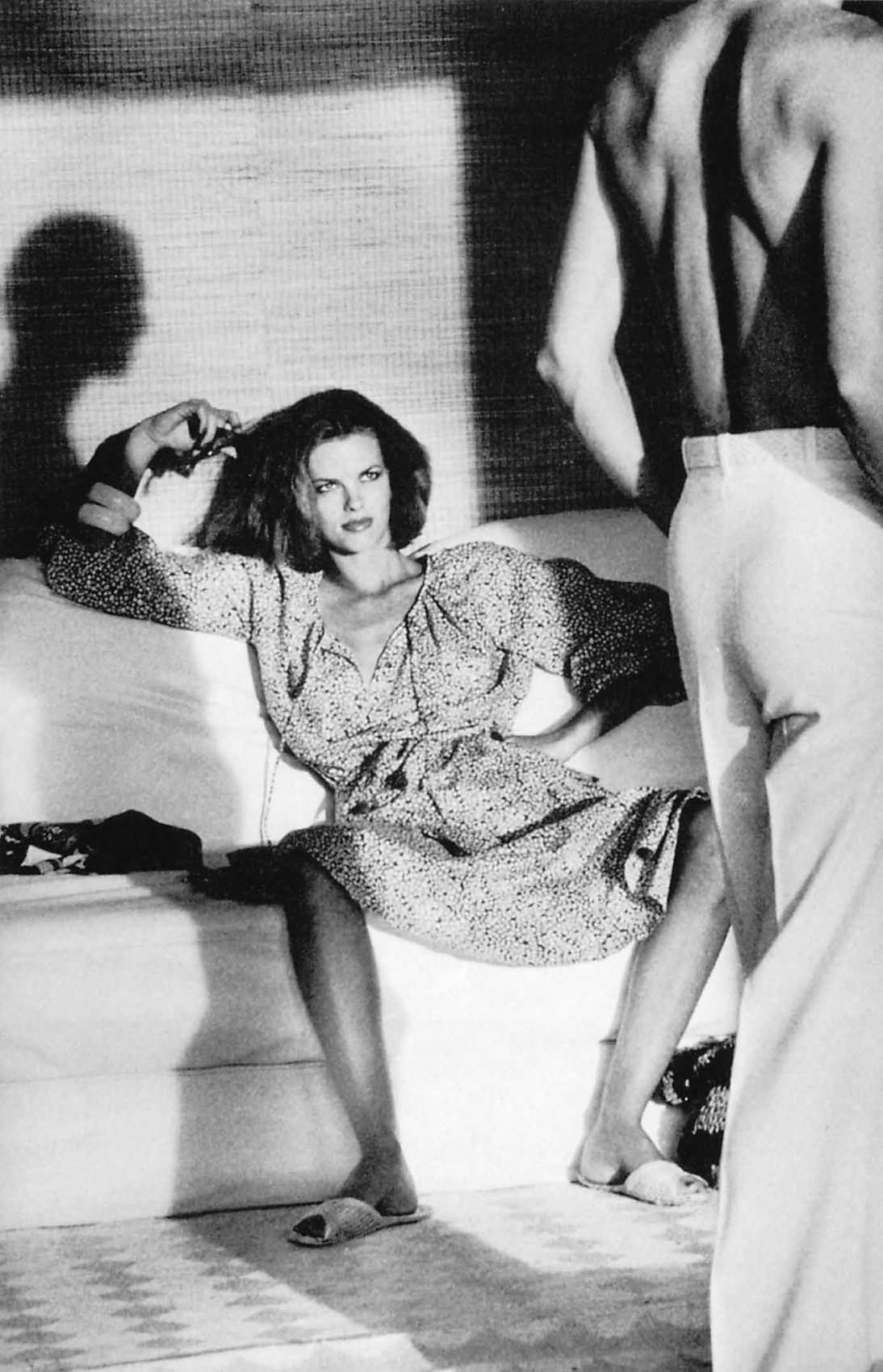

Lisa Taylor photographed by Helmut Newton in 1975

Lisa Taylor by Helmut Newton

Unlike some of her peers, Taylor says she kept her fun and games limited to the evening hours. “I was very professional,” she says. “And the more weight you lose, the more they love you. It was not a healthy job.”

In 1976 Taylor met actor Tommy Lee Jones on the set of a film about a fashion photographer, The Eyes of Laura Mars. She abruptly moved to California, informing Ford with a letter. “I wasn’t very communicative in those days,” Taylor says. A few years later she decided Jones was too possessive and returned to New York. That’s when she started seeing Cheryl Tiegs’s ex, Stan Dragoti. He didn’t make much of an impression either. “He was the next person for me,” she says. “Someone I dated. It wasn’t a great love affair.”

In 1981 the behavior of models and photographers finally started making the papers. New York magazine’s Anthony Haden-Guest wrote an article, “The Spoiled Supermodels”; the Daily News ran a series of profiles subtitled “The Dark Side of Modeling.” Taylor was featured in the first installment, “A Top Model’s Struggle Back from ‘Rock Bottom.’” She admitted her drug problems in often painful detail. “I was finally beginning to see the light,” she says. “I was seeing friends on covers whose eyes were dead on drugs. It was the end of modeling and the beginning of my life.” She moved back to California, joined Al-Anon, and began doing charity work. She married in 1989 and had twins in 1993.

“I had grown up at last,” she says. “Not that it’s their job, but the business, particularly the agents, could have helped more. Someone should have said, ‘Slow down.’ Instead they said, ‘Look at the money.’ You’re innocent and naïve, and they don’t want you to grow up. When I realized my life was more important than money, I left the business.”

Despite the Ford agency’s image, one rival booker says there were drug problems there, too. “Ford is extremely tolerant,” said a friend of Taylor’s at Wilhelmina. “Nobody ever said to Lisa, ‘You moron.’ Lisa was screaming for help, but people are afraid to speak up because the girl is going to pack up her vouchers and walk.”

Eileen Ford wasn’t the only one seeing no evil. A European model hit New York for a Vogue booking, collapsed on the set, and was rushed to a doctor who said she was so stoned her gag reflex was suppressed. “Vogue wasn’t concerned,” Wilhelmina’s Weinberg says. “All they wanted to know was, Would she be able to work the next day?” Grace Mirabella, Vogue’s editor then, sees it differently. “You don’t have time to wait,” she says. “Long stories don’t matter. When push comes to shove, what you care about is whether you have a picture.”

Esme Marshall may be the only model whose personal problems ever led to the creation of a new agency. The daughter of a former Chanel model, Marshall was a seventeen-year-old salesgirl in a department store in Cambridge, Massachusetts, when she was discovered by a fashion editor at Mademoiselle. That fall Marshall moved to New York, joined Elite, and took up modeling full-time. She fitted Elite’s new image precisely. “The style of girls had changed,” says booker Gara Morse, who’d left Wilhelmina for Elite’s new faces division. “It went from midwestern blondes to darker girls with crooked teeth. They weren’t ordinary. The nuttier the girl, the more John liked it.” Morse was given a free apartment on the East Side in exchange for playing chaperone to a revolving cast of eight aspirants who were crowded into another apartment next door. “I got what I was paid for,” she says. “If a girl wasn’t there, I had to go out looking for her.”

The night after her first job, Esme was at Studio 54, where she met Calvin Klein, who immediately booked her for an ad for his new line of designer blue jeans. The bushy-browed brunette’s career was launched. Soon thereafter she met Alan Finkelstein. The owner of a Madison Avenue boutique called Insport, he was a long-haired New York night bird, ten years her senior. They soon moved into a Greenwich Village duplex together. By 1980 she was one of modeling’s superstars, earning $2,000 a day.

Bernadette Marchiano, the then-estranged wife of sportscaster Sal Marchiano, was Esme’s booker at Elite. “Esme and I became fast friends,” she says. But Finkelstein got in the way. “He told me what Esme should be doing,” Marchiano recalls. “She was a child with no self-esteem, and this guy dazzled her.”

Finkelstein thought that Elite had gotten too big and that John Casablancas wasn’t paying enough attention to Esme. But Monique Pillard says the model wouldn’t listen to advice from her agency. “She never wanted to hear anything,” Pillard says. “She was telling us what to do. She was mixed up with drugs, everyone knew, but at the time you turned the other way when you had a very big model. I saw a lot. A lot. But I didn’t understand. If I’d been in that circle and done it, I might have understood more. It took me a long time to realize.” Finally a male model, Jack Scalia, “came in one day and told me all about drugs,” Pillard says. “I was so straight, and suddenly I felt very stupid. After that I’d say to girls, ‘Do you do drugs?’ And I got a lot of ‘Will you help me?’ But let’s face it, when you’re seventeen, you fuck around, and you don’t tell your mother.”

Finkelstein suggested to Bernadette Marchiano that she form a new agency, backed by a friend of his, a record label owner and producer named Jerry Masucci. It would handle just stars, and the first would be Esme. Marchiano liked the idea and spoke to a friend who also worked at Elite, Eleanor Stinson, about joining them. In June 1980 they formed their new agency. They called it Fame Ltd.

“Our approach was to treat models as businesswomen and not as pieces of ass,” Marchiano says. “There were no men in the agency. It was women working for women.”

The model wars were still raging. That month Ford signed up Lisa Taylor (who’d come back from Elite), Christie Brinkley (from Zoli), and Beverly Johnson (from Wilhelmina). Brinkley was actually suing Elite, as was Opium perfume model Anna Anderson, who’d left the agency and was demanding an accounting of her earnings. But the news wasn’t all bad for John Casablancas. Within a month Johnson left Ford for Elite. The same day Wilhelmina’s Patti Hansen joined Elite, too.

Almost immediately after Fame Ltd. opened its doors, it was revealed that the new agency had a silent partner: Ford, which owned a third of the agency in exchange for guaranteeing its vouchers. “Alan Finkelstein came to me and said Esme, Eleanor, and Bernadette were unhappy and wanted to start their own agency,” says Joey Hunter, a Ford executive.

Born Joe Pantano in Brooklyn, Hunter, a former doo-wop singer and actor, had a successful career as a Ford model throughout the sixties. “He was Mr. Seventeen, the cutest clean-cut guy in the world,” says Jeff Blynn, who modeled with him. After appearing in an off-Broadway flop in 1969, Hunter asked Jerry Ford for a job. He became Ford’s assistant and rose to second-in-command of Ford’s men’s division. Hunter’s involvement in modeling extended to his private life. After his first marriage, to an actress, failed, he married the socialite/Ford model now known as Nina Griscom Baker. They broke up within a year, and Hunter took up with Elite’s Debbie Dickinson. Hunter’s third wife, Kim Charlton, was also an Elite model.

Hunter and Richard Talmadge, one of the Fords’ lawyers and a music business investor, arranged the meeting between Jerry Ford and Masucci. They agreed to do the same thing Elite had done in Paris with its second agency, Viva, and open an independent editorially oriented boutique agency. Stinson and Marchiano got 5 percent each. Talmadge got 10 percent and was named a director. Masucci owned the remainder of the stock. “It was an opportunity for us to get two great bookers who had control of a couple models,” Hunter says. They hoped that Kelly Emberg and Nancy Donahue would follow Esme to Fame. It was also a chance to see if John Casablancas could take what he’d been dishing out.

No surprise, Casablancas wasn’t happy about this arrangement. Between them Bernadette and Eleanor “had every phone number, contact with every girl. It was the scariest moment I ever had,” he says. “So I said to the models, ‘If you stay with this agency, there’s a bonus. One percent less every year you stay with us.’ Some years later I had to write a letter to people like Paulina and Carol Alt saying, ‘I can’t do this. I can’t have you under a certain percentage.’” He’d won the battle, but the war wasn’t over. “I will never sleep with both eyes closed as long as that woman is around,” he said at the time of Eileen Ford.

Alex Chatelain was one of the first photographers to shoot Esme. “I believed in her,” he says. “She was wonderful.” But he thought Finkelstein was a bad influence on her. “The drugs were so out in the open,” he says. “Finkelstein was friends with everyone who was in. If they were famous, he was with them. Esme was in love with him. He took her everywhere, and you’d see her getting hyper and thinner, and at a certain point I couldn’t use her anymore. She was too thin. Finkelstein had destroyed her.” Esme dismissed published reports that she and her lover were cocaine users as ridiculous. “A lot of people like to blow things out of proportion,” she said.

Fame signed a few more good models, including Terri May and Nancy Decker, but it was short-lived. The first sign of trouble came when Alan Finkelstein called the booking desk, demanding that Marchiano cancel one of Esme’s bookings. If she didn’t, Finkelstein threatened, he would go to Albert Watson’s studio and drag her out. “Watson stopped the shoot and let her go,” Marchiano remembers. Then Finkelstein called back. “I was just playing with you,” he said.

“Fuck you,” Marchiano replied, hanging up. Their relationship went downhill from there. “It was beyond my control,” Esme said later. “He used to not let me go to bookings. It was very weird. He tried to run me over once. He was jealous of my booker ‘controlling’ me.” Though Finkelstein had promised he wouldn’t try to play agent, “he threw a monkey wrench in for no reason,” Marchiano says. “We’d have battles, battles, battles. Boyfriends are the major flaw in the modeling business. I wouldn’t talk to boyfriends. Ninety-nine percent of the time it was a problem. My problem was Esme’s boyfriend. Someone else had control. Alan didn’t want that.”

Finally, early in 1981, Finkelstein took Esme from Fame to Ford. According to an $8 million lawsuit Marchiano and Stinson later filed against their partners, Joe Hunter assumed the presidency of Fame at that time. “We stayed around awhile, booking the other models,” Marchiano says. But one morning in late May she arrived to find the locks changed and Fame’s books, records, furniture, and models all moved to Ford. Hunter told them they’d henceforth be working for the Fords. Less than two weeks later they were fired. Two days after that Fame Ltd. was formally dissolved.

“What happened was, the money went out of control,” says Hunter, who claims that Marchiano and Stinson were spending without consulting Masucci. “Jerry got disenchanted,” Hunter claims. “We felt we had a runaway ship financially, and we decided enough is enough. We did lock them out, and we bought Masucci out over a period of a couple of years.” In response to the bookers’ lawsuit (which was prepared by Elite’s lawyer, Ira Levinson), Jerry Ford said they’d been dismissed for incompetence and dereliction of duty and claimed that Fame was insolvent.

Marchiano categorically denies that Fame was losing money. In fact, she says, it had just started turning a profit when Ford closed it down. “There was no financial reason to close it,” Marchiano says. “I finally decided it was a whim of Alan’s.” She turned down Hunter’s offer to work at Ford and instead went back to work for Casablancas, who was starting a chain of franchised modeling schools with his brother, Fernando. Stinson moved to Miami, where she still works as a modeling agent. Their lawsuit against the Fords, Hunter, and Masucci was eventually abandoned. A suit the Fords subsequently filed against Ira Levinson for defamation was decided in Levinson’s favor.

At Ford Esme remained erratic. “She was always out, and you’d never know whether she would get to her booking or not,” Joe Hunter later said. In the Daily News series published in April 1980, unnamed sources referred to the twenty-year-old as “a burn-out” and “sort of gone.” It was said she’d stopped taking location trips, canceled bookings, turned up late, cried on sets, lost weight, and lost her luster. Elite was promoting a new model, Julie Wolfe, who was an Esme look-alike. Chain-smoking Marlboros, Esme denied it all, saying she lost weight because she was hyperactive. “I really don’t care what the fashion industry thinks,” she said. “They have a warped perspective anyway.”

Janice Dickinson later told writer (and ex-model) Lynn Snowden that the problem wasn’t drugs. Finkelstein was beating Esme up. “She was covered in bruises and didn’t want people to see her like that,” Dickinson said. “Esme was getting the shit kicked out of her. She just entered into this Svengali relationship.” Once she even showed up at Marchiano’s door bleeding. “He abused her,” Marchiano confirms. “She was physically abused and controlled.”

Finally, Esme told Snowden, she manipulated Finkelstein into throwing her out. Even then he kept victimizing her. “I just signed everything over to him,” Esme said, including property she’d bought in Colorado. She ended up owing $350,000 in back taxes. Esme retired from modeling in 1985, married a professional volleyball player, moved to France, had a baby, divorced, and launched a brief comeback in 1990. Friends say she’s since moved to California. Finkelstein lives there, too. He resurfaced in 1992, running a supper club called the Monkey Bar, part owned by his best friend, Jack Nicholson.

Nicholson’s friend Zoli kept a diary for the last five years of his life. Though there is scarcely anything written in it, a few sketchy passages offer a glimpse of his life and thoughts. On September 8, 1977, he and an “R. H.” attended an Irving Penn opening at the Marlborough Gallery and “saw I. Penn, L. Hutton, the Fords, Karen Bjornsen, Tim and Joe Macdonald, Mrs. V.” They went on to Julie Britt’s birthday party for model Peter Keating, where they saw Patti Hansen, Patti Oja, Janice Dickinson, and Lisa Cooper. “Home with R. H.,” the entry concludes. “HANGover.”

On September 8 Zoli picked up his mother, who’d been diagnosed with cancer, at the hospital. “She’s doing fine.” An entry about falling in love with R. H. follows. “It’s the only thing that I can’t count on like my job, my house, my family, my friends and yet in that uncountability [sic] I feel more stable than in all those other temporary securities.” That October Zoli noted his plan to move from the town house to 955 Lexington Avenue. “It’ll be fun to live alone and somewhat strange,” he wrote. Not long after Zoli and his partner, Bennie Chavez, began to have differences over money.

Chavez says, “There were people in his life who were rather unsavory. A couple of his lovers were great sources of trouble, asking why I should have half the business. The problem was, we had a written agreement.” Then Chavez fell in love with an Englishman and decided to marry him. Zoli felt sure she was making a mistake. The next entry in Zoli’s diary are notes headed “CHAMELEON.” After a scientific description of lizards Zoli added, “also a changeable and fickle person.”

Zoli was having a crisis. “I thought the solution would be to move from this house, this beautiful house inhabited by ghosts, namely me, mutti [his mother] & B. C. [Chavez],” he wrote. “The next minute, it was to change professions completely as work seems to be a compote of self-indulgent, greedy, ungrateful, egotistical narcissists…. I’ve arrived somewhere and stayed too long.” That Christmas he went to Aspen and saw ex-model and designer Jackie Rogers, François de Menil, and Jack Nicholson. “What a blasé, spoiled man I am,” he wrote. “How well I seem to have it, but if I could only get some real enthusiasm for anything I would be most pleased. I am learning to resign myself, to accept reality in people without rose-colored glasses…. It’s no fireworks for me. I’m probably better off for it. But I yearn for the passions of the moment and also want to pass my life in insanity and recklessness which I repress for the sake of? what I don’t know.”

There are no more diary entries for six months until Zoli notes a July 1978 sailboat trip to the Virgin Islands with a man named Bob. “Both quit smoking and eating meat, a changing time,” Zoli noted. When he got back, it was time to split up with Bennie Chavez. The next few pages were filled with angry ideas on how to separate their business. “A lawyer convinced him he should get tough, and he took me to court,” Chavez says.

Zoli’s diary picks up again many blank pages later, with the 1981 notation “My dear sweet mama died on April 16 at 1 A.M.” Again many pages intervene, and then in the very back of the book are three more entries. The first two are lists of Zoli’s stock holdings late in 1980 and in mid-1981, when they totaled almost $145,000. The last entry in the diary appears to be the beginning of a screenplay. Two men meet in a dark gay bar. A young executive type picks up an older man, takes him home, and they have sex. Then the man reveals “he’s a vampire,” Zoli writes. “Vampire is … 30 going on 300. Likes boy and confides that he is tired of being a vampire….”

By all accounts, Zoli was only a voyeur at the party that fascinated him so and was in certain ways quite bourgeois. He was never promiscuous, according to his friends. He had boyfriends and “lived with them,” says Barbara Lantz, who now co-owns Zoli with Vickie Pribble. “He was very relationshiporiented. In one case, Zoli’s mother lived with them and Zoli moved out and the guy kept living with [Zoli’s] mother.”

But not long after his mother died, Zoli started feeling ill. “He had the weirdest symptoms,” Lantz recalls. “He went to forty doctors all over the country for tests. Joe Macdonald had already been diagnosed with AIDS. Zoli had an AIDS test, and it came back negative.” He went to clinics and gurus and even hooked himself up to a biofeedback machine. On one of his trips he visited ex-Wagner model Geraldine Clark in California. “I got very frightened when I saw him,” she says. “He was thin as a stick and had a high fever.” He cried while they were having dinner. In September 1981, Zoli’s sister says, his doctors diagnosed lung cancer. “We thought he was being melancholy,” says Lantz. “He had a tendency.” He’d lost his case against Chavez, and they’d finally split their holdings. She kept the town house; he got the agency.

In November 1982 Zoli checked into the hospital. He had his doctors tell his employees he had tuberculosis and would be all right. Bennie Chavez knew differently. “I saw him on the street a few days before he went into the hospital,” she says. “He was very thin; he had no voice. He had a look of peace in his eyes. It was almost hypnotic, and it disturbed me.” Geraldine Clark flew to New York to nurse him. The cancer had spread to his esophagus, and the radiation treatments that doctors prescribed caused his food and air pipes to fuse together. Clark prepared food in a blender for her friend. That was the only way he could eat. Finally, the day before he died, Zoli sent his sister back to her home in Virginia and Clark back to California. “He knew there was the possibility he had AIDS,” Clark says. “He had one lover who’d been very promiscuous. He’d become like a pariah. No one wanted to touch him. I was terrified, but before I left, I pushed the pipe away and kissed his lips. It was the first time he’d smiled in days.”

Finally Zoli succumbed. He was forty-one. To this day his friends and family aren’t sure what really caused his death, though they note that his last boyfriend later died of AIDS. “There are no records saying it was anything but cancer,” says Lantz. “It certainly sounds like AIDS. But there was never a diagnosis.”

The day Zoli died, the word went out among the models, but they were asked to keep his death a secret. A quiet memorial was scheduled because Zoli wanted no fuss, and indeed, except for a brief notice in a photographic trade newspaper, his death was never publicly acknowledged. Meanwhile, Zoli’s lawyer called six key employees together. There were two wills, he told them. Only one was signed. Both split the agency among the employees, but in different ways. The minority shareholders wanted to sell. But Lantz and Pribble wanted to keep the agency going and did.

If there is such a thing as karma, Zoltan Rendessy’s stayed good to the very end. Shortly after Zoli died, John Casablancas and Wilhelmina’s Fran Rothschild both called and offered to lend the agency bookers, so the staff could attend the memorial service. Zoli’s most fitting epitaph may be what didn’t happen next.

“We didn’t lose a single model,” says Barbara Lantz.