“I’m not a morning person,” Christy Turlington said in apology as she strolled into Superstudio Industria, the fashion photo factory in New York’s Greenwich Village just after nine one frigid morning in December 1991. Turlington had been booked for a three-day job, posing for an Anne Klein ad campaign consisting of a dozen studied, glamorous black-and-white pictures by photographer Stephen Klein. Then twenty-three, she was chosen to exemplify classic American beauty. For doing that, she would earn about $60,000 in seventy-two hours. A sum well worth waking up for.

Stripping off a mustard-colored jacket, beige Italian jeans, a white shirt, a scarf, white socks, and black suede Chanel ballet flats, she tried on several outfits over a little lacy bra, white bikini panties, and thousands of goose bumps. Between changes, Garren, a hairstylist, gave her a blunt trim, and makeup whiz Kevyn Aucoin worked on her face, chattering about lipsticks, movies, and models. He did most of the talking. Turlington’s task was to sit still while others made her beautiful. Not that she was so bad to begin with. But three hours after she arrived in the studio, she’d blossomed, becoming, as Aucoin cooed in her ear, “the beauty of the earth.”

“Thanks, kid,” Christy said, brightening.

“I was gonna say the universe,” Aucoin went on.

Christy spun around in her chair, her feline eyes widening. “Bigger!” she shouted.

“Bigger!” Aucoin declared. “The most beautiful anything there is!”

Christy Turlington was at the top of her profession, one of that small, special band of young women known as the supermodels. Remote confections of cultured image and cherished dreams, she and colleagues like Cindy Crawford, Paulina Porizkova, Linda Evangelista, Naomi Campbell, Elaine Irwin, Tatjana Patitz, Yasmeen Ghauri, Karen Mulder, and Claudia Schiffer had come to epitomize modern beauty and grace. They seemed to be in charge of their lives and their careers.

They’d even remade the ideal of perfection. No longer was it necessary to have a belly like a washboard or skin as white as snow. While Irwin, Patitz, and Mulder all are classic blondes, more than half the supermodels, including Turlington, had dark hair. Some even had dark skin. Crawford has a mole near her lip; Campbell, a scar on her nose. Evangelista is scrawny; Schiffer is strapping.

Supermodels were rich in more than their fortuitous conjunctions of flesh and bone. Like Crawford, who’d become Revlon’s principal contract face, and Porizkova, who represented Estée Lauder, Turlington was an “image” model. She’d been the face of Calvin Klein’s Eternity fragrance since 1988 and had just signed a new contract to represent Maybelline cosmetics. As that company’s symbol Turlington was projected to earn about $800,000 a year for twelve days of work selling makeup. Escalators in her contract, governing geographic areas where her photos could be used, appearances in additional non-makeup assignments, and separate photo usage fees, created the potential for even more income. A million dollars a year was a lipstick trace away.

And that was peanuts compared to what companies had come to believe they could earn by using supermodels. The theory went that image leads to income. “It’s like buying a Gucci bag,” says Milanese model agent Marcella Galdi. “You show the world you have the money. Especially for an unknown company, you show the world that small as you are, you have the twenty thousand dollars.”

Turlington’s Maybelline contract was state-of-the-art. Despite the fortune being paid her, she was allowed to continue to work for magazines, for clothing companies like Anne Klein, Michael Kors, and Chanel, for Calvin Klein, who had her under contract as his Eternity fragrance model, and for any designer who could afford to send her stalking the runway in fashion’s seasonal selling rituals. Each of the elite young supermodels was regularly raking in anywhere from $3,000 to $10,000 per runway show. Turlington’s agents at Ford Models estimated her 1992 income at about $1.7 million. “We completely reinvented the whole money thing, we make a ridiculous amount of money,” Christy admits. But it is more than money that sets her apart from the mannequin pack.

Linda Evangelista in Versace couture, photographed by Dan Lecca

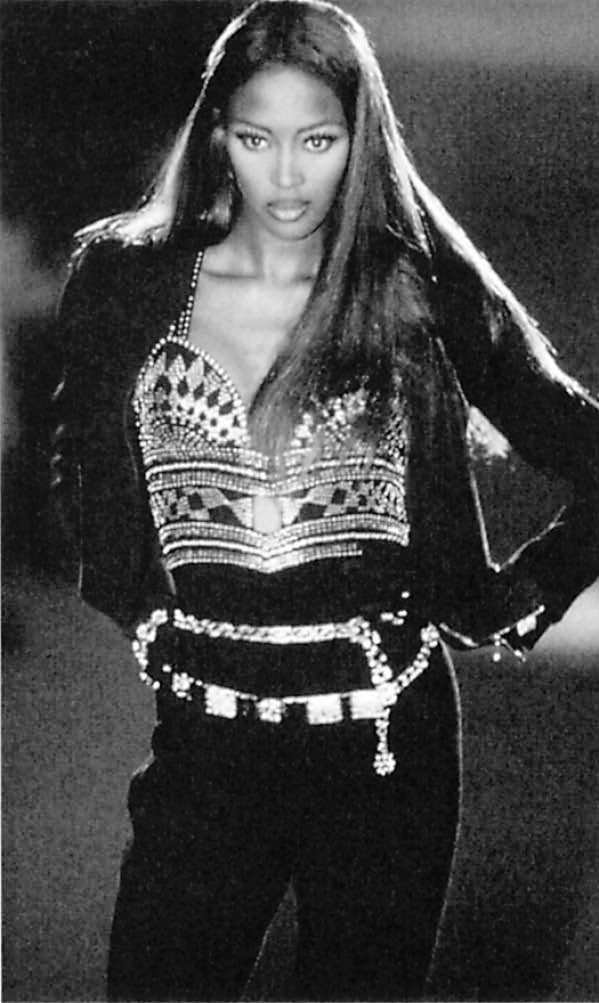

Naomi Campbell in Versace couture, photographed by Dan Lecca

Christy Turlington in Versace couture, photographed by Dan Lecca

“She’s a very rare girl,” says photographer Bruce Weber, who is best known for his Calvin Klein and Ralph Lauren ads. “She can give herself up totally to the situation, whereas a lot of girls say, ‘What’ll this picture do for me?’ Christy has done more great photos for little money than most models. Most of them are worried about how much they’ll make. She wants to be able to look back and say, ‘I did great work.’”

As Aucoin penciled and shaped Turlington’s pussycat eyes, Stephen Klein came into the dressing room and silently studied her, his basset hound eyes obscured behind blue-tinted sunglasses. Forty-five minutes were spent placing, then re-placing a birthmark, first beside her eye, then higher, then lower.

“Put it in my ear,” Christy said.

“I’ll put it on the tip of your tongue,” Aucoin threatened.

Finally, just before 1:00 P.M., Christy stepped before the camera for the first time. Klein shot a couple of Polaroids, then had Aucoin soften her makeup. Forty-five minutes later Klein finished his first shot and called a break for food. Turning up her nose at the catered health food lunch, Christy ordered from a Chinese menu. “Fried kitten paws?” Aucoin joked.

“Shish-ka-dog,” Christy said.

Before her food arrived, the team knocked off another shot, and Anne Klein’s then designer Louis Dell’Olio arrived, full of praise for his supermodel. A resolutely regular guy, he explained that Christy was right for all the wrong reasons. In an era when too many models had become as lofty as the Concordes they flew on, Christy was humble and down-to-earth. “She’s a real person,” Dell’Olio said. “No attitude. With models, when you get ’em in a group, they’re not sweet. But not with her. No matter what, she’s sweet.”

Born in 1969, Turlington grew up in a suburb of Oakland, California, the middle daughter of a Pan Am pilot and an ex-stewardess of Salvadoran extraction. The Turlingtons moved to Coral Gables, Florida, when Christy was ten years old. She never gave a thought to fashion. Her mother had to force her to look at Seventeen to spruce up her look. She was more interested in the horse her father bought her. She rode competitively, training every day after school at a local farm.

She was riding the day she was discovered by a local photographer. Dennie Cody was shooting photos of two of her schoolmates, aspiring actresses, when he spotted fourteen-year-old Christy and her older sister, Kelly. “Christy was sitting straight and tall in the saddle,” Cody says. “I knew right away. You don’t run across many girls you know can make it to the top.”

Christy was excited. But she already knew to play hard to get. Cody recalls her as “taken aback … reticent … skeptical.” A family meeting and several phone calls ensued. “I had a long talk with Christy’s mother,” Cody says. “I told her the only limitation would be her motivation.” Finally Elizabeth Turlington agreed and took her girls to Cody’s studio.

“He had a couple really sleazy pictures on the wall,” Christy says. “Some nudes. I was like, God!” But Cody’s wife worked with him, so Christy decided to go ahead. “He took ridiculous portraits with a lot of makeup. I was really quiet,” she says. “He was really positive I was going to be a star.” She wasn’t so sure. “I’d watched Paper Dolls on TV. I thought this is probably what they all say.” She had braces on her teeth and long, curly hair, and she’d always thought her sister was cuter, more outgoing, and more popular than she. Unfortunately Kelly was five feet six inches. Christy was five feet eight inches.

Cody told the Turlingtons about how model agencies worked, the big New York firms using local firms as feeders, the equivalent of baseball’s farm team system. “The only one I’d heard of was Ford,” Christy says, so she went to see Michele Pommier, an ex-model who was then associated with Ford.

“I said she was going to be a major star,” Pommier recalls. “They laughed. She was so shy. She didn’t know what was going on.” That changed soon enough. “My mom must’ve gotten excited,” Christy says. “She started buying me new clothes for testing. I wouldn’t imagine her making the investment just for the fun of it.”

Cody never saw the Turlingtons again. After a brief period of testing in 1983—making pictures with various local photographers—Christy put together a portfolio and a composite and began to earn back her mother’s investment, modeling after school for $60 a hour. Liz Turlington went everywhere with her daughter, “but she wasn’t a stage mom,” Pommier says. “I have mothers you could string up. She was just a doll. Always in the background, watching out.”

When the head of Karins, Ford’s associated agency in Paris, came to Miami, Pommier called Christy in, announced that of course, the big agencies would want her but then decided they couldn’t have her. “She’s not available,” Pommier said. “She’s too young. Maybe next summer.”

In 1984 Dwain Turlington had a heart attack and moved his family back to the San Francisco suburbs. Christy joined the Grimme agency. She took the BART subway system after school to model for Emporium Capwell, a local store chain. “For a hundred dollars an hour!” she says, laughing. “Which was great.”

Mostly she kept her career a secret from her schoolmates. But when she made the cover of the fashion section of the San Francisco Chronicle, “somebody passed it around in my French class,” she recalls. “The teacher grabbed it, made a big deal, ripped it up, and threw it away. I didn’t bring it to school! I never in any way brought it up or bragged about it. But I do remember taking advantage a couple of times when I wasn’t prepared for a careers class. ‘Shit, what can I use? Oh, I’ll use my career.’ I must have looked like such an idiot, passing my voucher book around.”

Karins invited Christy to go to Paris in 1984. Eileen and Jerry Ford came to San Francisco that spring, met Christy for the first time over breakfast in their hotel suite, and approved the plan. Her San Francisco agent was against it. “I never really liked Jimmy Grimme to begin with,” Christy says. “When he said, ‘I don’t think you’re ready to go to Paris, I think you should stay around here for a while,’ I was like, ‘What do you know? I already have an agent in Paris. I’m going.’”

That summer Christy and her mother went to Paris for a month, partly to test the waters and partly as a summer vacation. “I only worked a couple of times,” Christy remembers. “I tested a bit. We were in a little hotel. I remember seeing Linda’s pictures in French Vogue at that time. They were working, all of them.” Cindy Crawford was in Paris, as were Linda Evangelista and a teenage model, Stephanie Seymour. “She was there without her mother, and she was starting to see John Casablancas,” Christy says. “That’s what my mother was afraid of. I didn’t meet any slick people at all ‘cause I was with my mom.”

There was more than one pair of protective eyes watching the fifteen-year-old. When Eileen Ford arrived for the couture shows in July, she made a point of seeing Turlington and her mother and invited them to stop in New York for a week of testing on their way home to San Francisco. A rude surprise awaited Christy there. Ford didn’t remember telling her to come to New York. “I’m thinking, obviously she knows that I didn’t work, so she changed her mind,” Turlington says. “So my mom goes home, and I stay a week, and in that time I see all the magazines, Vogue, Mademoiselle, but then my grandmother passed away, so I went home.”

Turlington soon left her San Francisco agency. Like many top models who emerged in the eighties, she realized early on that she would have to run her own career. “I always thought Jimmy Grimme was small-time,” she says. “I mean, they have classes in his office to show how to do runway walking, and he used to say, ‘Walk as if you had a coin between your buns,’ and he’d do the old walk that was so ridiculously dramatic. He acted like he knew it all, and I knew that being in San Francisco, which isn’t the fashion capital of the world, he couldn’t.”

She’d met Gary Loftus, an American who’d worked at London’s Models One and Askew agencies before returning to San Francisco to open one of his own. “All the girls were with him,” Christy says, “and he was a really nice guy.” So she switched agencies; under her sweetness was steel. “I did it mostly to piss Jimmy Grimme off,” she says. “I hardly worked in San Francisco, so it really didn’t make a difference. And he was such a little snot. He complained to Eileen, but it was out of her hands.”

After modeling her way through her sophomore year in high school, Christy, sixteen, arrived in New York in summer 1985, moved into the Ford town house, and began making the rounds of magazines and photographers. On her last day in New York the model editor at Vogue saw her, liked her, and sent her to Arthur Elgort.

“It was July,” Kevyn Aucoin recalls. “A zillion degrees and no air conditioning. Girls sweating their makeup off before I could get it on. Christy was a real trouper. Excited, into it, and very sweet. I get very concerned about girls that young doing this shit. This business is full of people who’ll blow wind up your skirts and two weeks later don’t know you. But I could tell instantly—I mean, I hoped—she’d keep her sanity and get whatever she wanted.”

“It was very glamorous,” Christy says. “Arthur was shooting Cheryl Tiegs in this big, beautiful studio. They were drinking champagne, opera music was on, and he took a roll of film on me. I went downstairs and called my booker. She said I was already booked for a week. I was so excited. Vogue was a big deal. That made it legitimate.”

Christy went back to school in August, but Vogue kept calling. In October she was back in France to shoot the collections. She arrived at the Hôtel Crillon in Paris, where Polly Mellen, who was doubling as editor and chaperone, was staying, only to learn she’d arrived a week too early. “So I sat around for about five days,” she recalls. The fashion editor of French Vogue took her shopping. “And then we flew to Cannes to shoot with Dennis Piel, but I basically sat in a hotel room eating the whole time” because the team on the shoot seemed to prefer the two other models. Finally, on her last day in the south of France, Turlington got a chance to work. “And they were the two great pictures of the whole series,” she says.

The photographs appeared in December. Her school friends were blase. “I hung around with punk rock kids at home, wore black all the time, this totally antifashion thing,” she says. “What I was doing was totally ridiculous to my friends.” But it was incredibly exciting to her. “I was so naïve.” Christy moans. “I sent family Christmas cards to the editors I’d worked with. Like they were my new friends.”

It would be another year before Christy’s parents allowed her to move to New York on her own, but she was already a working model. She transferred to a professional school that would accommodate her frequent absences as she became a regular commuter between San Francisco and New York, always staying at Eileen Ford’s notoriously strict house-cum-model-dormitory. Ford insisted that Turlington stay until she turned eighteen. She still promoted herself as a paragon of virtue. “Who’s to teach these children values if we don’t?” she asked.

Christy sneaked out. “I was wired in that house,” she boasts. “I’d go out all the time, to Palladium, Area. I’d hide a T-shirt downstairs so that if Eileen woke up, I’d be able to say I couldn’t sleep and I’d gone downstairs to get a glass of milk. I knew every stair that creaked. I used to smoke and drink beer and champagne in my room.”

In December 1986 she quit school and moved into a loft in New York’s SoHo. It shared an entrance with one occupied by Eileen Ford’s daughter, Katie. “I had a suitcase of clothes, I got a little kitten, and Katie put a bed in my room,” Christy says. “That was all I had.” A few weeks later her parents arrived with sheets and a TV.

As Turlington was getting started as a model, the unprofessionals of Bitten Knudsen’s day were on their way out. “The girls are getting rich, so rich,” says fashion editor Polly Mellen, who recalls Kim Alexis casually saying that she was buying an $800,000 apartment. “Yeee gods!” says Mellen. “We’re getting into real stardom.”

In many ways Paulina Porizkova set the stage for Christy’s success. Paulina was born in 1965 in Prostejov, Czechoslovakia. Growing up, she never gave fashion a thought. “Are you kidding?” She laughs. “In Czechoslovakia?” But there was one fashion she wanted desperately: a Communist insignia. “I was dying to be a Pioneer,” she says. “Those are the ones wearing the little red scarves. You can’t become a Pioneer until fourth grade. I was in a pregroup. I was brainwashed. I was Red from my toes to my head.”

Her mother, a teenage secretary, and her father, a truck driver (who says Paulina was actually “kind of an anti-Communist, but a little punk, really”), split for Sweden on a motorbike during the 1968 Russian invasion of Czechoslovakia, leaving Paulina with a grandmother. When the Czechs threatened to put the child up for adoption, her mother returned, disguised, to rescue her. But on her way to rescue Paulina, she was arrested for speeding, and her true identity was uncovered. Paulina’s mother spent the next six years in jail and under house arrest. Meanwhile in Sweden Paulina became a Cold War symbol. “Poor political little baby,” she says. “Pictures of me hugging my teddy bears saying, ‘I want to see my mummy and daddy.’”

Paulina Porizkova photographed by Marco Glaviano

Finally the Porizkovas were expelled from Czechoslovakia. “We were too famous to just bump off,” Paulina believes. “Our aunt and her husband took us to the border of Austria. There was this long, tall figure: my father, who I basically didn’t know. Unbelievable, you know?” Paulina’s voice quavers as her story continues. Her father no longer comes up. “I had an awful time because I was a famous political refugee,” she says. “I felt terribly sad and everybody told me how ugly I was and my mother was having a nervous breakdown.”

Together with a friend who dreamed of being a photographer, Paulina escaped into fantasy. “We copied Estée Lauder ads. We would put me in the foreground and a vase with some old flowers in it and shoot it with a Kodak Instamatic.” Her girlfriend sent their photos to a modeling school owner who took Paulina to Copenhagen to see John Casablancas. A month later, in 1980, she was an Elite model in Paris. “It was the biggest whack of freedom I ever got.” she says. She wore her TOO DRUNK TO FUCK T-shirt out dancing at night and got up every morning and worked. “When you’re fifteen, that’s not a problem,” she says.

Neither were the other perks that come to teenage models. “You’re going to have these old guys knocking down your door and offering you coke. I never … it just wasn’t my part of life.” Being a sex symbol was, though. “I didn’t care whether I was known as a face or a body or both,” she says. “I couldn’t care less as long as it gave me more work and more money. That was just fine with me.”

Janice Dickinson had broken the mold. Now Paulina became the first nonblond supermodel. She arrived on the scene just as Elle magazine—newly published in America—began regularly running spreads that featured a multiethnic cast. Advertisers like Benetton were starting to do the same. In 1986 Monique Pillard proposed to Paulina that she pose for a pinup calendar.

The Paulina calendar grew out of Pillard’s frustration with Sports Illustrated’s bathing suit issue. Editor Jule Campbell used a lot of Elite models, including Carol Alt, Kim Alexis, Christie Brinkley, and Paulina, but it wasn’t enough for Pillard. “I was always a little annoyed when Jule didn’t see potential and I did,” the agent says. In 1986 her close friend Marco Glaviano shot a Paulina calendar. It sold 250,000 copies. The next year the pair released a second Paulina calendar and the first Elite Superstars Swimsuit Calendar. Pillard also started booking her models for tasteful nude spreads in Playboy shot by trusted photographers like Glaviano and Herb Ritts. The pictures they produced were far more comprehensible than the images of Patou pouf skirts then prevalent in fashion magazines. “Monique understands what the public wants,” says John Casablancas. “And so she produced this kind of populist, sexy, nonfashiony image. And she just touched the right chord. She absolutely deserves credit.” Supermodels were here to stay.

The next year—1987—Christy’s career went into overdrive. Though she worked with top names like Herb Ritts, Patrick Demarchelier, and Irving Penn, the real source of her new power was her collaboration with the photographer of the moment: Steven Meisel. Meisel looks like a Jewish Cherokee, with thick, straight hair cascading to his shoulders past dark eyes that seem to have been kohled. He has worn only black since leaving high school: black boots, jeans, turtleneck, trench coat, and a do-rag bandanna under a black rabbit hat with flying fur earflaps.

Meisel and a pack of powerful fashion friends have tried to resurrect the cult of the fashion photographer of the sixties, with Steven, Naomi, Christy, and Linda playing updates of Bailey, Twiggy, the Shrimp, and Penelope Tree. Meisel has also been compared to the earlier avatar Avedon, whom he’s worshiped since grade school. At first Meisel’s work was slavishly imitative of and less intellectual than Avedon’s. But Meisel’s ambitions have always been different. And his vision is more in tune with this mass-media era than with Avedon’s temps perdu of an image aristocracy.

“I am a reflection of my times,” Meisel has said. More precisely he reflects the paucity of originality in a fashion culture that now slavishly celebrates the past. Meisel plunders and adapts from fashion’s memory, not from its collective unconscious. He copies everyone from Horst to Bourdin and poses his models as actresses and mannequins of earlier times. His postmodern samplings are all of a piece with the fin de siècle rag picking that has given humanity the AT&T Building and rap music.

Meisel’s unoriginality is an open industry secret. He’s considered a sort of rephotographer. “He does a very good job of systematically making a story out of other photographers’ styles,” says Bert Stern, who once threatened legal action over photographs of Madonna that Meisel copied from Stern’s famous 1962 “last sitting” with Marilyn Monroe. In France Jacques Bergaud, the owner of Pin-Up Studios, dismisses Meisel with the nickname Xerox.

Until he was about twenty-five, Meisel lived at home with his parents in Fresh Meadows, Queens—three blocks south of the Long Island Expressway. He was an indulged child who went with his mother to watch her get her hair done by Kenneth, and he started reading her fashion magazines in the fourth grade. They were his “escape mechanism,” he’s said. He even cut school—with his mother’s permission—to read them the day they were published. “I was obsessed with the magazines, absolutely,” Meisel says. “I was totally insane with it.” Cheerfully he admits that his interest was “a little peculiar.”

In the sixth grade he began using the names of known photographers to pester model agencies for composites. He had friends pose as messengers to get them. He collected them like baseball cards and recalls them with uncanny accuracy. “I had to know who the girls were. What their genius was,” he remembers. He lurked outside Richard Avedon’s studio in hopes of seeing models arrive. He cut school and hung out at boutiques. When Twiggy came to New York, he called her agency, put on a phony accent, said he had to change a lunch date with her and asked where she was. “Like fools, they [told me],” he says, smirking. Arriving at Melvin Sokolsky’s studio, he talked his way past Ali MacGraw and watched as Bert Stern filmed Sokolsky shooting the skinny cockney.

At the High School of Art and Design, Stevan (as he spelled his name) studied fashion illustration and was a member of the Chorus and the Senior Council of the class of 1971. He went on to Parsons School of Art but never graduated. “It was boring,” he says. After brief stints sketching for Halston and writing about fashion for New York Rocker, Meisel was hired as an illustrator by Women’s Wear Daily. “I adored him,” says his boss, James Spina. Meisel lived at home, “just like the Beaver in a garden apartment,” Spina, a neighbor, recalls. Meisel would drive Spina home in a Buick Scamp his father bought him to keep him off the subway. They went to concerts together and would pore through Meisel’s collection of old fashion magazines under the gaze of posters of Veruschka and Mott the Hoople.

Meisel was friends with two designers, Anna Sui, who went to Parsons with him, and Stephen Sprouse, whom Meisel met at a drag bar, the 82 Club, in 1974. Soft-spoken Sprouse, thirty-one, first drew clothes as an Indiana nine-year-old, met Norell and Geoffrey Beene at twelve, apprenticed with Blass, and dropped out of design school to work for Halston.

New York’s clubland years had begun and were to shape fashion, photography, and modeling for the next two decades. “The scene was very flamboyant,” says Deborah Marquit, a Parsons classmate who also got a job at WWD. “Everyone came to work crazy from the night before. All they talked about was sex with men.” Gabriel Rotello, a musician and night life impresario, met Meisel and Company at the Ninth Circle, a Village gay bar. Rotello, who went on to share a summer house with Richard Sohl, Meisel’s best friend from grade school, followed the group’s exploits for a decade. At first Sohl was the star. He was the beautiful piano player in the Patti Smith Group. Smith would introduce him onstage as “Richard D.N.V. Sohl.” The initials stood for Death in Venice.

“The whole thing was gay,” Rotello says. “Richard would entertain us with stories of them coming into the city from Queens in junior high and going to gay bars. They both had real wild streaks, wanting to be where the action was. You’d hear peals of laughter; that was Richard. Steven was very reticent, obviously very talented, very enigmatic. I thought he manufactured his eccentricities as he might an illustration. For effect.”

Meisel and Sohl shared a conspiratorial streak. They would whisper in a private language and call each other names—Sissy Meisel and Tanta Ricky. “If you didn’t know the codes, you wouldn’t know what they were talking about,” Rotello says. “Together I found them a little scary.” Teri Toye was scarier. Meisel met her at a party at Rotello’s loft, jumping on his old sofa and breaking it. “Teri Toye was totally fabulously insane, screamingly funny, and out of control,” Rotello says. “Holly Golightly in drag.” Born in Hollywood on an early sixties New Year’s Eve (“No one ever believes me,” she grouses), Teri was adopted and spent a spoiled, sheltered youth in Des Moines, Iowa. Her pale, freckled face is still open as the plains, when it’s not closed behind shades. “I was never really a boy,” she insists, “except for the one obvious thing, and that’s the only thing I ever changed. I didn’t change my sex. My sex changed me.”

In 1979 Teri moved to New York to study fashion design. The first year she registered as a boy, the second as a girl. “I think they were a little confused,” she says. Soon she visited school only to model for illustration classes taught two nights a week by Meisel. The pair made quite a statement. Teri’s lank blond image complemented Meisel’s smoldering Cleopatra pose. They made a pretty Odd Squad.

“We would get together at Sprouse’s for four or five days,” Teri recalls, “design clothes, have them made, put them on, and take pictures of ourselves. Then we’d wear them out at night with our friends.” They became fixtures on the after-hours scene, often in club bathrooms. “We love bathrooms,” Teri laughs. They would go to the Mudd Club in their pajamas and bragged of flooding the bathroom, “riding” the toilets in a motorcycle fantasy. They began sporting long, lank Dynel wigs and all-black clothes and dressed their friends in Day-Glo neon to stand out from their own in crowd.

The times were wilder than Meisel. Though many people around him were drinking and drugging and having sex obliviously, says Rotello, “Meisel always seemed a little too dignified to be caught with his pants down.” He had the same boyfriend for years and studiously kept his private life private, while all about him were flaunting theirs. More recently, with his safe sex posters and an interview in the Advocate, Meisel opened up a bit. He said he’s always photographed “more effeminate-looking men, more masculine-looking women, and drag queens” in hopes of “teaching that there’s a wide variety of people…. There’s absolutely a queer sensibility to my work … but there’s also a sense of humor … a sarcasm and a fuck you attitude as well as a serious beauty.”

Meisel’s photographic career began inauspiciously. One night Spina took him to a party for Bette Midler. Meisel borrowed an old Exakta camera and took a picture of the singer that ran in WWD. He then took a class in photography. His parents bought him a camera.

Meisel met Valerie “Joe” Cates, an aspiring model from Park Avenue, in a vintage clothing store in 1979. He followed her, asked to photograph her, then asked the same of her sister, Phoebe, a top teenage model at Seventeen. “He was the first man we’d met with really long hair who was into dressing us up,” Phoebe recalls. “He was different and really playful. Our first grown-up friend.” Through the Cates sisters Meisel got work shooting test photographs of young models and an assignment from Seventeen. He also worked for the SoHo Weekly News. Fashion editor Annie Flanders gave him his first cover assignment and a story on plastic clothes. Joe and Phoebe Cates modeled.

Flanders knew that her friend Frances Grill, a photographer’s agent, was looking for new blood. Meisel went to see her. She was impressed. “He knew every single bit of information about every photographer, every model.” She sent a carousel of his slides to Kezia Keeble, an ambitious stylist who’d once worked for Diana Vreeland and was looking for a way into fashion’s pantheon. Keeble had just been hired to create covers for Condé Nast’s Self magazine. Meisel had never worked in a studio, and he didn’t want to leave his WWD job. “He was really insecure,” Grill says.

He had reason. An assistant—who was “promised tons of work by Kezia Keeble to show Steven how to do it”—would set the lights and the camera, says someone who watched them work. “Kezia didn’t know the front of the camera from the back. She wanted a photographer she could mold. He was her boy. He would tape Avedon spreads to the floor of the studio and say, ‘Light it this way,’ and, ‘Pose that way’ All he would do was push the button.” Christopher Baker, another assistant, says that all Meisel owned was one Nikon and one 105 mm lens. “He didn’t care. It was weird,” Baker says. “He was, like, chosen.”

Meisel shot half a dozen Self covers, helping turn the new magazine into a million-selling success. He was also working regularly for Mademoiselle and its Italian equivalent, Lei, and, every once in a while, for Vogue. He fitted into his new milieu well. Models loved him; he’d have his makeup done before theirs. “He would speak to the models in sign language, put his hand a certain way, throw his neck, and expect her to imitate him,” says Andrea Robinson, who worked at Vogue. He wore kohl makeup and a little dirndl skirt over his pants.

John Duka—then Kezia Keeble’s summer housemate and soon to be her husband and partner in a PR firm—dubbed Meisel a new Avedon in his influential fashion column, “Notes on Fashion,” in The New York Times. Meisel quit his WWD job. The next step was to make a splash, and he did with a little help from his friends. In January 1983 Sprouse asked him to photograph some clothes he’d been making for a fashion show Keeble was doing. Though they were still sewing on the edge of the runway, the show was a success. “I knew I was looking at a gold mine,” Keeble declared. Bendel, Bloomingdale’s, and Bergdorf Goodman bought. Odd was in.

The first time Kezia Keeble ever saw Teri Toye, dressed in a demure Black Watch plaid jumper, turtleneck and stockings, ponytail, and flats (“indeed, an odd way for a transsexual to dress”), she knew she’d encountered someone extraordinary. Toye had become a model that fall, when Sprouse held his first fashion show. Frances Grill, who’d stopped repping and opened an idiosyncratic model agency called Click, soon signed Toye up. When the Fashion Group—an organization of women in fashion—asked Keeble and Duka to produce its spring 1984 showing of American fashion, Keeble recalled the group’s show of ten years before, starring socialite Baby Jane Holzer—Tom Wolfe’s Girl of the Year—and decided it was Teri Toye’s time. “Outrage makes Teri the person,” Keeble said, because “people love to buy what they hate. They resist, but resistance causes persistence. What’s most amusing is she’s becoming Girl of the Year just because I said so.”

A press blitz followed. But when it got to be too much, Toye failed her Svengali and escaped to Key West with Way Bandy, the made-up make-up man who could have been the Odd Squad’s godfather. One friend referred to what followed as “their little Peyton Place.” Another called it “a lover’s spat.” Meisel’s odd little squad fell apart. His agent called Toye “boring and sad.” Toye put it all down to a “high school girls’ fight.” Frances Grill, who lost touch with Meisel at the time, put it down to boredom. “Steven is fashion,” she says. “As fast as you think you’ve got it, it changes. That’s how Steven is. He moves on.”

Following the breakup of the Odd Squad, Meisel was seen far less in public, but his career took off. He quickly left Mademoiselle behind. Briefly he championed a Dutch-Japanese model named Ariane, who was dating a musician who lived in his building. He shot her in an influential makeup spread for Italian Vogue. “I didn’t look like a girl,” she says. “I didn’t look like a boy I looked like this rock and roll thing.”

Then came Christy Turlington. “I always wanted to work with Steven,” she says. But Vogue’s editors told her he liked only big, strong girls. “I kept asking,” she says, “becoming a little baby,” and finally a go-see was arranged. “So I met him one day, and he was very nice but didn’t seem to pay much attention.” It wasn’t until six months later, in 1986, that she finally worked with him for British Vogue. “I came an hour late, by subway, got off at the wrong stop—a disaster story,” she says. “But I worked with him for four days, and we had so much fun.” It was the first sitting where the team of Meisel, hairdresser Oribe Canales, and makeup man François Nars came together. Henceforth they worked together all the time. And over the course of the next several years they created a three-headed monster known as the Trinity: Turlington, Naomi Campbell, and Linda Evangelista, the three models who came to epitomize fashion.

The second figure in the Trinity was hardly haute when she arrived in New York that April to do her very first shoot—for British Elle. Naomi Campbell was discovered in 1985 by former model Beth Boldt, who’d opened an agency called Synchro in London. She spotted the fourteen-year-old Campbell buying tap shoes near her office in London’s Covent Garden. “She was wearing a little school uniform,” Boldt recalls. “I took her first tests, and she was sooo sweet, like sugar. Everyone who met her wanted to hug her.” Some might say they hugged the sweetness right out of her.

A theater and dance student from Streatham, England, and daughter of a dancer who’d traveled the world in sequins and plumes, Campbell was already show biz bound when she signed up for a modeling course at Boldt’s instigation. A few short months later she was on her way to America for Elle, where a pretty new black face was always welcome. “A girl from New York let them down, and Naomi got the booking,” says Boldt.

That summer Ford “traded” Turlington to London for a week in exchange for a Synchro model. “I met Naomi the day I got there,” Christy says. “We had lunch, and she was in high school uniform, hanging out at the agency. She was really cute. She’s still sweet, but she’s a completely different human being now.”

They hung out together and saw each other again a few months later, when they both landed at the Paris nightclub Les Bains at 4 A.M. Campbell had been taken up by Azzedine Alaïa, a diminutive Tunisian-born designer in Paris. Models loved his sexy clothes as much as he loved models. “He was way ahead of all of them,” says John Casablancas. “He created the fashion show as a social event, and he got every single superstar in the business to come for free.” He also let them stay in his house and referred to them as his daughters. “Naomi says I am like her mother,” he explains. “I keep an eye on her. Cities are dangerous for young girls. There is too much temptation. Everything is easy, and at that age they never think anything can happen to them. For models it goes very fast.”

It did for Campbell. Christy recalls, “I kind of felt protective over her, and I was only a year older. I also wanted the company. So she moved in with me.” Christy soon introduced Campbell to Meisel. “Because Naomi lived with me, we all hung out a lot,” Christy says. “So Naomi got in really quickly.”

The final member of the Trinity, the most dedicated model of the three, is Linda Evangelista. Though she’s been dubbed Evilangelista by wags at Elite, she’s also the most accomplished model of her time. “I know what and where I would be if I wasn’t modeling,” she once said. “I thank God every day for my looks.”

Born in 1965 to an Italian Roman Catholic family in St. Catharines, Ontario, she was the daughter, niece, and sister of General Motors auto plant workers. Her mother enrolled her in dance and self-improvement classes starting at age seven. She became a model as a teenager, working in local stores for $8 an hour. “Even when she was thirteen, I knew she’d be good at it,” her mother said.

Like Steven Meisel, Linda “was always obsessed with fashion—with the magazines, the models and the poses,” she’s said. She signed with an agency in Toronto and in 1981, at sixteen, entered a Miss Teen Niagara contest in Niagara Falls. An Elite scout was in the audience. Not long afterward she arrived in New York to test. But not much happened.

Determined to succeed, or at least not to return to Ontario, Evangelista packed her bags for Paris in 1984. Her father gave her a year to make it. “I thought I was good,” she’s said, but she was “doing mediocre jobs for $650.” She was her own harshest critic. “I didn’t really have myself so together,” she’s recalled. “I still had baby fat and the hair was a problem.”

“Actually, she worked very well,” says Francesca Magugliani, who watched her progress at Elite Paris. “She was doing covers right away for Figaro Madame and Dépêche Mode.” Then, Francesca recalls, Evangelista had a booking in Spain with Gérald Marie’s photographer friend André Rau. “She did a lot of jobs with Rau,” Francesca says. Upon her return Elite got a letter saying she was switching agencies. “André took her to Paris Planning,” Francesca says. “I called John, and he said, ‘Don’t give her her book.’ So she leaves, never calls for her book, never calls for her money. And that’s when she started her superstar career.”

Evangelista had been having an affair with Rau. “She was the only girl he ever loved,” a friend of Rau’s says. “He was two years with her. Gérald Marie stole this girl from him. After her he never recovered.”

Marie met Evangelista at his apartment in Paris. “She came with a friend, and we looked at each other, and in the same moment, boom!” he recalls. “She was with Elite. She was not an important model. I was still at Paris Planning, and she came to work there.” Christine Bolster was at Paris Planning, too. And she wasn’t Marie’s only girlfriend. “Gérald was going out with Linda, with one of my models, with a top booker, and with Christine,” said a competing agency owner. “There were at least four, and he said to each of them, ‘I love you, I’m going to marry you.’”

The next month, when Marie opened Elite Plus, Evangelista switched back, and Marie began making her a star. “Gérald made her career,” says Francesca. “Linda was madly in love with him.” He introduced her to his close friend photographer Peter Lindbergh. “I brought Peter to my place for dinner, and I told him, ‘I bet you when you start working with her, you’re not gonna stop,’” Marie remembers. “One month after, he booked Linda, and for one year and a half he never stopped booking Linda. He was the king of Italian Vogue, of Marie Claire; he was putting her everywhere.”

Their new alliance proved a boon to both Linda and Gérald. “Elite was never that hot,” says a Paris competitor. “With Linda it got really, really hot. Gérald was using Linda to meet all the photographers, imposing himself in the studios, all the luncheons. I think she’s really a cold fish. But she’s really clever at keeping relationships with photographers.” After a few months Marie and Evangelista came to New York. “We did a list of who we should see, and the first day she went to see Steven [Meisel],” Marie says. Evangelista was the perfect appurtenance for the peculiar photographer. Her desire to make great pictures transcended all else, and as time went by, she proved willing to be bent and shaped to Meisel’s every whim. “She had a tremendous desire for success,” says Marie. “And she is somebody who knew really quickly to correct what imperfections she had by moving differently, finding the angle for the light. She is no more or less beautiful than many other women, but she wants it really bad.”

By the end of 1986 Gérald Marie had “started speaking about marriage,” Linda said. “I never ever thought he would get married. So I said, ‘Well, put the ring on my finger and then we’ll talk about it.’ And he did. When I was on my way back here for Christmas, we had a dinner. He put the ring on my finger and I went into shock.”

In spring 1987 Christy Turlington returned from a location trip in Russia and went straight into a session with Evangelista and Meisel. “I was helping him,” Christy says. “He’d be looking for girls all the time. I got him to work with Naomi. Now Linda arrived. She was a little bit wary of me, because she knew we were all a team and good friends. I never had anything in common with her in the beginning. We were around her a few times, and she was nice; but I found she was a little competitive.” As it happened, the only pictures that ran from their first shoot together were of Evangelista. Her success with Meisel proved a perfect wedding present. Marie and Evangelista were married in July 1987 at St. Alfred’s Catholic Church, in Evangelista’s hometown.

Things began to happen fast for the Trinity after that. Their success was due, in no small part, to a shakeup at Condé Nast. Vogue was in a crisis, a result of the success of the upstart Elle, just launched in America. In June 1988 S.I. Newhouse, Jr., and creative director Alex Liberman decided they had to do something. In a stunning coup they fired Vogue’s editor, Grace Mirabella, and replaced her with Anna Wintour.

Wintour’s career in fashion began in her hometown of London in 1970, when she went to work for Hearst’s British Harper’s Bazaar (now called Harper’s & Queen). Moving to New York in 1975, she joined American Bazaar under Anthony Mazzola but didn’t last long. “Tony felt the sittings I was doing weren’t right for the American market,” Wintour says. “And he was probably right.” She went on to Penthouse publisher Bob Guccione’s women’s magazine, Viva, and New York magazine. She spurned Condé Nast’s early approaches, although she met with Mirabella. “Grace asked what job she wanted,” says an editor who heard of their encounter.

“Grace, of course I want your job,” Wintour replied.

Finally, in 1983, Liberman lured Wintour to Vogue with the new—and purposefully vague—title of Creative Director and a mandate to use her elbows. Liberman says he felt “an absolute certitude I needed this presence. In my innocence I thought she could collaborate with Grace and enrich the magazine. I’m not sure the relationship was the way it should have been.”

Both Wintour and Mirabella felt frustrated. “Things worked differently then,” Wintour says diplomatically. “Grace picked the clothes. There was one point of view. It’s not how we do it now.” Wintour got out in January 1986, when Beatrix Miller, the longtime editor of British Vogue, decided to retire. Her new appointment was controversial. Under Miller, British Vogue was a whimsical, eccentric magazine, much admired by the fashion crowd, but not terribly realistic. “It was a rare animal,” says Liz Tilberis, who started at the magazine after placing second in a 1969 Vogue talent contest. Wintour changed it, trading idiosyncrasy for rational uniformity, quirkiness for speed, the strangely erotic for the straightforwardly sexy. Suddenly the magazine looked just like Wintour, in her short skirts, high heels, bobbed hair, and dark glasses.

During Wintour’s first months on the job, unhappiness spilled into the pages of the feisty British press. For a supposedly civil people the British gave Wintour an extraordinarily hard time. They nicknamed her Nuclear Wintour, the Wintour of Our Discontent, and Desperate Dan, for, as the Evening Standard put it, “her habit of crashing through editorships as though they were brick walls, leaving behind a ragged hole and a whiff of Chanel.” By April 1987 speculation was fierce that Wintour’s chill reception in London was about to send her scurrying back to America. Pregnant again and often alone in a long-distance marriage, she began discussions with American Elle.

“I was having a hard time,” she admits. “It wasn’t a secret.”

Si Newhouse flew to London to see her—and keep her—by offering the editorship of another Condé Nast magazine, House & Garden. But Wintour’s eight-month attempt to remake the magazine (renamed HG) into a cross-disciplinary journal of style quickly ran into trouble. Things got so bad it was widely believed that Condé Nast operators were fielding an avalanche of subscription cancellations. “It was a horrible time,” Wintour says. “I thought I was doing an interesting magazine.” Meanwhile events outside Condé Nast were conspiring to take it away from her.

As Wintour crossed the Atlantic, Vogue still ruled the roost, but things were changing. It was the year of Elle. The slick, gorgeously printed Paris-born magazine was growing fast, and suddenly people were noticing it. In 1987 Vogue’s advertising revenues hit $79.5 million. Bazaar—still in a holding pattern under editor Anthony Mazzola—earned $32.5 million. Elle, at $39 million, was gaining fast and outselling Bazaar. Hearst seemed not to notice, but Condé Nast did. “There was a slight tremor,” Liberman says. “People looked at Elle carefully. There was something unconventional and a little new about its approach. It’s quite possible we learned certain lessons.”

Lesson number one? “It seemed a change at the top was necessary,” Newhouse says. “We had a magazine that needed attention.”

As far back as 1986 Liberman had let Grace Mirabella know that something was amiss. But he did it with “words I didn’t quite understand,” she says. “I’m the first to see nothing coming. Even a bus.” Si Newhouse admits that Mirabella’s firing two years later was badly handled. “Alex and I made the decision to change,” he says, and somehow it leaked to Liz Smith, who promptly broadcast the news. “The way it was handled was graceless—without making a pun,” Newhouse continues. “So, fine. But it wasn’t a spur-of-the-moment decision.” Within two days Rupert Murdoch got in touch with Mirabella. A few months later he made her an offer she couldn’t refuse: a new magazine bearing her name.

Wintour’s first revamped issue of Vogue appeared that fall. Linda Evangelista got a makeover at precisely the same moment. In October 1988 Peter Lindbergh convinced her to let Parisian hairstylist Julian D’Is cut off her hair—just as Gérald Marie’s previous charges Shaun Casey and Christine Bolster had done before her. “I was terrified,” Evangelista said. “I cried through the whole thing.” She was canceled from more than a dozen runway shows as a result, but she had the last laugh. “Between December and March I appeared on every Vogue cover—British, French, Italian, and American,” she later boasted.

Christy Turlington chose that moment to make herself scarce. In fall 1987 she met Roger Wilson—Shaun Casey’s ex-husband—at a party in Los Angeles. Before his marriage to Casey broke up, Wilson had decided to become an actor and debuted in Porky’s, a witless 1982 teen sex comedy that made a fortune. It kick-started his new career but also spelled the end of his marriage to Casey. “He says things didn’t work out because he had other things to do and she was used to having this young kid with a lot of money who was home all the time,” Turlington says. Wilson got a job on a television series. He dated model Kelly LeBrock. “Most of this stuff I found out afterwards,” Turlington says. “I thought he was a cute, sweet, normal guy when I met him.”

Around the same time Turlington did her first big-money job—for Calvin Klein. Bruce Weber was in the midst of shooting Klein’s faux-orgiastic Obsession perfume ads when Turlington flew in for two days. “The shoot was wild,” she recalls. “Tons of people. Guys and girls. The clothes would come off. I was like, ‘What’s going on?’” As the ladylike ads that resulted attest, Turlington kept her clothes on. She didn’t like the pictures. But Klein liked her. And during the fittings for his fashion show in spring 1988, he started questioning her closely about her ambition. Later that day Klein called her. “I have this really crazy idea,” he said. “I love you so much I would marry you, but I already got married. So I want you to be the girl for my new fragrance. Just do me a favor, don’t break me.”

Turlington starts hyperventilating remembering the moment. Eileen Ford tried to talk her out of it. But Turlington wanted to spend more time with her new beau, and being a contract model would allow her that. “I signed very quickly,” she says. “I didn’t have a lawyer. When I got home, Roger read the contract.”

“You’re screwed,” he said.

Though she was to be paid $3 million for eighty days’ work a year over four years, she was locked up. She couldn’t do interviews, editorial spreads, or any other advertising. At first that didn’t matter. The first month of her contract was a busy one. She shot photos with Irving Penn, began work with Richard Avedon on Eternity’s television commercials, and then headed to Martha’s Vineyard to shoot magazine ads with Weber. That’s when the problems started. Weber hadn’t been consulted on Klein’s choice of Turlington. “I think he should have had a voice in who the contract girl was,” she says.

Their first shoot together—inspired by Toni Frissell’s photos of Elizabeth Taylor, Mike Todd, and their daughter—went well. At least Weber thought so. Surrounded by children, Turlington “let her ego go completely,” he says. “Most girls are afraid of not being the star.” By giving up center stage to the children, he concludes, “she was the star of the shooting.” Unfortunately few of the photos ever appeared. “Calvin never ran that many pictures,” Weber says. “You know how it is: You shoot eight dresses, but they really only plan to run two. Christy was used to seeing a lot of pictures of herself. She really felt frustrated, and through that frustration she lost interest.”

Between shoots Turlington moved in with Wilson in West Hollywood, enrolled in literature and writing classes at UCLA, and went stir-crazy. By fall she was ready for a change in her relationship with Calvin Klein. Reports at the time said she’d angered Klein by getting her hair cut without his permission, but the real situation was considerably more complex. “I felt Bruce didn’t like me,” she says. “It would get real uncomfortable on the set. We’d be butting heads without speaking to each other. It was awkward. So I felt, fine, I’ll do my couple days work a year. But I did miss working—a lot.”

Watching from the sidelines while other models worked didn’t help her mood. She’d kept in touch through Naomi Campbell and Linda Evangelista, whose rapid rise coincided with Christy’s departure from the scene. Evangelista had even taken Turlington’s place on jobs she’d been barred from doing. “The year that I disappeared is when a lot happened for Linda,” Christy says. “She did Barneys after I left. I was supposed to go on a trip for Bloomingdale’s to China with Cindy [Crawford], and Linda got my spot.” Despite their initial wariness, they’d become friends. And by mid-1989 Christy was staying in Linda’s New York apartment in the same building where Naomi lived. Visiting them on sets, Christy grew green with envy. “Then I got a haircut.”

Christy had just finished a long Calvin Klein job and was taking a few days off in Woodstock with Oribe. As she drove in an open jeep, her hair got tangled in the wind. “I figured they wouldn’t need me for a month or two, so I said, ‘Just cut it,’” she recalls. They made a video of the shearing, laughing and joking about how they were going to get sued. Then Klein’s minions called with a photo assignment. “Uh-oh,” Christy said.

She’d already hired a lawyer to try to loosen the ties that bound her to Calvin Klein. Everyone knew it wasn’t working out. But suddenly the designer agreed, and her contract was renegotiated. Her agency was delighted. “You don’t want to stop the momentum of building a star,” says Katie Ford. But it took some time for her to get back up to speed. She visited Evangelista and Meisel on an Italian Vogue shoot, “one of their most beautiful series with lingerie and corsets,” she says. “They stuck me in a picture, and I was so uncomfortable. I was so unused to being photographed. My steam was very low, photographically.”

In Christy’s absence, Evangelista had become Meisel’s muse. “They worked together all the time, and he did beautiful pictures of her,” Turlington says. “I think Linda had been really monumental in his career, changing him as a photographer and being an inspiration. They did a really incredible variety of things that year when they started working together a lot.”

But now Turlington was back. And just as she’d helped Evangelista, says Gérald Marie, his wife returned the favor. “The relationship they had together was like two fingers, the same hand,” he says. “Linda took Christy by the hand to all the designers. Linda engaged her with Peter Lindbergh at the time, put her back together with Steven Meisel. To all these [people], Linda was very hot.”

So was Naomi Campbell. After arriving in New York under Turlington’s tutelage, she and Evangelista had become friends, often meeting at Meisel’s studio. Naomi also became a darling on the city’s scene—stage-managed by Meisel. “Yes, there was a strategy that had to do with getting noticed,” he said. “It was simply a question of publicity.” It started coming after December 1987, when she met heavyweight champion Mike Tyson at a party at designer Fernando Sanchez’s apartment. Various versions of their meeting have the sexually hypercharged Tyson virtually molesting her before guests pulled him away. Told she was only a baby, he replied, “I’m a baby, too.” Around then, Campbell approached a reporter at Azzedine Alaïa’s house in Paris, rubbed against him, and asked, “When you gonna write a story about me?”

By the time Turlington was freed from her bondage at Calvin Klein, Campbell had emerged as a star, with covers of both French and British Vogue behind her. So suddenly, instead of one muse, Meisel had three in residence at the all-white Park Avenue studio he dubbed the Clinic. “We re-make people,” he once said of the place. “We make them beautiful.” In 1988 he began photographing Turlington, Campbell, and Evangelista together because “he thought it would be a neat look,” says a stylist. “Steven made them the Trinity by booking them together. He does such great work, and he’s so charismatic he kind of possessed them. Being in Steven’s studio is like being with the cool kids in the lunchroom in high school. Christy got into it for a while, but it never suited her. She was like Cinderella with her two stepsisters. It was a phase. A naughty phase.”

Just as he had with Teri Toye and Stephen Sprouse, Meisel turned the models, his stylists, and friendly editors like Vogue’s Carlene Cerf into the in-est in crowd in fashion. His power shed light on how fragile a grasp most fashion editors had on their trade. “That guy could say a piece of crap was fashionable, and we’d all go Yes!” says an editor at Vogue.

Meisel’s control was absolute. “I don’t think he liked any of our boyfriends,” Christy says. “Linda he couldn’t help because she got married before we met her. But as far as what I did and Naomi did, he was very protective.” All-consuming is more like it. “They became a cult,” says Polly Mellen. “They moved together, went out together.” They even began to be booked together.

In 1988, when Ford Models abruptly ended its relationship with Karins, Turlington signed up with Elite in Paris, at Evangelista’s instigation. Naomi Campbell had been with Elite Paris ever since Beth Boldt discovered her. Now Gérald Marie began aggressively packaging Christy and Naomi with his wife. “It started just because they were girlfriends,” Marie says. “But it was really nice to promote them together, sell them together, put in the client’s brains some ideas about them being together. If you want those two, why not take number three? They gained three hundred percent out of this pact.”

“That first season after I went back to work, he booked us for all the shows,” Turlington says. “We’d never done shows before in Paris, so he somehow built some hype around Linda and I. There’s not that many girls who look good together. We complement each other. Naomi’s a very good friend of mine and Linda’s, so somehow that all happened.”

Watching Gérald Marie from the sidelines, John Casablancas felt a new respect for his former enemy. “Gérald positions a girl, makes her understand what her star quality is all about, maintains the prices, the pressure; he does not get intimidated; he’ll lose a big booking; he’ll select photographers really intelligently; he does a tremendous job,” Casablancas says. “There was also the social scene. He not only had the talent and the understanding, but he was married to Linda, so he was a player. I’m an agent, but I don’t go behind the scenes the way he did. So I think this gave him an extraordinary position.”

Graciously Marie says it was his photographer friends who sent the supermodels into orbit. “The photographers who pushed the most and created the models are Steven Meisel and Peter Lindbergh,” he says. “But the models got so enormous in answer to the sudden need of the time. Actresses started to hide themselves, and people needed something else in their mouths. So, next story came the models. We were right there at that moment.”

Naomi Campbell’s affair with Mike Tyson survived his marriage and divorce from actress Robin Givens. When she appeared at ringside at one of his fights in February 1989, their semisecret relationship went public and increased her renown immeasurably. That September she became the first black woman ever to grace the cover of the all-important September Vogue. Three months later she and Tyson finally admitted their affair in the same magazine. “She has a great body and she’s scared of nothing,” the boxer said. “That’s why I like her.”

In January 1990 the cover of British Vogue featured Turlington, Campbell, Evangelista, Cindy Crawford, and Tatjana Patitz. So impressed was pop singer George Michael that he cast them all in his next music video, “Freedom.” It was filmed in August 1990. Evangelista had just bleached her hair almost white. “I spend all my free time coloring my hair,” she said later. Her constantly changing coif became big news.

Publicity seemed to come naturally to the Trinity. Campbell got more when, hard on the heels of her breakup with Mike Tyson, she began seeing Robert De Niro and Sylvester Stallone. Christy and Linda got into the swing of things in April 1990, when they went to the Roxy, a New York disco, and were photographed straddling each other in a giant swing suspended over the dance floor. Needless to say, rumors they were lovers followed.

All the action didn’t do much for Evangelista’s marriage to Marie. They saw each other only five to ten days a month, “and that is a good month,” Marie said. But there were compensations. “I like the traveling,” Linda said, “the money … seeing myself in magazines. And I love clothes.” Marie was having a good time, too. He convinced designers, beginning with Gianni Versace in Milan, that it was worth paying double, triple, even ten times more than ever before, to put gaggles of top editorial models on their runways. They were paid back in international publicity. Versace, whose design antennae are particularly attuned to the new, “liked what he saw,” says Polly Mellen. “They affected his designing. Then they moved from Versace to Chanel.”

Finally, they were everywhere—or at least seemed to be. Versace’s exclusive bookings—paying extra to be the only designer a girl worked for in Milan—started it. “Then all the other designers said, ‘I’ll match that. I’ll pay you the same thing, and you don’t have to be exclusive,’” Turlington recalls. “The designers said, ‘You can do ten shows if we all approve of the other designers, and you can all be paid the same amount of money.’ It got bigger and bigger because they were outbidding themselves. Every year I thought, I can’t make more than this, but every year I almost doubled my income. It’s supply and demand, like sports. The best of the sports people will be paid any amount.”

Runway by runway, atelier by atelier, magazine by magazine, the Trinity conquered. Whole issues of the various Vogues seemed to be dedicated to their worship. “I never thought that models could take so much space in the world and in people’s impressions,” Marie avers. “But we followed the movement when we started to smell and feel that people were asking more about the girls. We saw that if you put a photographic model on the runway, they started to get really famous right away, because they get photographed by three hundred people at the same time, and some designers understood right away. Then we started to ask the magazines to name the girls. Then we worked to make the models a little more famous, to introduce them a better way, to produce their careers, to insist on certain things to do, certain things to avoid. I was not the only one. People catch on fast. If I ask the magazines to put the name of the girl on the cover, the agent next door, he’s not stupid, he’s going to ask for the same thing. That helped.”

From her privileged perch at Vogue, Polly Mellen saw the Trinity blossom—and then watched fame go to their heads. “They were always together,” she says. “It was a clique and a tight one, believe me. Occasionally they would talk to other people, but basically they talked to themselves. They’d consult on bookings. One would say to the other, ‘You’re past working with him.’ They were able to pick and choose what they wanted to do. The more they asked for, the more they got.” First a short list of supermodel-ready lensmen: Demarchelier, Meisel, Elgort, Lindbergh. Then the Concorde, then cars and drivers, personal chefs, and the best suites at the best hotels.

“They could write their own tickets,” says Mellen. “And they knew it.”

Back at the Anne Klein shoot, late in 1991, Turlington is eating rice and broccoli from an aluminum tin while simultaneously getting a pedicure and leafing through a pile of old magazine clippings. Right on top are two stories about her famous friendship with Evangelista and Campbell. Those pieces caused Christy endless grief, thanks to tactless comments, mostly made by Evangelista, about the unprecedented sums the three models earned and their feelings about the world of fashion. “We don’t vogue—we are vogue,” Linda told People. To Vogue, she revealed, “We have this expression, Christy and I: We don’t wake up for less than $10,000 a day.”

“I’d never say that,” Christy gripes, dropping her fork into the Chinese food. And though she truly believes Evangelista didn’t mean to appear crass, after those stories came out, Christy had a nightmare about them. “I was on the Arsenio show,” she says, “covering Linda and Naomi’s mouths with my hand!”

That $10,000 quote, more than anything, began the backlash against the Trinity. Soon everyone was taking shots at them. Even ArtForum described supermodels as “totally packaged commodities,” “live cash,” and “professional surrogates for the frustrated emulative instincts of the mass pecuniarily deprived.” It was later said that Evangelista’s words had been taken out of context. But insensitivity was a leitmotif of the Trinity. Not long afterward Linda was approached by France’s Nouvel Observateur for an interview on modeling and asked $10,000 plus a 20 percent service fee. The paper replied by telling readers how many Somalis could be fed for that sum.

On another occasion Evangelista defended the price of her services. “Before supermodels, there was one price for everyone. I don’t think a new girl should get the same,” she said. “That’s why Gérald introduced the new price. If you wanted me, there was no way ’round.” In another interview she announced that “I have become bigger than the product.” Campbell’s antics at fashion shows, including refusals to share the runway with other black models, didn’t win her many friends either. The shows had always run behind schedule, but when “the late” Naomi Campbell was added to the mix, editors and buyers could count on an extra half hour’s delay. “I won’t use her,” said designer Todd Oldham. “We have a No-Assholes clause.”

The Trinity’s disdain worked as a pose on the runway, but when the girls were quoted in cold type, they came off like spoiled little snots. “The girls you speak of,” says one of America’s most renowned fashion editors, “are rude because everybody coddles them. We do what we need to get what we want, but it’s beyond. I was at a party where a waiter grazed Linda’s arm, and she screamed, ‘You burned me!’”

“They became very powerful and not nice about it,” another top model says. “They were very snobby and cold and shut people out. We had to deal with the disgusting influx of negative attention to models that they generated.”

“I have to beg, borrow, lie, and steal to get them,” says a top model editor. “You have to have the right photographer, the right makeup, and a ninety-nine percent cover guarantee. And we booked them all when they were starting, when they were no good.” Besides disenchanting their old friends, the Trinity was also courting overexposure. Fickle fashion people were already tiring of this latter-day Terrible Trio when a People article appeared, chronicling a bitchy night on the town with Meisel and the models. “Naomi and Linda really wanted to do it,” Christy says. “I didn’t at all. But they made me do it. It was really tacky and horrible, and I was so embarrassed. It pissed my mom off. And they didn’t even quote the worst things that were said that night.”

Turlington knows that a model’s public image is a fragile thing. “People don’t want to like you,” she says. “You’re young and beautiful and successful. They think you don’t have a skill. So when things go well for you, they aren’t happy. That’s just human nature.” She knew not to rub people’s faces in her success. But her friends didn’t. And now, Christy was seeing the downside of her in-crowd.

“I’ve never thrown any kind of fit; I’ve never refused to wear anything; I’ve never refused to do a picture,” she says. “But girls do that all the time. Naomi can be a little difficult. I love her dearly, but people know she can be difficult. ‘Difficult’ meaning, ‘she needs to be entertained.’ Then she’ll do her job very well. Linda is difficult, on the other hand, because she knows herself very well. She knows all of her imperfections. She does not want to look stupid. That’s her job, really. She’s doing the best that she can for them. And it’s to their advantage that she does that. Linda knows what’s best.”

Despite their continuing mutual-admiration society, the Trinity disbanded in 1991. The more time they spent together, the more their differences became apparent. Evangelista, the most malleable of the three models, became Meisel’s clear favorite. “Christy does the job,” an insider says, “but she can turn it off, go home, and live a life. That became a problem.”

Christy agrees: “I love fashion, but I’m not obsessed with it.” Linda’s obsession and plasticity clearly appealed more to fashion’s most plastic photographer. “Women today are striving to be perfect, to be the ultimate Barbie doll,” Meisel has said. “I can’t think back in history where women have been so plastic. I mean, how many women are going out to have face lifts and are having their teeth done and are dying their hair? Sociologically, it’s definitely a modern thing.”

In September 1991 Linda dyed her hair red and won thirty pages and the cover of Vogue. “Meisel used Linda much more than Naomi and Christy, and it really hurt Naomi, but that’s what photographers do,” Polly Mellen observes. “His eye never tired of Linda. It was about manipulations and jealousies and a real craving to work with the best, and Linda was, and they wished they were.”

“I think it blew up because girlfriends have their ups and their downs and sometimes don’t get along,” says Gérald Marie. “There were certain jealousies and little things between makeup artists, girl stories. Everything was so big it started to be ridiculous.”

Christy got lonely in the in crowd. “I was successful before I knew any of them,” she says. “I’d always been an individual, and I started feeling like part of a package deal. When I was younger, I wanted to be talked about because of me, not because of what I wore or who I was hanging around with. And I was always that way, until we were together. At first I didn’t pay much attention to what things looked like. And then all of the sudden people starting thinking that Linda was a ringleader. I’ve been around longer than she has, and people are thinking that she’s controlling me! I hated the idea of people thinking that. I wanted to distance myself, not work with anybody else. Be myself again.”

They all knew it had gone too far. “Of course, people got bored with us,” Christy says. “We were bored with each other. We even thought about staging a fight on the runway.” (They didn’t.) But Naomi and Linda were fighting (“They always fight,” says Turlington. “And always have. It’s love-hate. Not even love, just me, me, me. They’re like sisters”). And Turlington was having arguments over money with Elite in Paris. “They were very slow in paying, and I wasn’t used to that,” she says. “Ford paid me immediately. So it was always uncomfortable because it’s my good friend’s husband that’s my agent, and I can’t call him up and scream like I can to my normal agent.”

In spring 1991, after Ford opened a Paris branch, Turlington and Campbell both signed up. When Elite’s lawyers sent her a threatening letter in response, Christy got mad. “Linda knows everything that goes on with that agency,” Christy says. “She tries to stay on the outside, but she is in the middle. It’s her husband. Nothing was ever mentioned. If there is some kind of problem, they don’t have to make it a legal situation, they can call me. I will do my best to make it right. I felt hurt because of that.”

A close friend of Christy’s thinks the breach was inevitable: “The infatuation boiled down to real people. They were a neat look, but that doesn’t make you best friends.” For months afterward they hardly saw one another. Later Marie said that his feelings had been hurt. “Christy was staying home with us, going to weekends,” Marie says. “We are really close friends, and when you help set her back into the market and [she] leaves you for whichever money deal she could have, you feel like someone shot you, bang [in] your head, and your wife’s, too.”

For two days during Turlington’s shoot for Anne Klein late in 1991, Linda Evangelista was working in a studio next door with Steven Meisel, shooting ads for Barneys New York. On the first overlapping afternoon Meisel’s set was still humming when Christy’s shut down. Christy stuck her head in. “Turlie!” Evangelista cried when she saw her friend. “I didn’t see you for so long!”

Catching up for several minutes, Evangelista told Turlington about her recent operation to repair a collapsed lung. She’d had to decide whether to recuperate with her husband or her mother, she confided, and she’d chosen her mother. It was a sign. By the next July, when French Glamour ran a spread on their villa in Ibiza, Gérald and Linda had already separated. “We are still married but we are no longer lovers,” Marie told an interviewer. “We decided one day to lead separate lives…. Linda is not a bird that you can keep in a cage…. We both needed more space and freedom…. She was only spending four or five days a month with me…. If you stay away from the person you love for three weeks … you get independent. You exist … as a single person…. Linda is one of the most beautiful women in the world but there are lots of others.” He was obviously quite pleased that she, like Christine Bolster, was staying with Elite. “I have loved Linda and kept her,” he concluded. “I haven’t lost her.”

But he had. “Something happened,” says the head of a competing agency in Paris. “Linda didn’t believe the rumors. Then she walked out on him. He was destroyed.” The story went around that he’d hooked up with a booker at a third agency. “Maybe he needed a mother at that point,” the agency head snickers.

The separation wasn’t made public for months, while gossip raged in fashion circles that Evangelista had taken up with actor Kyle MacLachlan, whom she met on Meisel’s set at another Barneys shoot. The talk was fed by Evangelista’s disappearance from fashion runways for several months. She finally reemerged in March 1993 at the Paris shows. That season she gave an interview in her suite at the Hôtel Ritz. “We separated in August and I started seeing Kyle after Thanksgiving,” she said. “I liked him. He was sweet, but I wasn’t looking then…. What went wrong? I haven’t got the words.”

Christy got a famous boyfriend, too, dropping Roger Wilson and picking up with actor Christian Slater, then dropping him for Jason Patric. Turlington also became best buddies and something of a modeling mother to Kate Moss, the leading member of the post-Trinity generation.

Naomi Campbell hasn’t been so lucky in love. After being linked to Eric Clapton, she hooked up with U2’s Adam Clayton for a long engagement that finally led them to alter their plans. Then, in November 1993, Monique Pillard and John Casablancas faxed a letter around the world about her. “To Whom It May Concern,” it read. “Please be informed that we do not wish to represent Naomi Campbell any longer. No amount of money or prestige could further justify the abuse that has been imposed on our staff and clients. All who have experienced this will understand.”

Those in the know said Campbell had at last made one demand too many—for a room at the sold-out Four Seasons Hotel in Milan during collection week. “Buy a first class hotel? Fuck you,” said Roberto Lanzotti, who works closely with Elite. “I don’t need that. I get rid of Naomi in the middle of the collections. I don’t want to represent her anymore. She was a pain in the ass. Forget it. It’s too much.”

The members of the Trinity all continued to have healthy careers, but their modeling moment was over.

On the last day of Christy’s shoot for Anne Klein, she headed next door to Meisel’s studio to say good-bye to Linda before flying to her next job. There she spied Lauren Hutton, the original contract girl, and the photographer quickly shot a roll of pictures of the three women. Christy pinched Linda. Lauren screamed and mugged. Then Turlington ran for the door, her floor-length pea coat cradled in her arms.

“Bye,” she called to Evangelista. “I’ll call you.”

“Really?” Evangelista answered. “Turlie? Aren’t you going to be cold?”

“Thanks, Mom,” Christy replied, throwing her coat around her shoulders.

“It feels like Paris used to feel,” Linda said wistfully as Christy turned to leave.

Outside, a silver town car was purring at the curb. Christy glanced up to the windows of Meisel’s studio. A strobe light flashed once, and again, behind the dirty glass. And then Christy Turlington clambered into her car and was gone.