6

How a Yogi Taught the Beatles to Relax

Don’t worry about the future. Or worry, but know that worrying is as effective as trying to solve an algebra equation by chewing bubble gum.

—Mary Schmich, American journalist and Pulitzer Prize winner

India’s Maharishi Mahesh Yogi Takes on Harvard’s Herbert Benson

In 1967, doctor and cardiologist Herbert Benson was doing blood-pressure experiments with monkeys at Harvard Medical School. That was also the year the Beatles started looking for meaning in their lives. In Paul McCartney’s words: “We’d been into drugs, the next step is . . . to try and find a meaning.” So when an Indian guru named Maharishi Mahesh Yogi visited London, the Beatles visited him. They liked what he said, so in 1968 the band members traveled to India with their wives and girlfriends to do a meditation retreat with him. Inevitably, an army of newspaper and television reporters followed. When the media arrived there, they found even more stars at the Maharishi’s ashram: Mike Love from the Beach Boys, Mia Farrow, and Donovan were already there. Although the Maharishi did his best to give the stars some peace by keeping the reporters away, their visit was publicized all over the world. Eastern spirituality suddenly became very trendy.

Emboldened by the Maharishi’s fame, some of his meditators visited Harvard researcher Herbert Benson. They told him that the kind of meditation the Maharishi taught, called transcendental meditation, could reduce blood pressure the same way that drugs could. Initially Benson thought this was too wacky and politely sent them away. But the meditators were persistent and kept coming back. Eventually Benson decided to get rid of them by doing a proper trial of transcendental meditation to prove once and for all that it didn’t work. Benson also had a condition: he would only study meditation if the Maharishi Yogi himself agreed to participate. That way, when Benson proved the technique didn’t work, he would expose the Maharishi as a charlatan. For his part, the Maharishi was convinced that meditation did work, so he agreed to Benson’s condition. He looked forward to a Harvard researcher giving the practice a firm scientific basis.

Benson set up the experiment by connecting meditators to mouthpieces, nose clips, and tight-fitting face masks. These conditions were not conducive to deep relaxation. In spite of this, Benson’s first study with thirty-six meditators aged seventeen to forty-one years old found that meditation lowered breathing rates, oxygen consumption, and blood acidity (which is associated with stress). The first study didn’t show a change in blood pressure, but that was because the meditators were young, healthy, and already had low blood pressure. He did a follow-up study with older patients who had high blood pressure and found that meditation lowered blood pressure by an amount similar to that obtained with drugs.

Benson described the state induced by meditation as a “wakeful hypermetabolic physiologic state.” It was similar to sleep, because the inner conditions for regeneration and recovery were being induced. But the meditators were not actually asleep, and the brain-wave frequencies observed during meditation were those associated with deep relaxation, rather than the frequencies observed during deep sleep. It was basically the opposite of the fight-or-flight response described in Chapter 5.

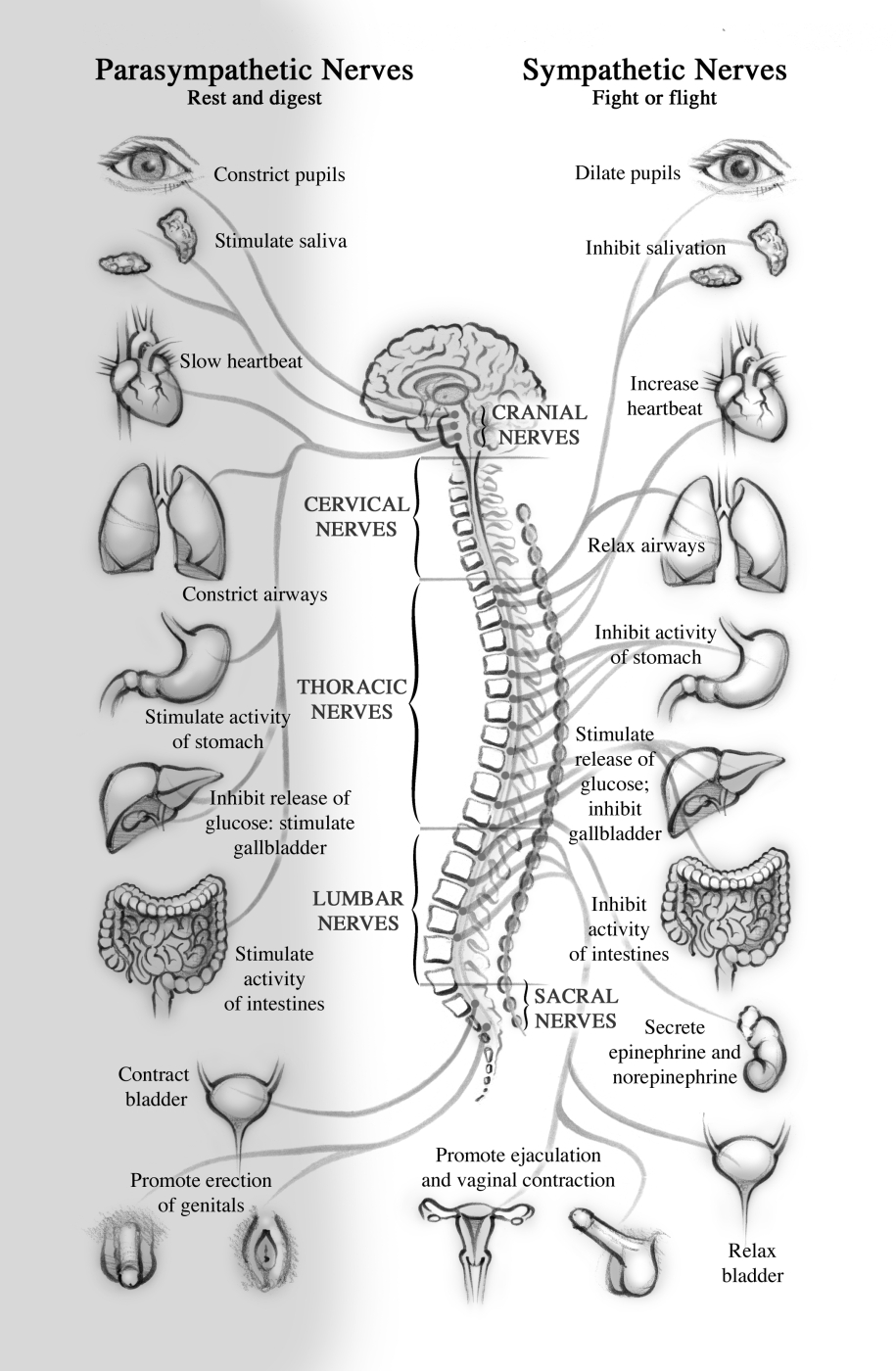

Whereas the fight-or-flight response is associated with the sympathetic nervous system, the relaxation response involves the parasympathetic nervous system. The word para in Greek means “against” or “contrary to.” That’s why a nickname for the effects produced by the sympathetic nervous system is the “fight-or-flight” response, and the effect produced by the parasympathetic system is called the “feed-and-breed” response. The parasympathetic nervous system is composed of the linked nerves connecting your brain and spinal cord to numerous organs of your body to help you to relax, digest, and breed. Parasympathetic nerves activate the body’s digestive system, the sexual organs, and other nerves responsible for slowing down the heart and breathing rate. When there is no need to fight or run, we can relax, enjoy our food, and think about other more pleasant things. That is when the parasympathetic nervous system is active.

There are three main ways in which relaxation and meditation activate the feed-and-breed (parasympathetic nervous system) response. First, relaxation and meditation take your mind away from the mental sources of stress, and we saw in Chapter 5 that a lot of the sources of stress come from our mind rather than from the outside world itself. When you are focusing on your body or your breath, your mind is not preoccupied with what your work colleague did to you yesterday, or how you plan to take revenge tomorrow. With the mind no longer focused on the source of the stress, your body and mind can relax.

Second, when you relax, your breathing rate slows down. Since the parasympathetic system works as a whole (as you know if you did Chapter 5’s exercise, and as I’ll explain more immediately below), the slower breathing rate activates everything associated with the parasympathetic nervous system. So you get a full “feed-and-breed” response just by slowing your breath.

Finally, in meditation (and, obviously, in the relaxation response) your body is more relaxed. Allowing your body to relax sends a message to your brain that things are okay, that there is no threat, and that you can move into the feed-and-breed response. So the parasympathetic system counteracts the sympathetic nervous system. Even though the sympathetic and parasympathetic nervous systems are opposites in many ways, they share two important qualities.

- • Both the sympathetic and parasympathetic nervous systems come more or less as whole packages, and the components of each system all get switched on or off together. In the sympathetic nervous system, when you see a wolf, it is not just your pupils that dilate: all the other things, like increased heart rate, suppressed digestion, and lung vessel dilation, happen together. Similarly, with the parasympathetic nervous system, the body muscles seem to relax in a connected way. For example, there is some evidence that if you relax your jaw, your whole body relaxes.

- • Both the sympathetic and the parasympathetic nervous systems are part of the body’s autonomic (a fancy word for “automatic”) nervous system, meaning they are usually not within our conscious control. When your brain perceives a wolf, the fight-or-flight response kicks in without you telling it to do so. When you lie down tired after a long day, your relaxation response kicks in, in a similarly automatic way. Contrast this with the part of the nervous system that is within our conscious control. When I move my fingers to type these words, or when I reach for my tea, my hands are consciously directed by my will. Philosophers debate the possibility of free will, but we will leave that for another day.

There is one thing to add about the automatic nature of the sympathetic and parasympathetic systems. They are not completely automatic because, as we saw in the takeaway from Chapter 5, and as we will see from the takeaways in this chapter, we have some control over them. The easiest way to influence them is by consciously regulating our breathing.

Benson wanted to publish what he found out about meditation for the scientific community around the world. But he had a problem. Just as he was sure that transcendental meditation was bunk until he saw it work with his own eyes, his Harvard colleagues were likely to think the same thing. They might think Benson had become a long-haired hippie who had started smoking too much marijuana with the Beatles. But Benson was smart, and he thought of a way to share his discoveries with the world without being viewed as a quack.

His trick was to use the term relaxation instead of the term transcendental meditation. He wrote a book titled The Relaxation Response, which quickly became a bestseller. Benson’s use of a new name not only helped him avoid getting ostracized by his colleagues, it was also more accurate. The Maharishi’s transcendental meditation was great, but it was not the only game in town. There are hundreds, if not thousands, of types of meditation out there. I have tried about thirty different kinds myself.

Besides meditation, hypnosis, some kinds of prayer, and traditional yoga all have physiological effects similar to those of the relaxation response. By traditional yoga, I mean forms that involve breathing techniques and mindfulness alongside the poses. (Most yoga practiced in the West focuses on the poses and their physical benefits.) The relaxation response is common to all these practices, so Benson did more than choose a new name. He found that many of these practices share a common effect: they all activate the parasympathetic nervous system and the relaxation response.

More recently, mindfulness has become all the rage. You can take courses in it, download apps to help you develop it, and learn how to use mindfulness to be a more effective leader at Harvard Business School. The mainstream use of the word mindfulness has its origins in a rebranding similar to the one Benson pulled off when he dropped the term transcendental meditation in favor of the term relaxation response. Here’s what happened.

The godfathers of mindfulness, such as Jon Kabat-Zinn, started off as Buddhist meditators and faced the same problems with their families that Benson experienced with his colleagues. Their non-Buddhist (Christian or Jewish) family members thought Buddhism was incompatible with their religions, despite its lack of a deity to worship. So Kabat-Zinn began using the word mindfulness in place of Buddhist meditation. He also took away all the foreign words and rituals like chanting. As a result, Christians, Jews, and Muslims can practice Buddhist meditation without offending their priests, rabbis, and mullahs, as long as they call it “mindfulness.”

Anyone who has experienced and understands the rudiments of Buddhist meditation and mindfulness will tell you that the two practices are very similar. Sometimes they look very different, because mindfulness teachers often teach in jeans and have ordinary hairstyles, whereas most Buddhist monks shave their heads and wear robes. And there is often some chanting before a Buddhist meditation session. All the chanting I have heard simply involves repetition of simple, nonreligious phrases like “please give me inner peace.” It does not refer to any god.

More important than the difference between Buddhist meditation and mindfulness is the difference between individual teachers. It is important to find a teacher who is qualified and who you feel comfortable with. Strange questions can arise when we sit still for a while, and having a good teacher to debrief with can help. The choice of an appropriate teacher is an individual one. A teacher who is great for me might not suit you and vice versa.

Because the word mindfulness avoids spooking people, and because it helps most people, mindfulness meditation has spread like wildfire. In the end, it doesn’t matter what word you use and it doesn’t matter whether you prefer relaxation, traditional yoga, or something else. If you are interested in it, the important thing is that you do it, because it can improve your health.

Evidence That the Relaxation Response Improves Health

A recent systematic review that contained four randomized trials involving a total of 430 participants showed that practicing the Maharishi’s transcendental meditation for fifteen to twenty minutes, twice per day, could lower blood pressure and help people live longer. One of these trials found that three years after it had ended, all of the participants who meditated were still alive, compared with only 77 percent of those who did not, meaning that meditation seemed to increase survival by 23 percent. The trials in the review were small, so more studies are needed to investigate the benefits of meditation. However, when considered alongside studies of similar techniques such as yoga and Tai Chi, we see similar benefits, making transcendental meditation results quite credible.

Mindfulness meditation can also reduce anxiety and depression. A large review including forty-seven randomized trials involving a total of 3,515 people found that mindfulness had effects similar to those of drugs for reducing stress, anxiety, pain, and depression by more than 10 percent, which is roughly the same as or better than many common drugs for these ailments, but without the side effects. The practice was also shown to improve quality of life. One trial in the review looked at people who had the challenging task of caring for a family member with dementia. It can be dangerous to leave people with dementia alone, so their caregivers must supervise them constantly. This causes caregivers to neglect their hobbies, exercise, and friends.

Such caregiving is often a stressful role, so it should not surprise us that people who care for family members with dementia develop numerous health problems of their own as a result. In the study, half of a group of seventy-eight caregivers were given a mindfulness training course, while the other half were given other types of education and support. After six months, the group that did mindfulness reported having 25 percent less stress than the group that just had simple education. There was no change in anxiety, but depression was reduced by 10 percent more in the mindfulness group. These effects are greater than the effects of drugs for stress and depression reduction.

The number of systematic reviews in this area is growing and they are almost universally positive, showing that these techniques are sometimes as good as many common drugs or can be used alongside the drugs to enhance outcomes. The other great thing is that none of the studies have shown any significant harmful side effects of meditation. Here is a sample of diseases that systematic reviews show relaxation can help cure:

- • Anxiety and stress. Two systematic reviews with a total of 74 trials and more than 5,000 patients showed that relaxation therapy/mindfulness reduces anxiety by more than 10 percent.

- • Arthritis. A systematic review of 11 randomized trials showed mindfulness therapy reduces chronic pain such as arthritis.

- • Asthma. One review with 15 trials suggests that relaxation techniques improve lung function in asthmatic patients. A more recent randomized trial showed mindfulness improves quality of life and reduces stress in those with asthma. Another found that relaxation techniques could reduce blood pressure in pregnant women with bronchial asthma.

- • Depression. A review including 12 randomized trials suggests a modest benefit from relaxation meditation in reducing depressive symptoms. Another review with 6 randomized trials suggests mindfulness can prevent relapse into depression.

- • Diabetes mellitus. A review with 4 trials found that yoga is likely to improve diabetic symptoms in patients with type 2 diabetes. Another review with 5 trials found that yoga has positive short-term benefits on fasting blood-glucose levels.

- • Hypertension (high blood pressure). A review of 107 studies shows meditation reduces high blood pressure.

- • Insomnia. A review with 112 studies suggests that most trials of mind-body techniques reduce insomnia symptoms.

- • Irritable bowel syndrome (IBS). A review of 8 trials found that relaxation meditation can reduce IBS symptoms.

- • Low back pain. A review including 10 randomized controlled trials involving a total of 967 patients found strong evidence for the short-term effectiveness and moderate evidence for the long-term effectiveness of yoga in reducing chronic low back pain.

- • Multiple sclerosis. A review with 4 high-quality randomized trials showed that mind-body interventions, including yoga, mindfulness, relaxation, and biofeedback (a technique in which patients monitor bodily parameters such as heart rate in order to learn to control them) reduced a variety of multiple sclerosis symptoms.

- • Psychological health (well-being) of cancer patients. A review of 3 randomized trials of an intervention that combines mindfulness with yoga reported positive results, including improvements in mood, sleep quality, and reductions in stress, which can help improve subjective well-being (including reducing depression and anxiety symptoms) and quality of life.

- • Stress due to HIV/AIDS. A review of 6 trials showed that the relaxation response or traditional meditation/mindfulness can help improve the following health problems that HIV patients often suffer: anxiety and stress, asthma, arthritis, depression, diabetes mellitus, hypertension (high blood pressure), insomnia, irritable bowel syndrome, low back pain, and multiple sclerosis symptoms. These techniques also can help improve general well-being.

Some studies also show the relaxation response can boost the immune system. There is even evidence that relaxing helps you solve problems.

Relaxation and Creativity

Besides health benefits, the relaxation response can also help us think of creative solutions to problems, including solutions to things that cause stress. Let me explain by means of the following candle problem. A candle, matches, and a small box of drawing pins are all lying on a table. The table is up against the wall, and there is a corkboard on the wall. Your task is to fix the candle onto the corkboard in such a way that the wax does not drip on the table below. If you have never tried this riddle, stop reading here and give it a try (or think about how you might solve the problem).

People often try attaching the candle to the corkboard with drawing pins, but that does not work because the pins are not long enough to go through the candle. Others try to melt the candle wax on the side of the candle then stick it to the wall. But that doesn’t work because the corkboard is too slippery and the candle falls. Eventually many people figure out that the solution is to empty the drawing pins from the box, pin the box to the corkboard, place the candle in the box, and then light it.

In 1962 Sam Glucksberg modified the problem by offering a reward. He told some of the subjects: “Depending on how quickly you solve the problem you can win five dollars or twenty dollars. The fastest 25 percent of the subjects in your group will win five dollars; the fastest individual will receive twenty dollars.”

Adjusting for inflation, the amounts in today’s dollars would be approximately 40 dollars and 150 dollars. Now you might think that the reward made people solve the problem faster because they would win money. In fact, the opposite happened. People who were offered a reward performed worse than the subjects who were not offered a reward. How can we explain this? It turned out the process of turning the task into a competition can create stress in subjects, which can activate the stress response. Stress is good for running away from a wolf, but it undermines the ability to solve creative problems. This makes perfect sense: if a wolf is chasing you it’s the wrong time to think about poetry or creative projects.

How the Relaxation Response Works

In a word, the relaxation response (and techniques that activate it such as meditation, traditional yoga, Tai Chi, and the like) activates the parasympathetic nervous system, which includes the digestive system and the immune system. Studies measure immune system markers like inflammatory proteins, immune cell count, and antibody response. Their results confirm that mindfulness meditation can positively affect all of these by allowing the immune system to do its job better. The relaxation response also improves our ability to digest and absorb the nutrients we need to nourish and replenish our bodies. All this happens automatically when we just relax. But we do have some conscious control over the relaxation response.

Change Your Mind to Relax More

A simple but interesting study carried out by Abiola Keller and her colleagues at the University of Wisconsin suggests that having a relaxed attitude toward stress can reverse the harms that stress induces. The group examined the responses of almost 30,000 Americans to two questions from a previous study. These were:

- 1. During the past twelve months, would you say that you experienced a lot of stress, a moderate amount of stress, relatively little stress, or almost no stress at all?

- 2. During the past twelve months, how much effect has stress had on your health—a lot, some, hardly any, or none?

The people who answered “a lot” to the first question were more likely to have poor health outcomes. These people said they had a lot of stress and they were 43 percent more likely to die relative to the group who were not worried about stress. This is expected, given what we know about the stress response and its negative effects on the immune and other systems.

The surprise came when the researchers looked at people who answered “hardly any” or “none” to the second question. This group, which included people who said they had experienced a lot of stress, didn’t think stress was bad for their health and so were not worried about it. These participants had better health outcomes even than those who reported having very little stress. Being an observational study, we face the chicken-and-egg problem again: Did not worrying about stress lead to better health? Or did better health make people worry less about stress? And if you are not worried about stress, are you actually stressed? We cannot be sure what the answers to these questions are.

In her TED talk, health psychologist Kelly McGonigal does not refer to the chicken-and-egg problem with observational studies and claims that worrying about stress, rather than stress itself, is the fifteenth leading cause of death in the United States. The main study she uses to justify this claim is not definitive, but her overall message that we should stop worrying is a good one, because we have some control over it. Worrying rarely helps and almost always increases our stress levels. So it is important to take time every day to relax.

Takeaway: Inducing the Relaxation Response

One way to learn to relax is to follow in the Beatles’ footsteps and visit an ashram in India, but you don’t have to go that far. There are many options, including meditation, mindfulness, traditional yoga, Tai Chi, Qi Kong, and Benson’s method. I’ll describe an exercise I teach that is evidence based. All you really need is about fifteen minutes and a quiet space where it is safe to close your eyes. It is quite easy and will make you feel good right away.

Conscious Relaxation

This is how I do and teach relaxation. It is informed by my knowledge of the evidence for yoga. It is best to do this exercise lying down, but you can also do it seated. Take a few deep breaths or sighs and feel the tension in your body begin to let go. Prepare to squeeze and release muscles in different parts of your body. It is best to do this with your eyes closed, so read through it once, then do it.

- • Legs. Bring your attention to your legs. Take a deep breath in, and squeeze all your leg muscles. Hold your breath as you squeeze your thighs, hamstrings, calves—all the leg muscles. Keep the other parts of your body completely relaxed as you squeeze your leg muscles. After a few seconds, suddenly release your breath with a sigh and simultaneously release all the tension in your leg muscles.

- • Arms. Next, bring your attention to your arms. Breathe in, then hold your breath as you squeeze your fists and tighten all the muscles in your arms: your biceps, triceps, and forearms. Keep the other parts of your body completely relaxed as you squeeze your arm muscles. Then release your breath with a sigh and simultaneously release all the tension in your arm muscles.

- • Lower back. Then, bring your attention to your lower back. Breathe in, then hold your breath as you squeeze and tighten all the muscles in your lower back and your buttocks. If you feel strong you can lift your hips off the floor. Keep the other parts of your body completely relaxed as you squeeze your lower back and buttocks. Then release your breath with a sigh and simultaneously release all the tension in your lower back and buttocks. Drop your lower back to the ground.

- • Shoulders. Now bring your attention to your shoulders. Lift your shoulders up to your ears. Then push them as far away from your ears as you can. Then wiggle your shoulders around any way you want. Massage them into the ground. Feel all the tension from your shoulders and shoulder blades being released. Then take a deep breath in and sigh as you release the breath and relax your shoulders.

- • Neck. As you inhale, slowly turn your head to the left, keeping your whole body relaxed other than the muscles in the neck. You may feel the upper vertebrae in your back twisting. Hold it there for one more long breath, then as you exhale slowly move your head to the center, feeling all the tension in the neck release. Now repeat on the other side. As you inhale, slowly turn your head to the right . . .

- • Face and head. Moving your attention to your face and head, close your eyes, take a deep breath in, and squeeze all the muscles in your face. Squeeze your eyes together, squeeze your jaw. As if you are trying to move everything on your face toward the tip of your nose. Hold your breath for a few seconds. Then sigh out the breath and suddenly relax all the muscles in your face. Feel all the tension melt away. Feel your jaw relax, feel your lips relax, feel your eyes relax, feel your eyebrows relax, and feel your forehead relax. Feel your entire scalp relax.

- • Whole body. Now feel all your muscles and all your bones relaxing. Feel your body heavy, sinking into the floor or chair. Let your breathing relax. There is no need to worry about how deeply you relax, or how to relax more deeply. Simply enjoy any level of relaxation you are experiencing. Stay in this space for between one and ten more minutes, depending on how much time you have.

Eustress and the Zone

There is just one thing to add about the relaxation response: if we were totally relaxed all the time, we might not get out of bed. We need some stress to get things done. The problem is that most of us go too far and waste too much energy by getting much more stressed out than we have to. We need to regulate how much energy we use to minimize any damage done by stress, and we need to relax after our tasks so that stress does not linger unnecessarily.

During my first few years as a rower, I used to get so nervous before races that I was tired during the actual races themselves. Without knowing it, I was putting my body into the same state as the mythical caveman I described at the beginning of Chapter 5. Later I learned some simple relaxation techniques that helped me conserve my energy before the race. On very rare occasions, however, I was not nervous enough before a race, perhaps because I was tired or simply having a bad day. On these days, I had to learn techniques to lift my spirits. To perform well you have to get in the “zone.”

The zone was first described by Robert M. Yerkes and John Dillingham Dodson in 1908. They realized that to do important tasks some stress is required, but not too much. The Yerkes-Dodson law states that increased stress can raise your performance up to a point (this is eustress), after which it becomes counterproductive. Once we understand this, we can do things to increase our energy and stress levels or decrease them to make sure we stay in the zone.

When I talk to people about the zone, there is always one person in the audience who insists that lots of stress is very good for them because it helps them get things done. Other than situations analogous to fighting a wolf, I can’t think of any circumstances in which “beyond the zone” stress helps. And given the negative effect that being too stressed has on health, even if it were true that having lots of stress was good, it would only be beneficial in the short term.

In fact, many people who look relaxed are escaping from the various things they need to do. What might come across as outwardly lazy behavior can sometimes be exhaustion caused by busyness and stress. Of the thousands of people I’ve met in the twelve countries where I’ve lived, only one was totally relaxed.

He was a lovely Balinese man named Wayan, who was the main employee of a small hotel I stayed in for a week in a remote area of Bali. He would lie around in his hammock for most of the day. I think I saw him sweep the floor once very slowly. Whenever I told him I was ready for breakfast, which was included in the rate, he would smile, say yes, and remain in his hammock for a few more minutes before walking slowly into the kitchen. He would emerge an hour or so later with toast and some fruit. One hour to make some toast! If he was any more relaxed, he might have starved to death. Wayan might have benefited from a bit more stress. Most of us are not like Wayan and could probably benefit from techniques that help us relax.

We have to know how to relax and how to get “into the zone,” but not beyond it.

Takeaway: Getting into the Zone

There are many tools that can help you get “into the zone” or in a state of “flow,” and a lot has been written about how you can become an expert at this. The two I will share here are very simple, and while they are not enough to induce your peak performance, they can help a great deal. The first strategy is to make you less stressed if you are feeling too anxious (this is the one that is usually needed), and the second one is to get you ready if you feel sleepy and not stimulated enough.

- 1. Reducing stress if you are too anxious. The best way to do this is with breathing exercises, such as the slow breathing exercise in Chapter 4 (see here). If you feel too anxious, you can do this and your anxiety will decrease. Do it until you feel like you are back in the zone. Another easy breathing exercise is to sigh. Take a deep breath in, then hold the breath for as long as is comfortable. Then release the breath with a deep sighing sound.

- 2. Giving yourself a kick start if you are not anxious enough. For me this is rare, but it happens sometimes. Again, an easy way to pick up your energy levels to get you in the zone is with the breath. But this time, instead of slowing down the breath, breathe in and out deeply a few times. You may need to do it more than three times to feel your energy levels rise. If you do too many, you may feel light-headed, so start with just a few.