How could you say such a thing?” Clarita demanded of Sylvia that night when the two were alone.

“What?” Sylvia pretended.

“That Lyle might be Armando’s son.”

“He might.”

Clarita grasped for indignant words. She found only these: “He looks exactly like the cowboy, you’ve said so yourself.”

“He does have brown eyes, though, like Armando—”

“Loca! That’s what you are. Tell me! Where did Lyle get his height? Not from you—and certainly not from that baston … that squirt.”

“My father”—Sylvia chose the tall man she had seen at Eulah’s funeral—“was tall and handsome.”

“Lyle is the cowboy’s son!” Clarita asserted, and crossed her arms over her bosom, firmly, to emphasize her declaration. “You know that, too.” She had begun rehearsing the entreaties she would have to make later to the Holy Mother to yank Sylvia away from this terrible charade.

“Oh, I don’t know. I don’t know everything—like you, Clara.” Sylvia started to walk out of the room. “All I know is that he might be Armando’s son. Have you forgotten?”

“No, I have not forgotten all the crazy things you did,” Clarita said. “But nothing as crazy as what you’re doing now. You don’t fool me, Sylvia. You want to come between him and that beautiful girl—”

“Oh, do I? Do I?” Sylvia challenged Clarita with a cool look.

“—and she is beautiful,” Clarita extended her accusation, “perhaps as beautiful as you when you were her age, and that too is the reason that you—”

Sylvia turned around, ferocious. “How dare you!”

Clarita could no longer withhold these words. “You have to face that you’re never going to be—” She couldn’t finish.

“Miss America,” Sylvia whispered, so softly she seemed not to have spoken at all. She placed one hand on her hip, held the other out lightly, as if to initiate the royal walk. “I would have been Miss America.”

Clarita relented. “Yes, I’m sure you would have been.”

Sylvia smiled, accepting the words graciously; but then she thought of Eulah, and her curse, and of Lyle the First, who had left her so easily—who had confirmed the curse of a miserable life! “Eulah was right,” she gasped, “I was sinful, and I’m being punished for it; all I was for the cowboy was flesh to lust after—that’s why he could discard me like he did, the way Eulah knew.” She frowned, brushing away at something she felt on her shoulders, something clinging there.

“Are you ever going to let that crazy woman leave you in peace?” Clarita wondered. “Are you ever going to leave her?”

Sylvia Love shook her head in bewilderment.

For days she stayed mostly in her room, coming out in a long robe that concealed her body; she pecked at delicious food that Clarita fixed for her, all her favorites. Clarita would try to coax her appetite by announcing her most delicious delicacies: “Tomatillas, arroz con pollo, empanadas.”

Lyle watched Sylvia as she walked by him like a ghost, touching him on the shoulder, as if to assert that she wasn’t a ghost. To Lyle it seemed that way: that she was a ghost of Sylvia Love, of his mother, whom he loved and suffered for, so much, and who was becoming more and more of a mystery to him, the more he longed to understand her.

Clarita knew that Sylvia kept papers—perhaps only mementoes—gifts from Lyle the First?—in a wooden box in her bedroom. Clarita was, it must be understood, not a curious woman; she respected people’s privacy; she would never have thought of rummaging through that box—

Except that she needed to know!

She pulled out the box. It was not locked, and so what harm was there in looking? She opened it. There was a note from Lyle the First, when had left Sylvia. … Within its fold something dusty, umber—the crushed petals of a white rose?

And a newspaper account:

The Alamito Gazette

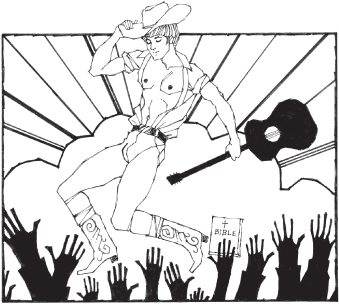

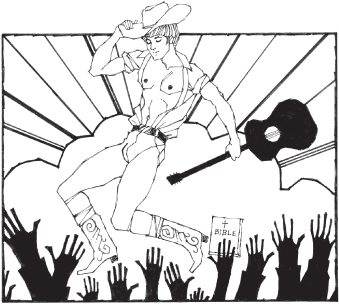

HOWLER AT MISS ALAMITO BEAUTY PAGEANT!

An enraged woman claiming to be the mother of Sylvia Love, a contestant for the Miss Alamito County Beauty Title, stole the show last night when she rushed onstage brandishing a Bible and then threw a sheet over her daughter during the bathing suit competition. According to others onstage, the contestant’s mother shouted a series of curses at her daughter for exposing her body. Miss Love attempted to flee the stage but tripped on the sheet, creating a scene that could have come out of a slapstick comedy and that was greeted with howls of laughter from judges and spectators alike, a hilarious commotion that must have lasted 15 minutes, during which Miss Love continued to struggle with the sheet, stumbling over and over, causing gales of laughter each time, until she managed to leave the stage. According to one judge, Miss Love impressed the panel during the talent competition, when she “sang ‘Amazing Grace’ very sweetly,” and when she said her first wish would be “to banish meanness from the world.” According to this judge, right up to the time of the uproarious intrusion, Miss Love was the leading contender for the title that would have taken her to the Miss Texas competition and eventually might have earned her the Miss America title.

There had been more than a chance of Sylvia’s winning the title. Oh, the heartbreak of it all! She had kept the vile account because it affirmed that she might have won. … Clarita was about to locate the newspaper clipping exactly where it had been, along with the ashes of the rose, when, through her tears, she saw what she was looking for: Lyle’s birth certificate.

Footsteps. Dios mío! It was Sylvia, coming home early, as if she could not cope with anything other than her sorrow and her anger, and her increasing “nips.” Clarita put the birth certificate in her pocket and dashed out of the room.

It wasn’t Sylvia who was returning. It was Lyle. Ordinarily she would have known that. Lyle made a distinctive sound as he walked in, his bootsteps soft for such a tall young man. Only her fear of being caught going through her things made her believe it was Sylvia.

“Clarita! You look scared.”

“No! Relieved!” Clarita said. “Because I’m going to give you evidence you need so you can go on with your sweetheart.”

“My sister—” The words had come unwanted.

“She’s not! Look.” She shoved the birth certificate at him. That would end it. Sylvia would have had to give the cowboy’s name as the father.

Lyle looked at the paper. He frowned.

“What?” Clarita grabbed it back and looked at it for the first time. She read the entry for Father: Unknown.

And Lyle’s name had been entered as Lyle Love.

Lyle was sadder than he had ever been, sadder than he had ever imagined he could become, so sad that he wondered, whether, without knowing it, he had always been sad. Of course, there were intervals of joy, but only now could he compare his greater sadness with his earlier state.

If Maria was his sister—

That was it, cut it out!

She wasn’t his sister. Still, she hadn’t been at school the day after the confrontation with Armando and Sylvia when she had run out crying, “Oh, God, oh, God, oh, God! Incest!”—and so he didn’t know how she would react to him, whether she had changed toward him, or would gradually.

He lay on his bed in his room, his guitar across his stomach. Try as he might not to, he felt enraged at Sylvia for announcing that he could be Armando’s son, and then in a moment pity would wipe away the anger, which would surge again.

“What’ll I do, Clarita?” he asked her when she came into the room to “teach him history,” although her lessons had all but stopped some time back. She had come here only to talk to him.

“Sylvia, beautiful Sylvia, your mother, is a sad woman, she never recovered from the dual loss, that son-of-a-bitch cowboy leaving her and—”

“What?”

“Ay, Dios mío.” She had slipped.

“Tell me what you were going to say!” Lyle coaxed her silence, because she had zipped her lips shut.

“Nothing, nothing!” It would be selfish of her to relieve the pain Sylvia’s secret caused her. “I was only going to say her suffering doubled, that’s all, when the cowboy left her.”

“He is my father,” Lyle asserted. “Isn’t he, Clarita? Maria isn’t my sister. The cowboy is my father—not Armando—isn’t that right, Clarita, isn’t it?”

“Of course!” But, oh, oh, she thought, Sylvia’s confused even me.

Unable to keep anger from his voice, Lyle said, “I’m going to talk to Sylvia, I’m going to ask her a lot of things.”

Lord God! Blessed Virgin Mary, look down upon us in these moments of woe. That was all Clarita could pray for now, although there was more to contend with: The Pentecostals were back in Rio Escondido for the Gathering of Souls.

That very evening, Lyle asserted his resolve to speak to Sylvia as soon as he came home from his job. Knowing what was about to occur, Clarita fled to her room, intending to say a full rosary while that encounter occurred.

As if she had been waiting for him—she often did—Sylvia walked toward him as he entered. He had intended to talk to her when she had not been drinking, but that was impossible now. “Sylvia, there’s some questions I have to ask you—”

“Don’t ask me anything! Nothing. Don’t ever question me!”

She turned to walk away from him.

“Sylvia! I have to talk to you. Why did you say that I could be Armando’s son?”

She whirled around. “Because you could be!”

“You’re lying, you just want to—”

“Didn’t you hear me? Don’t ever question me! Don’t you understand what I said?”

“I don’t understand you at all, Sylvia.” He felt only anger now. “Nothing you do makes sense. Nothing!” He relented. “Why, Sylvia, why did you do stuff like that?”

Anger smeared her face. Her lips parted, about to shout fierce words. Then her shoulders sagged and her lips closed.

“Why, Sylvia?” Lyle pled.

“You can never understand.”

“Never … understand?” Lyle whispered to himself.

“Never,” Sylvia said. “You can never feel what I’ve felt. You can never understand.”

“Am I still pretty, Lyle?” Sylvia asked her son. She stood unsteadily in the pose she would have adopted after she would have been named Miss America. Might still be? After all, she was only thirty-seven, and—

The sad wistfulness of her once-familiar question—withheld for long—swept away all the anger Lyle had gathered in the past days. “You’re more than pretty, Sylvia,” he said. “There’s no one more beautiful than you,” he added, because she seemed more desperate than usual to be assured.

Sylvia touched the smile on her face, as if to assure it was there and that he would see it. She stumbled, holding on to the staircase.

He led her to her favorite chair in the living room. “That’s what the cowboy said, that I was the most beautiful woman—and then he left me.”

“My goddamned son-of-a-bitch father shouldn’t’ve done that, he was wrong to do that,” Lyle said.

“How wrong was he? Tell me.” Sylvia almost didn’t recognize her own voice, that’s how husky it had turned. Sitting on the chair Lyle had bought her when she complained that she had to sit on the bed of her apartment to watch television—and remembering that time—she closed her eyes and touched her breasts briefly, remembering, remembering, the way the cowboy who made love with his boots on used to touch them—remembering—his long, lanky body lying next to hers and—remembering—how he would throw off any covering, even when it was cool.

“My goddamned father was real wrong to leave you.” Lyle seldom thought about the fact that the cowboy had also left him. He hated him for what he had done to Sylvia. For him, he was an absent presence. “I bet he regrets leaving you, regrets it every goddamn day of his goddamn life.”

“Regrets? Oh, yes, tell me how much he regrets—“ Her eyes still closed, Sylvia leaned back on the chair. She swallowed from the bottle on the table beside her chair, long swallows, welcoming a warming haze, a warm, dark haze. “Come over here and tell me, tell me about regret.”

Lyle moved toward her, thinking she was falling asleep. He reached to take the bottle gently from her before it fell to the floor.

She grasped his hand, held it close to her, to her chest.

He looked down at her, puzzled.

“Go ahead, go ahead and tell me,” she sighed and kept her eyes closed, and parted her lips to Lyle Clemens the First, who was there now within the darkness her shut eyes had converted into a warm night, who was back, full of regrets for leaving her. He stood there, in the soft darkness of her memory—Lyle the Cowboy, Lyle the First, yes, he stood there, within that blur of her vision, a blur that gradually cleared within the sealed darkness, and, yes, he stood there, oh, yes, becoming clearer, taking full form within that gentle darkness, stood there so tall and handsome, and she held his hand to her chest. “I love you, Lyle,” she sighed.

Lyle was startled, not by the words—his heart clasped them eagerly—but by the knowledge that she had never spoken them before. “I love you, too—“ He longed to say, “I love you, too, Mother,” but must not. “I love you, too, Sylvia.”

“Kiss me, Lyle,” she said to the man who had finally returned after all those years of her waiting.

Lyle tried to ease his hand away, kindly, from her increasing grasp.

“Kiss me, Lyle.” When he did, it would all disappear, all the cruelty of long years, the memory of a single white rose, of a brutal letter.

Lyle bent over and kissed her on the cheek, lightly.

“Lyle—” she said to the man who had left her, and had returned, the way he did often in her dreams, but she was awake now and he had come back to tell her he loved her, couldn’t live without her, and he had just kissed her, the way he did, lightly before they made fervid love, and so she held his hand gently, guiding it to her breasts so that again she could feel him making love to them, could feel his mouth there, the moisture of his tongue, and then afterwards, they would—

He would—

She would—

Lyle yanked his hand away.

Sylvia opened her eyes. “Oh, my God!” she screamed.

Lyle staggered back.

“What the hell were you doing?” she shouted at him, at her son, who stood before her, where, only moments earlier, within the lucid darkness she had courted, Lyle the First had stood.

Lyle shook his head. “I wasn’t doing anything, you told me to kiss you, you—”

“Goddammit, how dare you accuse me? How could you even suggest that I—?” She brushed her body urgently with her hands, as if to push away the contact that had occurred, had almost occurred. Her body shot up, flung itself against him. Her hands lashed out at him, striking him over and over. “Damn you, damn you, damn you!”

When she released him, her body collapsed on the chair.

Mother, he wanted to say, but the forbidden word would not form. “Sylvia—” he said. “I’m sorry.”

“You can’t go there, it’s a pit of horrors,” Clarita told her when she realized that Sylvia was not only going to the Pentecostal Hall but that she intended to take Lyle. Clarita had thwarted this once before; could she again? The two women stood on the stairway, Clarita on the bottom landing, prepared to block Sylvia’s passage.

“I have to.”

“Why?”

“I have to face my sins.”

“Go to confession, then; speak to a priest.”

“It has to be there, at the Revival Hall. Get out of my way, Clara!”

“Estás loca!” Clarita retreated. She saw another woman now, a crazy driven woman. She had even dressed to look different, in a dress she had never seen before—Eulah’s!—loose, dark, and she was pale, even paler without makeup. The fact that she had been drinking all day and could still speak with such determination added to Clarita’s fears.

“It has to be there,” Sylvia spoke now as if only to herself, “where Eulah cursed my sinfulness, before she said I killed her, cursed my sinfulness for everyone to hear!” The words echoed in her mind, strange, dark, hers. “That’s where it has to be faced, for everyone to hear and know that I have sinned gravely, that I am being punished for my sins. There—and with Lyle.”

Home from his job and lugging his guitar to practice on later tonight, Lyle had surrendered himself to Sylvia’s demands that he must come with her. He did so, willingly, to be with her, wherever she needed to go, during this time of terror that was etched on her wracked face, emphasized by the drab clothes she wore. What had occurred, that earlier time between them, had mystified him, and he had not yet sorted out what exactly he had done, but he suspected that her urgent pleading that he come with her now had to do with that. Clarita had followed them for more than a few steps, pulling at Sylvia’s sleeve, shouting that she was surrendering her soul to hell by going to “that gathering of locos.” Sylvia had moved along, now silent, Lyle beside her as she hurried—at times stumbling and he helped her up—down the streets of Rio Escondido toward the Pentecostal Hall.

They entered the huge hall, swarming with hundreds of souls who had come from all around, as far as El Paso, as far as Albuquerque, a contingent from Dallas, another from Georgia, all forlorn, crying even when they smiled, young and old, men and women, children, their arms held out, hands reaching, bodies swaying—and a dog was running around under the seats howling in terror to the cacophony of hallelujahs and praise-Gods.

Television cameras scoured the auditorium, electronic eyes glaring at the audience, capturing the most enraptured, the most tortured.

Against the backdrop meant to suggest a rectory but looking more like a room in a gaudy motel—a happy picture of Christ in resplendent robes pasted against a wall—a gray-haired preacher jerked about, shaking and thrusting, then walking backward in short, jerky steps, then hopping forward, ranting unintelligible words punctuated now and then with a shouted, “Do I hear an amen?”

“Amen!” Near the gray man, and dressed in frilly ruffles and wearing a huge blond wig, his wife shook and shook, her formidable breasts about to pop out of her red-ruffled blouse. Every time the gray man paused to gasp, she slapped her tambourine and interjected: “Hallelujah, praise Jee-zuss!”

Sylvia recognized the gray man and the blond-wigged woman who had hovered over her dying mother years ago. How was it possible that Sister Sis had not changed during that long interim?—no; she had changed, had camouflaged her age with even heavier makeup. Brother Bud had only grown grayer.

A chorus of black and white men and women in robes hummed over it all. Apart from them—as if purposely separating herself and wearing a much more regal robe than theirs—was an imposing, heavy black woman with a glittery gold crown.

Attempting secretly to loosen his tight corset to allow freer struts as he hip-hopped back and forth, Brother Bud waved a Bible in one hand and clutched a microphone in the other.

“Let’s hear it for the Lord-uh!” He bumped at each “uh!” “Do I hear an Allelu-jah-jah!” He bumped twice.

“Allelujah!” “Allelujah!” “Allelujah!” the audience screamed. “Tell it to us, Brother Bud!” … “Tell it like the Good Book says.” … “Cast Old Satan back into the Pit!” The congregants waved their hands to intercept the preacher’s words, then clasped them to their hearts, to bury them there.

Shaking, swaying, Sylvia pitched herself into the enraged spirit of the congregation.

Lyle clenched his guitar, as if the greedy fingers about him might tear it away, fingers that seemed to be scratching at the air. He glanced at his mother, and then away from someone he had not seen before, a strange agitated woman clawing at the air like the others here, her eyes closed, lids quivering.

Brother Bud shouted, “Take sides, all you who hear the Word, for the time is at hand and those who wait shall find no salvation out of the flames of hell!”

“Praise God’s harsh judgement on those who do not repent!” Sister Sis joined. The mountain on top of her head did not budge.

“Amen, amen!” … “Praise Jesus!” … “Tell it to us, Sister Sis!” screamed the congregation.

“Give and it shall be given to you,” Brother Bud said, jack-hopping forward, then back. “Give as he has given to you.”

“Let your gifts match your abundant love for him!” Sister Sis spoke into her own microphone. Tears streaking her cheeks sparkled with unglued glitter. Then her sobs broke into girlish giggles that she muffled by jiggling her tambourine.

Glaring at her, his heavy gray eyebrows entangled into a frown, Brother Bud intoned, “Give, give, give!”

The congregation responded, plopping bills, coins into baskets passed among them by somber attendants who looked like morticians.

“Let’s hear it for the Lord!” Brother Bud accepted the largesse.

Lyle saw the black woman with the crown shake her head.

“Now come, shed your sins, give yourselves up to the Lord. Come!” Brother Bud summoned.

“Be saved, be healed! Be slain in the spirit!” Sister Sis beckoned, between sobs.

“Cleanse me!”

Who had screamed that out so violently? It was Sylvia—no, a woman Lyle tried to recognize as Sylvia Love, his mother, a woman with her hands raised tearing at something invisible that must be brought down. Lyle tried to hold her hands, coax them back down. But her body, every limb, was rigid.

From all over the hall they rose, some quickly, some slowly, some shoving away others, some hesitant, being shoved, some ambling along on crutches, others running, others pushing quivering beings on wheelchairs, all flowing in a tide of pain toward the stage, where Brother Bud, flanked by four husky guards in suits, awaited the approaching procession.

Sylvia took Lyle’s hand. He surrendered it to her.

Brother Bud shoved his palm against the head of each congregant begging salvation. “Be cured!” … “Speak!” … “Walk!” “Be slain in the spirit!” Each fell back, cradled by the attendants. “I can walk!” … “I can see!” … “I can hear!” They trudged and crawled and ran, to applause and hallelujahs—and to the maddened tinkling of Sister Sis’s tambourine.

Lyle marched forward with Sylvia, clutching his guitar. He would walk with her, stand with her, help her. Whatever she needed that might break the terrible sadness that drenched their house, he would try to provide. He moved, close to her, protecting her, breathing the heavy stench of alcohol that had become her perfume.

No question about it. The black woman with the crown was glowering fiercely. At him? At Sylvia?

“Lubyah misque ilyalon!” Brother Bud lapsed into tongues at the enormity of his miraculous cures—and more to come. “Not my cures, the Lord’s,” he had asserted to applause.

Lyle echoed the sounds he had just heard—“Lubyah misque ilyalon.” He located his guitar in front of him. “Lubyah misque,” he repeated, “ilyalon—lubyah misque ilyalon.…”

Sylvia surged forward, those in her path parting to let her pass.

Now she stood with Lyle before Brother Bud on the stage. Sister Sis moved in for a closer look at Lyle. She shook her tambourine and cried, “Lord, Lord, Lord!”—and slapped her thighs spiritedly.

Lyle felt the stare of the black woman on him. “Uh-uh,” he heard her say in loud disapproval. “Uh-uh.”

“Hmmmmmm, Lord, hmmmmmm—” the chorus translated.

Sylvia looked beautiful in this light, the shadows that liquor and pain had dug into her face absorbed by the cleansing glare of light.

Sister Sis held her gaze on Lyle and made a loud smacking sound with her lips, accompanied by several jiggles of her tambourine.

“Uh-ummm.” This time, Lyle was sure, the black woman’s harsh disapproval was being directed at him—or Sylvia.

“Hmmmmm,” the chorus sang.

Sylvia Love grabbed the microphone extended to her. “I am here to be purged of my grievous sinfulness!”

“No, Sylvia!” Lyle protested. He turned, now entreating, toward the woman with the glittery crown, as if she might help them. She only shook her head in even more emphatic disapproval.

Sylvia Love shouted: “Cleanse me!”

Before the readied palm of Brother Bud could strike her forehead, Lyle plucked an assertive chord on his guitar—stopping the motion. Another chord, another. “Lubyah misque,” he sang the weird words he had memorized. “Lubyah ilyalonnnn—lubyah misque—” He struck more chords, sweeter ones, and then—thinking of Sylvia there beside him, trying to punish herself in front of all these people, and for God-knows-what—he plucked sad notes, sadder ones, and sang, “Lub-yah mis-que il-ya-lonnnn!”

“The Lord’s Cowboy is singing in tongues!” The excited word spread through the congregation.