3

WATER OF LIFE AND DEATH

The baptismal font near the great west door of Salisbury Cathedral

Entering Salisbury Cathedral today from the great west door, the first thing you encounter in the nave is water. It is a baptismal font, or, rather, a fountain, a broad bronze basin in the shape of a cross, brimming with water which pours unceasingly from each of its four arms: on the surface mysteriously still, yet constantly overflowing in its promise of renewal.

There is great significance in having water at the entrance to this cathedral, for in Christian theology the water of baptism serves as the door through which every Christian enters not just the faith but the whole Christian community, past, present and future. For the Bishop of Salisbury, Nicholas Holtam, the baptismal waters are the very ‘water of life’ itself:

They purify us. It’s about the journey to the Promised Land, passing through the waters of the Red Sea. We come out the other side of the font, as it were, and into the nave of the cathedral, where the community gathers to celebrate the Eucharist. We’re called individually, but we gather together. And this is about the whole church, not just this cathedral. Becoming a Christian, you are baptized into the worldwide church so that, belonging here, you belong in all times and all places.

It is of course not only in places of Christian worship that you are likely to be greeted by water. ‘You who are faithful!’ enjoins the Qur’an, ‘When you undertake ritual worship, then wash your faces, your hands to the elbows, rub your heads, and your legs to the ankles.’ The need to wash before prayer, before the individual joins the community in the face of God, has determined the architecture of the great mosques, where substantial spaces for ablutions have to be accommodated, and the provision of fountains and baths has helped to shape the urban geography of the Islamic world.

Water to prepare the body for the activity of the spirit, water that readies humans for a new relationship with the world: it is an idea that chimes so strongly with everyday experience that it is, unsurprisingly, central to many faiths. In modern Judaism, as in ancient Egypt and in classical Greece – indeed all round the world – water plays a central role in religious practice, cleansing both body and spirit, and helping define the community. Sometimes water from a particular source is especially revered. Muslim pilgrims to Mecca will try to bring back in special bottles water from the Zamzam spring (see Chapter 14), which at God’s command started flowing to slake the thirst of Hagar and Ishmael: it is kept for special moments, and may be pressed to the lips of the dying. For Jews and Christians the waters of the River Jordan, in which the prophet Elisha ordered Naaman to bathe and be cured of his leprosy, and in which Jesus was baptized by John the Baptist, have a particular significance. The British monarchy to this day uses Jordan water for royal baptisms. Roman Catholics all over Europe accord special properties to water carried home from Lourdes. But for no faith does water, and a particular water, play such a significant role as for Hindus.

In a South Indian painting of around 1900, in front of a row of improbably coloured trees, we see four people standing in a river, which is here rendered as a two-dimensional ribbon of vivid blue, inhabited by a crocodile, a turtle and fishes. The three figures on the right, a man and woman with a child between, are being addressed by a blue, diabolic figure on the left: clearly two worlds are in uncomfortable dialogue. The composition and style are simple and bold, some might say crude, which is to be expected, because this is just one of a set of sixty paintings designed to accompany a popular story-telling performance, not unlike a puppet theatre, somewhere between public entertainment and community worship. The story it tells, found in the Mahabharata and other Hindu scriptures, is one of India’s best known morality tales, still popular today.

Its main character, the legendary King Harischandra, was famed across India for always telling the truth and keeping his word, no matter the cost. The plot has echoes of the story of Abraham and Isaac, and perhaps even more of Job. As a test, played out in front of the gods, the rich and powerful Harischandra is stripped of power and wealth, and subjected to dreadful ordeals to see whether his integrity can be broken. Our painting shows a critical moment in the narrative. Harischandra and his family have come on pilgrimage to the city of Varanasi, to bathe in the holy waters of the Ganges, which is where we see them. But, even here, an evil emissary, the blue figure on the left, pursues them with threats. In order to honour a promise to pay a large sum of money, the king will soon have to sell his wife and only son into slavery, and himself to work as a lowly attendant at a cremation site on the banks of the river. At the very moment when – rather than fail to keep his word – he is about to kill his wife and cremate his son, the gods restore both of them to him, and invite him to take his place among the divinely blessed. Goodness is rewarded and all ends well. Gandhi claimed that this story, which he heard as a child, did much to strengthen his belief in the absolute power of truthful integrity.

South Indian painting, from around 1900, showing the story of King Harischandra with his wife and son bathing in the Ganges at Varanasi

It is no surprise that the climax of the story, the ultimate conflict of good and evil, of life and death, takes place by the Ganges in Varanasi, because the water depicted in this painting is like no other. Every morning there, you can see people standing, like Harischandra and his family, waist-deep in the Ganges. Facing the rising sun, they take the water of the river in their hands, hold it up, and reverently pour it back. And they do it because this river, says Diana Eck, Professor of Comparative Religion and Indian Studies at Harvard University, is the ‘river of heaven’:

Sunrise at the Harischandra Ghat at Varanasi on the Ganges, with bathers facing the rising sun

The Ganges is said to flow originally across the sky and in the heavens, in the form of the Milky Way, before coming to earth on India’s northern plains for the salvation of the souls of men and women. So the Ganges is actually a liquid form of the goddess Ganga. The river – the goddess – opens a channel of communication and of communion between heaven and earth. One could say that the Ganges descended to earth long ago, but in the powerful religious imagination of the Hindus, it continues to descend from heaven even now.

The water of this river which links earth to heaven, which is the goddess herself in liquid form, is revered by all Hindus, and those who make pilgrimage to the river usually want to take some of it home with them, just as Muslims do with the waters of Zamzam spring or Christians with those of the Jordan. To do so they have for centuries bought brass or copper jars – there are several in the collection of the British Museum – similar in shape to the three shown in our painting. But those who could carried more away with them; for possessing Ganges water in bulk has long indicated particularly high status.

The seventeenth-century Frenchman Jean-Baptiste Tavernier, who travelled widely in India, tells of Ganges water ‘brought from a great distance’ being drunk at a Hindu wedding: ‘for each of the guests three or four cupfuls are poured out, and the more of it the bridegroom gives, so he is esteemed the more generous and magnificent’. The Mughal emperor Akbar, the contemporary of Elizabeth I of England, even though a Muslim, saw unique virtue in the Ganges water which his Hindu subjects so revered: ‘His Majesty,’ reported Abul Fazl, ‘calls this source of life the water of immortality…Both at home and on his travels, he drinks Ganga water. Trustworthy persons, stationed on the banks of the river, dispatch the water in sealed jars.’

One of the huge silver vessels made for the Maharajah of Jaipur to carry Ganges water to London, where he attended the coronation of Edward VII in 1902

Akbar’s example was followed for centuries by the grandest of India’s rulers, few among them grander than the Maharajahs of Jaipur. So when in 1902 the then Maharajah was invited to London for the coronation of the new emperor of India, Edward VII, he arranged to take with him an ample supply of Ganges water. The result, which can still be seen today in the City Palace in Jaipur, are believed to be the two largest silver objects ever made. The enormous urns stand five foot three inches tall and weigh 345 kilograms. Each one of them can hold more than 2,000 litres of water: to get at it, you need a ladder and a ladle. These are vessels entirely worthy of their princely owner and their precious content.

It is somewhat anti-climactic to have to report that a modern Maharajah would have no need of such splendid silver jars. He could now arrange to have the water of Ganga delivered to him in London – or anywhere else – simply by ordering it online.

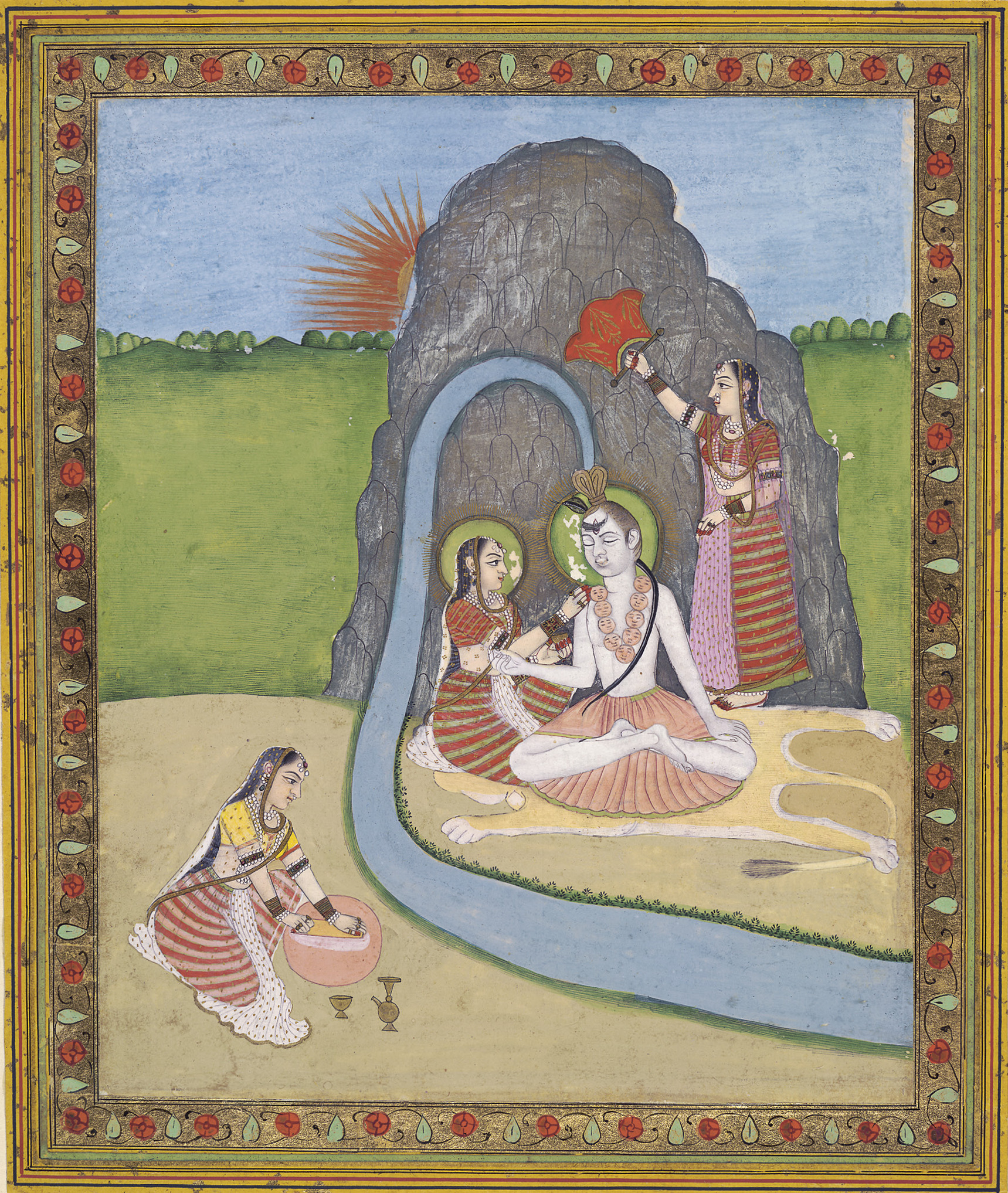

Ganga is poured from the heavens by the creator god, Brahma. Her turbulence is tamed as she falls through the hair on the head of Shiva, the god who – as we saw in Chapter 2 – destroys, transforms and re-creates. And then finally she comes crashing and tumbling into our world as the life-giving River Ganges, running from the Himalayas, south and east to the Bay of Bengal.

The River Ganga flows quietened from the hair of the god Shiva, in this gouache in the Jaipur style from around 1750

When she reaches Varanasi, however, the ever-changing Ganga turns north towards the fixed, unchanging Pole Star, back towards the place of her birth and her ultimate home. This makes Varanasi a tirtha, a crossing point, a place where two worlds meet, where heaven and earth are close. In such a place a transition from one to the other is particularly auspicious, and can most readily be enacted. So to bathe in the Ganges here, to cup its water in your hands and to let it fall again, to reverence the river with offerings of fire or rose petals, is to draw especially close to the gods. Diana Eck describes how:

What is accomplished by bathing in the Ganges is a kind of purity. It might simply be the purity of taking a bath every day, but it is also a washing away of what we might refer to as sin, or of those things that are polluting to us. And it also accomplishes the act of worship. When the water is taken up into one’s cupped hands and poured back into the river as an offering it is a form of worship. And Ganges is a place for worship on an enormous scale: it just so happens that this particular cathedral is a river.

It was to worship and bathe in the ‘cathedral’ of the Ganges that Harischandra and his family came as pilgrims to Varanasi. That our painting showing the scene, however, comes from south India, well over a thousand miles away is, for Diana Eck, not at all surprising. She argues that it is precisely such religious narratives and practices, widely diffused across the sub-continent over millennia, that have created what she calls the ‘sacred geography of India’.

India has a long narrative tradition of what constitutes the land in which people dwell. It’s told in story, in pilgrimage and in ritual. So the sense of this being a land in which people have a shared sense of belonging is very old. Most of all, it is the rivers that matter. They really are the temples of India. Long before there were temples constructed, the rivers were seen as sacred, and that continues in the daily rites of bathing that you see in a place like Varanasi. But Ganga is present not only in the waters that flow across this particular riverbed in north India, the Ganges. She is part of sacred waters wherever they are. One can bathe in Ganga almost anywhere in India.

For the non-Hindu, this is perhaps the river’s most remarkable quality. It flows, as everybody can see, through India’s north-eastern plain. But it is present – spiritually – in all the great rivers of India. Myths and legends tell how the water of Ganga is miraculously channelled into the major rivers of the west and the south of the country, turning them too in some measure into Gangas, binding the whole of the sub-continent together in this sacred geography, a shared reverence for Ganga, which is everywhere expressed through ritual and pilgrimage and stories told in all the languages of India. Thus the water of the Ganges has played a significant part in shaping the idea and the identity of India long before the era of the nation state.

The waters of Varanasi, however, do more than just cleanse you physically and spiritually, helping you to lead a better life. As Devdutt Pattanaik, one of India’s leading religious commentators, explains, they also offer you the perfect death:

South is the direction of death. The river dies in the south, so in India most of the crematoria are on the southern side of villages. The north, on the other hand, with the never moving, unchanging Pole Star, is the land of immortality. So when the river turns north, as it does at Varanasi, that stretch of water acquires special significance. This is the city of Shiva, the god who enables you to conquer death and enter rebirth, or to escape from the cycle of birth and death altogether. This is what makes Varanasi a place where people want to die. If I die here, I shall either be reborn quickly or I shall not be reborn at all, and so shall reach the blessed land which is free of both birth and death.

For Hindus, if you are cremated on the banks of the river at Varanasi, or if your ashes are brought there and surrendered to the Ganges at this special tirtha, you may at last be freed from the burden of the cycle of reincarnation: your soul will be liberated from all bodily constraints and can be reunited at last in everlasting tranquillity with the creator spirit.

This is why the river at Varanasi is lined with its famous cremation ghats, platforms to which bodies are brought all day, to be placed on the funeral pyres whose warmth you can feel as you pass at any time from dawn till dusk. One of the most sought after is still today called the Harischandra Ghat, where it is believed that the admirable king in our painting worked so humbly and behaved so honourably that he was at last rewarded by the gods.Although this is a place of death, of the obliteration of the body, there is little sign of mourning around the ghats – perhaps because everyone knows that soon all will be resolved by Ganga.

Funeral pyres at the Harischandra Ghat at Varanasi

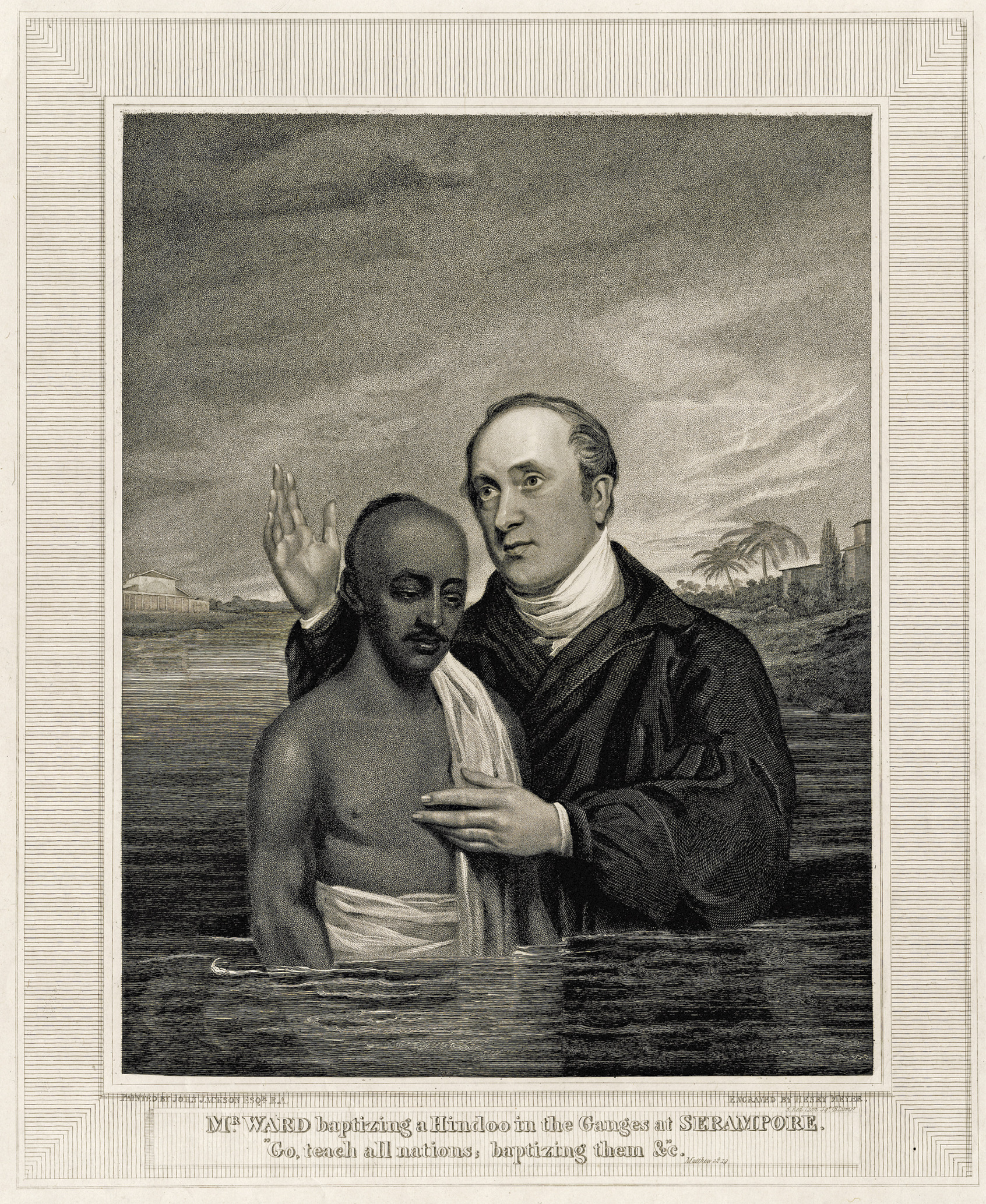

In the British Museum, you can find a striking illustration of the wide reach of this river’s power. It is a modest black-and-white engraving, and it too shows clothed people standing waist-deep in the Ganges. But here something very different is going on. A young Hindu man wearing a white dhoti stands with his eyes cast modestly downwards. Behind him, enveloping him with one arm while the other gestures towards the heavens, stands an Englishman from Derby, in full academic dress. We are witnessing an outdoor christening, in which the water of the Ganges is not now the binding element of India’s sacred geography but, as the Bishop of Salisbury explained, the initiation into a global Christian community through baptism. We cannot see from the print whether crowds are gathered on the banks of the river to witness the British Baptist missionary William Ward do his work, but a powerful demonstration effect was clearly intended. The print, published in 1821, has echoes, clearly conscious, of famous images of the baptism of Jesus by John in the River Jordan. Less subtly, the strident language of an English Baptist magazine of the day explains what is at issue: ‘Surely they need Christianity, who have…no better Saviour than the Ganges, no other expectation in death than that of transmigrating into the body of some reptile.’

The engraving is a vivid representation of the religious consequences of imperial conquest. As missionaries followed the expansion of British commercial and military power in India, the two cultures increasingly came into conflict, to the great irritation of the British civil authorities. Though successful conversions were rare, they worried about the political consequences for British rule of the missionaries’ assault on deeply held Indian beliefs. As we can see here, the sacred elements of one faith could become an exquisitely apposite point of attack by the other in the struggle for the conquest of souls. As the baptism proceeds, light begins to shine over an India long ‘dark’.

The Baptist missionary William Ward baptizing a ‘Hindoo’ in the Ganges at Serampore, 1821

But Devdutt Pattanaik reads the print quite differently, and in a much more relaxed manner:

Most Hindus would see no problem at all in being baptized and yet still following their temple rituals. There is no idea of conversion – of leaving a belief behind you. You just include another god, who might be helpful; and another ritual is always welcome. I see here a gentle Brahmin, wondering what this strange man is doing. The reverend, on the other hand, is trying to say that he has managed to get Brahmins on his side, and that eventually all Hindus will come into the fold.

Hinduism always exasperated and bewildered the West, because they just didn’t know how to make sense of its fluidity. At one time when the Indian penal code was being designed, the British colonial authorities wanted to find something for Indians to swear on as they testified. The Bible was used in Europe, but what should Hindus use? One answer the British came up with was: holy Ganges water. But, of course, in India no one looks at Ganges water in that way, so Indians would take the vow, and think nothing of it. You can imagine the British bureaucrats tearing their hair out – how were they to govern this strange country?

There is much about Ganga which still perplexes Europeans, especially watching the thousands of faithful who not only bathe in its waters, but drink them. Viewed from the steps of the ghats at Varanasi, they look, to say the least, uninviting. There is a fair amount of detritus – vegetable matter, plastic bags and worse – floating by, not to mention the other forms of pollution that cannot be seen. For many years, this dimension of the river has been ignored by the authorities of the Indian state. But as Diana Eck points out, that is now starting to change:

The high court of Uttarakhand in North India, where the Ganges and its sister river the Yamuna rise, declared early in 2017 that rivers have rights. They can be considered indeed as having the same rights as persons, so people can be punished for polluting them. It’s a fascinating thing: this is the first time that a court in India has given personhood to a river, both to the Ganges and to the Yamuna.

And it makes sense. The rivers of India, I think, are more important than most of the temples. So the fact that India does not have free-flowing, pure rivers is astonishing. They really should have a higher level of water quality than any rivers in the world because of the way they are used so intensively as ritual theatres. The purity and the health and the cleanliness of these rivers is not only a question of pollution in an age of rampant disease. This is a theological issue as well, and a very important one. We’re talking, after all, about the flowing waters of the body of the goddess.

The court’s judgment was subsequently reversed on appeal, but the debate about the rivers’ personhood can nonetheless be seen as a remarkable modern, secular engagement with an ancient Hindu belief.

The story of Ganga, the goddess who is one river and yet many spread across the sub-continent, is one of those points in religious life where the literal, the symbolic, and the metaphorical powerfully converge to shape the imagination of a people. Our popular, brightly coloured illustration of Harischandra, designed to accompany public story-telling, is a small but emblematic part of a centuries-old process that has contributed to the moulding not just of a religious community, but of the identity of India.

The first Prime Minister of independent India, Jawaharlal Nehru, stated in his will that he did not believe in religious ceremonies and wanted none around his cremation. But then this thorough-going unbeliever, who had ensured that the constitution of modern India would be resolutely secular, went on:

The Ganga, especially, is the river of India, beloved of her people, round which are intertwined her racial memories, her hopes and fears, her victories and her defeats…the Ganga has been to me a symbol and a memory of the past of India, running into the present and flowing on to the great ocean of the future…And as my last homage to India’s cultural inheritance, I am making this request that a handful of my ashes be thrown into the Ganga at Allahabad, to be carried into the great ocean that washes India’s shore.