9

LET US PRAY

Jean-François Millet’s L’Angélus painted in 1857 was widely reproduced. This engraving was printed in 1881.

O God, to whom all hearts be open, all desires known, and from whom no secrets are hid…(Book of Common Prayer)

I show you sorrow, and the ending of sorrow (Buddha)

In the name of Allah, in the name of God, the Most Gracious, the Most Merciful…(Qur’an)

O Great Spirit, whose voice I hear in the winds…(Native American prayer)

Holy Mary, Mother of God, pray for us now and in the hour of our death…(Roman Catholic liturgy)

Hear, O Israel: the Lord our God, the Lord is One (Torah)

At the beginning of the twentieth century, it was one of the most popular pictures in Europe and America. In a field, in the evening twilight, a man and a woman pause from the back-breaking work of harvesting potatoes, and stand in silent prayer. Millet’s L’Angélus, a celebration of traditional rural piety, was painted in 1857, and rapidly became an icon of French Catholic identity, reproduced in thousands of engravings like this one and in countless cheaper photographic versions. To national dismay, it was swiftly bought by an American, and then in 1890 acquired by a patriotic French collector for an enormous sum – 750 times the original price – and carried back to Paris in triumph. It hangs today in the Musée d’Orsay.

In the engraving you can see clearly the spire of the village church, where the bell has just been rung. It reminds everybody to stop their work for a moment and say the Angelus prayer, which invokes the angel who announced the birth of Jesus to the Virgin Mary, and who prays for all sinners. The Angelus bell did not – does not – call people to church: it calls them to stay where they are, but to redirect their thoughts away from their immediate everyday concerns and towards God. It is a public summons to a private act.

It is easy to see why this image of rural peace had such a powerful appeal for people living in the new industrial towns and cities, where factory work never stopped: by the time our engraving was produced in 1881, the tradition of the Angelus, indeed the very idea that you might be allowed to stop to pray in the middle of the day’s work, was to most Europeans living in cities at best a memory. But Millet’s picture struck another, perhaps even deeper, nostalgic chord. In the anti-clerical politics of the French Third Republic, which ultimately led to the complete separation of church and state in 1905, it spoke reassuringly of another France, as it had claimed to be before the Revolution of 1789 – a nation united and defined by its devotion to the Catholic faith (see Chapter 28). It is surely no coincidence that in another country that until recently defined itself in very similar terms – Ireland – the Angelus bell (in spite now of considerable public protests) still rings, on national radio at twelve noon and on national television at six in the evening.

In a similar way for millions of Muslims in Europe and beyond, the sound of the muezzin is also a regular, familiar part of life. Five times a day, Muslims everywhere pause for a few minutes, just like the Christian peasants in L’Angélus. They suspend the business at hand, focus their thoughts on God, and, wherever they may be in the world, all turn towards Mecca to perform the salah: the Islamic prayer ritual of reciting, standing, bowing, prostrating and sitting.

Much prayer of course takes place in the context of the weekly gatherings in synagogue, church or mosque. So it may seem odd, in a book concerned above all with belief as a communal enterprise, to concentrate here on an activity so highly personal as private prayer – each soul’s individual and complex quest for what the Anglican priest and poet George Herbert with sublime simplicity called ‘something understood’. Since this usually involves putting aside the obligations of everyday life for a little while, prayer may seem – from the outside, at least – to be a form of social withdrawal. But as the Angelus and the Islamic call to prayer demonstrate, what appears to be the most highly individualized of spiritual activities can also be a profoundly communal act.

We shall return to that paradox at the end of this chapter, but I want to begin with the more practical problem of how people prepare themselves to pray, especially when they are not gathered in a place of worship. Almost all religious traditions address this question of how to pray alone. It is a task with which most people need help, if only to overcome some of the unavoidable consequences of our humanity – that we have restless bodies and highly active minds, not quickly quietened; a desire for control and security, not easily relinquished; and a sense of our inner world as an enclosed space, into which it is rarely straightforward to allow the divine to intrude. So, how do those who wish to pray settle themselves? And, once settled, how do they then open themselves, so that they can not only speak, but listen?

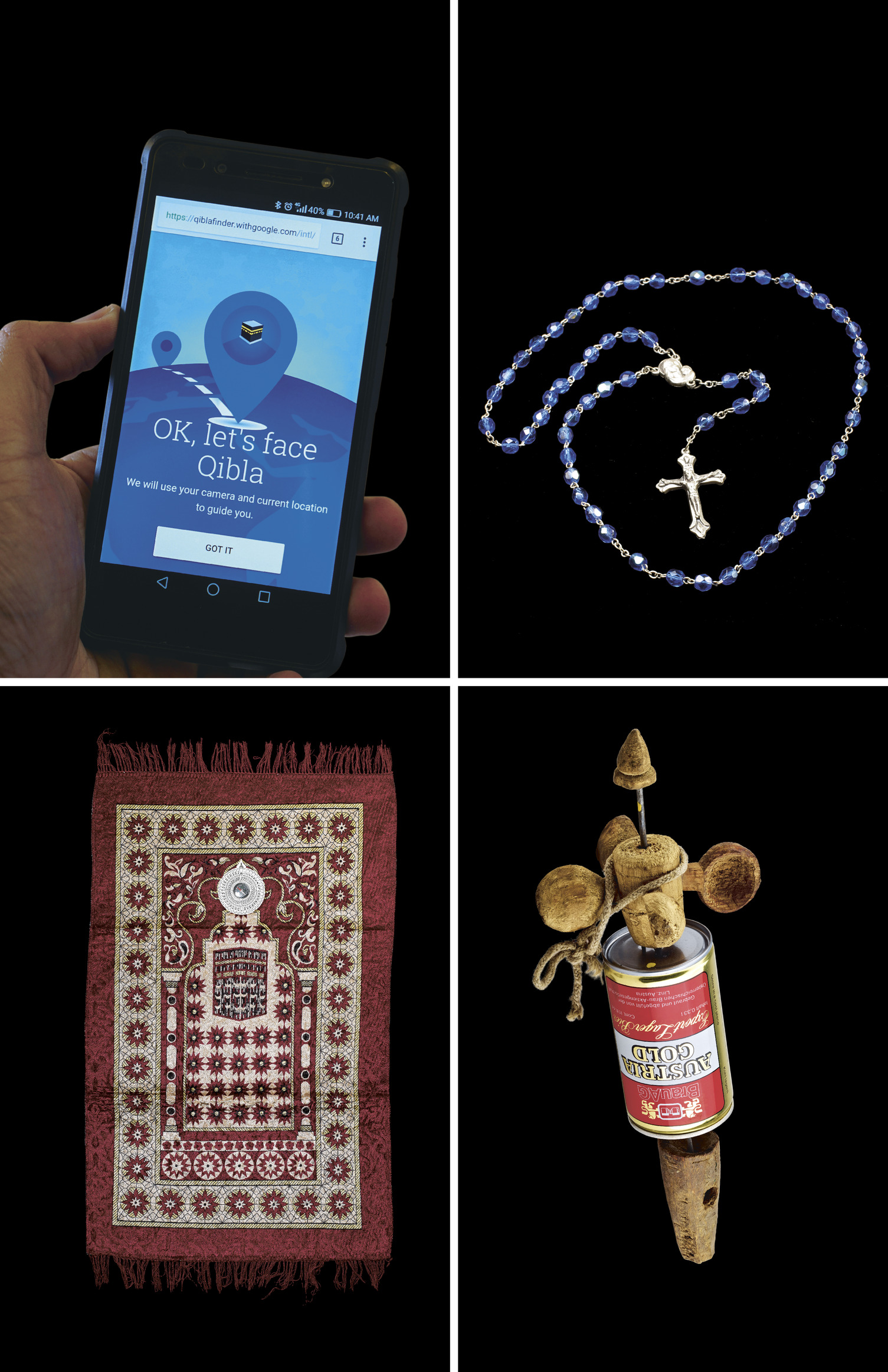

Aids to modern prayer: (clockwise from top left) qibla-indicator app on a smartphone; Catholic rosary beads; Buddhist prayer wheel from Kashmir made from a beer can; Islamic prayer mat from Saudi Arabia.

The best way to disconnect from our physical surroundings seems counter-intuitively often to be to focus on our physical body – our posture, our breathing – and then to use objects, such as prayer beads that we can touch and tell. It is those material objects that help, for a moment, to leave the material world behind. Some of them are beautiful and precious works of art made of box-wood and crystal, ivory and precious stones. But most physical aids to prayer have little aesthetic or commercial value – indeed some, like the Buddhist prayer-wheel designed to repeat mantras and prayers perpetually, can be made out of ostentatiously recycled materials that rejoice in their very ordinariness. Objects like these matter far less for what they are than for what they do.

For a Muslim preparing to pray, there is always one pressing question: how to know where to turn in order to face Mecca? To find qibla – the right direction – you need a qibla-indicator, and there are few more stylish than the one made out of ivory and gold in Istanbul in 1582 or 1583, now in the British Museum. It is circular, and looks like a slightly oversized powder compact. Under the lid, the lower disc is essentially a compass and a sundial rolled into one. Painted in the middle is a black cube, ringed with a red fence: it represents the Kaaba, the sacred building linked to Abraham and Muhammad, that stands at the centre of the Great Mosque in Mecca (see Chapter 14). The compass shows you where to turn to face both Mecca and the Kaaba, while the little golden sundial tells you when: if there is no muezzin within earshot, it will tell you the time for your daily prayers.

Ivory qibla-indicator with sundial, made in Istanbul in the late sixteenth century

Dr Afifi al-Akiti from the Oxford Centre for Islamic Studies explains:

Once you know you are facing in the right direction, you next make sure that you are in the right frame of mind. You clean yourself physically, and then perform the ritual ablution – what Muslims call Wudu. Then you go on to your prayer mat. Essentially you want to try to create a sacred space. It’s a bit like Aladdin going on to the magic carpet. You are the pilot, going through all the instruments to make sure you have done all the pre-flight checks. And once you are ready, then you can take off into prayer.

I think it is important to remember that for most prayers, the direction is not particularly significant. The Koran says: ‘to God belongs the east and the west, and no matter which way you turn you shall find the presence of God’. The famous theologian Al-Rumi said: ‘I looked in temples, churches and mosques but I found the divine within my heart.’ So the direction itself is important only for this form of regular daily prayer called the salah, the formal liturgical prayer designed to give a sense of unity. But the internal prayer itself has to take place within your heart. It is not bounded by time or space.

Dr al-Akiti, like all Muslims, has his qibla-indicator and his prayer mat to orient his body and direct his prayer, although modern technology means that many Muslims now have an app on their smartphone that tells them immediately which way to face.

For Sri Lankan Buddhists, as Sarah Shaw from the Oxford Centre for Buddhist Studies describes, the helpful object to settle the spirit and focus contemplation is more likely to be a small pottery bowl that costs just a few rupees, and can serve as a lamp: lighting this is a way of paying respect to the statue of the Buddha, as representative of the fully awakened mind. To activate it requires only some butter or coconut oil and a few strips of torn cotton:

If you tear a little bit of cotton and twist it in opposite directions, then at some point the tension in the middle becomes so strong that it makes a kink in the cotton and becomes a wick, which will last for a long time. In Sri Lanka, they say that a wick like this, formed by such tension, is an embodiment of the middle way of the Buddha, the middle point between two extremes – and so a pointer to enlightenment. Lighting the lamp is a profound ritual, earthing, tranquillizing and very satisfying, as rituals often are. Symbolically, it is of course the light that dispels spiritual darkness.

Butter lamps burn beside the hand of the Buddha.

This paying of respects at the outset of prayer involves what Buddhists call ‘taking refuge’: you must first of all put yourself under divine protection. It is an idea found also in Muslim prayers, which often open with the words ‘In the Name of Allah, the Most Gracious, the Most Merciful’. And Brother Timothy Radcliffe, a Dominican monk and theologian, tells us how there is a comparable process at the outset of Roman Catholic prayer:

We begin by making the sign of the Cross in the name of the Father, the Son and the Holy Spirit. That is placing ourselves inside Christ. Christ isn’t just somebody that you address, He is somebody you inhabit, in whom you are at home. Then it is very important that your body be well placed. We are animals, rational animals, and so it’s very important, if we are to pray, that our bodies should be well rooted, well seated, breathing well. When you read books of theology, it’s often so abstract. In fact it is about getting down to earth, to our physical body as it lives and breathes.

Once the body is settled, the next impediment to concentrated prayer is the wandering human mind. For Sarah Shaw, as for Timothy Radcliffe, breathing is the starting point: we can manage our breathing consciously, but we can also relax and simply let breathing happen:

This is actually necessary for meditation, necessary if the mind is to be fully engaged in thought. It is often compared to a bee going to a flower: it knows where it wants to go, but it also needs to circle around and get to know the flower again and again and again and again. When you repeat a chant or a little mantra, you’re simply allowing that very discursive, dispersed part of the mind to come together, to unify, and to settle on one object. So I find chanting very helpful, because that part of my mind which is always engaged during the day – like a bee buzzing everywhere – has a chance to settle on just one flower.

But as anyone who has attempted it will attest, reaching and sustaining this kind of focus is a great deal more difficult than it might sound. So it is perhaps not surprising that most faiths have developed repetitive forms of prayer, part of whose point is to assist the journey into concentrated stillness.

It is often, according to Timothy Radcliffe, a journey sustained by stringed beads or rosaries:

I think in Islam, Buddhism and Christianity, you find at some moment there is the presence of beads: we tell our beads, we count our beads. It’s a very tactile act, accompanying the process of moving through prayer. I think as bodily beings we need physical practices like these which penetrate the whole of us.

In the early centuries of Christianity, prayer was thoroughly physical, as with prayer rituals in Islam today. People stood, they bowed, they prostrated themselves, they genuflected, just as Muslims still do. But in the sixteenth century prayer seems to have become more mental, more abstract. The Puritans banned all dancing and singing, and we lost a lot of that bodily dynamism of our prayer, which Muslims – I think wisely – have retained. In the Catholic church this is something we are now trying to recover.

Passing from one bead to another, we pray with our fingers and our body. The rosary helps calm the spirit by repetition: the beads lead you through the cycle of life, in ten Hail Marys, which begin by addressing her at the moment she conceives Jesus, and end by asking her to pray for us in the hour of our death. And then there is a larger bead, for the Our Father. The repetition of the familiar prayers is a very effective way of letting go of the worries of the moment.

Dr al-Akiti finds a very similar practice – with a very similar intent – in many Islamic traditions:

In some circles you can hear just a single syllable – hoo, hoo, hoo, hoo – which is to be recited a hundred or a thousand times, to help you to meditate. According to the Qur’anic tradition it is only through remembering God and meditating that you find peace and contentment of heart.

This kind of repetitive prayer can be performed anywhere, in private or in public. It may be done alone, or in informal groups, and crucially it needs no priest or imam to direct it. It is an activity of the laity. Yet in both the Christian and Islamic traditions, what is striking about the regularly repeated individual prayers – of the rosary or of the salah – is that they are never about the individual: they define the person praying as unequivocally a member of a community. When single Muslims pray, they unite with Muslims in every place, as all turn towards Mecca. The two peasants in the fields in Millet’s L’Angélus are joining everybody in the village praying at the same moment. The opening words of the Lord’s Prayer are not ‘My Father’ but ‘Our Father’, and ‘we’ and ‘us’ continue all the way through: there is no ‘I’. Only God is singular. However we do it – whether we kneel, sit, stand or prostrate ourselves– it is ‘we’ who pray. As in almost all religious rituals, to connect with God is also to join more fully with each other.

Yet at the same time as binding communities together, the public call to private prayer can also drive them apart. The Angelus in France in the late nineteenth century, as in modern Ireland, came to be seen as a symbol of a national identity which was consciously – and, to many, controversially – Catholic. In central Europe today, strident arguments about European cultural identity have crystallized around the competing sounds of the traditional church bell and the muezzin’s call to prayer, which some feel proclaims Islam in an intrusive and unacceptably public way. The underlying question: is Europe an essentially Christian civilization, or not? In Germany, the Pegida movement protests against the Islamization of the West; in France, Islamic prayer in the street is forbidden (Chapter 28); and in 2009 in Switzerland, a majority voted in a federal referendum to ban the construction of all new minarets. But it is not only historically Christian lands which seek to defend their traditional identities. Saudi Arabia, for example, does not allow the building of Christian churches, even less the ringing of church bells or praying in public. Prayer, the most intimate spiritual activity, can when practised communally be an explosive political topic.

The controversial construction of minarets such as this one in Wangen, Switzerland, led to a federal referendum in 2009.