26

THE MANDATE OF HEAVEN

Queen Elizabeth II after her coronation in 1953, holding the orb and sceptre, photographed by Cecil Beaton

And as Solomon was anointed king

by Zadok the priest and Nathan the prophet,

so be thou anointed, blessed, and consecrated Queen

over the Peoples, whom the Lord thy God

hath given thee to rule and govern,

in the name of the Father, and of the Son, and of the Holy Ghost. Amen

Westminster Abbey, 2 June 1953. The Archbishop of Canterbury pours holy oil over Elizabeth II during her coronation. Like the biblical kings of Israel, but unique now among European monarchs, she is the Anointed of the Lord. Nobody watching that ceremony could fail to be moved by the idea of the sovereign, wearing a simple tunic, being invested with all temporal power by the Almighty, and anointed in his name. The choir sings Handel’s ‘Zadok the Priest’, as at every coronation since George II’s in 1727, for which the anthem was composed. The archbishop invokes Solomon, wisest of all monarchs, but he also mentions Nathan – the Hebrew prophet who, in the Book of Samuel, rebuked and publicly humiliated Solomon’s father, the great King David, and called him to repentance for abusing his power. To be a leader in the eyes of a people, it has in most societies, and for most of history, been necessary to be their leader in the eyes of God. Divine endorsement has usually been central to the idea of monarchy, but divine right comes with a no less divinely sanctioned duty to your people: authority is matched with a penalty for breach of trust. As Nathan reminded David, a king – or queen – must make, and must keep, an oath made before God.

The defining image of the Queen’s coronation is of the young monarch, fresh from taking her oath, sitting beneath the weight of her new crown and holding the orb and sceptre – the symbols of power spiritual and temporal. Both are kept with the Crown Jewels in the Tower of London. But in the British Museum you can find these two forms of sovereignty combined in one single sceptre – or, more accurately, staff of office. Around a metre long, cast in brass and about 200 years old, the staff swells at three key points along its length to form figures representing separate dimensions of the sovereign’s authority. Each figure is decorated with intricate patterns, the brass expertly cast to suggest a wide variety of textures. Together, the three figures show what it means to be a divinely ordained monarch in Africa. At the top is the king, holding a leopard in either hand, and with a pair of mudfish that issue from his nostrils. Below his feet is a frog, set between two small severed human heads. The king we see here is a stylized likeness of the Oba of Benin, ruler of a mighty kingdom in what is today southern Nigeria and which had its capital in Edo, now Benin City, about 300 miles east of Lagos. At its height in the sixteenth century, Benin controlled a large, rich and tightly organized empire, and it remained a significant power until the early twentieth.

Osaren Ogbomo, a brass-caster from Benin City, explains the significance of the different figures shown on the staff:

All this symbolizes the weight of the land (the leopards) and the sea (the fish). The Oba is in charge of all these things, because we believe that the Oba of Benin is the earthly god. Every Benin man or Benin woman knows that the Oba is a representative of god on earth.

The brass staff of office of the Oba of Benin, showing him as ruler of all, and lord of life and death. Eighteenth or nineteenth century

The figure in the centre of the staff, a little below the Oba, is disconcerting: it is a man without a torso – a human head with arms protruding from his scalp, and legs from his jowls.

In Benin, in my language we call him ‘Ofoe nuku Ogiuwu’, the messenger of death. When you are against the Oba, if you are against his laws, Ofoe nuku Ogiuwu will visit you. To go against the laws of the land is to play with your life.

The third figure, towards the base of the staff, is a head modelled with full lips, which are pursed as though about to speak; and this figure too has mudfish emanating from its nostrils:

This is the chief priest of the Osun shrine, dedicated to a deity that helps the Oba in controlling the entire community. All the deities have their own priest. And each priest receives his power from the Oba.

We have no written records from Benin itself that tell us exactly what the Oba did with this staff, but we do know from European visitors’ accounts that he was, just as it shows, both a religious and a political leader. Portuguese travellers in the mid-sixteenth century, for example, reported that the Oba would never eat in public, because his subjects believed him to be a god, and so he could survive without food. It was crucial to his authority to maintain that belief.

The Oba’s authority was extensive, running across trade and tribute, tax and justice. In so far as we can reconstruct the role without written sources, the Oba seems to have begun essentially as a warrior-leader, becoming in later centuries a more secluded performer of religious rites, the guarantor of the safe and prosperous interaction of the human and spiritual worlds. In the later nineteenth century European traders and colonizers – above all the British – encroached ever more aggressively upon Benin territory. Finally, in 1897, there was a bloody showdown. A British delegation was attacked on its way to Benin City, and in retaliation London ordered a ‘punitive expedition’. The territory was occupied, and much of Benin City destroyed. The British army carried away great quantities of art, including many exquisitely worked brass sculptures, which became widely, if inaccurately, known as the Benin bronzes. These were mostly sold off at auction and are now dispersed in museums around the world. Before 1897 export of brass objects had been forbidden – which is why the sculptures seized and sold by the British troops attracted great attention from scholars when they reached the outside world.

The kingdom of Benin was incorporated into what became a British colony, and later the republic of Nigeria. But the office of Oba survives to this day, and he still plays a significant role in the ritual and spiritual life of his people.

As the animals on this staff of office imply, the fusion of the natural and the supernatural in the person of the Oba is a central aspect of his kingship. He is thought to understand better than anybody else the deities and forces that govern the world and to be able to channel them in order to protect the community from harm. One purpose of the Oba’s staff is to assert those claims in a public context, symbolically linking the ruler to animals with particular significance. Mudfish, for example, can live for a long time on land as well as in water, so they suggest that the Oba also can move between elements, with power over land and sea.

The Oba of Benin with fish and leopards, spiritually in control of land and sea. This sixteenth-/seventeenth-century plaque, used to decorate his palace, was taken by the British army in the raid of 1897.

In each hand the Oba holds a leopard. Dr Charles Gore of the School of Oriental and African Studies in London explains:

The leopard of the bush is the most powerful animal in the forest and can kill any other animal. Likewise, the Oba of Benin is the political and spiritual head of the kingdom, and he is the one person who has the right of life and death over his subjects. Humans cannot oppose the king because he is not human in the way that his subjects are. He is part of the natural world.

Then there are the two severed heads and a frog. Prior to 1897, an important part of activating metaphysical energies in the world was the sacrifice of animals, in certain circumstances humans. The fact that human heads are being sacrificed represents the capacity and power of the king, rearticulating the idea that the king alone has the right of life and death over his communities.

The very material of the staff is in itself a statement of royal power. Charles Gore continues:

Leaded brass, bronze, ivory and coral don’t disintegrate in a tropical climate, which for 90 per cent of the year is very humid and is home to insects that will eat and destroy a piece of wood within only a few years. The use of these materials is making an iconic statement about kingship: that it’s permanent. It will last as long as these materials last. Any visitor to the Oba’s palace would be dazzled by an array of objects made from materials that are resistant to change, that endure.

The monarchy of Benin has indeed, like brass, endured. On 20 October 2016 the coronation of the current Oba drew huge and enthusiastic crowds. He no longer has the power of life and death, and most of his subjects are now Christian or Muslim, but the Oba, ritually initiated into his ancient office, is still profoundly revered as the father of his people.

The Oba’s staff was designed to assert the absolute authority inherent in him from his divine nature: he ruled as a god and with the gods, because he was in some sense one of them. There is another grand metal object in the British Museum which offers a radically different view of the terms on which a ruler holds office under heaven – one that insists that royal authority is not absolute, but is exercised subject to stringent conditions, and is very much dependent on performance.

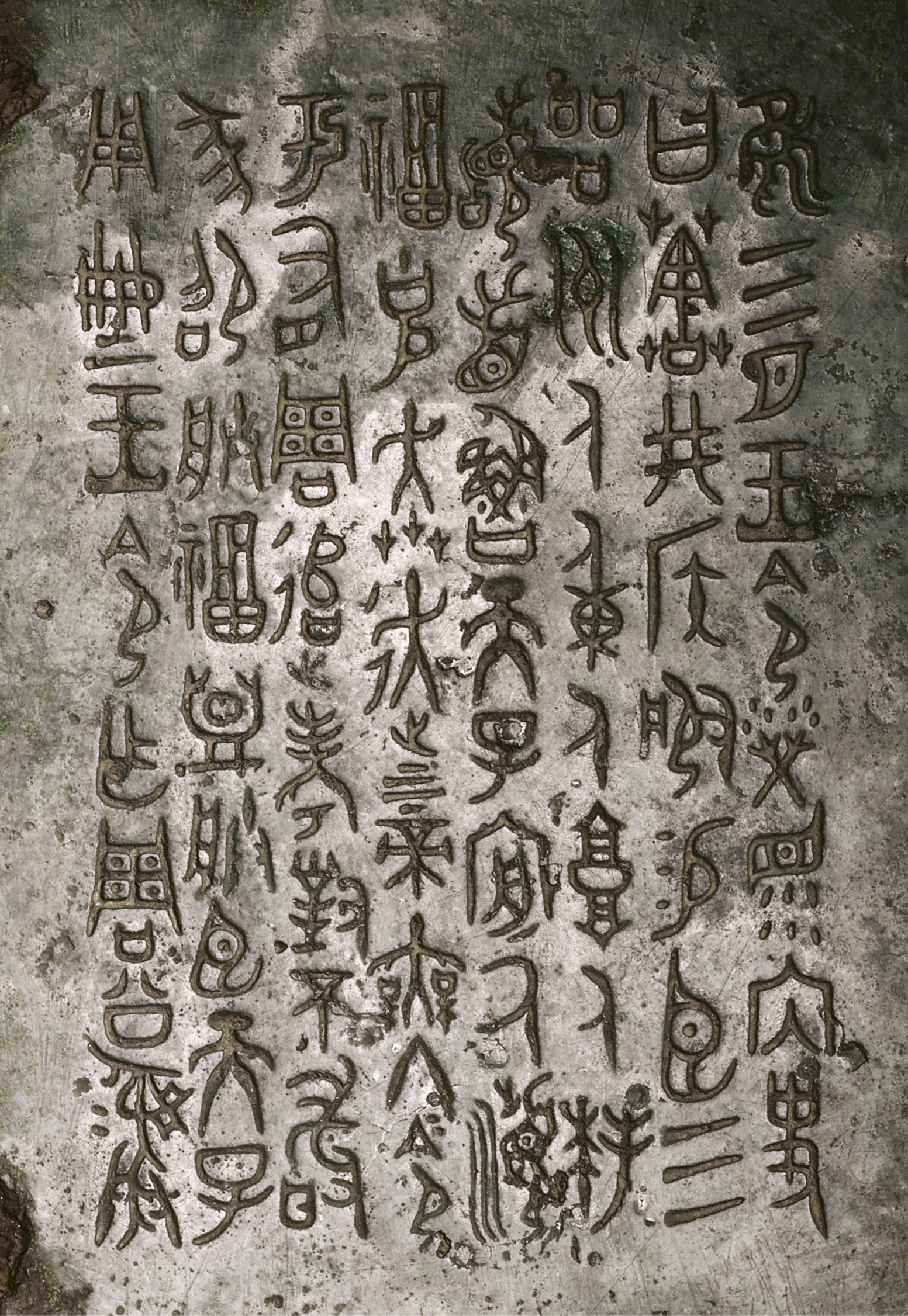

Made in China between 1000 and 800 BCE, this magnificent gui, a round-bodied cooking pot about forty centimetres across, is cast in bronze. It would probably have been used to prepare ritual meals for the dead – an important part of Chinese ceremonies designed to honour the ancestors (Chapter 6). It has four large handles, which divide the outside of the pot into separate sections. On each of these, cast in low relief, is a fabulous creature, a schematized, playful, geometric elephant, with just a hint of dragon in it. These are superb feats of technical metalwork that at this date could have been made nowhere in the world but China.

But for our purposes it is the inside of this beautifully crafted vessel that matters most; for there we find an inscription that records a marquess being granted certain rights by a king of the relatively new Zhou dynasty. After talking of the ritual observances due to the ancestors, it notes the unimpeachable source of the king’s authority – he is described as the son of heaven. At first sight, this seems very close to the divine endorsement enjoyed by both Elizabeth II and the Oba of Benin. But there follows what is to Europeans an unexpected thought:

We cross our hands and lower our heads to praise the son of heaven for effecting this favour and blessing. May the High Ancestor not end the mandate for the existence of the Zhou.

A ceremonial bronze pot cast in China between 1000 and 800 BCE.

This gui is the earliest evidence we have of a concept of leadership that has held sway in China for 3,000 years. The Zhou dynasty had overthrown their rivals and come to power around 1050 BCE. They had been able to do so, they claimed, not just because they had, like so many new Chinese rulers, conquered in battle, but because they had what came to be called a Mandate of Heaven. And, strikingly, in our pot, they feel the need to pray that this mandate will not be taken from them.

For Yuri Pines, Professor of Asian Studies at the Hebrew University of Jerusalem, this is a very unusual view of a monarch’s divine right:

The right to govern can be removed. If our descendants mis-behave, inscriptions like this are saying, if they oppress the people or fail to maintain a good political system, then heaven will replace us and give the mandate to somebody else. This is the real novelty: the Zhou are saying that heaven’s grace cannot be taken for granted.

Inside is an inscription describing the king as the son of heaven, ruling by – revocable – divine mandate.

European Christian monarchs, ruling ‘by the grace of God’, understood their authority as rulers to come from the same God whom their people worshipped. The Chinese Mandate of Heaven was very different:

In China, the religion which sanctifies the role of the son of heaven (the emperor) is not a popular religion, the religion of the masses, but rather the private religion of the emperor and his immediate entourage. There are no priests who claim to speak on behalf of heaven. There is no such collision of the sort that we find in Abrahamic religions, where prophets (like Nathan) tell kings: ‘Sorry, God has told me that you’re wrong.’ Instead, in China, heaven usually manifests its will either through omens and potions, which are then interpreted, or through popular rebellion or discontent.

This particularly Chinese notion of divine right, inscribed on the inside of our gui, attached great significance to such popular manifestations. It did not mean that every uprising would be sympathetically listened to. But there were scholars at the imperial court whose job it was to know the will of the people – and through them the will of heaven. If enough people expressed sufficient discontent over a lengthy period of time, the scholars might suggest that the ruler’s time was up, that heaven had turned away in displeasure – or, to use the words of the inscription tucked away inside the gui, that the High Ancestor had brought the Mandate to an end.

One might expect that an idea like the Mandate of Heaven would be anathema to the atheist principles of China’s Communist regime. But not so. The Mandate has always been as much a political philosophy as a religious ideal: it recognizes that a restive population will in the end be able to topple even those whose power appears unassailable.

According to Yuri Pines, this is an idea that Communist teaching has failed to dislodge, and which perhaps lies behind Western misunderstandings of contemporary China, and of the differences between Russian and Chinese communism:

The idea that popular discontent indicates a lack of legitimacy of the government remains very powerful. If the people are strongly dissatisfied, then the government must reflect on it and somehow modify its ways. The consequence of this way of thinking is a system that is much more flexible and attentive to the people’s opinion than we would normally expect with authoritarian political systems.

The idea of the Mandate of Heaven may actually be more important now than in the past, because theoretically the Communist Party is the party of the people. To put it mildly, elections in China are not very significant. But the people’s level of satisfaction with the government is. In China, people don’t have any real possibility of voting you out, but they have a much more potent weapon: if they rebel, it will mean disaster for the entire political system. So it is much better that you pay attention every day to what the people want, thinking all the time that the Mandate of Heaven is not for ever – even though, of course, officially now nobody uses this term.

Mao’s successors saw that some of the most destructive aspects of his rule – the famines of the Great Leap Forward, or the chaotic violence of the Cultural Revolution – had brought the country to the brink of yet another uprising. So, on this reading, in the decades following Mao’s death they stepped back and took a radically different direction, thus preserving not just their power but their Mandate to rule.

In Britain today the Queen’s anointing and the sacramental dimension of her constitutional role are often forgotten. But in Russia and the United States the Christian God now plays a conspicuous part in politics. Both Vladimir Putin and Donald Trump offer themselves to their people as strongmen enjoying the favour of divine power. Putin’s supremacy has gone hand in hand with the revival of the Russian Orthodox church, which co-operates with his regime, and of which he is an ostentatious supporter (p. 453). President Trump’s inauguration in 2017 was almost a religious festival, with church choirs and multi-religious prayer. ‘There should be no fear,’ the new American president told the nation. ‘We are protected and we will always be protected…by the great men and women of our military and law enforcement. And, most importantly, we will be protected by God.’