28

TURNING THE SCREW

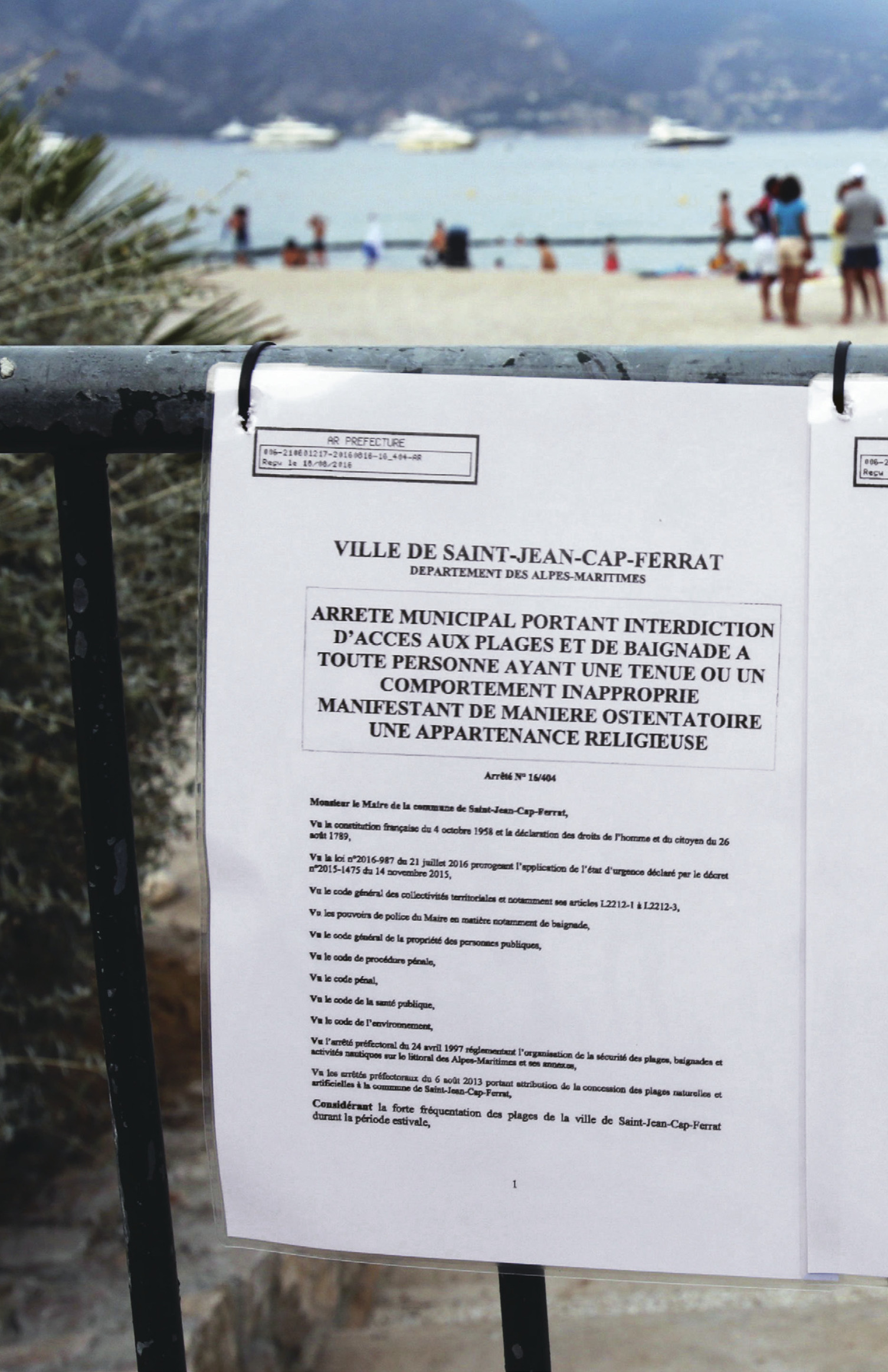

Banned from the beach: the municipal authorities forbid on the beach any behaviour or clothing which demonstrates religious allegiance, French Riviera, 2016.

For over a hundred years, fashionable sun lovers have flocked to the beaches of the French Riviera. Over those hundred years bathing costumes have become steadily skimpier, sometimes disappearing altogether, to the delight – or disapproval – of others on the beach. Every now and then, though ever less frequently, the police have intervened, declaring that ‘Un outrage aux bonnes moeurs’, an affront to decency, has occurred. But if, in the summer of 2016, you had risked wearing a particular kind of swimsuit on a number of Riviera beaches, including Cannes, St-Jean-Cap-Ferrat or Villeneuve-Loubet, you might well have found the state stepping in to stop you – police warning you against the disrespect you were showing not just towards the ‘bonnes moeurs’ of proper behaviour, but also towards laïcité – the principle of secularism enshrined in the French constitution since the early twentieth century.

All this, not because you were wearing too little – because you were wearing too much. The bathing costumes causing the fuss were burkinis – full-body swimsuits, intended for women who want to observe Islamic modesty codes while on the beach or in the sea. They were originally designed in Australia, but rapidly became popular among Islamic women in Europe. In most countries, they attracted little attention. But in August 2016, when France was struggling to come to terms with several terrorist attacks, a number of towns on the Côte d’Azur invoked the law to prevent women – they were of course all Muslim women – from wearing them on local beaches. It quickly became much more than a local issue: French national politicians queued up to support the restriction and to insist that, beyond the bathing costume, a fundamental constitutional principle was at stake. Wearing the burkini, it was declared, was not compatible with French values. In the words of the then Prime Minister: ‘The burkini is not a fashion – it is the expression of a political project, a counter-society.’

The rest of Europe was bewildered. How could wearing a supremely modest swimsuit, designed in Australia, be seriously considered a step towards a ‘counter-society’, or cause such a constitutional storm? The answer, of course, is that – as the Prime Minister said – it had little to do with clothes, and really was about politics; more specifically, it was about the collision of politics with faith. The point at issue was the public demonstration of religious allegiance in a French state which has for over a hundred years defined itself as exclusively and uniformly secular.

Behind that, however, lies another more general question: how do states with a clear view of what constitutes national identity accommodate – or oppress – a minority faith seeking publicly to assert its distinctiveness? To look at that question, I want to start not on the beaches of the French Riviera in 2016, but in seventeenth-century Japan.

Christianity has been forbidden for many years.

If you see someone suspicious, you must report them.

Rewards will be given as follows:

For handing over a priest – 500 pieces of silver

For handing over a monk – 300 pieces of silver

For someone who has returned to their Christian faith – 100 pieces of silver

For reporting someone who shelters Christians, or is an ordinary believer, you may be paid up to 500 pieces of silver, depending on their importance

The Magistrate, 1st day, 5th month, Tenna 2.

It is hereby ordered and must be strictly observed in this territory.

These chilling words, written in Japanese, are painted in black ink on a crudely made wooden noticeboard, almost a metre wide, with a little gabled ‘roof’ to protect the writing from the rain. The era of ‘Tenna’, or Heavenly Imperial Peace, began in Japan in September 1681, so this inscription dates from early 1682. As Tim Clark, Head of the Japanese section at the British Museum, explains:

It is a typical public noticeboard of the period, called a kusatsu in Japanese, and it is part of a system that had been used by the central government – or Shogunate – since the early seventeenth century to enforce its regulations throughout the whole country. There were hundreds of such noticeboards all over Japan, typically located at the approaches to bridges and along public highways, where large numbers would see them – rather like hoardings beside a modern motorway. They carry prohibitions against behaviour deemed to be a threat to the state, such as counterfeiting currency, peddling fake medicines or poisons, and so on – or, as here, against sheltering anyone connected to Christianity.

Japanese noticeboard offering substantial rewards to anybody denouncing or turning in Christians, 1682

What was it about Christians that led the Japanese state to see them as a dangerous ‘counter-society’, a threat to the state that could properly be condemned alongside poisons and counterfeit currency?

By 1600, Japan was home to a surprisingly large number of Christians: around 300,000, out of a total population estimated to be 12 million, the great majority of whom practised a particularly Japanese mixture of Buddhism and traditional Shintoism (Chapter 18). The increasing number of Christians worried the state authorities, but the ‘threat’ from Christianity went much deeper.

Christianity had entered Japan in 1543 with a group of Jesuit missionaries led by Francis Xavier, travelling on Portuguese trading ships carrying all kinds of European goods, not least guns. The Portuguese merchant venturers and Christian missionaries arrived at a critical time in Japanese history, when the country was in the grip of civil war, split between rival regional rulers. Tim Clark describes how eventually, towards the end of the century, Japan was once again united under a strong central government. Portuguese rifles, and Japanese copies of them, had played a significant part in making that happen:

Nagasaki, the main port in south-west Japan, became the centre of Portuguese trade, in guns and much else, and also of Catholic missionary activity. In due course the entire city was effectively ceded to the Jesuits. Many rulers in the area converted to Christianity, sometimes for their own personal pious reasons, sometimes with an eye to the profits of trading with the Portuguese. They would normally then ensure that all their subjects also became Christian, through mass baptisms, with tens of thousands of people converting at the same time. For the newly established central government, still uncertain of its authority, these territories, controlled by prosperous Christian convert rulers, came to be seen as an alternative, and very dangerous, power base, a threat which simply could not be tolerated.

On a Japanese seventeenth-century folding screen, a Portuguese trade ship arrives in Nagasaki, carrying European goods and Jesuit missionaries. After unloading, the Europeans are taken to kneel before the local ruler (top right).

By the end of the 1500s the Jesuits based in Nagasaki had also become a force to be reckoned with. They were setting up schools and preaching persuasively to the powerful. Disturbingly, they clearly looked for ultimate authority not to any person or system inside Japan, but across water and land all the way to Rome – and from there to a God apparently hostile to the traditional deities of Japanese Buddhism and Shinto. This alien allegiance had dramatic local consequences, especially in the region around Nagasaki. One prominent Christian ruler, for example, Ômura Sumitada, who took the name Dom Bartolomeu on his conversion in 1563, a few years later ordered the destruction of all the Buddhist temples and Shinto shrines within the area over which he held sway.

Two years later, in 1565, a large group of islands south-west of Japan was invaded and claimed in the name of the Spanish king. The fate of the ‘Philippines’ seemed to offer the Japanese a disturbing warning, says Tim Clark: the Christian Bible is likely to be followed by the Spanish sword:

Christianity posed a complex threat to the Japanese leaders, concerned above all to hold the state together. They were working on a knife-edge. Native Japanese religion, initially Shinto (the worship of the traditional kami gods of Japan) and then latterly Buddhist, had by this point been well established in Japan for at least a thousand years, a major unifying force. The two traditions had managed to co-exist by finding equivalent deities in each other’s pantheons, leading to a kind of syncretic belief in both religions at once (see Chapter 18). To the Japanese way of thinking, Christianity was very intransigent. Unsurprisingly to us, but shockingly to the Japanese, it would not accept the Buddhist or the Shinto deities as being equivalents – or avatars – of the Christian god and saints: instead, it declared itself in possession of the only truth. I think ultimately this meant that Christianity was in a philosophical way seen as incompatible with Japanese culture.

The Franciscan Martyrs of Nagasaki. On 5 February 1597, twenty-six Christians were publicly crucified by the Japanese authorities. This engraving by Jacques Callot, 1627, shows only the twenty-three Franciscans: the Jesuits are not included.

Soon enough, these twin worries, about aggressively intransigent missionaries and the uncertain allegiances of their Japanese Christian converts, combined to inspire acts of repressive violence. Hideyoshi, the general who in 1590 had effectively made himself supreme in a unified Japan, crushed local opposition, banished Christian missionaries from his territories, and described Japan as ‘the land of the gods’, meaning the ‘national’ gods of the Shinto and Buddhist tradition.

In 1597 twenty-six Christians were put to death in Nagasaki, all crucified, in a macabre and brilliantly stage-managed public spectacle, whose attention to detail included piercing their sides with spears. The massacre was widely publicized in Europe, where Jesuits and Franciscans were engaged in bitter conflict with the Protestants, and proudly proclaimed the courage and faith of Catholic martyrs on the far side of the world.

Thereafter, the pace of prosecution quickened. In 1614 Christianity was officially prohibited in Japan. Churches were demolished or converted into temples. In 1639 the Portuguese – and with them the Catholic clergy they protected – were expelled. The exclusive right to trade with Europe was given instead to the Protestant Dutch, who were delighted to see Catholic Spaniards and Portuguese discomfited, and were happy to trade (extremely profitably) without meddling in matters religious. Nagasaki became Japan’s only point of contact with the world beyond Asia. All other ports were closed to foreign ships.

The Catholic priests had gone. The church, as a church, no longer existed. But to ensure the complete eradication of the alien faith, the state went even further. Anybody suspected of being a secret Christian was obliged – on pain of death – to appear in a nearby Buddhist temple. There, in order to demonstrate that they were no longer part of the forbidden sect, they had publicly to abjure their faith, and stamp on a small plaque carrying the sculpted image of Christ or the Virgin Mary. Some of these fumi-e, literally ‘stamp-images’, have survived. They are, I think, inexpressibly poignant. In the history of art, they form an almost unique category: images of real quality made explicitly to be humiliated and destroyed. Based on Flemish or Italian engravings, frequently sculpted by Japanese artists, they show scenes of Christ’s life and Passion, still just legible, but almost worn away by the feet of those forced to desecrate them: faint remains of a faith wiped out.

Left: Stamping out the foreign faith: painting on silk showing the annual fumi-e loyalty test. Nagasaki, Japan, 1820s. Right: Bronze fumi-e with an image of the Crucifixion, worn away by those who trod on it to prove they had renounced Christianity

This systematic persecution was, not surprisingly, extremely effective. By the 1660s there were virtually no publicly practising Christians left in the main part of Japan; and those who continued to pray in secret hardly posed even a notional threat. So when in 1682 the state issued the edicts painted on our noticeboard, they were aiming at a foe already long vanquished. Why? Tim Clark explains:

Christianity remained a useful symbolic enemy, a hypothetical danger which the central government could deploy to its advantage as an instrument of social control. Even though there were in effect no Christians left in the country, it was important for the authorities to insist that they had to inspect all books coming into Japan, so that they could excise any references or imagery associated with the Christian faith. This justified a censorship system and a tight grip on all overseas contacts, which served very well to keep control over many other aspects of society.

So the creation and posting of boards like this was not really about banning something – it was about demonstrating the power to ban something. These edict-boards doubled as propaganda for a new, centralized Japanese state and its rulers. You now live in a country – says this board – that possesses the legitimacy and the manpower to banish foreigners from its shores. It is in a position to keep a very close eye on you and everything you do.

This, in other words, was a state not so much protecting itself against outside threat, as asserting its control over its own people by doubling down on the already defeated. This was now the natural order, social, spiritual and political. To be Japanese was to live in the land of the traditional gods, and there was no room in it for a deviant sect like Christianity, which originated from abroad.

The edicts stayed in force and were regularly reissued for nearly 200 years, and the assumptions behind them have continued to influence Japanese habits of thought down to the present. People were still being punished, and indeed executed, for being Christian when Commander Matthew Perry arrived in the Bay of Tokyo in a US warship in 1853 and forced, this time with American guns, the opening of Japanese ports, and minds, to the world.

In the 1690s, a few years after the edicts urging the Japanese to denounce fellow citizens whom they suspected of still being Christian, Sébastien Leclerc, the most celebrated engraver of his day in Paris, began work on a print of the Destruction of the Huguenot Temple (or church) at Charenton, a few miles east of Paris. The church, erected in the 1620s, was the work of Salomon de Brosse, architect of the Luxembourg Palace in Paris. It was the most prominent Protestant church in France, renowned across Europe for its generous congregational space, perfectly shaped for preaching. It had been widely admired by Jewish and Protestant architects, and among other buildings had inspired two great synagogues in Amsterdam and Christopher Wren’s church of St James’s, Piccadilly, in London. In October 1685, on the orders of Louis XIV, de Brosse’s sober masterpiece was razed to the ground.

Leclerc’s engraving is a disturbing work of art. He animates and agitates his composition with abrupt shifts from bright, blank white to heavily hatched darkness. The ordered classical columns and galleries on the left are reduced to a dense heap of rubble in the centre. Large numbers of workmen hack and haul with brio: walls are demolished, beams brought down, and columns and window frames carried off as spoil. The detail of this work of boisterous destruction is eerily legible – frenzy recorded with precision. At bottom left a soldier holding a halberd calmly monitors progress, while, on the right, two figures in silhouette point to a brightening sky. With consummate mastery a great engraver celebrates the destruction of a great piece of architecture.

One of the King’s Little Conquests: Sébastien Leclerc’s engraving of the destruction of the Protestant church at Charenton after the Revocation of the Edict of Nantes in 1685

Like the Japanese noticeboard, this engraving is part of a series. It is one of Leclerc’s Petites Conquêtes du Roi, the ‘Little Conquests of the King’, a series of eight engravings produced around 1690 to celebrate the achievements of Louis XIV. As you might expect, there is also a larger-format series called Les Grandes Conquêtes du Roi, showing the king’s many victories over the enemies of France. The years around 1690 were the military and diplomatic high point of Louis XIV’s reign, the culmination of twenty-five years of almost constant aggressive warfare against the Habsburgs and their allies. For the first time in over a century, France was now secure against attack, and militarily supreme in Europe. These two magnificent series of prints are effectively state propaganda – we know that Leclerc was paid by the royal household while producing the Grandes Conquêtes. Every image is clearly labelled to identify the event being celebrated, and framed with abundant allegorical detail reflecting on the action. Leclerc’s engravings allow the viewer fortunate enough to own them (they were expensive collectors’ items) to look with informed wonder and visual delight at the feats of the self-styled Sun King.

Six of the Petites Conquêtes are what you would expect: scenes of battles, mostly against Austrians, Spaniards and Dutch, on the northern and eastern frontiers of France. But two celebrate other kinds of victories. One is the reception at Versailles in 1686 of the ambassadors of Siam, a great diplomatic coup, which opened a new avenue for French foreign policy in the Far East. The other is the demolition of the temple at Charenton, a ‘victory’ a few miles from the capital, this time over the king’s own loyal Protestant subjects.

The religious Reformations of the sixteenth century had transformed Western and Central Europe from a region of broadly uniform belief and practice into one of shifting and competing denominations. And that led to a profound, indeed existential political question: could any European state, for centuries structured and sustained by shared Catholic religious practice, continue to function when people within it believed radically different things and could no longer worship together? Could a house divided against itself stand? In France that tension led to a generation of civil war between Roman Catholics and Calvinist Protestants, which by the 1590s had cost countless lives and devastated the country. France had to find an answer. That answer finally came when Henry IV issued the Edict of Nantes in 1598.

France’s Protestants – the Huguenots – were allowed to practise their faith, subject to many restrictions, and were given guarantees to protect their rights. The Edict of Nantes brought peace, and with it a stability that allowed the French crown to start rebuilding the state. In a process strikingly similar to Japan’s, the bloody civil wars of the sixteenth century were followed in the seventeenth by the establishment of an ever more authoritarian centralized power, insistently claiming to defend the traditional faith. And, in both countries, in the 1680s that power was asserted against a small and weak religious minority.

The Edict of Nantes was toleration of a sort, but it left Huguenots essentially with the status of unwelcome guests – or guests who would, if one waited long enough, eventually come round to the right way of thinking and return to the Catholic fold. By the early 1680s Louis XIV was prepared to wait no longer. He showed the Huguenots what it was like to have unwelcome guests, by billeting his troops in their homes. The soldiers terrorized and impoverished the Huguenot families and wrecked their houses. The only way to avoid ruin was to convert to Catholicism. It was the culmination of a long campaign of harassment over decades. The civil rights of Huguenots had been steadily eroded, professions closed to them and pensions withheld. Large numbers abandoned their faith or emigrated.

In consequence, the Protestants had effectively been broken as any kind of coherent force by the time that Louis took the final step on 22 October 1685 and revoked the Edict altogether. By that act, the practice of the Protestant faith was declared illegal, all Huguenot civil rights were withdrawn, their clergy were to be subject to the death penalty, and their churches demolished. The destruction of the Charenton temple began the next day. The Revocation of the Edict of Nantes was one of the most popular decisions of Louis’s long reign.

Professor Robert Tombs of the University of Cambridge thinks this explains the number of people to be seen at work in Leclerc’s engraving:

It is as if this is in a sense not an act of the state, but an act of the people, who have been permitted by the king’s revocation of the decree to vent their hatred of Protestantism. There was widespread popular participation in wrecking Huguenot churches, and in desecrating Protestant cemeteries: the king in this sense was giving free rein to the sectarianism within the kingdom, an absolute monarch playing the populist card.

If this reading is right, there is a disturbing echo here of the destruction of the mosque at Ayodhya (Chapter 25), where the state also appears to have stepped aside and left the people to carry out the work of destruction. And as in India, says Robert Tombs, the French decision was made with an eye to international politics.

Louis is claiming to be the Rex Christianissimus, ‘le roi très chrétien’, the title always assumed by the French monarchy to demonstrate that it – and France – were, in another famous phrase, the ‘eldest daughter of the church’: it was an assertion that Catholicism was the hallmark of the French monarchy, the basis of its claim not only to legitimacy at home, but to primacy in Europe. In 1685 Louis was particularly eager to repeat that claim, as he had been widely criticized for allying France with the Muslim Turks against the Habsburgs, and was on exceedingly bad terms with the Papacy.

The final suppression of Protestantism was intended to substantiate the claim that the French monarchy was, in spite of supporting the Turks and opposing the political interests of the Pope, the faithful ‘eldest daughter’ of the church of Rome. Which explains why, presiding over the print’s frame, is the allegorical figure of the ‘Catholic Church Triumphant’, adorned with crosses, incense-burners and the papal tiara. On either side books, presumably heretical Protestant books, are burning. From the bottom of the frame hang chains of the sort used to shackle prisoners condemned, as many Huguenots were, to serve in the royal galleys. The viewer can be in no doubt that the king of France, in persecuting the Protestants, is doing the work of God’s holy church.

Louis XIV triumphing over heresy, 1685 – the year of the Revocation of the Edict of Nantes

And yet the Huguenots to the end insisted that they were the most loyal of Louis’s subjects, firm believers in the king’s divine right to make what decisions he thought proper. Like the Christians in Japan at the same date, they were in no way a threat to an ever more assertive central state. So why, other than to cut a Catholic dash in front of a disaffected Papacy and a sceptical Europe, did Louis regard their crushing as a conquest to be celebrated? Robert Tombs sees here the beginning of a pattern of political thought which is still very much alive:

The Edict of Nantes had given Protestants considerable political and military rights, and I think, without being too fanciful, that one can see in the Revocation the origins of the strong, and now very long-lived, French dislike of anything that might be seen as a state within the state. That was the charge against the Protestants under Louis XIV. It was said to be true of them still in the nineteenth century; and later said to be true of Jews, a debate that shaped much of the argument about national identity around 1900; and today of course, in remarkably similar terms, it is said about Muslims.

There was a very interesting debate in the National Assembly in 1789, discussing the status of Jews in France. A famous speech laid down that one should give everything to the Jews as individuals, but give nothing to the Jews as a community. The idea is that a religion, let us say Islam today, is to be seen not as a number of individuals who hold a particular set of beliefs, but as an organized group who claim some sort of separate identity.

If one doesn’t believe too readily in historical coincidences, then one would think that there must be some continuity of attitude here, a certain way of understanding what it means to be French.

Leclerc’s engraving should no longer surprise. Seen in this light, the challenge posed by the mere existence of the Huguenots to this new unitary notion of Frenchness was as dangerous and insidious as any external military threat. And now, thanks to the king, it had been removed: cause for celebration. From this point on, France was to be defined not by blood or language, but by uniform acceptance of its rules and norms. It is, Tombs suggests, the startling strength and longevity of this political attitude which explains the intensity of French reaction to the burkini on the beach with which this chapter began:

The revolution of 1789 tries to create a new kind of unity, based not on the uniformity of Catholicism but on a uniformity of secularism which later came to be called laïcité. It insists that religious belief and practice have no role in the public life of the state. They should remain a private matter, in which case no one will be troubled. But when people start to display their religious beliefs in public, and start claiming for their religious status something that marks them off from other citizens, then neither republicanism nor traditional French royalism can accept it.

For Republicans, who are at the forefront of the moves to ban the burka and the burkini, it goes much further. Secularism is seen by hardline Republicans as a fundamental part of what it means to be French. Without secularism, many would say, there cannot be true equality between men and women, there cannot be true democracy.

If we follow this line of argument, the existence of the temple at Charenton, like the wearing of the burka or the burkini, is to the authorities a provocative refusal to accept what it means to be a true citizen of France. They may in consequence take ‘appropriate measures’.

Christianity never really recovered from its persecution at the hands of the state in seventeenth-century Japan. When the regime was overthrown in the middle of the nineteenth century, Japan’s new leaders restored to the centre of national life an emperor declared to be divine (Chapter 4). Jealously protective of this most potent of symbols, these leaders understandably continued the ban on Christianity, until after Commodore Perry’s show of force richer and better-armed Christian states forced them to drop it. ‘There is no room in Japan,’ one Japanese official had proudly declared, ‘for two sons of God.’ Although returning missionaries had found small groups of Japanese still using rosaries, Christianity continued to be regarded as a foreign and therefore suspect faith. The sense of a Japanese identity long preserved by restricting contact with foreigners is thought by many to explain modern Japan’s great reluctance, in spite of a strong economy and a major demographic crisis, to accept foreign immigrants. On the basis of public-opinion polls, it is sometimes joked that most Japanese would prefer to see their aged parents looked after by a robot than by a Filipino.

On 26 August 2016, the Conseil d’Etat in Paris, France’s supreme administrative court, eventually decided that wearing a burkini on a beach did not constitute a threat to public order, and so should not be forbidden. But that other marker of Islamic identity, the full face-covering burka, remains forbidden in the French street. For nearly 350 years, the notion that one can be fully a French citizen, and also visibly a member of a minority religious community – Protestant, Jewish or Muslim – has been thought to threaten the identity of the French state.