AT THE VERY edge of Little Spring Valley, on the other side of town from the elementary school, began a lane that wound far out into the countryside. Near the beginning of that lane, where the air smelled more like country than town but where neighbors could still see the houses on either side of them if they looked hard enough, was a rambling old home belonging to the Clavicles. It was the sort of country house with a wide porch, where the Clavicle aunts hung pots of bright red and pink flowers in the summer. There were gables on the roof, and windows poking out where you wouldn’t expect them, and three staircases inside, and lots of hidey-holes for Almandine Clavicle, who was ten. The Clavicles were a largish family, and even so there were more bedrooms in the house than people to sleep in them.

Almandine liked to make lists, and she pasted them (every single one of them since her very first list, written when she was six) in a book she’d entitled The Collected Lists of Almandine Clavicle. That first list read:

My Pets

1. None

(Some of Almandine’s lists were on the short side.)

A recent list read:

The People in My Family

1. Me, Almandine, 10

2. Mother, 40

3. Father, 41

4. Grandmother (Father’s mother), 72

5. Grandfather (Father’s father), 75

6. Nana (Mother’s mother), 74

7. Auntie Adelaide (Mother’s sister), 45

8. Auntie Columbia (Mother’s brother’s sister-in-law), 48

Almandine had made lists of the furniture in her room, her favorite names for dogs, the types of potatoes she had eaten, the colors of a zebra (1. Black, 2. White), the brands of all the sneakers she had ever worn, and on and on and on.

Mother and Father Clavicle thought Almandine was extraordinary.

“She’s so precise,” said her mother.

“She’s so creative,” said her father, although secretly he wondered about the zebra list.

The Clavicle household was quiet, and Almandine was sweet and obedient. Every day after school she came directly home, ate a snack with her grandparents, and settled down to do her homework. She sat at the desk in her sunny pink-and-yellow room and diligently filled out worksheets and wrote essays. Her report cards were filled with Bs.

“She’s such a wonderfully above-average child,” Auntie Adelaide commented to Auntie Columbia one night.

“And it’s so nice that she always wants to be at home with us,” replied Auntie Columbia. “She’s never even been on a sleepover.”

Almandine had once read a book called Understood Betsy, about a little girl named Betsy (of course) who lives, at least in the beginning of the story, with two older relatives who dote on her and who shelter her from the hardships of life. Then she moves to a farm to stay with different relatives, who expect Betsy to do everything for herself and even give her chores. At the end of the story, Betsy decides she likes these relatives better and wants to live with them. Almandine had been puzzled and didn’t understand the point of the story. “It’s a very strange tale,” she had informed her teacher when she handed in her book report.

Almandine enjoyed her quiet life with all the grown-ups, but every now and then she did wish she had a friend. Sometimes she even dared to wish for a best friend. Most of her classmates had best friends. At the end of every school day, Almandine started off her walk home with six or seven other children who lived nearer to town, but she eventually finished off the walk along the lane all by herself. She would often stand for a few moments in front of the house next door to hers and look at the FOR SALE sign in the yard. The house had once been owned by the Minstrels, a very nice man and woman who were folk singers but who didn’t have any children. They had moved away over a year earlier, and the house was still empty. The FOR SALE sign had become gray and lopsided. Almandine would feel lonely for a few moments, looking at the leaning sign and the empty house, but then she would step through her front door and the grandparents would hug her and give her a snack.

One afternoon Almandine was startled to find Nana waiting for her at the beginning of the lane.

“Is something wrong?” asked Almandine.

Nana smiled at her. “No. I have a surprise for you. Keep your eyes closed.”

Almandine didn’t like walking along the lane with her eyes closed, even if Nana had taken her hand and was leading the way. But she did so—slowly, in case there should be a rock or a snake in her path that Nana didn’t see. At last Nana came to a stop, turned Almandine so that she was facing away from the road (as far as Almandine could tell), and said, “Open your eyes!”

Almandine opened her eyes and squinted in the sunshine. They were standing in front of the Minstrels’ house. She glanced up at her grandmother. “What?”

“Don’t you notice anything? Look around the yard.”

“Oh!” exclaimed Almandine after a moment. “The for-sale sign is gone.”

Nana smiled. “We’re going to have new neighbors.”

After her snack Almandine rushed to her room and began a list:

Things I Hope the New Neighbors Will Have

1. Children, three would be good

2. Dogs, five would be good

3. A trampoline

4. A girl exactly my age

5. Twin girls exactly my age

6. Someone who will be my best friend

Almandine knew this was a lot to hope for, but she couldn’t help herself. She peppered her parents and aunts and grandparents with questions: When will the new people move in? Where are they from? Do they have any children?

Nobody knew the answers.

Every morning Almandine looked out her window first thing to see if a moving van had pulled into the driveway next door. Every afternoon she rushed home from school expecting to see the new neighbors lugging boxes and suitcases out of their car and up the steps of the porch. Finally, finally, after two weeks of waiting, Almandine ran along her lane after school, and there in the Minstrels’ old yard were two cars, a moving van, a man, a woman, three children, and five people wearing BOHREN’S MOVERS jackets. Almandine stopped in her tracks and stared at all the activity. Eventually she noticed that one of the kids, a girl, was looking back at her from the porch.

The girl waved. “Hi!” she called.

“Hi.” Almandine set her backpack down and started across the yard, feeling excited and shy.

“My name is Putney,” said the girl. “Putney Cadwallader.”

“I’m Almandine Clavicle. I live next door.”

“What school do you go to?”

“There’s only one here. Little Spring Valley Elementary. I’m in fifth grade.”

“I’m in fifth grade, too!”

“Maybe we’ll be in the same class,” said Almandine, even though she privately thought this was too much to hope for.

Almandine got busy with her lists that evening:

Things the Cadwuh Cadd New Neighbors Have:

1. Three children

2. A girl exactly my age

3. Two dogs

Things the New Neighbors Do Not Have:

1. Five dogs

2. A trampoline

3. Twin girls exactly my age

Things the New Neighbors Might Have—I’m Not Sure Yet:

1. Someone who will be my best friend

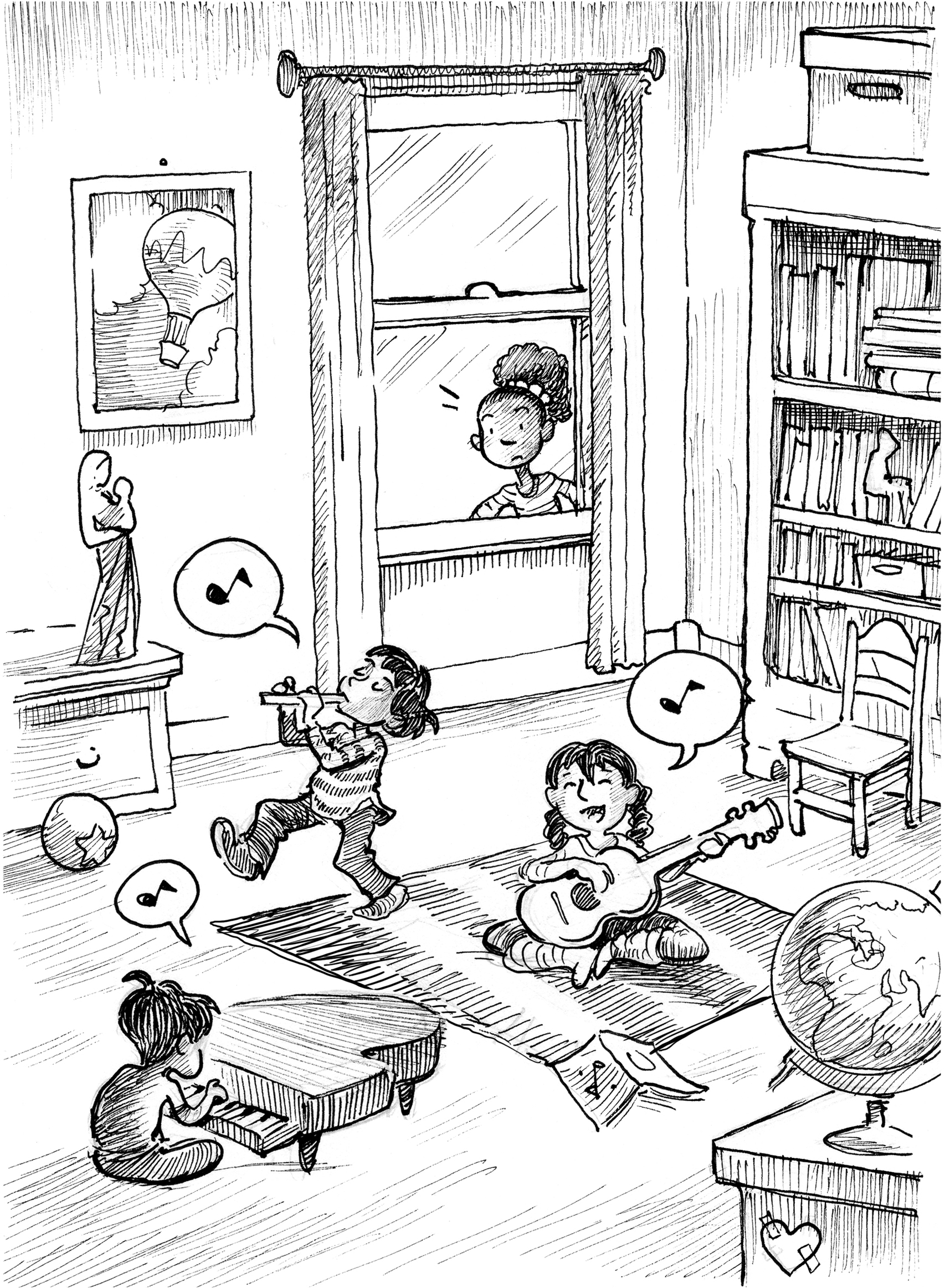

Two mornings later, as the Cadwalladers were settling into their new home and new town, Almandine walked to Little Spring Valley Elementary with all three Cadwallader children—Putney; Joseph, who was eleven; and Benny, who was seven.

“I’m a girl sandwich,” Putney announced. “My brothers are the bread.”

“Do you play an instrument?” Joseph asked Almandine. Before she could answer, he went on. “We all do. Putney plays the guitar, Benny plays the piano, and I play the flute.”

“We’re a trio,” added Benny.

“I don’t play an instrument,” said Almandine, who couldn’t carry a tune and sounded like a cow when she tried to sing.

Benny patted her hand. “That’s okay.”

Two weeks went by before Almandine realized that she did in fact have a best friend, her first best friend ever. She and Putney were in the same class at school. They did their homework together in the afternoons. Sometimes Putney ate dinner at the Clavicles’ house, and sometimes Almandine ate dinner at the Cadwalladers’ house. Almandine and Putney were exactly the same size and could share clothes. They liked to read. They liked dogs. Almandine learned how to spell Putney’s last name.

One night in November, Putney was at the Clavicles’ having her third dinner with them. The Clavicles always ate in the dining room using their good china. They spread cloth napkins in their laps. This was why Putney liked dinner at Almandine’s house. The Cadwalladers ate in their kitchen using paper plates and paper cups to avoid breakage. They used paper towels instead of napkins. Sometimes the dogs drooled under the table. This was why Almandine liked dinner at Putney’s house.

On this particular evening, Grandmother wiped her mouth with a lace-edged flowered napkin and said, “Has anyone heard about the Winter Effluvia?”

“What’s the Winter Effluvia?” asked Putney.

“It’s a particular kind of flu,” replied Auntie Adelaide.

“We only have it here in Little Spring Valley,” added Almandine. “Luckily it doesn’t come around very often.”

“I heard that it’s across town at the funny lady’s house,” said Mr. Clavicle.

“What funny lady?” asked Putney. There was so much about her new town that she didn’t know.

“Missy Piggle-Wiggle,” answered Almandine. “She lives in an upside-down house, only now it’s right-side-up because of the flu.”

“It’s quarantined,” added Nana with a shudder.

“Missy can cure problems,” announced Almandine.

Putney looked from face to face as the story of Missy and her magic and the flu unfurled. At last she said, “My brothers and I are going to perform in the holiday program at school.”

The conversation about the flu came to an end. All eyes turned toward Putney. “Perform?” repeated Mrs. Clavicle.

“On their musical instruments,” said Almandine proudly.

“Oh, my,” said Auntie Columbia. “All three of you play?”

“Piano, flute, and guitar. I play the guitar.”

Grandmother’s eyes shone. “And what will you be performing?”

“Two songs. The first—”

“Two!” exclaimed Grandfather. “Imagine.”

“So talented,” murmured Mr. Clavicle, who had put down his fork and stopped eating.

“The first,” Putney began again, “will be ‘Up on the Housetop.’ The second will be ‘Frosty the Snowman.’ Benny wanted that one. And then I’m going to play a guitar solo. Probably a Beatles song.”

The flu was forgotten. Missy was forgotten. Even Almandine was a little forgotten.

“You must bring your guitar over sometime and give us a private concert,” Nana said to Putney.

Putney turned to Almandine. “Maybe I could play ‘If I Had a Hammer’ and you could sing along with me.”

Almandine was familiar with the song all right, thanks to the Minstrels, but she hung her head because her entire family knew that her singing sounded like mooing. There was a little silence, and then Grandmother said brightly, “We’ll be sure to attend the holiday program, Putney.”

“Yes, all of us,” added Auntie Adelaide.

“I’m going to be a snowflake in our class play,” Almandine reminded her family.

“Lovely, dear,” said Mr. Clavicle.

The next week report cards came out. “Straight Bs again,” said Almandine with relief when she and her parents logged on to the website.

Putney got straight As. Luckily, the Clavicle adults didn’t ask about her grades. But the next time Putney sat down around the fancy dining table and placed her napkin in her lap, she told Almandine’s family that after Christmas she and her brothers were going to fly by themselves all the way to California to visit their grandparents. “We just found out about the trip,” she said. “We’re so excited.”

“You’re going by yourselves?” Almandine repeated. “Aren’t you scared?”

“Oh, no. We’ve done it before.”

“What? Flown, or visited your grandparents in California?”

“Both.”

“My,” said Mother.

The next evening, Almandine was seated around the Cadwalladers’ table, eating macaroni and cheese from a paper plate, Harry the beagle drooling pleasantly on her ankles, when suddenly she found herself saying, “Next summer my friend is going on a trip down the Nile River.”

“Really? Cool!” exclaimed Joseph.

“Yeah, cool,” said Putney. “Which friend?”

“Um, you don’t know her. Her name is … Candy.”

“Candy. That’s a funny name.”

“She’s going to go animal watching and see gorillas and pandas.”

“On the Nile?” asked Mr. Cadwallader.

“I believe so,” Almandine replied primly.

The next night, when Putney was at the Clavicles’ again, she didn’t even wait for the food to be served before she said, “Almandine told us about Candy’s trip to Africa.”

“Excuse me?” said Father.

“Who’s Candy?” asked Grandmother.

“You know,” said Almandine, sounding faintly cross.

Putney looked from face to face to face.

“My friend. Candy,” said Almandine.

Mother frowned. “Do we know her? Who are her parents?”

“She’s just … at school.”

“She isn’t in our class,” spoke up Putney.

“So what? She’s still going on a trip down the Nile. To see the pandas and jungle animals.”

“That doesn’t sound quite—” Grandfather began, but stopped himself. “Well, that will be some trip,” he said after a moment.

Almandine looked thoughtful, then added, “And she’s going all by herself.”

Later that week, when the best friends were eating dinner at their own houses for once, Almandine suddenly announced to her family, “Guess what. Today during art, Mrs. Hambly said I made the best painting in the class, and she, um, hung it by the front entrance of school … so it’s the first thing anyone sees when they walk through the door.”

“Honey, how wonderful!” exclaimed Auntie Columbia.

“We’ll have to drop by school so we can see it,” said Father.

“I’ll take a picture of it,” said Nana.

“Well,” said Almandine, “it might not be up for very long.”

“Then we’ll go first thing in the morning,” said Father, smiling.

“On our way to work,” added Mother.

“Oh, no,” said Almandine. “It might have been taken down already. It was just a sort of, um, one-day honor kind of thing.”

“Odd,” murmured Grandmother.

“But still it’s an honor,” said Mother.

* * *

Three miles away, in the right-side-up upside-down house, Missy Piggle-Wiggle stood at her front window, looking over the top edge of the quarantine sign, and sighed. Lester, who was sitting on the couch holding a lukewarm cup of coffee, glanced at her.

“Someone will be calling soon,” Missy told him. “I sense a problem somewhere. Someone needs my help.” She sighed again as Lightfoot floated out of the parlor and into the hallway, bobbing gently against the ceiling like a balloon. “No sign of the Effluvia letting up,” she added, “although I still feel right as rain.”

* * *

In the Clavicle home later that evening, the adults kissed Almandine good night one by one, and then gathered around the table in the dining room.

“There’s no one at school named Candy,” Father announced. “I’ve asked around.”

“I’d be surprised if a painting by Almandine was hanging by the front door today,” said Nana.

“Do you know what she told me after dinner?” asked Mother. “That on the way home from school today, she found a giant diamond on the sidewalk but that she left it where it was in case its owner came looking for it.”

“She told me,” said Auntie Adelaide, “that last year she found an injured dog and saved its life.”

“Tall tales,” said Grandfather. “Every single one of them.”

“She’s never lied before,” said Mother.

“Well, it has to be stopped,” said Father. “Who knows what lying could lead to. A life of crime.”

“I hardly think she’s a criminal,” Mother replied. “But I’m not sure what to do about this.”

“Punish her?” suggested Auntie Columbia weakly.

No one could bear the thought. Almandine had never before needed to be punished. The adults sat silently around the table until finally Mother said, “I suppose we could call Missy Piggle-Wiggle. That’s what all the parents do when there’s a problem. Tricia Grubbermitts was telling me about the miracle Missy worked with Louie.”

“And,” added Nana, “Missy cured those insufferable Forthright children of their whining.”

“I’ll call her right now,” said Mother.

When Missy’s phone rang, she wasn’t one bit surprised. “Ah,” she said to Lester, “here’s the call.”

Almandine’s mother introduced herself to Missy and inquired politely how the battle with the flu was going. Then, quite suddenly, she burst into tears and cried, “Our lovely Almandine has become a liar!”

“A liar. Goodness. When did this begin?”

Mother paused and thought. “I suppose it began shortly after Putney Cadwallader moved next door. She’s Almandine’s first real friend, and she’s just lovely. So accomplished, too. She plays the guitar and she’s very bright. And bold! She thinks nothing of hopping on a plane without her parents and traveling all the way to California. Why, our Almandine has never even been on a sleepover.”

“Ah. I think I see the problem,” said Missy.

“Really? Do you know Almandine?” Mother was fairly certain that Almandine had never been to the upside-down house.

“I feel that I do,” Missy replied cryptically.

“Well, what’s wrong? What happened to her?”

“And I know just the cure,” Missy continued.

In the background she could hear a voice, presumably the voice of Almandine’s father, say, “We’ll do anything.”

“Do we give her pills? A tonic?” asked Mother.

“It’s easier than that. A simple air freshener. Just hang it somewhere in your house and let it do its work.”

“Our house is quite large,” said Almandine’s mother uncertainly.

“I’ll give you two, then. Can someone pick them up tomorrow? I’ll leave them on the porch.”

When Missy had finished the call, she sat thoughtfully in a right-side-up chair for a few moments. Penelope flapped into the room. “Liar, liar, pants on fire!” she squawked.

Missy smiled. “But the problem isn’t Almandine’s,” she told her.

* * *

The next morning Missy carried a small paper bag to the front door. Inside were two bars of something that looked like soap and smelled pleasantly like Christmas—pine and cinnamon and peppermint. Attached to each was a red ribbon for easy hanging. The air fresheners, which did not have labels, had come from the dark recesses of Missy’s cabinet, where the cures were for things such as Judginess and Comparisonitis, cures that, in Missy’s mind, were intended for use on parents, not children.

Ten minutes after Missy left the bag on the porch, Grandmother Clavicle picked it up, moving faster than usual in order to outrun the Effluvia, and drove the lovely-smelling fresheners back to the house in the country. She hung one in the dining room and one in the second-floor hallway.

She wondered what would happen next.

At first nothing at all happened except that the scent of peppermint made Almandine want a candy cane.

Then two days later, Mr. and Mrs. Clavicle were cleaning up the kitchen after dinner when Mr. Clavicle suddenly said, “Did you know that Ellie Cadwallader plays the guitar just like her daughter? Turns out she’s Putney’s music teacher.”

Mrs. Clavicle handed him a dishcloth. “That house certainly attracts musicians.”

“Ellie has even played professionally. I ran into her at the bank today, and she told me all the places where she’s performed.”

Almandine’s mother tried to think of something interesting that she could mention.

“Imagine performing in New York, in Paris, in Vienna,” her husband went on.

“Did I ever tell you about the time,” began Mrs. Clavicle, “that I caught a five-pound fish?”

“When you were in second grade?”

“Well, yes.”

Almandine’s father lifted his head and sniffed. “I do like the scent of Missy’s air freshener. I wonder what it’s doing.”

The day after that, Saturday, Mrs. Clavicle looked out the front door and caught sight of Putney’s father raking a flower bed in his lawn. A box of tulip bulbs sat beside him. She hurried into the Cadwalladers’ yard and looked approvingly at the bulbs.

“I do all the gardening myself,” Mr. Cadwallader informed her. “Don’t hold with gardening services.” When Almandine’s mother peered into the carton, he added, “There are a hundred and fifty bulbs in there. Next spring this yard will look like Holland.”

“How lovely,” said Mrs. Clavicle approvingly. She hurried home to report this to her husband. “The Cadwalladers’ yard will be the showpiece of the neighborhood come spring! And Robinson does all the gardening himself.”

“I could do our gardening if I had the time,” said Mr. Clavicle.

“No. You couldn’t. Remember the cactus? We barely even had to water it, and it died.”

Over the next week the names Ellie and Robinson Cadwallader seemed to be mentioned frequently in the Clavicle home.

Ellie decorated Putney’s house with the most tasteful lights Mr. Clavicle had ever seen.

Robinson brought over homemade Christmas cookies that were the best Mrs. Clavicle had ever eaten.

Ellie could make things with a needle and thread that were fancier than anything Mr. Clavicle had seen in a store.

Robinson shoveled his own driveway after the first snowfall and announced that he didn’t hold with plowing services any more than with gardening services.

And on and on and on.

After dinner one night, Almandine’s father set out a chocolate torte he had picked up at the bakery on his way home from work. Mrs. Clavicle put a bite in her mouth and said, “Mmm.”

“I know, I know. Robinson could probably make a better one,” muttered Mr. Clavicle from the other end of the table.

“Dear, I said, ‘Mmm.’ I love this. Why are you bringing up Robinson?”

“Well, you did say you thought his cookies were good enough to get him on The Great Baking Championship.”

“I was paying him a compliment.”

“It sort of sounded like you think I can’t bake.”

“I have an idea!” said Grandmother brightly. “Why don’t we leave the dishes for later and sing Christmas carols in the living room?”

Mrs. Clavicle glared at her husband. “No. I’m afraid amateur music won’t do.”

Almandine stared down at her plate. “I’m sorry I moo when I sing.”

“Oh, no, darling! That isn’t what I meant.”

“What did you mean? We all know I moo. And anyway, Father, why do you care if you can’t bake? You’re the best storyteller I’ve ever heard.” Almandine turned to her mother. “And you always recommend the best books. Your recommendations are even better than Ms. Porridge’s.” (Ms. Porridge was Almandine’s teacher, the one who had suggested she read Understood Betsy.)

After Almandine went to bed that night, Mr. and Mrs. Clavicle sat by the Christmas tree, smelling pine.

“Is that the tree or Missy’s air freshener?” asked Mrs. Clavicle.

Mr. Clavicle shrugged. There was a little silence before he said, “I know what you’re thinking, dear. I’m thinking it myself.”

“Then I’ll say it straight-out. We’ve been comparing each other to Putney’s parents, just like we compared Almandine to Putney.”

“It doesn’t feel very nice.”

“Plus, what’s the point?”

“I have an idea,” said Mr. Clavicle, and he got out a piece of paper and a pen.

When Almandine awoke the next morning, she found something taped to her mirror. She pulled it off and crawled back in bed to read it. It was a list:

Things We Love About Our Daughter

1. She’s the most cheerful person we know.

2. She’s a hard worker.

3. She tries her best.

4. She secretly does nice things for people.

5. She’s a good friend.

6. She’s kind to animals.

The list went on for two pages and was slightly longer than the longest list Almandine had ever made. She read it through twice, then ran downstairs and hugged her parents. “Thank you,” she said.

Suddenly she raised her head and sniffed the air. “What happened to Missy’s freshener?” she asked. “I don’t smell it anymore.”

“Neither do I,” said Mrs. Clavicle.

“Neither do I,” said Mr. Clavicle.

Almandine ran into the dining room. “It’s gone!” she exclaimed. “Only the ribbon is left.” She ran upstairs. “This one’s gone, too,” she called.

“Oh dear,” said Mr. Clavicle. “I hope Missy didn’t expect us to return them.”

“Well, anyway,” added Mrs. Clavicle, “I think they did the trick.”

Across town, Missy, who was tidying up her bedroom, suddenly sniffed the air. “Ah. Pine and cinnamon and peppermint. I believe the Clavicles have been cured,” she said, and she plumped her pillow with satisfaction.