This essay comes from a fourteen-page holograph manuscript in Frye’s Notebook 39, which is archived in the Northrop Frye Fonds at the Victoria University Library, University of Toronto (1991 accession, box 26). Most of the notebook is devoted to Frye’s preparation for teaching two first-term courses, one in the English literature of the sixteenth century; the other, of the seventeenth. He outlines a “tentative syllabus” for both. The present paper is found at the end of the notes for the sixteenth century, and it is preceded by seven pages of notes devoted mostly to aureate diction and serving, it appears, as groundwork for writing the paper. Whether the paper is complete is impossible to know with certainty, but the fact that the notes that precede it end with Skelton, which is where the paper concludes, suggests that the essay does end rather than simply stop. The date of the paper is uncertain. My guess is that the notebook is from the 1940s. I have transcribed the manuscript as Frye wrote it, editing it with only a light touch: I have expanded most of his abbreviations, spelled out ordinal and cardinal numbers, italicized his underlinings, given the paper a title, and added a few notes. The first part of the paper has numbered divisions. Although Frye abandons this practice about halfway through, I have retained the numbers that he used to mark the sections. While I have been squinting at Frye’s hieroglyphic scrawl for almost twenty years, his orthography occasionally continues to confound. There are two or three places in the manuscript where I have failed to decipher his words. These have been marked with question marks within square brackets. All other material in square brackets is an editorial addition.

“Intoxicated with Words” first appeared in the University of Toronto Quarterly 81, no. 1 (Winter 2012): 95–110. Copyright © University of Toronto Press Incorporated 2012. Reprinted with permission from University of Toronto Press (www.utpjournals.com).

1

In English literature there has never been a time without a fashionable poetic diction, at any rate since the death of Chaucer. To trace the steps whereby the fifteenth-century aureate diction grows into the inkhorn terms of the Elizabethans and the archaizing of Spenser is our present task, but the subject could be extended to the Baroque conceit, to the grand style of Browne and Milton, to the antithetic diction of Dryden and Pope, the rise of the eighteenth-century “kenning” with Thompson and Gray, the evocative phrase of the Romantics, the mot juste fetish of the later nineteenth and earlier twentieth centuries, and the surrealist psychological conceit of today. It would be possible to show that every such poetic diction grew out of the earlier one by the simple process of revolting against it. Such scope is necessarily beyond us. But so long a reign implies that poetic diction has very deep roots in English culture, and to find those roots we should have to go back at least to the fall of the Roman Empire and the beginning of the Dark Ages. At that time an intense and rather naïve verbalizing was in full swing. This, again, developed out of silver Latin, and so back to the Homeric epic, which is as far as we can go in demonstrating that there is nothing new under the sun. But the great migration did bring about a far-reaching change in Latin literature. Latin had, at least since Tertullian’s time, been doing some very un-Ciceronian and un-Virgilian things, but it wasn’t until Goths and Lombards and Franks and Anglo-Saxons finally took charge of Europe that the direction of its development finally became obvious. The arts now acquired a quality described by the French as barbarique, which may be translated “something we can’t be bothered trying to understand.” At the court of Theodoric in Ravenna there were four men who may be taken as symbols of this new cultural development. One was Theodoric himself, hero of Teutonic sagas and mentioned as a matter of course in Widsith, or the first vernacular poem. Another was Boethius, with his great dreams of translating the whole of Plato and Aristotle, for popularizing Ptolemy, Euclid, and Pythagoras, who transmitted to posterity not quite this, but a kind of epitome of the Classical attitude to life. The third was the unknown mosaic artist who designed the Mausoleum of Gallo Placidia, and who, like Boethius, shows us the culture of the Classical world purified of its decadence by Christianity. The fourth was the Goth Cassiodorus, of great importance in the history of education and one of the men who made it possible for the monasteries to preserve learning. Cassiodorus it was who invented the “High style, as whan that men to kynges write” [Chaucer, “Prologue to The Clerk’s Tale,” l. 18]. I wish I had more time for him: he was a musician, and had the same feeling for the infinite mystery which we (that is, I) have found so often in English: in Davies’ Orchestra, Cowley’s Davideis, Browning’s Saul, Milton’s At a Solemn Music. And because of that not only is he ready on any occasion1 to talk about the music of the spheres and universal harmony and rhythm, showing the capacity for expanding allegory, which is so precious a heritage of medieval poetry, but he becomes intoxicated with words as pure sound, making them echo and call and respond through his turgid sentences:

Hinc etiam appellatam aestimamus chordam, quod facile corda moveat: ubi tanta vocum collecta est sub diversitate concordia, ut vicina chorda pulsata alteram faciat sponte contremiscere, quam nullum contigit attigisse. [Cassiodorus 90].

[Consequently, we also value the so-called chord, inasmuch as it moves the heart easily: when a harmony of notes has been combined, in such a way that a nearby chord, once touched, may make another one, which did not happen to have been touched at all, tremble by itself.]

2

Echoing of sound means, in poetry, rhyme and alliteration; in prose, euphuism in its broadest sense, for the ancestry of euphuism comes down from Cassiodorus without a break. But such echoing is meaningless without accented rhythm, which begins to dominate European poetry from Iceland to Greece within a few centuries. And with this birth of movement and sound comes verbalism, the feeling that words do not define meaning or clarify images so much as pronounce incantations and evoke mysteries. The notorious obscurantism of Pope Gregory the Great can perhaps be read as in part a healthy reaction against the high style of Cassiodorus, but the three atrocious puns which prelude the Christianizing of England do not promise much for that country in the way of classic simplicity. Nor was Gregory that sort of man. Shall I go or stay? he asks himself at a crisis in his career. Locusta: stay where you are: what could be plainer?2 A word is not a counter: it is a numen, a rune; it brings us to the threshold of an unknown but logically constructed other world. And this is what Old English writers feel, whether they write in Latin or the vernacular. Aldhelm of Malmesbury constructs a poem in the form of a double acrostic, initial letters, reading down, making an extra hexameter, final letters, reading up, another.3 Or he will write a sentence of sixteen words of which fifteen begin with “p.” When he’s finished, what has he, a puzzle? Not at all. He has an abraxas, a talisman or charm, and its twisting, grotesque, involved lines imprison a mysterious power. So do the tangled lines and mangled words of the Lindisfarne Gospels.4

3

All this has nothing to do with barbarism. We must not forget the third man of Ravenna, the anonymous artist. His art we call Byzantine, and Anglo-Saxon literature is, like Anglo-Saxon art, the most precocious advanced Byzantine and the most precocious Romanesque art in Europe. When it is conventional, as in Cynewulf, it is purely Byzantine; when original or else experimental, as in Beowulf, it approaches the Romanesque. This means that its conquest over work is fairly complete.5 In The Wanderer we can see alliteration reinforced by a sensitive feeling for assonance. The author knows as well as Milton how to produce an effect of gloomy terror by alliterating on “w,” and he knows how to organize a sound pattern. And, of course, not only the best lyrical Old English poetry, the riddles, but the lyrical feature of Old English poetic diction, the kenning, consist in describing some essential things about Old English life in terms of its function, avoiding its name and suggesting by its avoidance that the name is a numen, something charged with unknown potency.

4

The comparatively classical and restrained vocabulary of the best medieval poetry is due largely to the fact that it is either southern and has rhyme without much alliteration, or northern and has alliteration without rhyme. Both traditions retain the musical tradition stemming from Cassiodorus, but it is only when alliteration and rhyme come together, as in the Pearl, that the sheer effort of hunting for words produces the evocative effect of poetic diction. “To þenke hir color so clad in clot” [Pearl, l. 22] is an example. Chaucer and Gower, on the other hand, are remarkably free from poetic diction, but like all who have achieved this freedom, their work shows an autumnal ripeness, an inimitable maturity. In Gower’s story of how a serpent and an ape could feel a gratitude toward Bardus that the human being Adrian did not feel, the sense of the rightness of instinct and the wrongness of intelligence, which weighs like an incubus on a more melancholy poet like Vaughan and leads him to think that Nature is nearer God than man, is given a humorous, paradoxical twist by the delicate ambiguity of the word “unkind,” which means both wrathful and unnatural, applied to Adrian.6 Chaucer knew all about poetic diction, but the Franklin declines to use it [“Franklin’s Prologue,” ll. 17–18], and the Clerk is warned that he must not use it [“Clerk’s Prologue,” ll. 15–20]. Chaucer is essentially a poet of occupatio, of a refusal to describe things positively, in terms of movement and sound. The Knight’s Tale rises to its tremendous climax, the funeral rites of Arcite, on a series of negatives. And similarly the feeling for horror and grotesquerie, which takes an evocative poetic diction to describe, is not Chaucer’s. The most horrible episode in Chaucer, January’s wooing of May in the work of the great coming-of-spring passage in the Song of Songs [The Merchant’s Tale, ll. 2029 ff.] is a refined and intellectual horror, not in the sound of the verse. There is little mystery and little feeling for an unknown in Chaucer: his terror of the infinite is certainly French and is almost Greek. His world is one controlled by easily understood and predictable laws. “Deores wiþ huere derne rounes” [Animals with their secret cries]—that simple line, by a contemporary lyric poet [Brook 44], brings us into a whole new dimension of experience, and does so by its careful and sensitive adjusting of vowels and consonants and its deliberately vague language—in short, by its use of musical poetic diction.

5

Even before Chaucer’s death a number of events conspired to make any direct imitation of him impossible. A contemporary, Thomas Usk, was even driven to experiment with prose. Most of these events are connected with the changes in the language. Inflections were disappearing, which meant chiefly that the final “e” dropped out. In Chaucer’s line “But trewely to tellen atte laste” [General Prologue, l. 707] four of the eleven syllables would not be available to a later writer. The exact connection between the vowel shift which took place at this time and the dropping of inflections is difficult to determine, there being at present no psychology of phonetics, but they did coexist, and as vowels were frequently lengthened when the “e” was dropped, the tendency was tone and resonance, and the total effect was to give the line of English poetry a weight and solidity, which has no doubt made it more powerful, and poets of Chaucer’s eminence in some respects less restricted, while it destroyed the Middle English lightness of touch. The lightness of Chaucer, of Sir Orfeo, of The Owl and the Nightingale, has disappeared from the language forever with the levelled inflection, which made these poems possible. A remarkable syntactic development, too, the rise of increased use of relative pronouns, prepositions, and conjunctions, the emergence of auxiliary verbs, the distinguishing of a progressive tense, was at the same time giving the language its present analytic form. In poetry any syntactic development means that the rhythm of the poet’s meaning will come more and more to syncopate with the rhythm of his metre. Chaucer’s followers, then, had a heavier line to handle, which they would have to flog along with sharp linear accentuation to make move, and they were coming more and more to think in a way in which the order of words was everything and the inflections subordinate to it.

Two other phenomena are connected with this. One is the rise of a conception of standard English, according to which one dialect comes to be spoken and written by educated people all over the country while others come to be restricted to the peasantry and rural population. The word “rural” itself is a coinage of Lydgate’s. Now as a dialect expands to standard speech, it becomes increasingly eclectic in its choice of forms. Thus, the eclectic tendency in writing a language, though at the opposite extreme from a dialectic one, is a logical development from it. Chaucer was a dialectic writer, Spenser the most eclectic in the language, yet Spenser considered himself a disciple of Chaucer, and between the two poets are the two centuries of continuous expansion of East Midland over England. During those two centuries, however, another process had been at work, the vernacularizing of culture. With the increasing use of English for works on science, philosophy, and religion comes the necessity for incorporating bodily the terms which up to that time existed only in Latin. This is marked even in Chaucer. Chaucer tries hard to make his Boethius and Astrolabe as simple as his poetry, even dedicating the latter to a child in order to force himself to write simply. But even so, he cannot help introducing technical terms like attention, duration, fraction, diffusion, and position to the language. And the fact that he could do so indicates a development in the analytic consciousness of the English mind.

6

In short, it must have been fun to make these new words. The contemporary books on rhetoric recommend ficcio (coining words), transumptio (using words with different meanings), and introductio (borrowing). The new words must have been accompanied by a feeling of increased mental power. Take an analogy from our own time. Until the rise of psychology there were no words for the mental phenomena that subject deals with, or, if there were, there were only timid words like “hunch” or “quirk.” But when “psychopathic complex,” “traumatic neurosis,” and the like came rumbling in, everyone rushed to play with the new toys, so that psychologists now will have nothing to do with “soul,” “will,” or “instinct,” even when it is impossible to see what else they can mean by the polysyllabic cacophonies they do use. Similarly, when Mr. T.S. Eliot writes, “The young are red and pustular / Clutching piaculative pence” [Mr. Eliot’s Sunday Morning Service, ll.19–20], we nod sagely and think how suitable the precise use of the technical terminology of medicine and theology is to this age of advancing science. The imagery, we feel, is concrete, the emotion carefully controlled. We should be wrong, of course: Mr. Eliot’s language here is as “aureate” as anything in Hawes. But it’s grand fun.

It must have been exciting for the fifteenth century too, surely. The lists of words added to the language by Lydgate are practically all essential today, which implies that his feeling for words was a perfectly genuine one. The words beginning with “a” attributed him to him are: “abuse,” “adjacent,” “adolescence,” “aggregate,” “amote,” “arable,” “attempt,” “auburn,” “avale,” “avaricious.” Two only have gone out of use. The paint has worn off the rest: they are faded and dull, and a Times leader would be better for them than poetry: a newspaper would be a better foil for them than a book of poems. But at the time, they were new, and helped to imp the wings of English literature. The one word constantly associated with them is “colour.” It was as natural for them to speak of “colours of rhetoric” as for us to speak of “shades of meaning.” Here is a very revealing passage from Lydgate’s Troy Book. He is speaking of Chaucer.

Whan we wolde his stile counterfet,

We may al day oure colour grynde & bete,

Tempre our azour and vermyloun:

But al I holde but presumpcioun—

It folweþ nat, þerfore I lette be. [Bk. 2, ll. 4715–19]

Every time Lydgate uses a learned work he thinks of it as a splash of colour, a bit of bright red or blue. And his poetry is intended, like a Cézanne water-colour, to evoke the feeling of outline by means of these spots of brightness. This does not mean, of course that his poetry is joyous. Whatever one’s attitude to words, a writer like Lydgate, who is particularly fond of heavy and resonant words, whose vocabulary in consequence is usually Latin, and whose use of language is hieratic rather than colloquial, is usually a writer with a deeply serious vision of life. Milton and Browne are later examples. The aureate is par excellence a contemplative style. Lydgate certainly had that: two of his three epics are translations of works which employ the archetypal tragic formulae of the wheel of fortune, the danse macabre, and the psychomachia. What “colour” really is, in poetry, is sound, which brings up the question of rhythm, and this connects Lydgate with the tradition of musical or accented poetry.

7

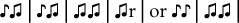

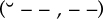

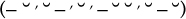

We have said that successors of Chaucer, because of the changes in the language, willy-nilly had to abandon his already conservative line and adopt one with heavier sound and ictus. That was one of the problems in front of Lydgate: how to break up the Chaucerian line. One critic has listed four variants from the normal iambic line (at the moment we shall speak only of iambic pentameter) used so often by Lydgate as to become frequent license forever after in English poetry. One is the extra short beat at the caesura that is called “epic caesura.” We should not go very far without meeting that in English poetry. It occurs in the first line of Paradise Lost. Another is the beheaded line or trochaic first foot, used for quickening the pace, or sometimes, as in Chaucer’s “Whilom” or “Whan that Aprill,” for starting a long poem with a downbeat, as it were. Another is the anapaestic first foot, used for the same purpose of greater speed. The fourth is the so-called broken-backed or Lydgatian line, which from Old English times (when it was type C of Sievers’ five metrical patterns) to our own day has produced some of the most powerful effects in English poetry. Milton’s “Which tasted works knowledge of good and evil” [Paradise Lost, bk. 7, l. 543] is an example. Now if Professor Schick is right in his analysis, Lydgate, in introducing to English iambic pentameter its four most frequent and effective variants, must have had as sure an ear for rhythm as for language. That would make him a poet. Of course he had many other variants, and often his poetry is obviously doggerel. The nearness of its approach to the complete identification of rhythm and sense, which is one ideal of prosody, is a question impossible to solve without more reading of Lydgate than I have done. Besides, a large margin of error will always remain; we know much less about his prosody than Chaucer’s: his metrical principles are infinitely more difficult to get at than Chaucer’s, and in consequence it is perhaps safe to say that unless an autograph turns up we shall never have a text of his work we can feel confident about. Again, the sheer volume of his work implies acres of doggerel, and the fact that so much of it was hack work implies haste and the lack of genuine creative pleasure, in spite of the new words. If we had of Milton only things of the Eikonoklastes or Defensio Prima level, we should find it impossible to say whether an authentic genius was imprisoned in them or not. Besides, he was practically a poet laureate. Lydgate’s Testament looks like genuine poetry, but his personal work is marred by his excessively artificial forms, such as last-line links between stanzas, which do not suit him as they suit the Pearl poet.

On the other hand, the prevalence of beheaded and broken-backed lines in Lydgate does imply, as Miss Hammond points out, that he thinks in terms of half-lines or, at any rate, in terms of a very decisive caesura. As this is also true of Old English poetry, one wonders if two principles of Old English metre also hold good for Lydgate. One is that an extra short syllable or two does not disturb the prevailing metrical pattern: thus Type A, two trochees, would still be Type A if it were two dactyls. If so, perhaps the absence of a reliable text is, though certainly a nuisance, less fatal to appreciating Lydgate than we might at first have thought. The other is that the two halves of the line can be constructed on different metrical principles, which provides a subordinate contrast to the variants from iambic pentameter in the line itself. The result is that when we come to Lydgate from Chaucer or Gower, we have to apply to him the words the minstrel applies to Death in the Danse Macabre:

This new daunce / is to me so strange

Wonder dyuerse / and parsyngli contrarie

The dredful fotyng / doth so oft chaunge

And the mesures / so ofte sithes varie

The caesura is so marked in the Early English Texts Society edition.7 And yet when we look at these lines with their subtle unobtrusive alliteration, we can surely see a deliberate contrast between the strong assured rhymes “strange” and “chaunge,” with their gloomy vowel sounds, and the wavering uncertain feminine ones. And the rhythm, with its alternation of slow creepy spondees like “The dredful fotyng”  and the almost jazzy syncopation of the second line

and the almost jazzy syncopation of the second line  (I think is the way to divide it), suggestive of a grisly Holbeinish scene of leaping skeletons, is certainly the rhythm of genuine poetry.

(I think is the way to divide it), suggestive of a grisly Holbeinish scene of leaping skeletons, is certainly the rhythm of genuine poetry.

This example is singularly free from aureate diction. But aureate diction is essential to Lydgate’s manner nevertheless. Take this stanza:

Problemys of old likenese and figures,

Whiche proved been fructuous of sentence,

And hath auctorité grownded in scriptures,

By resemblaunces of nobille apparence,

Withe moralités concluding of prudence,

Like as the Bibylle rehersithe by writing,

How trees sometyme chase himself a kyng.

This is the opening of The Chorle and the Bird, and the sonorous language is intended to be an impressive prelude, scored for brass, to arrest the ear before the story begins. It has another purpose too. All fables point [to] a moral, and to a medieval mind like Lydgate’s that means that fables indicate the divine and moral laws which forever all human beings experience. That sounds rather pompous expressed in this way, but it is not necessarily so; the discovery of the immensely significant in the trivial is Wordsworth’s procedure as much as Lydgate’s. The difference is that Lydgate’s subtle alliteration (we have noted that twice now) and his arrangement of the deep rune of solemn vowels is intended, by its sound, to suggest the oracular ambiguity inherent in fables generally. The intentionally vague language, too, indicates that region of thought where ideas give out and symbols begin. And the method of unaccented rhyming is taken over from him by such subtle and expert technicians as Wyatt, who is not afraid of such rhymes as “harbour–banner” [The Lover for Shamefastness Hideth His Desire within His Faithful Heart, ll. 1, 4] and from Wyatt to Southwell in one or two poems, after which it disappears until our own day. I suspect Lydgate of being a poet, is all I can say at present. What he mainly lacked, to make him the Beethoven to Chaucer’s Mozart, was the self-conscious egoism supplied by [Thomas] Hoccleve.

Aureate language, like every other form of poetic diction, is bad with bad poets. Lydgate’s use of it is, I think, strained but original. Anyone who doubts this has only to compare him, at his worst, with such specimens as the prologue to Ripley’s Compend of Alchemy. We are concerned at the moment only with good poets, however, and must pass on to the Scottish Chaucerians. The first thing to be said about them is that they have an equal right to be called Scottish Lydgatians. Their line has the Lydgatian stressed accent, the Lydgatian heavy vowels and dropped inflections, the Lydgatian long rolling vocabulary, and a more than Lydgatian use of alliteration. The terrific energy of Dunbar subordinates the most complicated rhyming and inter-rhyming schemes, the most incessant alliteration, to a hammering, pounding accent, and many of his slower poems have to be pulled up by a refrain. Such poems as The Twa Mariit Wemen and the Wedo or The Flyting of Dunbar and Kennedy:

Forflittin, countbittin, beschittin, barkit hyd,

Clym ledder, fyle tedder, foule edder, I defy thee!

[The Flyting of Dunbar and Kennedy, ll. 239–40]

It is not possible to find any poetry in English literature more unlike Chaucer than that, but it is a fairly logical development from Lydgate’s revolutionizing of the Chaucerian line. Hence we should expect to find that Dunbar’s use of aureate diction would be Lydgatian also. Dunbar is, however, the greatest musician that British poetry had up till then produced, and his great sensitivity to rhythm and sound bring out very clearly the essential musical quality of aureate language as a form of poetic diction. True, all Dunbar’s language reflects his sense of musical sensitivity, and he is keenly aware of the peculiar effectiveness of the Scottish dialect for some effects:

Mony sweir, bumbard-belly huddroun,

Mony slute daw and slepy duddroun

[The Dance of the Seven Deadly Sins, ll. 70–1]

is the right sort of noise for sloth (“Sweirness”), and

Sir Gilbert Hay endit has he [Lament for the Makers, l. 67]

shows his easy mastery of the broken-backed line in a less dialectical poem. But it is his use of aureate language that we are concerned with here, and this is so skilful as fully to justify the convention, even if it be denied that Lydgate had already done so. Two qualities of Dunbar’s aureate language are especially important: its capacity for building up an impressive sound pattern and its capacity for expressing the artificial, using that word in its old-fashioned laudatory sense. The former is, of course, simply a development of the less sensitive inter-rhymings of the vituperative poems:

Hale, sterne superne, hale in eterne,

In Godis sicht to schyne!

Lucerne in derne for to discerne

Be glory and grace devyne;

Hodiern, modern, sempitern,

Our tern inferne for to dispern,

Helpe, rialest rosyne.

Ave Maria, gracia plena!

Haile, fresche floure femynyne!

Yerne us guberne, virgin matern,

Of reuth baith rute and ryne.

[A Ballad of Our Lady, ll. 1–12]8

There is nothing quite like that in English poetry: the boldly adapted, altered, transformed, and coined words make the language further removed from ordinary speech than any poetry has been since. Dunbar is writing two languages at once: Latin and English run along in counterpoint, the Latin words producing more of the “ern” sounds, which echo like the clanging of bells, and the English providing most of the alliteration. Parts of it are bad, like the last line, where the forced and far-fetched conceit, added to the intoxication of sound, pushes the strangeness beyond reasonable limits. But it deserves to survive as experiment.

Aureate language is of course highbrow and fitted only for religious allegorical poems. But by Dunbar’s time the May morning vision and the Court of Love allegory were beginning to grow rather old-fashioned, consciously literary, and quaint. Hence when Dunbar uses aureate diction in The Goldyn Targe or The Thistle and the Rose, he does so because he is deliberately trying to give the effect of curious, elaborate artifice. The world of The Goldyn Targe is not a real world but an “anamalit” [enamelled] one [l. 13]. The air is crystal, the heavens sapphire, the summer ruby, and so on:

The birdis sang upon the tender croppis

With curiouse note, as Venus chapell clerkis. [ll. 20–1]

Aureate language therefore falls into its place:

Up sprang the goldyn candill matutyne

With clere depurit bemes cristallyne [ll. 4–5]

And in The Thistle and the Rose, where the subject is admittedly not only allegorical but heraldic, aureate diction is even more restrained and delicate, only touching up an image or two with a suggestion of remote strangeness:

A coistly croun with clarefeid stonis brycht [l. 155]

The same principle is roughly true of Gavin Douglas, but his sense of the aureate is somewhat less naïve than Dunbar’s, and his language gives an effect of far greater unity. It is in Douglas that we first find a favourite effect of Milton, Marlowe, and Sir Thomas Browne, sniffily described by Mr. Eliot as Q9

Forst steirs the stern Mnestheus on ane.

Aureate diction at the present time is out of style in some respects. The man who carefully memorizes the longest words in the dictionary to impress his friends with does not now impress them. Their use is permitted only in facetious writing, and the kind of humor shown in calling a “lie” a “terminological inexactitude” gets more ponderous and unbearable with each new practitioner of it. In literary criticism this means, as we have already seen, an unsympathetic approach to poets who we think have been deceived by the [?] [?] of long words. No poet, not even Lydgate, has suffered from this more than Hawes.

Hawes marks the climax of the aureate tradition, for what had been experiment and discovery to his predecessors was a dogma and a theory to him. It is noteworthy that neither Hawes nor any other poet of his time I know of regards aureate terms as exact, carefully shaded, and distinguished meanings of subtle and abstract ideas. His approach to a conception of poetry is altogether different. To him, there is no use in poetry which merely treats of things: any sane man can see with his own eyes. That is photography, not creative imagination. The really penetrating artistic mind is that which probes beyond the phenomenal world in the mystery of the world behind it. Hawes does not know what kind of a world that is. For that reason it is to be reached by suggestion and symbol. The content of poetry, therefore, is certain to be allegorical, and the meaning of that allegory vague. If we try to pin it down to too definite a meaning, it dissolves into a cloud of words. Poetic diction, therefore, must be completely hieratic and artificial. No one can really understand it, for it conveys not meaning but suggestion, yet it is addressed to sensitive minds who use it as a stimulus to contemplation. The direction of contemplation is given by the form of the complete poetic argument: that is why Hawes puts so much emphasis on order and arrangement. When he says of poetic diction that

The barbary tongue it doth ferre exclude

Electynge wordes whiche are expedyent

In latyn or in englysshe after the entent

Encensynge out the aromatyke fume

Our langage rude to exyle and consume

[The Pastime of Pleasure, pt. XI, ll. 17–21]

he does not mean, we see, that English poetry should be versified Latin: he is not choosing between languages but between kinds of words. “Our langage rude” is not necessarily English but the kind of language we use in describing washtubs and neckties and carrots. Poetic language is mystical (Hawes is far more a poetic mystic than Vaughan or Blake) and evocative. The line “Encensynge out the aromatyke fume” proves that his conception of poetry is a decadent one, and proves too that aureate diction has reached with him the limit of one phase of its development. But to read him sympathetically is to read him with the New English Dictionary at one’s elbow. In such a [?] we must remember that Hawes was, according to the NED, the first to use “elect” as meaning a deliberate choice in preference to everything else: the election of a word to a place in Hawes poetry is not to be made too unconsciously. “Expedyent,” again, has with him not only the meaning of suitable, appropriate to the form, but the obsolete sense of nimble or skillful, and probably as well the etymological one of freed from bondage. This sounds rather niggling, but Hawes seems to want this kind of reading from us.

As we have said, Hawes is the climax of the fifteenth-century kind of aureate diction: after him, nothing was possible but reaction, ridicule, and the creation of a new kind. We have so far tried to avoid defining the word “aureate,” but it seems fair by now to describe it as a habitual use of terms which to those using them seemed “wonder nyce and straunge” [Chaucer, Troilus and Criseyde, bk. 2, l. 24]. We say to those using them, for Lydgate and Hawes had a very much underestimated power of creating or popularizing essential words, and because their innovations were successful, we now regard them as faded. But it is approximately true to say that any writer whose work contains many words imperfectly digested by the English language, whatever their origin, is an aureate writer. Now by Hawes’ time the feeling of the barbaric quality of English as compared with Latin or French persisted in some quarters while it waned in others. In the former the borrowing of aureate terms went steadily on, reinforced by more genuine if often more pedantic Classical learning; in the latter an awakening interest in the possibilities of English combined with a rejection of the old hieratic conception of poetry. This gave two new features to the vocabulary of the latter: one, the increased use of old-fashioned, dialectical, or Chaucerian words from the vernacular itself; the other, the less affected use of terms formerly aureate, which made possible the progress of their assimilation into the language.

In other words, these writers were more simple, downright, and vigorous than their predecessors, though they reaped the benefits of the latter’s ingenuity. As we have seen, they included Dunbar and Douglas, whose alleged use of Chaucerian language is reinforced by the most conservative of English dialects. They also included Rabelais, who ridiculed aureate terms more than once. But the most notable English poet of the group was of course Skelton. This amazing master of words was, as all students of him know, greatly influenced by the medieval Latin lyric, and scraps of Latin float in like the words of the requiem in Philip Sparrow, sometimes used as various Mother-Goose syllables. But this bilingual, wholesale incorporation of Latin means that he is a far more English poet than Hawes, the boundary lines between the two languages being more clearly marked. The Hawes conception of poetry, being medieval, would lead most naturally to a kind of cosmopolitan poetic diction based on Latin, like the language of science today, the technical part of which is equally based on Latin and Greek. It makes scientific works in English comparatively easy for an Italian. But Skelton’s really aureate terms are most successful when humorous, their swelling rotundity punctuated by vulgar words and ideas, their dignity mocked by impudence:

A phoenix it is

This hearse that must bless

With aromatic gums

That cost great sums,

The way of thurification

To make fumigation,

Sweet of reflare,

And redolent of air,

This corse for to cense

With great reverence,

As Patriarch or Pope

In a black cope.

While he censeth the hearse,

He shall sing the verse,

Libera me,

In de, la, sol, re.

[The Requiem Mass, ll. 133–48]