A simple act of kindness is bringing a piece of homemade peach pie to your elderly neighbor. But what if your neighbor can’t eat sweet treats or is allergic to peaches? True kindness requires looking at the world from another person’s perspective. If you were in your neighbor’s position, maybe you would want peach pie, and you might understand that delivering pie would earn praise from your friends and family. But real kindness looks at the world not with your eyes but with someone else’s. In fact, so many acts of kindness are just that: a way to show someone that you understand his or her perspective—you understand the way someone else sees the world.

How good does it feel to know that someone understands, cares, and respects who you are? Beyond money or gifts, it is this feeling of being understood and supported that is at the heart of kindness.

You have the opportunity to help someone feel this feeling. Maybe instead of peach pie, your neighbor would rather have a tomato from your garden. Or if a friend has a problem, maybe you could listen without distraction. Today, practice looking at the world with someone else’s eyes. Then, find a way to show that you see what this person sees. That’s kindness.

600 Acts of Kindness

Alex McKelvey

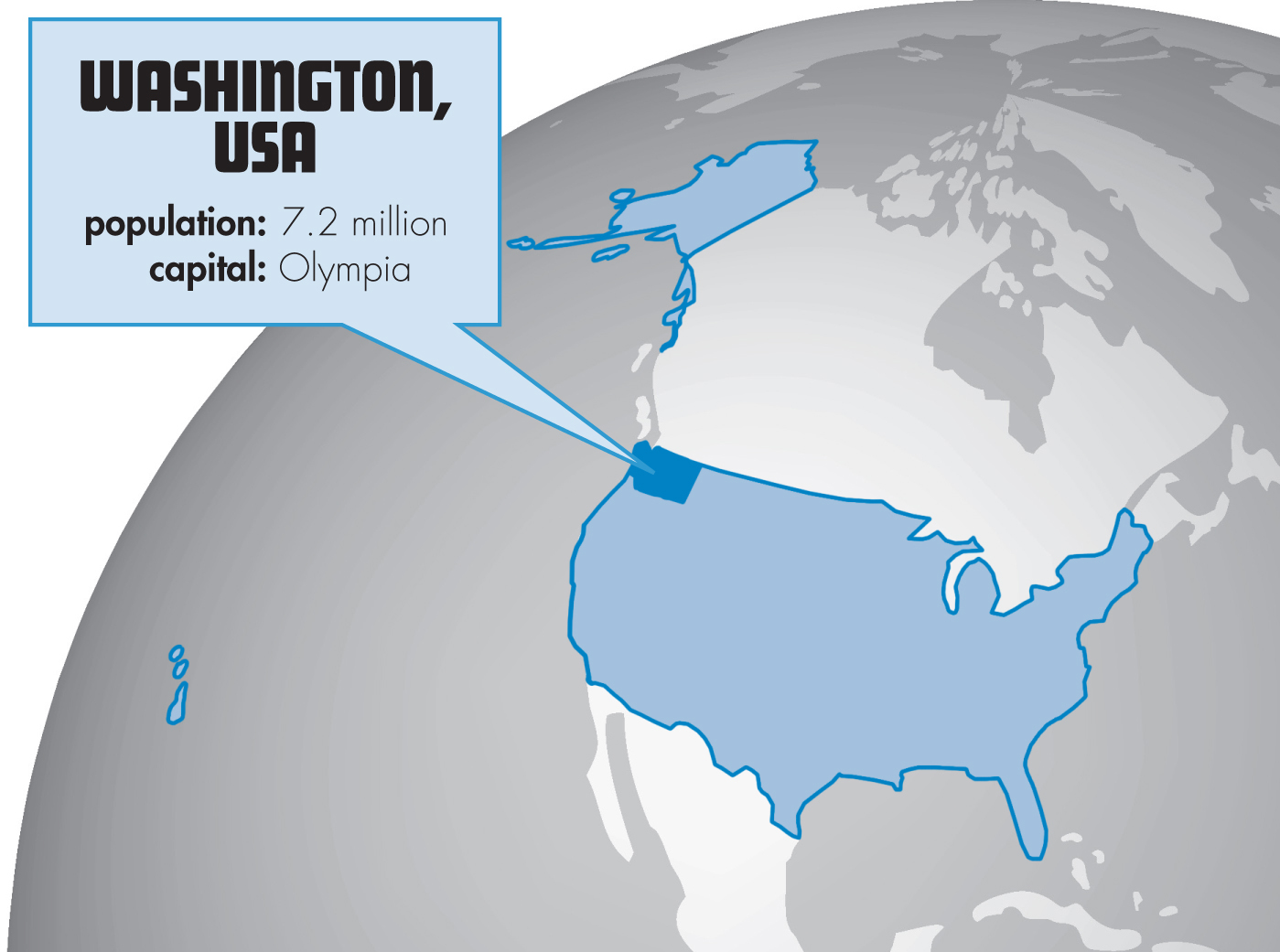

How do you honor someone you love who passes away? Unfortunately, Alex McKelvey of Lakewood, Washington, had to ask herself that question when she was only six years old. That year, her grandmother, Linda, died. Alex enlisted her mom, Sarah, to help her perform 60 acts of kindness on March 22, 2014, the day that would have been her grandmother’s 60th birthday. These nice things went beyond saying thank you after dinner or helping fold the laundry.

“I try to do acts of kindness at home, but they don’t count,” Alex told her hometown newspaper, the News Tribune. “You have to do them for someone you don’t know, or as a surprise for someone you do know, like one of your teachers.”

With her mom’s support, Alex went on a kindness blitz, offering to pay for coffee or ice cream for people just ahead of them in line, and buying toys for the St. Jude’s Children’s Hospital. When they left a big tip for their waitress at IHOP, Alex took a picture of the receipt and posted it to Instagram. The waitress found the picture and wrote, “That was me!!! I didn’t even get a chance to thank them. I’m very grateful to have been part of this. Thank you so much from me and my daughter.”

March 22, 2014, was a long day, but they made it—60 acts of kindness in all! It went so well that Alex didn’t want to stop there. She talked her mom into helping her complete 600 acts of kindness before what would have been her grandmother’s next birthday in March 2015.

Off they went. Alex became known as the “napkin girl” at the Rescue Mission in Tacoma, Washington, where it was her job to hand out napkins when she volunteered every week. And she has led an effort to repaint the youth room at the YMCA in her hometown. But most of her acts of kindness don’t take many days or hundreds of dollars. Some require only a couple words or a smile.

In March 2015, Alex was closing in on her goal of 600 acts of kindness. She’d spent the year, day in and day out, checking off her list and she wanted to finish strong. So, just like Alex and her mom had started the year of kindness with a day of 60 good deeds, she wanted to cross the finish line with another big day, this time with 61 acts of kindness. Alex knew she would have to get organized, so she made a list and posted it to Instagram with the hashtag #ForLinda, her grandmother’s name. Here are some of the things she planned for that day.

Hold the door open for someone, shake someone’s hand and thank him, leave a thank-you note with a small treat for the mail carrier, pick up litter and throw it away, give away hugs, give a compliment, deliver homemade cookies to a fire station, leave kindness quotes in random places, return shopping carts, mail a letter to a friend, post positive thoughts on a mirror where others can see, brighten someone’s day with flowers, tell someone I love them, leave lucky pennies on the ground for others to find, leave a note in a random book for someone else to find, hand out balloons, tell a joke to make someone laugh, call my grandparents, give someone a high-five and tell her something positive about herself.

Phew! That’s a big day! And that’s only part of the list. The trick is, Alex did more than list these things. She actually did them. All of them and more!

Not many of us will decide to be Alex. Can you imagine doing half the things on that list in just one day? Luckily you don’t have to. In fact, you don’t have to do anything on that list. But, today, why not pick one of these small acts of kindness and give it a try? You might find the smiles you create showing up on your own face, too.

Story photo credit © ROBERT M. BRALEY JR. | DREAMSTIME.COM

@OsseoNiceThings

Kevin Curwick

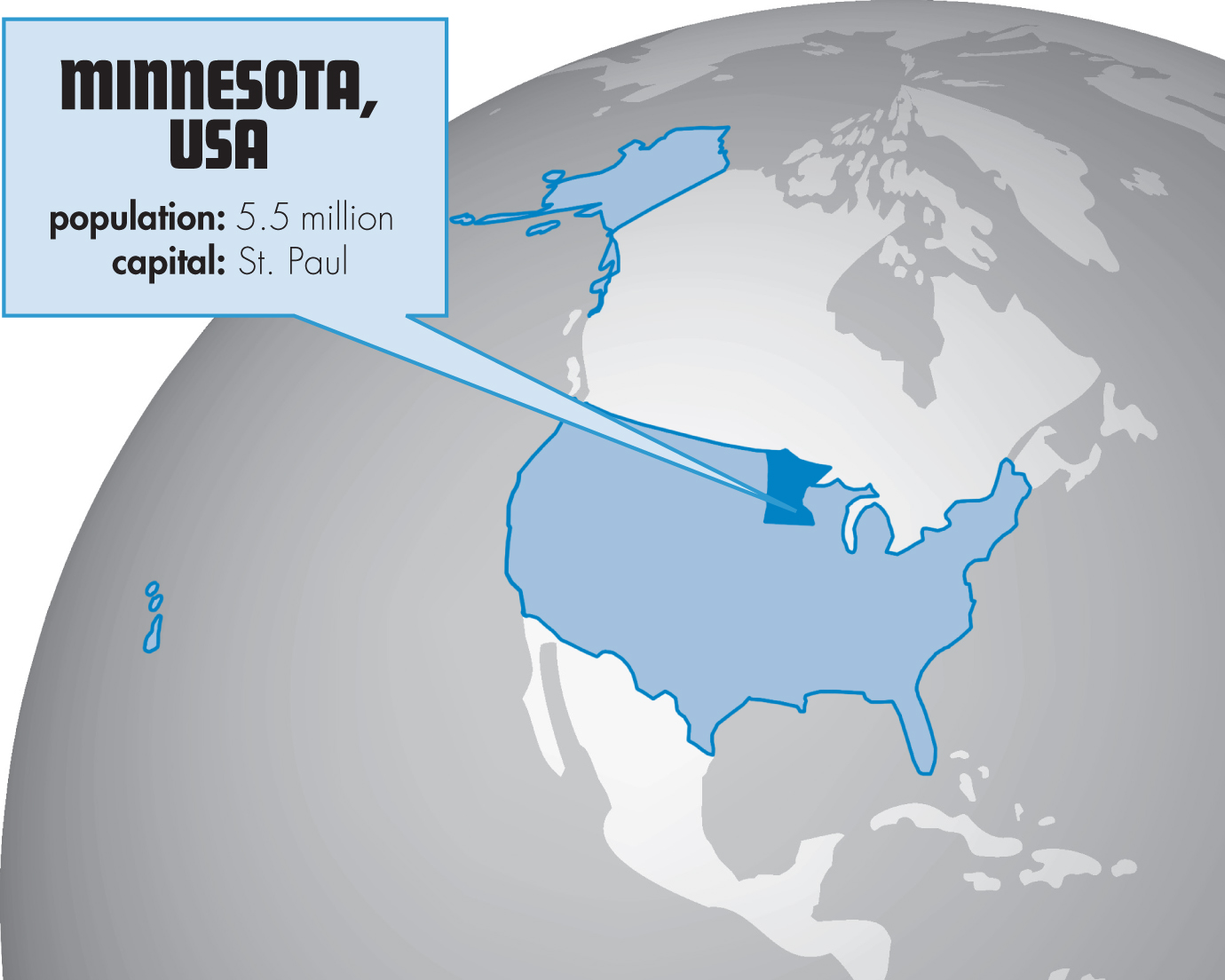

You know about cyberbullying. It’s when people go online or use their cell phones to text or post mean things about other people. Online, people can say mean things anonymously so they don’t get in trouble and they don’t have to live with the consequences of the things they say. If you’re the target of cyberbullying, you might not even know who your bully is. In 2012, that’s what was happening at Osseo Senior High School, in a suburb just northwest of Minneapolis, Minnesota.

“In July, between my junior and senior years, some Twitter accounts were made. Things like ‘Osseo Rumors,’” 16-year-old Kevin Curwick said at the time. “Essentially they were anonymous attacks on students at my high school. You could be walking down the hall, and you would look at the people around you . . . even at your best friends, and you don’t know who is tweeting these disgusting and awful things about you.”

Kevin was quarterback and captain of the football team, captain of the Nordic ski team, president of the National Honor Society, and active in the junior rotary. Everyone knew him, and for the most part, people liked and respected him. So you can imagine that if Kevin had taken a stand against cyberbullying and told his friends—the popular kids at school—to knock it off, they might have listened just because of who he was. After all, Kevin was popular and powerful, and that’s how it usually works in high school.

Instead, Kevin decided to fight fire with fire. Or maybe it was more like fighting fire with water. What’s the opposite of cyberbullying on Twitter? Well, to Kevin, the opposite was cyber kindness, in this case anonymous Twitter praise. Kevin started the Twitter account @OsseoNiceThings. And he didn’t tell anyone he was behind it. Here are some of the first things he wrote:

“There are too many good people in Osseo to have any one of their reputations ruined.”

“Shout out to the incoming sophomores! Help make Osseo what it is #thebest.”

“Who has made your experience at Osseo better? Respond and I will retweet for everyone to see.”

“Clarke Sanders. If she can’t help you feel like a part of Osseo, no one can.”

“Only man at Osseo to be known to pull off short shorts. Great runner. Great friend. Quinn Gamble.”

“I knew these people and I knew their talents,” Kevin says. “And once I started tweeting about them, within a week all those other accounts—the stuff like Osseo Rumors and Osseo Truths—they had all closed.” Kevin noticed that everyone was taking part. If @OsseoNiceThings tweeted about a band member, the football team would retweet it. If it was a nice thing about somebody on the girl’s golf team, people from the National Honor Society would retweet it.

People outside Osseo started to notice. It started with this tweet: “@OsseoNiceThings Hey. I’m Jay Olstad w/ KARE 11. I have a question for you. Can you email me? Thanks!” Jay was a reporter from a local television station, and when Kevin sat down for an interview that was broadcast on TV, the cat was out of the bag: Osseo Nice Things was no longer anonymous, and everyone learned that Kevin was the person who had started it.

“One thing I stress is that, sure, everybody’s crediting me with this idea, but it was anonymous for the first month it ran. The high school took this and ran with it. It didn’t need to be me. I absolutely think anybody could have done this. And it could have happened anywhere,” Kevin says.

One of the people Kevin connected with through Osseo Nice Things was Dr. Michele Borba, parenting expert for TV shows like The Today Show and The View and The New York Times. Kevin talked with Dr. Borba for a book she was writing about how social media promotes mean and self-degrading comments—we share little snarky things that let us laugh at people rather than with people.

“But Osseo Nice Things showed how much hunger we had for kindness,” Kevin says.

When summer break ended and Kevin and his classmates returned to school, the difference was obvious. “In the cafeteria, there were circle tables that had always been kind of reserved for seniors and jocks and the popular kids, and the surrounding areas were for underclassmen and less popular people. That fall, after Osseo Nice Things, if you walked into the cafeteria, you couldn’t see those categories. It was change from social media that went way past social media,” Kevin says.

“Whether on Twitter or in person, you can always choose kindness. When you’re kind, you build Osseo Nice Things in your life,” Kevin says.

How long do you think it takes to start a Twitter account? Maybe 90 seconds if you’re a slow typist? Do you wish there were more “nice things” at your school? If you know how to do it (and it’s okay with your parents!), why not try to bring a little more kindness to your community?

Story photo credit © MIRCEA BEZERGHEANU | DREAMSTIME.COM

Nice Guys Finish Last

Conner Long

For some people, competing in triathlons is about pushing themselves to the limit. For others, it’s about winning. For Conner Long, competing in triathlons is just about crossing the finish line. But almost every time he swims, bikes, and runs a race, he finishes last. That’s because he tows, pulls, and pushes his younger brother, Cayden, who was born with cerebral palsy.

About one in 500 babies is affected by cerebral palsy, a condition in which parts of a baby’s brain don’t work. When Cayden was born, the doctor told the family that Cayden would never walk or talk. But Conner Long wasn’t about to let his brother be left out.

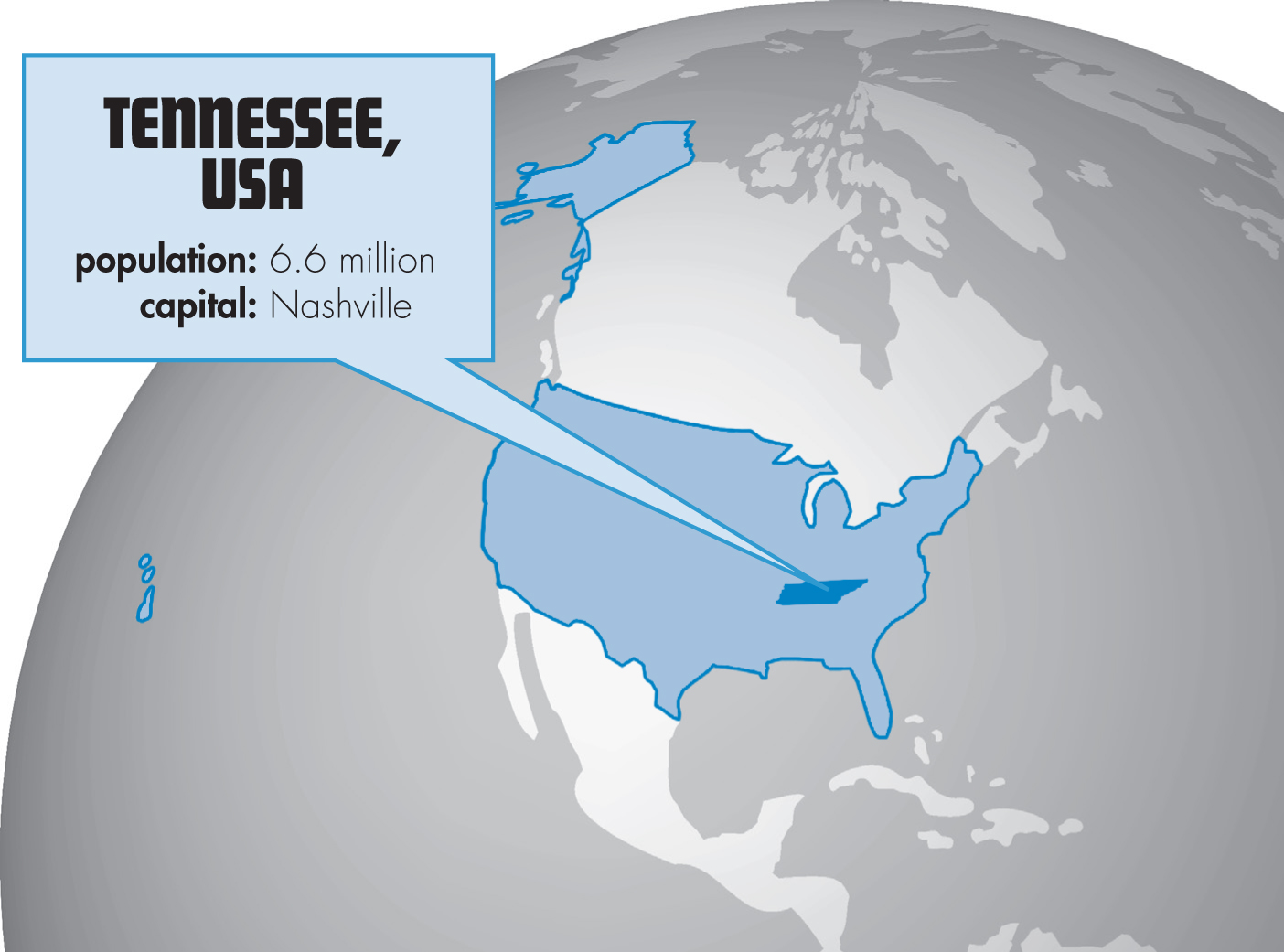

When Conner was eight and Cayden was six, Conner asked their mom if he could sign up himself and his brother for the Nashville Kids Triathlon near their hometown of White House, Tennessee. The boys’ mother, Jenny, was skeptical. In the kids’ triathlon, competitors would swim 100 yards, bike three miles, and run half a mile. Even with Conner’s help, it seemed impossible. Could the boys finish? Would Cayden enjoy it? But Conner and Cayden started training, and eventually their mother let them enter.

On the day of the race, Conner swam 100 yards, pulling Cayden in a small raft. Cayden wore a life jacket and smiled the whole time. When Conner came out of the water, a coach the family had met online helped lift Cayden from the raft into the bike trailer for the hilly, three-mile ride. Then Conner pushed Cayden in a stroller for the half-mile run.

An average kids’ triathlon competitor completes the course in about 19 minutes. It took Conner and Cayden 43 minutes and 10 seconds. They finished last. As they came across the finish line, Conner pumped his fist in the air. Cayden can’t speak with words, but his laughter said it all: For the Long boys, finishing last at a kids’ triathlon felt like winning the Kona Ironman World Championship.

“What Conner did for Cayden—that choice to do one little race on a weekend—changed them,” their mom told Sports Illustrated.

The boys continued to compete in more triathlons and fun runs. In the summer, they had a race most weekends. When Conner lined up with Cayden at the start, or after the boys crossed the finish line, people would congratulate the two, telling them how inspiring they were and wanting to have their picture taken with Conner and Cayden.

It was the exact opposite of how Conner saw people treat his brother on most days.

“One thing that makes me really mad is when people say the ‘R’ word . . . I just tell ’em that it doesn’t matter what he looks like on the outside, it’s a matter of what’s on the inside. He still has feelings and he understands what you say about him,” Conner told Sports Illustrated.

Through Conner’s kindness, Cayden was able to experience not just the worst of what people can be, but also the absolute best. In 2012, Sports Illustrated Kids named Conner and Cayden as SportsKids of the Year. At the award ceremony, basketball star LeBron James cried as he congratulated the brothers on their achievements.

For some kids, an award like that would be the finish line. But for Conner and Cayden, it was only the start. In 2014, 10-year-old Conner talked the company Miracle Recreation into building a special playground in White House, Tennessee, designed to be accessible to people in wheelchairs and with other challenges. Now, Conner and Cayden can play together. Cayden’s favorite part is a wheelchair-accessible swing called the Accelerator that he can sit in while Conner spins him around.

“As soon as we pull up [in the car], Cayden’s so excited, and he just loves it a lot,” Conner told reporters.

Triathlons, playgrounds, and more, Conner’s first goal is to play with his brother. His second goal is to show the world that his brother can play.

“Maybe people that didn’t care in the past will care in the future,” Conner says. If anyone can teach people to care, it’s Conner Long.

Story photo credit © KCLARKSPHOTOGRAPHY | DREAMSTIME.COM

People Don’t Know and I Don’t Blame Them

Hashmat Suddat

When Hashmat Suddat was young, he lived in a nice house with his parents, five sisters, and younger brother in Kabul, the capital city of Afghanistan. He went to school. One of his older sisters had just become a teacher.

“Everything was nice before the war,” he said.

Then the Taliban came. From 1996 until 2001, the Taliban ruled Afghanistan. The group ruled Afghanistan according to the law of Sharia, which was their interpretation of crime, politics, morality, and daily life written in the Muslim holy book, the Koran. The Taliban’s form of Sharia thought that women were meant to be born at home, work at home, and die at home. Hashmat’s older sister had to leave her job as a teacher. Hashmat’s parents spoke out against what they saw as unfairness during the Taliban rule.

And so his parents were killed.

At 17 years old, Hashmat became an orphan and a refugee. Afghanistan was a bad place for anyone with connections to the anti-Taliban movement, so Hashmat and his siblings decided to leave the country for what they hoped would be a better life in neighboring Pakistan. After a long journey, the family crossed the border into Pakistan to find a life that was nothing like the world they knew. There were no schools, and they had no home. Without parents to protect them and provide for them, Hashmat took whatever jobs he could find, trying to earn enough money to keep his family from having to live in the refugee camp. Hashmat and his family applied for programs that would help them resettle in a country where they could build new lives. Nine hard months later, Hashmat and his siblings were allowed to leave Pakistan to make a home in the United States.

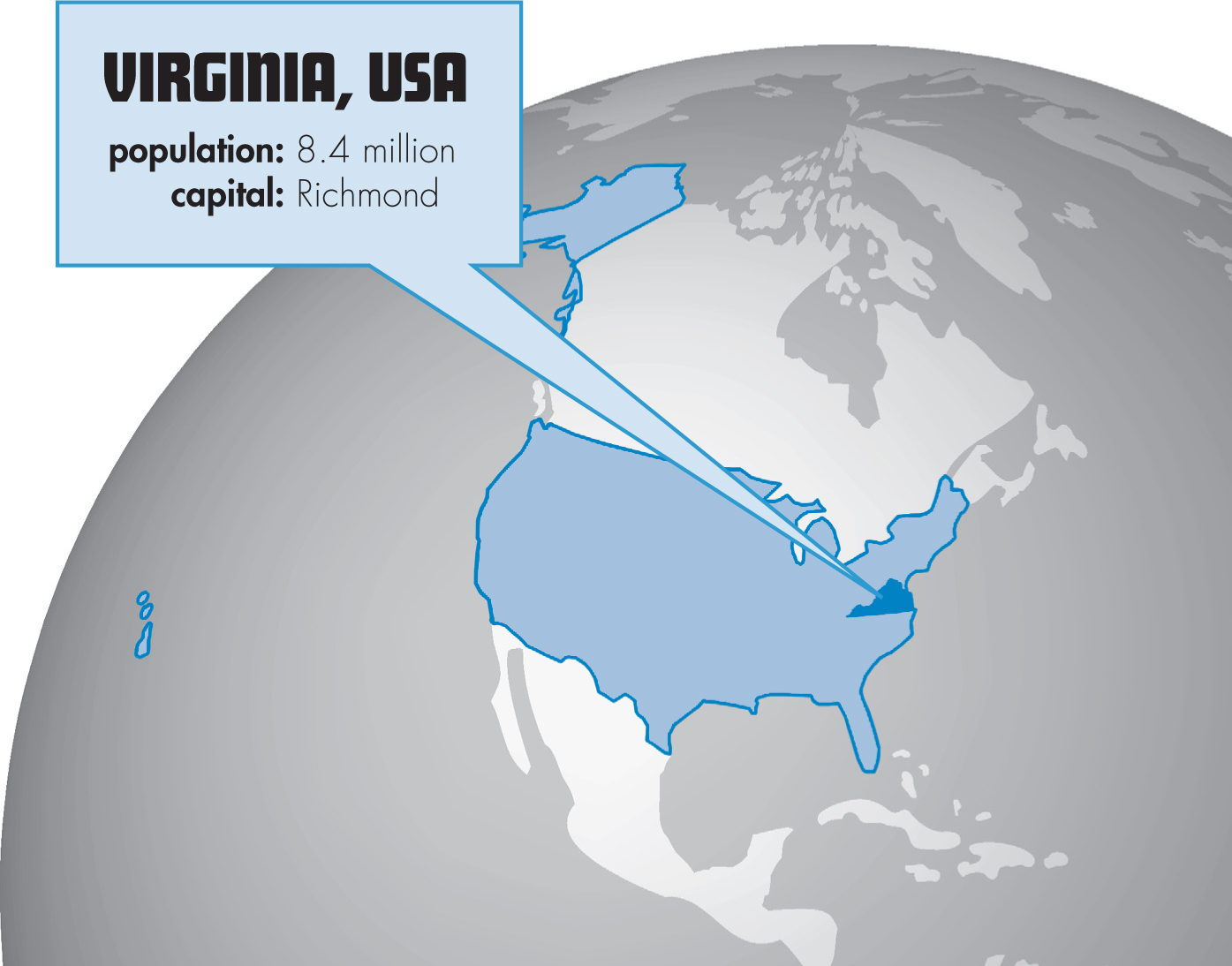

First, the Taliban had changed the family’s life in Afghanistan. Then, Hashmat and his siblings had spent almost a year living on what seemed like the face of the moon in Pakistan. And now, they found themselves in an apartment in Virginia.

“If someone had told me that I could look out the window, and as far as my eyes could see, one side of the road would be all white headlights and the other side would be all red lights moving at 60 miles per hour, I would have said they were exaggerating,” said Hashmat in an interview with the United Nations High Committee on Refugees (UNHCR).

The timing of their arrival meant the family traded one kind of challenge for another. They arrived in the United States just after the terrorist attacks of September 11, 2001. Hashmat and his family were refugees from Afghanistan, the country that protected Osama bin Laden, the terrorist who planned the September 11 attacks. Hashmat’s family has brown skin. They are Muslim. It was not an easy time for Muslim people with brown skin from Afghanistan in the United States, especially for a senior at a new high school.

“Because of September 11, I suffered a lot from the backlash. Students, people in the community thought that Muslims were killers. Terrorists. People didn’t want to shake hands with me. ‘You might have shaken bin Laden’s hand.’ I explained I was a civilian. Just an ordinary civilian,” Hashmat told the UNHCR.

Hashmat’s life had already been hard enough. He didn’t need kids in Richmond, Virginia, blaming him for terrorist attacks by the same villains who had killed his parents. Hashmat and his family had suffered for years at the hands of the Taliban. And now they were being blamed for the acts of the Taliban as if they supported terrorism.

Still, Hashmat says, “People don’t know and I don’t blame them.”

Hashmat did one of the kindest things that one person can do for another: He forgave the people who bullied him for his brown skin, his religion, and the country in which he was born. And he understood that the cure for intolerance is understanding. The people who bullied him were scared because they didn’t understand the difference between a refugee from the violence in Afghanistan and the people who were creating the violence in the first place.

Hashmat met fear and racism with kindness, and he tried to help these intolerant people understand. For example, he explained to the UNHCR that people in the United States probably knew more about Osama bin Laden than he did. “You had his picture on the TV. In Afghanistan, we didn’t have TV. Or power. When I came to the United States, I saw his picture, who bin Laden was for the first time. We didn’t want to be around him. That’s why we left,” he said.

Someday Hashmat wants to return to Afghanistan to offer the same kindness of forgiveness and education there. “There is less war in Afghanistan now,” he says. “But that does not mean peace. Peace means education.”

Story photo credit © ARTUSRJ | DREAMSTIME.COM

Turning Down Fame

Justice Miller

In the small town of Olivet, Michigan, middle school football player Justice Miller was in the right place at the right time to take credit for a heartwarming act of kindness that brought the community together. Justice, the team’s star wide receiver, was being interviewed by CBS News about a special play at last night’s game.

The team’s running back had been sprinting for the goal line with no defenders in sight. Then suddenly, he went down. The coaches and parents thought he’d tripped, but Justice and the rest of the team knew what really happened. They had been planning this moment for two weeks. On the next play, a new running back entered the game—95-pound Keith Orr, usually the team manager, who had a learning disability. Keith’s parents had signed him up for football that year hoping he would learn about teamwork. Hike! When the next play started, the quarterback handed Keith the ball, and then the team cleared his way into the end zone.

“Nothing can really explain getting a touchdown when you’ve never had one before,” Justice told CBS News.

Keith was an instant celebrity. And the boys on the Olivet Middle School football team had the opportunity to be celebrities, too. Someone just needed to step forward and take credit. But when CBS News asked Justice for an interview, he wrote back, “I think you should really be interviewing our running back. He is the one who took the knee and really made it possible.” In other words, wide receiver Justice chose to take a pass on the spotlight. He chose to give up the chance to be famous and turn down the opportunity for the entire country to think that he had been the hero behind this beautiful, heartfelt, kind play on the football field.

Scoring a touchdown with his team changed Keith Orr’s life. After the game, his coach told the local TV station, “Now the other players eat lunch with him. Now they talk to him in the halls. Keith has discovered there are things he can accomplish he didn’t know he was capable of. His mom is now more at ease, knowing that he has friends to last him through high school.”

This kindness changed Keith Orr, and it changed Justice Miller, too. Instead of taking credit for the famous play, Justice humbly admits, “I kind of went from being somebody that mostly cared about myself and my friends to caring about everyone and trying to make everyone’s day.”

Justice’s first kindness was being involved in Keith’s touchdown, even if it was only by keeping the plan secret and then helping to block for Keith’s run into the end zone. But his true kindness was and continues to be letting the moment be about Keith and not about himself.

Story photo credit © SSTEVENSON | DREAMSTIME.COM