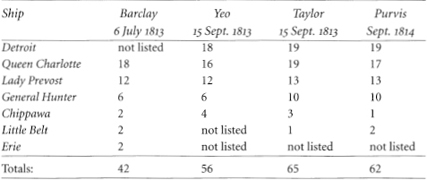

Battle participants present a varied list of armaments for the British squadron on Lake Erie (see Table 6). Robert H. Barclay’s list of 6 July 1813 undoubtedly contains an accurate description of naval armament at the time he operated out of Long Point with the Chippawa supporting General Procter’s second Fort Meigs expedition. Sir James L. Yeo probably based his list on information received after Barclay’s list, but not after Barclay redistributed weapons in late August. Yeo omits all of the schooners and sloops at Barclay’s disposal. Sailing Master W. V. Taylor of the Lawrence appears the more accurate, but he is two pieces over on the armament of the Queen Charlotte and may have reversed the numbers for the Chippawa and Little Belt. Lieutenant Francis Purvis’s testimony at the Barclay court-martial is the generally accepted figure for British guns on 10 September, except for the addition of one more gun on the Little Belt than he listed.1

Despite the discrepancies in the original documents regarding the armament of the British squadron, as early as 1817 Royal Navy historian William James noted the British had 63 guns, without specifying the number on each ship.2 Starting with Alexander Mackenzie’s 1843 biography of Perry, all historians allocate these 63 guns thus: 19 on the Detroit, 17 on Queen Charlotte, 13 on Lady Prevost, 10 on General Hunter, 3 on Little Belt, and 1 on Chippawa.3

British Armament as Listed in Contemporary Documents, 1813–14

Considerable discrepancy exists between documentary accounts and historians regarding the types and poundage of guns on each vessel. In the last few days before the battle, Barclay not only placed artillery from Fort Malden on the Detroit, but he also transferred artillery from one ship to another, increasing and redistributing his firepower. In general, historian Frederick Drake’s account is considered more authoritative, but we have no corroborative evidence of his allocation of the 24-pounder carronade on the Little Belt.

If one assumes the correctness of Barclay’s 6 July 1813 report of ship armament (see Table 7), one can make several suppositions regarding the Royal Navy squadron’s artillery in September. The two 8-inch field artillery howitzers on the Chippawa were removed for the traversing gun (whether it was a 12-pounder or a 9-pounder is in dispute). Queen Charlotte gave up four of her 24-pounder carronades in exchange for three 12-pounder long guns. A leading question is, what happened to the four 24-pounder carronades taken off the Queen Charlotte? At least one appears to have been put on the Detroit. Possibly Lieutenant Purvis was incorrect when he stated that one of the two carronades on that vessel was an 18-pounder. But there were two 18-pounder carronades on the General Hunter in July that were not there in September. Was one of them put on the Detroit? It would be most unusual for Barclay to have had two carronades of unequal capacity on his flagship if this could be avoided. Logically, the Detroit had either two 18-pounder or two 24-pounder carronades, but this does not appear to have been the case. This disparity would not have adversely affected the Detroit’s sailing characteristics. It appears that the Little Belt was unbalanced, however, with her three guns of different capacities.

We assume all the long guns for the Detroit, the three for Queen Charlotte, and the 2-and 4-pounders on General Hunter came from Fort Malden. Here again we confront a problem. Why remove two 6s from the General Hunter and replace them with 2s? Was Purvis incorrect in stating that there were two 6-pounders and four 4-pounders? Could he have reversed the two numbers?

Little Belt’s armament is the most difficult to ascertain. She may have retained the 12-pounder long gun and 12-pounder carronade she had in July and presumably received one more gun, if the total of 63 guns is correct. Purvis described her as having one 9-pounder and one 6-pounder long gun. Secondary sources differ. The Malcomsons argue that the Little Belt had one 9-pounder and two 6-pounders. Their source is Purvis, who gives her only one 6-pounder. One the other hand, Drake claims the vessel had the 12-pounder long gun and 24-pounder carronade she had in July, and adds another carronade. But if she had but one 24-pounder carronade, what happened to the two carronades from the Queen Charlotte? A 24-pounder carronade would certainly press the envelope of vessel capacity. Its recoil would have greatly stressed its upper-works. Did Barclay deliberately deceive the court-martial regarding his weight of metal through Purvis’s testimony? Was Purvis correct in stating there were only 62 guns?

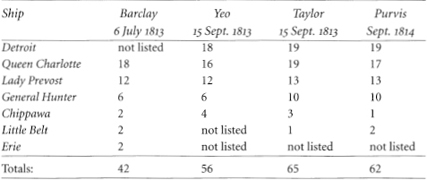

British Gun Lists, 1813–1991

A partial solution to the armament problem revolves around the three vessels Barclay left behind in Amherstburg—the Ellen, Erie, and Nancy. Assuming the Erie kept the guns Barclay reported she had in July, we know that the Nancy had one long 6-pounder and two 24-pounder carronades. This accounts for the missing carronades from the Queen Charlotte and one of the long guns from General Hunter, and makes Purvis’s list appear more logical. No evidence of her armament has been found.4 But the peculiarity of the Nancy’s armament makes Drake’s discussion of the carronades on the Little Belt more in keeping with Barclay’s designs. Were this not enough, in 1826, William James wrote another account of the battle of Lake Erie that gives a totally different list of British artillery capabilities at variance with Purvis and all subsequent accounts.5

Given conflicting data, it is difficult to reconstruct definitively the number of guns and the total and broadside weights of metal for the Royal Navy squadron. Drake’s conclusions are close, and we use them for the computations in the text.