The sea with ships, the fields with armies spread,

The victor’s rage, the dying, and the dead.

Thus while the morning-beams, increasing bright,

O’er heaven’s pure azure spread the glowing light,

Commutual death the fate of war confounds,

Each adverse battle gored with equal wounds.

The Iliad

ON FRIDAY MORNING, 10 September 1813, the sun “rose in all his glory,” remembered American seaman David Bunnell, “but before it set, many a brave tar on both sides was doomed to a watery grave, and many a jovial soul who had ‘led the merry dance on the light fantastic toe,’ the evening previous, never danced again—unless indeed we have our frolics after death.”1 While the Americans frolicked, the British sailed down the Detroit River and out into Lake Erie.

Up until that morning, Commander Robert H. Barclay’s attempts to maintain British command of Lake Erie had been frustrated by two incidents of “Perry’s luck.” The first occurred in mid-June when the American commodore was able to elude Barclay’s attempts to engage the Black Rock squadron during its journey from the headwaters of the Niagara River to Presque Isle Bay. The second was when Barclay’s unexplained absence off Presque Isle Bay in early August resulted in the Americans being able to haul their brigs over the bar and onto the lake before the British commander returned. As dawn arose on the tenth, however, the situation seemed to portend a reversal of British fortunes. A gentle breeze was blowing from the southwest; Barclay held the weather gauge. If he retained the wind advantage, he could feasibly inflict considerable damage upon the American squadron or even defeat it from long range, thus avoiding Oliver Hazard Perry’s carronades. It could not be lowered in surrender. In anticipation of victory, Barclay shipped aboard the Detroit a huge bear that the British planned to slaughter and feast upon in celebration of their triumph.2 Surely “Perry’s luck” would not rise to the fore a third time.

As the blanket of darkness was thrown from the surface of Lake Erie, the cry “Sail ho!” bellowed from the maintop of the American flagship. Dulany Forrest, the Lawrence’s second lieutenant and officer of the watch, echoed back, “Where away?” “Off [Rattle]Snake Island,” came the reply. Forrest scurried below to inform the commodore. Perry soon bounded on deck, and immediately signal flags were hoisted instructing all vessels to get under way. The shrill pipes of the boatswains’ mates aroused the excited crews and the word passed, “All hands up anchor.”3

The exact order of sailing when the American flotilla exited Put-in-Bay is not known; probably the Niagara was the leading brig, in accordance with Perry’s expectation that the Detroit would follow the Queen Charlotte in the British line of battle. By 0700 the American squadron had cleared its anchorage and the entire British squadron was in sight. Though Perry was not yet close enough to ascertain details, he now knew what he was up against, and he was cognizant of his flotilla’s limitations. If the Americans were to make effective use of their superior firepower, they needed to seize the weather gauge. The British fleet was well to windward of the Americans, so to attain the wind advantage Perry must first clear Rattlesnake Island and then headreach to the west of Barclay’s position. To weather (sail to the windward side of) Rattlesnake Island, Perry must set a westerly course, but with the wind blowing from the southwest at approximately seven knots, the Americans would have to sail directly into the teeth of the wind, a nearly impossible task.4

If he opted to fight without the weather gauge, Perry would subject his squadron to an unfavorable battle position. Although the American fleet maintained a three-to-two advantage in long-gun weight-of-metal, the British long-gun numerical superiority of thirty-five to fifteen would come into play. If Perry were foolish enough to engage against such odds without the wind, then Barclay could stand out of carronade range, isolate Perry’s vessels—particularly the brigs, armed almost entirely with carronades—and then defeat the American squadron in detail. With either of his enemy’s brigs disabled (one lucky shot could bring down a mast), Barclay’s chances of victory would increase dramatically.

Route of Flagships, 10 September 1813

from the 1994 estimates of Captain Walter B. Rybka, master of brig Niagara, Erie, Pa.

Perry’s only hope was to tack back and forth, claw into the wind, and hope that he could headreach on the enemy fleet. Sailing close-hauled with the wind three points forward of the beam, yards braced nearly to the point of shivering, the brigs laboriously cut across the wind, first on the larboard tack heading toward Rattlesnake Island, then on the starboard tack toward South Bass Island’s western shore. Shouted orders resonated across the placid waters: “Man the braces,” “Helm alee,” “Mainsail haul,” “Let go and haul.” Under the watchful eyes of officers, guided by petty officers and assisted by experienced seamen, confused landsmen and soldiers heaved at the rough hemp braces. Men tripped and fell over each other, across gun tackle, and atop bundles of line piled beneath the pinrails, stumbled about in muddle, and smashed into other sweaty bodies in the cramped and unfamiliar closeness of the crowded gun deck. Blisters formed on hands rubbed raw and bloody by coarse line as perspiration poured from straining bodies, giving the word pain a new definition as the salty sweat seeped into broken blisters. Almost to the point of exhaustion, the men hauled the cumbersome yards, first to larboard, then to starboard, sweating lines to keep the sails taut and to squeeze every ounce of advantage from the wind. Over and over, back and forth, hour after hour, the American squadron scratched for every knot of speed and every yard of headway.

Nothing seemed to work. The keels of the large brigs could not bite deeply enough to prevent the shallow-draft vessels from making leeway. Perry glared in frustration as his brigs slid sideways with the wind, negating what little headway he managed to make. The smaller vessels, with their fore-and-aft rigs, could headreach into the wind much more easily. These gunboats, virtually useless without their larger consorts, were forced to hold back. After all the hard work, the coordination, the vexation, and the external and internal stresses, Perry now faced the prospect of being stopped by, of all things, a foul breeze.

Shortly before 1000, after nearly three hours of wasted effort, Perry finally conceded. Weathering Rattlesnake Island was clearly impossible, as was any hope of grasping the weather gauge, so Perry decided to change course and proceed to the eastward of Rattlesnake Island. The commodore consulted with his sailing master, William V. Taylor, before making the decision. Then he instructed Taylor to wear ship and run down to leeward of the island. Taylor responded that such a maneuver would force the Americans to engage at a tactical disadvantage by losing the weather gauge. Perry replied, “I don’t care, to windward or to leeward, they shall fight to-day!”5

Perry was a fighting sailor; he was determined to engage the British. This contrasted starkly with Commodore Isaac Chauncey’s conduct on Lake Ontario, where the American commodore refused to be drawn into any engagement where there might be the slightest tactical liability. On the other hand, Perry felt compelled to take some type of action or else he might find himself trapped in the midst of the Bass Islands with his vessels masking each other’s fire and his ships scattered in disorder. Certainly Barclay hoped for such an American predicament.

However, before the order to change course could be executed by Taylor, the wind hesitated, died, then suddenly backed 90 degrees and blew lightly from the southeast. Just moments before, Perry was angry, frustrated, and prepared to fight at a disadvantage; now the wind blew from an ideal direction for the Americans. Perry’s unbelievable luck changed for a third time in this campaign. Barclay could only observe the situation in dismay; the gods seemed against him. Often described as a miraculous turn of events for the Americans, wind shifts of this nature are actually a common phenomenon on western Lake Erie that time of the year.

The sinking feeling that must have coursed through Barclay’s chest served only to emphasize a rapidly deteriorating state of affairs. Barclay had just lost his one great advantage, but he was not about to submit. With a little ingenuity and a modicum of good fortune the battle could still be won. Although the breeze favored the Americans, it was barely strong enough to propel a ship through the water. Perry’s approach would thus be exceedingly prolonged, and a slow approach would allow time for Barclay’s more numerous long guns to fire upon the American ships virtually unchallenged. If Barclay could dismast or disable one or both of the American brigs before Perry’s deadly carronades floated into range, the day could yet belong to the British.

What would Perry’s actions have been if the wind had not shifted? This is one of the battle’s fascinating “what-ifs.” It has always been assumed, and correctly so, that Perry intended to fight regardless of any British advantage. Had Perry maneuvered leeward of Rattlesnake Island, Barclay presumably would have retained the weather gauge. Such a script was more than likely, but not a certainty. The British might make a basic sailing error that could pass the weather gauge to Perry. A number of scenarios were possible depending upon which direction and on which tack the opposing squadrons maneuvered. While most of the variables favored the British, Perry had a powerful and reliable ally on his side—time.

Barclay had to fight; Perry did not. If Perry had remained patient and bided his time, he conceivably could have set a southeasterly course, placed his squadron against the south shore of the lake in a position of advantage, and simply waited. Having no choice but to engage, Barclay would have to yield to Perry’s chosen position. Rather than sail out of the harbor in the first place, Perry might have employed the same tactic that Master Commandant Thomas Macdonough used a year later at Plattsburg Bay, New York—remain in harbor, place his vessels to a tactical advantage, rig spring lines to turn his anchored vessels, and force the British to attack him. Either way, the key would have been for Perry to remain patient, but with the Rhode Islander’s penchant for impetuosity, such a course of inaction seems unlikely. Perry wanted to fight at the earliest possible opportunity, just like his friend James Lawrence of the Chesapeake. Thus Perry placed his vessels at potentially needless disadvantage and hazarded the entire campaign in the Old Northwest in a lust for naval glory. Fortunately for the United States, Perry was not placed in a position to test his patience or his judgment. The wind was at his coattails; Neptune smiled on the young American. He now had the advantage he so desperately desired.

When the wind shifted, Perry altered course, bore up, and cleared Rattlesnake Island to the windward at 1000. Having no options, Barclay was forced to deviate from his intended plan of action. The British commander eased to a westerly course on the larboard tack and hove to in order to await the American squadron. The two fleets approached one another at an angle of 15 degrees, sailing west by north. The British battle line, about eight miles distant, was clearly revealed to Perry for the first time—”Two ships,—Two Brigs;—one Schooner and one Sloop.”6

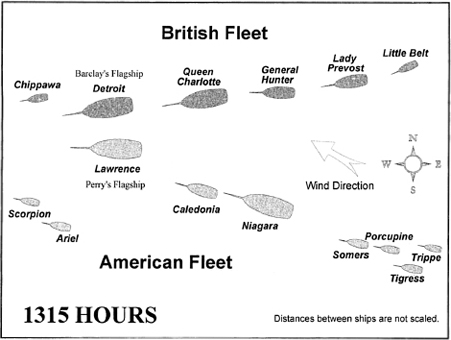

Perry was still uncertain about the individual British vessel alignment. The commodore signaled the Niagara to heave to, after which the Lawrence hauled alongside. Perry conversed through his speaking trumpet with Captain Brevoort, whose previous experiences on the lake made him familiar with all the vessels in the Royal Navy squadron. Brevoort apprized his commodore about the various British ships. Assimilating Brevoort’s insights, Perry discovered that he had erred in his estimation of Barclay’s battle formation. Instead of the Queen Charlotte leading the Detroit, Barclay had posted his flagship in front of his second-largest vessel. The British line was arrayed with the Chippawa in the van, followed by the Detroit, General Hunter, Queen Charlotte, Lady Prevost, and Little Belt.7

At this point Perry reorganized his line of battle, placing the Ariel and Scorpion off his weather bow and realigning the Caledonia, Niagara, Somers, Porcupine, Tigress, and Trippe to follow the Lawrence, in that order. Undoubtedly, Jesse Elliott was disappointed. Originally the Niagara was designated to the American van, a place of honor, but Elliott watched in dismay as his ship not only lost that opportunity but also the serendipitous chance to engage the enemy’s flagship. Even though he knew Perry would in all probability make the necessary adjustments to ensure that the Lawrence would face the Detroit, Elliott nonetheless must have felt pangs of regret while watching the Lawrence and probably the Caledonia glide past, leaving his brig astern. Whether or not this change in position affected Elliott’s subsequent conduct remains a matter of speculation.

Perry’s alteration of his formation may be criticized on two grounds. First, he reduced his ability to direct the battle from the center. Because of the angle at which the Americans approached the British line, the Lawrence would be in the fight before any of the trailing vessels. Perry could become so involved in fighting the Lawrence’s portion at the head of the engagement that he would fail to direct his whole squadron as effectively as he might have from the center. Moreover, by placing the slow-sailing Caledonia between his two brigs, Perry slightly reduced his ability to control the Niagara and the latter’s ability to closely follow the flagship if the Caledonia lagged behind. At this critical juncture, Perry placed an extraordinary amount of responsibility in his subordinates’ abilities to carry out his less than fully articulated battle plans while he plunged into the heat of the fight. This new tactical arrangement did conform to Perry’s directive for the Caledonia to engage the General Hunter. Whatever the criticism and justification of this formation, Perry allowed Barclay’s alignment to dictate that of the American squadron.

As the ships prepared for action, men in both squadrons scampered in disciplined chaos back and forth across crammed decks. Cannon implements were laid out carefully, tompions were removed from muzzles, gun tackle was unshipped and flaked down, and the various projectiles were checked closely. American sailors lit slow match and carefully laid it in tubs of sand near the guns. It was only then the gun captains on the Detroit discovered they had no slow match for touching off the big guns. The British apparently had not employed live fire training on their newly launched flagship, and the slow match deficiency was not discovered until it was too late to make new slow match or acquire a functional replacement. (Since slow match is not difficult to manufacture, if the British had been aware of the defective match before they sailed, it would have been a simple process to make new, effective match.) Barclay’s gun captains were thus reduced to the desperate measure of loading and firing pistols into the vents of their cannons in order to make them fire.

On the ships of both sides, powder monkeys hurried below to fill their cylindrical leather pouches with prepared cartridges. Decks were sanded to provide secure footing and to soak up blood. Buckets of water were placed near each gun to quench the raging thirst of sailors in battle and to extinguish fires. Beneath each gun muzzle was another bucket of water into which the sponger plunged his sponger/rammer before swabbing the gun barrels. Caches of cutlasses, pikes, and boarding axes were readied for instant use, either to board or to repel boarders.

Marines and soldiers ensured that flints were securely fixed on their musket locks and that cartridge boxes were full. Some marines and soldiers slung their muskets and climbed the ratlines to the fighting tops of the larger vessels, while the remainder formed miniature lines of battle on the decks. The small boats from each vessel were lowered and towed astern so they would not be damaged during the battle or explode into deadly splinters and add to the carnage on the deck. All loose gear was fastened, secured, or stowed below. After ten or fifteen minutes the ships were cleared for action and the bustle subsided; now came the wait.8

About 1100 Commodore Perry stepped forward and climbed upon a carronade carriage midships on the Lawrence’s larboard side. In his arms he carried a large navy blue banner upon which was emblazoned in crude white letters “Don’t Give Up the Ship.” “My brave lads,” he said, “this flag contains the last words of the brave Captain Lawrence. Shall I hoist it?” “Aye, Aye,” they said, and gave three cheers. As the motto flag went up, Perry shouted to the crew: “My Good Fellows it is not to be hauled down again.”9

Although often attributed to Perry himself, this phrase was actually the dying utterance of Perry’s friend Captain James Lawrence of the U.S. Frigate Chesapeake. On 1 June 1813 his ship dueled the British frigate Shannon off Cape Ann, Massachusetts. Mortally wounded early in the engagement and carried below decks, Lawrence was informed his ship was lost and, according to one version, angrily retorted: “Keep the guns going and fight the ship til she sinks. . . . Don’t give up the ship. Blow her up.” Ironically, Lawrence’s men did surrender, and in record time, but even so, Perry’s flagship was named in honor of his dead friend and Lawrence’s last words were employed as Perry’s battle slogan. The words were hardly inspiring, having a negative connotation, but if nothing else they clearly indicated Perry’s determination to do his utmost in the coming engagement.10

Each man received a ration of grog, and the midday meal was served early. The drums and fifes struck up “All Hands, All Hands, To Quarters,” and each man went to his respective station. Perry strolled leisurely around the vessel, inspecting each gun in his battery, exhorting the various crew members. To the veterans of the U.S. Frigate Constitution he asked, “Well, boys are you ready?” The reply was a hearty “All ready, sir!” “I need not say anything to you,” Perry noted in passing, “You know how to beat those fellows.” Then he came to a gun crew manned by his native Rhode Islanders: “Ah! Here are the Newport boys, they will do their duty I warrant.” Thus he sought to soothe everyone’s nervousness by inspecting each gun, questioning each gun captain, and encouraging each crew member.11

For the crewmen it was an agonizing wait. Seaman David Bunnell recalled it graphically:

There being only a light wind, we neared the enemy very slowly, which gave us a little time for reflection. Such a scene as this, creates in one’s mind feelings not easily described. The word “silence” was not given—we stood in awful impatience—not a word was spoken—not a sound heard, except now and then an order to trim a sail, and the boatswain’s shrill whistle. It seemed like the awful silence that precedes an earthquake. This was the time to try the stoutest heart. My pulse beat quick—all nature seemed wrapped in awful suspense—the dart of death hung as it were trembling by a single hair, and no one knew on whose head it would fall.12

A number of officers, fearing what lay ahead, took the opportunity to ask friends to look after their affairs. Perry hastily reviewed his wife’s letters. These and his official dispatches were put into a lead-lined bag that he gave to Dr. Parsons, ordering him to throw the weighted pouch overboard should the worst happen. “This is the most important day of my life,” he told Purser Samuel Hambleton. Several other officers also approached Hambleton. Marine lieutenant John Brooks requested the purser tend to his affairs should he fall. Another “excellent officer,” possibly Sailing Master Taylor, requested that, were he to be killed, Hambleton and Perry should “endeavour to get something done for his wife and children.”13

The sailors had no such final-minute tasks; only their imaginations could fill the void. Every sailor who had ever been in a close quarters engagement knew what to expect, and those who had not could vividly imagine the carnage that awaited. They were aware that a naval fight embodied more terror than a land battle ever could. It was not just cannonballs they feared, though these were bad enough. They were afraid of splinters, because when a cannonball plowed into the side of a wooden ship, showers of wood splinters, anywhere from the size of a fingernail to that of a boarding pike, scoured the decks. They were afraid of grape shot, canister, chain shot, bar shot, langridge, and anything else that could belch from the muzzle of a smoothbore cannon. They were afraid of being raked, where a single artillery round carried death the entire length of an open-decked ship. They were afraid of the marksmen on the enemy ships, their long-barreled muskets belching one-ounce lead balls. They were afraid of being boarded, of the personal bloodletting and mutilation perpetrated with pistol, cutlass, musket, bayonet, boarding ax, pike, dirk, belaying pin, sponge rammer, handspike, and even the hands and feet if necessary. They were afraid of muzzle flashes or sparks igniting dry wood or canvas, fire always being the sailor’s nemesis. They were afraid of being forced into the water, most sailors never having learned how to swim. But most of all they were terrified of being wounded and having to face the dank horror of the orlop deck, where the surgeon waited in his butcher’s apron with probes, lancets, scalpels, and bone saws, with the only anesthetic a shot of whiskey and a thick leather strap on which to bite. There was no place to hide, nowhere to run. At the hatches leading below the main deck the various captains posted marines to force any fleeing members of the crew to do their duty, and perhaps send them to their death.

The light airs, slowing the fleets’ approach to one another, produced another negative effect for Perry. The square-riggers were better sailers in this type of breeze. The three small schooners and one sloop bringing up the American rear started to lag. The Somers, one of the converted merchant vessels from Black Rock, was more cumbersome than the Erie-built schooners that followed her, and she was unable to keep station with the ships ahead. The vessels astern of the Somers maintained their positions in line, as per orders, even though this meant they also would falter. Even with their sweeps working, the trailing vessels were unable to hold station. While the five leading ships had managed to maintain a cohesive line, by 1130 the Trippe, Perry’s aftmost vessel, had fallen nearly two miles behind.14

By impulsively bearing down on the British line, allowing the schooners to lag farther and farther behind, Perry once again exhibited his reckless impatience. It was true that these four vessels carried only five guns among them, and it was also true that Perry need only get his two largest ships in close action against the two largest British vessels to attain the firepower superiority he deemed necessary to win. Perry did not really need these vessels; the schooners and sloop were not all that important. Or were they? Perry was surely aware that because of the light airs his slow approach to the British line would allow Barclay to bring his more numerous long guns into play well before the Americans closed to within carronade range. One shot from a British long gun could dismast either of Perry’s brigs and put her out of action. Perry needed all the support and whatever diversion he could muster. Of the five cannons on the four trailing vessels, three were long 32-pounders and one a long 24-pounder; each could reach the British from over a mile. Since Barclay had to fight, Perry need not worry that the British would try to avoid battle, as Yeo sometimes had done on Lake Ontario.

Perry did not need to rush into battle without his long guns. His trailing gunships, somewhat overloaded with their heavy armament, could labor in a moderate sea and under such circumstances would be much less accurate in their gunnery. Continuing Perry’s good luck, on this day these smaller vessels faced a relatively calm lake, thus maximizing their capacity to fire accurately at their foes. Because of his unyielding urge to engage as quickly as possible, Perry left astern 40 percent of his long-gun broadside capability. A prudent commander would utilize all available firepower.

Some among Perry’s contemporaries argued that “an officer seldom went into action worse, or got out of it better.” But James Fenimore Cooper, generally considered one of Perry’s critics, argued that Perry’s “line of battle was highly judicious” and that by “steering for the head of the enemy’s line” Perry prevented Barclay from “gaining the wind by tacking.” Cooper concluded that “the American commander appears to have laid his plan with skill and judgment, and, in all in which it was frustrated, it would seem to have been the effect of accident”—the light winds.15

At 1145 a band on board the Detroit began playing “Rule Britannia.” British seamen cheered up and down the line. Then a bugle sounded on the Detroit, followed immediately by the crash of a 24-pounder, a ranging shot that splashed harmlessly near the Lawrence. About five minutes later a second 24-pounder sounded, but this time Perry’s flagship received her first hit and flying splinters killed and wounded American sailors. With the Lawrence’s carronades still out of range, Perry ordered the Scorpion to open fire with her long 32-pounder, and the Ariel responded with her four long 12-pounders; the Lawrence also added her long 12-pounder bow chaser to this opening exchange. The battle for the control of Lake Erie had, at long last, begun.

When the battle opened, the Lawrence’s position was approximately six nautical miles southeast of tiny West Sister Island, and the Detroit was about five nautical miles due east of the same islet. The flagships were more than one nautical mile apart.16 The two sides found themselves in a light wind and smooth water as the Americans gradually sailed toward their foes at about a 15-degree angle. The American line was strung out and the British were bunched closely together. Coincidentally with the cannons’ roar, Perry hoisted a signal for all vessels to engage their opponents in the order previously designated.17

For the next half hour the American van withstood the British fire without being able to inflict significant damage upon their opponents. In frustration, or in an attempt to take his crew’s mind off the punishment, Perry luffed18 (turned parallel to the enemy line) the Lawrence and loosed a broadside, the balls splashing well short of the British line. When a second broadside brought similar results, there was nothing Perry could do except turn and bear down on his foes until his carronades could take effect.

Before the Lawrence’s first broadside hit the Detroit, Perry’s impetuosity was playing into Barclay’s hands. British long guns were damaging the Lawrence, Ariel and Scorpion, and the majority of the American squadron trailed behind. Half the American long guns were out of range of their Royal Navy counterparts, and the second American brig slipped farther and farther behind the Yankee flagship. If Barclay could dismast or disable the Lawrence before the mass of American firepower could be brought to bear, the day could yet belong to the British, despite the odds arrayed against them.

The Battle of Lake Erie at 1215 hours

But this did not happen. Whatever one might say about the nonfiring drill Barclay had put his gun crews through over the previous month, their lack of long-range target practice began to tell. Because the Lawrence sailed almost directly toward the Detroit, Barclay’s gunners had less of a target than if the two ships had been on more parallel tacks. Despite half an hour of almost uncontested firing at her, no masts or spars fell to the Lawrence’s deck. Perry’s luck held again. His ship had been hurt, but not mortally, and all her guns were still in action.

Finally, at 1215 the Lawrence eased into range. Perry luffed his flagship once again and ordered his heavy 32-pounder carronades to open fire. Thus began an exchange that would last for more than two hours. When one considers that the typical engagement between wooden sailing warships lasted considerably less than one hour, the extent of time the two flotillas engaged is extraordinary. From below the main deck, Dr. Parsons thought “the dogs of war were let loose from their leash, and it seemed as though heaven and earth were at loggerheads.”19

An exchange of broadsides of extraordinary intensity ensued at the head of the two lines of battle. Perry told his crewmen, “Take good aim my boys, don’t waste your shot.” “Stand by,” said the commodore, and then he ordered, “Fire.” In that first broadside every carronade fired almost simultaneously. Inevitably, the broadsides became more and more ragged. Training and discipline began to tell among the more experienced gun crews, who loaded and fired faster than their less effective shipmates. Before long the officers dispensed with any attempt at maintaining regular broadsides. The Detroit and Lawrence closed to within point-blank range (around 330 yards for the 32-pounder carronades). The gun captains did not have to aim, they just fired level. Despite the dense smoke that made it impossible to see their opponent, it was difficult to miss. The small long guns from the Ariel and Scorpion fired on their opponents, but the British van concentrated all their fire on the American flagship.

The carnage on board the Lawrence was incredible. In a brief interlude, Seaman David Bunnell looked around: “Such a sight at any other time would have made me shudder, but now in the height of action, I only thought to say to myself ‘poor souls!’ The deck was in a shocking predicament. Death had been very busy. It was one continued gore of blood and carnage—the dead and dying were strewed in every direction over it for it was impossible to take the wounded below as fast as they fell.”20 Next to Bunnell a shot struck a sailor in the head, splattering the poor sailor’s brains so thickly into Bunnell’s face that he was blinded for a time. Momentarily, Bunnell was uncertain whether it was his shipmate or himself who was killed. Another crewman had both legs shot off and a number of spikes from the bulwark driven into his body. (He lived long enough to learn that the Americans had won, exclaiming “I die in peace,” and expired.)

Marine lieutenant Brooks paced the quarterdeck near Perry when a cannonball shattered his hip and thigh. In terrible pain, he pleaded with Perry and others to put him out of his misery—no one would do it. Brooks was eventually carried below, where after an hour of intense agony, he died. Grape shot hit Boatswain’s Mate William Johnson in the chest, fractured three ribs on his left side, and apparently nicked a lung. A wood splinter pierced marine private David Christie’s shoulder, penetrating almost to his hip joint. A falling backstay block bashed another marine private, Samuel Garwood, on the back of the head; he fell to the deck, blood gushing from his ears. Comrades carried Seaman Andrew Mattison below with a badly fractured leg. Carpenter’s Mate George Cornell crumpled to the deck after being struck above his left temporal bone. Seaman James W. Miles (who had enlisted under the name of James Moses) and Quartermaster’s Mate Francis Mason both suffered compound fractures of their arms. So mangled was Miles’s left arm that Surgeon Parsons amputated it. Amputation was one of the more common operations available to surgeons of the period, and Usher Parsons later recounted that “during the action I cut off 6 legs . . . which were nearly divided by cannon balls.” Among the six victims were Seamen William Thompson and George Varnum.

The Battle of Lake Erie at 1315 hours

Due to a shortage of experienced officers, Perry appointed Purser Samuel Hambleton to oversee a section of the Lawrence’s carronades. While observing his charges, a piece of rigging falling from aloft slammed Hambleton to the deck, breaking his left shoulder blade, tearing the clothes from his back, and bruising him dreadfully. Yet he continued to direct his section through the remainder of the battle. Struck on the head by shrapnel, Quartermaster’s Mate John Newen was carried below to the surgeon, where he eventually underwent the agonizing procedure of having his skull trepanned (a procedure wherein a corkscrew-like instrument removes a circular section of bone from the skull in order to relieve pressure and to provide an avenue for removing foreign objects from the brain). During the procedure, Surgeon Parsons extracted “several pieces of bone from the cerebrum and a piece of leather hat” that had been shoved into the pathetic seaman’s skull by the jagged metal.21

Whatever comfort the wounded might have hoped for, the situation below was little better than what they just left. Normally the sick bay or operating area in a ship of war was located below the waterline to protect the wounded, but the Lawrence was a shallow-draft vessel designed for fighting on the lake. Consequently, her wardroom—just below the main deck and above the waterline—had to be utilized. With the Lawrence’s surgeon disabled from fever, Dr. Parsons coped alone, with six helpers detailed to carry the wounded below or to restrain them during surgery. From his vantage point, Parsons heard “the deafening thunders of our broadsides, the crash of balls dashing through our timbers, and the shrieks of the wounded.”22

Parsons was so overwhelmed in the number of casualties that he had little time to operate. Instead he devised a simple form of triage, focusing his efforts on basic techniques like stopping bleeding and splinting fractured limbs. Even as he worked feverishly to save lives, cannonballs crashed through the bulkhead of the wardroom, one passing only a few inches over his head. At one point Parsons just had finished fixing a splint on the badly broken arm of Midshipman Henry Laub, and Parsons still had his hand on Laub’s arm when a ball burst through the starboard bulkhead and hurled Laub to the deck, a shapeless bloody bundle. Seaman Charles Pohig, a Narragansett Indian, had received similar ministrations from Parsons when another ball smashed through the wardroom, putting an end to Pohig’s already tortured existence.

Some grim humor did enter onto the scene. First Lieutenant John Yarnall’s face and head were covered with blood from a severe scalp wound. After a cannonball struck the hammock nettings, shredded bits of flag bunting and pieces of cattails stuck to Yarnall’s face. When he went below, some of the wounded found the grotesque sight of the lieutenant’s bloodied and splotched head humorous, laughing and shouting that the devil had finally come to get them.

As Parson’s surgery jammed up, he suddenly heard his name called. Moving to the skylight, he saw Perry on the deck above. With gun crews depleted, Perry requested Parsons to send one of his helpers on deck to assist the gun crews. Repeatedly this scenario was played out until all six of Parsons’s assistants had departed. Finally, Perry asked if any of the sick or slightly wounded were capable of helping. Those who were able crawled on deck to do what little they could. One of these, Carpenter’s Mate Wilson Mays, volunteered to help man the pumps, where he was later found with a sharpshooter’s musket ball in his heart.23

The animals on board also suffered. A pot of peas slated for the evening meal spilled onto the lower deck forward and sloshed over the planking. Scurrying about trying to lap up the peas was a pig that had escaped from the ship’s paddock. Lending a macabre and surreal quality to the scene was the fact that both of its hind legs had been shot off. Mindless of the pain, the pig pursued the peas across the deck, lapping them up. Perry’s dog was wounded and ran howling “in a most dreadful manner” from one end of the cabin to the other.

The Lawrence herself suffered the same carnage and indignities as did her crewmen and animals. After only fifteen minutes of combat, Sailing Master William Taylor recorded in the ship’s log that “our braces, bowlines, sheets, and in fact, almost every strand of rigging” was cut off. British shot cut the masts and spars, and rigging was severed in various places. A dwindling number of unwounded seamen scampered along the yards and through the rigging, attempting to make hasty repairs or reeve new lines where possible. One old tar discovered that one of the main stays was partially shot away and began fixing a stopper to the stay when another shot cut the stay away below him, sending the “stopperman” crashing into the mainmast. Seaman Bunnell recorded the angry sailor saying, “Damn you, if you must have it, take it.” Probably the language was quite a bit stronger.

As Barclay continued to concentrate his guns on the Lawrence, the Royal Navy artillery gradually reduced the American ship’s firing capacity. One British shot struck the muzzle of a heavy carronade, causing the hot iron tube to shatter and sending small pieces of metal in every direction, wounding an entire gun crew. “One man was filled full of little pieces of cast iron, from his knees to his chin, some not bigger than the head of a pin, and none larger than a buck shot.” Not only were guns damaged by enemy fire, they became inoperable by prolonged, excessive firing.

Early in the engagement the Americans had a tendency to use insufficient powder charges in their big carronades, which resulted in many of the Lawrence’s shots failing to penetrate the sturdy British bulwarks. Eventually the American gunners compensated, but occasionally with tragic results. Bunnell’s overcharged carronade jumped off its slide and could no longer function. By that time five of his eight gunners were either killed or wounded. Undeterred, Bunnell went to the next piece, which had but a single gunner remaining, and began operating it. Running out of projectiles, Bunnell improvised. Finding a crowbar lying nearby, the intrepid seaman jammed the awkward tool into the smoothbore cannon and sent it flying into the Detroit’s main rigging, severing three shrouds. Another time he crammed a small swivel gun into the wide-mouthed carronade and sent it sailing toward the British flagship. (Reputedly Barclay claimed afterwards that the Americans “did not fight like men, but like tigers,” and that they defied the laws of nations by firing such ungentlemanly projectiles. To which Perry reportedly replied: “What can you expect from a nation young in military tactics,—my men are all raw Yankees, and fire very carelessly—they do not care who they hit.”)24

One by one the guns of the Lawrence were knocked out, dismounted, or rendered useless. Finally, only one carronade on the flagship’s engaged side was still capable of firing, and Perry, along with Purser Hambleton and Chaplain Thomas Breese, helped man the gun. Eventually, even this lone defiant carronade was put out of action.

By 1430 it was obvious that the Lawrence could no longer resist. She was a drifting, helpless wreck—sails hung in tattered strips, rigging trailed like tangled kite string hanging from a tree, ugly gaps defiled the symmetry of her once beautiful sheers, and ragged furrows riddled the decks. No functioning gun remained on the starboard side, and four out of every five men fit for duty when the sun rose were now either killed or wounded. Standing on his smashed quarterdeck, Perry faced the seemingly inevitable prospect of surrender. But Perry’s vaunted luck had not totally deserted him—the American commodore was unwounded, and he was still defiant.

Often forgotten in discussions of the battle are the smaller vessels that supported the Lawrence at the head of Perry’s line. The Scorpion and Ariel fought the engagement ahead of and slightly to the windward of the Lawrence, positioned by Perry so as to prevent the British from crossing the Lawrence’s bow and raking his flagship. Astern of the Lawrence floated the Caledonia, commanded by Lieutenant Daniel Turner. Turner wisely slowed his vessel as it approached the British line, bringing his two long 24-pounders within range of the Queen Charlotte but keeping the little brig’s fragile timbers out of range of the enemy ship’s heavy 24-pounder carronades. Caledonia’s long guns and 32-pounder carronade were no match for the 17-gun Queen Charlotte. By his actions, Turner delayed the Niagara from immediately engaging the enemy. Elliott, obsessed with maintaining the line of battle, never thought of closing with the Queen Charlotte and remained astern the Caledonia, unable to reach the British line with his carronades. Instead he fired only with his 12-pound long guns.

Barclay never intended for any of these three small ships—Ariel, Scorpion, and Caledonia—to be principal targets for his concentrated guns. With the Niagara temporarily blocked behind the Caledonia, Barclay realized that victory hinged upon disabling the Lawrence before the Niagara could bring her heavy guns into action. Consequently, the Scorpion, Ariel, and Caledonia were targets for only occasional shots from the smaller British vessels. As a result they suffered only minor damage and few casualties. Enemy fire felled several crewmen, but the injuries sustained by the smaller vessels were caused less by British metal than by American carelessness and inexperience.

However, among those hit by enemy fire was Midshipman John Clarke of the Scorpion, killed instantly when he was struck in the head by a cannonball. Also killed by enemy fire on the same vessel was Pennsylvania militia private John Silhammer. On the Ariel Seaman Robert Wilson was slightly wounded, as was Landsman William Sloss, struck in the chest by a flying wood splinter. Not so lucky was Boatswain’s Mate John White, killed in action. More typical was an incident on board the Ariel when a 12-pounder was overloaded and toppled down a hatch. Private William Smith of the 26th Infantry Regiment neglected to release the gun tackle he was holding, and the rapidly running line burned through flesh, muscle, and sinew, rendering his hands into clenched claws for the rest of his life. Pennsylvania militia private John Lucas jumped too late from the gun recoil of one of the Ariel’s 12-pounders and had his foot crushed by the wheels of a heavy wooden gun truck. Before anyone could react, the gun slammed up against its breech tackle and rebounded forward, crushing poor Lucas’s foot a second time.25 Despite these losses, their fire had dire consequences to the British vessels. The Ariel’s and Scorpions guns raked Barclay’s two largest vessels, causing considerable consternation in the British line.

Well out of British carronade range, the Caledonia suffered but few casualties. Slightly wounded on the small brig were Kentucky militiamen James Artus and Isaac Perkins, and Seaman James Philips. Throughout the early part of the battle, the Caledonia supported the flagship with her two heavy long guns, never risking her thin hull by sailing close enough to use her carronade. Turner’s cannons caused some injury to the General Hunter, but it was against the Queen Charlotte that the Caledonia was most effective. Lieutenant Stokoe later stated that it was the Caledonia’s big guns that inflicted most of the damage to Barclay’s second-largest vessel.

The damage suffered by the American vessels, particularly the flagship, was horrible, but the destruction inflicted by Perry’s heavy guns was no less devastating to the Detroit and Queen Charlotte. Most critical was the British loss of officers and experienced seamen early in the engagement. Among the first to fall was “the noble & intrepid Captn. Finnis” of the Queen Charlotte, apparently felled by a shot from the Caledonia. Within moments, Lieutenant James C. Garden of the Royal Newfoundland Regiment, who was serving as the Queen’s marine lieutenant, was cut down. Thus the second-largest British vessel was without its most experienced officer at the outbreak of the action. On the Detroit, Barclay received a splinter wound in the thigh that sent him below for brief treatment before he crawled back to the quarterdeck. This was his seventh wound in His Majesty’s service. Lieutenant John Garland, first officer of the British flagship, was mortally wounded shortly after Barclay received his first wound of the day.

Wounds among the enlisted personnel were particularly severe. Of the ten experienced Royal Navy tars aboard the Detroit, at least seven were killed or wounded. Two Royal Newfoundlanders, Sergeant John Galpion (or Gilpin) of the Detroit and Private Robert Keilly of the General Hunter, lost their left arms at the shoulder. Other Newfoundlanders suffering severe wounds included Private James Butler and Corporal Matthew Ordell of the Detroit. Among the wounded from the 41st Foot were Privates William Essary, William Smith, Edward White, John Tivo, and Robert Sulvey of the Queen Charlotte, the latter two losing their right legs to amputation.26

Regardless of the damage to their ships, the grisly sight of maimed and mutilated comrades falling around them, and frustration with having to fire pistols to ignite the cannons, the British crews, every bit as brave and resolute as their American counterparts, continued to serve their guns and pound the Lawrence. Initially the British flagship found herself alone facing the fire of the Ariel, Scorpion, and Lawrence, but soon she received assistance of the Queen Charlotte. When her new commander, Lieutenant Thomas Stokoe, discovered that the Niagara would not closely engage her, he moved ahead of the General Hunter, adding his own carronades to the Detroit’s long-gun attack of the Lawrence. By breaking from the line of battle, Stokoe implemented Barclay’s desire to cripple or take one of the American brigs before the other could be fully engaged. Such a discretionary move was in the best tradition of the Royal Navy, where “formal tactics had come to be regarded as a means of getting at your enemy, and not as a substitute for initiative in fighting him.”27

Shortly after the Queen Charlotte came forward, Stokoe received a critical wound from a splinter and command devolved to the young, inexperienced Lieutenant Robert Irvine of the Provincial Marine. Apparently the Queen Charlotte was more to the lee of the Detroit than behind her in the line, thus limiting the full impact of her firepower upon the Lawrence. Although he behaved courageously, Lieutenant Irvine provided Barclay “far less assistance” than the commander expected. More importantly, the tenacity of the Lawrence’s crew and the impact of her heavy carronades kept the two Royal Navy ships fully engaged with one American brig, which they could not eliminate before they received severe damage.

Amid the gore on the Detroit’s deck was found the same macabre humor as found on the Lawrence. Barclay shipped on board his flagship two Sioux Indian sharpshooters and assigned them to pick off American officers. They did not long remain in their posts. When a number of American rounds crashed through the sails and rigging near them, they quickly descended to the deck, informed their “one-armed father” that the fire was particularly directed at them, and asked where they could go for safety. Barclay, fearing their timidity might disturb his own men, ordered them below. There they remained for two days after the battle, hidden in the cable tiers of the Detroit.28

As on the Lawrence, soon the rigging and sails of the Detroit and Queen Charlotte were cut and torn and their guns disabled. With Barclay receiving treatment for his wound and Garland dying, temporary command of the flagship and of the entire squadron now went to Barclay’s second lieutenant, George Inglis. Were this not enough, Lieutenants Edward Buchan and George Bignell of the Lady Prevost and General Hunter, respectively, received wounds that reduced their ability to command. The Lady Prevost lost her rudder and sailed to the leeward out of the engagement. By 1430, through sheer courage and determination, the British had managed to disable the Lawrence, rendering the American flagship hors de combat. Yet, despite their apparent victory over the Lawrence, at the battle’s most critical juncture the British command structure was in shambles, many of the key enlisted personnel were either dead or wounded, and the Detroit itself was “a perfect Wreck.”29

Where, one might ask, were Jesse Elliott in the Niagara and the trailing vessels? Why were they not seriously engaged during the more than two and a half hours in combat? These questions have bedeviled commentators on this engagement since the battle was fought, and they served as the central theme of a thirty-year controversy between Elliott, on the one hand, and Perry and his champions, on the other.

At 1145, when Perry signaled for his commanders to follow him and to engage their designated adversaries, Elliott kept the Niagara in line astern the Caledonia rather than sail in a line abreast of the Lawrence toward the Queen Charlotte. Although we are not entirely sure just which signal flags Perry used, he apparently did not hoist the signal designating his vessels to “form the order of sailing abreast.” Thus Elliott kept his vessel in a line of battle aft of the Caledonia, which was designated to engage the General Hunter. But Lieutenant Turner of the Caledonia, armed with two 24-pound long guns and only one 32-pound carronade, refused to engage at carronade range. His best tactic was to stand off and fire at long-gun range and not allow his lightly built converted merchantman to receive the impact of British carronade fire. This is what he did.30

By remaining astern the Caledonia rather than sailing abreast of Perry’s vessel toward the Queen Charlotte, Elliott delayed the time when the Niagara could come within carronade range of her designated foe. The two squadrons converged at an angle of 15 degrees. While Perry brought the Lawrence directly toward the British line, Elliott and the trailing vessels converged much more slowly. As British naval tactician John Clerk of Eldin noted in 1797, such slanting attacks on an enemy’s van generally proved unsatisfactory, since they delayed the ability of the trailing vessels to engage their designated foes. The “great bugbear of all admirals attacking from the windward,” as Perry was doing, was bringing the “fleet into action simultaneously.” This line-abreast approach was utilized by Admiral Richard Lord Howe and proved a significant factor in his victory over the French in the Glorious First of June in 1794.31

Elliott chose to follow the traditional British fighting instruction not to break the line of battle. In other words, Elliott was unimaginative when it came to employing his ship. Because Turner’s best and smartest tactic was to slow the Caledonia, stand off, and make the most of his heavy long guns, it was not in Elliott’s best interest to remain directly astern the thin-walled merchantman ahead of him. When the Caledonia slowed, Elliott faced a dilemma. If he failed to take immediate action, his ship would collide with the Caledonia. Elliott made a quick decision; he passed the order to back the Niagara’s main topsail to brail up his jib. By remaining in line astern of the Caledonia, Elliott was simply obeying his commodore’s order to “maintain your station in line.” Elliott could not be blamed for following orders, but by so doing, especially since the Caledonia had reduced sail and slowed, he also guaranteed that the Niagara would not be able to close within carronade range of her designated adversary, the Queen Charlotte.

Elliott tried loosing a carronade broadside, but the rounds fell short. Now that he was sailing abaft the Caledonia, only the Niagara’s 12-pounder bow chaser could reach his designated foe. Attempting to increase his firepower, Elliott moved his larboard bow chaser to a starboard gunport, doubling his fire, but the two had little effect on the Queen Charlotte. As noted earlier, upon observing that his carronades could not reach the Niagara, Thomas Stokoe, as acting captain of the Queen Charlotte, broke the British line of battle and joined the attack against the Lawrence. The Niagara did sustain light damage and casualties, but nothing comparable with that on the Lawrence.

Unknown for certain is precisely when Stokoe made his decision to pass the General Hunter. Perry would later contend that Stokoe came forward early in the contest, whereas Elliott would have one believe that the Queen Charlotte moved forward to escape the punishment of Niagara’s two 12-pounders. Elliott later claimed that he passed the Caledonia shortly after the Queen Charlotte moved forward. However, testimony by Midshipman and Acting Sailing Master Nelson Webster of the Niagara indicates that the Queen Charlotte moved out of range of the Niagara’s long guns at about 1300.32

Also uncertain is the point in time when Elliott decided to pass the Caledonia. Elliott later confessed that he did not come forward until Purser Humphrey Magrath pointed out “the slackening fire of the Lawrence and her crippled condition.” (Nothing is so telling of Elliott’s indecision than his dependence upon Purser Magrath for advice, a man Elliott testified was “as good a seaman perhaps as our Navy ever had in it.”) It would appear that over an hour ensued between when the Queen Charlotte passed General Hunter and Elliott ordered the Niagara to come forward. What was the Niagara doing during this time? We know she expended most of her 12-pounder ammunition prior to her move past the Caledonia. At which ship did she fire it? More significantly, when Queen Charlotte left the British line she left a huge gap in the Royal Navy line of battle. Elliott had an ideal opportunity to break the British line by sailing through this gap and raking his opponent’s line. An effective subordinate would have exploited this chance and decisively engaged his ship, saving numerous lives on board the Lawrence, which Elliott admittedly did not support until she was “crippled.” It is difficult to believe Elliott did not know what was happening at the head of the line and that his fellow countrymen were dying while he maintained his place in line. Certainly his order to engage his designated foe in close action superseded any requirement to maintain the line of battle.

Elliott’s mistake was not that he disobeyed orders—he followed one to a fault—but rather that he failed to place service to the squadron as his highest priority. In this he conducted himself not unlike Admiral Sir Samuel Hood at the battle of the Chesapeake Capes in 1781. There Hood deliberately undermined his superior and, as would Elliott, sheltered his conduct behind a fictitious adherence to the line rather than doing his utmost in performing his duty to engage his foe. At what was to be the most crucial moment of his career, Elliott failed to exhibit the best of naval professionalism. Unfortunately, conduct like that of Hood and Elliott was all too common in the age of fighting sail.33

When Elliott finally decided to come forward, he hurried to the Niagara’s forecastle and through a speaking trumpet called to Lieutenant Turner to put up his helm to allow the Niagara to pass. By this time, Niagara’s flying jibboom loomed over the Caledonia’s stern. Although he was reluctant to do so, Turner eventually eased his helm enough to allow Elliott to pass. Elliott now sailed the Niagara to windward of the American line, a maneuver that placed first the Caledonia and then eventually the Lawrence between his own vessel and the British line. Consequently, for the entire period he was passing the two American vessels, his guns were masked from the enemy. This maneuver has been roundly condemned by those who argue that Elliott should have sailed to the leeward of the Caledonia and protected the Lawrence from enemy fire while coming forward. But Purser Magrath, a former navy lieutenant, advised that if Niagara moved to the leeward, Elliott might create an opportunity for Barclay to seize the weather gauge. Again, Elliott accepted Magrath’s argument. In sailing to the windward, Elliott may have recognized the possibility of passing through the head of the Royal Navy line and inflicting raking fire down the enemy squadron’s line. Elliott also thought he might now be squadron commander, since “the Lawrence ceased her fire entirely, and no signal being made, after the first, to form in the order of battle, I concluded that the senior officer was killed.”34

This comment of Elliott’s points to the most effective criticism of Perry’s conduct during the early stages of the battle. The commodore issued no signal for the Niagara or any other vessel to maneuver after hoisting the initial flag around noon. Perry was so immersed in captaining the Lawrence in her contest against the Detroit that he failed to effectively maneuver his entire squadron. No one has more pointedly enunciated this criticism than Elliott’s most effective defender, James Fenimore Cooper: “Capt. Perry, had given him [Elliott] a station in the line, astern of the Caledonia, that he enjoined it on him to keep that station, and it was for him who gave the order, to take the responsibility of changing his own line of battle, if circumstances required a change.” Such a change could have been given by signal flags or by sending a messenger in a boat. Neither was done.35 Cooper’s defense of Elliott placed its emphasis on the maintenance of the line rather than on Perry’s charge that each commanding officer engage his designated adversary—in Elliott’s case, the Queen Charlotte. Certainly Elliott had more of an obligation to engage his designated foe at a range allowing him to fire his heaviest weapons than to remain astern the Caledonia.

And what of the four trailing vessels with the five long guns? They still lagged behind, but with sweeps working they were laboring to catch up. The breeze freshened as the afternoon wore on, enabling them to close up even faster. About the time Elliott began moving forward, the smaller vessels began closing much of the gap between themselves and the British rear. Their raking fire fell upon the rear of two British ships, the Lady Prevost and Little Belt. Rather than endure the pounding of the American long guns, to which they could not reply, the Lady Prevost and Little Belt set sail and moved toward the head of the British line, toward the lee of the Queen Charlotte.36 Particular credit must be given to Lieutenant Thomas Holdup of the Trippe, who moved from the trailing position in the American line past the Tigress, Porcupine, and Somers to lead the final four U.S. vessels.

In the midst of this delicate and changing situation, Perry made a crucial decision that would gain him immortality in American naval annals. Undoubtedly, pride swelled in Perry’s chest at the superb performance and sacrifice manifested by his crew, some of whom he once maligned as “a motley set, blacks, Soldiers and boys.” Staring at the words emblazoned on his battle standard, still straining against its halyard at the maintop, he realized he had no choice but to betray its unyielding tenor and abandon his precious ship. Perry conferred with the thrice-wounded Lieutenant John Yarnall and determined that continued resistance by the Lawrence would be suicidal. But Perry refused to surrender his brig and with it his entire squadron. In other words, he was not going to imitate either General William Hull at Detroit or General James Winchester at the River Raisin and surrender while there still existed a chance to resist. Instead, Perry placed Yarnall in command of the Lawrence and determined to transfer the commodore’s flag to the Niagara. Private Hosea Sergeant of the 17th U.S. Infantry, serving as a volunteer and working at the aftmost gun, helped haul down the “Don’t Give Up the Ship” flag and personally handed it to the commodore. Perry might give up his ship, but he was determined not to give up the fight. He rounded up four unwounded seamen and hauled the slightly damaged first cutter alongside to the larboard. Years later Midshipman Dulany Forrest recalled informing Perry of his disgust at Elliott’s delinquency before the commodore left the Lawrence. Perry reportedly replied, “If a victory is to be gained, I’ll gain it.” Jumping aboard this small boat, Perry embarked upon his momentous journey to the Niagara. (Despite the iconography of this event, which depicts Perry’s thirteen-year-old brother, Midshipman James Alexander Perry, at the tiller, there is no evidence that he made the trip.)37

As the Lawrence drifted astern of the Niagara, Barclay perceived Perry’s movement, comprehended his objective, and directed fire upon the small boat as it moved toward the Niagara. Straining at the oars, the exhausted sailors were spurred on by the incessant splash of British shot, which somehow never found its mark. Perry escaped unharmed and boarded the American brig on her windward (larboard) side.

One can only imagine the turmoil that Elliott felt as his commodore, who he had only moments earlier assumed was either dead or wounded so badly that he could no longer function as the squadron’s commander, now boarded his vessel. Perry, too, must have been in considerable distress in the midst of the long battle. The exchange between them has been variously reported, its substance roughly the same in each telling. What is startling to the modern observer is that Perry made no recriminations against Elliott for dereliction of duty. (Part of this may reflect the fact that only Elliott’s supporters report the conversation. But Perry never contradicted these reports. Perry may have not realized the degree of nonperformance on Elliott’s part, or he may have made a command decision not to force the issue in the midst of a battle.) Instead, Perry focused on the trailing gunboats. According to Captain Brevoort, the exchange went somewhat like this:

“I am afraid the day is lost,” said the commodore. “Two-thirds of my men are either killed or wounded and the Lawrence can provide no further assistance. The damned gunboats have ruined me.”

“No!” said Elliott, “I can save it!”

“I wish to God you would,” said Perry.

“Take charge of my battery [the guns of the Niagara] while I bring the gunboats into close action, and the day will yet be ours.”38

Perry later wrote the secretary of the navy that Elliott “anticipated my wishes, by volunteering to bring the Schooners, which had been kept astern by the lightness of the wind, into closer action.”39 Years later Elliott would claim that Perry was shaking like a leaf when he came on board. Whatever Perry’s condition at the time, he was aware that the Niagara was in an ideal position to break the British line. He was probably dismayed that the gunboats were firing at the smaller vessels of the British flotilla rather than at the principal vessels, where the issue would be decided. Not wanting to remain on the Niagara, Elliott volunteered to bring up the trailing gunboats. Such a change provided him with a separate command at the critical juncture in the battle. Otherwise he would merely be a flag captain on the commodore’s vessel. If Elliott really said “I can save” the day, then he had a monumental ego rivaling that of Generals George McClellan and Douglas MacArthur.

Another source of controversy concerns the exact position of the Niagara and her degree of engagement when Perry boarded her. Perry’s partisans would have the Niagara hundreds of yards to the windward of the Lawrence and out of carronade range of any British vessels. Elliott and his officers contend the Niagara was close to the flagship and was firing every gun she could at the British line before the commodore arrived on board. In his official report following the battle, Perry wrote that by Elliott’s maneuvering the Niagara to the windward of the Lawrence, the lieutenant was “enabled to bring . . . the Niagara, gallantly into close action.” But was she really in close action before Perry arrived? Or was she merely “enabled” to be so? Despite Elliott’s argument that he luffed 250 yards off the Detroit and was firing all his starboard carronades before Perry boarded the Niagara, there is little corroboratory evidence to this effect. It is an established fact that Perry had to set additional sail in order for the Niagara to close on the British line.40 Accounts also vary as to the number of casualties and the extent of damage suffered by the Niagara prior to Perry boarding her. Best estimates have the Niagara suffering two wounded and no significant material damage. It would appear that the distance between the Niagara and the Lawrence was not great, since Perry took only a few minutes to reach his relief flagship. On the other hand, the Niagara was probably not within carronade range when Perry boarded her, nor had she suffered much.

The Battle of Lake Erie at 1440 hours

Aboard the Lawrence, Lieutenants Yarnall and Forrest, along with Sailing Master Taylor, determined further resistance was futile and, “to save the further effusion of human blood,” ordered the national ensign struck. When news of the surrender spread to the wounded in the wardroom, cries of “Sink the ship” and “Let us all sink together” resounded among the bloodied crewmen.41 To the leeward of the Lawrence, cheering broke out on board the Detroit and Queen Charlotte—the British thought they had won the day. Unable to find a serviceable ship’s boat, Barclay, who had returned to the quarterdeck with his wound dressed, could not send a boarding party across to the Lawrence to accept her surrender. Moreover, just when victory seemed certain because of the American flagship’s surrender, disaster loomed in the form of the approaching Niagara. Precisely when he was most needed to counteract the new threat, Barclay received some grape shot, a severe wound that shattered his right shoulder and forced him below to the surgeon. For the eighth time in his career, Robert Heriot Barclay had been wounded in His Majesty’s service. Command of the flagship and of the entire squadron now devolved upon Barclay’s second lieutenant, George Inglis. Meanwhile, the Lawrence drifted out of the battle as the other vessels sailed past her.

Following his offer to expedite the gunboats, Elliott, along with Purser Magrath, boarded Perry’s cutter and rapidly rowed to the American rear. Reaching the gunboats, Elliott ordered their captains “to make sail, get out the sweeps and press up for the head of the line, and to cease firing on the small vessels of the enemy astern.” As the Trippe’s crewmen manhandled the awkward sweeps and pulled hard to close the gap between themselves and the British vessels, the little ship’s commander, Thomas Holdup, told the crew that when he said “squat” the men “should squat to the deck and the bulwarks would save” them from British small shot. The Trippe bore down on the British line, maneuvering near the stern of the Detroit, but the position also exposed the sloop to fire from the Queen Charlotte. Meanwhile, Elliott boarded the schooner Somers, shortened her sail, and with the four gunboats abreast, blasted away at the sterns of the Detroit and Queen Charlotte. The raking fire of the gunboats’ 32-pounders was devastating and demoralizing to the British.42

As the gunboats were closing astern of the British, Perry hoisted his battle flag to the topmast of the Niagara, ordered all fighting sail set, and set course for the center of the British line. The menacing approach of the undamaged Niagara convinced Lieutenant Inglis of the need to take remedial action. With many of his larboard guns unserviceable, Inglis knew that his only hope was to wear ship—turn it 180 degrees from the wind—and bring his undamaged starboard battery to bear. Wearing a ship in a light breeze is not difficult with experienced officers and seamen, but by now the Royal Navy veterans were few and the remaining crewmen, mostly soldiers, had gained little experience with sail drill prior to the battle. As the British sailors and soldiers strained at the braces, attempting to haul the damaged yards around, the Detroit sluggishly started to turn, her movements painfully slow due to her shot-riddled top-hamper.43 Astern of the Detroit, Lieutenant Robert Irvine on the Queen Charlotte endeavored to follow the Detroit’s lead, but his inexperienced eye misjudged the flagship’s languid maneuver. Unable to compensate in time, the Queen Charlotte inexorably bore down on the Detroit, helplessly ramming her head booms squarely into the Detroit’s tangled mizzen rigging. Now, at the most crucial stage of the battle, the two largest British ships were locked together and powerless to maneuver.

The Battle of Lake Erie at 1500 hours

Just at this moment, with the long guns of the American gunboats beginning to rake Barclay’s two largest vessels from the stern, Perry sailed the Niagara to the center of the British line. With three British ships to starboard and three more to larboard, the American commodore unleashed both of the Niagara’s double-shotted broadsides with devastating effect. Two by two the Niagara’s guns fired as she glided past the Detroit to starboard and the Lady Prevost and Little Belt to larboard. Twin flashes rippled down the Niagara’s gunports; the ship shuddered in an effort to absorb simultaneous recoils from opposite sides. Acrid, dirty white gunsmoke soon enshrouded the flagship, while the mind-numbing blasts furrowed Lake Erie’s waters as the deadly cannonballs sped upon their destructive mission. Niagara’s crammed gun deck appeared disorganized and confused, but it was disciplined chaos, each and every man performing a specific, designated task to keep the big guns firing. On and on it continued, the gun captains shouting themselves hoarse repeating the gun drill: “Sponge!” . . . “Load!” . . . “Fire!” . . . “Sponge!” . . . “Load!” . . . “Fire!”

British axes frantically chopped away at entangled spars and rigging that securely fastened their two largest vessels together. Despite their predicament, Barclay’s men continued the fight, inflicting casualties upon the Americans, especially on the Niagara. Three enlisted men of the 28th Infantry Regiment serving as marines were among the wounded: Sergeant Sanford Mason received a musket ball to the thigh; splinters splattered Private George McManomy in both legs and his right arm; and shrapnel struck Private John Reams above the left temple, shearing off a large chunk of his skull at the hairline, leaving him partially paralyzed and with impaired speech. Serving in the capacity of an ordinary seaman, Private Rosewell Hale of the 1st U.S. Light Dragoons received a musket ball in the right thigh, and Seaman James Lansford also took a bullet wound to the leg. Fatally cut down was Private Joshua Trapnell of the 17th U.S. Infantry.44

Although spared the level of destruction experienced by the Niagara, the gunboats bringing up the American rear received their share of casualties. A Pennsylvania militiaman, Private William Brady of the Trippe, volunteered to man that vessel’s 24-pounder pivot gun as a shot-and-wad man. Somewhat overzealous to carry out his duties, Brady’s shirtsleeve was ripped away and he received a contusion on his arm. At one point, just as the order was given to fire, Captain Holdup yelled for the men to squat as small-arms fire came in from the Queen Charlotte. Brady turned to squat just as the 24-pounder fired, and when the gun slammed back in recoil, a heavy wood tackle block smashed into his knee. According to the private, “The pain was acute, but the anxiety to conquer and the excitement of the moment bore me above a little suffering.” Also aboard the Trippe was Isaac Green, a private in the 27th U.S. Infantry, who received a serious wound from the Queen Charlotte. The Trippe’s pilot, Patrick FitzPatrick, at fifty-five certainly one of the oldest men in the American fleet, failed to protect his ears from the sharp bark of the ship’s long gun, an omission that permanently cost him his hearing. An unfortunate crewman on the Tigress, Private Harvey Harrington of the 27th U.S. Infantry, finished the battle with blood draining from his ears and lifelong deafness.45

After turbulent minutes of hacking and slashing, with many of those wielding the axes cut down by American fire in the process, the Detroit and Queen Charlotte cleared the entangled rigging and drifted apart. But it was too late. Dozens of jagged holes disfigured the flanks of Barclay’s ships, with more gaps appearing every time an American gun was fired at point-blank range. Masts quivered like trees feeling the ax; loud tearing noises presaged the shredding of blossoming canvas; hundreds of deadly wood splinters flew across the disarrayed decks; British and Canadian blood flowed freely. On the larboard side of the Detroit most of the guns were dismounted, and a hand could not be placed on the hull without touching evidence of the impact of American grape, canister, or round shot.

For the British only one option remained. The Detroit, with her imposing ensign nailed to the mast to symbolize Barclay’s determination not to surrender, signaled her capitulation by firing a gun off her disengaged side. A white flag slowly ascended from the Queen Charlotte’s deck, and the General Hunter and Lady Prevost struck their colors. The two smallest British vessels, the Chippawa and Little Belt, shook out their sails and set course for the Detroit River, closely pursued by the Scorpion and Trippe. The latter sloop, which began the day at the tail of the American line, now headed it. A stern chase ensued until near misses splashing alongside the two Royal Navy vessels impressed upon their captains the futility of flight; the last enemy vessels capitulated. Firing the last round of the day was the Scorpion, which had fired the first shot for the United States. The entire flotilla was in American hands. It was one of the rare times in British history that the Royal Navy lost an entire squadron.

The first American officer to board the Detroit was Elliott, who was brought alongside by the Somers’s gig. As he stepped onto the bloody deck, his feet slipped from under him and he fell; before he could get up his uniform became saturated with blood and gore. Upon regaining his feet, Elliott inspected the bloody shambles that had been the Detroit’s gundeck. He gazed upon a repugnant sight. Slated to serve as the main course for the British victory celebration, the black bear, which Barclay had so confidently brought on board his flagship, was instead shuffling about, lapping up British and Canadian blood. After stepping around the bodies and body parts, the moaning wounded and the wreckage, Elliott went below to see to Captain Barclay, who tendered him his sword. He refused it; this was an honor for Perry. Before leaving, Elliott ordered his coxswain to scramble up the stump that had been the flagship’s mizzenmast to retrieve the royal ensign. Elliott secured the flag and presumably gave it to Perry; he kept the nails for himself. He later gave the nails to his congressional patron, House Speaker Henry Clay.46

Covered with blood from his fall, Elliott returned to the Niagara, where he was met at the gangway by Perry. According to Elliott, Perry first asked if he were wounded. When the second-in-command replied in the negative, Perry expressed his astonishment that Elliott could be rowed down the whole line without being hit. Reputedly Perry then remarked to Elliott, “I owe this victory to your gallantry!” Then Elliott introduced an issue that would be central to the resulting controversy—Why did Perry not allow the squadron to close up before he went dashing toward the Detroit? Elliott’s version of Perry’s reply was that the commodore “found the enemy’s shot taking effect on his crew, and therefore, to divert attention of his men from their fire, he rounded to sooner than he intended.”47 In his graciousness or in his ignorance of what had happened, Perry did not ask Elliott why, for more than two hours, the Niagara had failed to engage the Queen Charlotte in close action.

At first the silence, after three hours of earsplitting pandemonium, was startling; slowly Perry began to grasp the enormity of his success. General Harrison and Secretary Jones must be informed. Finding an old letter, Perry hastily scribbled a note in pencil on the back of an envelope:

Dear General:

We have met the enemy and they are ours: Two Ships, two Brigs, one Schooner, and one Sloop.

Yours, with great respect and esteem,

O. H. Perry

“We have met the enemy and they are ours” is one of the most graphic, succinct, and accurate after-action reports in history. It rivals Julius Caesar’s famous Veni, vidi, vici—”I came, I saw, I conquered.” Less than an hour after his victory, Perry also dashed off a brief summary for the secretary of the navy: “It has pleased the Almighty to give to the arms of the United States a signal victory over their enemies on this Lake—The British squadron consisting of two Ships, two Brigs, one Schooner & one Sloop have this moment surrendered to the force under my command, after a Sharp conflict.”48

For Oliver Hazard Perry, his officers, and his men, it was indeed “a signal victory.”