This interval of geologic time was the last of the three periods of the Mesozoic Era. The Cretaceous began 145.5 million years ago and ended 65.5 million years ago. It followed the Jurassic Period and was succeeded by the Paleogene Period of the Cenozoic Era. The Cretaceous is the longest period of the Phanerozoic Eon. Spanning 80 million years, it represents more time than has elapsed since the extinction of the dinosaurs, which occurred at the end of the period.

The name Cretaceous is derived from creta, Latin for “chalk,” and was first proposed by J.B.J. Omalius d’Halloy in 1822. D’Halloy had been commissioned to make a geologic map of France, and part of his task was to decide upon the geologic units to be represented by it. One of his units, the Terrain Crétacé, included chalks and underlying sands. Chalk is a soft, fine-grained type of limestone composed predominantly of the armourlike plates of coccolithophores, tiny floating algae that flourished during the Late Cretaceous (about 100 million to 65.5 million years ago). Most Cretaceous rocks are not chalks, but most chalks were deposited during the Cretaceous. Many of these rocks provide clear and easily accessed details of the period because they have not been deformed or eroded and are relatively close to the surface—as can be seen in the white cliffs bordering the Strait of Dover between France and England.

The Cretaceous Period began with the Earth’s land assembled essentially into two continents, Laurasia in the north and Gondwana in the south. These were almost completely separated by the equatorial Tethys seaway, and the various segments of Laurasia and Gondwana had already started to rift apart. North America had just begun pulling away from Eurasia during the Jurassic, and South America had started to split off from Africa, from which India, Australia, and Antarctica were also separating. When the Cretaceous Period ended, most of the present-day continents were separated from each other by expanses of water such as the North and South Atlantic Ocean. At the end of the period, India was adrift in the Indian Ocean, and Australia was still connected to Antarctica.

The climate was generally warmer and more humid than today, probably because of very active volcanism associated with unusually high rates of seafloor spreading. The polar regions were free of continental ice sheets, their land instead covered by forest. Dinosaurs roamed Antarctica, even with its long winter night.

The lengthy Cretaceous Period constitutes a major portion of the interval between ancient life-forms and those that dominate Earth today. Dinosaurs were the dominant group of land animals, especially “duck-billed” dinosaurs (hadrosaurs), such as Shantungosaurus, and horned forms, such as Triceratops. Giant marine reptiles such as ichthyosaurs, mosasaurs, and plesiosaurs were common in the seas, and flying reptiles (pterosaurs) dominated the sky. Flowering plants (angiosperms) arose close to the beginning of the Cretaceous and became more abundant as the period progressed. The Late Cretaceous was a time of great productivity in the world’s oceans, as borne out by the deposition of thick beds of chalk in western Europe, eastern Russia, southern Scandinavia, the Gulf Coast of North America, and western Australia. The Cretaceous ended with one of the greatest mass extinctions in the history of Earth, exterminating the dinosaurs, marine and flying reptiles, and many marine invertebrates.

When the Cretaceous Period began, Earth’s continents were joined into two large, continuous blocks. By the end of the period, these blocks had separated into multiple smaller pieces. Although sea level crested during the Cretaceous, producing vast areas of shallow seas, the close proximity of the landmasses inhibited ocean circulation. In addition, by the middle of the period, average temperatures had climbed to their highest level in Earth’s history. Reduced ocean circulation combined with warm temperatures stripped the oxygen from equatorial seas, enabling the development of black shale deposits.

The position of Earth’s landmasses changed significantly during the Cretaceous Period—not unexpected, given its long duration. At the onset of the period there existed two supercontinents, Gondwana in the south and Laurasia in the north. South America, Africa (including the adjoining pieces of what are now the Arabian Peninsula and the Middle East), Antarctica, Australia, India, Madagascar, and several smaller landmasses were joined in Gondwana in the south, while North America, Greenland, and Eurasia (including Southeast Asia) formed Laurasia. Africa had split from South America, the last land connection being between Brazil and Nigeria. As a result, the South Atlantic Ocean joined with the widening North Atlantic. In the region of the Indian Ocean, Africa and Madagascar separated from India, Australia, and Antarctica in Late Jurassic to Early Cretaceous times (145.5 million to 99.6 million years ago). Once separated from Australia and Antarctica, India began its journey northward, which culminated in a later collision with Asia during the Cenozoic Era. Madagascar broke away from Africa during the Late Cretaceous, and Greenland separated from North America. Australia was still joined to Antarctica. These were barely attached at the junction of what are now North and South America.

Sea level was higher during most of the Cretaceous than at any other time in Earth history, and it was a major factor influencing the paleogeography of the period. In general, world oceans were about 100 to 200 metres (330 to 660 feet) higher in the Early Cretaceous and roughly 200 to 250 metres (660 to 820 feet) higher in the Late Cretaceous than at present. The high Cretaceous sea level is thought to have been primarily the result of water in the ocean basins being displaced by the enlargement of midoceanic ridges.

As a result of higher sea levels during the Late Cretaceous, marine waters inundated the continents, creating relatively shallow epicontinental seas in North America, South America, Europe, Russia, Africa, and Australia. In addition, all continents shrank somewhat as their margins flooded. At its maximum, land covered only about 18 percent of the Earth’s surface, compared with approximately 28 percent today. At times, Arctic waters were connected to the Tethys seaway through the middle of North America and the central portion of Russia. On several occasions during the Cretaceous, marine animals living in the South Atlantic had a seaway for migration to Tethys via what is presently Nigeria, Niger, Chad, and Libya. Most of western Europe, eastern Australia, parts of Africa, South America, India, Madagascar, Borneo, and other areas that are now land were entirely covered by marine waters for some interval of Cretaceous time.

Detailed study indicates 5 to 15 different episodes of rises and falls in sea level. The patterns of changes for the stable areas throughout history are quite similar, although several differences are notable. During most of the Early Cretaceous, parts of Arctic Canada, Russia, and western Australia were underwater, but most of the other areas were not. During the Middle Cretaceous, east-central Australia experienced major inundations called transgressions. In the Late Cretaceous, most continental landmasses were transgressed but not always at the same time. One explanation for the lack of a synchronous record is the concept of geoidal eustacy, in which, it is suggested, as the Earth’s continents move about, the oceans bulge at some places to compensate. Eustacy would result in sea level being different from ocean basin to ocean basin.

Water circulation and mixing were not as great as they are today, because most of the oceans (e.g., the developing North Atlantic) were constricted, and the temperature differences between the poles and the Equator were minimal. Thus, the oceans experienced frequent periods of anoxic (oxygenless) conditions in the bottom waters that reveal themselves today as black shales. Sometimes, particularly during the mid-Cretaceous, conditions extended to epicontinental seas, as attested by deposits of black shales in the western interior of North America.

The Cretaceous world had three distinct geographic subdivisions: the northern boreal, the southern boreal, and the Tethyan region. The Tethyan region separated the two boreal regions and is recognized by the presence of fossilized reef-forming rudist bivalves, corals, larger foraminiferans, and certain ammonites that inhabited only the warmer Tethyan waters. Early in the Cretaceous, North and South America separated sufficiently for the marine connection between the Tethys Sea and the Pacific to deepen substantially. The Tethys-to-Pacific marine connection allowed for a strong westward-flowing current, which is inferred from faunal patterns. For example, as the Cretaceous progressed, the similarity between rudist bivalves of the Caribbean and western Europe decreased, while some Caribbean forms have been found on Pacific seamounts, in Southeast Asia, and possibly in the Balkans.

The remnants of the northern boreal realm in North America, Europe, Russia, and Japan have been extensively studied. It is known, for instance, that sediments in the southwestern Netherlands indicate several changes of temperature during the Late Cretaceous. These temperature swings imply that the boundary between the northern boreal areas and the Tethys region was not constant with time. Russian workers recognize six paleobiogeographic zones: boreal, which in this context is equivalent to Arctic; European; Mediterranean, including the central Asian province; Pacific; and two paleofloristic zonations of land. Southern boreal areas and the rocks representing the southern Tethys margin lack this level of detail.

Magnetically, the Cretaceous was quiet relative to the subsequent Paleogene Period. In fact, magnetic reversals are not noted for a period of some 42 million years, from the early Aptian to the late Santonian ages. The lengths of Earth’s months have changed regularly for at least the past 600 million years because of tidal friction and other forces that slow the Earth’s rotation. The rate of change in the synodic month was minimal for most of the Cretaceous but has accelerated since. The reasons for these two anomalies are not well understood.

In general, the climate of the Cretaceous Period was much warmer than at present, perhaps the warmest on a worldwide basis than at any other time during the Phanerozoic Eon. The climate was also more equable in that the temperature difference between the poles and the Equator was about one-half that of the present. Floral evidence suggests that tropical to subtropical conditions existed as far as 45° N, and temperate conditions extended to the poles. Evaporites are plentiful in Early Cretaceous rocks—a fact that seems to indicate an arid climate, though it may have resulted more from constricted ocean basins than from climatic effects. The occurrence of evaporites mainly between latitudes 10° and 30° N suggests arid subtropics, but the presence of coals poleward of 30° indicates humid midlatitudes. Occurrences of Early Cretaceous bauxite and laterite, which are products of deep weathering in warm climates with seasonal rainfall, support the notion of humid midlatitudes.

Temperatures were lower at the beginning of the period, rising to a maximum in the mid-Cretaceous and then declining slightly with time until a more accentuated cooling during the last two ages of the period. Ice sheets and glaciers were almost entirely absent except in the high mountains, so, although the end of the Cretaceous was coolest, it was still much warmer than it is today.

Models of the Earth’s climate for the mid-Cretaceous based on the positions of the continents, location of water bodies, and topography suggest that winds were weaker than at present. Westerly winds were dominant in the lower to midlatitudes of the Pacific for the entire year. In the North Atlantic, however, winds blew from the west during winter but from the east during summer. Surface water temperatures were about 30 °C (86 °F) at the Equator year-round, but at the poles they were 14 °C (57 °F) in winter and 17 °C (63 °F) in summer. A temperature of 17 °C is suggested for the ocean bottom during the Albian Age, but it may have declined to 10 °C (50 °F) by the Maastrichtian. These temperature values have been calculated from oxygen isotope measurements of the calcitic remains of marine organisms. The data support models that suggest diminished ocean circulation both vertically and latitudinally. As stated in the section Paleogeography, above, low circulation could account for the periods of black shale deposition during the Cretaceous.

Other paleontological indicators suggest details of ocean circulation. The occurrence of early and mid-Cretaceous rudists and larger Tethyan foraminiferans in Japan may very well mean that there was a warm and northward-flowing current in the region. A similar occurrence of these organisms in Aptian-Albian sediments as far south as southern Tanzania seems to indicate a southward-flowing current along the east coast of Africa. The fact that certain warm-water life-forms found in the area of present-day Argentina are absent from the west coast of Africa suggests a counterclockwise gyre in the South Atlantic. In addition, the presence of larger foraminiferans in Newfoundland and Ireland indicates the development of a “proto-Gulf Stream” by the mid-Cretaceous.

The Cretaceous Period is biologically significant because it is a major part of the transition from the early life-forms of the Paleozoic Era to the advanced diversity of the current Cenozoic Era. For example, most if not all of the flowering plants (angiosperms) made their first appearance during the Cretaceous. Although dinosaurs were the dominant animals of the period, many modern animals, including the placental mammals, made their debut during the Cretaceous. Other groups—such as clams and snails, snakes and lizards, and most fishes—developed distinctively modern characteristics before the mass extinction marking the end of the period.

The marine realm can be divided into two paleobiogeographic regions, the Tethyan and the boreal. This division is based on the occurrence of rudist-dominated organic reeflike structures. Rudists were large, rather unusual bivalves that had one valve shaped like a cylindrical vase and another that resembled a flattened cap. The rudists were generally dominant over the corals as framework builders. They rarely existed outside the Tethyan region, and the few varieties found elsewhere did not create reeflike structures. Rudist reeflike structures of Cretaceous age serve as reservoir rocks for petroleum in Mexico, Venezuela, and the Middle East.

Other organisms almost entirely restricted to the Tethys region were actaeonellid and nerineid snails, colonial corals, calcareous algae, larger bottom-dwelling (benthic) foraminiferans, and certain kinds of ammonites and echinoids. In contrast, belemnites were apparently confined to the colder boreal waters. Important bivalves of the boreal realm were the reclining forms (e.g., Exogyra and Gryphaea) and the inoceramids, which were particularly widespread and are now useful for distinguishing among biostratigraphic zones.

Marine plankton took on a distinctly modern appearance by the end of the Cretaceous. The coccolithophores became so abundant in the Late Cretaceous that vast quantities accumulated to form the substance for which the Cretaceous Period was named—chalk. The planktonic foraminiferans also contributed greatly to fine-grained calcareous sediments. Less-abundant but important single-celled animals and plants of the Cretaceous include the diatoms, radiolarians, and dinoflagellates. Other significant marine forms of minute size were the ostracods and calpionellids.

Ammonites were numerous and were represented by a variety of forms ranging from the more-usual coiled types to straight forms. Some of the more-unusual ammonites, called heteromorphs, were shaped like fat corkscrews and hairpins. Such aberrant forms most certainly had difficulty moving about. Ammonites preyed on other free-swimming or benthic invertebrates and were themselves prey to many larger animals, including the marine reptiles called mosasaurs.

Fossils of coiled ammonites. Ross Rappaport/Photonica/Getty Images

Other marine reptiles were the long-necked plesiosaurs and the more fishlike ichthyosaurs. Sharks and rays (chondrichthians) also were marine predators, as were the teleost (ray-finned) fishes. One Cretaceous fish, Xiphactinus, grew to more than 4.5 metres (15 feet) and is the largest known teleost.

Although the fossil record is irregular in quality and quantity for the Early Cretaceous, it is obvious that dinosaurs continued their lengthy dominance of the land. The Late Cretaceous record is much more complete, particularly in the case of North America and Asia. It is known, for instance, that during the Late Cretaceous many dinosaur types lived in relationships not unlike the present-day terrestrial mammal communities. Although the larger dinosaurs, such as the carnivorous Tyrannosaurus and the herbivorous Iguanodon, are the best-known, many smaller forms also lived in Cretaceous times. Triceratops, a large three-horned dinosaur, inhabited western North America during the Maastrichtian age.

Various types of small mammals that are now extinct existed during the Triassic and Jurassic, but two important groups of modern mammals evolved during the Cretaceous. Placental mammals, which include most modern mammals (e.g., rodents, cats, whales, cows, and primates), evolved during the Late Cretaceous. Although almost all were smaller than present-day rabbits, the Cretaceous placentals were poised to take over terrestrial environments as soon as the dinosaurs vanished. Another mammal group, the marsupials, evolved during the Cretaceous as well. This group includes the native species of Australia, such as kangaroos and koalas, and the North American opossum.

In the air, the flying reptiles called pterosaurs dominated. One pterosaur, Quetzalcoatlus, from the latest Cretaceous of what is now Texas (U.S.), had a wingspan of about 15 metres (49 feet). Birds developed from a reptilian ancestor during the Jurassic and Cretaceous. Hesperornis was a Cretaceous genus of flightless diving bird that had large feet and sharp backward-directed teeth adapted for preying on fish.

The land plants of the Early Cretaceous were similar to those of the Jurassic. They included the cycads, ginkgoes, conifers, and ferns. The angiosperms appeared in the Early Cretaceous, became common by the beginning of the middle of the Cretaceous, and came to represent the major component of the landscape by the mid-Late Cretaceous. This flora included figs, magnolias, poplars, willows, sycamores, and herbaceous plants. With the advent of many new plant types, insects also diversified.

As mentioned in chapter 1, at or very close to the end of the Cretaceous Period, many animals that were important elements of the Mesozoic world became extinct. On land the dinosaurs perished, but plant life was less affected. Of the planktonic marine flora and fauna, only about 13 percent of the coccolithophore and planktonic foraminiferan genera survived the extinction. Ammonites and belemnites became extinct, as did such marine reptiles as ichthyosaurs, mosasaurs, and plesiosaurs. Among the marine benthos, the larger foraminiferans (orbitoids) died out, and the hermatypic corals were reduced to about one-fifth of their genera. Rudist bivalves disappeared, as did bivalves with a reclining life habit, such as Exogyra and Gryphaea. The stratigraphically important inoceramids also died out. Overall, approximately 80 percent of animal species disappeared, making this one of the largest mass extinctions in Earth’s history.

Many theories have been proposed to explain the Late Cretaceous mass extinction. Since the early 1980s, much attention has been focused on the asteroid theory formulated by American scientists Walter and Luis Alvarez. This theory states that the impact of an asteroid on the Earth may have triggered the extinction event by ejecting a huge quantity of rock debris into the atmosphere, enshrouding the Earth in darkness for several months or longer. With no sunlight able to penetrate this global dust cloud, photosynthesis ceased, resulting in the death of green plants and the disruption of the food chain. There is much evidence in the rock record that supports this hypothesis. A huge crater 180 km (112 miles) in diameter dating to the latest Cretaceous has been discovered buried beneath sediments of the Yucatán Peninsula near Chicxulub, Mexico. In addition, tektites (fractured sand grains characteristic of meteorite impacts) and the rare-earth element iridium, which is common only deep within the Earth’s mantle and in extraterrestrial rocks, have been found in deposits associated with the extinction. There is also evidence for some spectacular side effects of this impact, including an enormous tsunami that washed up on the shores of the Gulf of Mexico and widespread wildfires triggered by a fireball from the impact.

The asteroid theory has met with skepticism among paleontologists who prefer to look to terrestrial factors as the cause of the extinction. A huge outpouring of lava, known as the Deccan Traps, occurred in India during the latest Cretaceous. Some paleontologists believe that the carbon dioxide that accompanied these flows created a global greenhouse effect that greatly warmed the planet. Others note that tectonic plate movements caused a major rearrangement of the world’s landmasses, particularly during the latter part of the Cretaceous. The climatic changes resulting from such continental drift could have caused a gradual deterioration of habitats favourable to the dinosaurs and other animal groups that suffered extinction. It is, of course, possible that sudden catastrophic phenomena such as an asteroid impact contributed to an environmental deterioration already brought about by terrestrial causes.

Dinosaurs continued to evolve throughout the Cretaceous time. Several feathered, horned, and armoured types lived during the period, some with very specialized features. Fossils of several predatory genera, including Albertosaurus and Velociraptor also appear in Cretaceous rocks. During the second half of the period, the hadrosaurs (duck-billed dinosaurs), such as Anatosaurus, Lambeosaurus, and Maiasaura, became the most abundant dinosaurs in North America.

Albertosaurus, formerly known as Gorgosaurus, is a genus of large carnivorous dinosaurs of the Late Cretaceous Period found as fossils in North America and eastern Asia. Albertosaurs are an early subgroup of tyrannosaurs, which appear to have evolved from them.

In structure and presumed habits, Albertosaurus was similar to Tyrannosaurus in many respects. Both had reduced forelimbs and a large skull and jaws, although Albertosaurus was somewhat smaller. Albertosaurus was about 9 metres (30 feet) long, and the head was held 3.5 metres (11.5 feet) off the ground. The hands were similar to those of tyrannosaurs in being reduced to the first two fingers and a mere rudiment of the third. The jaws of Albertosaurus possessed numerous large, sharp teeth, which were recurved and serrated As in tyrannosaurs, the teeth were larger and fewer than in other carnivorous dinosaurs, and, rather than being flattened and bladelike in cross-section, the teeth were nearly round—an efficient shape for puncturing flesh and bone. Like nearly all large carnivores, it is possible that Albertosaurus was at least in part a scavenger, feeding upon dead or dying carcasses of other reptiles or scaring other predators away from their kills.

Albertosaurus fossils occur in rocks that are slightly older than those containing Tyrannosaurus fossils. It is thought that albertosaurs and tyrannosaurs evolved in eastern Asia because the oldest fossils are found in China and Mongolia. According to this view, albertosaurs migrated from Asia to North America, where they became the dominant carnivores of the Late Cretaceous.

Formerly known as Trachodon, this genus of bipedal duckbilled dinosaurs (hadrosaurs) of the Late Cretaceous Period is commonly found as fossils in North American rocks 70 million to about 66 million years old. Related forms such as Edmontosaurus and Shantungosaurus have been found elsewhere in the Northern Hemisphere.

Anatosaurus grew to a length of 9–12 metres (30–40 feet) and was heavily built. The skull was long and the beak broad and flat, much like a duck’s bill. As in all iguanodontids and hadrosaurs, there were no teeth in the beak itself, which was covered by a horny sheath. However, several hundred rather blunt teeth were arranged in rows along the sides of the cheeks at any given time. There were dozens of teeth along each row, and several rows of exposed and partially worn replacement teeth were present behind the outer teeth. Not all were functional simultaneously, but, as teeth became worn or lost, they were replaced continually by new ones.

Some Anatosaurus specimens have been found desiccated and remarkably well preserved, with skin and internal structures remaining. Such evidence indicates that the outer hide was leathery and rough. Anatosaurus may have fed mostly on twigs, seeds, fruits, and pine needles, judging from fossilized stomach remains. No digested remains of aquatic plants have been found. The flat, blunt, hooflike claw bones of Anatosaurus and other duckbills suggest that they were much like today’s browsing mammals in their habits, probably traveling in herds and feeding on a variety of land vegetation.

Anatosaurus was a member of the duckbill lineage called hadrosaurines, which, unlike lambeosaurine hadrosaurs, did not evolve elaborate crests on the skull. Trachodon was a name assigned to hadrosaur remains that consisted only of isolated teeth.

This genus of armoured ornithischian dinosaurs lived 70 million to roughly 66 million years ago in North America during the Late Cretaceous Period. Ankylosaurus is a genus belonging to a larger group (infraorder Ankylosauria) of related four-legged, herbivorous, heavily armoured dinosaurs that flourished throughout the Cretaceous Period.

Ankylosaurus was one of the largest ankylosaurs, with a total length of about 10 metres (33 feet) and a probable weight of about four tons. Its head was square, flat, and broader than it was long. Its teeth, like those of the related stegosaurs, consisted of a simple curved row of irregularly edged (crenulated) leaf-shaped teeth. The body was short and squat, with massive legs to support its weight. Like other ankylosaurs, its back and flanks were protected from attack by thick bands of armour consisting of flat bony plates. These plates were supplemented by rows of bony spikes projecting from the animal’s flanks and by bony knobs on its back. The skull was also heavily armoured and spiked. Ankylosaurus’s long tail terminated in a thick “club” of bone, which it probably swung as a defense against predators. This club was formed by the last tail vertebrae, which were nested tightly against each other and a sheath of several bony plates. The armour schemes of other ankylosaurs varied somewhat, but all were well protected against attack by carnivorous dinosaurs. The earliest ankylosaurs, called nodosaurs, lacked the tail club and had rather different armour patterns.

Caudipteryx, an early Cretaceous dinosaur thought to be one of the first known dinosaurs with feathers. Encyclopædia Britannica, Inc.

This genus of small feathered theropod dinosaurs is known from rock deposits of western Liaoning province, China, that date from about 125 million years ago, during the Early Cretaceous. Caudipteryx was one of the first-known feathered dinosaurs. Fossil specimens have impressions of long feathers on the forearms and tail. These feathers were symmetrical and similar to those of living flightless birds. However, they differed from those of living and fossil flying birds, such as Archaeopteryx. Furthermore, the forelimbs of Caudipteryx were too short to have functioned as wings, suggesting that complex feathers originally evolved in nonflying animals for purposes other than flight.

With its small head, long neck, compact body, and fan of tail feathers, Caudipteryx probably resembled a small pheasant or turkey, and it may have occupied a similar ecological niche. In members of this genus, teeth were present on the premaxillae (the bones at the front of the upper jaw). However, the maxillae and the lower jaws were toothless and presumably beaked. Furthermore, numerous gastroliths (stomach stones) were found in the rib cages of some specimens. These probably functioned as a gastric mill for grinding up tough forage, such as plant material and the chitinous exoskeletons of insects, as in the muscular gizzards of many birds.

Caudipteryx was a primitive member of Oviraptorosauria, a group of theropods that were closely related to birds. Oviraptorosaurs differed from most other theropods in having a deep belly and a short, stiff tail. In addition, many forms had few, if any, teeth. According to some authorities, the reduced dentition and deep abdomen may have been adaptations for herbivory. Some oviraptorosaurs, however, possessed significant numbers of teeth, and these forms may have been omnivorous or insectivorous.

This long-clawed carnivorous dinosaur flourished in western North America during the Early Cretaceous Period. A member of the dromaeosaur group, Deinonychus was bipedal, walking on two legs, as did all theropod dinosaurs. Its principal killing devices were large sicklelike talons 13 cm (5 inches) long on the second toe of each foot. The slender, outstretched tail was enclosed in bundles of bony rods. These extensions of the tail vertebrae were ideal for helping the animal maintain balance as it ran or attacked prey.

Deinonychus was the model for the “raptor” dinosaurs of the motion picture Jurassic Park (1993). The name raptor has come to apply to dromaeosaurs in general as a contraction for Velociraptor, a genus of dromaeosaur that was considerably smaller than Deinonychus. However, the term raptor (from the Greek word for “seize” or “grab”) is more correctly applied to birds such as hawks and eagles, which grasp prey with their talons. Deinonychus measured about 2.5 metres (8 feet) or perhaps more in length and weighed 45–68 kg (100–150 pounds). It was evidently a fast, agile predator whose large brain enabled it to perform relatively complex movements during the chase and kill.

Dromaeosaurs and troodontids are the closest known relatives of Archaeopteryx and existing birds. These dinosaurs share with birds a number of features, including unusually long arms and hands and a wrist that is able to flex sideways. Such adaptations apparently helped these dinosaurs to grasp prey and later enabled birds to generate an effective flight stroke.

A genus of small feathered theropod dinosaurs, Dilong is known from rock deposits of western Liaoning province, China, that date from 128 million to 127 million years ago, during the Early Cretaceous. Dilong was one of the most primitive known tyrannosaurs, a group that includes Tyrannosaurus and other similar dinosaurs, and the first tyrannosauroid discovered with feathers. Dilong was comparatively small, with a total length of 1.6 metres (about 5 feet) and an estimated mass of 5 kg (about 11 pounds). Dilong differs from Tyrannosaurus in having proportionally larger forelimbs and three-fingered, grasping hands. It also shared many advanced features of the skull with later tyrannosaurs—such as fused nasal bones, extensive sinuses, and a rounded snout with anterior teeth that are D-shaped in cross section. This pattern of anterior teeth gave the animal a “cookie-cutter” bite when hunting or consuming prey. In most other aspects of its anatomy, Dilong resembled juveniles of larger and later tyrannosaurs. The existence of Dilong demonstrates that tyrannosaurs were anatomically distinctive before they evolved into gigantic predators.

Dilong paradoxus, an early Cretaceous dinosaur that is one of the more primitive tyrannosaurs. Encyclopædia Britannica, Inc.

Dilong was the first primitive tyrannosaur known from reasonably complete remains. One of the fossil specimens includes impressions of protofeathers. This is the first evidence that, like many other coelurosaurs (that is, theropod dinosaurs closely related to birds), tyrannosaurs were feathered. The protofeathers were made up of branched filaments that extended to 2 cm (0.8 inch) long, but these filaments would have resembled a coat of hair rather than the contour feathers of birds. Dilong and most other feathered coelurosaurs could not fly and were not descended from flying animals. This evidence suggests that feathers first evolved as insulation and only later were co-opted for flight.

The dromaeosaurs (family Dromaeosauridae) are a group of small to medium-sized carnivorous dinosaurs that flourished in Asia and North America during the Cretaceous Period. Agile, lightly built, and fast-running, these theropods were among the most effective predators of their time.

All dromaeosaurs were bipedal, and the second toe of each foot was extremely flexible and bore a specialized killing claw, or talon, that was not used in walking. Instead, it was always held off the ground because it was much larger and was jointed differently from the other claws. The largest killing claw belonged to Deinonychus and measured up to 13 cm (5 inches) in length.

Dromaeosaurs had large heads equipped with many sharp serrated teeth, and their long arms ended in slender three-clawed hands that were used for grasping. Like troodontids and birds, dromaeosaurs had a unique wrist joint that allowed the hands to flex sideways. This evidently helped them seize their prey. In birds the same motion produces the flight stroke. The tails of dromaeosaurs were also unusually long and were somewhat stiffened by bundles of slim bony rods that were extensions of the arches of the tail vertebrae.

Dromaeosaurs apparently ran down their prey (probably small- to medium-sized herbivores), seizing it with the front claws while delivering slashing kicks from one of the taloned hind legs. In doing so, dromaeosaurs may have been able to hold this one-footed pose by using the rigidly outstretched tail as a counterbalance, or they may have attacked by using both feet in a single leaping action. The relatively large brains of dromaeosaurs enabled them to carry out these complex movements with a degree of coordination unusual among reptiles but quite expected in these closest relatives of birds.

Fossil evidence supporting the prediction of grasping arms and slashing foot claws was borne out by the discovery in the 1970s of a Velociraptor preserved in a death position with a small ceratopsian dinosaur, Protoceratops. The hands of Velociraptor were clutching the frill of Protoceratops, and the large foot claw was found embedded in its throat.

Utahraptor was considerably larger than Deinonychus but is incompletely known. Dromaeosaurus and Velociraptor both reached a length of about 1.8 metres (6 feet). There is debate as to whether Microraptor, the smallest and most birdlike dinosaur known, is a dromaeosaur or a troodontid. Only about the size of a crow, Microraptor appears to have possessed feathers. The single specimen was discovered in China in 2000 from deposits dating to the Early Cretaceous.

This armoured dinosaur inhabited North America during the Late Cretaceous Period. Like its close relative Ankylosaurus and the more distantly related Nodosaurus, Euoplocephalus was a massive animal that likely weighed more than two tons. Euoplocephalus differed from these and most other ankylosaurs in having a bone that protected the eyelid. The teeth, as in all ankylosaurs, were limited to a single curved row and were used to eat plants.

Hesperornis is a genus of extinct birds found as fossils in Late Cretaceous Period deposits dating from about 120 million to 66 million years ago. This bird is known mostly from the Great Plains region of the United States, but some remains have been found as far north as Alaska. Hesperornis was primitive in that teeth were present in the lower jaw. The rear portion of the upper jaw also had teeth. This evidence suggests that the horny beak characteristic of today’s birds had not yet evolved in Hesperornis.

Hesperornis was clearly an actively swimming bird that probably chased and caught fish. Although unrelated to today’s loons (order Gaviiformes), many of Hesperornis’s skeletal features resembled those of loons, and, like loons, Hesperornis is thought to have been a good diver. The wings were small and useless for flight, and the wing bones were splintlike. The breastbone lacked the prominent keel that serves as an anchor for powering flight muscles. The legs, however, were powerfully developed and clearly adapted for rapid diving and swimming through water. The neck was slender and the head long and tapered. Both were probably capable of rapid side-to-side movement

A genus of small to medium-sized herbivorous dinosaurs that flourished about 115 million to 110 million years ago during the Early Cretaceous Period, Hypsilophodon was up to 2 metres (6.5 feet) long and weighed about 60 kg (130 pounds). It had short arms with five fingers on each hand and was equipped with much longer four-toed hind feet. In its mouth was a set of high, grooved, self-sharpening cheek teeth adapted for grinding up plant matter. In its horny beak were several incisor-like teeth used to nip off vegetation.

For many decades paleontologists thought that Hypsilophodon’s long fingers and toes enabled it to live in trees, but this inference was based on an incorrect reconstruction of its hind foot, which suggested it could grasp and perch. The dinosaur is now recognized to have been a ground dweller with a conventional ornithopod foot. Hypsilophodon is typical of a lineage of ornithopods known as Hypsilophodontidae. Two other major groups of ornithopods—the hadrosaurs, or duck-billed dinosaurs, and the iguanodontids—are closely related. Hypsilophodontids survived into the Late Cretaceous, when they lived alongside the iguanodontids and hadrosaurs that probably arose from early members of the lineage.

Ichthyornis, a genus of extinct seabirds from the Late Cretaceous, occur as fossils in the U.S. states of Wyoming, Kansas, and Texas. Ichthyornis somewhat resembled present-day gulls and terns and may even have had webbed feet. The resemblance, however, is superficial, because Ichthyornis and its relatives lacked many features that all the living groups of birds have.

Ichthyornis was about the size of a domestic pigeon and had strongly developed wings. The breastbone was large, with a strong keel, and the wing bones were long and well developed. The shoulder girdle was similar to that of strong-flying birds of the present. The legs were strong, with short shanks, long front toes, and a small, slightly elevated hind toe. The tail had a well-developed terminal knob made of several fused vertebrae (pygostyle), as did the tails of all but the most primitive birds such as Archaeopteryx. Indications are that Ichthyornis, like its modern relatives, lacked teeth. The brain of Ichthyornis showed greater development than that of another Cretaceous seabird, Hesperornis, but its brain was still smaller than that of modern birds. Other traits of Ichthyornis are not known for certain, as the known fossil material is fragmentary and the association of some of the bones is in question. Some portions may turn out to belong to other kinds of Cretaceous birds.

Because it was once thought to have had teeth, Ichthyornis was formerly grouped with Hesperornis, but it is now classified as the sole genus of the order Ichthyornithiformes. Ichthyornis was one of the notable discoveries of the American paleontologist Othniel Charles Marsh.

This duck-billed dinosaur (hadrosaur) is notable for the hatchet-shaped hollow bony crest on top of its skull. Fossils of this herbivore date to the Late Cretaceous Period of North America. Lambeosaurus was first discovered in 1914 in the Oldman Formation, Alberta, Canada. These specimens measured about 9 metres (30 feet) long, but larger specimens up to 16.5 metres (54 feet) in length have been found recently in Baja California, Mexico. Lambeosaurus and related genera are members of the hadrosaur subgroup, Lambeosaurinae.

Several lambeosaurines possessed a range of bizarre cranial crests, and various functions for these crests have been proposed. For example, it has been suggested that the complex chamber extensions of the breathing passage between the nostrils and the trachea contained in the crest served as resonating chambers for producing sound or as expanded olfactory membranes to improve the sense of smell. Other proposed functions such as air storage, snorkeling, or combat have been dismissed for various reasons. No single function or suite of functions appears to fit all lambeosaurine crests, and it is possible that their strange shapes were mainly features by which members of different species recognized each other from members of other species. As in all other duck-billed dinosaurs, the dentition was expanded and adapted for chewing large quantities of harsh plant tissues.

Lambeosaurinae and Hadrosaurinae are the two major lineages of the duck-billed dinosaur family, Hadrosauridae. Members of the two subgroups are distinguished by the presence or absence of cranial crests and ornamentation and by the shape of the pelvic bones.

Maiasaura, a genus of duck-billed dinosaurs (hadrosaurs), appear as fossils from the Late Cretaceous of North America. The discovery of Maiasaura fossils led to the theory that this group of bipedal herbivores cared for their young.

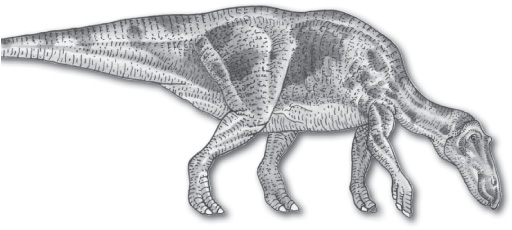

Maiasaura, a Late Cretaceous herbivore. Dorling Kindersley/Getty Images

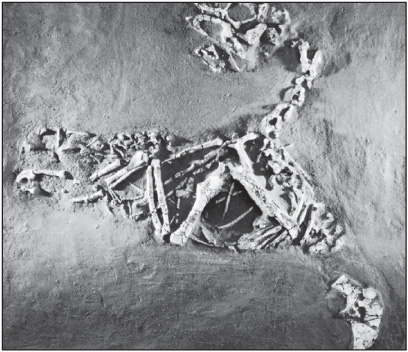

In 1978 a Maiasaura nesting site was discovered in the Two Medicine Formation near Choteau, Montana, U.S. The remains of an adult Maiasaura were found in close association with a nest of juvenile dinosaurs, each about 1 metre (3.3 feet) long. Hatchlings that were too large (about 0.5 metre long) to fit into eggs, and nests with clutches of eggs, as well as many broken eggshells, were found nearby. The bones of the embryos, however, were not fully ossified, which means the young could not have walked immediately upon hatching and would have required some degree of parental care. Hundreds of skeletons preserved in one specific ashbed in Montana, as well as those preserved in nesting sites, suggest that Maiasaura was migratory. Such evidence also demonstrates that these dinosaurs were social animals that nested in groups. They probably returned to the same nesting site year after year. Studies of bone structure indicate that it would have taken about seven or eight years for Maiasaura to reach an adult size of 8 metres (26 feet).

Nodosaurus is a genus of armoured dinosaurs found as fossils in North America dating from 95 million to 90 million years ago during the Late Cretaceous Period. A heavy animal about 5.5 metres (18 feet) long, Nodosaurus had a long tail but a very small head and a minuscule brain. For protection against predators, it relied upon a heavy coat of thick bony plates and knobs that covered its back. The front legs were much smaller than the hind legs, and the back was strongly arched.

Nodosaurids (family Nodosauridae) and ankylosaurids (family Ankylosauridae) are the two commonly recognized groups within Ankylosauria, the armoured dinosaurs. Of the two subgroups, nodosaurids are generally regarded as more primitive, having generally lived before the ankylosaurids (nearly all of which date from the Late Cretaceous). Nodosaurid ancestors of Nodosaurus are first found in Middle Jurassic deposits of Europe, though they are mostly known from the Early Cretaceous, and some survived to the end of the period. Nodosaurids lacked the tail club of ankylosaurids, and their skulls were generally not as short or broad, nor was the skull covered with protective plates (scutes).

This genus of ostrichlike dinosaurs is known from fossils in Mongolian, European, and North American deposits dating from 125 million to 66 million years ago.

Ornithomimus was about 3.5 metres (11.5 feet) long, and, although it was a theropod dinosaur, it was likely omnivorous. Its name means “bird mimic,” and, like most other members of its subgroup (Ornithomimidae), it was toothless and had beaklike jaws. The small, thin-boned skull had a large brain cavity. Its three fingers were unusual among dinosaurs in that they were all approximately the same length. Ornithomimus’s legs were very long, especially its foot bones (metatarsals). The legs and feet, along with its toothless beak and long neck, provide a superficial resemblance to the living ostrich. A related ornithomimid is so ostrichlike that its name means “ostrich-mimic” Ornithomimidae also includes small forms such as Pelecanimimus, larger ones such as Garudimimus and Harpymimus, and the giant Deinocheirus, known only from a 2.5-metre (8-foot) shoulder girdle and forelimb from the Late Cretaceous of Mongolia.

This group of small, lightly built predatory or omnivorous dinosaurs brooded its eggs in a manner similar to birds. Found as fossils in deposits from the Late Cretaceous Period of eastern Asia and North America, Oviraptor was about 1.8 metres (6 feet) long and walked on two long, well-developed hind limbs. The forelimbs were long and slender, with three long clawed fingers clearly suited for grasping, ripping, and tearing. Oviraptor had a short skull with very large eyes surrounded by a bony ring, and it was possibly capable of stereoscopic vision. The skull also had strange cranial crests, and the jaws lacked teeth but were probably sheathed with a horny, beaklike covering.

Oviraptor philoceratops, from Djadochta Cretaceous beds, Shabarkh Uso, Mongolia. Courtesy of the American Museum of Natural History, New York

Oviraptor is named from the Latin terms for “egg” and “robber,” because it was first found with the remains of eggs that were thought to belong to Protoceratops, an early horned dinosaur. However, microscopic studies of the eggshells have shown that they were not ceratopsian but theropod. Later, several other Oviraptor skeletons were found atop nests of eggs in a brooding position exactly like that of living birds.

This genus of large and unusual dinosaurs are known from fossils in North American deposits dating to the Late Cretaceous Epoch. Pachycephalosaurus, which grew to be about 5 metres (16 feet) long, was a biped with strong hind limbs and much less developed forelimbs. The unusual and distinctive feature of Pachycephalosaurus is the high, domelike skull formed by a thick mass of solid bone grown over the tiny brain. This bone growth covered the temporal openings that were characteristic of the skulls of related forms. Abundant bony knobs in front and at the sides of the skull further added to the unusual appearance. Pachycephalosaurus and closely related forms are known as the bone-headed, or dome-headed, dinosaurs. These dinosaurs, which are also found in Mongolia, had a variety of skull shapes. In the most basal forms, the dome was not thick but flat. Late forms had thick domes shaped like kneecaps, or a large sagittal crest with spikes and knobs pointing down and back from the sides of the skull. It has been suggested that these animals were head butters like living rams, but the configuration of the domes does not support this hypothesis. Flank-butting remains a possibility in some species, but a more likely function in most was species recognition or display.

Pachyrhinosaurus is a genus of horned ceratopsid dinosaurs that roamed northwestern North America from 71 million to 67 million years ago. It is closely related to Styracosaurus and Centrosaurus and more distantly related to Triceratops. Like other ceratopsids, it possessed a prominent skull characterized by a narrow but massive beak and a bony frill. The Greek name Pachyrhinosaurus means “reptile with a thick nose.”

Pachyrhinosaurus was both large and quadrupedal. It grew to 6 metres (20 feet) in length and weighed about 1,800 kg (almost 2 tons). A herbivore, Pachyrhinosaurus used the batteries of teeth in its jaws to slice open and consume plants. Some of its horns grew in unicorn fashion between and slightly behind the eyes, whereas others decorated the top edge of the frill. Pachyrhinosaurus also sported thickened knobs of bone. The largest of these knobs covered the top of the nose. The function of these knobs, horns, and frill is unknown, but they may have been used for species recognition, competition between males, or defense against predators.

Specimens of Pachyrhinosaurus are known from bone beds in southern Alberta, Can., and the North Slope of Alaska, U.S. In both locations, the bone beds contain juveniles and adults, which suggests that this dinosaur may have provided parental care by herding. Although average global temperatures were much warmer during the Cretaceous Period than they are today, Pachyrhinosaurus populations in Alaska and northern Canada did have to contend with months of winter darkness. It remains unknown whether they migrated south during the Alaskan winter.

Specimens of this five-horned herbivorous dinosaur have been found as fossils in North America and possibly eastern Asia dating from the Late Cretaceous Period. Pentaceratops was about 6 metres (20 feet) long and had one horn on its snout, one above each eye, and one on each side of the large bony neck frill. It was a ceratopsian related to the more familiar Triceratops and is especially well known from the Kirtland Shale of New Mexico, U.S.

Fossils of this ceratopsian dinosaur were discovered in the Gobi Desert from 80-million-year-old deposits of the Late Cretaceous Period. Protoceratops was a predecessor of the more familiar horned dinosaurs such as Triceratops. Like other ceratopsians, it had a rostral bone on the upper beak and a small frill around the neck, but Protoceratops lacked the large nose and eye horns of more derived ceratopsians.

Protoceratops evolved from small bipedal ceratopsians such as Psittacosaurus, but Protoceratops was larger and moved about on all four limbs. The hind limbs, however, were more strongly developed than the forelimbs (as expected in an animal that evolved from bipedal ancestors), which gave the back a pronounced arch. Although small for a ceratopsian, Protoceratops was still a relatively large animal. Adults were about 1.8 metres (6 feet) long and would have weighed about 180 kg (400 pounds). The skull was very long, about one-fifth the total body length. Bones in the skull grew backward into a perforated frill. The jaws were beaklike, and teeth were present in both the upper and lower jaws. An area on top of the snout just in front of the eyes may mark the position of a small hornlike structure in adults.

The remains of hundreds of individuals have been found in all stages of growth. This unusually complete series of fossils has made it possible to work out the rates and manner of growth of Protoceratops and to study the range of variation evident within the genus. Included among Protoceratops remains are newly hatched young. Ellipsoidal eggs laid in circular clusters and measuring about 15 cm (6 inches) long were once attributed to Protoceratops, but they are now known to belong to the small carnivorous dinosaur Oviraptor.

Psittacosaurus is a primitive member of the horned dinosaurs (Ceratopsia) found as fossils dating from 122 million to 100 million years ago in Early Cretaceous deposits of Mongolia and China.

Psittacosaurus measured about 2 metres (6.5 feet) long and was probably bipedal most of the time. The skull was high and narrow and is characterized by a small bone (rostral) that forms the upper beak. The anterior region of the skull was shaped very much like a parrot’s beak in that the upper jaw curved over the lower, hence the dinosaur’s name (“psittac” being derived from the Latin term for “parrot”). Apart from these unusual features, Psittacosaurus appears likely to have evolved from bipedal ornithopod dinosaurs sometime in the Late Jurassic or very Early Cretaceous.

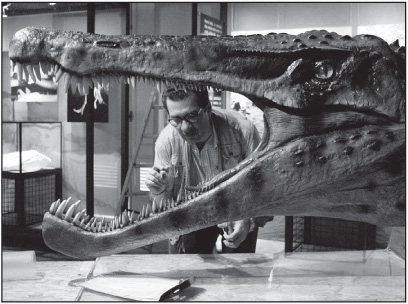

This genus of theropod dinosaurs is known from incomplete North African fossils that date to Cenomanian times (roughly 100 to 94 million years ago). Spinosaurus, or “spined reptile,” was named for its “sail-back” feature, created by tall vertebral spines. It was named by German paleontologist Ernst Stromer in 1915 on the basis of the discovery of a partial skeleton from Bahariya Oasis in western Egypt by his assistant Richard Markgraf. These fossils were destroyed in April 1944 when British aircraft inadvertently bombed the museum in Munich in which they were housed. For several decades Spinosaurus was known only from Stromer’s monographic descriptions. However, additional fragmentary remains were discovered during the 1990s and 2000s in Algeria, Morocco, and Tunisia. Related taxa in the family Spinosauridae include Baryonyx from England, Irritator from Brazil, and Suchomimus from Niger.

A specialist retouches the reconstructed head of a Spinosaurus, which resembles that of a crocodile. Vanderlei Almeida/AFP/Getty Images

Spinosaurus, which was longer and heavier than Tyrannosaurus, is the largest known carnivorous dinosaur. It possessed a skull 1.75 metres (roughly 6 feet) long, a body length of 14–18 metres (46–59 feet), and an estimated mass of 12,000–20,000 kg (13–22 tons).

Like other spinosaurids, Spinosaurus possessed a long, narrow skull resembling that of a crocodile and nostrils near the eyes instead of the end of the snout. Its teeth were straight and conical instead of curved and bladelike as in other theropods. All of these features are adaptations for piscivory (that is, the consumption of fish). Other spinosaurids have been found with partially digested fish scales and the bones of other dinosaurs in their stomach regions, and spinosaurid teeth have been found embedded in pterosaur bones. The sail over the animal’s back was probably used for social displays or species recognition rather than for temperature regulation. Some authorities maintain that the sail was actually a hump used to store water and lipids.

Struthiomimus is a genus of ostrichlike dinosaurs found as fossils from the Late Cretaceous Period in North America. Struthiomimus (meaning “ostrich mimic”) was about 2.5 metres (8 feet) long and was obviously adapted for rapid movement on strong, well-developed hind limbs. The three-toed feet were especially birdlike in that they had exceedingly long metatarsals (foot bones), which, as in birds (and some other dinosaurs), did not touch the ground. Struthiomimus had a small, light, and toothless skull perched atop a slender and very flexible neck. The jaws were probably covered by a rather birdlike horny beak. The forelimbs were also long and slender, terminating in three-fingered hands with sharp claws adapted for grasping. The hand, as in all members of the theropod subgroup Ornithomimidae, is diagnostic in that all three fingers are nearly the same length.

This group of theropod dinosaurs lived during the Late Cretaceous in Asia and North America and were characterized by their relatively small skulls, leaf-shaped teeth, and extended fingers with extremely long and robust claws. Therizinosaurs also lacked teeth in the front half of their upper jaws, and they had long necks, wrist bones similar to those of birds, widely spaced hips, a backward-pointing pubis bone, and four widely spread toes similar to those of sauropod dinosaurs. Fossil specimens have been known since the 1950s, but their unusual combination of skeletal features (especially their teeth, hips, and toes) made their relationships to other dinosaur groups contentious. By the mid-1990s, the discovery of new, more complete specimens had confirmed their theropod ancestry. Therizinosaurs are divided into five genera (Beipiaosaurus, Falcarius, Alxasaurus, Erlikosaurus, and Therizinosaurus).

Unlike most other theropods, therizinosaurs were most likely herbivorous. It is likely that the transition from carnivory to herbivory occurred early in the evolution of the group. The transition involved changes in dentition and changes to the hips and hind limbs—which allowed more room and better support for the larger gut needed to digest plants. The most primitive therizinosaur, Falcarius, has been described as a transitional species because it has herbivorous dentition and wider hips. However, it also possessed a pubis bone and legs that resembled those of its running, carnivorous ancestors.

Some therizinosaur fossils show remarkable preservation. For example, Beipiaosaurus specimens show large patches of featherlike integument on the chest, forelimbs, and hind limbs. Several embryonic therizinosaur skeletons have been found inside fossilized eggs. These embryos show several unambiguous theropod characteristics that are lost by adulthood. They provide insight into the order of bone formation in dinosaurs.

Triceratops is a genus of large plant-eating dinosaurs characterized by a great bony head frill and three horns. Its fossils date to only the last 5 million years of the Late Cretaceous Period, which makes Triceratops one of the last of the dinosaurs to have evolved.

The massive body measured nearly 9 metres (30 feet) long and must have weighed four to five tons, and the skull alone was sometimes more than 2 metres (6.5 feet) long. Each of the two horns above the eyes was longer than 1 metre (3.3 feet). The frill, unlike that of other ceratopsians, was made completely of solid bone, without the large openings typically seen in ceratopsian frills. The front of the mouth was beaklike and probably effective for nipping off vegetation. The cheek teeth were arranged in powerful groups that could effectively grind plant matter. The hind limbs were larger than the forelimbs, but both sets were very stout. The feet ended in stubby toes probably covered by small hooves. Triceratops was an upland, browsing animal that may have traveled in groups or small herds.

A sickle-clawed dinosaur that flourished in central and eastern Asia during the Late Cretaceous Period, Velociraptor is closely related to the North American Deinonychus of the Early Cretaceous. Both reptiles were dromaeosaurs, and both possessed an unusually large claw on each foot, as well as ossified tendon reinforcements in the tail that enabled them to maintain balance while striking and slashing at prey with one foot upraised. Velociraptor was smaller than Deinonychus, reaching a length of only 1.8 metres (6 feet) and perhaps weighing no more than 45 kg (100 pounds). Velociraptor appears to have been a swift, agile predator of small herbivores.

Several notable molluscan and mammalian groups lived during the Cretaceous Period.

This genus of extinct marine gastropods (snails) appears as fossils only in marine deposits of Cretaceous age. It is thus a useful guide or index fossil because it is easily recognizable. The shell whorls are globular and ornamented with raised crenulations; the spire is sharply pointed; the body whorl, the final and largest whorl, has a prominently extended outer lip.

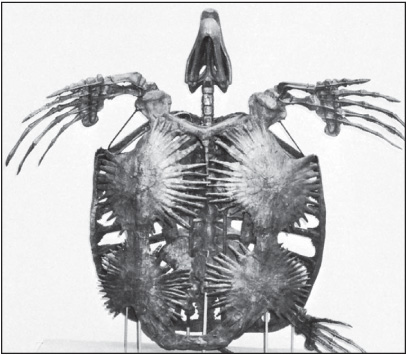

An extinct genus of giant sea turtle known from fossilized remains found in North American rocks of the Late Cretaceous epoch, Archelon was protected by a shell similar to that found in modern sea turtles, and reached a length of about 3.5 metres (12 feet). The front feet evolved into powerful structures that could efficiently propel the great bulk of Archelon through the water.

This genus of extinct cephalopods (animals related to the modern squid, octopus, and nautilus) found as fossils in Late Cretaceous marine rocks. Baculites, restricted to a narrow time range, is an excellent guide or index fossil for Late Cretaceous time and rocks. The distinctive shell begins with a tightly coiled portion that becomes straight in form, with a complex, ammonite sutural pattern.

Skeleton of the Cretaceous marine turtle Archelon, length 3.25 metres (10.7 feet). Courtesy of the Peabody Museum of Natural History, Yale University

Clidastes is an extinct genus of ancient marine lizards belonging to a family of reptiles called mosasaurs. Clidastes fossils are found in marine rocks from the Late Cretaceous Period in North America. Excellent specimens have been found in the chalk deposits of Kansas.

Clidastes was 4 metres (13 feet) or longer. The head alone was about 60 cm (24 inches) long and was equipped with many sharply pointed curved teeth. The neck was short, but the body and tail were long and relatively slender. This aquatic lizard probably swam by undulating its body in the same way that terrestrial lizards do. The limbs terminated in broad appendages that provided directional control as it moved through the water. Clidastes was clearly an efficiently swimming predator and probably fed mostly on fish as well as on ammonoids (a cephalopod similar to the present-day nautilus). Clidastes and other mosasaurs may have gone ashore to reproduce.

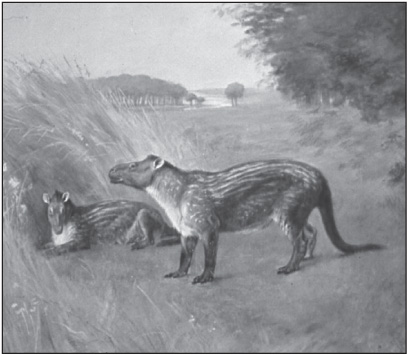

This extinct group of mammals includes the ancestral forms of later, more advanced ungulates (that is, hoofed placental mammals). The name Condylarthra was once applied to a formal taxonomic order, but it is now used informally to refer to ungulates of Late Cretaceous and Early Paleogene times. Their greatest diversity occurred during the Paleocene Epoch (65.5 million to 55.8 million years ago), but similar forms persisted into the middle of Oligocene Epoch and died out about 30 million years ago.

Condylarths appear to have originated in Asia during the Cretaceous Period. The earliest condylarths were the zhelestids, rodent-sized ungulates from the Late Cretaceous of Uzbekistan. A somewhat later North American form is the genus Protungulatum that lived near the end of Cretaceous or early in the Paleocene.

The condylarths were a diverse group that developed many traits of adaptive significance. They are thought to be the ancestors of the perissodactyls and perhaps even the cetaceans. Some forms remained relatively small, whereas others attained large size. Phenacodus, a well-known condylarth from the Eocene Epoch (55.8 million to 33.9 million years ago), grew to be as large as a modern tapir. In addition, the teeth of some condylarths appear almost carnivore-like. Arctocyon, for example, has long canines and triangular premolars.

Phenacodus, restoration painting by Charles R. Knight, 1898 Courtesy of the American Museum of Natural History, New York

This genus of conifers represented by a single living species, Metasequoia glyptostroboides, from central China. Fossil representatives, such as M. occidentalis, dated to about 90 million years ago during the Late Cretaceous Period, are known throughout the middle and high latitudes of the Northern Hemisphere. Climatic cooling and drying that began about 65.5 million years ago and continued throughout the Cenozoic Era caused the geographic range of the dawn redwood to contract to its present relic distribution. The leaves are arranged in pairs on deciduous branchlets, and this deciduous character probably accounts for the tree’s abundance in the fossil record. Metasequoia is closely related to the redwood genera of North America, Sequoia and Sequoiadendron.

The dawn redwood holds an interesting place in the history of paleobotany as one of the few living plants known first as a fossil. Its fossil foliage and cones were originally described under the name Sequoia. In 1941, Japanese botanist Miki Shigeru of Osaka University coined the name Metasequoia for fossil foliage with opposite, rather than spirally arranged, leaves. The first living Metasequoia trees were discovered in 1944 by Chinese botanist Wang Zhan in Sichuan province, China. Today, M. glyptostroboides is a common ornamental tree that grows well in temperate climates worldwide.

A genus of extinct mammals found as fossils in rocks from Late Cretaceous times of Asia and, questionably, North America, Deltatheridium was a small insectivorous mammal about the size of a small rat. It is now recognized to be a metatherian, a member of the group of mammals related to marsupials. Deltatheridium has figured prominently in debates about mammalian evolution because it also has some features that are similar to early placental mammals.

This extinct molluscan genus is common in shallow-water marine deposits of the Jurassic and Cretaceous periods. Exogyra is characterized by its very thick shell, which attained massive proportions. The left valve, or shell, is spirally twisted, whereas the right valve is flattish and much smaller. A distinctive longitudinal pattern of ribbing is well developed in the left valve, and pitting is common.

A genus of extinct and unusual bivalves (clams) found as fossils in Cretaceous rocks, Monopleura is representative of a group of aberrant clams known as the pachyodonts. The animal’s thick, triangular shell is capped by a much smaller dome-shaped shell. In some of the pachyodonts, there were open passageways through the shell that allowed for the passage of fluids. Monopleura and other pachyodonts were sedentary in habit. The animal apparently grew upright with the pointed end anchored in the substrate.

These extinct aquatic lizards from family Mosasauridae attained a high degree of adaptation to the marine environment and were distributed worldwide during the Cretaceous Period. The mosasaurs competed with other marine reptiles—the plesiosaurs and ichthyosaurs—for food, which consisted largely of ammonoids, fish, and cuttlefish. Many mosasaurs of the Late Cretaceous were large, exceeding 9 metres (30 feet) in length, but the most common forms were no larger than modern porpoises.

Mosasaurs had snakelike bodies with large skulls and long snouts. Their limbs were modified into paddles having shorter limb bones and more numerous finger and toe bones than those of their ancestors. The tail region of the body was long, and its end was slightly downcurved in a manner similar to that of the early ichthyosaurs. The backbone consisted of more than 100 vertebrae. The structure of the skull was very similar to that of the modern monitor lizards, to which mosasaurs are related. The jaws bore many conical, slightly recurved teeth set in individual sockets. The jawbones are notable in that they were jointed near mid-length (as in some of the advanced monitors) and connected in front by ligaments only. This arrangement enabled the animals not only to open the mouth by lowering the mandible but also to extend the lower jaws sideways while feeding on large prey.

This group of long-necked marine reptiles are known from fossils that date from the Late Triassic Period into the Late Cretaceous Period (215 million to 80 million years ago). Plesiosaurs had a wide distribution in European seas and around the Pacific Ocean, including Australia, North America, and Asia. Some forms known from North America and elsewhere persisted until near the end of the Cretaceous Period.

Plesiosaurus, an early plesiosaur, was about 4.5 metres (15 feet) long, with a broad, flat body and a relatively short tail. It swam by flapping its fins in the water, much as sea lions do today, in a modified style of underwater “flight.” The nostrils were located far back on the head near the eyes. The neck was long and flexible, and the animal may have fed by swinging its head from side to side through schools of fish, capturing prey by using the long, sharp teeth present in the jaws.

Early in their evolutionary history, the plesiosaurs split into two main lineages: the pliosaurs, in which the neck was short and the head elongated; and the plesiosaurids, in which the head remained relatively small and the neck assumed snakelike proportions and became very flexible. The late evolution of plesiosaurs was marked by a great increase in size. For example, Elasmosaurus, a plesiosaurid, had as many as 76 vertebrae in its neck alone and reached a length of about 13 metres (43 feet), fully half of which consisted of the head and neck.

These flying reptiles (pterosaurs) are known from fossils in North American deposits that date from about 100 million to 90 million years ago during the Late Cretaceous Period. Pteranodon had a wingspan of 7 metres (23 feet) or more, and its toothless jaws were very long and pelican-like.

Drawing of a Pteranodon. Encyclopædia Britannica, Inc.

A crest at the back of the skull (a common feature among pterosaurs) may have functioned in species recognition. The crest of males was larger. The crest is often thought to have counterbalanced the jaws or have been necessary for steering in flight, but several pterosaurs had no crests at all. As compared with the size of the wings, the body was small (about as large as a turkey), but the hind limbs were relatively large compared with the torso. Although the limbs appear robust, the bones were completely hollow, and their walls were no thicker than about one millimetre. The shape of the bones, however, made them resistant to the aerodynamic forces of flight Pteranodon, like other pterosaurs, was a strong flier with a large breastbone, reinforced shoulder girdles, and muscular attachments on the arm bones—all evidence of power and maneuverability. However, as in the largest presentday birds, Pteranodon’s large size precluded sustained beating of the wings, so it most likely soared more than it flapped. The eyes were relatively large, and the animal may have relied heavily upon sight as it searched for food above the sea.

Fossils of Pteranodon and related forms are found in Europe, South America, and Asia in rocks formed from substances found in marine environments, which supports the inference of a pelican-like lifestyle. It is probable that Pteranodon took off from the water by facing into sea breezes that provided enough force to lift the reptile into the air when the wings were spread.

Scaphites is an extinct genus of cephalopods (animals related to the modern octopus, squid, and nautilus) found as fossils in marine deposits. Because Scaphites is restricted to certain divisions of Cretaceous time, it is a useful index, or guide, fossil. Its shell form and manner of growth are quite unusual. At first, the shell in Scaphites is tightly coiled. Later, it grows in a straight fashion but then coils again at its terminus, and the mature shell takes the form of a double loop linked by a straight segment.

Turritellids include any of several species of gastropods (snails) abundantly belonging to the genus Turritella and represented in fossil and living form from the Cretaceous Period up to the present. Many forms or species of turritellids are known. All are characterized by a high, pointed shell that narrows greatly at the apex. The shell is frequently ornamented by lines, ridges, or grooves.

As plant and animal life continued to evolve during the Cretaceous, so to did the landscape. Although the Cretaceous Period was known for its tectonic activity, the interval was also characterized by the deposition of chalks, marine limestones, carbon-rich shales, coal, and petroleum. In addition, the Sierra Nevada mountain range emerged during the Cretaceous, and the eruptions of the Deccan Traps in India branded the end of the period as a time of intense volcanism.

In the course of approximately 30 million years during the middle of the Cretaceous Period, more than 50 percent of the world’s known petroleum reserves were formed. Almost three-fourths of this mid-Cretaceous petroleum accumulated in a relatively small region around what is now the Persian Gulf. Much of the remainder accumulated in another limited region, of the Americas between the Gulf of Mexico and Venezuela. Evidently the low-latitude Tethys seaway collected along its margins large amounts of organic matter, which today are found as petroleum in the Gulf Coast of the United States and Mexico, the Maracaibo Basin in Venezuela, the Sirte (or Surt) Basin in Libya, and the Persian Gulf region. Other mineral deposits of commercial value occur in the circum-Pacific mountain systems and chain of island arcs. Such metals as gold, silver, copper, lead, zinc, molybdenum, tungsten, tin, iron, and manganese were concentrated into ore deposits of various dimensions during episodes of igneous activity in the late Mesozoic.

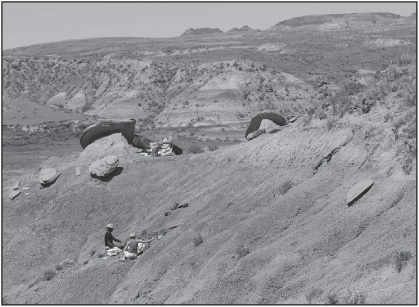

The occurrence and distribution of Cretaceous rocks resulted from the interplay of many forces. The most important of these were the position of the continental landmasses, level of the sea relative to these landmasses, local tectonic and orogenic (mountain-building) activity, climatic conditions, availability of source material (for example, sands, clays, and even the remains of marine animals and plants), volcanic activity, and the history of rocks and sediments after intrusion or deposition. The plate tectonics of some regions were especially active during the Cretaceous. Japan, for example, has a sedimentary record that varies in time from island to island, north to south. The Pacific margin of Canada shows evidence of an Early Cretaceous inundation, but by the Late Cretaceous much of the region had been uplifted 800 to 2,000 metres (2,600 to 6,600 feet). Chalks and limestones, on the other hand, were deposited underwater in the western interior of North America when sea levels were at their highest. Many Cretaceous sedimentary rocks have been eroded since their deposition, while others are merely covered by younger sediments or are presently underwater or both.

A comparison of the rock record for the North American western interior with that for eastern England reveals chalk deposition in eastern England from Cenomanian to Maastrichtian time, whereas chalks and marine limestone are limited to late Cenomanian through early Santonian time in North America. Yet the two areas have nearly identical histories of inundation. It has been noted that the only land areas of western Europe during the Late Cretaceous were a few stable regions representing low-lying islands within a chalk sea. Sedimentary evidence indicates an arid climate that would have minimized erosion of these islands and limited the deposition of sands and clays in the basin. In contrast, the North American interior sea received abundant clastic sediments, eroded from the new mountains along its western margin.

In North America the Nevadan orogeny took place in the Sierra Nevada and the Klamath Mountains from Late Jurassic to Early Cretaceous times; the Sevier orogeny produced mountains in Utah and Idaho in the mid-Cretaceous; and the Laramide orogeny, with its thrust faulting, gave rise to the Rocky Mountains and Mexico’s Sierra Madre Oriental during the Late Cretaceous to Early Paleogene. In the South American Andean system, mountain building reached its climax in the mid-Late Cretaceous. In Japan the Sakawa orogeny proceeded through a number of phases during the Cretaceous.

In addition to the areas that have been mentioned above, Cretaceous rocks crop out in the Arctic, Greenland, central California, the Gulf and Atlantic coastal plains of the United States, central and southern Mexico, and the Caribbean islands of Jamaica, Puerto Rico, Cuba, and Hispaniola. In Central and South America, Cretaceous rocks are found in Panama, Venezuela, Colombia, Ecuador, Peru, eastern and northeastern Brazil, and central and southern Argentina. Most European countries have Cretaceous rocks exposed at the surface. North Africa, West Africa, coastal South Africa, Madagascar, Arabia, Iran, and the Caucasus all have extensive Cretaceous outcrops, as do eastern Siberia, Tibet, India, China, Japan, Southeast Asia, New Guinea, Borneo, Australia, New Zealand, and Antarctica.

The rocks and sediments of the Cretaceous System show considerable variation in their lithologic character and the thickness of their sequences. Mountain-building episodes accompanied by volcanism and plutonic intrusion took place in the circum-Pacific region and in the area of the present-day Alps. The erosion of these mountains produced clastic sediments—such as conglomerates, sandstones, and shales—on their flanks. The igneous rocks of Cretaceous age in the circum-Pacific area are widely exposed.

The Cretaceous Period was a time of great inundation by shallow seas that created swamp conditions favourable for the accumulation of fossil fuels at the margin of land areas. Coal-bearing strata are found in some parts of Cretaceous sequences in Siberia, Australia, New Zealand, Mexico, and the western United States.

Farther offshore, chalks are widely distributed in the Late Cretaceous. Another rock type, called the Urgonian limestone, is similarly widespread in the Upper Barremian–Lower Aptian. This massive limestone facies, whose name is commonly associated with rudists, is found in Mexico, Spain, southern France, Switzerland, Bulgaria, Central Asia, and North Africa.

The mid-Cretaceous was a time of extensive deposition of carbon-rich shale. These so-called black shales result when there is severe deficiency of oxygen in the bottom waters of the oceans. Some authorities believe that this oxygen deficiency, which also resulted in the extinction of many forms of marine life, was caused by extensive undersea volcanism about 93 million years ago. Others believe that oxygen declined as a consequence of poor ocean circulation, which is thought to have resulted from the generally warmer climate that prevailed during the Cretaceous, the temperature difference between the poles and the Equator being much smaller than at present, and the restriction of the North Atlantic, South Atlantic, and Tethys. Cretaceous black shales are extensively distributed on various continental areas, such as the western interior of North America, the Alps, the Apennines of Italy, western South America, western Australia, western Africa, and southern Greenland. They also occur in the Atlantic Ocean, as revealed by the Deep Sea Drilling Program (a scientific program initiated in 1968 to study the ocean bottom), and in the Pacific, as noted on several seamounts.