It was a time of huge “thunder lizards” roaming steamy fern jungles; of “mammal-reptiles” walking the land of Laurasia; of continental movements, mountain building, and massive volcanoes; and a time of the most horrific, earth-shattering extinctions that ever occurred on this planet. It was the middle times of what is called the Phanerozoic Eon, a geologic interval lasting almost a half billion years. It was the time of the dinosaurs…and much, much more. We call this time the Mesozoic Era.

Dinosaurs. The word itself immediately calls to mind large, predatory reptiles stalking the Earth. As young and old alike experience such visual, visceral responses to the word, it is difficult to believe that a mere 200 years ago, no one had any idea that these creatures had ever existed. This book takes readers back to that point of discovery and classification, when English anatomist Sir Richard Owen first attempted to classify strange bones found in his country. And discoveries continue. Readers will learn about new and contradictory ideas of what the dinosaurs were—and were not. Were they cold-blooded? Did they all vanish in an extinction? The answers might surprise you.

Dinosaurs were the dominant life form of the Mesozoic Era. Each period within that era had a different variety of these amazing creatures, but all can generally be assigned to one of two major groups: Saurischia (“lizard hips”) or Ornithischia (“bird hips”). Those in the Saurischia group belong to either the Sauropodomorpha subgroup, which consist of herbivores, or the Theropoda subgroup, the carnivores. Examples of the first subgroup would include the Brontosaurs, an out-of-date term, but one which many people can identify as the massive long-necked leaf-eater of cartoons. These animals could reach 30 metres (100 feet) in length and weigh in excess of 70 metric tons. Probably the most recognizable theropod would be the mighty Tyrannosaurus rex, 15 metres (50 feet) and 5 metric tons of mean, hungry lizard machine. Ornithischia include such dinosaurs as the Stegosaurus and Triceratops, both herbivores and, again, immediately recognizable.

Readers will also learn about the flora and geology of this era. As one might imagine, many events can take place over the course of 185 million years; having the luxury of peering back and reading a condensed yet thorough distillation of this massive period of time in easily decipherable segments provides readers the opportunity to review the whole era in sequences and overlays that make sense to the modern mind.

Mesozoic is a Greek term meaning “Middle Life,” and is so-called due to the fact that it comes after the Paleozoic Era (“Old” or “Ancient Life”) and before the Cenozoic Era (“New” or “Recent Life”), all three comprising the Phanerozoic Eon. It was just before the Mesozoic Era that the Earth’s greatest mass extinction ever—the Permian extinction—occurred. At that time, approximately 251 million years ago, over 90 percent of marine invertebrates and 70 percent of land vertebrates inexplicably disappeared. This life change resulted in a great diversification of vertebrate life, which, along with tremendous geologic changes, caused the start of ecosystems on Earth that resembled those of modern times.

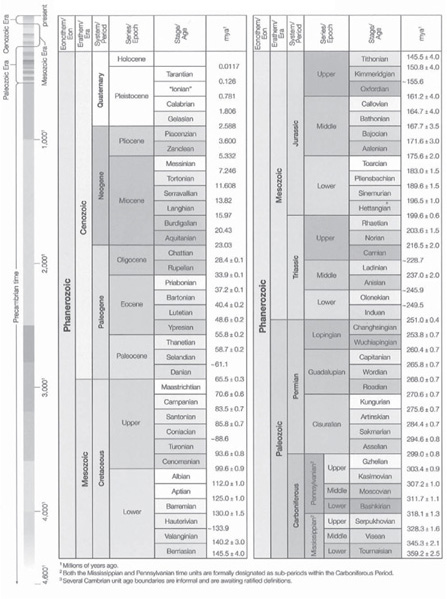

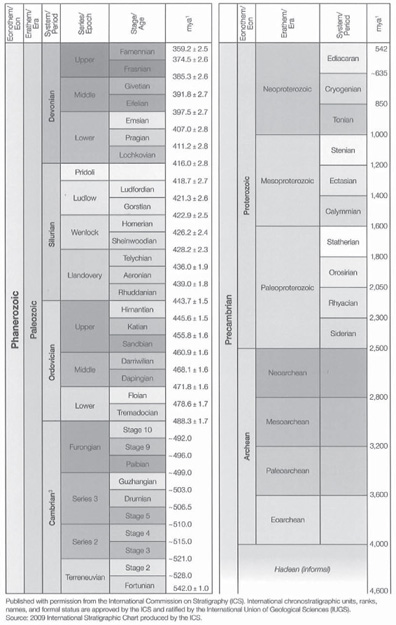

So, what was it like at the start of the Mesozoic Era? First, we have to realize that in speaking of these times and circumstances, a few hundred thousand years seems to pass in the blink of an eye. Knowing that many important changes can actually occur such a large timeframe, scientists subdivide larger time periods into smaller sequences so as to keep a perspective of the larger time interval while focusing on more specific time developments. In the case of the Mesozoic Era, it is further split into three periods: the Triassic (251 million–200 million years ago), the Jurassic (200 million–145 million years ago), and the Cretaceous (145 million–65.5 million years ago). The book will further refine these periods (e.g., upper, middle, lower, and so on), but we will focus on the bigger picture for now.

The Triassic Period begins with the Earth appearing far different than it does today. If one could look at the ancient world from outer space, the surface of our planet would appear to be all blue liquid except for one huge land mass. We call this mass Pangea, and as we fast-forward toward the Jurassic period, we see that the land starts to break up from the middle along the equator to form two separate continents: Laurasia in the north and Gondwana in the south. This continental rift was caused by numerous geologic forces, most importantly the shifting of subsurface rock plates. The expanding water mass that would eventually separated these continents from one another was the Tethys Sea, a massive salt-water ocean that flowed from east to west.

Plant life on Pangea was dominated by seed ferns at lower levels of the forest, gymnosperms (with outer seeds) at middle levels, and conifers higher up. There forests were different than present-day forest ecosystems. The warm, relatively dry climate did not allow for much growth. This would change during the latter part of the Triassic period.

And what was swimming—or crawling—around in the ocean during the Triassic? As previously mentioned, most marine invertebrates became extinct with the Permian extinction: Ammonoids, early mollusk predecessors of octopus and squid, had almost died out in the early Triassic, but were revitalized much later on. Many species of fishes faded away after the huge extinction, replaced by others that thrived and filled the sea, among them shellfish-eating hybodont sharks and various varieties of ray-finned fishes. Marine reptiles were represented by nothosaurs (from which would come the plesiosaurs in the Jurassic) as well as ichthyosaurs, animals that resembled streamlined dolphins and may have preyed upon early squid-like creatures called belemnites.

GEOLOGIC TIME SCALE

Encyclopædia Britannica, Inc. Source: International Commission on Stratigraphy (ICS)

Pangea was home to the earliest ancestors of today’s lizards, turtles, and crocodiles. Although very small, mammal-like creatures existed during this time, they would never dominate any area. Such mammal-like creatures would eventually fade away as more efficient predators consistently won the best food and shelter. Thecodonts, ancestors of dinosaurs and crocodiles, were represented by Lagosuchus, small, swift bipedal lizards; the small gliding Icarosaurus; and the somewhat larger Sharovipteryx, the first true pterosaur (flying lizard). All of these animals would become extinct by the latter stages of the Triassic, as their niches were assumed by the larger pterosaurs and earliest dinosaurs.

As for what types of dinosaurs were around in the Triassic period, generally, they were smaller and lighter than what we might normally assume a dinosaur should be. Coelophysis and Herrerasaurus are two examples of such dinosaurs, approximately 2 metres (6.5 feet), 20 kg (45 pounds) and 3 metres (10 feet), 181 kg (400 pounds), respectively. The largest dinosaur during the Triassic period was probably Plateosaurus; at about 8 metres (26 feet) long; it was actually larger than many dinosaurs that would follow, and it was the first real large herbivorous dinosaur.

It was during the Triassic period that Cynognathus, a wolf-sized predator that was a forerunner to present-day mammals, appeared. Leptolepis, an ancient herring type of fish, generally assumed to be the progenitor of almost all modern-day fishes, also made its entrance during this period.

The Jurassic Period was as geologically active as the Triassic was tame. It was during this period that increased plate tectonic movement caused Pangea to split apart, creating massive mountains and producing extreme volcanic activity. As continents collided, the upthrusts were responsible for creating what would become the Rocky mountain range, the Andes mountain range, and a large assortment of smaller mountain groupings. Geologists can ascertain much of what occurred by comparing formations of rock from different places and seeing rocks and fossils between them. It is this type of research methodology that helps us understand that the modern-day continent of Africa was once joined with modern-day South America and that huge igneous and metamorphic rock formations found from Alaska to Baja, California were the result of one common event.

From the middle to the late Jurassic Period both sea and air temperatures increased, most likely the result of increased volcanic activity and a moving seafloor, which in turn released large amounts of carbon dioxide (CO2). Being a “greenhouse gas,” increased CO2 concentrations would have contributed to higher overall temperatures around the globe and consequently to more tropical, sluggish waters and decreased wind activity.

And what of marine life at this time? In these warm oceans there had occurred a major extinction at the beginning of the Jurassic, and a number of smaller extinction events throughout the first half of the period. Great diversification of marine species, from giant to microscopic, resulted. In addition, different types of plankton emerged that would form the deep-sea sediments we find today, and the largest bony fish that ever existed, Leedsichthys, swam in the same waters as some of the largest pliosaurs (carnivorous reptiles) ever recorded. Also, the first true lobsters and crabs appeared, and the mollusks and shrimp were varied and plentiful. Jurassic seas could have provided a number of huge seafood dinners—and they did. The impact of extensive predatory activity led to the “Mesozoic Marine Revolution,” a continual battle between prey and predators that led to increased diversification of marine animals and their behaviours.

On land the story was much the. The most abundant terrestrial life forms were insects, including dragonflies, beetles, flies, ants and bees, the last providing an intriguing clue as to when the first flowering plants appeared on Earth. Dinosaurs multiplied and flourished; it was during the early Jurassic that Sauropods first appeared, reaching their peak size, number, and diversity during the later Jurassic. If we were able to observe the dinosaur inhabitants of the later Jurassic period, what we would see? Allosaurus, a relatively large carnivore at 11 metres (35 feet) and nearly 2 metric tons might be stealthily walking upright, sneaking toward a spike-tailed, armour-plated Stegosaurus munching on ferns, as a Steneosaurus, an extinct crocodilian, swam by the shore.

There were numerous plant-eaters and meat-eaters, the most impressive and probably most recognized being the Tyrannosaurus rex. Topping out at about 6.5 metres (21 feet) tall and weighing up to 7,000 kg (about 9,000 to 15,000 pounds), these dinosaurs were voracious predators, proven by study of both bite marks shown on various prey animals and coprolite (fossilized feces) of the giant predator. The first bird, Archaeopteryx, also dates back to the late Jurassic.

The last period of the Mesozoic Era is the Cretaceous Period, spanning a total of 80 million years. It was by the end of this period that most of Pangea had evolved into present-daycontinents. (The exceptions were India, which was surrounded by ocean, and Australia, which was still connected to Antarctica.) The Cretaceous climate was warmer than today, with the polar regions covered with forest rather than ice. Both ocean circulation and wind activity were depressed during the Cretaceous due to this warm climate.

This was the period when different groups of plants and animals developed modern characteristics that were shaped before the mass extinction that marks the end of this period. Almost all flowering plants and placental mammals appeared during the Cretaceous, and many other groups (plankton, clams, snails, snakes, lizards, fishes) had developed into modern varieties by this time. Pterosaurs (flying reptiles) were abundant in the skies, and dinosaurs, including those with feathers, horns, or armour, evolved throughout the period. Albertosaurs, slightly smaller versions of, and probable ancestors to, T. rex, were common, as were Triceratops, a type of large plant-eater with a thick bony collar and three horns for defence. Triceratops was most likely one of the last dinosaurs to have evolved, with fossils dating only to the last 5 million years of this period.

Numerous plant-eaters (Pentaceratops, Psittacosaurus, Pachyrhinosaurus, Maiasaura, etc.) existed during the Cretaceous, as did almost as many meat-eaters (Dromaeosaurus, Caudipteryx, Deinonychus, Velociraptor), including the largest carnivorous dinosaur discovered to date: Spinosaurus, maxing out at 59 feet and 22 tons. Its skull alone was nearly 1.75 metres (6 feet) long. Other significant life forms included mammals related to modern rats and ungulates (e.g., deer).

The term “Cretaceous” comes from the French word “chalk,” and was used to describe this period due to its massive chalk deposits created from certain plankton types. Chalk was far from the most significant geologic feature, however. It was during the Cretaceous that the majority of the world’s petroleum and coal deposits were formed, and massive ore deposits containing gold, silver, copper, and many more metals were formed during igneous activity also.

The Cretaceous Period—and the Mesozoic Era—came to a sudden end roughly 65.5 million years ago. Many scientists contend that this transition is somehow related to the strike of a 9.5 km (6-mile) diameter asteroid in what is today called the Yucatan Peninsula of Mexico Although it has been discovered that numerous organisms had gone extinct some millions of years prior to the impact, the asteroid may have been responsible for the disappearance of a massive number of species, either directly or through attrition because of colder temperatures caused by huge ash plumes. As the Cretaceous period ended, the Cenozoic or modern era began, a time that has taken the remnant flora and fauna of the Cretaceous—living groups that were already present at the Cretaceous end—and further transformed the Earth and its organisms into what we see about us today.