IN THE DAYS THAT DAVE THEURER WAS BEGINNING TO DEVELOP Missile Command at Atari, there was an all-too-common scenario called the Atari Trap, which was the exact manifestation of the work that was described earlier: full devotion to making the best game you possibly could and the long, endless nights required to make that a reality. In a company focused on getting out as many hits as possible, this was extremely common as developers spent sleepless nights finding the best ways to make their game enjoyable in the shortest amount of time. Release good games, and do it often.

Theurer was an unusual case. He poured his heart and soul into the project, but from the very beginning, he stressed the value of a work-life balance. He was fine spending long nights on the project in order to get something done, but he never wanted this to become the norm and worked hard to make that a reality. In the beginning of the project, this was quite easy, despite his overwhelming excitement for what the game could become. He was able to go home on time and create a healthy sense of balance between work and the rest of his life. But as he progressed in development and the game’s grip on him grew tighter and tighter, he wasn’t able to put up as much of a fight. He tried to avoid it, but like many others before him, he fell prey to the trap and allowed the project to consume and dominate his time.

Before Missile Command, most of these projects at Atari were one-man shows. There was only a single programmer on most projects who was in charge of both design and the actual code implementations. This programmer worked with engineers and other team members when necessary, but it still wasn’t common to have a big team—you were expected to be able to do most of it on your own. But with Missile Command being such a big project, Theurer was given a junior programmer to help with some of the coding. Enter Rich Adam.

Adam was the perfect equalizer to Theurer. For every time that Theurer brought up the greater implications of the game to players, Adam focused on the fun of it all. For every time Theurer said it was about sending a greater message, Adam said enjoyment was the only metric. For some this may seem like the most tumultuous of relationships, but for them it was a balance of yin and yang. They were each other’s counterbalances, and they liked it that way.

This changed the dynamic at play between the two of them, especially when it came to their working relationship. They hadn’t worked together before, and it was a learning experience from the get-go. Most programmers at Atari were used to doing things on their own. They hadn’t ever had to answer to anyone but themselves, and maybe their bosses, but most of the times bosses were pretty hands-off once someone had started on a project. As long as you hit your deadline, you were good to go—and even then, they called the shots, so it didn’t really matter.

This was different with Missile Command; not just with Adam having to report to Theurer as his senior manager, but in Theurer doing right by Adam. With all the eyes on the project, he knew it wasn’t just about him, but that they needed to work with each other to succeed.

One of the main reasons that Adam was brought in was to ensure they met a strict manufacturing deadline. Atari had become such a commercial success that it felt a need to create its own manufacturing facility down the road from the Moffett Park offices. With only eight releases in 1979, the manufacturing facility was effectively on standby, waiting for programmers to get the green light that their projects were ready to go. Because of this, there was a very real need for Theurer and Adam to hit the relatively tight deadline imposed on them by Steve Calfee.

These workers were just waiting around for games to come in. There was only so much work they could do ahead of the game coming in or finalizing design work. “[The workers] needed games to manufacture,” recalls Adam. “They needed the designs for the cabinets we were going to build and ship.” You could only predesign cabinets to a certain extent, as the game teams often found themselves coming up with new and unique cabinet designs to stand out in the arcades, which were quickly becoming crowded with dozens of other fun games. They needed to stand out. But because of this, the workers were stuck, and their team began feeling the heat on ensuring they didn’t encounter any delays. With this being their first project together, Theurer and Adam knew they didn’t have the luxury of being able to mess this up.

Not only did they need the cabinets built and ready to go, but they had to manufacture the circuit boards, often referred to as ROMs (for “read-only memory”), that the game would live on—and this was the big one. The sheer scale of the project exposed Adam to a new level of pressure he had never experienced before. If you made a mistake and didn’t catch it before sending it off to manufacturing, that mistake was present on hundreds of thousands of ROMs. You had two options: leave it, or fix it—and fixing it wasn’t cheap. In fact, the additional manufacturing cost to fix something was deemed an unallowable expense, one they couldn’t afford to run into. You had to get it right the first time—and fast.

Theurer and Adam grouped up and set off to work on the game, eliminating core elements of the original pitch in order to land on a design that focused on fun above all else. They cut out suggestions from Steve Calfee and Gene Lipkin, focusing on finding alternatives to the problems they were being asked to solve with this design. At the time, it didn’t seem crazy—just work, like any other project. There’s a strong inclination in successful creators to look back on their creation as if it was a perfectly executed plan of success. In reality, it doesn’t always play out that way—it can just feel like work that ends up being really good. That’s exactly what Missile Command was to Theurer and Adam. That’s not to say they weren’t excited; they clearly were, but there had been dozens of titles before that Atari programmers thought would be fun that had never seen the light of day.

For Adam, it was no different from every other game he’d worked on. “Everybody thinks of that as ‘the golden age,’ but to us it wasn’t,” he remembers. “We were just working and making stuff.” To Adam, it didn’t feel like a revolutionary time—it was just work. It was something special they were proud to be making, but they didn’t spend their days thinking, “Man, these are special times that we’re going to look back on fondly as the birthplace of gaming narrative.” It was nothing like that—at least not for Adam.

Theurer was a bit different. He knew it was special. It wasn’t just a game to him. It wasn’t like other projects he had worked on previously. It was a unique opportunity to make a game that was extremely engaging but also carried an important message. This message was one of hope, hope that one could somehow keep this nuclear nightmare from becoming reality. And for Theurer, there was hope, deep down, that he could somehow influence players and change their perception, showing them what a massive error it was to assume war was the only way. His vision was much deeper than creating an entertaining game; he wanted to craft a meaningful legacy with it, something that no game had truly accomplished to that point. People had really liked Pong, and still do to this day, but that’s a different kind of legacy than what Theurer was hoping to accomplish. He didn’t want Missile Command to be around in forty years solely for its gameplay merits. He wanted its effect to be more powerful.

Dave Theurer standing in front of the newspaper photo from his hit-and-run assistance.

(Credit: Game Developers Conference)

Dave Theurer accepts his Pioneer Award at the 2012 Game Developers Conference in San Francisco, CA.

(Credit: Game Developers Conference)

Atari founder Nolan Bushnell in Madrid, Spain.

(Credit: Javier Candeira)

Nolan Bushnell signs an original Atari 2600 at Campus Party Mexico in 2013.

(Credit: Campus Party Mexico)

Pac-Man corner at Funspot Family Fun Center in New Hampshire.

(Credit: @AzyxA on Instagram)

The reflective Missile Command marquee at Funspot Family Fun Center, where Tony Temple achieved his high score.

(Credit: @AzyxA on Instagram)

The front of the original Atari VCS wood grain home console. As it was the first time people were being asked to add video games to their home décor, Atari wanted it to blend with common home entertainment setups of the period.

(Credit: Moparx.com)

An original Pong home console at the Henry Ford Museum in Dearborn, Michigan.

(Credit: Mark Cameron)

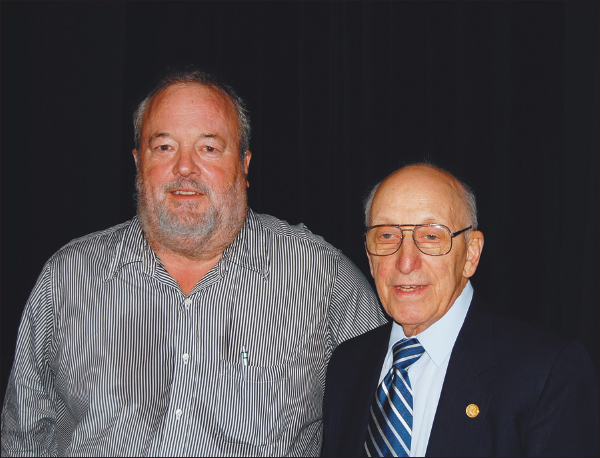

Al Alcorn with Ralph Baer at the 2008 Game Developers Conference in San Francisco, CA.

(Credit: Alex Handy)

Computer Space and Pong, side by side, at the Museum of the Moving Image in Queens, NY.

(Credit: Mel Boysen)

Missile Command Tournament Settings World Champion, Tony Temple, alongside his personal Missile Command cabinet at his home in the UK.

(Credit: Tony Temple)

The artwork on the arcade cabinet marquee of Tempest, inspired by Dave Theurer’s nightmares as a child.

(Credit: Mene Tekel)

A custom neon Atari sign adorns the walls of Dogs ’n’ Dough, which features an amazing selection of retro arcade classics, in the heart of Manchester, England.

(Credit: Mark Webster)

A Missile Command display at the Game Masters exhibit in Halmstad, Sweden, that showcased the most impactful games in video game history.

(Credit: Retro-Video-Gaming.com)

The well-used control panel of the Missile Command cabinet on display at the Game Masters exhibit in Halmstad, Sweden.

(Credit: Retro-Video-Gaming.com)

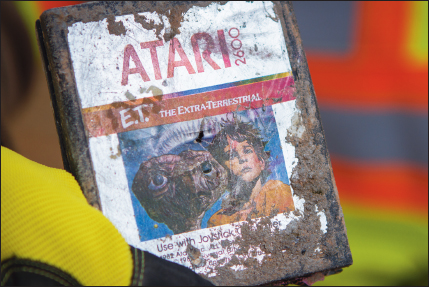

An excavated copy of Atari’s E.T. The Extra-Terrestrial that was the subject of a massive urban legend, finally confirmed in the 2014 excavation of the suspected desert dump site.

(Credit: Ed Martinez)

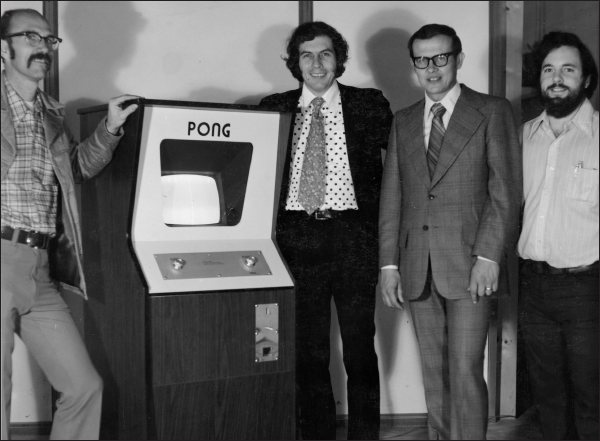

Ted Dabney, Nolan Bushnell, and Al Alcorn with the original Pong cabinet.

(Credit: Nolan Bushnell)

Author Alex Rubens posing with a Missile Command machine at his wedding in June 2018.

(Credit: Ivy Reynolds)

As they progressed further into development, Theurer started to fall deeper and deeper into this goal, subtly pushing the development down that path, all unbeknownst to Adam. While Adam thought they were beginning to make good progress on the game they’d been working on for a few weeks at this point, Theurer was finding himself consumed by the fear-stricken worry he was attempting to induce in the player.

It had only been weeks, but the very thought of what they were trying to get across had already taken its hold on Theurer. Adam? Not so much. Sure, people are different and react to things in different ways. But how could one member of the team be drawn to such a powerful narrative while the other was left completely unaffected?

Oddly enough, this was the end goal with Missile Command all along. Theurer knew that they would never get their message across to everyone who played the game, and that 99 percent of players would never think more deeply about what they were playing, but it was a mission for him nonetheless.

If you ask Adam why Theurer was so driven to get this message across, it has to do with his heroic qualities that, more than thirty years after they worked together, still stand out to Adam as unique. Adam saw him as an “incredibly ethical and honest person” who just gave off this superhero “good guy” vibe that was undeniable. In the same way that Superman feels compelled to save those in distress, Theurer carried with him an air that he could always be of help—that there was always something for him to be doing to make his world a better place. And that was true for all facets of his life, not just his work on Missile Command. It wasn’t just evident to Adam that these qualities existed within Theurer; it was clear in the way Theurer went about his life.

In 1983, three years after the release of Missile Command, Theurer was driving his Porsche 928 to watch a fireworks celebration at Moffett Field, a local joint civil-military airport located between Mountain View and Sunnyvale in Santa Clara County, California, when the unthinkable happened. Right in front of his eyes, he watched as a car plowed into a teenage pedestrian and took off. He stopped to help the injured pedestrian and, once he had ensured that other passersby could assist, got back into his car to chase down the hit-and-run driver. He turned onto I-280, putting the 234 horsepower, 4.7 liter V8 to use, racing down the freeway after the fleeing driver. He caught up to him, forcing him to pull over. He was then somehow able to convince the driver to turn himself in and assisted in returning him to the scene, where he was arrested on charges of felony hit-and-run, drunk driving, giving false information to a police officer, and driving without a license. The teenager who had been hit by the driver ended up being paralyzed from the waist down from the collision, and the police said that had Theurer not chased down the driver and convinced him to return to the scene, they most likely would never have caught him.

That’s the type of person Dave Theurer is. He risked his own life to chase down a hit-and-run suspect who had clearly shown no regard for human life and brought him to justice simply because it was the right thing to do. To Theurer, this wasn’t a heroic act; it’s just what you do—it’s your duty, your responsibility as a human being. That is obviously an extreme example of Theurer’s heroic nature, but for those who knew him, it was just one act of many that exemplified his character.

Because of his selfless, proactive nature, Theurer felt compelled to do what he thought was right and do his part in making the world a better place. As work on Missile Command progressed and their deadline drew nearer with each passing day, his commitment to finishing it began to consume his every thought.

Would they finish the game in time? Would it be fun? Would it sell? Would anyone understand the message he was trying to impart? Was the message important enough for others? Would the player actually learn anything from it? Was this the right medium with which to impart the message? Would the game create a lasting legacy with the player that went beyond the simple insertion of a quarter into a coin slot?

These were the questions that drove Dave Theurer, and as they circulated in his head, they began to transform from the standard questions that one asks oneself when working on a creative endeavor to an obsession that he couldn’t erase from his mind, pushing him to a place he never expected to be at while working on an arcade game. It became less about the business implications of whether they could meet the deadline and people would play the game, and more about the art that Theurer was looking to create.

As this obsession increased and began to consume more and more of his thoughts, Theurer began to worry that he was going down a bad path. But he knew it would be over soon, and he didn’t want to burden anyone; he was, after all, a problem solver, not a problem haver. It was in his nature to keep it to himself, and that’s exactly what he did. He didn’t speak much about it to Adam or anyone else, but, as Theurer recalls, the further they progressed in development, the “more stressed and obsessed with trying to finish” the game he became.

As his brain entered this state of obsession, the destructive nature of the game began to take hold on a deeper level than Theurer had ever imagined possible. It’s well documented that creators can often have very tumultuous relationships with their creations: they love what they’re working on, but hate the way the need to make it perfect consumes their very being. Some don’t know when to stop working or when “good enough” is really good enough. There are too many long nights at the office and broken relationships as they struggle to please everyone while simultaneously pleasing no one—not even themselves. This is an extremely common tendency in high-performing creative people. It’s also extremely destructive. Most of the time such people reach their breaking point. It becomes too much to handle and they aren’t able to balance everything they need to retain a semblance of completeness.

The breaking point is different for everyone, as is the path to that point, but the process is a result of wanting your creation to be just right—that perfect blend that accomplishes what you want it to for all people. Theurer had a message he hoped to share, but for that to work successfully, he had to ensure that the game was also perfect for people who would never absorb that message. He didn’t want to force anything and, despite his defensive approach being a prerequisite to making the game, he knew it needed to be captivating or no one would ever care enough to experience it.

As he worked to make all these pieces fit together, in an attempt to answer all the questions he couldn’t shake off, he began to spend every waking hour in his Atari office. He wanted the game to be just right, but with this obsession, he began to encounter fatigue as he watched city after city destroyed by nuclear war. These visions escaped the game world and seeped into his conscience. He began to experience exactly what he had hoped players would feel, which, while oddly satisfying, left him in a place he would never return to again.