THE FIRST CRITICAL OBJECTIVE OF THE Normandy campaign, which was to establish a secure beachhead with adequate avenues of supply in the area between Cherbourg and the mouth of the Orne, was fully accomplished by the end of June.1

From the beginning it was the conception of Field Marshal Montgomery, Bradley, and myself that eventually the great movement out of the beachhead would be by an enormous left wheel, bringing our front onto the line of the Seine, with the whole area lying between that river and the Loire and as far eastward as Paris in our firm possession. This did not imply the adoption of a rigid scheme of grand tactics. It was merely an estimate of what we believed would happen when once we could concentrate the full power of our air-ground-naval team against the enemy we expected to meet in northwest France.

An important point in our calculations was the line from which we originally intended to execute this wheel. This part of our tactical prognostications did not work out and required adjustment. The plan, formally presented by Montgomery on May 15, stated: “Once we can get control of the main enemy lateral Granville–Vire–Argentan–Falaise–Caen, and the area enclosed in it is firmly in our possession, then we will have the lodgment area we want and can begin to expand.”

This line we had hoped to have by June 23, or D plus 17.2 In his more detailed presentation of April 7, Montgomery stated that the second great phase of the operation, estimated to begin shortly after D plus 20, would require the British Army to pivot on its left at Falaise, to “swing with its right toward Argentan–Alençon.” This meant that Falaise would be in our possession before the great wheel began. The line that we actually held when the breakout began on D plus 50 was approximately that planned for D plus 5.

This was a far different story, but one which had to be accepted. Battle is not a one-sided affair. It is a case of action and reciprocal action repeated over and over again as contestants seek to gain position and other advantage by which they may inflict the greatest possible damage upon their respective opponents.

In this case the importance of the Caen area to the enemy had caused him to use great force in its defense. Its capture became a temporary impossibility or, if not that, at least an operation to be accomplished at such cost as to be almost prohibitive.

Naturally this development caused difficulties. Had we been successful in our first rush in gaining the open ground south of Caen, the advance of the Americans to the Avranches region might have become, instead of the dogged battle that it was, a mere push against German withdrawals. That is, greater initial success on our left should have made easier attainment, on our right, of a satisfactory jump-off line from which to initiate the great wheel.

As the days wore on after the initial landing the particular dissatisfaction of the press was directed toward the lack of progress on our left. Naturally I and all of my senior commanders and staff were greatly concerned about this static situation near Caen. Every possible means of breaking the deadlock was considered and I repeatedly urged Montgomery to speed up and intensify his efforts to the limit. He threw in attack after attack, gallantly conducted and heavily supported by artillery and air, but German resistance was not crushed.

Further, one must realize that when the enemy, by intensive action or concentration of forces, succeeds in balking a portion of our own forces, he usually does so at the expense of his ability to support adequately other portions of the field. In this instance, even though the breakout would now have to be initiated from farther back than originally planned, it was obvious that if the mass of enemy forces could be held in front of Caen there would be fewer on the western flank to oppose the American columns. This was indeed fortunate in view of the difficult type of country through which the Americans would have to advance. These developments were constantly discussed with Bradley and Montgomery; the latter was still in charge of tactical co-ordination of ground forces in the crowded beachhead.

By June 30, Montgomery had obviously become convinced, as Bradley and I already had, that the breakout would have to be launched from the more restricted line. His directive of that date clearly stated that the British Second Army on the left would continue its attacks to attract the greatest possible portion of enemy strength, while the American forces, which had captured Cherbourg four days before, would begin attacking southward with a view to final breakout on the right flank.3 From that moment onward this specific battle plan did not vary, and although the nature of the terrain and enemy resistance combined with weather to delay the final all-out attack until July 25, the interim was used in battling for position and in building up necessary reserves.

This, of course, placed upon the American forces a more onerous and irksome task than had at first been anticipated. However, Bradley thoroughly understood the situation of the moment and as early as June 20 had expressed to me the conviction that the breakout on the right would have to be initiated from positions near St. Lô, rather than from the more southerly line originally planned. He sensed the task with his usual imperturbability and set about it in workmanlike fashion. He rationed the expenditure of ammunition all along the front, rotated troops in the front lines, and constantly kept his units and logistic elements in such condition as to strike suddenly and with his full power when the opportunity should present itself.

Complicating the problem of the breakout on the American front was the prevalence of formidable hedgerows in the bocage country. In this region the fields have for centuries past been divided into very small areas, sometimes scarcely more than building-lot size, each surrounded by a dense and heavy hedge which ordinarily grows out of a bank of earth three or four feet in height. Sometimes these hedges and supporting banks are double, forming a ready-made trench between them, and of course affording almost the ultimate in battlefield protection and natural camouflage. In almost every row were hidden machine gunners or small combat teams who were in perfect position to decimate our infantry as they doggedly crawled and crept to the attack along every avenue of approach.

Our tanks could help but little. Each, attempting to penetrate a hedgerow, was forced to climb almost vertically, thus exposing the unprotected belly of the tank and rendering it easy prey to any type of armor-piercing bullet. Equally exasperating was the fact that, with the tank snout thrust skyward, it was impossible to bring guns to bear upon the enemy; crews were helpless to defend themselves or to destroy the German.

In this dilemma an American sergeant named Culin came forth with a simple invention that restored the effectiveness of the tank and gave a tremendous boost to morale throughout the Army. It consisted merely in fastening to the front of the tank two sturdy blades of steel which, acting somewhat as scythes, cut through the bank of earth and hedges. This not only allowed the tank to penetrate the obstacle on an even keel and with its guns firing, but actually allowed it to carry forward, for some distance, a natural camouflage of amputated hedge.4

As soon as Sergeant Culin had demonstrated his invention to his captain it was speedily brought to the attention of General Walter M. Robertson of the 2d Division. He, in turn, demonstrated the appliance to Bradley, who set about the task of equipping the greatest possible number of tanks in this fashion so as to be ready for the coming battle. A feature of the incident from which our soldiers derived a gleeful satisfaction was that the steel for the cutting blades was obtained from the obstacles which the German had installed so profusely over the beaches of Normandy to prevent our landing on that coast.

However, we were still without this contrivance when the First Army began its tedious southward advance to achieve a reasonable jump-off line for the big attack. It was difficult to obtain any real picture of the battle area. One day a few of us visited a forward observation tower located on a hill, which took us to a height of about a hundred feet above the surrounding hedgerows. Our vision was so limited that I called upon the air forces to take me in a fighter plane along the battle front in an effort to gain a clear impression of what we were up against. Unfortunately, even from the vantage point of an altitude of several thousand feet there was not much to see that could be classed as helpful. As would be expected under such conditions, the artillery, except for long-range harassing fire, was of little usefulness. It was dogged “doughboy” fighting at its worst. Every division that participated in it came out of that action hardened, battle-wise, and self-confident.

Tactics, logistics, and morale—to these three the higher commanders and staffs devoted every minute of their time. Tactics to gain the best possible line from which to launch the great attack against the encircling forces. Logistics to meet our daily needs and to build up the mountains of supplies and to bring in the reserve troops we would need in order to make that attack decisive. And always we were concerned in morale because troops were called upon constantly to engage in hard fighting but denied the satisfaction of the long advances that invariably fill an army with élan. By July 2, 1944, we had landed in Normandy about 1,000,000 men, including 13 American, 11 British, and 1 Canadian divisions. In the same period we put ashore 566,648 tons of supplies and 171,532 vehicles. It was all hard and exhausting work but its accomplishment paid off in big dividends when finally we were ready to go full out against the enemy. During these first three weeks we took 41,000 prisoners. Our casualties totaled 60,771, of whom 8975 were killed.5

During the battling in the beachhead a particular development was our continued progress in the employment of air forces in direct support of the land battle. Perfection in ground-air co-ordination is difficult if not impossible to achieve.

When a pilot in a fighter bomber picks up a target on the ground below it is easily possible for him to mistake its identity. He may be ten to fifteen thousand feet in the air and unless visibility is perfect he may have difficulty in identifying the exact spot on the ground over which he is flying. In his anxiety to help his infantry comrades he may suddenly decide that the gun or truck or unit he sees on the ground belongs to the enemy, and the instant he does so he starts diving on it at terrific speed. Once having made his decision, his entire concentration is given to his target; his purpose is to achieve the greatest possible amount of destruction in the fleeting moment available to him. Only incessant training and indoctrination, together with every kind of appropriate mechanical aid, can minimize the danger of mistaken identification and attack on our own forces.

One method we used was to put an air liaison detachment in a tank belonging to the attacking unit. Each such detachment was given a radio capable of communicating with planes in the air, and through this means we not only helped to avoid accidents but were able to direct the airplane onto specific and valuable targets. The ground and air, between them, developed detailed techniques and mechanisms for improvement, with a noticeable degree of success.6

Accidents in the other direction were just as frequent. More than one friendly pilot attempting to co-operate with the ground troops has been greeted with a storm of small-arms fire and many returned to their bases bitterly complaining that the infantry did not seem to want friendly planes around. In the early days in Africa these accidents were almost daily occurrences; by the time we had won the Battle of the Beachhead they had practically ceased.

Within the high command a clear appreciation of the relationship between the strategic bombing effort in the German homeland and the needs of the land forces was essential if we were to work in common purpose and achieve the greatest possible result. As this appreciation developed among air as well as ground commanders, the early reluctance of such specialists as Air Chief Marshal Harris and General Doolittle, who commanded respectively the bomber forces of Great Britain and the U. S. Eighth Air Force, to employ their formations against so-called tactical targets completely disappeared. By the time the breakout was achieved, the emergency intervention of the entire bomber force in the land battle had come to be accepted almost as a matter of course.

To this general rule there was one notable exception. The U. S. 30th Division by unfortunate accident suffered considerable casualties from our own bombing effort, an incident that was repeated later in the campaign. To the end of the war the commander of this particular division insisted that when given attack missions he wanted no heavy or medium bombers to participate.7

It became necessary to specify a date on which the whole ground organization should take on its final form—that is, with each army group reporting directly to Supreme Headquarters. We planned to bring Patton’s army into operation on August 1, and with this development the Twelfth Army Group, under Bradley’s command, would be established in France. Command of the First Army would then pass to Lieutenant General Courtney H. Hodges, who, during the early battling, served as Bradley’s deputy. However, what could not then be foreseen was the time required to effect the eventual breakout, the completion of the enemy’s defeat in close fighting on the Normandy front, and the eventual sorting out of army groups, each into its own main channel of invasion.

Until this should come about and while all forces were operating toward the common purpose of destroying the German forces on our immediate front, it was clear that one battle commander should stay in co-ordinating authority over the whole line. Our estimate of the date that these conditions would prevail was September 1 and senior commanders were notified that on that date each army group would operate in direct subordination to Supreme Headquarters.8 Fortunately my personal headquarters was located so conveniently to the headquarters of both Montgomery and Bradley that I could visit each easily.9

The July battling all along the front involved some of the fiercest and most sanguinary fighting of the war. On the American front every attack was channelized by swamps and streams and the ground was unusually advantageous to the defense. Many of Bradley’s subordinates made names for themselves during this period, clearly establishing their right to be numbered among the best of America’s tacticians. Our corps and division commanders, to say nothing of hundreds of more junior officers, generally demonstrated qualities of leadership and tactical skill that stamped them as top-flight battle leaders; the same was true in the armies of our Allies. And among our troops, whatever their nationality or flag, stubborn courage was an outstanding characteristic that boded inevitable defeat for the enemy.

Just after the middle of July the U. S. First Army attained, on its portion of the front, the line—St. Lô to the west coast—from which it could launch a powerful assault. At that moment the weather, which had been bad, grew abominably worse and for the following week all of us went through a period of agonizing tenseness. We had to draw plans to take advantage of the first favorable break in the weather, and yet we wanted to avoid the constant alerting and shifting of troops entailed by frequent initiation and postponement of orders. Earlier in the war the period would have had a most serious effect upon morale and efficiency, but the American troops had by this time become battle-wise and they passed through the ordeal of waiting like veterans.

Finally on July 25, seven weeks after D-day, the attack was launched, from the approximate line we had expected to hold on D plus 5, stretching from Caen through Caumont to St. Lô. A tremendous carpet, or area, bombing was placed along the St. Lô sector of the American front and its stunning effect upon the enemy lasted throughout the day. Unfortunately a mistake by part of the bombing forces caused a considerable number of casualties in one battalion of the 9th Division and in the 30th Division, and killed General McNair, who had gone into an observation post to watch the beginning of the attack. His death cast a gloom over all who had known this most able and devoted officer.10

Progress on the first day was slow, but that evening General Bradley observed to me that it was always slow going in the early phases of such an attack and expressed the conviction that the next day and thereafter would witness extraordinary advances by our forces. The event proved him to be completely correct. In the following week he slashed his way downward to the base of the peninsula, passing through the bottleneck at Avranches, and launched his columns into the rear of the German forces. At this moment, on August 1, General Patton, with Third Army Headquarters, was brought up into the battle to take charge of the operations on the First Army’s right flank.11 Montgomery, at the same time, still confronted by German defenses in depth, shifted his weight from Caen to his right at Caumont and drove for the high ground between the Vire and the Orne.

With a clean and decisive breakout achieved, Bradley’s immediate problem became that of inflicting on the enemy the greatest possible destruction. All else could wait upon his exploitation of this golden opportunity, in the certainty that with the enemy destroyed everything else could quickly be set right. His scheme was to throw every unit he could spare elsewhere directly at the rear of the German forces still in place between Caen and the vicinity of Avranches. In effect, he hoped to encircle the enemy forces, which were still compelled to face generally northward against the Canadians and British.12

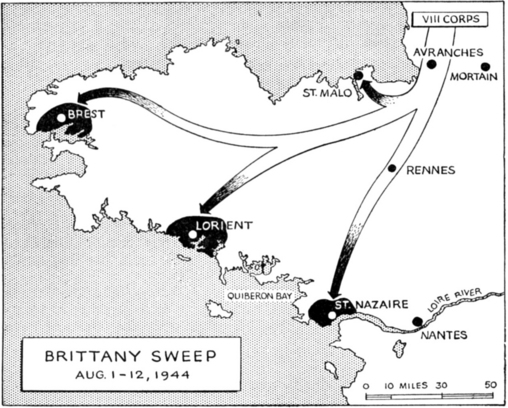

To carry out this general idea, the first change in original plans was in the reduction of the size of the force allocated for the capture of the Brittany Peninsula. Instead of committing to this mission the bulk of the Third Army, General Patton was directed to send back into that area only the VIII Corps, under Major General Troy H. Middleton.13

As the enemy saw the American First Army attack gather momentum to the southward and finally break through the Avranches bottleneck, his reaction was swift and characteristic. Chained to his general position by Hitler’s orders as well as by the paralyzing action of our air forces, he immediately moved westward all available armor and reserves from the Caen area to counterattack against the narrow strip through which American forces were pouring deep into his rear. His attack, if successful, would cut in behind our breakout troops and place them in a serious position. Because our corridor of advance was still constricted the German obviously felt that the risks he was assuming were justified even though, in case of his own failure, the destruction he would suffer would be vastly increased. His attacks, which were thrown in at the town of Mortain, just east of Avranches, began on August 7.14

The air co-operation against the enemy attack was extraordinarily effective. The United States Ninth Air Force and the RAF destroyed hundreds of enemy tanks and vehicles. The Royal Air Force had a large number of Typhoons equipped with rocket-firing devices. These made low-flying attacks against the enemy armor and kept up a sustained assault against his forces that was of great help to the defending infantry.15

Bradley and I, aware that the German counterattack was under preparation, carefully surveyed the situation. We had sufficient strength in the immediate area so that if we chose merely to stand on the defensive against the German attack he could not possibly gain an inch. However, to make absolutely certain of our defenses at Mortain, we would have to diminish the number of divisions we could hurl into the enemy’s rear and so sacrifice our opportunity to achieve the complete destruction for which we hoped. Moreover, by this time the weather had taken a very definite turn for the better and we had in our possession an Air Transport Service that could deliver, if called upon, up to 2000 tons of supplies per day in fields designated by any of our forces that might be temporarily cut off.

When I assured Bradley that even under a temporary German success he would have this kind of supply support, he unhesitatingly determined to retain only minimum forces at Mortain, and to rush the others on south and east to begin an envelopment of the German spearheads. I was in his headquarters when he called Montgomery on the telephone to explain his plan, and although the latter expressed a degree of concern about the Mortain position, he agreed that the prospective prize was great and left the entire responsibility for the matter in Bradley’s hands. Montgomery quickly issued orders requiring the whole force to conform to this plan, and he, Bradley, and Lieutenant General Miles Dempsey, commanding the British Second Army, met to co-ordinate the details of the action.16

Another factor that justified this very bold decision was the confidence that both Bradley and I had now attained in our principal battle commanders. In Patton, who took command of the Third Army on the right immediately after the breakout was achieved, we had a great leader for exploiting a mobile situation. On the American left we had sturdy and steady Hodges to continue the pressure on the Germans, while in both armies were battle-tested corps and division commanders. They could be depended upon in any situation to act promptly and effectively without waiting for detailed instructions from above.

Bradley’s judgment as to his ability to hold the Mortain hinge was amply demonstrated by events but the whole situation is yet another example of the type of delicate decision that a field commander is frequently called upon to make in war. Had the German tanks and infantry succeeded in breaking through at Mortain, the predicament of all troops beyond that point would have been serious, in spite of our ability partially to supply them by airplane. While there was no question in our minds that we could eventually turn the whole thing into a victory even if the German should succeed temporarily in this interruption of our communications, yet had the enemy done so the necessary retrograde movements of our own troops and the less satisfactory results achieved would have undoubtedly been publicly characterized as a lost battle.

There were many points of similarity between this situation and the one that developed some four months later in the Ardennes, which resulted in the Battle of the Bulge. In both cases our long-term calculations proved correct but in the one the German achieved temporary success, while at Mortain he was repulsed immediately and materially added to the severity of his own battle losses.

The enemy concentrated the bulk of his available armor at Mortain and continued his obstinate attack until August 12. By this time Bradley’s planned movements were developing satisfactorily.

On General Bradley’s directive, General Patton had sent the XV Corps, commanded by Major General Wade H. Haislip, straight southward to the town of Laval. East of Laval it turned north on Argentan. The XII Corps, under command of Major General Gilbert R. Cook, was ordered to advance on Orléans on the Third Army’s south flank; and the XX Corps, commanded by Major General Walton H. Walker, was directed on Chartres. Later, the XIX Corps, under Major General Charles H. Corlett, also participated in the envelopment. The Canadian First Army was directed by Montgomery to continue to thrust southward on Falaise with a view to linking up with the Americans at Argentan, to close the net around the enemy forces still west of that point. Meanwhile the U. S. First Army and the British Second Army would both drive toward the trapped Germans to accomplish their rapid destruction.17

The enveloping movement from the south therefore had as its first objective the destruction or capture of the German forces in the Mortain–Falaise region, while at the same time there remained the opportunity for sweeping up remaining portions of the German First and Seventh Armies by directing an even wider employment toward the crossings of the Seine River. The operation assumed this over-all picture: Montgomery’s army group was attacking generally southward against the old Normandy beachhead defenses, while Bradley’s forces, with their left anchored near the position of the initial break-through, were carrying out the great envelopments intended to trap the entire German force still between his marching columns and the front of the British Twenty-first Army Group. In the meantime the Allied air forces kept up an incessant battering against any possible crossings of the Seine so as to impede the escape of any German forces that might try to cross to the north of that river before the trap could be closed. Perfection of co-ordination in such an operation is difficult to achieve.

By the night of August 13, the U. S. 5th Armored Division under General Oliver, a veteran of the African campaign, was in the outskirts of Argentan. The French 2d Armored Division under General Jacques LeClerc was near by and the U. S. 79th and 90th Divisions were in close support. The Germans were still fighting desperately just south of Caen, where by this time they had established the strongest defenses encountered throughout the entire campaign.18 The Canadians threw in fierce and sustained attacks but it was not until August 16 that Falaise was finally captured. Caen, by then a heap of rubble, had been captured on July 9.19

By late July the enemy was bringing reinforcements across the Seine as rapidly as he could. Five divisions entered the battle area during the week August 5–12 but, as before, they were unable to affect the outcome.

On August 13, I sent a personal message to the Allied command that, in part, read:

Because this opportunity may be grasped only through the utmost in zeal, determination and speedy action, I make my present appeal to you more urgent than ever before.

I request every airman to make it his direct responsibility that the enemy is blasted unceasingly by day and by night, and is denied safety either in fight or in flight.

I request every sailor to make sure that no part of the hostile forces can either escape or be reinforced by sea, and that our comrades on the land want for nothing that guns and ships and ships’ companies can bring to them.

I request every soldier to go forward to his assigned objective with the determination that the enemy can survive only through surrender: let no foot of ground once gained be relinquished nor a single German escape through a line once established.20

With the great bulk of all the Allied forces attacking from the perimeter of a great half-circle toward a common center, the determination of the exact points on which each element should halt, in order not to become involved against friendly units coming from the opposite direction, was a tricky problem.

In this instance Bradley’s troops, marching in the great wheel, had much farther to go to close the trap than did the British and Canadian troops. On the other hand, the latter were still faced up against prepared defenses and their movement was limited to the advances they could make through heavily defended areas. Montgomery kept in close touch with the situation but so rapid was the movement of the Americans that it was almost impossible to achieve the hour-by-hour co-ordination that might have won us a complete battle of annihilation.

Mix-ups on the front occurred, and there was no way to halt them except by stopping troops in place, even at the cost of allowing some Germans to escape. In the aggregate considerable numbers of Germans succeeded in getting away. Their escape, however, meant an almost complete abandonment of their heavy supply and was accomplished only by terrific sacrifices.

I was in Bradley’s headquarters when messages began to arrive from commanders of the advancing American columns, complaining that the limits placed upon them by their orders were allowing Germans to escape. I completely supported Bradley in his decision that it was necessary to obey the orders, prescribing the boundary between the army groups, exactly as written; otherwise a calamitous battle between friends could have resulted.

In the face of complete disaster the enemy fought desperately to hold open the mouth of the closing pocket so as to save as much as he could from the debacle. German commanders concentrated particularly on saving armored elements, and while a disappointing portion of their Panzer divisions did get back across the Seine, they did so at the cost of a great proportion of their equipment. Eight infantry divisions and two Panzer divisions were captured almost in their entirety.

The battlefield at Falaise was unquestionably one of the greatest “killing grounds” of any of the war areas. Roads, highways, and fields were so choked with destroyed equipment and with dead men and animals that passage through the area was extremely difficult. Forty-eight hours after the closing of the gap I was conducted through it on foot, to encounter scenes that could be described only by Dante. It was literally possible to walk for hundreds of yards at a time, stepping on nothing but dead and decaying flesh.

In the wider sweep directed against the crossings of the Seine behind the German Army, the rapidly advancing Americans were also forced to halt to avoid overrunning their objectives and firing into friendly troops. The German again seized the opportunity to escape with a greater portion of his strength than would have been the case if the exact situation could have been completely foreseen.21

While the bulk of Bradley’s forces was engaged in these great battles and overrunning France toward Paris, General Middleton’s VIII Corps turned back to the westward to overrun the Brittany Peninsula and to capture the ports in that area. We were still of the belief that some use would have to be made of Quiberon Bay and possibly of Brest. Middleton was directed to capture these places as quickly as possible. He made a rapid advance and invested St. Malo, a small port on the north coast of the Brittany Peninsula. The garrison resisted fanatically but Middleton was able, with co-operating air and naval forces, to bring to bear enough power to reduce it by August 14, although remnants of the garrison held out for three more days in the citadel of the town. Middleton then pushed on to the westward and reached the vicinity of Brest. The commander of the German garrison there was named Ramcke, a formidable fighter.

Middleton vigorously prosecuted the siege but the defenses were strong and the garrison was determined. Any attempt to capture the place in a single assault would be extremely costly to us. Fortunately our prospects for securing better ports than Brest began to grow much brighter just after the middle of August, and in any event we had never counted on the use of that place so much as we had on Quiberon Bay. In these circumstances Middleton was directed to avoid heavy losses in the Brest area but was also directed to continue the pressure until the garrison should surrender.22

I visited him during the conduct of the siege and surveyed the defenses that we would have to overcome. He skillfully kept up a series of attacks, each designed to minimize our own losses but constantly to crowd the enemy back into a more restricted area, where he was intermittently subjected to bombing by our aircraft.

In the garrison was a contingent of German SS troops. Instead of concentrating them as a unit, General Ramcke distributed them among all other German formations in the defenses. In this way he used the fanaticism of the SS troopers to keep the entire garrison fighting desperately, because at any sign of weakening an SS trooper would execute the offender on the spot.

Brest fell on September 19. The harbor and its facilities had been so completely wrecked by our bombing and by German demolitions that we never made any attempt to use it.23

When the Allied armies finally completed their envelopment of the German forces west of the Seine the eventual defeat of the German in western Europe was a certainty. The question of time alone remained. A danger, however, that immediately presented itself was that our own populations and their governments might underrate the task still to be accomplished, and so might slacken the home-front effort, which could have the gravest consequences. I not only brought this danger to the attention of my superiors, but as early as August 15 held a press conference, predicting that there was one more critical task remaining to the Allied forces—the destruction of the German armies along the general line of the Siegfried and the Rhine.24 This word of caution was swept away in the general rejoicing over the great victory, and even among the professional leaders of the fighting forces there grew an optimism, almost a lightheartedness, that failed to look squarely in the face such factors as the fanaticism of great portions of the German Army and the remaining strength of a nation that was inspired to desperate action, if by no other means than the Gestapo and Storm Troopers, who were completely loyal to their master, Hitler.

Our new situation brought up one of the longest-sustained arguments that I had with Prime Minister Churchill throughout the period of the war. This argument, beginning almost coincidentally with the break-through in late July, lasted throughout the first ten days of August. One session lasted several hours. The discussions involved the wisdom of going ahead with Anvil, by then renamed Dragoon, the code name for the operation that was to bring in General Devers’ forces through the south of France.

One of the early reasons for planning this attack was to achieve an additional port of entry through which the reinforcing divisions already prepared in America could pour rapidly into the European invasion. The Prime Minister held that we were now assured of early use of the Brittany ports and that the troops then in the Mediterranean could be brought in via Brittany, or even might better be used in the prosecution of the Italian campaign with the eventual purpose of invading the Balkans via the head of the Adriatic.25

To any such change I was opposed, and since the United States Chiefs of Staff, following their usual practice, declined to interfere with the conclusions of the commander in the field, I instantly became the individual against whom the Prime Minister directed all his argument. In brief he advanced the following points:

We no longer had any need of the port of Marseille and the line of communication leading northward from it. Troops in America could come in via Brittany.

The attack through the south of France was so far removed geographically from the troops in northern France that there was no tactical connection between them.

The troops to be used under General Devers in the southern invasion would have more effect in winning the war by driving forward in Italy and into the Balkans and threatening Germany from the south than they would by pursuing the originally planned line of action.

Our entry into the Balkans would encourage that entire region to flame into open revolt against Hitler and would permit us to carry to the resistance forces arms and equipment which would make the efforts of these forces more effective.

My own stand was defined generally as follows:

Experience of the past proved that we were likely to be vastly disappointed in the usefulness of the Brittany ports. Not only did we expect them to be stubbornly defended but we were certain they would be effectively destroyed once we had captured them. We did not expect this destruction to be so marked at Marseille because we knew that a large portion of the defending forces had already been drawn northward to meet our attacks. Capture should be so swift as to allow little time for demolition.

The distance from Brest to the Metz region was greater than the distance from Marseille to Metz. The railway lines connecting the two former points were much more tortuous and were more easily damaged than was the case with regard to the lines up the Rhone River.

Unless Marseille were captured, we would be unable to speed up the arrival of American divisions from the homeland.

The entry of a sizable force into southern France provided definite tactical and strategic support to our own operation.

First, it would protect and support the right flank as we continued our advance toward the heart of the German resistance. Secondly, by joining it to our own right flank we would automatically cut off all regions westward of that point, capture the enemy troops remaining back of the point of junction, and free all of France to assist us both passively and actively.

Without the Dragoon attack we would have to protect our right flank all the way from the base of the Brittany Peninsula to the most forward point of our attacking spearheads. This would have meant the immobilization of large numbers of divisions, stationed along the right merely to insure our own safety against raids by small mobile forces. These defending divisions could scarcely have participated in later aggressive action.

As yet we had secured as a permanent port only Cherbourg. The lines leading out of it were entirely incapable of maintaining our fighting forces along the front. Our maintenance and administrative position would never be equal to the final conquest of Germany until we had secured Antwerp on the north and Marseille or equivalent port facilities on our right. Once we had accomplished this, I was certain, we could marshal on the borders of Germany a sufficient strength, both in troops and in supplies, to launch final and decisive offensives that would knock Germany completely out of the war. Without such facilities we would inevitably outrun our maintenance capacity. We would then find ourselves in a position such as the British had so often experienced in their advances westward from Egypt, an experience that was repeated by Rommel when he finally attained the El Alamein line and was then unable to exploit his advantage.

Another factor was that the American Government had gone to great expense to equip and supply a number of French divisions. These troops naturally wanted to fight in the battle for the liberation of France. At no other point would they fight with the same ardor and devotion, and nowhere else could they obtain needed replacements for battle losses. These troops were located in Italy and North Africa, and the only way they could be brought quickly into the battle was through the opening in the south of France.

I firmly believed that the greatest possible concentration of troops should be effected on the great stretch between Switzerland and the North Sea, whence we would most quickly break into the heart of Germany and join up eventually with the Red forces advancing from the east.26

In sustaining his argument, the Prime Minister pictured a bloody prospect for the forces attacking from the south. He felt sure they would be involved for many weeks in attempts to reduce the coastal defenses and feared they could not advance as far northward as Lyon in less than three months. He thought we would suffer great losses and insisted that the battlefield in that region would become merely another Anzio. It is possible the Prime Minister did not credit the authenticity of our Intelligence reports, but we were confident that few German forces other than largely immobile divisions remained in the south. Consequently we were sure that the German defensive shell would be quickly pierced and that Devers’ troops would pour northward at a rapid pace.

Although I never heard him say so, I felt that the Prime Minister’s real concern was possibly of a political rather than a military nature. He may have thought that a postwar situation which would see the Western Allies posted in great strength in the Balkans would be far more effective in producing a stable post-hostilities world than if the Russian armies should be the ones to occupy that region. I told him that if this were his reason for advocating the campaign into the Balkans he should go instantly to the President and lay the facts, as well as his own conclusions, on the table. I well understood that strategy can be affected by political considerations, and if the President and the Prime Minister should decide that it was worth while to prolong the war, thereby increasing its cost in men and money, in order to secure the political objectives they deemed necessary, then I would instantly and loyally adjust my plans accordingly. But I did insist that as long as he argued the matter on military grounds alone I could not concede validity to his arguments.

I felt that in this particular field I alone had to be the judge of my own responsibilities and decisions. I refused to consider the change so long as it was urged upon military considerations. He did not admit that political factors were influencing him, but I am quite certain that no experienced soldier would question the wisdom, strictly from the military viewpoint, of adhering to the plan for attacking southern France.27

As usual the Prime Minister pursued the argument up to the very moment of execution. As usual, also, the second that he saw he could not gain his own way, he threw everything he had into support of the operation. He flew to the Mediterranean to witness the attack and I heard that he was actually on a destroyer to observe the supporting bombardment when the attack went in.

In this long and serious argument the Prime Minister was supported by certain members of his staff. On the other hand, British officers assigned to my own headquarters stood firmly by me throughout.

Although in the planning days of early 1944, Montgomery had advocated the complete abandonment of the southern operation in order to secure more landing craft for Overlord, he now, in early August, agreed with me that the attack should go in as planned.

Coincidentally with this drawn-out discussion, Montgomery suddenly proposed to me that he should retain tactical co-ordinating control of all ground forces throughout the campaign. This, I told him, was impossible, particularly in view of the fact that he wanted to retain at the same time direct command of his own army group. To my mind and to that of my staff the proposition was fantastic. The reason for having an army group commander is to assure direct, day-by-day battlefield direction in a specific portion of the front, to a degree impossible to a supreme commander. It is certain that no one man could perform this function with respect to his own portion of the line and at the same time exercise logical and intelligent supervision over any other portion. The only effect of such a scheme would have been to place Montgomery in position to draw at will, in support of his own ideas, upon the strength of the entire command.

A supreme commander in a situation such as faced us in Europe cannot ordinarily give day-by-day and hour-by-hour supervision to any portion of the field. Nevertheless, he is the one person in the organization with the authority to assign principal objectives to major formations. He is also the only one who has under his hand the power to allot strength to the various major commands in accordance with their missions, to arrange for the distribution of incoming supply, and to direct the operations of the entire air forces in support of any portion of the line. The existence, therefore, of any separate ground headquarters between the supreme commander and an army group commander would have placed such a headquarters in an anomalous position, since it would have had the power neither to direct the flow of supply and reinforcement nor to give instructions to the air forces for the application of their great power.

Modern British practice had been, however, to maintain three commanders in chief, one for air, one for ground, one for navy. Any departure from this system seemed to many inconceivable and to invite disaster. I carefully explained that in a theater so vast as ours each army group commander would be the ground commander in chief for his particular area; instead of one there would be three so-called commanders in chief for the ground and each would be supported by his own tactical air force. Back of all would be the power of the supreme commander to concentrate the entire air forces, including the bomber commands, on any front as needed, while the strength of each army group would be varied from time to time depending on the importance of enemy positions to the progress of the whole force.

While my decision was undoubtedly distasteful to individuals who had been raised in a different school, it was accepted. In different form the question was raised at a later stage of the campaign, but the decision was always the same.28

In spite of such occasional differences of conviction, there was in our day-by-day operations, month after month, a degree of teamwork and intensive co-operation that made incidents such as I have described exceptional. When these exceptions arose they had to be thrashed out firmly and decisively and an answer given. The wonder is that so few of them ever became of a serious nature.

Field Marshal Montgomery, like General Patton, conformed to no type. He deliberately pursued certain eccentricities of behavior, one of which was to separate himself habitually from his staff. He lived in a trailer, surrounded by a few aides. This created difficulties in the staff work that must be performed in timely and effective fashion if any battle is to result in victory. He consistently refused to deal with a staff officer from any headquarters other than his own, and, in argument, was persistent up to the point of decision.

The harm that this practice could have created was minimized by the presence in the Twenty-first Army Group of a chief of staff who had an enviable reputation and standing in the entire Allied Force. He was Major General Francis de Guingand, “Freddy” to all his associates in SHAEF and in other high headquarters. He lived the code of the Allies and his tremendous capacity, ability, and energy were always devoted to the co-ordination of plan and detail that was absolutely essential to victory.

Montgomery is best described by himself in a letter he wrote to me shortly after the victory was won in Europe. He said:

Dear Ike:

Now that we have all signed in Berlin I suppose we shall soon begin to run our own affairs. I would like, before this happens, to say what a privilege and an honor it has been to serve under you. I owe much to your wise guidance and kindly forbearance. I know my own faults very well and I do not suppose I am an easy subordinate; I like to go my own way.

But you have kept me on the rails in difficult and stormy times, and have taught me much.

For all this I am very grateful. And I thank you for all you have done for me.

Your very devoted friend,

Monty29

In my reply I said, with complete truth:

Your own high place among military leaders of your country is firmly fixed, and it has never been easy for me to disagree with what I knew to be your real convictions. But it will always be a great privilege to bear evidence to the fact that whenever decision was made, regardless of your personal opinion, your loyalty and efficiency in execution were to be counted upon with certainty.30

Another interesting, if less pressing, discussion took place with Secretary Morgenthau. In a visit to our headquarters in early August 1944 he said that the rate of monetary exchange, to be eventually established in Germany, should be such as to avoid giving that country any advantage. I candidly told him that I had been far too busy to be specifically concerned with the future economy of Germany but that I had an able staff section working on the problem. This brought about a general conversation on the subject of Germany’s future and I expressed myself roughly as follows.

“These things are for someone else to decide, but my personal opinion is that, following upon the conclusion of hostilities, there must be no room for doubt as to who won the war. Germany must be occupied. More than this, the German people must not be allowed to escape a sense of guilt, of complicity in the tragedy that has engulfed the world. Prominent Nazis, along with certain industrialists, must be tried and punished. Membership in the Gestapo and in the SS should be taken as prima facie evidence of guilt. The General Staff must be broken up, all its archives confiscated, and members suspected of complicity in starting the war or in any war crime should be tried. The German nation should be responsible for reparations to such countries as Belgium, Holland, France, Luxembourg, Norway, and Russia. The warmaking power of the country should be eliminated. Possibly this could be done by strict controls on industries using heavy fabricating machinery or by the mere expedient of preventing any manufacture of airplanes. The Germans should be permitted and required to make their own living, and should not be supported by America. Therefore choking off natural resources would be folly.”

I emphatically repudiated one suggestion I had heard that the Ruhr mines should be flooded. This seemed silly and criminal to me. Finally, I said that the military government of Germany should pass from military to civil hands as quickly as this could be accomplished.

These views were presented to everyone who queried me on the subject, both then and later. They were eventually placed before the President and the Secretary of State when they came to Potsdam in July 1945.