ALL DURING THE BATTLE OF THE BULGE WE continued to plan for the final offensive blows which, once started, we intended to maintain incessantly until final defeat of Germany. Operations were planned in three general phases, beginning with a series of attacks along the front to destroy the German armies west of the Rhine. The next phase would comprise the crossing of that river and establishment of major bridgeheads. Thereafter we would initiate the final advances that we were sure would carry us into the heart of Germany and destroy her remaining power to resist.1

Somewhere during this final advance we would meet portions of the Red Army coming from the east and it now became important to arrange closer co-ordination with the activities of the Red Army. During earlier campaigns we had been kept informed of the general intentions of the Soviet forces by the Combined Chiefs of Staff. This provided sufficient co-ordination between the two forces so long as the two zones of operations were widely separated. Now, however, the time had come to exchange information of plans as to objectives and timing.

In early January 1945, with the approval of the Combined Chiefs of Staff, I sent Air Chief Marshal Tedder to Moscow to make necessary arrangements for this co-ordination. He was accompanied by Major General Harold R. Bull and Brigadier General T. J. Betts, two able American officers from the SHAEF staff. Air Chief Marshal Tedder was authorized to give the Russian military authorities full information concerning our plans for the late winter and spring, and was to obtain similar information concerning Russian projects.2

We already knew that the Russians were contemplating an early westward attack from their positions around Warsaw, on the Vistula. We understood that the Russians had effected concentrations for an offensive by the first of the year, but because of conditions of terrain and, more particularly, because of thick blankets of fog and cloud that interfered with air operations, they were holding up the attack until conditions should be more favorable. We learned through the Combined Chiefs of Staff, however, that even if these conditions failed to show improvement the Russian attack would be launched no later than January 15. It began on January 12 and made remarkable progress.

Air Chief Marshal Tedder and his associates arrived in Moscow just after this attack began. The Generalissimo and the Russian military authorities received them with the utmost cordiality and there was a full and accurate exchange of information concerning future plans. The Generalissimo informed our mission that even if the attacks then in progress should fail to reach their designated objectives the Russians would keep up a series of continuous operations that would, at the very least, prevent the German from reinforcing the western front by withdrawing forces from the Russian zone.3

As a further result of this initial effort the Combined Chiefs of Staff authorized me to communicate directly with Moscow on matters that were exclusively military in character. Later in the campaign my interpretation of this authorization was sharply challenged by Mr. Churchill, the difficulty arising out of the age-old truth that politics and military activities are never completely separable.4

In modern war the need for co-ordination between two friendly forces that are attacking toward a common center is far more acute than it was in the days when fighting was confined to the ground, along a narrow band of territory defined by the range of small arms and field guns. Today the fighter bombers supporting an attacking army constantly range over the enemy lines, sometimes hundreds of miles in his rear. Their purpose is to find and destroy hostile headquarters, dumps, depots, and bridges and to attack reserve formations. Long before the two friendly armies themselves can make contact there arises a delicate problem in co-ordination to prevent unfortunate accidents and misunderstandings between allied but separated forces.

Recognition of friend or foe on the battlefield is never easy. In our own War Between the States, where one side was clad in blue and the other in gray, more than one sharp fight took place between units of the same army. In modern war, where all uniforms are designed with the idea of blending with the countryside, where the mass formations of the nineteenth century are never seen, and where the speeds of airplanes and vehicles afford observers only a fleeting instant for decisive action, the problem is difficult to solve. These matters would demand more and more detailed attention as our advance progressed. But in January 1945 we needed primarily to know the timing and direction of the next Russian attack and to lay the groundwork that would permit future battlefield co-operation.

By early 1945 the effects of our air offensive against the German economy were becoming catastrophic. Our great land advances had effectively disrupted the enemy’s air warning and defense system and had overrun many places—particularly the western European ports where submarine nests were located—which had formerly diverted much of our bombing effort from targets in the heart of Germany. Another advantage that our strategic bombers now enjoyed was better protection from accompanying fighters. Groups of fighters could be located at forward fields near the Rhine and, in spite of their comparatively short range, could operate over almost any target in Axis territory.

By this time also the air had achieved remarkable success in depleting the German oil reserves. For many months the enemy’s oil resources had been one of the principal objectives of strategic bombing and as the effects of this offensive accumulated there developed a continuous crisis in German transportation and in all phases of her war effort. It had a definite influence upon the ground battles. Germany found it increasingly difficult to transfer reserve troops and supplies from one front to another, while her troops in every sector were constantly embarrassed by lack of fuel for vehicles. The effect was felt also by the Luftwaffe, in which training of new pilots had to be sharply curtailed because of fuel shortage.5

During the long winter fighting our Intelligence staffs began to bring us disturbing information that the Germans were making great progress in the development of jet airplanes. Our air commanders were of the opinion that if the enemy could succeed in putting these planes into the air in considerable numbers he would quickly begin to exact insupportable losses from our bombers operating over Germany. Our own development of jet planes was progressing in the United States and in Great Britain but we were not yet far enough along to count on squadrons of them during the spring campaign.

Our only possible recourse was to attempt by our bombing effort to delay German production of this new weapon. The air forces knew that extra-long runways were required for the employment of the jet plane and whenever they found a German field with such a runway they kept it under intermittent but repeated bombardment. In addition they sought out every area where they believed these planes were under construction. This caused some diversion from our objective of depleting oil reserves but by January 1945 we had such air strength and efficiency that we could afford it without material damage to our primary mission. The effect of our bombing effort against jet production was at least partially successful because the German never succeeded in employing a sufficient number of the new planes to damage us materially.6

Information concerning all these things was gathered by our Intelligence services, which daily presented to me their calculations and conclusions. These emphasized the mounting difficulties of the German war machine and encouraged me and all my associates to believe that one more great campaign, aggressively conducted on a broad front, would give the death blow to Hitler Germany.

I found, among some of the higher military officials of Britain, a considerable and, to me, surprising opposition to my plan.

The relationship maintained by the American Chiefs of Staff with their commanders in the field differed markedly from that which existed between similar echelons in the British service. The American doctrine has always been to assign a theater commander a mission, to provide him with a definite amount of force, and then to interfere as little as possible in the execution of his plans. The theory is that the man in the field knows more of the tactical situation than someone removed by several thousand miles from the scene of action; and that if results obtained by the field commander become unsatisfactory the proper procedure is not to advise, admonish, and harass him, but to replace him by another commander.

On the other hand, the British Chiefs in London maintained throughout the war the closest kind of daily contact with their own commanders in the field and insisted upon being constantly informed as to details of strength, plans, and situation. This habit may have been based upon sound reasons of which I knew nothing, but it was always a shock to me, raised in the tradition of the American services, to find that the British Chiefs regularly queried their commanders in the field concerning tactical plans. For example, the British commander was required to submit to London a daily report covering every item of information that in our service would only in exceptional circumstances go higher than a local army headquarters.

My own practice throughout the war was merely to submit to Washington and London brief daily situation reports called “Cositintreps” (combined situation and intelligence reports).

When I completed my final plan in January 1945 my friend Field Marshal Brooke informally but very earnestly presented serious objections. His questions were directed against what he called the planned dispersion of our forces. He maintained that we would never have enough strength to mount more than one full-blooded attack across the Rhine. Consequently, he said, in order to assure ourselves of the strength to sustain such an attack we should, as the situation then stood, pass to the defensive on all other parts of the line.7

Dispersion is one of the greatest crimes in warfare, but as with all other generalities the proper application of the truth is far more important than mere knowledge of its existence.

In the situation facing us in January, the German enjoyed the great advantage of the Siegfried defenses in the area northward from the Saar, inclusive. As long as we allowed him to remain in those elaborate fortifications his ability was enhanced to hold great portions of his long line with relatively weak forces, while he concentrated for spoiling attacks at selected points. This meant that a large proportion of the Allied Force would be immobilized in a protective role, with only that portion on the offensive that could be maintained north of the Ruhr. In that single zone of advance we could not logistically sustain more than thirty-five divisions.8

If, however, we should first, in a series of concentrated and powerful attacks, destroy the German forces west of the Rhine, the effect would be to give us all along the great front a defensive line of equal strength to the enemy’s. We calculated that with the western bank of the Rhine in our possession we could hurl some seventy-five reinforced divisions against the German in great converging attacks. If we allowed the enemy south of the Ruhr to remain in the Siegfried, we would be limited to a single offensive by some thirty-five divisions.

A second advantage of our plan would be the depletion of the German forces later to be met at the crossings of the Rhine obstacle. Moreover, the effect of the converging attack is multiplied when it is accompanied by such air power as we had in Europe in the early months of 1945. Through its use we could prevent the enemy from switching forces back and forth at will against either of the attacking columns and we could likewise employ our entire air power at any moment to further the advance in any area desired.

I laboriously explained to Field Marshal Brooke that, far from dispersing effort, I was conducting the campaign so that when we were ready to initiate the final invasion of Germany on the other side of the Rhine we could bring such a concerted and tremendous power against him that his collapse would quickly follow. The decisive advantage in gaining the Rhine River along its length was to increase drastically the proportion of the Allied forces that could be used offensively.

I did not wholly convince him. He said, “I wish that the Twelfth Army Group were deployed north of the Ruhr and the British forces were in the center,” implying that my plans were drawn up on nationalistic considerations.

To this I retorted: “I am certainly no more anxious to put Americans into the thick of the battle and get them killed than I am to see the British take the losses. I have strengthened Montgomery’s army group by a full American army, since in no other way can I provide the strength north of the Ruhr that I deem essential for the rapid execution of my plans. I have not devised any plan on the basis of what individual or what nation gets the glory, for I must tell you in my opinion there is no glory in battle worth the blood it costs.”

Field Marshal Brooke expressed the hope that things would work out as I believed they would; but he was apparently doubtful of Allied ability to destroy the German forces between us and the Rhine River by a succession of crushing blows.

At the same time there was again suggested to me the establishment of an over-all “ground commander” to operate directly under SHAEF. I repudiated this suggestion, as I always had before. I was certain that our plans for the completion of the German defeat were the best that could be devised. Entirely aside from my feeling that the proposed arrangement would be futile and clumsy, I was determined to prevent any interference with the exact and rapid execution of those plans.9

In early January, I learned that the President, the Prime Minister, and their staffs were again to meet with Generalissimo Stalin, this time at Yalta. General Marshall proceeded separately from the rest of the American group into Europe, and I arranged to meet him secretly at Marseille. I went there on January 25 and we had a long talk about the situation as we then saw it.

In Washington he had heard rumblings of the British Staff’s dissatisfaction with our plans and had also heard the proposal that a single ground commander be set up. I explained our situation and outlined the exact steps by which we planned the defeat of Germany. He was in full agreement.10

At that time, however, there was one miscalculation in our plans, based upon faulty technical information. The engineers had made many studies of the Rhine River, based upon statistics covering a long period. They had reported to me that successful assaults could probably not be made over the Rhine until about the first of May. This opinion was so forcibly expressed that in my own mind I had accepted the necessary delay and was planning not to start our major assaults across the river until about that time. This did not, of course, affect any part of our plans that were to be executed before the time came to cross the river. Later our technical advice on this point was markedly changed and we found that it was feasible to cross the river, establish bridges, and maintain ourselves long before the first of May.

General Marshall was so impressed by the soundness of the whole plan that he suggested I send my chief of staff, General Smith, to Malta to participate in a conference that was to take place there between the President, the Prime Minister, and their respective staffs before they went on to Yalta. He remarked: “I can, of course, uphold your position merely on the principle that these decisions fall within your sphere of responsibility. But your plan is so sound that I think it better for you to send General Smith to Malta so that he may explain these matters in detail. Their logic will be convincing.”11 I was glad to agree because I well knew that with General Marshall backing me up there would be no danger of interference with our developing plans.

Field Marshal Brooke’s arguments in the matter were founded in conviction. There was no petty basis for his great concern. This was proved by the fact that only a few weeks later, when the destruction of the German armies west of the Rhine had been accomplished and he stood with me on the banks of the river to witness the crossing by the Ninth Army and the Twenty-first Army Group, he turned to me and said: “Thank God, Ike, you stuck by your plan. You were completely right and I am sorry if my fear of dispersed effort added to your burdens. The German is now licked. It is merely a question of when he chooses to quit. Thank God you stuck by your guns.”12

The operational schedule for the first phase of our strategic plan—destruction of the enemy strength west of the Rhine—contemplated three major assaults. The first would be by the Twenty-first Army Group at the northern flank of our lines; the second, by Bradley’s group in the center; and the third, a converging attack by Bradley and Devers to eliminate the enemy garrison in the Saar Basin.

As soon as the First and Third Armies had joined forces at Houffalize on January 16, 1945, Montgomery returned to specific preparation for the first of these three attacks.13 West of the Rhine the Siegfried Line extended southward from the confluence of that river with the Maas, down to include the defenses of the Saar Basin. Immediately south of the Saar a few German detachments remained in the Alsace plain, while farther south we were plagued by the Colmar pocket.

In January, with the Germans recoiling from their disastrous adventure in the Ardennes, I turned my attention again to Colmar. The existence of this German position in a sensitive part of our lines had always irritated me and I determined that it was to be crushed without delay. The French First Army began attacks against it on the twentieth of January but these, handicapped by bad weather, made little progress. There were two French corps surrounding the pocket, but in my determination to get rid of this annoyance once and for all I gave additional strength to Devers so that he could support the French with an entire United States corps of four divisions. He assigned the XXI Corps under Major General Frank W. Milburn to the task, with the 3d, 28th, and 75th Infantry Divisions and the French 5th Armored Division. Later the 12th Armored Division and French 2d Armored Division were also used in the XXI Corps zone. With the American corps as the spearhead, the two French corps and the American attacked simultaneously. German defenses quickly disintegrated. Colmar surrendered February 3 and by the ninth of the month such Germans as survived in that region had been driven across the Rhine. In this operation the enemy suffered more than 22,000 casualties and heavy losses in equipment.14

In the planned campaign against German forces confronting our units the first attack was to be carried out by the Canadian Army of the Twenty-first Army Group, and the U. S. Ninth Army, temporarily attached to Montgomery. The Canadians were to attack south and southeast across the Maas River, while Simpson’s Ninth Army would cross the Roer to advance northeastward. This would bring a converging effort upon the defending forces and drive them rapidly back to the Rhine.

In this region were some of the best combat troops the enemy had remaining to him. They included his First Paratroop Army, in which men and units had been trained to a high degree of skill and hardihood. An additional difficulty on Simpson’s front was the enemy’s continued possession of the Roer dams, through which he was enabled to prevent successful assault across the Roer River. Bradley therefore ordered Hodges’ First Army to capture the dams at the earliest possible date. The attack against them was launched by the V Corps on February 4. After hard fighting the First Army captured them within six days. Even then our difficulties with the dams were not over because the Germans blocked the spillway gates in such position as to insure that overflow from the reservoirs would keep the river at flood stage for some days.15

As Montgomery began preparing for his offensive he naturally wanted the U. S. Ninth Army built up to the greatest possible strength. He recommended that Bradley be ordered to stop attacking with the First and Third Armies through the Ardennes region so as to save troops for greater concentration farther north. I declined to do this. I was certain that the continued attacks in the Ardennes would tend to keep the enemy’s forces away from the northern sector. More important than this, I was very anxious to push the American lines forward in the Ardennes region so that when the time should come to participate in major destructive attacks the troops would be in excellent position from which to start the move. I was sure that we could gain the line I wanted without interfering with the timely build-up of the Ninth Army.

Montgomery and I agreed on the proper timing for his initial attack. Originally we had wanted to make a simultaneous assault by the Canadians and Americans, both of whom could be ready to attack by February 10. However, neither Montgomery nor I felt it wise to wait until the flood waters of the Roer receded. He proposed, and I approved, that the Canadian attacks should begin as quickly as possible, even if a period of two weeks or more had to intervene before the American Army could join in the operation.16

The Canadian Army jumped off February 8. It made satisfactory initial gains but the troops quickly found themselves involved in a quagmire of flooded and muddy ground and pitted against heavy resistance. Progress was slow and costly and opposition became stiffer as the Germans began moving their forces from the Roer into the path of the Canadian advance. Montgomery was not too displeased by this transfer of German weight because of the promise it held that, once the American attack began, it would advance with great speed.17

I visited General Simpson’s Ninth Army during this period and found it keyed up and well prepared for the attack. If Simpson ever made a mistake as an army commander, it never came to my attention. After the war I learned that he had for some years suffered from a serious stomach disorder, but this I never would have suspected during hostilities. Alert, intelligent, and professionally capable, he was the type of leader that American soldiers deserve. In view of his brilliant service, it was unfortunate that shortly after the war ill-health forced his retirement before he was promoted to four-star grade, which he had so clearly earned.

Simpson’s army comprised three corps. The XVI, under Major General J. B. Anderson, was on the left. On the right was the XIX under Major General Raymond S. McLain. McLain was a National Guard officer who had entered the war as a brigadier general in command of the artillery of the 45th Division. Later he took over the 90th Division during the hard fighting just following the breakout in late July. His leadership of that division was so outstanding that when General Corlett, commanding the XIX Corps, suffered a breakdown in health, McLain was advanced to command of that corps. The center corps of Simpson’s army was the XIII under Major General Alvan C. Gillem, Jr.18

In the days following upon the Canadian attack in the north the Americans could do little except watch the river and be ready to attack as soon as receding floods permitted the bridging of that obstacle. It was two weeks after General Crerar’s Canadians began the attack that this became possible. Simpson set his attack for the morning of the twenty-third.

Preceded by a violent bombardment, the Ninth Army got off as scheduled and succeeded in crossing the river. Initially the troops encountered great difficulties, particularly because of hostile artillery fire upon their floating bridges and because of destruction in the city of Jülich, caused by our aerial and artillery bombardment. The advancing units had to pass through this city, and in order to get vehicles through, it was first necessary to bring up bulldozers to shove a path through the heaps of rubble. Major General Charles H. Gerhardt’s 29th Division, veterans of the Normandy assault in the preceding June, performed splendidly as did the 30th, 102d, and 84th Divisions, also in the initial assault. These three divisions were commanded by Major Generals Leland S. Hobbs, Frank A. Keating, and Alexander R. Bolling respectively. In spite of delays, Simpson’s forces made fine progress, partially as a result of the prior transfer of German forces from this front to the Canadian battlefield. In less than a week the Ninth Army captured München-Gladbach. This was the largest German city we had captured in the war up to this time.

While going into the city with Simpson, shortly after its capture, I saw my first jet plane. It was a German fighter, flying very high. Every anti-aircraft gun in the area immediately opened intensive fire and within a few seconds fragments of exploded shells were dropping around us. For the only time in the war I put on a steel helmet. The alternative was to stop the jeep and get under it for protection. In Africa one of our finest officers had been struck by a falling shell fragment and so severely wounded that he was hospitalized for more than a year. Fortunately the hostile plane found the area uncomfortable and quickly left.

The German forces in the area were now feeling the effect of the powerful converging attack and began to retreat toward the Rhine. By March 3, Simpson’s left corps, the XVI, had swung forward, joined the Canadians, and was driving toward the river. The whole area was rapidly cleared of the enemy. In this battle, because of the proximity of the defending Germans to their bridges over the Rhine, we did not succeed in capturing the same proportions that we did in later assaults.

With the Rhine’s west bank cleared in the northern sector it became Montgomery’s task to prepare, for an early assault across the river. For that operation he would need greater strength than the Twenty-first Army Group could possibly provide. Consequently I directed the Ninth Army to remain attached to him.19 As those forces turned their attention to preparation for the crossing, events to the southward were proceeding remarkably well.

When Simpson began his assault on February 23 it was the signal for Bradley, in the center of our long line, to begin a series of attacks which were brilliantly managed and swiftly conducted. He then had two armies under his operational command, the First on the left, the Third on the right. As a result of the late January and early February fighting along the fronts of these two armies they had secured good positions from which to make a major assault. Bradley’s first move was made by Hodges, who sent forward the VII Corps, the left of his First Army, simultaneously with Simpson’s attack. The first mission of the VII Corps was to support Simpson’s right as the Ninth Army moved to the assault. Success in this move would tend to uncover the right flank of the Germans to the southward and as quickly as this happened the VII Corps was to turn to its right to attack the Germans in flank. The remainder of Hodges’ army, facing eastward, would then take up the assault. Still farther to the south Patton would then begin to attack in the effort to cut off and surround the Germans and to capture or destroy them in place.20

Everything went like clockwork. The VII Corps, on Simpson’s right, was quickly able to begin its southward attacks, and from that moment on success attended us everywhere along the front.

The VII Corps first overcame heavy opposition near the Erft Canal. It continued a spectacular advance and on March 5 was on the outskirts of Cologne. We had calculated that this city would be stubbornly defended, as Aachen had been. However, the hastily trained and astonished defending troops were by no means the equal of those we had met earlier in the campaign. By the afternoon of the seventh of March, Collins had taken over the whole of the city. Since we had estimated that his corps would be engaged there for a period of days in a heavy siege, the quick capture had the effect of providing us with additional divisions to exploit other victories to the south.21

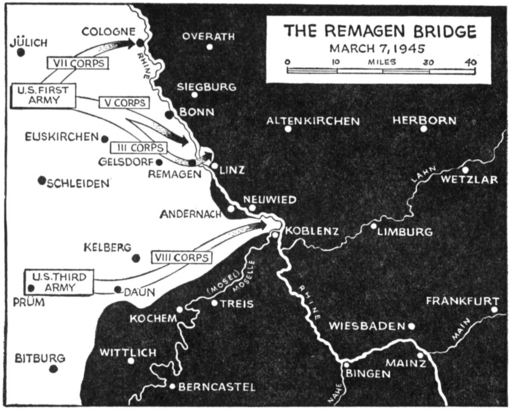

While Collins’ VII Corps was making these great advances Hodges launched the III and V Corps southeastward toward the Rhine. The III Corps reached the river at Remagen on March 7. Here it encountered one of those bright opportunities of war which, when quickly and firmly grasped, produce incalculable effect on future operations. The assaulting Americans found the Ludendorff Bridge over the Rhine was still standing at Remagen.

The Germans had, of course, made elaborate advance preparations to destroy the Rhine bridges. The Ludendorff Bridge was no exception. However, so rapid was the advance of the American troops and so great was the confusion created among the defenders that indecision and doubt overtook the detachment responsible for detonation of the charges under the bridge. Apparently the defenders could not believe that the Americans had arrived in force and possibly felt that destruction of the bridge should be delayed in order to permit withdrawal of German forces which were still west of the river in strength.

The 9th Armored Division, under General Leonard, was leading the advance toward the bridge. Without hesitation a gallant detachment of Brigadier General William M. Hoge’s Combat Command B rushed the bridge and preserved it against complete destruction, although one small charge under the bridge was exploded.22

This news was reported to Bradley. It happened that a SHAEF staff officer was in Bradley’s headquarters when the news arrived, and a discussion at once took place as to the amount of force that should be pushed across the bridge. If the bridgehead force was too small it would be destroyed through a quick concentration of German strength on the east side of the river. On the other hand, Bradley realized that if he threw a large force across he might interfere with further development of my basic plan. Bradley instantly telephoned me.

I was at dinner in my Reims headquarters with the corps and division commanders of the American airborne forces when Bradley’s call came through. When he reported that we had a permanent bridge across the Rhine I could scarcely believe my ears. He and I had frequently discussed such a development as a remote possibility but never as a well-founded hope.

I fairly shouted into the telephone: “How much have you got in that vicinity that you can throw across the river?”

He said, “I have more than four divisions but I called you to make sure that pushing them over would not interfere with your plans.”

I replied, “Well, Brad, we expected to have that many divisions tied up around Cologne and now those are free. Go ahead and shove over at least five divisions instantly, and anything else that is necessary to make certain of our hold.”

His answer came over the phone with a distinct tone of glee: “That’s exactly what I wanted to do but the question had been raised here about conflict with your plans, and I wanted to check with you.”

That was one of my happy moments of the war. Broad success in war is usually foreseen by days or weeks, with the result that when it actually arrives higher commanders and staffs have discounted it and are immersed in plans for the future. This was completely unforeseen. We were across the Rhine, on a permanent bridge; the traditional defensive barrier to the heart of Germany was pierced. The final defeat of the enemy, which we had long calculated would be accomplished in the spring and summer campaigning of 1945, was suddenly now, in our minds, just around the corner.

My guests at the dinner table were infected by my enthusiasm. Among them were veterans of successful aerial jumps against the enemy and of hard fighting in every kind of situation. They were unanimous in their happy predictions of an early end to the war. I am sure that from that moment every one of them went into battle with the élan that comes from the joyous certainty of smashing victory.

By March 9 the First Army had enlarged the Remagen bridgehead area until it was more than three miles deep. It took the enemy a considerable time to recover from his initial surprise and confusion, and by the time he could bring up reinforcements against our bridgehead troops we were too strong to fear defeat. As usual the enemy attacked piecemeal with every unit as soon as it could arrive in the area but such feeble tactics were unable to combat our steady enlargement of the hold we had on his vitals.

From the day we crossed the river the enemy initiated desperate efforts to destroy the Ludendorff Bridge. Long-range artillery opened fire on it and the German Air Force concentrated every available plane for bombing attacks upon the structure. None of these was immediately successful and we continued to pour troops across the bridge, but at the same time we established floating Treadway bridges.

The Treadway bridge was one of our fine pieces of equipment, capable of sustaining heavy military loads. It was comparatively easy to transport and was quickly installed. After General Collins and his VII Corps crossed the Rhine he was of course concerned with getting his floating bridges established as quickly as possible. He called in his corps engineer, Colonel Mason J. Young, and said: “Young, I believe you can put a bridge across this river in twelve hours. What kind of a prize do you want me to give you for doing it in less time than that?” Young reflected a second and then said, “I don’t want anything but if you can promise a couple of cases of champagne to my men we shall certainly try to win them.” “All right,” said Collins, “I’ll get the champagne if you get me a bridge in less than twelve hours.”

In ten hours and eleven minutes the 330-yard bridge was completed and the first load crossed the river.23 Collins gladly paid off. I heard that even this creditable record was later broken.

The accumulated effects of the German effort against the Ludendorff Bridge finally began to weaken it seriously. After the fifth day, by which time our Treadways were fully capable of sustaining the troops on the far side, we ceased using the Ludendorff structure. American engineers, however, stubbornly and persistently continued the effort to strengthen the weakened members of the bridge so that it would be of future use. In this they failed. On March 17 the center span—the one which had been damaged by the unsuccessful German attempt to blow the bridge on March 7—fell into the river. It carried with it a number of our fine engineers, some of whom we were unable to rescue from the icy waters of the river.24

The diversion of five divisions to seize the Remagen bridgehead in early March did not modify or interfere with the development of the plan for destroying the German armies north of the Moselle. All during February the Third Army was engaged in necessary preparation for its attack toward the Rhine. Middleton’s VIII Corps advanced east beyond Prüm and Major General Manton S. Eddy’s XII Corps captured Bitburg. The XX Corps, under General Walker, eliminated resistance in the Saar–Moselle triangle by February 23, and a bridgehead was established over the Saar. The Siegfried defenses were penetrated and Trier was captured March 2. Two days later the XII Corps secured bridgeheads over the Kyll River.25

This was the signal for the main advance of the Third Army to begin. The VIII Corps attacked toward the northeastward and, breaking through all German resistance, reached Andernach on the Rhine on March 9, where it soon joined up with the First Army. The XII Corps launched a simultaneous attack northeastward along the northern bank of the Moselle and reached the Rhine March 10. Both these corps made great captures of enemy supplies and equipment and, as their spearheads joined up along the Rhine, they surrounded entire combat units of the enemy.26

The stunning victories by the First and Third Armies completed the second step in the planned destruction of the German forces west of the Rhine. There now remained only the great hostile garrison in the Saar Basin. These troops were situated in a huge triangle that had its base along the Rhine, with the two sides meeting in a point seventy-five miles to the west. The northern leg of this triangle was protected by the Moselle River and the southern by some of the strongest sections of the Siegfried Line. In retrospect it is difficult to understand why the German, as he saw his armies north of the Moselle undergo complete collapse and destruction, failed to initiate a rapid withdrawal of his forces in the Saar Basin, in order to remove them from their exposed position and employ them for defense of the Rhine.

More than once in prior campaigns we had witnessed similar examples of what appeared to us sheer tactical stupidity. I personally believed that the cause was to be found in the conqueror complex: the fear that to give up a single foot of ravished territory would be to expose the rotten foundation on which was built the myth of invincibility. Some of my staff thought that in the Saar the Germans were influenced to stand where they were by their faith in the defensive strength of the Moselle and the Siegfried Line. In addition the enemy was probably ignorant of the strength of the Seventh Army lying to the south of the Saar salient.

Such reasons as these would imply a woeful stupidity on the part of the German commanders and staffs. When free to act, they had proved their capacity too often for me to believe that the failure to pull back their exposed troops was a military decision—it was more of Hitler’s intuition in action!

During the first two acts of the month-long drama before the Rhine, I required Devers’ army group, except for the reduction of the Colmar pocket, to remain essentially on the defensive. In the meantime we had built up his American Seventh Army, under General Patch, to the unusual strength of fourteen divisions, not including one French division, the 3d Algerian. The stage was set for the third act.

Bradley was poised to strike at the nose of the triangular salient and at its northern base; Devers was ready to crush in its southern side.

The plan called for the American Seventh Army to launch a powerful assault in the direction of Worms. It was to penetrate the Siegfried Line and seize a bridgehead over the Rhine. Bradley was to launch an attack across the lower reaches of the Moselle so as to thrust deep into the rear of the forces facing the Seventh Army. Thus we expected by converging attacks to cut off the German forces and prevent their retreat across the Rhine. At the same time that these two attacks were launched at the base of the salient the nose would be struck by the right flank of the Third Army.27

The attack began March 15. The southern and western attacks met stiff opposition in the enemy’s strong defenses but made good progress, so much so that the entire German attention seemed centered on these two great attacks. This made the assault of the XII Corps, across the lower Moselle, very effective. The corps began crossing the river March 14 and during the entire operation never met heavy and organized resistance. This may have been because the Germans expected the corps to push northward down the Rhine, to join the forces east of the river in the Remagen bridgehead. In any event the Germans were completely surprised when the XII Corps leaped straight southward in one of the war’s most dramatic advances, to strike deeply into the heart of the Saar defenses.28

The enemy position quickly became hopeless. All around the perimeter of the salient the Americans battered their way forward while Eddy’s XII Corps effectively blocked almost every possible avenue of escape. Patton did not even pause when his forces reached the Rhine, but threw Major General Stafford Irwin’s 5th Division across the river without formal preparation of any kind. Irwin’s losses were negligible and on March 23 his division was well established in this second Allied bridgehead.29

Mopping up in the Saar was speedily accomplished and by March 25 all organized resistance west of the Rhine had ended.

All these operations were carried out in the now familiar pattern of air-ground partnership. Our powerful air force ranged far and wide and attacked important targets en masse, almost paralyzing the German power to maneuver and destroying quantities of vital supplies and equipment. While the weather was not ideal for air operations, it was never sufficiently bad to ground the air force completely.

On Washington’s Birthday the Allied air forces had staged an operation on such a vast scale as to be almost unique, even in an area where battle-front sorties had sometimes run as high as well over 10,000 in a single day. The operation was called Clarion and its purpose was to deliver one gigantic blow against the transportation system of Germany, with specific targets specially selected so as to occasion the greatest possible damage and the maximum amount of delay in their repair. Nine thousand aircraft, coming from bases in England, France, Italy, Belgium, and Holland, took part in the attack, and the targets were located in almost every critical area of Germany. Reaction was weak; the Luftwaffe was apparently unable to present an effective defense because of the widespread nature of the blow. It was a most imaginative and successful operation and stood as one of the highlights in the long air campaign to destroy the German warmaking power.

One of the notable features of the late winter campaign was the extraordinary conformity of developments to plans. Normally, in a great operation involving such numbers of troops over such vast fronts, enemy reaction and unforeseen developments compel continuous adjustment of plan. This one was an exception. The precision was due primarily to the great Allied air and ground strength; secondly to the fighting qualities of the troops and the skill of their platoon, battalion, and divisional leaders; and thirdly to the growing discouragement, bewilderment, and confusion among the defenders. Part of the price of the Battle of the Bulge was paid off by Hitler in the crushing defeats he suffered in February and March 1945.

All troops went into battle with orders to seize a bridgehead over the Rhine whenever the slightest opportunity presented itself, and all were alerted to the remote possibility of seizing a standing bridge. Our good fortune at Remagen hastened the end of Germany but had no real effect upon the battles then raging west of the river.

One slight change in plans occurred during the Saar battle. The boundary between Bradley’s and Devers’ army groups ran directly through the battlefield. This was deliberately arranged so as to obtain the full converging power of the Seventh and Third Armies on that stronghold. As the battle developed it became possible for Patton’s Third Army to move against objectives in Patch’s Seventh Army zone that Devers found it impossible to engage. Happening to be on the spot at the moment, I authorized appropriate boundary adjustments, specifying particularly close interarmy liaison. This involved also the transfer of an armored division from the Seventh to the Third Army.30 The insignificance of this slight change illustrates the accuracy with which staffs had calculated the probabilities.

During the month-long campaign our captures of German prisoners averaged 10,000 per day. This meant that the equivalent of twenty full divisions had been subtracted from the German Army, entirely aside from normal casualties in killed and wounded. The enemy suffered great losses in equipment and supplies, and in important areas of manufacture and sources of raw materials.31

We had by this time a logistic and administrative organization capable of handling such numbers of prisoners and these captives interfered only temporarily with troop maneuvers and offensives. We had come a long way from the time in Tunisia when the sudden capture of 275,000 Axis prisoners caused me rather ruefully to remark to my operations officers, Rooks and Nevins: “Why didn’t some staff college ever tell us what to do with a quarter of a million prisoners so located at the end of a rickety railroad that it’s impossible to move them and where guarding and feeding them are so difficult?”

By March 24 there was in the Remagen bridgehead an American army of three full corps, poised, ready to strike in any direction. Farther to the south the Third Army had made good a crossing of the Rhine and there was now in that region no hostile strength to prevent our establishing further bridgeheads almost at will.

Just to the north of the Remagen bridgehead ran the Sieg River, which flanked the Ruhr region on the south. So vital was the safety of the Ruhr to the German warmaking capacity that the enemy hastily assembled along the Sieg all of the remaining forces that he could spare from other threatened areas in the west, because the German assumed that we would strike directly against the Ruhr from Remagen.32

In this situation Hitler resorted to his old practice of changing senior commanders: Von Rundstedt was relieved from command, destined to take no further part in the war. Von Rundstedt, whom we always considered the ablest of the German generals, had been in command in the west when the landings were made June 6. Unable to drive the Allies back into the ocean, as ordered by Hitler, he had been relieved within three weeks after the landing and replaced by Von Kluge. When the latter fared no better than his predecessor Hitler again determined to make a change and called Von Rundstedt back into action. We understood at the time that the immediate cause of this second transfer was a belief that Von Kluge had participated in the July 20 plot against Hitler’s life.

Hitler now determined to bring Field Marshal von Kesselring up from Italy.