THE INDUSTRIAL IMPORTANCE OF THE RUHR TO Germany had been greatly diminished even before we surrounded it. Not only had the factories of the region been the targets of many heavy bombing raids but in February 1945 the Allied air force had initiated an interdiction program designed to cut the communication lines leading from the Ruhr into the heart of Germany. That operation had been markedly successful and we knew that the Germans were having great difficulty in transporting munitions from the Ruhr to the armies still remaining in the fields. As a consequence of the threats now developing on both sides of that area and because of its greatly diminished usefulness, it would have seemed logical for the Germans to withdraw their military forces for use in opposing our forward advances. Certainly it should have been clear to the German General Staff that when once the Ruhr was surrounded there would be lost not only its industries but whatever military forces might be jammed into its defenses. Nevertheless, the Germans once again stood in place.

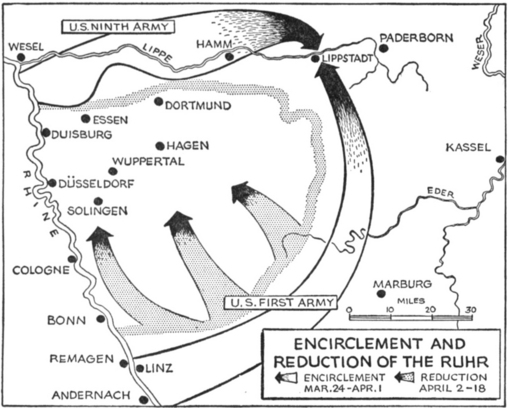

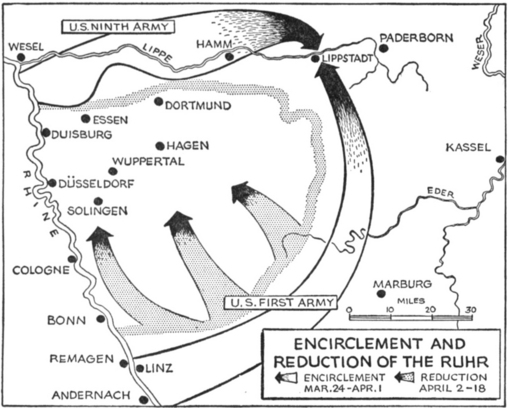

Bradley’s forces on the south and Montgomery’s in the north fought steadily toward their appointed meeting place near Kassel. The resistance to Simpson’s Ninth Army, which was on the right of Montgomery’s army group, was more stubborn than that encountered by the First and Third Armies advancing out of the Frankfurt area. As a result, the southern arm of our pincers swung well around the eastern and northeastern flanks of the Ruhr to meet Simpson’s advancing columns in the vicinity of Lippstadt, near Paderborn.

By April 1, just one week after the Twenty-first Army Group had crossed the Rhine in the Wesel sector, the junction was complete, the Ruhr was surrounded, and its garrison was trapped.

The Germans had now suffered an unbroken series of major defeats. Beginning with the bloody repulse in the enemy’s abortive Ardennes assault, the Allied avalanche had continued to inflict upon him a series of losses and defeats of staggering proportions. There was no atom of reason or logic in prolonging the struggle. In both the east and the west strong forces were now operating in the homeland of Germany. The Ruhr, the Saar, and Silesia were all lost to the enemy. His remaining industries, dispersed over the central area of the country, could not possibly support his armies still attempting to fight. Communications were badly broken and no Nazi senior commander could ever be sure that his orders would reach the troops for whom they were intended. While in many areas there were troops capable of putting up fierce and stubborn local resistance, only on the northern and southern flanks of the great western front were there armies of sufficient size to do more than delay Allied advances.

On March 31, I issued a proclamation to the German troops and people, urging the former to surrender and the latter to begin planting crops. I described the hopelessness of their situation and told them that further resistance would only add to their future miseries.

My purpose was to bring the whole bloody business to an end. But the hold of Hitler on his associates was still so strong and was so effectively applied elsewhere, through the medium of the Gestapo and SS, that the nation continued to fight.

When Bradley reached the Kassel region his problem was a double-headed one. He first had to compress the Ruhr defenders into a small enough pocket so that they could be contained with a few divisions and effectively prevented from interfering with his own communications. His second job was to organize his three armies for a main advance across the central plateau of Germany in the direction of Leipzig.

His three front-line armies were, from north to south, Simpson’s Ninth, Hodges’ First, and Patton’s Third. He had a total of forty-eight divisions, the largest exclusively American force in our history.1

Field Marshal Model commanded the German forces in the Ruhr pocket. He first attempted to break out of the encirclement by an attack toward the north, and he was defeated. A similar attempt toward the south was equally abortive, and the German garrison had nothing to look forward to except eventual surrender. Bradley kept hammering back the enemy lines and on April 14 the Americans launched a local attack that split the pocket in two. Two days later the eastern half collapsed. On the eighteenth the whole remaining garrison surrendered. Originally we had estimated we would capture about 150,000 of the German Army in the Ruhr. In the final count the total reached 325,000, including 30 general officers. We destroyed twenty-one divisions and captured enormous quantities of supplies. Hitler must have hoped that the siege of the Ruhr would be as stubbornly contested as was that of Brest, but within eighteen days of the moment the Ruhr was surrounded it had surrendered with an even greater number of prisoners than we had bagged in the final Tunisian collapse almost two years earlier.2

In the meantime Bradley had rapidly organized his forces for the eastward drive. By the time the Ruhr garrison surrendered, some of his spearheads had already reached the Elbe, a hundred and fifty miles from Kassel.3 Bradley’s advance was conducted on a broad front. On the south the Third Army struck in the direction of the Czechoslovakian border and toward the city of Chemnitz just north of that country. It reached that area April 13–14.4 On Patton’s left the First Army attack began April 11 and made rapid progress against scattered resistance. On the fourteenth the 3d Armored Division of Collins’ VII Corps reached Dessau, practically on the Elbe.5 This corps, which had been in the original assault against the Normandy beaches and soon thereafter had captured Cherbourg, had fought all the way across northwest Europe from the coast of France to the river Elbe.

April 12 I spent with George Patton. Before the day ended, the scenes I saw and news I heard etched the date in my memory. In the morning we visited some of Patton’s scattered corps and divisions, which were pushing rapidly eastward in a typical Patton thrust, here and there surrounding and capturing isolated detachments of the disintegrating enemy. There was no general line of resistance, or indeed even any co-ordinated attempt at delay. However, some of the local enemy detachments stubbornly defended themselves and we saw sporadic fighting throughout the day.

General Patton’s army had overrun and discovered Nazi treasure, hidden away in the lower levels of a deep salt mine.6 A group of us descended the shaft, almost a half mile under the surface of the earth.

At the bottom were huge piles of German paper currency, apparently heaped up there in a last frantic effort to evacuate some of it before the arrival of the Americans. In one of the tunnels was an enormous number of paintings and other pieces of art. Some of these were wrapped in paper and burlap, others were merely stacked together like cordwood.

In another tunnel we saw a hoard of gold, tentatively estimated by our experts to be worth about $250,000,000, most of it in gold bars. These were in sacks, two 25-pound bars to each sack. There was also a great amount of minted gold from the different countries of Europe and even a few millions of gold coins from the United States.

Crammed into suitcases and trunks and other containers was a great amount of gold and silver plate and ornament obviously looted from private dwellings throughout Europe. All the articles had been flattened by hammer blows, obviously to save storage space, and then merely thrown into the receptacle, apparently pending an opportunity to melt them down into gold or silver bars.

Attention had been originally drawn to the particular tunnel in which all this gold was stored by the existence of a newly built brick wall in the center of which was a steel safe door of the most modern type. The safe door was so formidable that heavy explosive charges would certainly have been necessary for its demolition. However, to an American soldier who inspected it the surrounding brick wall did not look particularly strong, and he tested out his theory with a mere half stick of TNT. With this he blew an enormous hole completely through the obstruction and the hoard was exposed to view. We speculated as to why the Germans had not attempted to provide a concealed hiding place for the treasure in the labyrinth of tunnels instead of choosing to attempt its protection by a wall that could easily have been demolished by a pickax. The elaborate steel door made no sense to us at all, but an American soldier who accompanied me remarked, “It’s just like the Germans to lock the stable door but to tear out all its sides.” Patton’s story of the incident that led to the exploration of the mine was in itself intriguing.

It is probable, of course, that sooner or later the mine would have been carefully searched by the captors. But according to Patton, except for the instincts of human decency on the part of two Americans, we might not have discovered it until much of it had been more securely hidden away. The story was this:

In the little neighboring town the advancing Americans had established a curfew law. Any civilian in the streets after dark was instantly picked up for questioning. One evening a roving patrol in a jeep saw a German woman hurrying along the street after curfew and stopped to speak to her. She protested that she was rushing off to get a midwife for her neighbor, who was about to have a child. The American soldiers decided to check on the story, being quite ready to help if it should prove to be correct. They took the German woman into their jeep, picked up the midwife, and returned to the accouchement, which was all as described by the German woman. The soldiers, still helpful, remained long enough to return the German woman and her midwife friend to their homes. As they were going along the street they passed the mouth of one of the salt mines of that region and one of the women remarked, “That’s the mine in which the gold is buried.”

This remark excited the curiosity of the soldiers and they questioned the women sufficiently to learn that some weeks earlier great loads of material had been brought from the east to be put into the mine. The soldiers reported the story to their superiors, who in turn sought out some of the German officials of the mining corporation and the whole treasure fell into our hands.

The same day I saw my first horror camp. It was near the town of Gotha. I have never felt able to describe my emotional reactions when I first came face to face with indisputable evidence of Nazi brutality and ruthless disregard of every shred of decency. Up to that time I had known about it only generally or through secondary sources. I am certain, however, that I have never at any other time experienced an equal sense of shock.

I visited every nook and cranny of the camp because I felt it my duty to be in a position from then on to testify at first hand about these things in case there ever grew up at home the belief or assumption that “the stories of Nazi brutality were just propaganda.” Some members of the visiting party were unable to go through the ordeal. I not only did so but as soon as I returned to Patton’s headquarters that evening I sent communications to both Washington and London, urging the two governments to send instantly to Germany a random group of newspaper editors and representative groups from the national legislatures. I felt that the evidence should be immediately placed before the American and British publics in a fashion that would leave no room for cynical doubt.7

The day of April 12 ended on a note of dramatic climax. Bradley, Patton, and I sat up late talking of future plans, particularly of the selection of officers and units for early redeployment to the Pacific. We went to bed just before twelve o’clock, Bradley and I in a small house at Patton’s headquarters, and he in his trailer. His watch had stopped, and he turned on the radio to get the time signals from the British Broadcasting Corporation. While doing so he heard the news of President Roosevelt’s death. He stepped back into the house, woke up Bradley, and then the two of them came to my room to tell me the shocking news.

We pondered over the effect the President’s death might have upon the future peace. We were certain that there would be no interference with the tempo of the war because we already knew something of the great measures afoot in the Pacific to accomplish the smashing of the Japanese. We were of course ignorant of any special or specific arrangements that President Roosevelt had made affecting the later peace. But we were doubtful that there was any other individual in America as experienced as he in the business of dealing with the other Allied political leaders. None of us had known the President very well; I had, through various conferences, seen more of him than the others, but it seemed to us, from the international viewpoint, to be a most critical time to be forced to change national leaders. We went to bed depressed and sad.

With some of Mr. Roosevelt’s political acts I could never possibly agree. But I knew him solely in his capacity as leader of a nation at war—and in that capacity he seemed to me to fulfill all that could possibly be expected of him.

During the First Army’s advance more, than 15,000 of the enemy were cut off in the Harz Mountains. The defenders fought stubbornly and held out until April 21. The country was exceedingly difficult. The week-long fighting to reduce the pocket and to beat off other German troops who attempted to relieve the garrison was of a bitter character.8 Still farther to the north Simpson’s Ninth Army kept equal pace with the advance in the center and the south. By April 6 the Ninth had established a bridgehead over the formidable Weser River and thereafter dashed for the Elbe, which it reached just south of Magdeburg April 11. The next day the 2d Armored Division of the Ninth Army achieved a small bridgehead over the Elbe, ten miles below. Establishment of another small bridgehead by the 5th Armored Division of the XIII Corps north of Magdeburg was thwarted when the enemy blew the bridge. In this sector the enemy appeared to be willing to abandon the country west of the Elbe but savagely opposed any attempt to cross the river. The Germans immediately counterattacked the bridgehead of the 2d Armored Division, which was abandoned April 14. A crossing farther south by the 83d Division was maintained.9

Almost coincidentally with our arrival on the Elbe the Red Army launched a powerful westward drive from its positions on the Oder. The attack was on a front of more than two hundred miles. The Red drive made speedy progress everywhere. Its northern flank pushed in the direction of the Danish peninsula, the center toward Berlin, and the southern flank toward the Dresden area. On April 25 patrols of the 69th Division of the V Corps met elements of the Red Army’s 58th Guards Division on the Elbe. The meeting took place at Torgau, some seventy-five miles south of Berlin. The V Corps, like the VII, had participated in the initial assault on the beaches of Normandy and it seemed eminently fitting that troops of one of these corps should be first to make contact with the Red Army and accomplish the final severance of the German nation.10 The problem of liaison with the Russians grew constantly more important as we advanced across central Germany. The pressing questions were no longer those of major strategy but had become tactical in character. One of the principal difficulties was that of mutual identification.

Because of differences in language front-line radios were useless as a means of communication between the two converging forces. The only solution to the problem seemed to lie in timely agreements upon markings and procedures. As early as the beginning of April the air forces of the Western Allies and the Russians had come into contact, with some unfortunate results. Shots had been exchanged between Red aircraft and our own, and the danger of major clashes continued to increase. The task of organizing a system of recognition signals was laborious and was not fully accomplished until April 20. However, both sides had already agreed upon restraining lines for the use of their air forces, and by the exercise of care, accompanied by a considerable degree of good fortune, no really serious errors took place.11

It was also agreed between ourselves and the Russians that when troops of the two converging forces met local commanders would arrange satisfactory junction lines between the two, based upon local and operational considerations. For the general junction line between the two forces we were anxious to have an easily identified geographical feature. For this reason the agreed-upon line, in the center of the front, followed the Elbe and Mulde rivers. It was understood that the withdrawal of our forces to their occupation zone would take place at whatever future date might be agreed upon by our respective governments.

While this decisive advance was taking place in the center the Twenty-first Army Group on the north and the Sixth on the south were both carrying out the operations assigned to them.

In the north Montgomery’s Twenty-first Army Group advanced toward Bremen and Hamburg and pushed a column forward to the Elbe to protect the northern flank of Bradley’s advance. Montgomery’s eastward advance was carried out mainly by the British Second Army, while the Canadian Army thrust northward through Arnhem to clear northeast Holland and the coastal belt eastward toward the Elbe. The eastward advance of the British Second Army, with three corps in the front line, reached the Weser April 6 and the Elbe April 19. At Bremen the British Army encountered an enemy force determined to resist to the bitter end. The British 30 Corps reached the outskirts of the city April 20, but a week of bitter fighting was necessary before Bremen finally surrendered.12

Likewise, the northward advance of the Canadian Army on Montgomery’s left initially encountered some desperate resistance. However, satisfactory advances were made all along the line and Arnhem was captured April 15. The fall of Arnhem was the signal for the enemy in that sector to withdraw into the Holland fortress behind flooded areas which posed a serious obstacle to an advance into western Holland.

Montgomery believed, and I agreed, that an immediate campaign into Holland would result in great additional suffering for that unhappy country whose people were already badly suffering from lack of food. Much of the country had been laid waste by deliberate flooding of the ground, by bombing, and by the erection of German defenses. We decided to postpone operations into Holland and to do what we could to alleviate suffering and starvation among the Dutch people.13

The mission of Devers’ Sixth Army Group during the early days of April was to protect the right flank of Bradley’s advance. To carry out this mission Devers organized a methodical advance by Patch’s Seventh Army on his left and the French First Army on his right.14

Initially the opposition on the front of the Sixth Army Group was general and, despite the debacle in the north and the daily losses of battle, the Germans continued stubbornly to resist. When the Seventh Army reached the Neckar River it had to fight hard to establish a crossing and then required a week to reduce the garrison in the town of Heilbronn. The German troops in this region were not so seriously demoralized by the great Allied advances of February and March as were those who had borne the brunt of our attacks. On April 7 the 10th Armored Division made a thrust in the direction of Crailsheim but German reaction was so speedy and strong that the division had to withdraw hastily from its exposed position. The XV Corps reached Nürnberg April 16 but again several days of fighting were necessary before the defenses of the city finally collapsed.15

Resistance in the French sector was not so strong. After some sharp fighting in the immediate vicinity of the Rhine the French advance became rapid.

The French Army, of course, went into the attack under the orders of General Devers, who was responsible for the allocation of army boundaries, routes of supply, and all the other administrative arrangements necessary for troop maintenance throughout his army group. These boundaries placed the city of Stuttgart in Patch’s Seventh Army zone, because the supply routes of the Americans would necessarily run through that place. The city was captured by the French, who afterward refused to evacuate to permit its use by Patch. So unyielding were the French in their assertion that national prestige was involved that the argument was referred to me. I instructed Devers to stand firm and to require compliance with his plan. The French still proved obstinate and referred the matter to Paris. Not content with this, General de Gaulle continued to maintain an unyielding attitude on the governmental level in his reply to a sharply worded message from the President of the United States on the subject. In the meantime I had warned the French commander that under the circumstances it was necessary for me to inform the Combined Chiefs of Staff that I could no longer count with certainty on the operational use of any French forces they might be contemplating equipping in the future. This threat of a possible curtailment of equipment for the French forces proved effective, and the French finally complied.16

A somewhat similar instance occurred on the French-Italian border, where there was a tiny bit of territory to which the French and Italians had each asserted moral and legal rights of possession. In that region I had made a boundary arrangement with Field Marshal Alexander, and this agreement was violated by the French in their anxiety to strengthen their claims to the disputed piece of territory.17

The French position in the war was, of course, not an easy one. Once known as the foremost military power of Europe, their Army as well as their pride had been shattered in the great debacle of 1940. Consequently when the Torch invasion of 1942 again gave patriotic Frenchmen an opportunity to join in the fight against the Nazis they were sensitive to all questions of national pride and honor. Added to this was their bitter hatred of the Nazi, a hatred which seemed to be intensified against some of their own former political and military leaders. On top of all this was the uncertain basis on which rested De Gaulle’s authority and that of the governmental organization he had installed in France. A further factor was the complete dependence of the French Army, and indeed of considerable portions of the population, upon American supplies. This was an additional irritant to their pride and, although they constantly insisted upon the need for greater amounts of every kind of equipment and matériel, they were naturally galled by the realization that without those supplies they were completely helpless. All this tended to make them peculiarly sensitive and therefore difficult to deal with when they could find in any question, no matter how trivial, anything that they thought involved their national honor. Nevertheless, America’s investment in the French forces paid magnificent dividends.

In the African campaign the French were helpful but extremely weak. So far as heavy fighting was concerned they first took a significant part in the war in Italy. In late 1943 and early 1944 the French corps in that theater did excellent work. Moreover, they performed brilliantly in the invasion of southern France, in the penetration of the Vosges Mountains, and the advance to the upper Rhine. Their efficiency rapidly fell off with the arrival of winter weather in late 1944 because of the large proportion of African native troops in their Army, who were unable to endure the cold and exposure incident to campaigning in a European winter. In the spring of 1945, however, during the final operations of the war, the French Army advanced gallantly and effectively to occupy great portions of southern Germany. At the same time they conducted a ground and air campaign against the Germans on the Bay of Biscay that resulted in the liberation of Bordeaux and the island of Oléron. This operation had been repeatedly postponed since the autumn of 1944 because of more urgent demands elsewhere. The battle commenced on April 14; a week later the Gironde had been cleared to the sea; by May 1, Oléron had fallen. When inspired, the French are great fighters.

Among the French were numbers of important individuals who never caused the slightest trouble; men whose breadth of vision and understanding of the issues at stake made them splendid allies. I personally liked General de Gaulle, as I recognized in him many fine qualities. We felt, however, that these qualities were marred by hyper-sensitiveness and an extraordinary stubbornness in matters which appeared inconsequential to us. My own wartime contacts with him never developed the heat that seemed to be generated frequently in his meetings with many others.

Giraud was my friend. He was a fighting man and thoroughly honest and straightforward. His complete lack of interest in political matters, however, obviously disqualified him for any political post in his country’s service. Generals Juin, Koenig, Koeltz, and innumerable junior officers were courageous, honest, and capable professionals. The names of Generals Mast and Bethouart and their associates who first risked their lives in order to bring about restoration of France through Allied intervention in Africa will always live as symbols of the highest kind of patriotism and greatness of character.

With Bradley’s army group firmly established on the Elbe, the stage was now set for the final Allied moves of the campaign. The enemy was split into independent commands in the north and south and had no means of restoring a single front against either the Russians or ourselves. With his world collapsing about him, the German soldier lost all desire to fight. Only in isolated instances did commanders succeed in maintaining cohesion among their units. During the first three weeks of April the Western Allies captured more than a million prisoners.18

Even before the Allied advance across central Germany began, we knew that the German Government was preparing to evacuate Berlin. The administrative offices seemed to be moving to the southward, possibly, we thought, to Berchtesgaden in the National Redoubt. Continuation of the movement was no longer possible after Bradley’s speedy advance barred further north-south traffic across the country. We knew also that Hitler had been unable to go south and that he was making his last stand in Berlin. Nevertheless, the strong possibility still existed that fanatical Nazis would attempt to establish themselves in the National Redoubt, and the early overrunning of that area remained important to us.19 In the north also there remained weighty reasons for speeding up the planned attack in the direction of Lübeck.

The Lübeck advance would capture the last remaining submarine bases of the German and would effectively eliminate the final vestiges of that once serious menace.

We could not predict the action of the German occupation forces in Denmark. It was possible they would choose to defend that region stubbornly and in that event we planned to conduct a lightning campaign against them.

In early April, Montgomery had estimated that, to carry out the mission assigned him, he would need no strength beyond the seventeen divisions then in his Twenty-first Army Group. I offered him additional logistic assistance by reserving for him a portion of the capacity of the American railroad bridge at Wesel. This help he declined.20 But as the operations developed on his flank, he found his troops rapidly used up and in the interests of speed asked for additional strength and supply assistance. Both I was glad to provide. I attached temporarily to Montgomery’s force the U. S. XVIII Airborne Corps under General Ridgway. It was to operate in a ground role to support Montgomery’s attack. But we were also prepared, in the event the Germans in Denmark should decide to fight to a finish, to provide additional strength for an airborne attack to cross the Kiel Canal.

When Bremen finally fell to Montgomery’s force April 26, the resistance in his front became markedly weaker. He quickly transferred his main effort to the sector of the British 8 Corps, which launched an attack across the Elbe April 29. The U. S. XVIII Corps made a simultaneous crossing somewhat to the south and provided right-flank protection to the British Second Army in its further advances.

On May 1 the 11th Armored Division of the British 8 Corps began a brilliant dash across Schleswig-Holstein to the Baltic and entered Lübeck on the afternoon of May 2. This sealed off the enemy in Denmark and also prevented any of the defeated forces in Germany from withdrawing into that country.

Montgomery now rapidly consolidated his gains all along his front and on May 3 the U. S. XVIII Corps made contact with the Russians in Montgomery’s sector. With Berlin in flames and the northern flank of the Red Army attack sweeping in our direction across Germany, all resistance collapsed. Swarms of Germans streaming back from the Russian front now began giving themselves up to the Anglo-American armies. American troops standing on the Elbe daily received these prisoners by the thousands.

On Montgomery’s left his Canadian Army had, in the meantime, continued its successful operations and rapidly cleaned up its entire front except that it made no attempt to turn back into western Holland, where the German Twenty-fifth Army was entrenched.

We knew that conditions in Holland had been steadily deteriorating and, after the advance of our armies had isolated the area from Germany, the Dutch situation became almost intolerable. Judging from the information available to me, I feared that wholesale starvation would take place and decided to take positive steps to prevent it. I still refused to consider a major offensive into the country. Not only would great additional destruction and suffering have resulted but the enemy’s opening of dikes would further have flooded the country and destroyed much of its fertility for years to come. I warned General Blaskowitz, the German commander in Holland, to refrain from opening any more dikes and pointed out to him that nothing he could do in Holland would impede the speedy collapse of Germany.21

The Nazi High Commissioner in Holland, Seyss-Inquart, offered a local solution by proposing a truce. If the Allied forces would refrain from any westward advance into Holland no further flooding would take place in the country and the Germans would co-operate in the introduction of relief supplies. My military superiors had already given me a free hand in the matter and I accordingly sent my chief of staff, General Smith, to meet Seyss-Inquart on April 30. They agreed upon methods of introducing food and supplies, which the Allies had already accumulated for the purpose. Large-scale deliveries began immediately. Even before this we had been sending small amounts of food into the country by free parachute. General Smith carried to Seyss-Inquart a warning that I would tolerate no interference with the relief program and that if the Germans were guilty of any breach of faith I would later refuse to treat them as prisoners of war. I considered that continued occupation of Holland by the Germans was senseless and that any further repressive acts for which they were responsible should be punished. At the conference General Smith also proposed that the German commander Blaskowitz should surrender his forces at once. Seyss-Inquart reported, however, that as long as the German Government held out Blaskowitz could under no circumstances capitulate.22

Simultaneously with all these operations on the north equally decisive movements were progressing in the south. The principal line of advance was southeast down the Danube Valley toward Linz, with the purpose of joining up with the Russians in Austria. Since Bradley’s offensive in the center had already gained its objectives we had the Third Army available to conduct this drive while the Sixth Army Group gave its entire attention to overrunning the Redoubt area farther to the south and west. In order to make certain of Devers’ rapid advance we assigned to him the U. S. 13th Airborne Division, to use whenever he deemed advisable. So rapid, however, were the ground advances that the 13th Airborne Division was not needed and, as it turned out, this was the only American division to enter Europe that never engaged in active battle.23

The advance of the Third Army down the Danube began April 22. The enemy made an attempt at defense at Regensburg but both the III and XX Corps quickly established bridgeheads across the Danube east and west of the city and advanced rapidly down the river. The XII Corps’s 11th Armored Division plunged ahead on May 5 to receive the surrender of the German garrison at Linz in Austria.24

With his main forces pushing down the Danube, Patton’s Third Army was now reinforced by the V Corps from Hodges’ army. Patton directed the V to push eastward into Czechoslovakia. The corps captured Pilsen May 6. In this area the Russian forces were rapidly advancing from the east and careful co-ordination was again necessary. By agreement we directed the American troops to occupy the line Pilsen–Karlsbad, while south of Czechoslovakia the agreed line of junction ran down the Budějovice–Linz railroad and from there along the valley of the Enns River.25

The final major move of Patch’s Seventh Army in Devers’ army group began April 22. On the right flank the XV Corps moved down the Danube and turned southward to strike at Munich, the place of origin of the Nazi movement. That great city was captured April 30. On May 4 the 3d Division of the same corps captured Berchtesgaden. Other troops occupied Salzburg. The defenses of the entire sector disintegrated.26

The XXI and VI Corps of the Seventh Army crossed the Danube April 22 and advanced steadily toward the National Redoubt. On May 3, Innsbruck was taken and the 103d Division of the VI Corps pushed on into the Brenner Pass. There, on the Italian side of the international boundary, this American division of the Allied command met the American 88th Division of the U. S. Fifth Army, advancing from Italy. My prediction of a year and a half before that I would meet the soldiers of the Mediterranean command “in the heart of the enemy homeland” was fulfilled.

Throughout the front principal objectives in all sectors were attained by the end of April or their early capture was a certainty. The great advances had the effect of multiplying many of the administrative, maintenance, and organizational problems with which we constantly had to wrestle. Again a tremendous strain was placed upon our supply lines. Distance alone would have been enough to stop our spearheads had we been dependent solely upon surface transport, efficient as it was. Distant and fast-moving columns were sometimes almost solely dependent upon air supply, and during April we kept 1500 transport planes constantly working in our supply system. They became known as “flying boxcars” and were never more essential than in these concluding stages of the war. Besides these planes we stripped and converted many heavy bombers to the same purpose. During the month of April the air forces delivered to the front lines 60,000 tons of freight, in which was included 10,000,000 gallons of gasoline.27

Our troops were everywhere swarming over western Germany and there were few remaining targets against which the air force could be directed without danger of dropping their bombs on either our own or the Russian troops. In the late days of the war, however, the air force carried out two important bombing raids. One was by British Bomber Command against the fortress island of Heligoland, which was attacked in order to help Montgomery in case he found it necessary to assault across the Kiel Canal.28 The other one was by the U. S. Eighth Air Force against Berchtesgaden. That stronghold and symbol of Nazi arrogance was thoroughly pounded with high explosives. The bombing took place when we still thought the Nazis might attempt to establish themselves in their National Redoubt with Berchtesgaden as the capital. The photo reconnaissance units brought back pictures that showed our bombers had reduced the place to a shambles; from them we derived a gleeful and understandable satisfaction.29

On each return trip from the front our transports and converted bombers brought back planeloads of recaptured Allied prisoners. These men were concentrated at convenient camps for rehabilitation and early transfer to the homelands. Near Le Havre, in one camp alone, called Lucky Strike, we had at one time 47,000 recovered American prisoners. The British had similar camps at various places in northwest France and Belgium. The recovery of so many prisoners in such a short space of time presented delicate problems to the Medical Corps, to the Transport Service, and indeed to all of us. In many instances the physical condition of the prisoners was so poor that great care had to be exercised in their feeding. The weaker ones were hospitalized and for a period our hospitals were crowded with men whose joy at returning to their own people was almost pathetic, but who at the same time were suffering so badly from malnutrition that only expert care could save them. Some of the Americans had been prisoners since the early battles in Tunisia in December 1942. On the British side we recovered men who had been captured at Dunkirk in 1940.

One day I had an appointment to meet five United States senators. As they walked into my office I received a telegram from a staff officer, stating that a newspaper article alleged the existence at the Lucky Strike camp of intolerable conditions. The story said that men were crowded together, were improperly fed, lived under unsanitary conditions, and were treated with an entire lack of sympathy and understanding. The policy was exactly the opposite. Automatic furloughs to the States had been approved for all liberated Americans and we had assigned specially selected officers to care for them.

Even if the report should prove partially true it represented a very definite failure to carry out strict orders somewhere along the line. I determined to go see for myself and told my pilot to get my plane ready for instant departure. I turned to the five senators, apologized for my inability to keep my appointment, and explained why it was necessary for me to depart instantly for Lucky Strike. I told them, however, that if they desired to talk with me they could accompany me on the trip. I pointed out that at Lucky Strike they would have a chance to visit with thousands of recovered prisoners of war and that at no other place could they find such a concentration of American citizens. They all accepted with alacrity.

In less than two hours we arrived at Lucky Strike and started our inspection. We roamed around the camp and found no basis for the startling statements made in the disturbing telegram. There were only two points concerning which our men exhibited any impatience. The first of these was the food. It was of good quality and well cooked but the doctors would not permit salt, pepper, or any other kind of seasoning to be used because they were considered damaging to men who had undergone virtual starvation over periods ranging from weeks to years. The senators and I had dinner with the men and we agreed that a completely unseasoned diet was lacking in taste appeal. However, it was a technical point on which I did not feel capable of challenging the doctors.

The other understandable complaint was the length of time that men were compelled to stay in the camp before securing transportation to America. This was owing to lack of ships. Freighters, which constituted the vast proportion of our overseas transport service at that stage of the war, were not suited for transportation of passengers. These ships lacked facilities for providing drinking water, while toilet and other sanitary provisions were normally adequate only for the crew. The men did not know these things and it angered them to see ships leaving the harbor virtually empty when they were so anxious to go home.

So pleased did the soldiers seem to be by our visit that they followed us around the camp by the hundreds. When we finally returned to the airplane we found that an enterprising group had installed a loud-speaker system, with the microphone at the door of my plane. A committee of sergeants came up and rather diffidently said that the men would like to see and hear the commanding general. There were some fifteen to twenty thousand in the crowd around the plane.

In hundreds of places under almost every kind of war condition I had talked to American soldiers, both individually and in groups up to the size of a division. But on that occasion I was momentarily at a loss for something to say. Every one of those present had undergone privation beyond the imagination of the normal human. It seemed futile to attempt, out of my own experience, to say anything that could possibly appeal to such an enormous accumulation of knowledge of suffering.

Then I had a happy thought. It was an idea for speeding up the return of these men to the homeland. So I took the microphone and told the assembled multitude there were two methods by which they could go home. The first of these was to load on every returning troopship the maximum number for which the ship was designed. This was current practice.

Then I suggested that, since submarines were no longer a menace, we could place on each of these returning ships double the normal capacity, but that this would require one man to sleep in the daytime so that another soldier could have his bunk during the night. It would also compel congestion and inconvenience everywhere on the ship. I asked the crowd which one of the two schemes they would prefer me to follow. The roar of approval for the double-loading plan left no doubt as to their desires.

When the noise had subsided I said to them: “Very well, that’s the way we shall do it. But I must warn you men that there are five United States senators accompanying me today. Consequently when you get home it is going to do you no good to write letters to the papers or to your senator complaining about overcrowding on returning ships. You have made your own choice and so now you will have to like it.”

The shout of laughter that went up left no doubt that the men were completely happy with their choice. I never afterward heard of a single complaint voiced by one of them because of discomfort on the homeward journey.

The war’s end was now in sight. The possible duration of hostilities could be measured in days; the only question was whether the finale would come by linking up throughout the gigantic front with the Red Army and the forces from Italy, or whether some attempt would be made by the German Government to capitulate.

Some weeks before the final surrender we received intimations that various individuals of prominence in Germany were seeking ways and means of accomplishing capitulation. In no instance did any of these roundabout messages involve Hitler himself. On the contrary, each sender was so fearful of Nazi wrath that he was as much concerned in keeping secret his own part in the matter as he was in achieving the surrender of the German armies.

One early hint of German defection was a feeler that came through the British Embassy in Stockholm. Its stated purpose was to arrange a truce in the west; this was an obvious attempt to call off the war with the Western Allies so that the German could throw his full strength against Russia. Our governments rejected the proposal.30

Another came out of Switzerland, under mysterious circumstances, from a man named Wolff. There was apparently afoot a plot to surrender to Alexander the German forces in Italy.31 Our own headquarters had nothing to do with this particular instance but we were kept informed because of the definite signs of weakening determination on the part of higher German officials. Receipt of any such tip or of a bona fide message always caused a terrific amount of work and involved much care because of the numbers of nations involved on the Allied side, each of which was naturally concerned that its own interests be fully protected. In the Wolff incident the Western Allies, although proceeding in good faith to determine the authenticity of the message and the authority of the man who initiated it, incurred the suspicion of the Soviets. A great deal of explanation was necessary and it put us definitely on notice to be careful if any such message should reach us.

The first direct suggestion of surrender that reached SHAEF came from Himmler, who approached Count Bernadotte of Sweden in an attempt to get in touch with Prime Minister Churchill.32 On April 26, I received a long message from the Prime Minister, discussing Himmler’s proposal to surrender the western front. I regarded the suggestion as a last desperate attempt to split the Allies and so informed Mr. Churchill. I strongly urged that no proposition be accepted or entertained unless it involved a surrender of all German forces on all fronts. My view was that any suggestion that the Allies would accept from the German Government a surrender of only their western forces would instantly create complete misunderstanding with the Russians and bring about a situation in which the Russians could justifiably accuse us of bad faith. If the Germans desired to surrender an army, that was a tactical and military matter. Likewise, if they wanted to surrender all the forces on a given front, the German commander in the field could do so, and the Allied commander could accept; but the only way the government of Germany could surrender was unconditionally to all the Allies.

This view coincided with the Prime Minister’s, and he and the President promptly provided full information to Generalissimo Stalin, together with a statement of their rejection of the proposal.

However, until the very last the Germans never abandoned the attempt to make a distinction between a surrender on the western front and one on the eastern. With the failure of this kind of negotiation German commanders finally had, each in his own sector, to face the prospect of complete annihilation or of military surrender.

The first great capitulation came in Italy. Alexander’s forces had waged a brilliant campaign throughout the year 1944 and by April 26, 1945, had placed the enemy in an impossible situation. Negotiations for local surrender began and on April 29 the German commander surrendered. All hostilities in Italy were to cease May 2.

This placed the German troops just to the north of Italy in an equally impossible situation. On May 2 the German commander requested the identity of the Allied commander he should approach in order to surrender and was told to apply to General Devers. He was warned that only unconditional surrender would be acceptable. This enemy force was known as Army Group G and comprised the German First and Nineteenth Armies. They gave up on May 5, with the capitulation to be effective May 6.33

Far to the north, in the Hamburg area, the German commander also saw the hopelessness of his situation. On April 30 a German emissary appeared in Stockholm to say that Field Marshal Busch, commanding in the north, and General Lindemann, commanding in Denmark, were ready to surrender as quickly as the Allied advance reached the Baltic. We were told that the Germans would refuse to surrender to the Russians but that, once the Western Allies had arrived at Lübeck and so cut off the forces in that region from the arrival of fanatical SS formations from central Germany, they would immediately surrender to us. Montgomery’s forces arrived in Lübeck May 3. By then, however, a great change in the governmental structure of Germany had taken place.

Hitler had committed suicide and the tattered mantle of his authority had fallen to Admiral Doenitz. The admiral directed that all his armies everywhere should surrender to the Western Allies. Thousands of dejected German soldiers began entering our lines. On May 3, Admiral Friedeburg, who was the new head of the German Navy, came to Montgomery’s headquarters. He was accompanied by a staff officer of Field Marshal Busch. They stated that their purpose was to surrender three of their armies which had been fighting the Russians and they asked authority to pass refugees through our lines. Their sole desire was to avoid surrender to the Russians. Montgomery promptly refused to discuss a surrender on these terms and sent the German emissaries back to Field Marshal Keitel, the chief of the German high command.

I had already told Montgomery to accept the military surrender of all forces in his allotted zone of operations. Such a capitulation would be a tactical affair and the responsibility of the commander on the spot. Consequently, when Admiral Friedeburg returned to Montgomery’s headquarters on May 4 with a proposal to surrender all German forces in northwest Germany, including those in Holland and Denmark, Montgomery instantly accepted. The necessary documents were signed that day and became effective the following morning.34 When Devers and Montgomery received these great surrenders they made no commitments of any kind that could embarrass or limit our governments in future decisions regarding Germany; they were purely military in character, nothing else.

On May 5 a representative of Doenitz arrived in my headquarters. We had received notice of his coming the day before. At the same time we were informed that the German Government had ordered all of its U-boats to return to port. I at once passed all this information to the Russian high command and asked them to designate a Red Army officer to come to my headquarters as the Russian representative in any negotiations that Doenitz might propose. I informed them that I would accept no surrender that did not involve simultaneous capitulation everywhere. The Russian high command designated Major General Ivan Suslaparov.35

Field Marshal von Kesselring, commanding the German forces on the western front, also sent me a message, asking permission to send a plenipotentiary to arrange terms of capitulation. Since Von Kesselring had authority only in the West, I replied that I would enter into no negotiations that did not involve all German forces everywhere.36

When Admiral Friedeburg arrived at Reims on May 5 he stated that he wished to clear up a number of points. On our side negotiations were conducted by my chief of staff, General Smith. The latter told Friedeburg there was no point in discussing anything, that our purpose was merely to accept an unconditional and total surrender. Friedeburg protested that he had no power to sign any such document. He was given permission to transmit a message to Doenitz, and received a reply that General Jodl was on his way to our headquarters to assist him in negotiations.

To us it seemed clear that the Germans were playing for time so that they could transfer behind our lines the largest possible number of German soldiers still in the field. I told General Smith to inform Jodl that unless they instantly ceased all pretense and delay I would close the entire Allied front and would, by force, prevent any more German refugees from entering our lines. I would brook no further delay in the matter.

Finally Jodl and Friedeburg drafted a cable to Doenitz requesting authority to make a complete surrender, to become effective forty-eight hours after signing. Had I agreed to this procedure the Germans could have found one excuse or another for postponing the signature and so securing additional delay. Through Smith, I informed them that the surrender would become effective forty-eight hours from midnight of that day; otherwise my threat to seal the western front would be carried out at once.

Doenitz at last saw the inevitability of compliance and the surrender instrument was signed by Jodl at two forty-one in the morning of May 7. All hostilities were to cease at midnight May 8.37

After the necessary papers had been signed by Field Marshal Jodl and General Smith, with the French and Russian representatives signing as witnesses, Field Marshal Jodl was brought to my office. I asked him through the interpreter if he thoroughly understood all provisions of the document he had signed.

He answered, “Ja.”

I said, “You will, officially and personally, be held responsible if the terms of this surrender are violated, including its provisions for German commanders to appear in Berlin at the moment set by the Russian high command to accomplish formal surrender to that government. That is all.”

He saluted and left.