10

—

The Permit

I MANAGE TO finish one of the two books that Book Uncle gave me. It is a mystery — the kind of book you can read in one big gulp and it does not feel like work. Not like that dove book. Skinny as that one was, its story is still flapping around in my mind.

The second Book Uncle book is a karate book. I’ll read it later and then maybe I’ll pass it on to Anil.

In the morning, before I catch the bus to school, I decide to return the mystery book. That way I can get a new one.

I’m thinking I’d like to give a book to Reeni, too, but she’s not interested in karate. Maybe Book Uncle can find me a book Reeni would like. Something about animals or movies. Reeni is crazy about animals, the bigger the better. She’s only a little less crazy about movies.

Oh, she is a crazy girl, my friend Reeni, and I want her back. I want her not to be angry with me anymore.

I’m busy tossing all these thoughts around in my mind, but then I get to the corner. The istri lady is yelling at her son. The buses are rattling down the road. It seems like a normal morning. But is it?

Because what I see stops me cold.

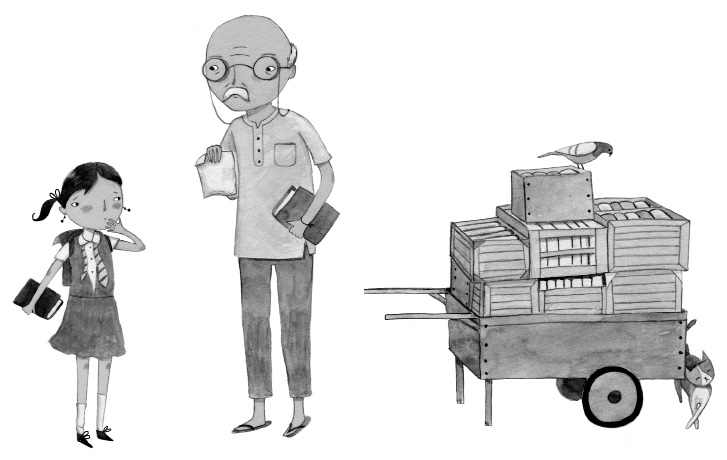

Book Uncle’s place looks different. Book Uncle looks different.

“Good morning, Yasmin-ma,” he says. He’s not smiling.

The books are still in their boxes. He hasn’t even set them out yet, the way he does each morning.

What’s wrong?

Book Uncle is just standing there with a pink paper in his hand. He puts the paper in his pocket. He takes it out again, then puts it back once more. He shuffles his feet.

“What’s wrong?” I ask. He is still not smiling. It jumbles me up.

“I can’t do this anymore,” he says.

I stare at him. What does he mean?

“They’re telling me,” he says, “that if I want to run my lending library here, I must get a permit.”

A permit?

“Can’t you get one?” I ask.

He shakes his head. “It costs too much. I can’t afford it.”

Then he says, “You want to give me back that book?”

He sounds so sad that I nearly burst into tears.

“I need to …” I hand it back to him.

I was going to say, I need to get another book. But before I can finish, Book Uncle takes the book from my hand. He puts it in a box. He picks up the box. He carries it over the broken pavement and stacks it on top of other boxes on his wooden cart. He does not even look at me.

He rolls the cart up the road — gada-gadaa, goodoo-goodoo. He does not look back.

Over the wall that circles Horizon Apartment Flats, I meet the eyes of the istri lady. She moves her iron up and down her board. She shakes her head.

“What happened?” I wail.

“Someone wrote a letter to Mayor S. L. Yogaraja,” says the istri lady. “It was a complaint. About our Book-ayya. Who would do a thing like that?”

The school bus is grinding its way towards my stop. I’d better go.

I don’t want to get on that bus. I want to chase after Book Uncle. I want to say, “Wait! There must be some mistake!”

Instead I have to run to the bus stop.

There is so much I want to know. What was in that pink paper? Who would be so mean to Book Uncle? Why would anyone write a letter complaining about him? And where are all his patrons who come and go, giving and taking books, day after day after day?

Can’t anyone help him?

I want to know all this, and there is no book that can tell me. What’s more, for the first time in four hundred and two mornings, I don’t have a new book to read.