WILDWATER UNLIMITED

In 1995, at the peak of West Virginia’s commercial whitewater activity, 225,000 raft customers whooped and hollered down the New and Gauley Rivers with steely-eyed raft guides behind them pushing rubber. There were days that year when a person could almost cross the river walking on rafts and never get wet. It was hard to believe that at the start of 1968, the number was closer to zero.

We can trace the roots of whitewater rafting in America to the 1800s, when the first rubber boats hit the water. While the earliest known commercial whitewater trips occurred in the latter part of the century, John D. Rockefeller Jr. created the first real river outfitter in 1956 on the Snake River under the shadow of the Grand Tetons. The public met his Grand Teton Lodge Company with a resounding yawn, but within a handful of years, they warmed to the idea. Following the lead of Rockefeller Jr., commercial river runners sprang up all over the western half of the United States. The East was soon to follow as outfitters appeared along the banks of a handful of rivers, including the Youghiogheny in Pennsylvania.

It is there where the story of commercial rafting in West Virginia really takes off. In November 1968, an unassuming but ambitious young couple moved from the Youghiogheny to the New River Gorge. Jon Dragan and Melanie Campbell would go on to birth an industry.

In one of his summers away from college, Jon worked for the Red Cross in Pennsylvania, teaching canoeing in its whitewater safety program. “That was where he really decided that he wanted to spend most of his life around water,” said Tom “Slick” Dragan, Jon’s younger brother by six years. “We were very fortunate, in that our parents traveled. They took us different places. We were just into canoeing and swimming, hiking and all that other stuff, and it was the natural progression over to whitewater rafting. There was no lightning bolt. It was a very slow progression over time.” Eventually, Jon found his way to Wilderness Voyagers, an outfitter on the Youghiogheny River, where he worked as a guide and helped the owners, Lance and Lee Martin, run their business.

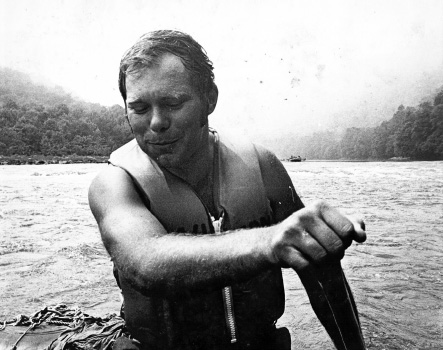

Jon Dragan sets shuttle for a run on the Youghiogheny River in Pennsylvania. Butch Christian Collection.

Lee Martin was also a Girl Scout canoe instructor. She had taught Melanie to paddle and invited her to join the organization, where she met Jon. “He was my knight in shining armor,” said Melanie. The two worked together often and grew fond of each other quickly.

An athletic, sandy-haired young man with an iron will, Jon soon became restless working for the Martins. He wanted to start his own company. It was the popular wisdom, however, that the “Yough” was full. “People didn’t feel that there was enough there for another family to be included in it,” said Melanie. In addition, though Jon and Lance worked together well enough, they were sometimes at odds.

Melanie Dragan, wife of the late Jon Dragan and mayor of Thurmond (population six), at her home next to the river that drew her and Jon to a depressed little corner of West Virginia to birth an industry. J. Young.

“The way I knew Lance,” said Tom, “he was laid back.” Both men were heavily into the outdoors, adventuring and having fun, but

Jon was aggressive. And I don’t mean that in a negative way. It’s just that when he saw something, he went after it. He did it as well as it could be done, and he did it because he made up his mind to do it. It’s as simple as that. They were two different people without a doubt.

That’s probably one of the reasons he ended up coming down South. I don’t think they would have ever worked well together long term. Short term, they both liked the river. Both were into good times. But as far as their business plans went—much different.

In 1967, Jon asked Melanie if she wanted to have a look at a river in West Virginia. Jon remembered running one a couple years earlier with John Sweet and a group of old C1-ers. “The Olympians,” Melanie called them. The group may have included John Berry and Bob Harrigan. “I said, sure, why not? What have we got to lose?”

The pair set out for the New River in southern West Virginia, but Jon wasn’t exactly certain where to put in or, for that matter, where the river was on a map. They drove into Fayette County on State Route 19 and finally entered the New River Gorge near the town of Prince. Jon pulled out his map, but the two still didn’t get their bearings until they spied a sign that said, “Thurmond 16 miles.” Still not entirely certain of whether or not they were even close to an appropriate put-in, but enjoying the adventure nonetheless, Jon and Melanie bumped their way down a dirt road in his pickup truck through the town of Thayer.

“On the other side of Thayer,” said Melanie, “we met a man named Shorty. He was a little guy. He lived in Thayer, and he was making his way to Mr. Pugh’s Grocery Store, which was in the Dunglen building,” on the other side of the river from Thurmond. From his grocery alongside the New River, Mr. Pugh sold basic food and fishing supplies and had a number of small shacks, which he rented to anglers.

Jon Dragan on the New River, 1969. Dragan Collection.

Jon and Melanie realized that the town was about midway along the river. “Jon went in and talked to Mr. Pugh and came back out and said, ‘Hey, he’ll rent us one of these little fishing shacks for five dollars a month.’ I said, ‘Take it!’ and we paid for a year’s worth.”

The next summer, Jon brought Tom, who was fresh out of high school, down for a look and “just to run the river and have fun,” he said.

“I think in the back of Jon’s mind, he had every intention of coming down here and doing something,” said Tom. “He was looking for someplace to go, where he could do a whitewater raft trip.” However, “I don’t know that. This is all hindsight, because we never talked about it in our family. We just did things.”

“I really thought the Upper New was boring and almost didn’t come back,” Tom continued. Then, they ran the Lower New. “I said, okay, this is good.”

Jon was hooked on the water in the New River and the wild area through which it flowed. He was also entirely smitten with the area’s unique coal history. The very next winter, Jon and Melanie came back for good and incorporated Wildwater Expeditions Unlimited before the New Year.

Wildwater bought two rafts, which were manufactured in West Virginia by a company called Rubber Fabricators. “There was no special design,” said Tom. “There were two Green River boats. We called them One Paw and Two Paw, because we took them up to my dad’s shop to paint them, and Jon had a St. Bernard. He stepped in a paint can, and put his paw down on the boat. Jon’s boat was One Paw, my boat was Two Paw and that was it.”

In their first season of operation, many of their customers were friends and relatives. It was also easier to get customers from the Pittsburgh area because, one, Jon and Melanie knew people there and two, Pittsburgh people knew about the Youghiogheny River. Many had paddled with Wilderness Voyagers and were looking for something bigger and better.

“But the numbers weren’t there,” explained Tom. “A trip with ten people…there were four of us as guides—Jon, myself, Chris [Jon and Tom’s younger brother], Mel and friends; Mel’s brother and sister. We probably had more guides than we did customers.”

Wildwater Expeditions Unlimited guides prepare near the foot of the Summersville Dam for a Gauley trip, circa 1971. Dragan Collection.

“We weren’t in it to make money.” continued Tom. “We weren’t in it to lose money, but it was more of a summer thing to do. You cut grass and run raft trips. You put a couple bucks in your pocket. We were also working for my dad during the school year. He had a construction company, so we were making money there. It was never about the money.”

Jon soon made friends in the West Virginia Department of Tourism, however, and managed to tag along with members of that office to several tourism expos. Jon and Melanie would pay their own way on the trips but could hand out Wildwater brochures, which at the time were simple mimeographed sheets. “We had nothing fancy,” said Melanie. “In 1970, my mom was the director of the Pittsburgh vocational schools, so they printed our first color brochure. It was something for the kids to experience.” Melanie also found work as a teacher north of Pittsburgh, and between that and help from their families, the Dragans were able to support themselves through the leanest times.

Wildwater built its tiny business around a two-day New River trip. The excursionists put in at Prince and rafted the relatively mellow water of the Upper New on the first day. They took out that evening at Thurmond, where they camped. And then the next morning, they floated the warm-up rapids into the bigger, heavier water of the Lower Gorge. During the week, Wildwater ran its office out of Thurmond.

Tom Dragan: “Wildwater boats rarely touched the ground.” Guides would lift them from the trailer and set them directly in the water. Dragan Collection.

The second year they were there, Mr. Pugh asked Jon and Melanie if they were interested in buying a home. “We thought it was really a great deal, because it had all these antiques in it,” said Melanie. Unfortunately, the antiques were gone when they moved in. Melanie still lives in that house.

Soon, Jon’s fascination with the area’s coal history made it into the trip itinerary as well. As time went on and customers began to show, Wildwater bought more boats, and the Dragans delved deeper into the abandoned towns that dotted the riversides. “We decided to make history as much a part of our raft trip as the whitewater was,” said Tom. “We started naming our boats after towns and people in them.” They began to require such knowledge in their guides, as well. “In order to work at Wildwater,” said Tom, “every year, you wrote a five-page, single-spaced paper on some facet of the history of the New River. Over the years, they did a lot of research. And our guides were just as much a part of the river trip as the river itself.”

“Jon loved history,” agreed Melanie. “We went to Williamsburg on our honeymoon! I can’t tell you how many times I’ve been to colonial Virginia!”

Melanie and the Dragans were the first Wildwater guides, but it wasn’t long before they needed help and began to seek out others. Jon was again taking college classes, this time at California State Teacher’s College in Pennsylvania. He found other boaters there and convinced them to come down. “We also had a lot of weekend warriors,” said Melanie. “Jon would meet people and say, ‘Hey you want to be a river guide?’”

“They trained all the time. They trained in the evening when they came off the river. They did throw ropes. They did knots. We used to go through a whole week of training classes,” remembered Melanie. Jon even brought in a snake expert to lecture and teach the guides to identify snakes. A rope-access expert, Bruce Smith, taught all the knots, ropes and z-drags. Jon even anchored a tire tube in the middle of the river for guides to practice with throw ropes. “If they got it right in the middle,” said Melanie, “they got a beer or something. There was always some sort of incentive.” Guides learned first aid and CPR, too. Wildwater hired EMTs to come and teach.

One of the first local West Virginians to become a Wildwater guide was Bob Underwood, who had spent lazy summer days as a boy floating down the New River in homemade wooden boats. “I heard they were running the New River,” said Underwood. “I just said, well, I think I’ll go down and talk to them, since I grew up down there. I said, ‘I’d like to run the rapids with you two guys.’ I explained that I grew up here, and that I knew some about the river. So, Jon said sure.” Dragan told him a time and place to meet, and before he knew it, Underwood had run farther downstream than he ever had before.

Wildwater was growing quickly, so the Dragans added more boats, this time New River rafts, which, like the Green River rafts, were Rubber Fabricators creations. At twenty feet long, sporting twenty-four-inch-diameter outer tubes and four sixteen-inch-diameter cross tubes, the New River rafts were humongous. “Depending on how many people you had and their weight,” said Underwood, “it was almost like loading an aircraft. If you had a whole bunch of people that were a little overweight, you would have to distribute that weight around just so you could paddle the boat down the river.”

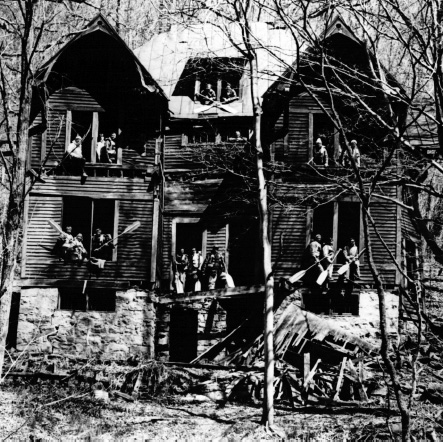

Wildwater guides at the Caperton House in the Caperton ghost town of the New River Gorge. Jon Dragan made sure that all his guides knew as much as possible about the cultural history of the New River. That practice continues at several raft companies today. Butch Christian Collection.

Wildwater developed a two-guide method to muscle the behemoths downstream. The stern guide—also known as the long-range person—was responsible for looking downstream, assessing the level of the water and the rapid itself and lining the boat up far before it actually arrived at the rapid. He or she needed to set the boat’s angle correctly and put it in the flow so when it entered the rapid it was in the best location relative to the current and pointed the right way. The bow guide was the short-range person. He or she moved the boat through the rapid itself. “If you were lucky enough,” said Underwood, “you had two up front.”

Before adding the big boats, the company was still being stymied by occasional high water, which the Dragans viewed as too dangerous to run. “Safety was a priority to Jon,” said Melanie. “When the river got above five feet, we didn’t run it. So he tried to figure out ways he could take people down and experience the trip.” The New River rafts weighed 450 to 500 pounds. “The tubes got bigger because they figured they could run at a higher level.” The new boats increased Wildwater’s cutoff from five feet on the river gauge to nine.

It was only the beginning. “We tried triple rigs, which were three Green River rafts lashed together side by side, and a person sat in the middle with these two huge oars,” recalled Melanie. “But what happened was, when you get in someplace like Keeney’s Creek, the middle boat goes into a hole and the outer boats would buckle, and you had no control! So, we never ran commercial trips in triple rigs. The guys tried lots of methods, and that’s when they came up with the pig rigs.”

Pig rigs were pontooned catamaran rafts with aluminum frames strapped atop, seats and even a railing to keep people in. They also sported fifty-horsepower Mercury motors—no paddles necessary. “We did trips in the wintertime when we got those, and we were also able to walk into the old towns then because we didn’t have to worry about snakes.” Pig rigs could haul sixteen people. The motor did all the work.

The water level would determine how high upstream they put in with the pig rigs. When the New River was high and fast, “we would go to Prince or Sandstone or wherever, so customers got the whole day on the river,” said Tom. “Sometimes we’d combine that with a trip to the expedition mine, and then Prince to Thurmond, eat lunch at Thurmond, then to Fayette Station, so when people made the effort to come, they got a full day’s entertainment.” Wildwater eventually had five pig rigs, which it also began to rent to other outfitters. “We only flipped one. Jeff Proctor [a principal owner of Class-VI] was in it. I think the Park Service bought one. Chris had one. I think he even still has one left.”

The company even experimented with mule trips in the winter. “Jon tried all kinds of new ideas to bring people into the area. It was hard in the beginning, because people didn’t know what whitewater was. Jon was always trying to find a new idea to build an industry,” said Melanie. “He was always looking for ways to make things better. He was very innovative. He was the idea person.”

Nick Rahall, the Democratic congressman from West Virginia, interacted with Jon often after he was elected to office and had begun to work on creating the New River Gorge National River. He remembers Dragan as “a determined individual! Very persistent. He was responsive to every question that was raised of him and not willing to take no for an answer. A dogged determination that has benefited our area untold number of times over.”

There was, however, “no grand scheme, despite what some people think,” said Tom. “Class VI, MRT, they might be different, they might have sat down with a business plan. We were just doing things we liked to do, and it worked out.”

“We didn’t have much at Thurmond base camp until the early ’80s,” said Tom. “I mean, it was a horse field.” They kept the grass cut and hung oil-filled lanterns in front of tents, in which many of their customers slept. “And everybody just hung out and had a good time,” continued Tom. “We’d get up at seven in the morning, have breakfast, do the safety orientation and put in on the river.” Wildwater trips were on the river at ten minutes to 8:00 a.m. every day. They didn’t take out until 4:30 p.m., sometimes 5:00 p.m.

At the time, there was no midpoint access at Cunard. “I don’t care if the water was eight feet or two feet or minus two,” said Tom. “You put in at Thurmond, and you beat your brains out getting down there. You swam, you paddled, you told jokes, you told history. It was as laid back and outdoorsy as you could get.”

Wildwater’s first commercial Gauley trip was in September 1971. Melanie remembers it well, because “we were supposed to be married the weekend of the twenty-fourth and twenty-fifth of September. Then they received word from the Corps of Engineers that they were releasing water, and I had to change my wedding date to October.”

Those early Gauley Wildwater trips were also two days long but, curiously, didn’t involve much camping, other than at the put-in. Trips paddled halfway down the river, and then Wildwater hauled them out, picked up guides and guests at Panther Mountain and took them back to camp at the dam. “We would literally move our base camp from Thurmond to the dam,” said Melanie. “After a while, we figured what the heck, we’ll just stay in a motel, and we spent a lot of time eating at Country Road Inn. That became just as much a part of our trip as the river.” Guides and guests alike wined and dined all evening, and then Wildwater hauled everybody back to the river the next morning to complete the trip.

“Every day was an experience,” said Tom. “There were no rules. There were no books. You could do whatever you wanted, as long as nobody got hurt.”

“Unfortunately, it did evolve into a business,” said Tom. “When it evolved into a business for us, that’s about the time other people started to come along. And then—I’m not saying it wasn’t fun—but there was another aspect to it that we didn’t necessarily buy into for whatever reason: the competition.”

Before West Virginia built the New River Gorge Bridge, a commute to and from the Gauley River from Thurmond was a major affair. Wildwater dodged the problem by camping at the dam, circa early 1970s. Butch Christian Collection.

As new companies began to join the fray, Jon’s personality, which some viewed as coarse, would again come into play. Jon would eventually find himself at the center of the New River rafting industry’s biggest controversy, which revolved around Wildwater’s ownership and control of Fayette Station, a convenient takeout point upstream of a grueling flat-water section called Hawk’s Nest Lake. That was not, however, the only time he was at odds with others on the river.

“Jon would normally put in early,” said Paul Breuer, owner and founder of the New River’s second (or is it third?) rafting company, Mountain River Tours (MRT). “We’d never see him.”

One day, however:

We had an early trip for some reason. We were on Jump Rock, and here comes Jon with eight or ten rafts and he surrounds us. We couldn’t jump! Jon got on my raft and said, “That’s my rock! Get off my GD rock!” I said, “I don’t see any signs, and by the way, you’re on my raft. Get off my raft!” And that was basically the start of our conversations for another ten years.

Breuer remembers another Dragan story that involved his friend Bob Morgan, who is himself a major figure in New River rafting history. A Morgan trip camped at Stone Cliff, intending to put in again the next day, but overnight, the water rose to an unacceptable level, and the group had to cancel. Dragan was there that day, and Breuer left him and Morgan at Stone Cliff while he shuttled customers back to MRT’s base in Hico. When he left, the two men were calmly discussing how to run the river. “I remember coming back and seeing both men standing on rocks or trailers,” said Breuer, “not on the ground. One was trying to get higher than the other, arguing about how to run the river. I could hear them from a quarter mile away. It went on and on, and finally I said, ‘Hey guys, I want to go home.’”

Despite his sometimes abrasive nature, Jon continued to lead Wildwater into successful currents. Neither he nor Melanie and Tom, however, were completely happy with the competitive state of the industry. “We did really well in the outfitting business, until about the early ’80s,” said Tom.

That’s when I think it got competitive. Even in the late ’70s, Class-VI came along, and things were going pretty good. And then all of a sudden, to me it got, not cutthroat, but it was probably more important to get people to come to your facility to take them down the river, so you could make more money, than it was to just go out and run the river.

By 1984, the Park Service began to make offers to buy Wildwater’s land so it could add the parcels to the park. “And for me,” said Tom. “I was ready to get out, because I wasn’t interested in competing with all the other outfitters and to cut corners just to make more money. So, we found other things to do.”

In 1990, Wildwater sold three pieces of land to the National Park Service, including thirty-odd acres at Stone Cliff above Thurmond, five acres at base camp and five or six acres at Fayette Station. “We had been talking to them for about seven or eight years, telling them no, no, no,” said Tom. “They finally came up with a price that was more than fair. At that point, Jon and I probably knew we were getting out of it. I had two sons and a wife, and rafting takes a lot of time for seven months out of the year. It was an easy decision for me.”

After cutting the deal with the Park Service, the Dragans began to look for a buyer for the company. Jon, Melanie and Tom sold their interests in Wildwater in 1990. “Chris decided he had plenty of time left,” said Tom, “and he became part of the new Wildwater.” The company continued to operate out of Thurmond for two more years, before moving operations downstream to Lansing.

What Jon, Melanie and Tom left behind was a thriving industry rapidly approaching its peak and running tens of thousands of happy people down the river each year. Tom is still adamant that none of it was planned and that from his family’s perspective, everything was for the most part done spontaneously. Of Jon, however, he also said, “Once he set his mind to something, he did it. It all was his idea, without a doubt.”

Jon Dragan, who was larger than life, outspoken, dedicated to the history of the New River and the father of the West Virginia whitewater rafting industry as we know it, passed of stroke in February 2005 at the all-too-young age of sixty-two. I never met him, but I feel like I know him just a little, and I miss him.