8

Why do you interrupt so much?

I have interviewed every prime minister since Alec Douglas-Home who occupied 10 Downing Street for a year from October 1963. That’s more than half a century’s worth. It’s almost possible to chart the recent political history of the country through those encounters:

- the ‘white heat of technology’ promised by a young Harold Wilson;

- Ted Heath’s success in taking us into Europe;

- the winter of discontent under Jim Callaghan;

- Margaret Thatcher’s mission to tame the trade union bosses;

- John Major’s mission to slay the Eurosceptic ‘bastards’ in his own party;

- the dawn of ‘New’ Labour under Tony Blair which made him so many friends outside the Labour Party and his decision to take us to war in Iraq which lost him those friends;

- Gordon Brown’s mistaken insistence that Britain had ended the ‘boom and bust’ economic cycle;

- David Cameron’s humiliating failure to persuade our European partners to cut Britain some slack so he could persuade the country we should stay in Europe – and then, when they sent him home with a flea in his ear, his decision to call a referendum;

- Theresa May’s failure to persuade Parliament that she had the right plan for Britain’s departure from the European Union.

If there is a single common factor among those nine prime ministers I suppose it’s that they all started out with much of the nation reposing at least a modicum of hope and trust in them and most ended up with the nation wondering why. That tends to support Enoch Powell’s view that all political careers end in failure – though he might have been more accurate if he had said all prime ministerial careers end in failure. We’ll probably all remember Thatcher for her disastrous poll tax and Blair for his infinitely more disastrous Iraq adventure rather than for the fact that they were each the most successful leaders of their parties in electoral terms since the Second World War.

But in spite of that – or, more realistically, because of it – the interview with the prime minister is invariably the one that all current-affairs programmes hanker after. No matter how often prime ministers are interviewed on Today it’s always regarded as something of an event – and so it should be. It’s a pretty scary event for the presenter. If you make a mess of an interview with a junior minister there is always the consolation of knowing you’ll be doing another one tomorrow and you can make amends then and anyway nobody really notices. If it’s the prime minister, everyone notices. There’s something about the office of prime minister that makes it pretty daunting even if you’ve been doing it for as long as I did. And it is still a pretty rare event. For every one interview that was granted we probably bid for another dozen.

Mostly we shrugged our shoulders when Number 10 said no and took the view that it was worth a try. We knew the bid would almost certainly fail to get past whoever happens to be the Downing Street spin doctor, let alone end up on the boss’s desk. If prime ministers accepted every interview bid they’d barely have time to brush their teeth in the morning, let alone actually run the country.

Even so, we often got cross when our bid was turned down. The Today programme is not overburdened with modesty. It sees itself as far and away the most important current-affairs programme in the country and assumes that everybody who is anybody in public life takes the same view.

Sadly prime ministers – or at least their spin doctors – tend to see the downside as well as the upside and, sadly, we don’t have the power of subpoena. With politicians further down the greasy pole it’s easy: they need us more than we need them. But the opposite tends to be true of their bosses. If the health secretary is making an announcement that waiting lists have fallen by 0.01 per cent and his spin doctor offers us an interview – preferably at 8.10 – we will probably say thanks but no thanks. If, on the other hand, waiting lists have increased by ten per cent and the health service is (once again) ‘in crisis’ we shall be hammering on their door. And they will almost certainly say the health secretary’s diary is crammed full for the foreseeable future. That applies whoever is in power.

What does change is that programmes like Today fall in and out of favour with different party leaders. Until relatively recently, for instance, all the party leaders were happy to give us an interview at some point during the party conference. That was until Jeremy Corbyn took over the Labour Party. He – doubtless encouraged by his director of communications Seumas Milne – regarded us with profound suspicion and gave us a wide berth. In the five years after he became leader I interviewed Corbyn precisely once. That may be because he made a bit of a mess of the interview, which he did, and Milne calculated he was much safer talking to the party faithful or soaking up the ‘Oh Jeremy Corbyn!’ chants at the Glastonbury festival. Which he was.

But generally opposition leaders are far more willing – eager, even – than prime ministers to appear on Today and the same goes for the shadow Cabinet members. There’s an obvious reason for that. When politicians are in power they do things. They have no choice. And when some of those things go wrong, sooner or later they have to face the music.

The difference with opposition politicians is that they cannot do things: they can only talk about doing things. So there is not the same imperative. Power changes the equation. It’s different when we are approaching an election and they have to publish their manifestos. Then the interviewer can, for instance, demand to know how they intend to keep their promises of building more hospitals, making the trains run on time and providing a nice new semi for every young couple while simultaneously cutting taxes. It’s also important to allow them a platform to criticise the government – which is the one thing oppositions can do.

We are inevitably attacked by each side for going soft on the other. That’s part of the job. Sometimes the criticism is justified but when we got it wrong it was, at least in my experience, unintentional. We tried hard to keep a balance. By ‘we’ I mean my colleagues on the Today programme. There is a much bigger question over whether the BBC as an institution is truly impartial and I want to address that later in this book. Whether we succeeded on the Today programme is more straightforward.

Mostly it’s a matter of judgement by the editor, and editors need to be made of pretty stern stuff. They get it in the neck from all quarters: whingeing presenters, the big BBC bosses and politicians. Above all politicians – because if they upset them too much they upset the bosses too. When Greg Dyke was the director general during the Blair government years he gave evidence to the Lords for the BBC Charter Review on 6 April 2005. This is part of what he said: ‘If you are the news department and Alastair Campbell writes in … two or three letters a week for month after month – I can remember the head of news saying to me at one stage “I have had another letter from Alastair” (and they were rants, at times: you could not always work out what the complaint was) – it inevitably conditions how you respond.’

‘Let’s stop now, John. They’ve been grilled enough.’

The chairman of the BBC Gavyn Davies said at the same hearing: ‘We heard frequently from Alastair Campbell at different levels of the BBC, and it became an almost incessant drumbeat of complaint. We emphatically felt that we were put – not just the two of us but the BBC as an organisation – under pressure to cover the [Iraq] conflict in a way we did not think was fair.’

The pressure is at its greatest during general elections. Once an election has been called, the BBC is required by law to ensure that the political parties are covered proportionately during the course of the campaign. It keeps a log of who has been interviewed, and for how long, and checks the figures on the database once or twice a week. The appropriate amount of coverage for each party is largely determined by how it performed at the last two elections.

At the same time, normal news judgements apply and any kind of appearance can count towards the running total. On this basis, we could, I suppose, interview a Tory politician for six minutes about allegations that he used public money to take his beautiful young assistant to the Caribbean for a long weekend and then interview a Labour politician for exactly the same time about how she rescued a drowning toddler from a lake, and the same figure would be added to the total for each party. For the purposes of the database, it perhaps means that there really is no such thing as bad publicity, though in this case I rather doubt the Conservatives would agree. The fact is that ‘balance’ – or ‘due impartiality’ as we are meant to think of it – is in the eye of the beholder.

Once again 8.10 is the high-status slot and some will refuse to appear unless they get it. Often it’s granted on the basis of seniority. The higher up the Westminster pecking order, the greater your chances. Fair enough if you are the Foreign Secretary or the Chancellor of the Exchequer and you have something interesting to say. But if you haven’t? There may be a few listeners who want to hear an interview with the chancellor just because he is the chancellor, but I doubt there are many.

Another mistake we’ve made over the years has been to favour politicians. Again why? Fair enough if there’s a strong political story leading the news or if something big is happening somewhere that demands a reaction from the government, but it’s too often a knee-jerk response on our part. In the early days of computing the old saying went: ‘Nobody ever got fired for buying IBM.’ On Today it has become: ‘Nobody ever got fired for giving the 8.10 to a politician.’ Well maybe they should have been. Or maybe the presenter should get fired for doing a boring interview.

Politicians are sometimes wary of the 8.10 for the same reason that they are sometimes so keen to be offered it: they get lots of airtime. It is invariably the longest interview on the programme. There is something all politicians have in common: they love the sound of their own voice. But, to be fair, they also like the extra time because if they really do have something important to say they can say it without being hurried along too much. The downside is that the interviewer has more time to challenge them – which means they need to do their homework and if they are trying to pull a fast one there is a much better chance they will be found out. Either way politicians generally find it more difficult to turn down a request for an interview on Today if they are offered the top slot.

I recall only one exception: a senior politician who regularly found an excuse not to appear in the studio at 8.10 but would offer himself for the 7.50 instead – the slot immediately after ‘Thought for the Day’. He was Sir Geoffrey Howe, Chancellor of the Exchequer at the time and, if I’m being entirely honest, not a serious contender for the title of most entertaining performer in the great Palace of Westminster. Not for nothing did Denis Healey (himself a brilliant performer) suggest that being attacked by Howe was like ‘being savaged by a dead sheep’. He was, almost without exception, an extremely boring interviewee. He delivered his thoughts with all the verve and panache of a priest delivering the last rites. But something curious happened during his 7.50 Today interviews.

For the first five or six minutes he would drone on in his usual way, giving a passable imitation of a man who’d just been told his dog had died, and then he would look up at the clock on the wall opposite him and behave as though he’d had half a pint of adrenaline injected into his plump arm. It might be a passionate denunciation of something he was supposed to approve of or the announcement of a policy shift he knew would provoke some heated debate. And when he had finished he would look back up to the clock, give what passed in Geoffrey’s case for a small smile, and stop. At last something meaty for the presenter to get his teeth into. Something to challenge him on. Except that you couldn’t because there was no time left.

Some years later, when he had long since stopped running the nation’s finances, Geoffrey confessed all. He preferred the 7.50 slot, he told me, because he knew exactly when the interview would end. That’s because it was followed, of course, by the weather forecast and if there was one thing in those days before smartphones that the listener would not tolerate it was being denied the weather forecast. I often think that’s the only thing half our audience really listened to. And clever old Geoffrey knew that. Let others enjoy the limelight of the 8.10: he knew exactly what he was doing. And it worked.

When he retired and wrote his memoirs Robin Day gave the book the title Grand Inquisitor. He had earned it. An obituary written by a politician, Dick Taverne, said he had been ‘the most outstanding television journalist of his generation. He transformed the television interview, changed the relationship between politicians and television, and strove to assert balance and rationality into the medium’s treatment of current affairs.’ Things were very different before Robin and his contemporary, the formidable Alastair Burnet of ITN, came along. An interview with the Labour leader Clement Attlee began with this killer question: ‘Can you tell us something of how you view the election prospects?’

Short of actually polishing politicians’ boots, or maybe even licking them, we could scarcely have been more deferential. When the Today programme began in 1957 there was no problem with political interviews because we simply didn’t do them. It was Robin himself who had originally suggested the idea of a current-affairs programme at breakfast time on what was then the Home Service. It started life as two twenty-minute segments of ‘topical talks’ and for years it never quite shook off its fondness for the lighter side of life. John Timpson, who presented the programme from 1970 to 1976 and again from 1978 to 1986, was fond of making jokes about the news – ‘Insulation – Britain lags behind’ or ‘Crash course for learner drivers’.

But largely thanks to Robin, we moved from the days of ‘Is there anything else you’d like to add, sir?’ to the no-holds-barred, ‘they don’t like it up ’em’ approach. Early in his career, during the 1964 general election, he set the ground rules for us all in an interview with Labour’s deputy leader George Brown about the potential nationalisation of the steel industry by the newly elected government.

RD: Would you care to comment?

GB: I have already done it. My good gracious me, Robin, you don’t seem to listen—

RD: I do listen Mr Brown.

GB: Well then I don’t know why you repeat the question.

RD: I didn’t ask you that question before.

GB: Yes but I—

RD: You may be a member of the new administration, Mr Brown, but I’m still entitled to ask you whatever questions I like that are reasonable.

A generation later we had the great Brian Redhead carrying the torch on Today. I had the pleasure of sitting alongside him when he launched into the monetary policies of the then Chancellor of the Exchequer Nigel Lawson. Lawson had made the mistake of chiding Brian for his political bias. A lesser interviewer might have tried to ignore what was a serious charge from a senior politician. Brian did not miss a beat.

‘Do you think we should now have a two-minute silence in this interview Mr Lawson? One for you daring to suggest you know how I vote and secondly perhaps in memory of your policy of monetarism which you have now discarded.’ Lawson made no real attempt to defend himself. He knew he was beaten.

There’s nothing wrong with a bit of theatrical knock-about even on a programme with such a strong political agenda as Today. And every interviewer has a favourite interviewee – somebody who would often prefer a bit of a punch-up rather than revert to speak-your-weight mode. I (almost) always enjoyed interviewing Ken Clarke, for one. How could you not warm to a Chancellor of the Exchequer who admitted that he was unable to answer a particular question on the vitally important Maastricht Treaty, the most important EU document of the time, because he hadn’t actually got around to reading it?

Michael Heseltine was another favourite. We became such a regular feature on Today when he was deputy prime minister that the Guardian ran a leader column making the case for an end-of-pier show: The Humph ’n’ Hezza Show. John Prescott was another – even though it wasn’t always possible to follow his every word. It was said of Enoch Powell that he never began a sentence without knowing exactly how it would end. With Prescott it was the exact opposite. He once rescued the Labour Party leadership from a serious defeat at a party conference with a brilliant, unscheduled last-minute speech. As it happened I’d arranged to have breakfast with him the following morning. When he arrived I told him what a great speech it had been.

‘Yeah, I know …’ he growled, ‘but what did I say?’

I’m pretty sure he wasn’t joking. Nor was he when he was the environment secretary and I asked him about some serious problems he was having over his approach to preserving (or failing to preserve) the green belt. He was having none of it.

‘The green belt is a great achievement,’ he expostulated, ‘and this government is going to build on it!’ Everyone knew what he meant – even if the words didn’t quite work.

The point about all three of them is that they engaged with the interviewer and thus with the audience. There is almost nothing that annoys the listener more than the politician who ignores the question and simply repeats what he told you thirty seconds ago. I use the word ‘almost’ because there may be one thing the audience finds even more irritating: the interviewer who interrupts so much the politician has no opportunity to make his point.

Clearly there’s a balance of interests here. We need the politicians to fill our programmes; they need us to promote their careers, appeal to the voters, or simply because, as elected figures in a functioning democracy, they feel it’s their duty to appear. One senior Cabinet minister once opined that if he’d had a bad day as a minister and the press were on his tail, he would volunteer to go on Newsnight to deliver his message in the hope of catching the final editions of the papers. If he’d had a good day, the thought of travelling across London late at night to be skewered by Jeremy Paxman held rather less appeal.

The former Labour Foreign Secretary Robin Cook was one of that rare breed of politician who chose to resign on principle rather than cling on to power and all its trappings. For him the breaking point was Tony Blair’s decision to go to war against Iraq in 2003 but he and I had many lively exchanges on Today. Robin was a brilliant man – many said that in his prime he was easily the best debater in the House of Commons and I approached every interview with him with more trepidation than confidence. So I was astonished (and, yes, a bit flattered) when he wrote in his memoirs years later that the only thing that kept him awake at night was the prospect of being interviewed by me on Today.

For such a successful politician Robin had remarkably little self-confidence. He phoned me at home one Sunday afternoon because, he said, he’d heard I was friendly with Rory Bremner, arguably the greatest political impressionist we’ve ever had. I told him that, yes, I considered him a friend. And the conversation went something like this:

‘Why is he so horrible to me on his television show?’

‘Because you’re the Foreign Secretary and he’s a satirist and that’s what he does.’

‘But he makes it sound as if he really doesn’t like me …’

How extraordinary that one of the cleverest and most powerful ministers in the government should worry about a bit of mickey-taking on a show designed to do just that. I tried to console him but I don’t think I succeeded. I’d had a taste of Robin’s insecurity when John Smith, the leader of the Labour Party, died suddenly of a heart attack in May 1994. He was one of the three being tipped as a possible successor.

A few weeks before the date for nominations closed I found myself in the gents’ toilet in Broadcasting House with Robin. I asked him if he was in the running. He said emphatically not. So, obviously, I asked him why. We were washing our hands at the time in front of large mirrors.

‘Look in the mirror!’ he told me.

‘Yes … so what?’

‘I’m too ugly. This is the television age.’

It’s true Robin would never have been mistaken for George Clooney – there was a certain gnomish quality to him, but I repeat: so what? It’s an immensely sad reflection on all of us if a politician of his quality has to rule himself out of the leadership because he’s ‘too ugly’.

As for our approach to interviewing politicians, I fear that we may have travelled too far from the days of deference to an era of open combat. I would not presume to claim the title ‘Grand Inquisitor’ – that will always belong to Robin Day – but I have had the rather more dubious honour of being dubbed a Rottweiler or Welsh terrier for what many have seen as my overly aggressive interviewing. Mostly the BBC have shrugged it off and simply pointed out that I was only doing my job – if occasionally rather too enthusiastically. But there were times when the complaints came from sources that could not be lightly dismissed. One of the most potentially dangerous came soon after Labour had taken power in 1997. I became an official ‘problem’.

It happened after an interview I had done on lone parents’ benefit with Harriet Harman, who was the new secretary of state for social security. Within hours of the interview being broadcast the Labour Party’s director of communications, David Hill, wrote to my editor and said: ‘The John Humphrys problem has assumed new proportions. We have had a council of war and we are seriously considering whether, as a party, we will suspend co-operation when you make bids through us for government ministers.’

This of course was a real threat. What sin had I committed? You may not be surprised to hear that I had apparently interrupted Harriet too much. Mr Hill called it a ‘ridiculous exchange’ and said that because of the repeated interruptions no one would have been any the wiser as to Harriet’s explanation of government policy. She made no complaint herself and my editor, Jon Barton, came to my defence: ‘I felt this morning that I was listening to a rigorous, fair-minded interview which illuminated an important policy issue.’

It may say something about my lack of self-awareness that after I’d finished the interview I had not given it a single thought. Yes, it was fairly lively, but no more so than a hundred others I’d done in the past weeks and months. So I was astonished by the reaction from 10 Downing Street. I had not been aware that there was thought to be a ‘John Humphrys problem’. On the contrary, it was only a few months earlier that the Labour Party had been praising me for my robust approach in trying to hold the Conservative government to account. Was it really possible to have undergone such a dramatic transformation in such a short period of time from staunch defender of democracy to the ‘John Humphrys problem’? From hero to villain in the time it took for the nation to put a cross on a ballot paper.

The obvious answer, or so I told myself, was that it wasn’t me who had changed. It was the Labour Party. After so long in the political wilderness they were now in power. That transition can do mighty strange things. Instead of attacking the government’s policies, as they had been doing for eighteen years, they had to defend their own. And of course it wasn’t just the opposition doing the attacking. It was the media as well. Not because people like me had a particular axe to grind but, as I suggested earlier, it is governments and not oppositions who make policies and therefore become our natural target. In other words, it’s all about holding power to account.

The Harman row foreshadowed the start of a much more confrontational relationship between Downing Street and the media and at the top of their hit list was the BBC. Alastair Campbell recognised that in one important sense its reporting mattered more than newspapers. Most Daily Mail readers had already made up their minds which way they would vote and so had most Guardian readers. The chances of changing their minds were slim to non-existent.

The BBC is trusted by most people to be impartial in a way that the papers are not. We have no choice in the matter. Nor should we. So in terms of winning hearts and minds, there was everything to play for. Thus the logic went. And the Harman row was but a light breeze compared with the hurricane that was to follow over our coverage of the way Blair handled the Iraq War in 2003.

But things were already growing tense as we approached the election of 2001. Labour simply withdrew co-operation from us. It got so bad at one stage that I was asked to explain to the listeners that the reason we might appear to be struggling to give a balanced picture was because the government kept turning down our requests to interview ministers. My editor Rod Liddle blamed the ‘paranoia of the press officers in Millbank’.

If nothing else it proved, yet again, the hypocrisy of politicians who love to extol the vital function of a free press. What many of them mean by ‘free’ is the freedom to praise their own party and rubbish the opposition.

After Rod had left the programme for a brilliant career as a columnist he wrote: ‘Our government really, really hates the man [Humphrys] and it is being aided in its campaign by one or two sycophantic News International journalists and one or two naive or envious souls from within the BBC itself … Labour does not like the relentless and forensic manner in which Humphrys (and, for that matter, Paxman) conducts interviews with government ministers; the refusal to sanction obfuscation and – you have to say – on occasion downright lying.’

But I can’t pretend that it was only politicians who complained about my style of interviewing. Whenever I met listeners out there in the real world the same two questions were inescapable.

Why do you interrupt so much?

Why do you give politicians such a hard time?

My answers to both were always much the same. I interrupt when we are short of time (which we often are) and when politicians fail even to try giving a straight answer to a reasonable question. When that happens the interviewer is entitled, even obliged, to press for an answer. If that means sometimes interrupting them when they are in full flow, so be it. It beats yet another party political broadcast. But I’ll have more to say about that later.

It’s relatively rare to get a call from one of the bosses at home. It’s almost never good news. By ‘bosses’ I mean those people who don’t actually make programmes but whose job is usually to make life difficult for those who do. There are rather a lot of them in the BBC. The call I got on the evening of 24 March 1995 was about as bad as it gets.

It came from Steve Mitchell, the head of radio news programmes, a decent man who became a good friend over the years. His mild, almost apologetic manner concealed a sharp brain and a tough character. We’d had a few run-ins over the years but nothing too serious. What he was about to tell me was, for the BBC, very serious. For me it was perhaps even the end of my short career on the Today programme.

Steve had just been told about a speech that was being made that evening by a Conservative Cabinet minister, Jonathan Aitken. Aitken was a colourful character who had made his name in journalism and as a television presenter before he went into politics. He was a risk-taker: a debonair Old Etonian who had been acquitted at the Old Bailey of breaching the Official Secrets Act, triggered the wrath of Margaret Thatcher by capturing the heart of her daughter and renouncing her for another woman, and making an enemy of the formidable Anna Ford. He had been instrumental in relaunching TV-AM and firing its presenters. Anna was one of them. She repaid him by throwing a glass of red wine over his head at a cocktail party. Now Mr Aitken had me in his sights – and he fired both barrels.

In Aitken’s eyes I had committed two great offences. The first was to chair a meeting in Westminster of teachers opposed to the Conservative government’s pay policies. I’d been assured when I agreed to do it that both sides of the argument would be represented on the platform, but they weren’t: just Labour and the Liberal Democrats and no Conservatives. I was completely impartial in my questioning, but my very presence on the platform gave Aitken the ammunition he needed. I had ‘embraced open partisanship’, he claimed. It had been a ‘bizarre breach of the normal convention that political journalists stay out of partisan politics’, he thundered. It wasn’t true but it might possibly have looked that way to anyone who wasn’t actually present at the meeting.

His second charge was ludicrous. I was ‘poisoning the well of democratic debate’ with what he called my ‘ego-trip interviewing’. This was Aitken at his rhetorical best and his irrational worst. For a BBC presenter it is hard to imagine a more damaging allegation. So what was his evidence?

It was an interview I had done with Ken Clarke, then Chancellor of the Exchequer, some weeks earlier. Aitken accused me of having interrupted Clarke no fewer than thirty-two times in a fairly short 8.10 interview. In the narrowest possible sense he might just have been right. There were certainly plenty of interjections – but it rather depends on what you mean by ‘interrupt’. I have always thought an interview should be as close to a conversation as it’s possible to get.

In the very early days of current-affairs programmes on the Home Service it was rather different. The BBC man (always a man) would have all his questions written down and ask each in order. He would wait for the answer to be completed and then, regardless of what his interviewee had said, would ask the next one. No follow-up, no challenging of any dubious claims, no expression of scepticism. It’s quite a long time since we took that approach and I rather doubt that even Mr Aitken would want to return to it. But perhaps I’m wrong. The obvious point here is that there is a real difference between interrupting for the sake of it and interjecting to try to keep the interviewee to the point if he has wandered off. And there is an even more important principle at stake.

Let’s be clear about why we ask politicians onto the programme – apart from the fact that they come free. It is categorically not so that they can deliver a party political broadcast, which is what we’d get if we never interrupted them. It is our job – our duty – to try to hold power to account. And if we ask them the questions we believe our audience wants answered we are entitled to persist. That’s our job. You might argue that it’s often their job to duck the questions and I would agree. If I ask the chancellor a month before the Budget whether he intends to put up income tax he’s absolutely entitled to tell me to clear off. MPs are the first to be told – although so much leaking goes on these days that one sometimes wonders whether there’s any point in bothering with the formal announcements on Budget day. But that’s another matter.

What I don’t believe politicians should be allowed to get away with is refusing to answer a perfectly reasonable question. Not that they ever ‘refuse’ as such. They have a dozen different formulas for not answering without ever actually saying: ‘I’m not going to answer that question.’ You might recognise a few of these old favourites:

‘I really don’t think that’s what your listeners are concerned about …’

‘What your audience really wants to know …’

‘This government is on record as having said …’

‘We are absolutely clear that …’

And so on ad infinitum.

Even more annoying is when you ask them why their party is making such a mess of whatever it happens to be and they insist on telling you, over and over again, why the other party is even worse. The other dreary old tactic is to pretend they have answered the question when they patently have not. Yet another is simply to repeat what they have already said, knowing that the interviewer will have to give up eventually either because there’s no time left or because he has simply lost the will to live. It goes something like this:

‘Minister, why is the government cutting benefits to people who are struggling desperately to make ends meet?’

‘This government has always believed that the vast majority of people in this country want decent jobs that pay a decent income.’

‘Indeed … but some people are forced to rely on benefits and they are now facing real poverty.’

‘We are proud of our record, unlike the last government, of building an economy in which there is work available for everyone who wants to do it.’

‘My question is about welfare benefits.’

‘And I am trying to make the point that there are many, many hard-working people out there who have benefited enormously from the opportunity to earn a decent living which means that they do not have to rely on benefits.’

‘And I’m trying to ask you about the cuts to the benefit system …’

‘Let me repeat … the ordinary, decent, hard-working people in this country take pride in their work and we want to make it possible for them to do that work by ensuring that the economy is robust and works for everyone, not just the few …’

And so it goes. You will have heard a version of that interview a thousand times. I would suggest that when we interviewers are faced with that sort of non-answer we are entitled to interrupt. But Jonathan Aitken was doing more than attacking me for interrupting. He said: ‘Mr Humphrys was conducting the interview not as an objective journalist seeking information, but as a partisan pugilist trying to strike blows.’ Now this is a potentially lethal accusation.

There is nothing wrong with partisan journalism or campaigning journalism or investigative journalism. On the contrary, all three are vital in a thriving democracy. Every newspaper worth its salt has opinions and makes them clear every day in their leader columns. If we don’t like them we don’t have to buy the paper.

Investigative journalists do more than express opinions. They suspect corruption or grotesque incompetence on the part of the authorities and they set about collecting the evidence to prove it. The history of journalism is replete with examples of courageous reporters who have exposed scandals and freed innocent people from prison or sent guilty people there. Many courageous editors have risked jail because they have taken a stand on something they believed needed to be exposed.

One of the most famous examples in recent years was the Daily Mail front page in 1997 accusing five young men of having murdered the black teenager Stephen Lawrence. Beneath the headline ‘Murderers’ and a picture of each man ran this line: ‘The Mail accuses these men of killing. If we are wrong, let them sue us.’ They never did. The Mail has won much praise for its coverage of the Lawrence murder over the years and rightly so. If the editor, Paul Dacre, had been sued and his accusers had proved criminal libel he could have gone to jail.

Several years later, when the only story in town was Brexit, Dacre ran a headline that won him not praise but condemnation. It brought the wrath of half the nation down on his head. This time the pictures were of three judges, resplendent in robes and wigs, who had ruled that the government would need the consent of Parliament before it could enforce Article 50. Dacre did not approve. The headline ran: ‘Enemies of the People’. The Press Complaints Commission received more than a thousand complaints and many fully paid-up members of the Great and the Good demanded Dacre’s head. How dare he treat our great independent judiciary with such contempt? The answer is perfectly simple and it’s summed up in two words: free speech.

Democracy cannot survive, let alone thrive, without it. One of the Founding Fathers of the United States, Thomas Jefferson, wrote: ‘Were it left to me to decide whether we should have a government without newspapers, or newspapers without a government, I should not hesitate a moment to prefer the latter.’ A free press is essential to free speech and free speech must include the freedom to offend – and even to cause outrage. If Dacre had broken the law he should have been charged with doing so. If his readers were outraged by what he had done they were free to stop buying his newspaper.

But the BBC does not enjoy the same freedom as a newspaper. Nor should it. It has a unique status as our national, not state, broadcaster: unique privileges and unique obligations. It has a guaranteed income. If you don’t pay the licence fee you can go to jail. It operates under a royal charter which guarantees its independence. But implicit in that guarantee is that its journalists are required to be impartial.

When everything else is stripped away the overriding duty of the BBC is to enable democratic debate. If we fail to do that we should be stripped of our licence to broadcast and someone else should be given the job. And any BBC journalist who allows his ego to override it should be slung out pronto.

Had Jonathan Aitken been able to prove that I was partisan – specifically that I was in league with the Labour Party – that would have ended my career as a news presenter at the BBC. And quite right too. Let’s be clear about this. I have views about pretty much every subject under the sun. I know the best way to cook chips and the worst way to peel an orange and the best way to run the country. Or at least I think I do. Don’t we all? In my years at the BBC I was happy to disclose the first two but not the third.

Many years ago, when he was a promising backbencher, Tony Blair told me I should give up journalism and become a barrister. Put aside the obvious flaw in the theory (I’d never pass the exams) he was right in one respect. There is a clear link between a barrister entering a courtroom to defend his client whom he strongly suspects is as guilty as hell and a presenter entering the studio who firmly believes the politician he is about to interview is a knave and a charlatan with policies that would probably bankrupt the nation in ten seconds flat if he had his way. The link is this: both barrister and presenter leave their views at the door of the courtroom or the studio.

I mentioned that one of my oldest and closest friends is Patrick Holden, an organic farmer and one of the tiny group of men and women who helped bring about the organic revolution which I believe has done so much to improve the way we farm in this country. Patrick has always complained to me that he gets a rougher ride if he is being interviewed by me on Today than if he’s facing any of the other presenters. It probably helps that, as a former dairy farmer, I’m reasonably well informed about the subject. But what really drove me was my concern to avoid any accusation of failing to be impartial.

I am acting as a devil’s advocate – and so should we all. I suppose if all that makes me sound too much of a goody two-shoes I’ll admit that there is another factor. I love arguing – and I don’t necessarily mean the sort of arguments I imagine eminent dons engaging in when they are sitting at their high table in one of our great universities after a few glasses of decent claret. I mean just arguing. It really doesn’t much matter what the subject is. My mother used to say ‘John could argue with the Virgin Mary herself’ and she was probably right.

Had Aitken succeeded in proving that I had betrayed that trust I would have been forced to resign. In fact, the bar for him to clear was set even lower. All he had to do was convince his ministerial colleagues – especially those in the Cabinet – that his attack was warranted. So the weekend of that phone call from Steve Mitchell was probably the scariest of my career. I knew – and, more importantly, so did Steve – that if Aitken’s colleagues shared his views and refused to be interviewed by me or even threatened to boycott the programme, I was toast.

The Saturday newspapers went big on the story. This, remember, was the era before social media and the BBC relied almost entirely on the verdict delivered by the papers. Some were broadly sympathetic to me, some were inclined to believe Aitken. Some never miss a chance to take a pop at the BBC, which they believe is too big for its boots and too often intrudes onto their territory. It was much the same for the Sunday newspapers. But everyone was waiting to see what would happen on Monday when the Today programme was back on the air. How would the top Tories, Aitken’s colleagues and friends, react?

I feared the worst. They might well see this as a chance to boot me up the backside. All it would take was a couple of the most respected colleagues to side with Aitken. I spent much of that Sunday discussing with my family how our lives would change if the BBC chose to bid me farewell. I seem to remember my youngest child volunteering that if we found ourselves on the streets having to beg for scraps she would leave school and take a job freelancing on a film set – preferably somewhere like Hollywood. Selfless to a fault.

It was late on Sunday night that the call came. It was the overnight editor on Today who took it and the caller was Douglas Hurd. Mr Hurd was the Foreign Secretary, one of the most respected politicians in Westminster. He had been booked to appear on the programme before the Aitken storm broke. He made no reference to Aitken but he had called, he said, to confirm that he would indeed be turning up for the scheduled interview. Oh and by the way, he added, ‘If Mr Humphrys is on duty, naturally I’d be happy to have him interviewing me.’

Normally we don’t give politicians any say over who interviews them but this was different. The threat may not have quite vanished, but the storm clouds had at least parted. Twelve hours later they vanished. Ken Clarke was on The World at One doing an interview about some economic matter and was, obviously, asked what he thought of Aitken’s comments. A lot of nonsense, he said. And that was all it took.

A few days later Ken came in to be interviewed by me on Today. I met him in the green room beforehand and handed him a calculator.

‘What the hell is this for?’ he asked.

‘Well,’ I said, ‘I thought it would help you keep track of the number of times I interrupt you and if I exceed thirty-two you can shout “Bingo!” or something.’

Ken looked at the calculator.

‘D’you know something? I’ve never really figured out how to make one of these things work!’

He was, as I say, Her Majesty’s Chancellor of the Exchequer at the time. I think he was joking.

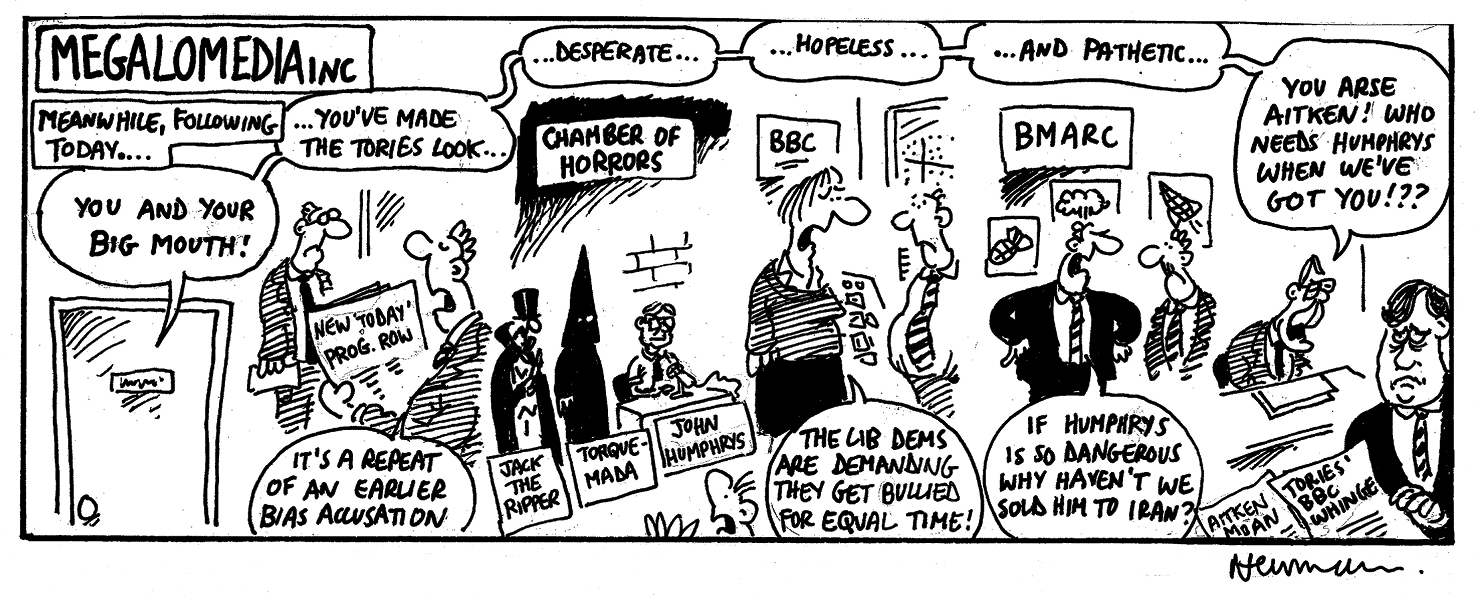

(Nick Newman)

There is a postscript to the Aitken story and I shall do my best to tell it without displaying obvious pleasure. Schadenfreude is, after all, not an attractive trait whatever the temptation. Four years after his attack on me Jonathan Aitken was no longer enjoying his life of privilege. He was in jail: sentenced to eighteen months for perverting the course of justice and perjury. Nothing to do with me, I hasten to add. Aitken had announced that he intended to sue the Guardian and Granada Television for defamation because they had accused him of taking bribes from Saudi Arabia. Just as he did when he had attacked me, he made the announcement with a great rhetorical flourish: ‘If it falls to me to start a fight to cut out the cancer of bent and twisted journalism in our country with the simple sword of truth and the trusty shield of British fair play, so be it. I am ready for the fight. The fight against falsehood and those who peddle it. My fight begins today. Thank you and good afternoon.’

That fight ended in a courtroom and a devastating defeat for Mr Aitken. The court chose to believe ‘those who peddle falsehood’ and he ended up serving seven months at Her Majesty’s pleasure. When he came out I asked him if he would appear on my On the Ropes programme. To my great surprise he agreed and to my even greater surprise he turned out to be a changed man: modest, repentant, all traces of the old arrogance gone. He had discovered God in prison and he ended up being ordained in the Church of England. He said at the time he did not want to become a vicar because he ‘wouldn’t want to give dog collars a bad name’ but he changed his mind and has since been ordained as a deacon with the intention of becoming an (unpaid) prison chaplain. As for me, I lived to fight another day.