18

Goodbye to all that

Writing this book has been a strange experience. It’s not that I’m new to the game. I have written seven books before this one, millions of words for newspapers and magazines, and more BBC programmes than I can shake a stick at. But this is the first time in half a century that I have written a single sentence for publication in one form or another without the tiniest fear, somewhere in the back of my mind, that the BBC might not approve.

The rules are perfectly clear. If you are employed by the BBC as a journalist you have to submit to a higher authority everything you write for publication. Fair enough. If there were no rules we could cheerfully take the BBC shilling and earn a few more by expressing our own opinions on whatever subject we chose and if that meant stepping over the line between analysis and opinion … so be it. After the Hutton crisis we news presenters were banned from writing regular newspaper columns on current issues full stop. For nearly five years I’d had a weekly column in the Sunday Times but that came to an end after Hutton. We all moaned about it of course and some subversive souls tried to get around the ban but I suspect most of us could see that the BBC might have had a point.

So it felt very strange embarking on this book knowing that I was free. I had finally taken the decision to retire from Today and would no longer be employed as a BBC journalist. No longer would I have to submit to the BBC Thought Police my subversive musings on everything from the nation’s favourite bird to whether all politicians are, indeed, liars. More to the point I would be free, for the first time since I signed on the dotted line in 1967, to tell anyone who might be interested what I really thought about the BBC:

- its failings and successes;

- its idiosyncrasies and its prejudices;

- its stultifying, jargon-ridden bureaucracy;

- its belief in the magical powers of the latest barmy management theory and the consultants peddling it;

- its persistent belief in the face of all evidence that every management email must contain at least one use of the word ‘exciting’ and another of the word ‘passionate’;

- its simultaneous delusions of grandeur and lack of confidence;

- its fear of its political masters;

- its even greater fear of the politically correct brigade and the most fashionable pressure groups – usually from the liberal left, the spiritual home of most bosses and staff.

There’s nothing we BBC worker bees enjoy more than telling each other how wonderful everything would be if only we were in charge of the hive. Maybe it’s like that in all large organisations. But there are a few things that make the BBC different, if not unique.

It’s a pretty basic rule of business that the bosses earn more than the workers. That’s not always so in the BBC and sometimes for perfectly good reasons. You would expect a star like Graham Norton to earn vastly more than his producer. The programme would not exist without him. There is only one Graham Norton and he IS the programme. You might expect star football players to get a decent fee for chatting about a match. Whether that justifies paying Gary Lineker £1.75 million a year is questionable at best. Some might say ludicrous. And to continue paying that amount only a matter of months after it was announced that people over the age of seventy-five who are not on pension credit would lose their free TV licences is verging on the suicidal.

And then we get to my own department. News. Presenters on the main news programmes make the editors look like paupers. At my peak I was paid more than four times as much as my editor. And that does not include all the extracurricular gigs: chairing conferences, making speeches, writing books and newspaper articles and so on that come with the job. True, the editors don’t have to get up at 3.30 in the morning but most were usually in the office soon after six and on call until late at night. Presenters finish at nine.

Then there’s the question of who gets the credit. If Today misses a big story – or misjudges it – the editor is blamed. If the programme is boring, ditto. If it lands a big interview or fixes what turns out to be a fascinating discussion the kudos almost always goes to the presenter. In simple terms, if something goes really well the presenters get to bask in the glory. If it goes badly the editors invariably carry the can.

You could argue that that’s inevitable. In the theatre the audiences rises to applaud the actors on stage who’ve been entertaining them for the last couple of hours rather than the director or backstage crew who’ve been working on the production for months or even years. It’s obvious why. The performance itself is all we see. It’s the same with Today.

You hear the presenter conducting a brilliant interview at 8.10, exposing the pompous minister for the devious chancer he is, demolishing his every point, reminding him that he’d said precisely the opposite only a few months ago, rubbishing his claims to prove his economic brilliance with unchallengeable statistics – and it is all done with that impressive calm and courtesy and modesty for which we presenters are so renowned. The plaudits should be ours and ours alone.

Or should they?

I wrote earlier that one of the iron laws of producing a programme like Today is that there is an inverse relationship between wanting an interview with someone – specifically with a politician – and actually getting it. The (unwritten) law states that the more we want to interview them, the less they want to be interviewed by us. Huge credit, therefore, to all the overworked and underpaid producers down the years who refused to take no for an answer when they were bidding for a tricky interview against the odds. The qualities needed are summed up in the ‘Three Ps’: persistence, pluck and sometimes even a dash of perjury. It takes a brave soul to phone the minister at home at 5 a.m. knowing that he has a reputation for eating young producers alive and also has the director general’s personal number on his speed dial.

Their reward for succeeding is pretty modest: promotion to senior producer. That means they will be entrusted to work all night with just one producer and then, when they are utterly knackered at six in the morning, have to spend three hours in a live studio doing one of the most high-pressured jobs in the business: putting Today on the air. In my closing months on Today I asked some of my colleagues (about thirty-two years too late) for their thoughts on the best things and the worst things about being the night editor on Today. The best things first, in their own words:

- Those nights when there is some big story – a big political resignation, a massive human-interest story, maybe Mandela dying – and Today gets everybody we bid for … exclusively.

- When the presenters come in and look at your running order and realise it’s going to be a brilliant programme … so good they can’t find anything to moan about although they’ll have a bloody good try.

- The morning when a massive story has broken overnight because a Cabinet minister at the heart of the Brexit negotiations has resigned at midnight and the first thing the presenter says when he walks in is something like: ‘So who’ve we got to talk about the resignation then?’ and you say ‘Actually nobody …’ and he snaps ‘Pathetic!’ and you say ‘… because we’ve got the minister himself!’

- The nights when you feel you’re at the centre of the world. You know half the country’s going to be listening in the morning to find out who won the election or the referendum or who’ll be the next president of the United States.

- It’s probably the same thing that keeps us all at the programme – the feeling (or fear) that we’ll never do anything that matters as much.

And these were some of the worst:

- Utter exhaustion … compounded by anxiety and stress … partners probably bear the brunt of this.

- That pit-of-the-stomach moment in the handover meeting when you realise the day team have had a nightmare day and you have four lead slots to fill, everything else is crap too, and you just want the day editor to hurry up and stop talking while you get on and try to repair the mess.

- The cringing embarrassment of having to tell the poor guest who has schlepped their way into the studio on a freezing morning and told his family he’s going to be on the Today programme that the news has changed in the last half an hour and he won’t be.

- Political parties being unreasonable … rarely in an Alastair Campbell shouty way but just lower-level resistance/obstruction.

And here’s how it was summed up brilliantly by one of our best night editors, Adam Cumiskey, who left Today a few years ago:

Those evenings when you arrive for work at 8 p.m. to discover that the day editor, who is well rested and has had a lot of resources to call on during the past twelve hours, hasn’t really bothered to put much of a programme together for you. The clock is ticking and you know you will have to rebuild the programme from the bottom up. You’re tired and have probably only had a couple of hours of broken sleep during the day. The way to fight this lethargy is to really shake the programme up or through a crazy amount of caffeine or calories. This means you really hit a wall at about 3 a.m. You start to doubt all your instincts, you become essentially a vessel where judgement and energy are pouring from your body. In those small hours you really start to doubt your gut feelings (in all ways). You feel your spirit and your body disintegrating. Then the presenters arrive with their own characters, strengths, insanity and weaknesses. This gives you a defibrillatory jump-start. You realise that you should be in bed asleep rather than face a savaging or at least a pretty rigorous test from someone who, unlike you, has just got out of bed after a decent night’s sleep and is raring to go. This is when you often find that your editorial judgement is going to be tested to the limit and if you’re lucky the craft of programme making and the osmosis of news absorption from the years you’ve been put through this will see you through.

By the time you get on air you’re flying, fuelled by an intense adrenaline-pumped desire to get over the three hours in the most creative way you can. If you’re lucky it works and you reach 9 a.m. relatively unscathed and with more positives than negatives. If not you head home for four hours sleep and try to do a better job the next day …

When I read that I felt seriously guilty. It should be compulsory reading for all wannabe night editors – except that it might put too many of them off – and definitely all presenters.

As for their bosses, the programme editors, it’s they who ultimately carry the can. They decide the tone, the texture and the content of the programme. Being the editor of Today is a bit like being the controller of Radio 4. It doesn’t matter what you do; there will always be someone, somewhere, who will accuse you of destroying their lives. By and large, regular listeners do not like change – which is both a blessing and a curse. It’s one of the reasons why Today has held on to its core audience for so many years. It has become a part of their lives. But when new editors come along they invariably want to make changes. They want to make their mark. And that’s not what many listeners want. Pity the poor editor who decides that maybe Today should give a little more coverage to the world of theatre, for instance. The cry goes out from the shires: ‘Dumbing down! I do not listen to a current-affairs programme to hear a bunch of luvvies prattling on. I listen to it for news and serious debate, dammit!’

Of the eight editors I have worked with I have had flaming rows with almost all and become good friends with most – often the same. I failed to have a flaming row with my last editor Sarah Sands, the only one who joined from outside the BBC, but not for want of trying. There are some people in this world with whom it’s impossible to have a real row and she’s one of them. She came in for a lot of stick when she joined the programme because her critics claimed she was one of those who loved luvvies and hated news. It was rubbish. It’s possible to be interested in both and she is.

Ceri Thomas served the longest and I mourned his departure. God knows how he survived so long given the hours he put in. I suspect it’s because he loved the job – especially preparing for big political interviews. We were sitting one morning in his little glass cubicle in Television Centre arguing about how best to hold Tony Blair’s feet to the fire and Ceri – usually a pretty undemonstrative sort of chap – gazed out across the newsroom and declared, almost reverently, ‘God! This is absolutely the best thing about this job!’

For some editors the worst part of the job was talking live into the presenter’s ear during the big interview. In my early years on the programme I tended to get a little heated. Too heated. I wanted to make my mark, to prove that I hadn’t got the job just because I’d been on the telly for the best part of twenty years. I wanted to show that I would take no nonsense from any politician trying to duck my question or answering a question I’d never asked – which was, of course, most of them at some time or another. So I did a lot of interrupting, even occasionally raising my voice a little. In other words I often went over the top and sometimes, to my great shame, lost my temper. That’s when the editor really should intervene and warn the presenter to back off. Some did, some didn’t. I rather wish I’d been warned off more often but I like to think that as the years went by I calmed down of my own volition.

Trying to gauge the temper of the audience is tricky. You know if you’ve gone seriously over the top because they tell you. But mostly they’re pretty tolerant and clearly there are an awful lot of listeners who want their political leaders to be hauled over the coals. So where should we strike the balance?

After presenting roughly 5,000 editions of Today I’m still not sure I know the answer to that. I’m not even sure that Today is doing the job it’s meant to be doing when it covers the political scene. That might sound disloyal but if it’s true I’d have to accept an awful lot of the blame. After all, I’ve been presenting it for about twice as long as anyone else. So let’s try to be a bit more specific.

It may be stating the bleed’n obvious but the first requirement for Today is that we have to tell the listener what is going on in the world. That is the sine qua non of all daily journalism. When dictators take over a country the first thing they do is occupy the radio and television stations and close down any newspaper that is not sympathetic to them – and there’s a very good reason for that. Controlling information is an essential step towards exercising power. As the Chinese are discovering, it’s much more difficult in a digital age, but even the ubiquitous social media has yet to reach the spread and influence of a trusted broadcaster like the BBC.

Next we have to put that news in context, to give the listener some perspective. That’s more difficult. For my money, the BBC massively overplayed the fire at Notre Dame Cathedral in April 2019. An important story, of course, and irresistible for television given the spectacular pictures. But not important enough to dominate the news for as long as it did. And definitely not ‘tragic’. Nobody died. Perhaps if the great cathedral had burned to the ground I’d have felt differently – but it didn’t and it is being restored. Many others will disagree with me. That’s inevitable.

News judgement is not an exact science. It’s a bit of an improvement on astrology or tarot cards but not much. We sometimes get it wrong – not least by overplaying London stories simply because that’s where most of us national hacks live. There’s an old journalist maxim that says all news is local: a thousand dead in a disaster in a remote part of China is equal in news value to the girl next door breaking a leg. It’s not too far from the truth.

In the pre-digital era we boasted that if you listened to us every day you did not need to read a newspaper. It was nonsense then and it’s nonsense now – if only because newspapers have opinions and Today does not. Nor should it. Newspapers can campaign and Today cannot. It can give a voice to campaigners but it must provide balance. There’s a difference.

A more credible boast would be that if you listen to Today you should know what’s happening in the world and be able to put it into some sort of context. Its job is not just to deliver the news, it is to explain why it matters and to provide analysis.

Politicians wield power and our job is to hold power to account. It’s not easy to do that if you get sucked into the political vortex. MPs thrive on the oxygen of Westminster. Many of them lose sight of the world outside. Indeed, the worst of them – a small minority I suspect – don’t much care about it. All that matters are the internecine battles and their next promotion. It is a world that provides endless material for journalists and writers of satirical novels and producers of TV dramas. It is seductive and thrilling. And it is mostly entirely irrelevant to the real world outside.

The danger for the Today programme and especially for its presenters is believing that just because a political story is thrilling for us, it is also exciting and relevant to the listener. The longer I’ve been presenting Today the more uneasy I have become about the relationship between us and them. At first it’s all rather exciting – especially if you’ve been a reporter on the road for as long as I was. In that job you have to try to find the people in power and then persuade them to talk to you. When you present Today they often come to you. It’s easy to believe that you’re more important than you really are.

Always at the heart of politics is the struggle for power: who has it and who might seize it from them. The real world is all about jobs and pay and schools and hospitals and rubbish collection and tax and knowing that your children are safe when they’re out on the street. But in the political ecosphere a spat between a couple of ministers might easily become the story of the day even if, as the old saying goes, they’re not even household names in their own household. Similarly an arcane argument over an obscure piece of parliamentary procedure assumes far greater importance than it deserves.

We make another mistake too. If there is a crisis in the school system or a shortage of GPs the first instinct is to talk to a politician for the big interview rather than a teacher or a doctor. The logic is that you’re more likely to get a ‘news line’ that way – even if it’s possible to predict pretty accurately what the minister will say long before they have even opened their mouths. But it’s faulty logic.

You might wonder why, if I’m right about this, I haven’t been making a fuss about it. God knows I’ve been there long enough. There are lots of reasons – none of them terribly convincing. One is that it’s fun interviewing politicians. Mostly anyway. Another is that it gets you talked about and, just like politicians, we hacks are not exactly averse to a bit of publicity. And the other may be that we, along with everyone else, have become victims – willing victims – of the age of celebrity.

In 1946 Winston Churchill made a joke about Clement Attlee, the man who defeated him after the war for the job of prime minister. ‘An empty taxi drove up to 10 Downing Street,’ said Churchill, ‘and Attlee got out.’

Not terribly funny perhaps, and anyway Attlee had the last laugh. He went on to become one of our truly great reforming prime ministers. But it worked at the time because Churchill had a point: Attlee was virtually unrecognisable to the general public. And he was perfectly happy with that. He neither sought nor relished celebrity. Is it possible even to imagine saying that of any modern politician who seeks high office?

Even serious programmes like Today are not immune to the curse of celebrity. It’s tempting to say especially programmes like Today. Too often we have behaved rather in the way a late-night celebrity chat show on one TV channel might compete with a chat show on another. Who’s got the biggest star for their show? Who can get their star to make the most outrageous comments about some other star? Whose star delivers the liveliest performances?

In some ways we might actually have been able to learn a thing or two from our light-entertainment colleagues. They’re probably much better than us at spotting when their audience has had more than enough of one topic or, indeed, of one ‘star’. In fairness, they have a much wider and deeper pool to fish in. Graham Norton is able to range across fifty or so years of film stars, pop singers, soap-opera actors and basically anybody who’s ever done anything remarkably clever or brave or unusual or just plain silly. They all really want to be on his show because they need the publicity and they’re being paid pretty well to do it. And, of course, this is their big chance to show the world how witty and entertaining they can be.

When there’s a big political story making the headlines and Today is casting around to fill the star slot the producers’ options are rather more limited. The big stories usually involve serious embarrassment in one form or another for the government, which means the producers’ first choice will almost certainly be a member of the Cabinet and most of them would rather drink a bottle of bleach than volunteer. Why run the risk of making a fool of yourself and damaging your own chances of one day becoming party leader – a dream most of them privately, if not publicly, nurture – when you can sit back and listen to one of your colleagues doing it instead? For ‘colleagues’ read ‘competitors’.

In other words, the poor old producer is having to ask them or their spin doctors to do something for which – unlike the chat-show guests – they won’t get paid and don’t want the publicity because they have roughly zero chance of making themselves more popular. Often the best they can hope for is to survive. And if that means winning the coveted Oscar For the Most Drearily Repetitive and Unrevealing Interview of the Year … that’s just fine. Indeed, for some it is the objective.

Not for nothing was the former Chancellor of the Exchequer Philip Hammond dubbed, with heavy irony, ‘Box Office Phil’. He was, in other words, a cautious chap who almost never gave away anything of news value. When I was new to the game I remember moaning to a politician after a particularly unforthcoming interview with him that there hadn’t been much point in doing it. His reply was along the lines of: ‘Sorry about that but I wasn’t doing the interview for you. I was doing it for me.’

So where Norton and his team will feed his guests agreed lines which they will seize on to deliver their pre-planned moments of spontaneous merriment, the Today presenter has the opposite role – and this is where I have become increasingly uneasy. As I suggested earlier in the book, the success of the 8.10 is too often judged on whether it has unsettled the politician and trapped them into saying something they had not intended to say, and not on whether it has succeeded in moving the debate forwards. Some would use a different verb for unsettle: ambush.

You may say: ‘Surely that’s your fault, Mr Humphrys. You’re the one asking the questions so why do it? And haven’t you come to this realisation a bit late?’

Guilty as charged m’lud, but let’s remember the New Testament says there will be more joy in heaven over the one sinner that repenteth than over the ninety-nine righteous men who need no repentance. And anyway, I’m not exactly at the sackcloth-and-ashes stage just yet. But I do wonder whether it’s time for a rethink. I’m not alone in that. Various BBC News bosses have been worried about it for years.

There’s usually a pretty clear correlation between how much they worry and where they come in the corporate pecking order. Relatively junior producers tend to cheer (albeit quietly) from the sidelines when a presenter seriously duffs up a senior politician. But the higher up the promotion ladder they climb, the more cautious they tend to be. The calculation is that it’s much smarter to be considered a safe pair of hands than someone prepared to take the occasional risk for a good story. Sadly, it’s not only the top bosses who take that view. Too many wannabe editors become increasingly cautious the closer they get to the editor’s chair. If there is such a thing as a corporate news culture it’s too often based on a philosophy of safety first.

One of the brilliant exceptions was Ceri Thomas. When he left Today he was promoted to a senior management job which, predictably, he hated. He was a serious journalist who wanted to keep being a journalist. So he opted to move down the management ladder (possibly the first in recorded BBC history to do so) and become the editor of Panorama. His big test came when he challenged a story to which BBC News (and most other national news organisations) had given enormous coverage. It was a truly terrifying story: a string of claims were made by a police informer known as ‘Nick’ that a wide group of the most powerful people in the land – from the former prime minister Ted Heath and the former Home Secretary Leon Brittan to the nation’s most distinguished military commanders – had been part of a paedophile ring. A senior police officer described the claims as credible and true. One of those claims was that they had organised the murder of some of their victims, including a young boy allegedly run down on his way to school.

Scotland Yard took the claims so seriously that they set up a full-scale inquiry under the code name Operation Midland. It was to cost £2.5 million. Far more importantly, it was to destroy the reputations and, in some cases, the lives of some of those accused. There was, though, a fundamental flaw with the claims. They were complete garbage from start to finish: the work of a fantasist named Carl Beech who is himself a convicted paedophile.

Ceri had his suspicions from the beginning. He was deeply disturbed by the BBC’s news coverage – the way the police accounts were accepted uncritically, its reliance on deeply flawed investigative work by a news website, and sympathetic interviews with ‘Nick’ – and ordered Panorama to find what he was convinced was the truth.

He was running an enormous risk. If he’d been wrong it might well have ended his career at the BBC. But he was right and the Panorama programme he and his team eventually delivered was a model of powerful, painstaking investigative journalism. In July 2019, five long years after Beech made his outrageous claims to Scotland Yard, he himself was convicted of twelve charges of perverting the course of justice and one count of fraud. He was sent to jail for eighteen years. By then Ceri Thomas had left the BBC.

When Evan Davis moved from Today in 2014 to take over Newsnight from Jeremy Paxman he criticised the combative interviewing style as ‘overdone’, ‘worn out’ and ‘not a particular public service’. He said a culture of broadcast journalists ‘getting the scalp’ and ‘tripping people into gaffes’ had created an ‘arms race’ between politicians and interviewers. And anyway, he suggested, it’s counterproductive: ‘Politicians get better defences as interviewers get better attack techniques. Politicians now sound defensive and boring instead of making gaffes.’

Evan acknowledged that ‘on a good day Paxman and Humphrys can do great interviews’. So far, so good. But then he added: ‘That style was fresh once and it has just become less interesting as everyone [has] seen it more and more used.’ Aggressive political interviews had helped create the ‘remarkable situation we are in … when you have a private conversation with a senior politician you come out more impressed than when you see them in public’.

Is that really ‘remarkable’? Aren’t private conversations always different from public conversations? Would we really expect politicians to say in public what they had just told us in private? I wish! It would make for some wonderful radio and the politician would be regarded as a hero. For about five minutes. Then his colleagues in Westminster would treat him as though he had a very nasty and very contagious disease and that would be the end of him.

In my early years on Today I remember being rather flattered if a politician was really candid with me in the privacy of the green room. He might agree enthusiastically that the government’s policy on dog walking was completely barking and the prime minister had only approved it because she had a visceral dislike of dogs. All very embarrassing for the PM if it were to be made public. But of course it would not be because the moment they’re in the studio and the green light comes on the ministers revert to type.

Embarrassing? Certainly not! The PM was showing her customary sound judgement and had taken a great deal of advice before reaching this wise position.

All these years later I’m still mildly disappointed when, say, a candidate for the leadership of his party tells me in the green room that the favourite for the job is a complete plonker, a proven liar and philanderer, who would lead the country to ruin and then, in the time it takes to walk into the studio undergoes some Damascene conversion. Would he serve in his Cabinet, I ask? Yes, of course he would, he assures me – without so much as the tiniest wink. But that’s politics for you.

Evan’s approach to politicians when he took over PM in 2018 was different from how I remember him when he joined Today in 2008 – at least in tone. He seems to have set out to be informal and friendly. His interviewees have become less like remote figures of authority who are there to be held to account and more like old mates who happen to have dropped by for a chat. He wanted to establish a different relationship with them – sometimes, in my view, rather bizarrely so. When the battle was raging for the leadership of the Tory party he invited the contenders to go for a stroll in the park with him and his much-loved dog Mr Whippy. Some accepted, some didn’t. I can see what he hoped to achieve: a way of breaking through the formality of the set-piece interview and establishing a more relaxed relationship. Maybe the politician would be less on his guard, less defensive, more likely to give us a glimpse of the real person behind the political mask. I thought it failed.

That wasn’t because Evan isn’t a good interviewer – on the contrary, he’s one of the best: clever, immensely well informed and genuinely curious – but because it was so artificial. We were invited to believe we were eavesdropping on a chat between two old friends but we were not. And anyway I don’t want the audience to think we presenters and the politicians we interview are best mates. Or even friends. Evan often uses their first names on air. I have always refused to do that and I wish they did not use ours. It was, I think, Paddy Ashdown who started it some thirty years ago. Sadly it spread. It gives the listener the wrong notion of our relationship. But it’s a losing battle.

Some of my former colleagues also think it’s OK to wine and dine politicians. Again I don’t. I can count on the fingers of one hand the politicians I’ve had lunch with (never dinner) and I stopped doing it completely some twenty years ago. It’s different for political correspondents who need to be on the inside, privy to the latest gossip and ideally ahead of the pack when a story breaks. The lunches are, of course, strictly off the record. That’s the whole point of them.

But presenters do not need to be insiders. On the contrary. When we want to know what’s going on we ask our immensely well-informed colleagues such as Laura Kuenssberg or Norman Smith. Our own relationship with the politicians is completely different. An off-the-record chat over a glass of decent wine might just possibly give you an edge in an interview but it probably won’t – precisely because it is off the record and you can’t refer to it. And anyway I’ve yet to meet the politician who will tell you stuff (strictly off the record old boy) that does not in some way advance his own cause. I suspect that politician has yet to be born.

Something else happened on PM after Evan arrived. He asked the listeners how they wanted political interviews to be carried out. And then he delivered what he called the Ten Commandments. Here’s a flavour (with my thoughts in italics afterwards):

- allow more space for the interview. Well … sometimes. But not always. It depends entirely on what is being said and how important the subject is. Sometimes the interviews aren’t too short: they’re too long.

- deconstruct what’s happening during an interview … for example pointing out when a question is not being answered. Obviously they should point out when questions are not being answered. I think mostly they do.

- achieve accountability through ‘enlightenment and revelation’ rather than head-on argument. Who could possibly argue against ‘enlightenment and revelation’? But sometimes you need a bit of an argument to get there.

- focus on big strategic questions, not just silly ones. Depends what you mean by strategic. Sometimes ‘silly’ questions can be revealing. If a politician doesn’t know the price of a pint of milk that might tell you quite a lot about him.

- make sure the goals are clear before we start. Of course … but what if the politician has a different goal and it turns out to be worth following up?

- inform the audience about contentious factual points. Again obvious – but often the ‘facts’ are contentious for a very good reason.

- interview important politicians on days when they are not in the news. Why? Why not interview teachers or doctors or scientists or plumbers or town planners or police officers or bankers or musicians or foster parents? I really dislike this one. Politicians get more than their share of airtime as it is. And if they are ‘important’ they will be interviewed.

- in discussions explore what the two sides agree on and not only where they disagree. Why?

- show more of our ‘working behind the scenes’ … explain what we’ve tried to do and who we’ve tried to speak to. Again why? If a politician refuses to speak to us we use the ‘empty chair’ technique – as Today did with Boris Johnson endlessly during the leadership contest. That mattered. But mostly it doesn’t – and I suspect the audience has more to worry about than the day-to-day problems of radio producers.

You’ll have spotted there are only nine commandments here. The tenth is a promise to review the project and listen to the listeners’ thoughts. As you will have divined by now, I’m not overly impressed by these commandments – but my real problem is with the underlying principle. I’m not sure why interviewers should expect the audience to tell them how to do their job. Perhaps that sounds arrogant but it’s not meant to be. I’ve always read all my letters and emails and, believe me, there have been an awful lot of them. Often they’re simply bonkers but, more often, they’re thoughtful and I take them seriously. Inevitably there is a huge range of opinions. Two people will listen to the same interview and one will think it was tough but fair and I should be congratulated while the other will think it was a ruthless, self-serving stitch-up and I should be sacked forthwith. So who’s right?

The problem is, there is no right or wrong way to do an interview. If you book a plumber to install your boiler you would not expect him to seek your opinion. He’s an expert. Interviewers are not. Almost all of us are generalists and interviewing is not a discipline: it’s an acquired skill. You can’t be ‘trained’ to do it. We all learn on the job. When ‘ordinary’ listeners get a chance to fire questions at politicians they almost always do a pretty good job of it. Maybe they’d struggle a bit to do a decent 8.10 interview but they might very well get the hang of it with enough practice. There’s a very good reason why journalism should not be described as a profession or even a trade. It’s because it’s not. You don’t have to be qualified – just competent. If I do a rubbish interview you might switch off, but it’s hardly likely to ruin your day. If the plumber gets it wrong and the boiler blows up it probably would.

Let’s be clear: I am not saying I believe we’ve got it right and anyway it really doesn’t matter. We haven’t and it matters a lot. In my own case I could probably count on the fingers of both hands the number of times I have ended an interview patting myself on the back. And the more important the interview, the less likely I am to have been satisfied with the way I’ve handled it. What I am saying is that the BBC cannot hand the problem over to the listener. The so-called ‘Open Politics’ approach of suggesting to them ten commandments seems to me at best a bit of a gimmick and at worst an abdication of responsibility. This is our problem – not the listeners’.

When the BBC’s late, great political editor John Cole retired he reflected that he ‘did find himself from time to time irritated by the fact that aggression in some cases has taken over from the desire to elicit information and … to force the interviewee to face up to any contradictions there may be in his position or any apparent weaknesses’.

So what should we be trying to do on Today? What we’re really after most of the time is that accursed ‘news line’. Something that might get picked up in the day’s news cycle and the next day’s papers with a credit for the programme. Ideally something that the poor bloody victim might live to regret when the party’s director of communications grabs them by the collar as they come out of the studio. They know that their job is to sound plausible and coherent and, above all, stick to the party line even if it requires them to argue that black is white. Especially when it requires them to argue that black is white.

John Birt may have been a bit unworldly but it’s hard to argue with his central criticism: too many interviewers (present company included) are too often more concerned with making headlines than with helping the audience understand the issues at stake. Obviously those aims are not mutually exclusive, but no interviewer ever got a bollocking for making headlines in the next day’s paper.

One of the most famous television encounters was between Jeremy Paxman and the former Home Secretary, Michael Howard, when he was running for the Tory leadership in May 1997. Everyone knows that he posed the same question twelve times without a satisfactory answer (actually, the numbers people put on it vary, but everyone remembers it). The BBC’s own history website tells us: ‘The refrain of “Did you threaten to overrule him” subsequently came to denote a high-water mark in the style of persistent, robust, but cordial interviewing technique pioneered by Robin Day and others forty year earlier.’

The problem is that most people can’t remember for the life of them what the interview was about. (It was about the details of a meeting between Howard and the head of the Prison Service, Derek Lewis, regarding the dismissal of the governor of Parkhurst Prison, John Marriott.) All that’s remembered is that Howard could not answer the question and resorted to increasingly desperate lawyerly formulations to avoid giving a direct answer. Some years later he reflected on the interview: ‘I’d been campaigning all day, I hadn’t remotely been thinking about Derek Lewis or prisons, I’d been thinking about the Tory leadership … This is not an excuse but perhaps an explanation, the end of a long day when you’re tired … I wasn’t able to go back over the history and so I answered in my own way. But I mean the questioning was slightly absurd because what I was not supposed to do [in office] was to overrule Derek Lewis and I didn’t overrule Derek Lewis and no one has ever suggested that I did.’ It’s quite possible that Howard had a point.

The former BBC director general Mark Thompson says political debate has become even fiercer because of the Internet. As he put it, words can hurtle through virtual space with infinitesimal delay and a politician can plant an idea in 10 million other minds before leaving the podium. The result is ‘a fight to the political death, a fight in which every linguistic weapon is fair game’.

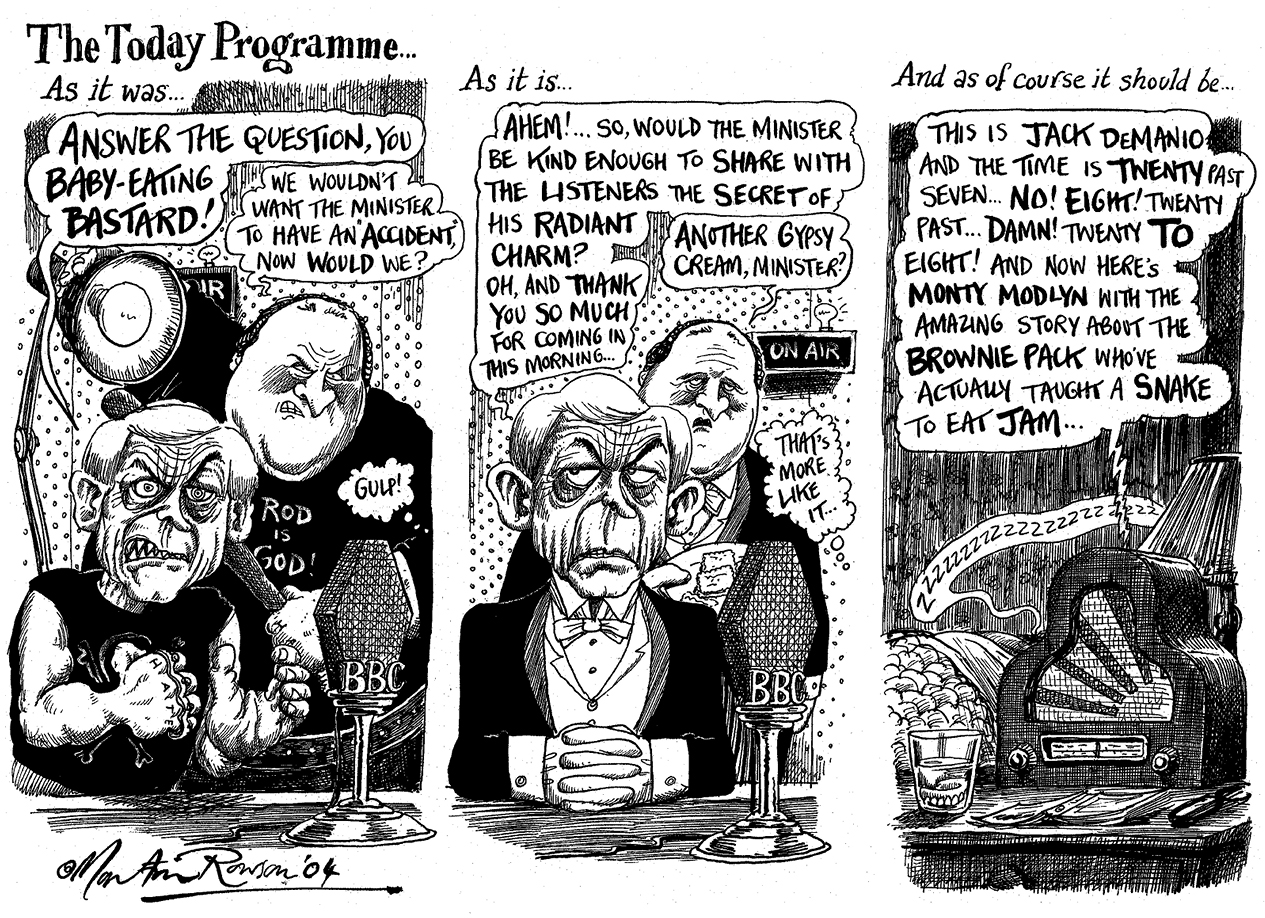

(Martin Rowson)

An interview on Today is not often a fight to the political death, but there can be a fair drop of blood spattered on the studio carpet at the end of some. If the politicians gave more straight answers to straight questions the interviews would be less confrontational but it takes two to tango. It’s not that there’s anything wrong with a bit of confrontation but without sharing Evan’s prescription I do have some sympathy for his analysis and I have come increasingly to believe that there may be some real downsides to the adversarial interview. It may add to the public’s growing unease with the political system.

When Tony Blair gave his farewell words as prime minister in the House of Commons in 2007, he said: ‘Some may belittle politics but we know it is where people stand tall. And although I know it has its many harsh contentions, it is still the arena which sets the heart beating fast. It may sometimes be a place of low skulduggery but it is more often a place for more noble causes.’

A politician’s gloss, you might say. But what if Blair is right? Let’s take Brexit, the greatest parliamentary crisis in my fifty years at the BBC. Certainly there has been plenty of ‘low skulduggery’. Many MPs twisted and turned to further their own selfish ambitions. Many more refused to compromise and stuck to their entrenched positions in the face of all the dire warnings of the terrible fate awaiting the nation. Skulduggery indeed.

But hold on a minute. Why do we almost routinely describe politicians’ ambitions as selfish but never our own? What exactly is wrong with relatively unknown junior ministers believing they are capable of holding the greatest elected office in the land? Perhaps they are – or at least some of them. Why should they be scorned because they don’t have the background we tend to associate with prime ministers?

We decry those politicians who soften their previously hardline stance and offer a compromise. And we decry those who stick rigidly to their guns. Politicians often do ‘stand tall’ – notwithstanding the Brexit debacle – and their beliefs are often firmly held. It’s at least possible to argue that the Brexit shambles happened precisely because so many MPs were driven by what they believe is in the interest of the country rather than their own base political advantage. Yet, by the very nature of the adversarial interview, we too often feed the preconception that they’re dodgy characters who are only in it for themselves.

The BBC’s founding father, John Reith, was evangelical about its role. It should ‘carry direct information on a hundred subjects to innumerable men and women who will after a short time be in a position to make up their own minds on many matters of vital moment’.

Obviously no BBC boss would get away with that sort of patriarchal, paternalistic approach today. The notion that without the BBC ‘innumerable’ men and women would be incapable of making up their own minds would be ridiculed, and rightly so. The boss would be out on his neck five minutes after he’d said it. But Reith’s ambition was laudable: the BBC should be a trusted deliverer of information.

Perhaps both sides, politicians and the media, are caught up in a contest neither can win. The politician ‘succeeds’ by clinging to the party line no matter how fed up the audience is with hearing it over and over again. At best it’s a draw. Or the interviewer succeeds by driving a wedge between politician and party line – in which case it’s entirely likely that the audience neither knows nor cares. And if we do manage to get a so-called news line? These days news can travel round the world and back at the click of a mouse. An interview on Today can be dissected and debated, diced and sliced, on a host of different platforms. Was this a slip of the tongue, or did we shine some light on a genuine issue? Commentators and experts can be wheeled in to give their view. More politicians opine. By the end of the day we may be no wiser. And then the process starts again with a different day and a different interview.

This has consequences for us all.

In his memoirs, Ken Clarke criticises the ‘hysterical 24/7 chatter that now dominates political debate’. Next week’s headlines, he argues, are given more priority by governments than serious policy development and the long-term consequences for the nation. ‘Media relations and public relations are now regarded as the key elements of governing,’ he says. It is, he concludes, a disastrous way to run the government of a complex modern nation state.

I wonder if there might be even more serious implications. Do we damage politicians by helping to lower their reputation in the esteem of the public? Do we fail to explain – or even try to explain – the complexity of the issues that they face? And if the answers to those questions are yes, then surely we create the conditions in which cynicism about politics and politicians can thrive.

Note I say cynicism and not scepticism. We should all be sceptical: it’s healthy. But cynicism is the enemy of democracy and the rise of populist movements and decline of mainstream parties across Europe seems to show that the gap between politicians and citizens is growing, not shrinking. Research suggests that ‘the government’ – regardless of the party in power – is perceived to make bad decisions. In the UK, government trust levels are lower than the global average. Young people tend to distrust the government more (only twenty-seven per cent trusted the government in 2018), and around ninety-three per cent feel that their views are not well presented by people in politics.

Have we unwittingly helped to create the conditions for this unhealthy state of affairs?

It was in the United States that the phrase ‘Beltway politics’ was first used to describe the disconnection between politicians and real people. Washington DC was inside the Beltway and it was there that politicians squabbled endlessly with each other, seemingly regardless of how ordinary people outside lived their ordinary lives. It was where lobbyists practised their dark arts, where Congress bowed its mighty head before even more powerful and infinitely more wealthy business leaders. The voters peered into this murky world from outside and did not like what they saw. One beneficiary of this disconnection, a few decades after the ‘Beltway’ phrase was born, was Donald Trump.

Trump’s opponent in the closing stages of the 2016 campaign was Hillary Clinton, but what he was really running against was what Clinton personified: the political system. He was the outsider and she was the quintessential insider. By every conventional measure she was infinitely better qualified than Trump – but he had a weapon that no previous presidential challenger had been able to command in the same way: social media. Trump had a direct line to the American people – or, at least, enough of them to get him into the White House.

In this country we may not have Beltway politics in quite the same sense – if only because the lobbyists and the wealthy donors have less influence – but the disconnection between people and politicians is growing here too. And social media is playing its part. This is why the role of the BBC has never been more important.

The Twitter image is seductive: birds tweeting away gaily to each other and simultaneously bringing joy to the hearts of those who listen. The reality has proved altogether darker. What was sold as the greatest aid to communication since Gutenberg, enabling the voices of ordinary citizens to be heard, has offered the mob something it had never had before: a guarantee that its often malevolent voice will be heard not just within its own circle but way beyond. The idea that an MP going about her job should be threatened with rape because she believes in something different from her moronic political opponent is not just a threat to her but to the very concept of democracy.

The notion of fake news might be mildly amusing when its claims are obviously bonkers. It might sometimes even harm the cause of those who spread the stuff. Trump’s boast about the size of the crowd at his presidential inauguration was an example of that. He claimed it was the biggest there had ever been and his staff continued to insist it was true even after every network in the States produced the pictures that showed it was rubbish. That might help persuade those who are open to persuasion, but not the tens of millions who believe the so-called mainstream media is a hostile force lying endlessly to protect their own privileged status. That’s when we should get worried.

In Britain there are some worrying signs too – albeit on a different scale. Members of both main Westminster parties – those who have not given up in despair – seem disillusioned with their leadership as never before. As Professor John Gray of the London School of Economics has put it, we are witnessing an unprecedented meltdown in British politics. The working class feel alienated because they believe no one is listening to them any longer and those people who voted to leave the EU feel betrayed. The danger is obvious – and we see it in pretty stark terms in one European country after another. As Gray puts it, when the main parties cannot give the voters what they want they turn to the extremes to vent their anger.

I voiced my concerns earlier about the BBC engaging in social engineering. It is none of the BBC’s business how society interprets the rules by which it chooses to live – still less should it bow to pressure groups who might want to change those rules. Cultural change is a continuing process and it’s the BBC’s job to report it – not to influence it. But the way in which the nation conducts its political debate is very much the BBC’s business because it is an integral part of it.

It goes without saying that its first responsibility is to expose the fake-news peddlers for what they are. There’s really only one way to do that: build and retain trust. For all its weaknesses and failings, that is what the BBC has been doing for the best part of a century. And if that sounds absurdly simplistic … so be it. The key is always trying to separate fact from speculation and never pretending to be privy to some great truth denied to others.

The second bit – the analysis – is pretty straightforward too. It’s the job of seasoned journalists like Katya Adler or Mark Easton to tell us what those facts mean, to analyse their significance. Sometimes they’ll get it wrong but that’s because they are journalists, not prophets. The journalist who never gets it wrong has yet to be born.

The third bit is trickier. It’s the tone of the debate.

Every presenter who has ever faced a politician across the Today microphones has to decide what tone they are going to adopt. The temptation – sometimes irresistible – is to imagine oneself wearing the robes of an Old Bailey judge or at the very least the wig of a prosecuting barrister whose job is to prove the defendant guilty. I write from personal experience. I’ve done it more often than I care to remember. And I usually wish I hadn’t. If we treat the politician like a suspected felon, why shouldn’t the audience do the same? Is that what we want?

Yes, there will be times when a bit of tough cross-examination is called for: times when there is pretty clear evidence that the politician is deliberately trying to mislead the audience. It’s probably true that some of us (again I include myself) should have been more robust when we were questioning claims made in the referendum campaign by both sides – often diametrically opposite claims. By definition they could not both have been telling the truth and they deserved to be exposed more thoroughly than they often were. The problem with that, as I mentioned earlier, is that when they know they’re bang to rights they tend to stay well clear of the studio. It’s on those occasions I envy the judge. How wonderful to have the power to be able to subpoena the witness, let alone the accused.

And smart politicians (just like smart journalists) will use every trick in the book to dodge the nasty stuff. I had just one interview during the whole Brexit campaign with the star of the Leave camp: Boris Johnson. It happened to come on the morning when the nation was getting very exercised about the claim writ large on the side of their campaign bus that if we left the EU we would have £350 million more to spend on the NHS every week. It was nonsense and of course Mr Johnson knew it was nonsense, but I never got the chance to challenge him properly. He was on a dodgy line from the West Country and every time I tried pressing him he would affect not to be able to hear me – so the interview got nowhere. It’s strange how often politicians suffer from temporary hearing loss or unexplained technical problems when the going gets really tough.

Yet the politicians are not often on trial for some heinous crime and if we interviewers treat them as though they are, it’s reasonable that the audience will do the same – or at least a sizeable chunk of the audience will. And therein lies the problem. Trust breeds trust and the opposite is true. Maybe we should allow the politician to do a bit more explaining and spend a bit less time forcing them to protest their innocence.

A former Newsnight editor once argued that a new contract needed to be drawn up between broadcasters and politicians to allow for a more open and informative format. He called interviews with frontbenchers ‘an arid, ritualised affair’. Twenty years after John Birt’s speech about political interviewing, we’re still talking about the problem without reaching any conclusion.

So am I repenting of half a lifetime spent interviewing politicians in the guise of devil’s advocate?

Not entirely.

Party politics is, by definition, based on opposition – albeit a little less robust than it used to be. In the House of Commons, there are two red lines running along the length of the Chamber between the two sides and it’s said that these lines are two swords’ lengths apart to prevent MPs duelling. Now they rely on verbal duelling, debating skills and occasionally a bit of rather childish name-calling.

In the model interview we test the argument, spot the flaws, challenge sloppy thinking and specious claims. We also aim to give the listener some pointers to the politician’s character. Can they be trusted or do they sound devious? Are they willing to engage in serious debate or just trying to pull a fast one?

Programmes like Today and Newsnight are fundamentally different from twenty-four-hour news channels or the TV and radio bulletins. Politicians know that their key message will be contained in a twenty-second sound bite and they will need to say the same thing to half a dozen different outlets to be sure of getting the message across. On longer programmes the interviewer must get behind the obvious message, give the audience a deeper understanding of the issue at hand, and help them reach an informed judgement. But how effective are we? Do we provide a proper alternative to the hamster wheel of news-channel coverage, where journalists run very fast in order sometimes to stand still?

Increasingly, I have my doubts.

When I joined the Today programme in 1987 none of these thoughts even entered my mind. I wanted to make a reputation for myself. I wanted to prove that I was at least as tough as any of my predecessors as well as becoming the conscience of the nation. Preposterous, I know, but it was a long time ago and I was very naive. After I’d been presenting the programme for about ten years I had lunch with a politician who’d spent half his life in Parliament and had decided he had had enough. I asked him how he thought interviewing had changed during those years.

‘I can’t really complain,’ he told me, ‘but I remember a time when we politicians were given the opportunity to think aloud. We can’t risk that any longer. We’d be taken apart. That’s a pity.’

He was right. In my decades on Today I struggle to recall a single interview with a senior politician, let alone a prime minister, in which they said something along the lines of: ‘Hmm … the opposition may be right about that … perhaps we should take it on board.’

Nor can I remember when I have said the equivalent of: ‘Ah … fair point … I was probably exaggerating when I said …’

So let me try to sum up my concerns after thirty-three years of political interviewing. It’s true that the news climate has changed and the relentless twenty-four-hour news cycle, combined with the incessant and often witless babbling on social media, militate against thoughtful debate. But even allowing for that Today presenters and their stablemates do have questions to ask themselves. Does an interview always have to be so combative? Does there have to be a winner or a loser? Does it have to be a zero-sum game?

If it does, the loser might very well be the public. If we interviewers succeed – albeit unintentionally – in convincing the listener that all politicians are liars, the real loser is our system of representative democracy that has served the nation so well for so long.

But perhaps I am too gloomy. Maybe that’s what sixty years in journalism does to you. Reporters are strange creatures. We are accused of endlessly searching for human frailty so that we may expose it – and sometimes succeeding. We deny the charge that we are interested only in bad news. Don’t we give endless coverage, say, to the arrival of a royal baby or a royal marriage? Indeed we do, often to the point of brain-numbing tedium. But we give more to a royal divorce. Yes, we seek out the bad news. Of course we do. We are more interested in the single plane that crashed rather than the thousand that landed safely.

We need to be where bad things are happening and, like most old hacks, I have had my share of them. I have seen an American president driven in disgrace from office, countries devastated by earthquakes or ravaged by war or brought low by famine. There is nothing more soul-destroying to report on than famine. It is perhaps the greatest evil of all because it strikes first at children. What remains most vivid in my mind, though – and I make no apology for returning to them – are the children of Aberfan. They were victims of a great crime: the exercise of power without responsibility.

But I have seen the other side too: the triumph of courage and compassion when disaster strikes. The sheer decency of countless people who sacrifice their own safety and even their own lives to help others. The sense of duty shown by many politicians who could earn far more money and lead easier lives outside politics, but genuinely want to help make their country a better place.

On the most personal level, I owe a huge debt of gratitude to the BBC. Flawed it may be – just as all of us who have worked for it or run it are flawed in our own ways – but I have not a shred of doubt that this country is richer for its existence.

And it could not exist but for the loyalty of so many millions. It’s true that we have tested that loyalty to breaking point more than once and it faces competition today the like of which it has never experienced since its first television broadcast in 1936. But I remain convinced that it occupies a special place in the nation’s heart and we would be the poorer without it.

When I joined the Today programme I wondered how long its great audience would tolerate me. It turned out to be much longer than I expected. I am in their debt too.

But after thirty-three years on Today I can’t deny that I’m rather looking forward to tomorrow.