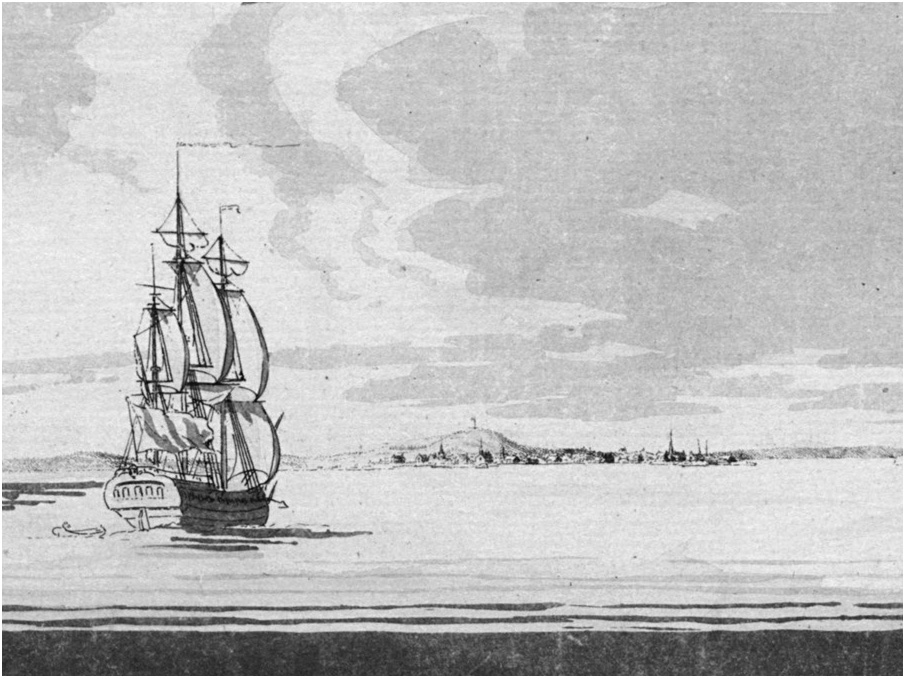

A view of Boston from the sea reinforces its connection to Britain’s overseas empire.

The sun was rising through a fair blue sky in late September as the flotilla got underway. More than a dozen ships, ranging from the forty-gun Launceston to unarmed sloops, carried over a thousand men and hundreds of women and children toward Boston. The journey took more than a week, and it would have been a relief to everyone to tack past the lighthouse that marked the beginning of outer Boston Harbor, even if they were still four or five miles away from Boston itself. From the ship rail, all that Matthew Chambers would have seen in the distance was a handful of church spires on a hilly landscape.

The next day, a Thursday, the flotilla sailed as far as the final pair of islands guarding the entrance to Boston Harbor. At noon, each ship dropped a single anchor in front of the flagpole of Castle William, the large square fort on Castle Island. Chambers and other soldiers of the Twenty-Ninth Regiment must have regarded the fort with curiosity. The stone barracks looked far sturdier than the rotten wooden structures they had endured in Halifax. There, the damp had rotted away most of their bedding, and for over a year Lieutenant Colonel Maurice Carr refused to order replacements, theorizing that they would simply rot again. It was not long before some of the men chose to make their beds out of leaves.

A view of Boston from the sea reinforces its connection to Britain’s overseas empire.

By contrast, the Castle Island barracks had been renovated a decade earlier, when the Massachusetts legislature, in the early days of the Seven Years’ War, allocated nearly a thousand pounds to upgrade and winterize them. Chambers might have heard the rumor that General Gage himself had ordered the Twenty-Ninth to stay in these snug barracks. Lieutenant Colonel Dalrymple, now in charge of all the troops en route to Boston, had received the order in a letter from Gage, his commander, before they had sailed.

But as the soldiers waited on the ships all afternoon, they saw no dinghies coming alongside to bring troops to shore. The next morning Dalrymple and James Smith, the captain of the flotilla, hurried up the path to the fort. The lieutenant colonel expected a frustrating argument about where to quarter the troops and who would foot the bill; the Massachusetts governor had alerted him that agreement on these issues would not be simple, but Dalrymple hoped that a little diplomacy could smooth over the matter.

In the council chamber of Castle William, Dalrymple found the governor and his council. The latter consisted of ten men, all elected by the Massachusetts legislature and given control of the purse strings of the province of Massachusetts. They had the power to allocate the space and the funds for quartering troops. Recalling his previous two social visits to Boston, Dalrymple tried to win over his audience with warmth. He “hoped he was going among Friends,” he began, and assured the council members that he wanted everything to proceed as smoothly as possible. Gage had ordered him to establish one regiment at Castle William and the other in the town. Boston’s officials would not, he was sure, want to impede these orders, and if they would simply authorize access to spaces he might use for barracks in central Boston, the troops could begin to unload. Dal

The council refused to be swayed by Dalrymple’s gentle approach. They gave him the same answer they had earlier given the governor: they had no objection to putting the Twenty-Ninth Regiment in Castle William, but they would not countenance the quartering of any regiment in the heart of Boston.

The Governor’s Council had already consulted with the town’s selectmen (including John Rowe) on this matter, and they had both an explanation and a reason for the refusal to let the army quarter troops in town. The explanation was legal, but the reason was emotional: they were offended that the governor, the general, and the secretary of state himself considered Boston unruly and ungovernable, and they could view the order for a regiment to be housed in Boston only as a desire to punish the town. Governor Francis Bernard had defiantly admitted to the council that the troops were coming “in consequence of” the riots of the previous spring. The only reasons the ministry could have decided to order the troops to Boston, the council shot back, was if the governor and his friends—some “ill-minded persons”—were “disposed to bring misery and distress upon the town and province.”

In the context of this angry exchange, the council and selectmen sent the governor an official letter stating that both regiments should be housed in the refurbished Castle William barracks. The officials based their recommendation on the 1765 Quartering Act, which held that troops were first to be quartered in existing barracks; only when those were full could other troops then be quartered in inns and public houses, and only when those inns and public houses became full in turn could troops be quartered elsewhere. Inns and other buildings were, moreover, to be rented out of the Crown’s pocket, not the province’s. In other words, the army could not simply appropriate housing from the town of Boston, at least not without paying for it.

Bernard and Dalrymple were infuriated by this reading of the Quartering Act. What was the point of stationing a peacekeeping force “Seven Miles by Land and three by water” from the center of Boston, even if the barracks were technically within the limits of the township? Having troops so far from the town could not, Bernard stormed to Gage, fulfill “the purposes intended by sending troops to Boston.” But try as the two Crown officials might to come up with compromises and alternatives, the council refused to budge.

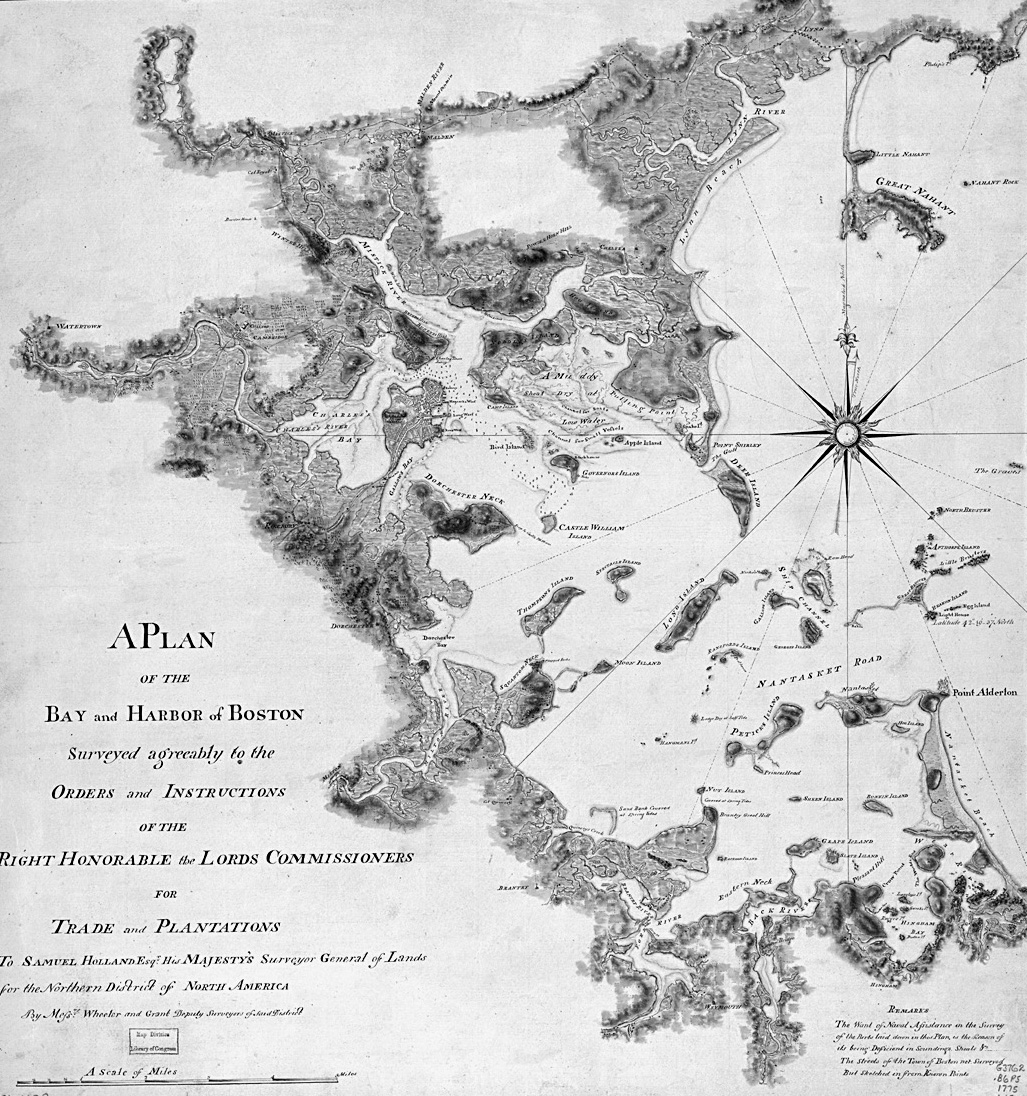

This chart illustrates the narrow channel available for ships to sail between Castle William and Boston’s Long Wharf.

Meanwhile, the regiments were stuck on the ships until Bernard and Dalrymple could resolve the dispute. Through the rest of Thursday and on into Friday morning, the ships remained anchored off Castle Island, until Dalrymple decided he had had enough. Far from following his original orders and putting one regiment in the barracks, he would put all the troops in Boston proper. He did not care if they had to camp out on Boston Common, among the town livestock, so long as those recalcitrant Bostonians understood that he was not to be trifled with. There was no point in lingering by Castle William; by ten o’clock that morning, the ships began to pull up anchor.

As the fleet traversed the three miles into Boston Harbor, the spires that Matthew Chambers had seen from Boston Light slowly came into view. They towered over a motley collection of some two thousand brick and wooden buildings. Despite the fog and drizzle, however, what stood out most was the Long Wharf: 1,586 feet of wooden planks and stone pilings stretching out to sea, lined on either side with warehouses and taverns and filled with pedestrians. Up to fifty ships could moor there at a time, bringing wares from around the world to the colony’s shops and storehouses. The Long Wharf embodied Boston’s affiliation with the British Empire, symbolically pointing east to London. When Captain Smith and Lieutenant Colonel Dalrymple ordered the fleet to set their moorings in a semicircle around the Long Wharf then, blocking it from the open sea, few Bostonians would have missed the point: it was meant, as Paul Revere noted, to look like a siege.

But Matthew Chambers was no Bostonian. As he gazed at the buildings ahead of him and the barracks behind him on Castle William, he must have wondered where his own family, once they finally disembarked, would sleep that night. The question was hardly an idle one, and the answer turned out to be far more significant than Matthew could have known. It was to change everything about Boston and its relationship with the British Empire.

It took several days and much work to disembark one thousand soldiers. From the ships moored out in the harbor, small groups of men were rowed on dinghies to the Long Wharf. To offset the tedium, Lieutenant Colonel Dalrymple decided on a grand display: at noon on Saturday he ordered the two elite companies from each regiment to disembark and march directly down the most prominent road in Boston. As these men from the Fourteenth and the Twenty-Ninth Regiments gathered on the eastern end of the Long Wharf, they unfurled their banners and fixed their bayonets to their muskets, an unmistakably martial gesture. The Fourteenth Regiment led the parade, marching up King Street, straight into the heart of Boston. Stopping at the east door of the Town-House and massing on the street in front of the Custom House, they waited until the Twenty-Ninth Regiment caught up. Then two hundred men marched together through the town center, their standards fluttering and the sound of fife and drum filling the air. They made, as the Bostonian John Tudor admitted, a “gallant appearance.”

Impressive as the parade may have been, it did nothing to solve the problem of housing. With nowhere else to go, the Twenty-Ninth Regiment pitched tents among the cattle that grazed on the Boston Common; the Fourteenth managed to get under a roof in Faneuil Hall; and a detachment from the Fifty-Ninth Regiment, sent from Halifax with the Twenty-Ninth and the Fourteenth Regiments to fill out their numbers, found shelter in an empty warehouse. Over the next few days, Matthew and the other men began to disembark and join their regiment. The four smaller transport ships, stuffed with baggage, women, and children, were still out on the Atlantic.

As the troops landed, they started to unpack the provisions and gear they had brought from Halifax. Matthew’s Twenty-Ninth Regiment had brought tents, which they liberally scattered over the Common. A watercolor painted that fall depicts the tents and troops in a rolling landscape, dominated at the back by the merchant John Hancock’s enormous house and the tall beacon tower of Beacon Street. Couples and families stroll through the Common; townspeople and troops are sharing this central pasture.

Even more centrally located were the Fourteenth Regiment’s temporary quarters in Faneuil Hall. The first floor of the building, rebuilt only five years earlier, was a public market, and the second floor provided meeting rooms for the town government, including the Boston Town Meeting and the smaller, elected Town Selectmen. Faneuil Hall was less than a five-minute walk from the Long Wharf, the Town-House (the home of the royal and the provincial governments), and King Street, the commercial, legal, and political heart of Boston.

This main street was dense with taverns, shops, and offices, including the Custom House and the Royal Exchange Tavern, a three-story building where merchants shared drinks and gossip. From here it was only a hundred yards to the beginning of the Long Wharf, where two more taverns served customers. At the Sign of the Ship, one of the two, the proprietor, Sarah Bean, also offered rooms for travelers looking to journey to the port of Salem on the stagecoach that stopped almost every day.

Next to the Custom House, a militia captain owned a tailor shop, and across the street Rebecca Payne sold customers the raisins, sherry, Jordan almonds, and delicate rose-colored silk fabrics that her husband, Edward, imported in his ships. From the very next house, Joshua Davis sold fresh lemons from Spain, and nearby were others selling cheese, coffee, and gloves. King Street even included a choice of wigmakers who catered to the fashion for powdered hair: Abraham Vernon across from the Custom House, Timothy Kelly across from the British Coffee House, and John Piemont farther down. The lieutenant governor bought his wigs from Piemont and retained him as his barber; so did other wealthy men, including the merchant and Son of Liberty John Hancock.

The whole range of Britain’s trade could be found on King Street and the Long Wharf. Henry Lloyd’s warehouse on the wharf displayed goods from all over the world: “French Indigo, Albany Peas, Connecticut Pork, Esopus Flour, new-York Butter-Bread, refin’d Iron, Pig Iron, Ship Bread, Cordage, Anchors, Spermaceti Candles, Cotton Wool, Silk Handkerchiefs, Feathers, Logwood, &c, &c.” The same warehouse put humans up for sale as well: “One New negro Boy, three Girls: also a negro Man, that has been in the Country some Time.” Just a few steps away, auctioneers sold people in the Royal Exchange Tavern, the Crown Coffee-House, and the Bunch-of-Grapes tavern. In summing up the power and the extent of the empire, King Street could not have been better named.

October in New England can be beautiful. On a fine Sunday two weeks after the troops had paraded down King Street, the sun sparkled on the shallow water of the Frog Pond, on the yellowing leaves drifting on the autumn breeze, and on the bright red of the Union Jack fluttering in the middle of the Boston Common. It illuminated the dull canvas of the army-issued tents grouped under that flag, a military encampment in plain sight of the townsfolk as they made their way to church that morning. Given this influx of more than a thousand new residents, Bostonians could not help but encounter military families at every turn: in the streets, in the churches, and eventually even in their own homes.

On that Sunday, the sun’s warmth may have seemed like a good omen to Jane Chambers as she rocked her sick baby in a tent on Boston Common. Meanwhile, her husband, Matthew, pleaded anxiously with the minister of a nearby Congregational church to agree to an emergency baptism for his dangerously ill baby girl. Matthew may have guessed that many Bostonians, some of them members of this very church, did not want soldiers like him in Boston. Why would they allow their minister to baptize the sick child of a British soldier? Moreover, as a rule, Congregational churches insisted that parents had to be members of a congregation before their child could be baptized.

This particular Congregational church seems like a strange choice indeed. The West Church had, in the 1760s, a minister who had been a fierce opponent of the Stamp Act, and the church continued to oppose the political positions of Crown officials. That such a church would be willing to vote its approval for the hurried baptism of a “Daughter of Mr. Matthew Chambers, a soldier of the 29th Regiment, who has, as he says, had children baptized in Ireland,” seems surprising. Yet in the midst of a fierce political battle over the abstract idea of “soldiery,” a minister and a worried father found common ground.

A week after the baptism of baby Jane Chambers, named for her mother, the three-year-old child of the Boston merchant Benjamin Goodwin disappeared one afternoon. The child was kidnapped from his school by a Boston woman who had been released from jail the week before. The town crier was sent around to announce the child’s disappearance. He began in the North End, where the boy was last seen. The child was eventually rescued at the edge of the Frog Pond on the Common, where the same Boston woman was stripping him of his clothes, pocketing the valuable metal buckles and buttons, and seemingly on the verge of drowning him. But it took the rest of the day for the news to reach the Goodwins. Late in the evening, the crier finally made it to the military encampment on the Common, where a soldier’s wife told him that she had a child in her tent, brought there by “a woman belonging to the town.” This wife had put the exhausted child to sleep until it could be “carried home to its Parents.”

The kidnapper was identified that night in North Square. A crowd surrounded her and dispersed only when the night watch arrived and brought her to the workhouse. There she stayed until morning, when a justice of the peace committed her for trial.

The newspapers reported this incident as the lurid tale of a depraved criminal who preyed on innocent local children. But this same tale also includes an unnamed soldier’s wife in a sympathetic role. The Boston Gazette reported that she took tender care of the little boy until he could be safely reunited with his mother. As the child traveled from the North End to Boston Common and back again, he wove a connection between two women based on their common care for a child. At this moment the divide between civilian and military did not matter.

Despite such moments of mutual understanding, the tensions created by the new military presence were real—and were only aggravated by Boston’s culture of heavy drinking. On the morning after the troops disembarked, John Rowe strolled from his house to the center of town, and on King Street he entered his usual club, the British Coffee House, to do a bit of business. He found the coffee rooms and the hallways full of army and navy officers, while the two enslaved servers dashed around, serving them coffee, Madeira, and rum. Here Rowe encountered Ralph Dundass, the captain of one of the schooners that had brought soldiers from Halifax. The two had met before.

To Rowe’s utter surprise, Captain Dundass spoke to him belligerently. “Hah John are you there Dammy I expected to have heard of your being hang’d before now for Damm you you deserve it.” Rowe tried to laugh off the threat, but Dundass insisted that he was not joking. The captain repeated that Rowe was a “damn incendiary” who should be “hanged in his shoes.” Although Dundass had not been in Boston since the previous year, when Rowe had spearheaded the merchants’ boycott in response to the Townshend Acts, news had clearly traveled fast. Rowe looked around for his friends, in case Dundass became any more hostile, but though he saw a few drinking in the doorway, none rushed to lend support. The Bostonian decided discretion was the better part of valor, and went home.

Some army officers seemed to make trouble each time they drank. In every neighborhood, the men who served as the official neighborhood watch complained throughout November that officers “in Licker” harassed them frequently. The verbal abuse was seldom intense enough to be taken seriously, but it was common. One night, after midnight, an officer stormed into the night watch’s little warming house near Dock Square, cursing “God dam you what do you think to do will you stand 4 regiments I will fetch them and set you all in fires in a menet and drive you all to hell and damnation.” When other officers came back to the watch house two days later, “hollowing swearing and making a noyse,” the constable threatened to lock them up until morning. At that point, the officers made extravagant apologies: “They asked pardon for what they had done and ofered to [go] down on the [k]nee.” The constable let them go home and sleep it off.

Before the end of October, an army officer named John Wilson made threats quite similar to those that Dundass had leveled at John Rowe. The Boston Evening-Post reported that while in a King Street coffee house, Wilson had “greatly insulted” two Bostonians by referring to the locals as “liberty boys, rebels, etc.” The incident made a big splash. The partisan news report known as the Journal of the Times, written anonymously by a group of liberty party supporters, suggested that the officer was not man enough to stand up to the Bostonians he insulted. Having shouted out “very indelicate threatenings,” Captain Wilson apparently began to fear that one of them would beat him with a cane. The paper mocked him for summoning the sheriff to escort him home. The Boston shopkeeper Harbottle Dorr annotated the newspaper account, jotting in the margin that the “Captain of the Regulars” in question was known as “Bully Wilson.”

Wilson’s hostility revealed a fundamental conflict between Bostonians and some imperial agents. A week after the episode at the coffee house, Wilson was publicly drunk again, and this time his outburst struck deeply at the racial fears of some Bostonians. It was, as Joshua Henshaw explained to his cousin in western Massachusetts, “an affair of a blacker complexion,” one that exposed a deep fault line within Boston’s political culture: slavery. Henshaw succinctly described the incident: “Capt. Willson one evening last week, coming from an house at the South End, where he had drunk plentifully, met with several Negroes in the street, asked them whether their masters were Liberty Boys, they made him different answers, he told them to go home, be abusive to their Masters, & to cut their throats, then to come to him for protection, he would give them arms, & make them Gentlemen soldiers.”

It was one thing for an officer to taunt another gentleman with charges of treason; it was something else entirely to incite a slave uprising. Was this a political move on Wilson’s part? Was he simply trying to stir up trouble? Slaveholding crossed political lines in Boston. Sons of Liberty as well as supporters of the Crown held people in bondage. Boston slave owners were more than indignant; some were frankly terrified.

A few of those slave owners happened to be in the street that night. Nathan Spear, Zachary Johonnot, and William Foster heard Wilson’s threat and rushed to complain to the selectmen. Town officials spent several days taking their depositions and then went into action. They started legal proceedings against Wilson. They also ordered the town constables to step up their surveillance of enslaved men, especially at night.

Wilson led the Boston sheriff on a chase around Boston for a full day; in the end, the captain hid in the warehouse barracks assigned to his regiment. Not until one of the justices of the peace threatened to raise a posse to help the sheriff arrest him did Wilson finally give himself up. A troop of constables led the captain first to the house of Justice Richard Dana and then to the selectmen’s office in Faneuil Hall, an unusually public site for a simple bond hearing. The size of the bond was unusual too: four hundred pounds. Dana and other officials wanted to teach Wilson a lesson.

Wilson tried to mollify the selectmen. He assured them that he had not really meant anything by his speech to the enslaved men. Henshaw wryly wrote to his cousin that “his excuse was as usual & as good as usual that he was drunk.” John Rowe, in his role as selectman, accepted the excuse, noting in his diary that the officer had been arrested for “some drunken behavior.”

Whether or not Wilson had simply allowed liquor to get the better of him, slave owners fretted over the implications of his threat. Would the army give enslaved Bostonians ideas? There were already nearly a dozen free black men in the Twenty-Ninth Regiment, serving as drummers; they received regular wages and the promise of a pension at the end of their service. It would not take much imagination on the part of an enslaved Bostonian to see the attraction of Wilson’s suggestion of freedom in the British army.

Even free black men in Boston did not have the same status as white civilians or black soldiers, especially when it came to patrolling other people. For most of the eighteenth century, black men were excluded from participating in either the militia or the watch. White legislators would not give them the authority to arrest other Bostonians or to carry arms. Instead, free black men were compelled to perform the civic duties of cleaning and paving public roads. Boston selectmen assessed each of them up to thirty days of unpaid work on the town’s highways per year. Unsurprisingly, the black men engaged in constant battles with the selectmen concerning the completion of such unpleasant and unremunerated work. Their civic service looked far more like slavery under an overseer than did the sociable, alcohol-fueled “training days” of the local militia.

Nor could white Bostonians feel confident in the stability of slavery. Massachusetts law allowed enslaved people to sue in the courts and receive due process. From the 1760s into the 1770s, enslaved men and women brought cases against whites for unlawful imprisonment, for back wages, and, occasionally, for their freedom. Although the suits themselves did not spell the end of slavery in Massachusetts, they certainly made clear its shaky foundations in both law and custom.

Henshaw scribbled a hasty note to his cousin at the bottom of his letter: “Quere: whether it will not be prudent to keep the affair of Willson with the Negroes as secret as possible.” What might happen if enslaved men like Cato Spear or Caesar Johonnot began to think that the British army might have the power to end their servitude? Would enslaved men and women, rather than wait for the British army to come to their aid, decide to take that power into their own hands?

Nathan Spear and Zachary Johonnot were right to be concerned about the precarious foundations of slavery in Massachusetts, and at some point amid the tumult of the following decade, both of them emancipated their slaves. But the “affair of Willson with the Negroes” made clear to everyone that even casual encounters between Bostonians and soldiers befuddled by drink touched on issues with enormous and long-reaching implications.

The army, the town, and the governor continued to argue over where to house the troops. Several officers had no intention of camping out in Faneuil Hall or the Town-House and had already obtained private leases for themselves. Less than a week after disembarking, two officers from the Fourteenth Regiment, Captain Brabazon O’Hara and Major Jonathan Furlong, rented houses on Essex Street from John Rowe, who charged them each the healthy sum of twenty British pounds per year.

The need for more permanent housing was felt not only by the men, women, and children of the Fourteenth and Twenty-Ninth Regiments. A detachment of the Fifty-Ninth, which had come along from Halifax, had to be quartered as well, as did the Sixty-Fourth, which arrived from Ireland soon after. It could have been worse: the Sixty-Fifth Regiment, traveling with the Sixty-Fourth, were housed in Castle William and so did not add to the press for housing in the town. But the current conditions in Boston could not be allowed to continue. Soldiers and families could live only so long among the livestock on the Common or on the crowded second floor of Faneuil Hall. This last place was particularly galling: the troops slept among the town’s stock of muskets and in doorways to the chambers used by the Boston Town Meeting, the Boston selectmen, and the court.

For the most part, neither town officials nor many Bostonians were willing to help. The troops attempted to take over one provincial building, the manufactory house, but the families living inside mounted a four-day standoff, rebuffing and humiliating the soldiers. General Gage himself came to Boston in mid-October to resolve the impasse, but his presence produced no immediate results. A few days after his arrival, the Boston minister Andrew Eliot wrote to a political supporter in Britain, “The present disposition of the people is to treat the troops with civility, but to provide nothing.” Understanding the town’s tactics, Bernard and Gage fumed that Bostonians seemed to think that they could force the troops to leave if soldiers had nowhere to live but the Common. Though the army would not in fact be forced out, its leaders were running out of housing options. Neither the governor nor the army officers could find a way to refute the town officials’ legal arguments.

Even the rental of warehouses and private homes was a financial challenge. To his great annoyance, Lieutenant Colonel Dalrymple found that the cost of these rentals would need to be borne not by the colony but by the army itself. Dalrymple justified the cost, however, especially in the rental of private homes, where soldiers and families could mingle with townspeople without supervision, by praising “the uncommonly good behavior of both officers & soldiers.”

In long, self-justifying letters to the Earl of Hillsborough, Governor Bernard explained why he could never compel Boston officials to offer free housing to the troops. At last, Bernard and Dalrymple managed to avoid the town’s political and legal challenges through the simple expedient of money. The army agreed to pay locals for the rental of private rooms, and the troops could finally move into more comfortable quarters. Historians have spilled a good deal of ink explaining the machinations of this compromise and noting, not without amusement, the speed with which moderates like John Rowe and hardcore liberty partisans like William Molineux compromised their principles for cash and rented their property to the army. But financial details and ideological ironies pale in importance compared to the profound social change created by the wide dispersal and mingling of troops with civilians throughout the town of Boston.

By the beginning of November, Gage’s officers had found thirteen buildings—storerooms, sugar houses (sugar refineries), even a cotton warehouse—to refashion as barracks. John Rowe rented the military one of his warehouses. William Molineux rented one of his own and acted as an agent for three others on Wheelwright’s Wharf. Dalrymple hoped that such buildings would keep soldiers in the heart of the town, yet isolate them from townspeople; his hopes were entirely unreasonable. As the drama over the kidnapping of Benjamin Goodwin’s son showed, even putting troops in a military encampment could not segregate them from civilians altogether. Moreover, thirteen buildings were not nearly enough to house all the troops. By the time the Sixty-Fourth and Sixty-Fifth Regiments arrived, in the middle of November, there were roughly 2,000 men, 380 women, and 500 children who needed a place to stay.

The army was not looking for particularly luxurious housing. A full-size barracks in Halifax was about 160 feet long and 32 feet wide; divided into twelve rooms, it was intended to house 336 soldiers. By contrast, a typical Boston sugar house was only about one-third the size. Even with fourteen privates per room—senior officers got their own rooms, subalterns had to share two to a room, and privates had to share four to a bed—dockside warehouses would be insufficient, and Boston simply did not have enough vacant sugar houses. In the end, the army also rented private houses, rooms in private houses, and even outbuildings to house the overflow. As a result, the troops and the townspeople found themselves living very close together. Matthew and Jane Chambers managed to lodge their family in South Boston, renting a house near the Orange Tree Inn.

No sooner had members of the army started to settle in than some of them wanted to leave. Officers, in particular, wanted to flee this particular assignment. Urban policing had no opportunities for glory, but many possibilities for failure. The secretary at war himself admitted that it was “a most Odious Service which nothing but Necessity can justify.” In the spring of 1768, as Secretary Barrington faced a major riot in London as well as mobs across England, he lamented, “Employing the Troops on so disagreeable a Service always gives me Pain; the present unhappy Riots make it necessary.” The commanding officers in Boston could not have agreed more. When General Mackay’s transport ship from Ireland was blown off course, and Mackay was forced to spend the winter in the West Indies, Colonel John Pomeroy of the Sixty-Fourth Regiment was given the temporary rank of brigadier general and the command of all the Boston troops (superseding Lieutenant Colonel Dalrymple). Pomeroy arrived in Boston in November and within four months was pleading with General Gage to allow him to return to England. When General Mackay finally arrived in Boston in the spring of 1769 and was forced to assume the top position, he lasted only six weeks before he began begging for a home leave. Other officers too applied for permission to escape; Mackay included four officers’ requests along with his own. Even Dalrymple immediately asked Mackay for permission to leave for Canada as soon as possible. Suddenly, unexciting Canada did not seem so terrible. Any officer who could tried to leave Boston, knowing that this posting would likely ruin his reputation.

A week after the troops began to move into rented housing, William Cooper, the clerk of the Boston Town Meeting, wrote to a correspondent in London to say that “Boston is now become a Garrison town.” Cooper did not mean only that one might come across soldiers in the street at any time of day or night. He meant that he felt the surveillance of the imperial state.

It was common custom for sentries anywhere in Britain to challenge people walking past a guard post, but Bostonians resented the practice. The merchant Lewis Gray, passing a guard post at midnight in early December, refused to answer the challenge, found himself detained, and retaliated by accusing the two sentries of assault and false imprisonment. Gray was not the only one who ignored the demand to identify himself. Colonel John Pomeroy complained to Governor Bernard of “many people, who refused to answer” and thereby created friction with the sentries. Bernard brought up Pomeroy’s complaint with his council, but their only response was that any fault lay with the sentries for harassing “respectable people.”

Samuel Adams, writing in the Boston Gazette as “Vindex,” argued that such challenges were inimical to Bostonians’ liberty. The very presence of troops was an affront; if the purpose of an army was to fight a war, an army that took up position within Boston could only be intended to deprive its free people of their liberty.

Richard Dana, Boston’s justice of the peace, certainly subscribed to this philosophy. When three Boston men accused thirty-three-year-old Private John Duxbury of assault after he challenged them that winter of 1768, Dana wholeheartedly supported the plaintiffs from the bench. It was the principle of military challenges to which he objected, Dana explained: “The matter of the Soldiers challenging people in the Streets was in itself nothing,” but such military practices were the thin edge of the wedge. Dana warned Bostonians not to respond to the challenges, “for if they once did that[,] other things would be introduced and steal upon them by degrees so as at last to reduce them to a state of slavery and make them subservient even to these Soldiers.” According to Bostonians like Dana, the very presence of soldiers put freedom at risk.

It was not only political types who found the presence of troops unpleasant. As one merchant wrote to his suppliers in London, “We are in such a situation here at present with regard to trade money growing so scarce and like to be worse that we are at a stand—not only so but having more than three Regiments of soldiers quartered in the town and a number of men of war in the Harbour makes the town very disagreeable so that if we are not soon relieved I believe many will leave the town.” The political liberty that Dana and others feared losing seemed to many Britons the foundation for their flourishing commerce. Letting soldiers wander around Boston streets seemed to put both trade and freedom at risk.

Citizens were right to be concerned about the effects of living in a “garrison town,” but they were wrong to think that they knew what those effects would be. The great changes that they would experience were not the loss of liberty, the obstreperousness of the soldiers, or even the violent confrontations that they feared. Instead, the quartering of British soldiers in Boston created a fundamental shift in the relationships between colonial and imperial, between citizen and soldier.

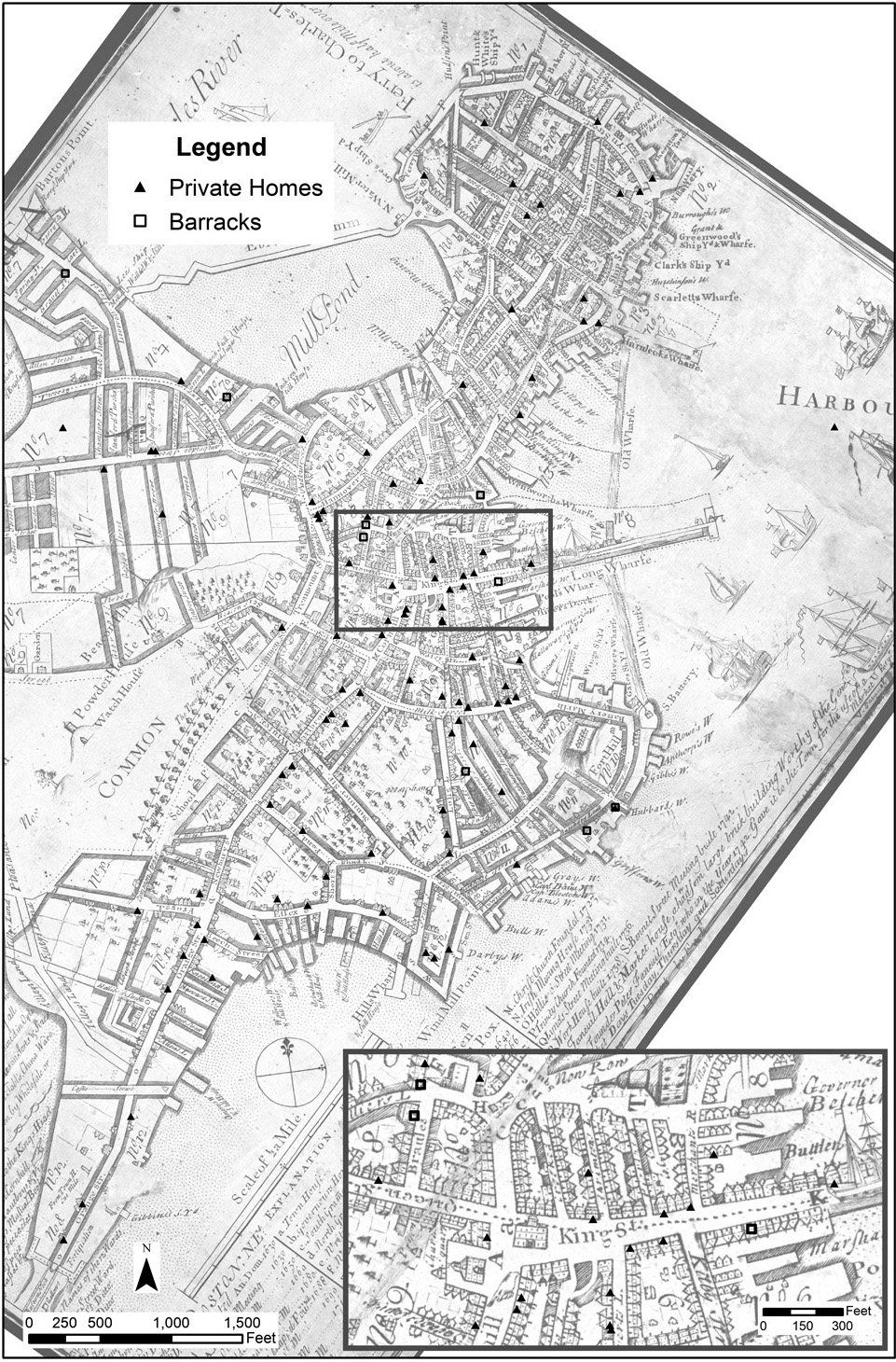

A map of Boston that displays the homes of some of the soldiers demonstrates clearly how completely soldiers’ families infiltrated the streets of the town. They lived in houses and outbuildings in every area of Boston. The family of Allan McGinnis, a member of the Sixty-Fourth Regiment, rented a house on Atkinson Street in the South End, while the wife of Patrick Walker lived in a house “in the yard of” James Cunningham on Orange Street, along with several other families from the Twenty-Ninth and Fourteenth Regiments. Richard Starkey of the Twenty-Ninth rented a house in the west side of Boston (known as New Boston) for his wife and two children. Hundreds of families needed homes; hundreds of Bostonians became landlords. As regimental families spread through the city, they created uneasy but definite connections between civilian and military communities.

Military families lived in private houses and barracks scattered throughout Boston.

The presence of some of these families could change a neighborhood, and not always for the better. Neighbors along Marlboro and School Streets complained about two military households, those of the black drummer John Bacchus and the white private Edward Montgomery. They had resided in Boston just a year when the neighbors protested that each “kept an ill govern’d & disorderly house, & entertaine’d certain lewd Idle & disorderly persons, at all hours as well by night as by day, and as well on Lords days as on other days, suffering them to Tipple in his house and profanely cursing and swearing, being a great grievance & common nuisance.” Eighteenth-century Bostonians’ complaints against disorderly houses were as numerous as the disorderly houses themselves, but the language of this complaint deserves attention. First, the vices of Sabbath breaking, illegal drinking, and bad language are commonly alleged not against disorderly houses but rather against the British army, whose culture was well known both to civilians and New Englanders who had served with the regulars in the Seven Years’ War. Second, John Bacchus was a black Jamaican, forty-three years old at the time of the complaint, and had already served sixteen years in the army. If his neighbors were offended by his race, they made no mention of it in their catalog of iniquities. Finally, the locals allege that this raucous behavior had been going on for the past six months. It is possible that these soldiers had lived elsewhere for the first six months of their time in Boston. It is also likely, however, that the first few months had not been so irritating. Perhaps, over time, Bostonians had begun to lose patience with their new neighbors.

Not every local relationship was so fraught. On the same date that seven Boston families complained about Bacchus and Montgomery, six different ones complained that John Timmins, another soldier from the Twenty-Ninth Regiment, was also keeping a disorderly house. Among Timmins’s neighbors were Thomas Wilkinson and his wife. Although Wilkinson signed on to the complaint against Timmins, he did not seem reflexively opposed to all soldiers as neighbors. In fact, he had an excellent relationship with Edward Montgomery and his wife, Isabella, about whom other Bostonians had complained. But Wilkinson had quite a different connection with Edward and Isabella: in the eighteenth-century equivalent of running to a neighbor’s house for a cup of sugar, Wilkinson occasionally sent his children to the Montgomerys’ home for coals to start his own fire.

Within the six months following the complaint, the Montgomery family had moved out of the city center into the North End, where Isabella Montgomery in particular continued to alienate many of her neighbors. After only a few months in her new house, Isabella had antagonized them to such a degree that one screamed at her that she hoped Isabella’s husband would die.

Whether cordial or heated, these complex relationships between civilian and military were replicated throughout the town. After living in Boston for a year and a half, several soldiers and their wives seemed quite comfortable spending time in the North End house of the jeweler John Wilme and his wife, Sarah. When the Bostonian David Cochran dropped by one evening in February, he found several of them visiting with the Wilmes and speaking in a way that managed to combine threats with advice. Sarah reported later that a member of the Fourteenth Regiment “did talk very much against the town” that evening, boasting that in any confrontation with townspeople “he would level his piece so as not to miss.” Ugly words, yes—but as Wilme explained it to Cochran, the soldiers also intended to warn Wilme and his family and friends to expect “disturbances.” Another soldier took Cochran aside and claimed that “blood would soon run in the streets of Boston,” but presumably not Cochran’s own. Somehow, general threats of violence went hand in hand with neighborly concern.

For seventy years, historians have argued that one reason why soldiers and local men were at odds throughout these years of occupation is that the privates, permitted to freelance, were willing to work in Boston establishments for less than the going rate of pay. But though there were many well-documented brawls in Boston, none seem related to pay. Private Patrick Doyne, for example, worked in a wigmaker’s shop with a few local apprentices. They seemed on good terms; the apprentices had a habit of dropping by to see Doyne and his wife in the evenings. Rather than creating enmity, shared workplaces could become venues where privates and townspeople could get to know one another.

There were limits to these friendships, however. Even as the Boston apprentices Richard Ward and Bartholomew Broaders visited in Private Patrick Doyne’s rooms, other soldiers came in and out, discussing brawls with the locals. Individual connections did not necessarily translate into an easy acceptance across the military-civilian divide. While sharing the town’s streets might have brought the two groups closer together—too close, some might have said—it did not incorporate soldiers completely into the civic community.

As their husbands and fathers met other apprentices and journeymen, military women and children were far more likely to see another side of Boston: its public institutions. In June 1769, the selectmen heard a rumor that smallpox had broken out at the regimental hospital that the army had established on the Boston Common. Worried that the infection would quickly make its way through the crowded city, they prevailed upon General Alexander Mackay to remove the ill man immediately to the Province Hospital, at the west end of Boston. It was too late. Although the town avoided a full-blown epidemic, new cases continued to crop up through the summer and fall. As smallpox made its way through the population, women and children related to the army came to know the town’s selectmen, its doctors, and, in particular, its quarantine hospitals. Their experiences demonstrated some of the limits of neighborliness, even as they shared some of their most intimate moments with the inhabitants of the town.

Jane Chambers again had to navigate private grief as she dealt with one of Boston’s public institutions. This time it was not a Congregational church. Less than a year after the terrifying illness of her child, disease struck again and forced the Chambers family into a strained relationship with the selectmen.

In the warm weeks of August 1769, Jane Chambers sat by one sickbed after another. Doctor Elisha Story came to see three of her children day after day, for four days. At last, yet another doctor came, this one sent by the town, and he diagnosed one of the children with smallpox, possibly the daughter who had already been so ill the year before. On August 23, a week later, Boston’s selectmen determined that Jane and her child posed a risk to the town’s public health. They sent the two not to the regimental hospital on the Boston Common but to the public hospital on the western edge of Boston, to isolate them from the others who shared their rented house. A week later, the selectmen’s agent transferred them again, this time to Rainsford Island, another “Pest House,” this one in Boston Harbor. Jane stayed on the island for a week, until she seemed to be out of danger. Then, on September 3, the selectmen ordered the director of the hospital to allow her to leave, provided that she had fresh clothes and was “sufficiently smoked,” or fumigated with sulfur. Meanwhile, her husband, Matthew, stayed in their rented house with their other children.

The spread of smallpox in Boston in 1769 was not particularly extensive, but how it had arrived was still a source of speculation. Jane and her daughter were among the handful of residents sent that summer to the smallpox hospital on Rainsford Island. Of the twenty-three family groups—primarily mothers and children—brought there for quarantine, less than a third were associated with the army. The selectmen attempted to reassure the town that the outbreak was limited and that the commanding officers had guaranteed—wrongly, as it turned out—that there was no smallpox either in the garrisons or the regimental hospital. The Bostonian Harbottle Dorr was incredulous and infuriated, in equal degrees, by this announcement. “It was brought by the soldiers,” he insisted. “Another article to be charged to the account of Gov. Bernard or who ever was the Instigator of Soldiers amongst us!” Dorr’s skepticism over the source of the outbreak was understandable, given the untrustworthiness of the army’s other recent claim. Only two days after General Mackay had assured the selectmen that there was no smallpox in any hospital or barrack that he oversaw, he was forced to return and admit that there was, in fact, a man in the regimental hospital with smallpox.

The Chambers family was not the only one in the neighborhood with smallpox that summer. As the disease spread, Dr. Miles Whitworth, who examined the ill for the selectmen, reported on sick soldiers’ wives and children on the western side of the city. In the middle of July, a Boston woman named Frances Tyler, who lived with her husband, Joseph, near the Orange Tree Inn, also fell ill. But the disease and the town treated the two families differently. Tyler refused to be quarantined in the public hospital; in response, the selectmen were willing to hang white flags around her house to warn others away. As the wife of a wealthy merchant, Tyler could push back against the selectmen’s attempt to regulate her body. She was, ironically, better able to separate herself from the town (or at least from the scrutiny of its officials) than was an outsider like Jane Chambers. When their illness was announced, as a public health concern, the selectmen noted both Tyler and Chambers by name and address, and in terms of each one’s relation to her husband.

Neither the Tylers nor the Chamberses escaped from smallpox unscathed, however. Frances Tyler died of the disease a week after her diagnosis. Unsurprisingly, this event merited a fulsome obituary in a Boston newspaper, an encomium to her “amiable mind and sweetness of her temper and disposition.” When Jane Chambers was allowed to leave Rainsford Island, the selectmen’s report made no mention of her child. But on September 2, the day before Chambers was released, a bill was submitted to the selectmen for the burial of six smallpox victims, including the “curing [putting in a tarred shroud and coffin] a sholyer’s [soldier’s] child and digging grave.” The unnamed casualty may well have been Jane’s child.

The few traces of these women in the public record reveal how strangely intertwined with and yet distant from the town of Boston and its officials soldiers’ families could be. The bill the town sexton presented to the town for the burial of smallpox victims itemized local women by name (“for carrying Mrs. Beals to the grave”), but not military ones. These women and children were listed solely as “soldier’s wife” or “soldier’s child.”

Soldiers’ families found themselves living the most personal, and sometimes the final, parts of their lives both within and outside the civilian world. The sorrows that Jane Chambers experienced in Boston can hardly be blamed on the town meeting; the death of her child was not itself the direct result of the town’s resistance to armed occupation. Yet that resistance created a world in which her family experienced occasional warm support but also heartless disregard and separation.