Chapter 2

Chapter 2

Chapter 2

Chapter 2

How the Winner-Take-All Economy Was Made

The winner-take-all economy—the hyperconcentration of rewards at the top that is the defining feature of the post-1970s American economy—poses three big mysteries: Who did it? How? And why? We have seen that the main suspect fingered by most investigators, Skill-Biased Technological Change, is at most a modest accomplice. Now, it is time to turn to the unusual suspect, American government and politics.

No less important, it is time to ask, if American government and politics did it, how? Only after understanding the basic, powerful ways in which government fueled the winner-take-all economy will we be in a position to delve into the “Why” questions: What were the motives behind the public policies that fostered winner-take-all? How, in a representative democracy, could public officials favor such a small slice of Americans for so long? That part of our investigation begins in chapter 3 with a whirlwind tour of American political history that seeks to uncover the reasons why, and the means by which, politicians in our capitalist constitutional democracy do—or do not—seek to redress imbalances of economic resources and power.

We face a high hurdle in our investigation. If there is one thing on which most economic experts seem to agree, it is that government and politics can’t be much of an explanation for the hyperconcentration of American incomes at the top. President Bush’s treasury secretary, Henry Paulson, may have tipped his Republican hat when he asserted in 2006 that inequality “is simply an economic reality, and it is neither fair nor useful to blame any political party.”1 (No one could doubt which party he thought was being unfairly and uselessly blamed.) Yet Paulson is hardly alone in his exculpatory judgment: Most economists on both sides of the political spectrum argue that government policy is at best a sideshow in the inequality circus. There are exceptions, of course. Nobel Laureate in Economics Paul Krugman has forcefully argued that policy is a crucial reason for rising inequality, and other experts have usefully examined the role of policy in specific areas.2 But the dominant perspective remains highly skeptical of attributing much influence to government—in part because there has yet to be a systematic accounting of the full range of things that American public officials have done (or, in some cases, deliberately failed to do) to propel the winner-take-all economy.

Think of this chapter as the opening argument of our case. Like any opening argument, it won’t address all the questions. In particular, it will leave almost entirely unaddressed the core mystery that motivates the rest of the book: Why have American politicians done so much to build up the winner-take-all economy? But as in any investigation, finding the right suspect—and showing just how powerful the case against that suspect is—represents the first step toward unraveling the larger mysteries that started the search.

Why Politics and Policy Are (Wrongly) Let Off

Much of the widespread doubt about the role of American politics and public policy in fostering rising inequality centers on a simple fact: The great bulk of the growth in inequality has been driven by rising inequalities in what people earn before government taxes and benefits. Simply put, those at the top are raking in a lot more from their jobs than they used to. The winner-take-all economy reflects a winner-take-all labor market.

Enter the doubters: It would be one thing, they argue, if government was taking much less from the rich in taxes or giving much less to the middle class in benefits than it used to. That would be a transparent case of government abetting inequality. But how, the skeptics ask, can government influence what people earn before they pay taxes or receive government benefits? On the conservative side, for example, Harvard’s Gregory Mankiw insists that while “some pundits are tempted to look inside the Beltway for a cause” of rising inequality, “policymakers do not have the tools to exert such a strong influence over pretax earnings, even if they wanted to do so.”3 On the liberal side, economist and former Clinton Treasury official Brad DeLong of the University of California at Berkeley says, “I can’t see the mechanism by which changes in government policies bring about such huge swings in pre-tax income distribution.”4

This skeptical response, however, makes three elemental mistakes.

The first is to miss the strong evidence that government is doing much less to reduce inequality through taxes and benefits at the very top of the income ladder. Here again, a fixation on inequality between big chunks of the income distribution misses the extent to which, at the very pinnacle, government policy has grown much more generous toward the fortunate. As we will show, this increasing solicitousness accounts for a surprisingly large part of the economic gains of America’s superrich.

Second, the skeptical response feeds off a mistaken presumption that if government and politics really matter, then the only way they can matter is through the passage of a host of new laws actively pursuing the redistribution of income to the top. We’ll show that a large number of new laws that greatly exacerbate inequality have been created, but we will also show that big legislative initiatives are not the only way to reshape how an economy works and whom it works for. Equally, if not more, important is what we will call “drift”—systematic, prolonged failures of government to respond to the shifting realities of a dynamic economy. We will have a lot to say about drift in this book, because the story of America’s winner-take-all economy isn’t just about political leaders actively passing laws to abet the rich, but also about political leaders studiously turning the other way (with a lot of encouragement from the rich) when fast-moving economic changes make existing rules and regulations designed to rein in excess at the top obsolete.

The third problem with the skeptical response goes even deeper: The skeptics suggest that the only way government can change the distribution of income is through taxation and government benefits. This is a common view, yet also an extraordinarily blinkered one. Government actually has enormous power to affect the distribution of “market income,” that is, earnings before government taxes and benefits take effect. Think about laws governing unions; the minimum wage; regulations of corporate governance; rules for financial markets, including the management of risk for high-stakes economic ventures; and so on. Government rules make the market, and they powerfully shape how, and in whose interests, it operates. This is a fact, not a statement of ideology. And it is a fact that carries very big implications.

Perhaps the biggest implication is that public policy really matters. The rules of the market make a huge difference for people’s lives. And what matters is not the broad label applied to what government does (“tax reform,” “health care reform”) but the underlying details that most commentators blithely ignore. As our investigation proceeds, we will see again and again that the devil truly is in the details of public policy. Policy is not a sideshow; in the modern age of activist government, it is often the main show.

To be sure, it is sometimes difficult to know exactly what the effects of these rules are. But there’s no question that these rules, taken together, have a massive cumulative impact. Just stop for a moment to contemplate how different economic affairs would be in our nation without basic property rights or government-regulated financial markets and you begin to appreciate how pervasive the role of government really is. And governments at different times and in different nations can and do make markets in very different ways, and with very different distributional results.

When these mistaken assumptions are corrected—when, that is, we look at what’s happened at the very top, take political efforts to block the adaptation of government policy seriously, and look at how markets have been politically reconstructed to aid the privileged—a conclusion that can’t be mistaken comes into view: Government has had a huge hand in nurturing America’s winner-take-all economy.

To be clear, we are not saying that technological shifts haven’t played a role too. Changes in information technology have fostered more concentrated rewards in fields of endeavor, such as sports and entertainment, where the ability to reach large audiences is the main determinant of economic return.5 Computers, increased global capital flows, and the development of new financial instruments have made it possible for savvy investors to reap (or lose) huge fortunes almost instantly—a point first made by Sherwin Rosen and elaborated by Robert Frank and Philip Cook in their 1995 book, The Winner-Take-All Society.6 But such technologically driven explanations have little to say about why the hyperconcentration of income at the top has been so much more pronounced in the United States than elsewhere. Nor do they come close to explaining just how concentrated economic gains have become.

For example, the “superstar” story of celebrities, artists, and athletes who now reach, and thus make, millions has a good deal of merit. As noted in chapter 1, however, these sorts of professions only account for a tiny share of the richest income group.

Table 1, based on a recent study of tax return data, shows that roughly four in ten taxpayers in the top 0.1 percent in 2004 were executives, managers, or supervisors of firms outside the financial industry (nearly three in ten were executives). By contrast, high-earners in the arts, media, and sports represented just 3 percent of this top-income group.

Table 1: Percentage of Taxpayers in

Top 0.1 Percent (Including Capital Gains), 2004

Executives, managers, supervisors (non-finance) |

40.8% |

Financial professions, including management |

18.4 |

Not working or deceased |

6.3 |

Lawyers |

6.2 |

Real estate |

4.7 |

Medical |

4.4 |

Entrepreneur not elsewhere classified |

3.6 |

Arts, media, sports |

3.1 |

Computer, math, engineering, technical (nonfinance) |

3.0 |

Business operations (nonfinance) |

2.2 |

Skilled sales (except finance or real estate) |

1.9 |

Professors and scientists |

1.1 |

Farmers & ranchers |

1.0 |

Other |

2.6 |

Unknown |

0.7 |

Source: Jon Bakija and Bradley T. Heim, “Jobs and Income Growth of Top Earners and the Causes of Changing Income Inequality: Evidence from U.S. Tax Return Data,” working paper, Williams College, Office of Tax Analysis (March 17, 2009), Table 1.

As for financial professionals, who make up a much larger proportion of the top 0.1 percent (nearly two in ten taxpayers), it strains credulity to say they are merely the talented tamers of technological change. After all, plenty of the so-called financial innovations that their complex computer models helped spawn proved to be just fancier (and riskier) ways of gambling with other people’s money, making quick gains off unsophisticated consumers, or benefiting from short-term market swings. Moreover, most of these “innovations” could occur only because of the failure to update financial rules to protect against the resulting risks—much to the chagrin of the rest of Americans who ended up bailing the innovators out. Former Fed chairman Paul Volcker was no doubt channeling a widespread sentiment when he said in 2009 that the last truly helpful financial innovation was the ATM.7

What is more, government policy not only failed to push back against the rising tide at the top in finance, corporate pay, and other winner-take-all domains, but also repeatedly promoted it. Government put its thumb on the scale, hard. What’s so striking is that it did so on the side of those who already had more weight. We can see this most clearly in the most transparent case of government abetting inequality: the gutting, over the course of three decades, of progressive taxation at the top of the economic ladder.

A Cut Above

The major rollback of taxation for those at the very top has received surprisingly little notice among today’s economic detectives. Most commentators appear to accept—with pleasure or displeasure, depending on their ideological persuasion—that the tax burden of the rich is not an important part of the rise of winner-take-all inequality.

But this is not true. Yes, as the Wall Street Journal editorial board never tires of reminding readers, the well-off are paying a larger share of the nation’s total income taxes than in the past. But that does not mean that the well-off are paying higher income tax rates. The amount of taxes we pay is a function not just of how steep tax rates are but also of how much we earn. And over the last generation, the well-off have earned more and more—so much more that they can pay a larger share of the nation’s income taxes and still pay a much lower overall rate on their massively larger incomes.

Moreover, income taxes are among the taxes that hit the rich hardest. When you take into account all federal taxes—including payroll taxes, which only hit the rich lightly, and corporate and estate taxes, which once hit the rich much harder than they do today—tax rates on the rich have fallen dramatically.

Perhaps most important, talking about the rich as a monolithic group makes no sense. As we have learned, there are the rich, and there are the rich. And what is most striking is that the latter group—the very, very, very rich—have enjoyed by far the greatest drop in their tax rates.

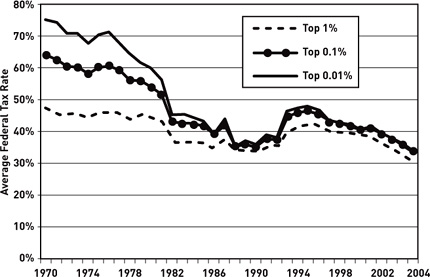

Figure 1, drawn from the research of the economists Thomas Piketty and Emmanuel Saez discussed in the last chapter, shows just how spectacular the decline has been for the tiny slivers of the top 1 percent we talked about earlier.8 This figure tracks the effective average federal rate—what people actually pay as a share of their reported income, not the official rate that enterprising lawyers and accountants make mincemeat of for the rich every day. As can be seen, those in the top 1 percent pay rates that are a full third lower than they used to be despite the fact that they are much richer than those in the top 1 percent were back in 1970. But as the top 1 percent is sliced into smaller and richer groups, the even more startling story becomes clear: The truly advantaged are paying a much smaller share of their reported income than they used to—at the very top (the richest 0.01 percent) less than half as large a share of income. They are not simply richer because their paychecks have grown; they’re richer because government taxes them much less heavily than it once did.

Figure 4: Average Federal Tax Rates for Top Income Groups, 1970–2004

Source: Thomas Piketty and Emmanuel Saez, “How Progressive is the U.S. Federal Tax System? A Historical and International Perspective,” Journal of Economic Perspectives 21, no. 1 (Winter 2007); data available at http://elsa.berkeley.edu/~saez/jep=results=standalone.xls.

Tax policy experts have a name for a tax code that taxes higher-income people at a higher rate: “progressive.” The federal tax code is still progressive overall. But what used to be a key feature of the code—its steep progressivity at the very top income levels—has simply disappeared. The richest of the rich now pay about the same overall rate as those who are merely rich. Indeed, though figure 1 doesn’t show this, the upper middle class—families, say, in the top 10 or 20 percent of the income distribution—are paying an average federal tax rate not much lower than that paid by the superrich. This is a pattern we will see again and again: dramatic benefits for the rich that are so precisely targeted that they are only visible when we put that tiny slice of Americans under our economic microscope. It is as if the government had developed the economic policy equivalent of smart bombs, except these bombs carry payloads of cash for their carefully selected recipients.

How much of the rise in winner-take-all outcomes does this three-decades-long tax-cutting spree account for? Unlike the effect of government on how much people earn, this is relatively easy to calculate (at least to a first approximation), and the numbers are staggering. The top 0.1 percent had about 7.3 percent of total national after-tax income in 2000, up from 1.2 percent in 1970. If the effect of taxes on their income had remained what it was in 1970, they would have had about 4.5 percent of after-tax income.9 Put more simply, if the effects of taxation on income at the top had been frozen in place in 1970, a very big chunk of the growing distance between the superrich and everyone else would disappear.

This dramatic change in tax policy didn’t happen magically. Starting in the 1970s, the people in charge of designing and implementing the tax code increasingly favored those at the very top. The change began before Reagan’s election, and continued well after the intellectual case had crumbled for the supply-side theories that had justified his big tax cuts. It resulted from a bidding war in which Democrats as well as Republicans took part, and involved cuts in estate and corporate taxes as well as in income taxes. The one big regularity was an impressive focus on directing benefits not just to the well-to-do but to the superrich. On provisions as diverse as the estate tax and the Alternative Minimum Tax, elected officials repeatedly chose courses of action that advantaged the very wealthy at the expense of the much larger group of the merely affluent.

All this occurred, moreover, even as Americans as a whole remained strongly supportive of making the richest pay more in taxes. In 1939, as the nation still grappled with the Great Depression, 35 percent of Americans agreed with the (very strongly worded) statement that “government should redistribute wealth by heavy taxes on the rich.” In 1998, 45 percent agreed; and in 2007, 56 percent did. Public concern about taxes has ebbed and flowed, but large majorities of Americans consistently say higher-income Americans pay too little in taxes and that corporate income taxes—which have fallen to less than 15 percent of all taxes—should be a key source of government revenue.10 And yet, taxes on the richest of Americans have, for more than thirty years, just kept coming down.

Not all of the tax-cutting has been as prominent as the estate tax cuts of 2001. Given public concerns about tax breaks for the wealthy, politicians have, not surprisingly, opted for more subtle means of achieving similar ends. One is slashing back enforcement of tax law. Call it “do-it-yourself tax cuts.” Roughly one out of every six dollars in owed taxes goes unpaid—literally, hundreds of billions a year.11 Not all of these dollars are owed by the rich, of course. But just as Willie Sutton robbed banks because “that’s where the money is,” tax evasion by the rich is where the money is. Most Americans, after all, have most of their taxes automatically taken out of their wages. Rich people and corporations, by contrast, are largely responsible for reporting their complex earnings and capital gains, and they have the will and the way to use intricate partnerships, offshore tax havens, and other devices that skirt or cross legal lines. Yet, as the investigative reporter David Cay Johnston has painstakingly documented, audits of high-income taxpayers and businesses have plummeted. About the only area where audits have gone up is among poorer taxpayers who claim the Earned Income Tax Credit.12

Another way public officials have cut the taxes of upper-income filers without passing new laws is by leaving in place loopholes through which rich Americans and their accountants shovel lightly taxed cash. Take one of the more egregious examples: the ability of private equity and hedge fund managers to treat much of their extraordinary incomes as capital gains, subject only to a 15 percent tax rate. (In 2006, the top twenty-five hedge fund managers earned nearly $600 million on average, with the richest, James Simons, taking in $1.7 billion.)13 The “carried interest” provision that allows this sweetheart deal is a bug in the tax code that predates the rise of hedge funds. But while this loophole is almost universally viewed as indefensible (and may finally be closed a bit in 2010), it has been protected for years by the fierce lobbying of its deep-pocketed beneficiaries and the strong backing of Wall Street supporters like Senator Chuck Schumer, Democrat of New York.

Given all the energy spent trying to pin rising inequality on relatively dubious suspects, it’s striking how little attention is paid to the very easily fingered culprit of declining tax rates on the rich. We’ve hardly begun laying out the full case for government’s role, but there’s no doubt that U.S. tax policy has exacerbated American hyperinequality through the demise of progressive taxation at the top of the economic ladder.

Reducing Redistribution

The fixation on inequality between large sections of the income distribution has obscured the extent to which government policy has grown more generous toward those at the very top. The second common oversight mentioned earlier—failing to take seriously how government policy can be undermined by deliberate efforts to block its being updated—has led observers to ignore the extent to which policy has become less generous toward the vast majority of Americans who have been on the losing side of rising inequality.

Indeed, a big clue in the cross-national statistics that points toward government policy as the suspect is that the United States stands out in its response to increases in inequality in market earnings since the 1970s. Elsewhere in the advanced industrial world, creeping tendencies toward greater economic disparities—whether due to globalization, technological change, or other broad economic or social forces—have been met with concerted, active resistance. In the United States, this pressure has proceeded with little government interference, aside from policies that have actively pushed it along.

We know this thanks to a major international research effort, the Luxembourg Income Study (LIS). For more than a decade, LIS researchers have been combing through national income data to examine how actively governments redistribute the income that people earn in the market, taking money from people higher on the economic ladder and distributing it to people lower. The LIS data suffer from the now-familiar problem that they are not very good at accounting for the incomes of the very richest. But they nonetheless offer a revealing picture of how countries have responded to rising inequality.

That picture may come as a surprise: We think of the welfare state as embattled, but in the majority of rich nations for which we have evidence, income redistribution over the past few decades has either held steady or actually risen. In many of these countries—and that includes our northern neighbor, Canada—inequality created by the market has been significantly softened by a greater government role.14

On American soil, the opposite has been true. Government is doing substantially less to reduce inequality and poverty below the highest rungs of the income ladder than it did a generation ago. We sometimes hear about expanding programs for the poor such as the Earned Income Tax Credit. But against the rising tide of inequality, these programs have represented fragile levees, crumbling under the weight of quickly moving water. Between 1980 and 2003, for example, the percentage by which government taxes and benefits reduced inequality (as measured by the Gini index, a common inequality standard) fell by more than a quarter.15

Can the absence of a government response to rising inequality really be treated as a form of policy? Absolutely—when it takes the form of “drift,” the deliberate failure to adapt public policies to the shifting realities of a dynamic economy.16

The idea of drift is simple, but central to understanding what has transpired in the United States. Major shifts in the economy and society change how public policies work. Think of how rising inflation erodes the value of the federal minimum wage. Workers at the very bottom of the economic ladder have seen their economic standing decline in part because the minimum wage has not been updated to reflect the rising price of consumer goods.17

And why has it not been updated? Because intense opponents of the minimum wage have worked tirelessly and effectively to prevent it from being increased to prior levels or pegged to inflation (a proposal that came close to passing in the 1970s). This has been every bit as much a political fight as, say, the Bush tax cuts of 2001 and 2003. But it is a far less visible fight, resulting not in big signing ceremonies, but in nothing happening. Our point is that nothing happening to key policies while the economy shifts rapidly can add up to something very big happening to Americans who rely on these policies.

Drift, in other words, is the opposite of our textbook view of how the nation’s laws are made. It is the passive-aggressive form of politics, the No Deal rather than the New Deal. Yet it is not the same as simple inaction. Rather, drift has two stages. First, large economic and social transformations outflank or erode existing policies, diminishing their role in American life. Then, political leaders fail to update policies, even when there are viable options, because they face pressure from powerful interests exploiting opportunities for political obstruction.

Drift is not the story of government taught in a civics classroom, but it is a huge and growing part of how policy is actually made in the civics brawl room that is contemporary American politics. Our nation’s fragmented political institutions have always made major policy reforms difficult. But, as we will see in the chapters to come, the slog has only grown more strenuous. Perhaps the biggest barrier in the last few decades has been the dramatically expanded use of the Senate filibuster. The insistence on sixty votes to cut off debate has allowed relatively small partisan minorities to block action on issues of concern to large majorities of Americans. Add to these institutional hurdles the increasing polarization of the two major political parties, and you have the perfect recipe for policy drift—and an increasingly threadbare safety net.

Still, a big part of the rise in American inequality has indeed occurred in the market, that is, in what people earn through their work and their assets even before America’s (dwindling) government benefits and (less and less progressive) taxes have a chance to do anything. Could government have any role in this part of rising inequality? Yes, because government has rewritten the rules of the market in ways that favor those at the top.

Rewriting the Rules

During the 2008 presidential campaign, the Republican candidate John McCain pilloried his opponent, Barack Obama, as the “Redistributor-in-Chief” because Obama called for letting the Bush tax cuts expire for families making more than $250,000 a year. The charge was revealing, not because Obama’s tax program was particularly redistributive, but because it reflected a view that is widespread not just among conservative politicians but also among experts and academics who study public policy. If this view has a title, it might be something like “The Rugged Individualist Meets Big Government.”

In this familiar story, there are two neatly defined worlds: the market, where the rugged individualist makes his home, and the government, which takes money from the rugged individualist and provides him and others with benefits. The popular version is summed up in tales of independent frontiersmen conquering the West, without the evident help of the U.S. Army or postal service or Lewis and Clark’s government-sponsored expedition. In a more contemporary vein, it is captured in the celebration of the can-do spirit of states like Alaska, from which John McCain’s running mate, Sarah Palin, prominently hailed. Despite Alaska’s status as the state most dependent on federal largesse on a per-person basis, politicians there persist in extolling the state’s self-made rise and criticizing the meddling hands of the federal government.18

Academics and policy experts are not immune to this view either—though their version generally lacks the ideological tinge. Indeed, in the preceding discussion of the changing role of government, we have largely been following the standard expert convention of parsing inequality into two parts: “market” inequality and “postgovernment” inequality. In this perspective, people earn money in the market thanks to their labor and assets. Governments then take that money through taxes and redistribute it through government transfers. It is a tidy view of the relationship between markets and governments. It is also utterly misleading.

Governments do redistribute what people earn. But government policies also shape what people earn in the first place, as well as many other fundamental economic decisions that consumers, businesses, and workers make. Practically every aspect of labor and financial markets is shaped by government policy, for good or ill. As the great political economist Karl Polanyi famously argued in the 1940s, even the ostensibly freest markets require the extensive exercise of the coercive power of the state—to enforce contracts, to govern the formation of unions, to spell out the rights and obligations of corporations, to shape who has standing to bring legal actions, to define what constitutes an unacceptable conflict of interest, and on and on.19 The libertarian vision of a night-watchman state gently policing an unfettered free market is a philosophical conceit, not a description of reality.

The intertwining of government and markets is nothing new. The frontier was settled because government granted land to the pioneers, killed, drove off, or rounded up Native Americans, created private monopolies to forge a nationwide transportation and industrial network, and linked the land settled with the world’s largest postal system. Similarly, the laissez-faire capitalism of the early twentieth century was underpinned by a government that kept unions at bay, created a stable money supply, erected trade barriers that sheltered the new manufacturing giants, protected entrepreneurs from debtors’ prison and corporations from liability, and generally made business the business of government.

When the political economy of the Gilded Age collapsed, it was government that reinvented American capitalism. With the arrival of the New Deal, the federal government took on a much more active role in redistributing income through the tax code and public programs. But the activist state that emerged did not just involve a new layer of redistribution. It fundamentally recast the national economy through the construction of a new industrial relations system, detailed and extensive regulation of corporations and financial markets, and a vast network of subsidies to companies producing everything from oil to soybeans. It also made huge direct investments in education and research—the GI Bill, the National Science Foundation, the National Institutes of Health—promoting the development of technological innovations and a skilled workforce that continue to drive American economic productivity.

And so it is with today’s winner-take-all economy. Redistribution through taxes and transfers—or rather its absence—is only part of the story, and not even the biggest part. Even the word “redistribution” is symptomatic of the pervasive distortions in contemporary discussion. It suggests the refashioning of a natural order by meddling politicians, a departure from market rewards. But the treatment of the market as some pre-political state of nature is a fiction. Politicians are there at the creation, shaping that “natural” order and what the market rewards. Beginning in the late 1970s, they helped shape it so more and more of the rewards would go to the top.

Beyond the stunning shifts in taxation already described, there were three main areas where government authority gave a huge impetus to the winner-take-all economy: government’s treatment of unions, the regulation of executive pay, and the policing of financial markets. These changes are so crucial to understanding how government rewrote the rules that we take them up now as a prelude to our larger story.

The Collapse of American Unions

No one who looks at the American economy of the last generation can fail to be struck by the precipitous decline of organized labor. From a peak of more than one in three workers just after World War II, union membership has declined to around one in nine. All the fall has occurred in the private sector, where unionization plummeted from nearly a quarter of workers in the early 1970s to just over 7 percent today.20 (By contrast, public-sector unionization increased, partially masking the private-sector collapse.)

This decline has abetted rising inequality in very obvious ways. Wages and benefits are more equal (and higher) where unions operate, and less educationally advantaged workers, in particular, have lost ground as the reach of unions has ebbed.21 But the near-extinction of private-sector unions has had a much broader and less appreciated effect on the distribution of American economic rewards. It has created a political and economic vacuum that has proven deadly to those seeking to redress winner-take-all inequality and friendly to those seeking to promote and consolidate it.

This is because organized labor’s role is not limited to union participation in the determination of wages. Much more fundamental is the potential for unions to offer an organizational counterweight to the power of those at the top. Indeed, while there are many “progressive” groups in the American universe of organized interests, labor is the only major one focused on the broad economic concerns of those with modest incomes. In the United States, and elsewhere, unions are the main political players pushing leaders to address middle-class economic concerns and resisting policy changes that promote inequality. Unions also have the resources and incentives to check corporate practices, such as bloated executive pay packages, that directly produce winner-take-all outcomes. Indeed, even with their current weakness, American unions (through operations like the AFL-CIO Office of Investment) represent one of only two organized groups providing a potential check on the unfettered autonomy of top executives and investors—the other being “investor collectives” like public pension systems and mutual funds. It is surely no coincidence that almost all the advanced industrial democracies that have seen little or no shift toward the top 1 percent have much stronger unions than does the United States.22

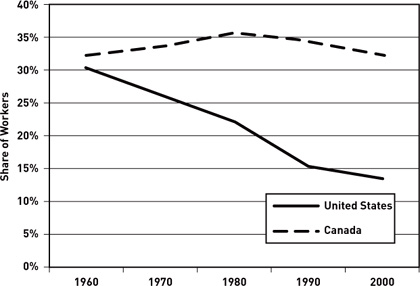

The conventional view is that American labor’s collapse was inevitable and natural, driven by global economic changes that have swept unions aside everywhere. But a quick glance abroad indicates that extreme union decline was not foreordained. While unions have indeed lost members in many Western nations (from a much stronger starting position), their presence has fallen little or not at all in others. In the European Union, union density fell by less than a third between 1970 and 2003. In the United States, despite starting from much lower levels, it fell by nearly half.23 Yet we do not need to gaze across the Atlantic to see a very different picture of union fortunes. In Canada, where the rate of unionization was nearly identical to the United States’ a few decades ago, unions have seen little decline despite similar worker attitudes toward unions in the two nations.

If economic forces did not dictate the implosion of American unions, perhaps American workers have simply lost interest in joining unions. Wrong again. In fact, nonunionized workers have expressed an increasing desire to be unionized since the early 1980s. In 2005, more than half of nonunionized private-sector workers said they wanted a union in their workplace, up from around 30 percent in 1984.24 Compared with other rich democracies, the United States stands out as the country with the greatest unfulfilled demand for union representation.25

Looking at surveys like these, it’s tempting to pin the blame on labor leaders for having their heads in the sand—and indeed, their initial response was overly complacent.26 By the late 1970s, however, unions were seeking reforms in labor laws that would have helped them maintain their reach. The most prominent was a major labor law reform bill in 1978. Unions made the bill their top political priority.27 Employers, energized and organized as they had not been for decades, mobilized in return, targeting Republicans and conservative Southern Democrats. Reform passed the House and commanded majority support in the Senate. But in a sign of the gridlock that would soon seem normal, the bill’s opponents were able to sustain a Senate filibuster—despite the presence of large Democratic majorities in the Senate.

The message of the failed reform drive was clear: Business had the upper hand in Washington and the workplace. In the words of economists Frank Levy and Peter Temin, the defeat sent “signals that the third man—government—was leaving the ring.”28 Even before Reagan took office, business adopted a much more aggressive posture in the workplace, newly confident that government would not intervene. When Reagan came to power, he reinforced the message by breaking a high-profile strike by air-traffic controllers, as well as stacking the National Labor Relations Board (NLRB) in favor of management. Within a few years, it was evident to all involved that the established legal framework for recognizing unions—the National Labor Relations Act, or NLRA—placed few real limits on increasingly vigorous antiunion activities. Writing in the Wall Street Journal in 1984, a prominent “union avoidance” consultant observed that the “current government and business climate presents a unique opportunity for companies… to develop and implement long-term plans for conducting business in a union-free environment.” The “critical test,” he continued, was whether corporations had the “intellectual discipline and foresight to capitalize on this rare moment in our history.”29

They did. Reported violations of the NLRA skyrocketed in the late 1970s and early 1980s.30 Meanwhile, strike rates plummeted, and many of the strikes that did occur were acts of desperation rather than indicators of union muscle.31 Nor did the assault abate in subsequent years. Between the mid-1980s and late 1990s, the share of NLRA elections featuring five or more union-avoidance tactics more than doubled, to over 80 percent.32 By 2007, less than a fifth of the declining number of workers organized in the private sector gained recognition through the traditional NLRA process, once the near-exclusive route to unionization.33

As the effective sidelining of the NLRA suggests, drift was the most powerful weapon of union opponents. Simply blocking federal actions that countered the economic and state-level shifts that were devastating unions, or that might weaken employers’ hand in union struggles, usually proved enough. In part, this reflected a harsh mathematical reality—the smaller the number of unions, the greater the cost per member needed to organize the vast nonunion sector. Once labor decline began to gain momentum, American unions confronted a harsh choice: devoting more of their evaporating resources to organizing, or gambling it on national and state political action to promote new rules.

Drift was especially dangerous to American unions for two other reasons. The first was their very uneven geographic and industrial reach. Well established in certain manufacturing industries in particular states, they were acutely vulnerable to the movement of manufacturing jobs to states where labor rights were more limited, as well as shifts in employment to sectors that had not previously been organized. These features made it easier for employers to pit one group of workers against another, and to move their activities—or threaten to move their activities—to areas where unions were weak or absent, inside or outside the United States.

The second reason is less well understood: American workers are unique in the extent to which they rely on individual firms to protect their health and retirement security.34 Government’s failure to update health-care and retirement policies left unionized companies in sectors from autos to airlines to steel highly vulnerable to the “legacy costs” associated with benefits for aging union workers (that is, the costs of benefits promised in the past, especially those granted to retirees). These costs—which in other rich democracies are either borne by all taxpayers or mandatory across firms—have contributed to slower employment growth in the unionized sector while stiffening corporations’ resistance to labor inroads.

A quick glance at Canada’s very different postwar experience drives these points home. As figure 5 shows, the gap in unionization between Canada and the United States has dramatically opened over the past four decades. The Canadian economist W. Craig Riddell has found that little of the divergence can be explained by structural features of the two nations’ economies, or even by varying worker propensities to join a union.35 Rather, the difference is due to the much lower (and declining) likelihood in the United States that workers who have an interest in joining a union will actually belong to one. Canadian law, for example, allows for card certification and first-contract arbitration (both features of the Employee Free Choice Act currently promoted by labor unions in the United States). It also bans permanent striker replacements, and imposes strong limits on employer propaganda.36 Moreover, because Canada has national health insurance and substantially lower medical costs, unionized sectors in Canada also bear far lower legacy costs. All this contrasts starkly with the United States, where national political leaders have done little to ease the burdens of private benefits and where aggressive antiunion activities by employers have met little resistance from public authorities.

Figure 5: Union Share of Wage and Salary Workers in the U.S. and Canada, 1960–2000

Sources: David Card, Thomas Lemieux, and W. Craig Riddell, “Unions and Wage Inequality,” Journal of Labor Research 25, no. 4 (2004): 519–59; Sylvia Allegreto, Lawrence Mishel, and Jared Bernstein, The State of Working America (Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press, 2008).

In short, American unions did not just happen to be in the way of a fast-moving economic train. They were pushed onto the tracks by American political leaders—in an era in which an organized voice would increasingly be needed to provide an effective counterweight to the rising influence of those at the top.

Blank Checks in the Boardroom

When the mercurial Home Depot CEO Bob Nardelli reaped a $210 million severance package upon his firing in 2007, even as the company’s stock fell, he became a poster child for the pay-without-performance world of executive compensation.37 Yet Nardelli was hardly the only corporate executive benefiting handsomely from the winner-take-all economy. As we saw earlier, the highest-paid executives in firms outside the financial sector account for around 40 percent of those in the top 0.1 percent.38

In historical perspective, the rise of executive pay has been nothing short of staggering.39 For roughly forty years between the New Deal and the mid-1970s, the pay of top officers in large firms rose at a modest rate.40 Around 1980, however, executive compensation started shooting up, and the pace of the acceleration increased in the 1990s. Despite dipping with the stock market in the early 2000s, executive pay has continued skyward. In 1965, the average chief executive officer (CEO) of a large U.S. corporation made around twenty-four times the earnings of the typical worker. By 2007, average CEO pay was accelerating toward three hundred times typical earnings. In that year, the average CEO of the 350 largest publicly traded companies made more than $12 million per year.41

Once again, the standard story is that top executives earn what they earn because they are so much more valuable to companies than they once were. Government has been a bystander as market forces have benignly played out.

Once again, however, the standard story is wrong. Executive pay is set in a distorted market deeply shaped by public policy. CEOs have been able to take advantage of a corporate governance system that allows them to drive up their own pay, creates ripe conditions for imbalanced bidding wars in which executives hold the cards, and prevents all but the most privileged insiders from understanding what is actually going on.

These arrangements are no accident. Over the last generation—through both changes in public policy and the failure to update government regulations to reflect changing realities—political leaders have promoted a system of executive compensation that grants enormous autonomy to managers, including significant indirect control over their own pay. Bob Nardelli’s outsized check could very well have had “Made possible by Washington” written on it.

As with the decline of unions, the experience of other rich nations shows that nothing about modern globalized capitalism makes extraordinary executive salaries inevitable or even likely. American CEOs are paid more than twice the average for other rich nations. In the country with the second-highest CEO pay levels—Switzerland—CEOs are paid on average around three-fifths of what American executives earn.42 Pay is not only lower in other rich nations; it also takes different forms. American CEOs, for example, receive much of their pay in short-term stock options, which not only lack transparency for stockholders but are also highly lucrative for CEOs who can create quick stock market gains through job cuts, restructuring, or creative accounting. Stock options are used in other nations, too, but they are much more often linked to long-term rather than short-term performance, as well as to firm performance relative to industry norms.43 Thus, for instance, options can be designed so that when the rising price of oil drives up the share price of energy companies, CEOs receive extra compensation only if their firm’s performance exceeds industry averages.

Defenders of American arrangements argue that they are in the best interests of shareholders.44 By negotiating with executives on behalf of the diffuse interests of those owning stock, this argument goes, boards of directors act as faithful defenders of shareholder value. Many of those who study how this process actually works are more doubtful. Looking at corporate governance in a number of rich democracies, the political economists Peter Gourevitch and James Shinn argue that a better description is “managerism,” a system in which managerial elites are in a strong position to extract resources.45 The financier John Bogle has contended that instead of an “ownership society” in which managers serve owners, the United States is moving toward an “agency society” in which managers serve themselves.46 Two of the nation’s leading experts on corporate compensation, Lucian Bebchuk and Jesse Fried, provide many findings more consistent with a “board capture” view than a “shareholder value” perspective. In their telling, boards are typically so beholden to CEOs—who influence the nomination of board members and have substantial influence over those members’ pay and perks—they offer little countervailing authority.47

The most revealing findings concern the design of executive compensation. Executive pay frequently departs from what would be expected to encourage good performance. Instead, corporate pay arrangements are shot through with what Bebchuk and Fried call “camouflage”: features designed to mitigate public outrage rather than limit excessive pay or link it more closely to value. To cite a few examples: Stock options are designed so that CEOs gain the upside of bull markets but are protected from bear markets. A huge chunk of executive pay is hidden in so-called deferred compensation—pay that’s put off to postpone taxes on interest and earnings—and in guaranteed-benefit pensions.

That’s right. In an era in which most workers receive no defined benefit in retirement, CEOs still do. IBM’s CEO, for example, was entitled to over $1 million a year in retirement benefits after about nine years of service to the company—an amount estimated to be worth about as much as he made while at the company.48 The economic rationale for this guaranteed payout was nonexistent. Indeed, unlike ordinary workers’ pensions, these massive executive benefits are not tax-free to the company (though they do shield executives from taxes on the interest that their pensions earn), and they can create staggering long-term liabilities for firms. But the camouflage they provided was substantial: IBM never had to report a cent of the payout as compensation.

The list goes on. Retired executives enjoy perks without parallel in the rest of the workplace. Guaranteed hours on corporate jets, chauffeurs, personal assistants, apartments, even lucrative consulting contracts—none has to be reported as executive pay. In 2001, executives at GE and Enron were guaranteed a rate of return on their deferred compensation of 12 percent, when long-run Treasury bills were paying out one-third of that. Coca-Cola’s CEO was able to defer taxes on $1 billion in compensation and investment earnings—gains that did not have to be reported in the company’s pay statements.49 In 2008, while Wal-Mart workers lost an average of 18 percent of their 401(k) holdings, Wal-Mart’s CEO, H. Lee Scott Jr., saw gains of $2.3 million in his $47 million retirement plan.50

Where were America’s political leaders while all this was happening? For the most part, they were either freeing up executives to extract more or, like police officers on the take, looking the other way. This is in sharp contrast to the experience abroad, where there have been substantial efforts to monitor executive pay and facilitate organized pushback against managerial power.51 In many nations, organized labor has served this countervailing role. But while American unions have tried to take on corporate pay, the broader challenges they have faced have severely hampered them. Another possible check on managerial autonomy, private litigation, was radically scaled back by mid-1990s legislation engineered by congressional Republicans. The bill had strong enough support from Democrats to pass over President Clinton’s veto.

Washington also opened the floodgates for the rise of stock options, the main conduit for the tide of money streaming from corporate coffers to top executives. During the 1990s, stock options became the central vehicle for enhancing executive compensation, comprising roughly half of executive pay by 2001. These options were typically structured in ways that lowered the visibility of high payouts and failed to create strong connections between compensation and managerial effectiveness, even though instruments for establishing such links were well known and widely used abroad.52 The value of options simply rose along with stock prices, even if stock price gains were fleeting, or a firm’s performance badly trailed that of other companies in the same sector. In the extreme but widespread practice of “backdating,” option values were reset retroactively to provide big gains for executives—a practice akin to repositioning the target after the fact to make sure the archer’s shot hit the bull’s-eye. But when the Financial Accounting Standards Board, which oversees accounting practices, tried to make firms report the costs of stock options like other compensation in the early 1990s, it was beaten back by a bipartisan coalition in the Senate galvanized by industry opposition.53 This is a textbook example of drift.

Recent efforts to increase board independence and capacity tell a similar story. In the early 2000s, after a series of massive scandals in which CEO self-dealing wiped out the assets of shareholders and employees, elected officials faced strong pressure to reform corporate governance. Still, the bill that eventually passed, called Sarbanes-Oxley after its two congressional sponsors, would most likely have died but for the collapse of WorldCom as the 2002 elections approached. Even then, corporations were able to beat back the sorts of reforms that would have put the most effective checks on managerial autonomy.54 Indeed, the nature of the compromise embodied in Sarbanes-Oxley is revealing. Managers accepted efforts designed to modestly increase transparency and regulate some of the most blatant conflicts of interest. At the same time, they quite effectively resisted efforts to increase the ability of shareholders to influence the governance of firms, including compensation practices.

Former chair of the SEC Arthur Levitt perfectly captures the political world that fostered ever-increasing executive payouts in his firsthand recollections of the unsuccessful battles over corporate reform in the 1990s:

During my seven and a half years in Washington… nothing astonished me more than witnessing the powerful special interest groups in full swing when they thought a proposed rule or a piece of legislation might hurt them, giving nary a thought to how the proposal might help the investing public. With laserlike precision, groups representing Wall Street firms, mutual fund companies, accounting firms, or corporate managers would quickly set about to defeat even minor threats. Individual investors, with no organized labor or trade association to represent their views in Washington, never knew what hit them.55

Finance Rules: Heads I Win, Tails You Lose

With the pillars of Wall Street now battered, it is easy to forget how dramatic the rise of the financial sector has been. Between 1975 and 2007, wages and salaries in the industry roughly doubled as a share of national earnings.56 The proportion of the economy comprising its activities exploded. Between 1980 and 2007, financial service companies expanded their share of company profits from around 13 percent to more than 27 percent. Even staid corporate giants got into the act. In 1980, GE earned 92 percent of its profit from manufacturing. In 2007, more than half of GE’s profits came from financial businesses.57

In part, this is simply a chapter of the broader rise of executive pay just chronicled. But the other part is the runaway rewards that have flowed into the pockets of the rich from America’s widening range of exotic new financial institutions. These rewards have involved the development of complex new financial products that, for most Americans, offered limited benefits and sometimes real economic risks. For the financial sector, however, the new instruments and expanding freedom to use them created astonishing opportunities: to increase the number of transactions (with intermediaries taking a cut on each one), to ratchet up leverage (and thus potential profits), and to increase the complexity and opacity in ways that advantaged insiders. Not coincidentally, all of these developments increased the risk to the system as a whole. However, that would be someone else’s problem—or, as economists gently put it, an “externality.” As Martin Wolf of the Financial Times observed acerbically in 2008, “No industry has a comparable talent for privatizing gains and socializing losses.”58

At the very top, those privatized gains were mind-boggling. Wages in the financial sector took off in the 1980s. The pace of the rise accelerated in the 1990s, and again after the millennium. In 2002, one had to earn $30 million to make it to the top twenty-five hedge fund incomes; in 2004, $100 million; in 2005, $130 million (when the twenty-fifth spot was occupied by William Browder, grandson of Earl Browder, onetime head of the Communist Party of the United States). A year later, the average for the top twenty-five had nearly doubled to $240 million; in 2007, it hit $360 million. That year, five hedge fund managers made $1 billion or more, with the top three weighing in around $3 billion.59 In the two years before they began reporting losses that dwarfed the profits of prior years and brought many of their stockholders to ruin, the venerable firms of Goldman Sachs, Merrill Lynch, Morgan Stanley, Lehman Brothers, and Bear Stearns paid their employees bonuses of $65.6 billion.60 The home address of the winner-take-all economy has been neither Hollywood nor Silicon Valley, but Wall Street.

Until a few years ago, high finance was depicted as the purest of markets. When politicians and analysts referenced the preferences of “Wall Street,” the phrase was taken (without irony) as a synonym for economic rationality itself, rather than as a set of specific interests. Yet financial markets, like others, are not pre-political. As Robert Kuttner detailed in his prescient 2007 book The Squandering of America, our financial system has always rested on an extensive set of government interventions.61 The legal environment for financial transactions governs such crucial issues as what constitutes insider dealing or conflicts of interest, how much monitoring and transparency there must be in major financial transactions, and what levels of leverage and risk are acceptable. In response to market failures on all these dimensions, the New Deal ushered in extensive new federal regulations designed to ensure investor confidence and align private ambitions more closely with broad economic goals such as financial stability.62

Over the last three decades, these relatively quiet and stable financial markets have given way to much more dynamic and unstable ones with far more pervasive effects on the rest of the economy. Some of the shift was clearly driven by changes in the nature of economic activity and the possibilities for financial intermediation. Technological innovation made possible the development of new financial instruments and facilitated spectacular experiments with securitization. Computers helped Wall Street transform from million-share trading days in the 1980s to billion-share trading days in the late 1990s, magnifying the possibilities for gains—and losses.63

The shredding of the post–New Deal rule book for financial markets did not, however, simply result from the impersonal forces of “financial innovation.” In Canada, for instance, government effectively resisted many of the efforts of financial interests to rewrite the rules—and Canada was largely spared the financial debacle of the past few years. The transformation of Wall Street reflected the repeated, aggressive application of political power. Some of that power was directed at removing existing regulations designed to protect against speculative excess and conflicts of interest. Some focused on thwarting would-be regulators who sought to update rules to address rapidly evolving financial realities. The net effect was not an idealized free market, but a playing field tilted in favor of those with power, connections, lack of scruples, and the ability to play the profitable but systematically risky new game.

Assessing the contribution of specific policy initiatives to the restructuring of financial markets is a matter of considerable controversy. That public action played a vital role, however, is less in doubt. A recent careful study by two enterprising economists, Thomas Philippon of New York University and Ariell Reshef of the University of Virginia, shows that regulatory restrictions on banking had been reduced below their pre–New Deal levels by the late 1990s.64 The changes included deregulation of bank branching (facilitating mergers and acquisitions), relaxation of the traditional separation of commercial and investment banking (which was finally repealed by the Gramm-Leach-Bliley Act of 1999), removing ceilings on interest rates, and repealing the decades-old separation between banks and insurance companies.

Other policy efforts were geared at keeping regulators away from emerging areas of financial activity—a classic form of policy drift. Consider the case of Wendy Gramm, George H. W. Bush’s chair of the Commodity Futures Trading Commission (CFTC). Only a few days before leaving office in early 1993, Gramm granted a “midnight order” that Enron had sought to allow it to trade in self-designed derivatives free of CFTC supervision.65 A few weeks later, she received a seat on Enron’s board. Her husband, Phil Gramm, was an even more prominent performer in the deregulation drama. As chair of the Senate Banking Committee, he was instrumental in laying down a little-noticed deregulatory milestone, the Commodity Futures Modernization Act. The 262-page bill—slipped into a far larger appropriations bill during the lame-duck fall 2000 session of Congress and signed into law by President Clinton—essentially exempted derivatives and other exotic instruments from oversight by the agencies that regulated more conventional financial assets.

Few now doubt that high finance profited at the expense of sensible regulations. But Philippon and Reshef’s research indicates just how intertwined private rewards and public rules have been. For decades after the stock market crash of 1929, they find, finance jobs were neither all that glamorous nor all that lucrative, but pretty much run-of-the-mill white-collar positions whose compensation tracked the rewards available elsewhere in the economy to those with similar skills. As deregulatory fever took hold, however, all this changed. Suddenly, and increasingly, financial professionals were earning much more than similarly educated workers. Perhaps as much as half of their expanding pay premium, Philippon and Reshef calculate, can be linked to the deregulation wave.66

Economists have a name for such government-created rewards: “rents”—money that accrues to favored groups not because of their competitive edge, but because public policy gives them specific advantages relative to their competitors. The rents in zip code 10005 have risen through the roof.

We now know that the price tag for two decades of deregulatory excess will be unconscionably high. Yet in one respect the success of the deregulatory agenda remains undeniable and largely intact: the massive enrichment of an extremely thin slice of American society. In the eight years leading up to the collapse of Bear Stearns and Lehman Brothers in 2008, the top five executives at each firm cashed out a total of roughly $2.4 billion in bonuses and equity sales that were not lost or clawed back when the firms went under.67 As one postcrash exposé explained the game, “Here’s how it goes. You bet big with someone else’s money. If you win, you get a huge bonus, based on the profits. If you lose, you lose someone else’s money rather than your own, and you move on to the next job. If you’re especially smart—like Lehman chief executive Dick Fuld—you take a lot of money off the table. During his tenure as CEO, Fuld made $490 million (before taxes) cashing in stock options and stock he received as compensation.”68

Friends in High Places

The myth of America’s winner-take-all economy is that government does not have much to do with it. Skyrocketing gains at the top are simply the impersonal beneficence of Adam Smith’s “invisible hand,” the natural outcome of free-market forces. Listen to Sanford Weill, the former chairman of Citigroup: “People can look at the last twenty-five years and say this is an incredibly unique period of time. We didn’t rely on somebody else to build what we built.”69 Weill may not have relied on “somebody else” during this “unique period.” He did, however, rely a great deal on government. When Citigroup formed in 1998, one of the top bankers involved joked at the celebratory press conference that any antitrust concerns could be dealt with easily: “Sandy will call up his friend, the President.”70 Within a few months, the financial industry had mounted a successful campaign to repeal the Glass-Steagall Act, which since the 1930s had prohibited powerful financial conglomerates of the sort Weill now headed on the grounds that they created conflicts of interest and impaired financial transparency and accountability. Leading the charge against Glass-Steagall was, yes, Sanford Weill.

The truth is that most people have missed the visible hand of government because they’ve been looking in the wrong place. They have talked about the minimum wage, the Earned Income Tax Credit, Medicaid for vulnerable children and families—in short, programs that help those at the bottom. The real story, however, is what our national political elites have done for those at the top, both through their actions and through their deliberate failures to act.

We have our suspect. The winner-take-all economy was made, in substantial part, in Washington. Yet identifying the main suspect only makes the core mystery more perplexing: How could this happen? No one expects the invisible hand of the market to press for equality. Yet there are good reasons for thinking that the visible hand of government will. Indeed, as we shall see in the next chapter, a long line of thinkers has argued that popular representation through democratic government creates powerful pressures for greater equality, as less-advantaged majorities use their political power to offset the economic power of those at the top.

That is clearly not what has happened in the United States over the last generation. Where governments in other democracies worked energetically to offset increasing inequality, public policies in the United States actively nurtured it. Why? How, in a country governed by majority rule, a country born of revolt against persistent differences in power and opportunity, could policy and government so favor such a narrow group, for so long, with so little real response? With the suspect identified, we now turn to the fundamental puzzle: What happened to American politics that precipitated these momentous changes?

This is not, it turns out, simply a question about contemporary American politics. In our search for clues regarding the transformation of American government since the 1970s, we kept coming upon striking parallels between our nation’s present struggles and moments of political decay and renewal in the past. The winner-take-all economy described in the last two chapters is distinctively of our time. But the process by which it arose—and the prospects for its reform—can only be seen with clear eyes if we take a longer historical perspective.

American government has a rap sheet, if you will. Repeatedly in our nation’s political history, Americans have found themselves buffeted by dislocating market forces while their government has seemed mired in gridlock and beholden to concentrated economic power. In the story of these past periods, we find the foundation of the answer to our central mystery.