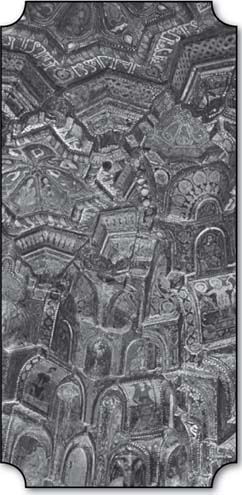

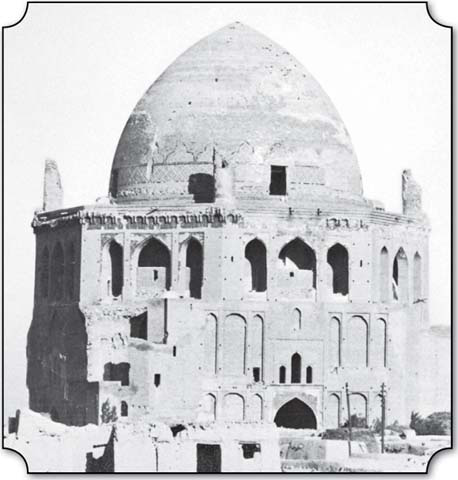

Bowl from Nishapur, lead-glazed earthenware with a slip decoration; in the Victoria and Albert Museum, London. Courtesy of the Victoria and Albert Museum, London

In order to answer whether or not there is an aesthetic, iconographic, or stylistic unity to the visually perceptible arts of Islamic peoples, it is first essential to realize that no ethnic or geographical entity was Muslim from the beginning. There is no Islamic art, therefore, in the way there is a Chinese art or a French art. Nor is it simply a period art, like Gothic art or Baroque art, for once a land or an ethnic entity became Muslim it remained Muslim, a small number of exceptions like Spain or Sicily notwithstanding. Political and social events transformed a number of lands with a variety of earlier histories into Muslim lands. But, since early Islam as such did not possess or propagate an art of its own, each area could continue, and in fact often did continue, whatever modes of creativity it had acquired. It may then not be appropriate at all to talk about the visual arts of Islamic peoples, and one should instead consider separately each of the areas that became Muslim: Spain, North Africa, Egypt, Syria, Mesopotamia, Iran, Anatolia, and India. Such, in fact, has been the direction taken by some recent scholarship. Even though tainted at times with parochial nationalism, the approach has been useful in that it has focused attention on a number of permanent features in different regions of Islamic lands that are older than and independent from the faith itself and from the political entity created by it. Iranian art, in particular, exhibits a number of features (certain themes such as the representation of birds or an epic tradition in painting) that owe little to its Islamic character since the 7th century. Ottoman art shares a Mediterranean tradition of architectural conception with Italy rather than with the rest of the Muslim world.

Such examples can easily be multiplied, but it is probably wrong to overdo their importance. For if one looks at the art of Islamic lands from a different perspective, a totally different picture emerges. The perspective is that of the lands that surround the Muslim world or of the times that preceded its formation. For even if there are ambiguous examples, most observers can recognize a flavour, a mood in Islamic visual arts that is distinguishable from what is known in East Asia (China, Korea, and Japan) or in the Christian West. This mood or flavour has been called decorative, for it seems at first glance to emphasize an immense complexity of surface effects without apparent meanings attached to the visible motifs. But it has other characteristics as well; it is often colourful, both in architecture and in objects; it avoids representations of living things; it gives much prominence to the work of artisans and counts among its masterpieces not merely works of architecture or of painting but also the creations of weavers, potters, and metalworkers. The problem is whether these uniquenesses of Islamic art, when compared to other artistic traditions, are the result of the nature of Islam or of some other factor or series of factors.

These preliminary remarks suggest at the very outset the main epistemological peculiarity of Islamic art: it consists of a large number of quite disparate traditions that, when seen all together, appear distinguishable from what surrounded them and from what preceded them through a series of stylistic and thematic characteristics. The key question is how this was possible, but no answer can be given before the tradition itself has been properly defined.

Such a definition can only be provided in history, through an examination of the formation and development of the arts through the centuries. For a static sudden phenomenon is not being dealt with, but rather a slow building up of a visual language of forms with many dialects and with many changes. Whether or not these complexities of growth and development subsumed a common structure is the challenging question facing the historian of this artistic tradition. What makes the question particularly difficult to answer is that the study of Islamic art is still relatively new. Many monuments are unpublished or at least insufficiently known, and only a handful of scientific excavations have investigated the physical setting of the culture and of its art. Much, therefore, remains tentative in the knowledge and appreciation of works of Islamic art.

Each artistic tradition has tended to develop its own favourite mediums and techniques. Some, of course, such as architecture, are automatic needs of every culture; and, for reasons to be developed later, it is in the medium of architecture that some of the most characteristically Islamic works of art are found. Other techniques, on the other hand, acquire varying forms and emphases. Sculpture in the round hardly existed as a major art form, and, although such was also the case of all Mediterranean arts at the time of Islam’s growth, one does not encounter the astounding rebirth of sculpture that occurred in the West. Wall painting existed but has generally been poorly preserved; the great Islamic art of painting was limited to the illustration of books. The unique feature of Islamic techniques is the astounding development taken by the so-called decorative arts—e.g., woodwork, glass, ceramics, metalwork, textiles. New techniques were invented and spread throughout the Muslim world—at times even beyond its frontiers. In dealing with Islam, therefore, it is quite incorrect to think of these techniques as the “minor” arts. For the amount and intensity of creative energies spent on the decorative arts transformed them into major artistic forms, and their significance in defining a profile of the aesthetic and visual language of Islamic peoples is far greater than in the instances of many other cultures. Furthermore, since, for a variety of reasons to be discussed later, the Muslim world did not develop until quite late the notion of “noble” arts, the decorative arts have reflected far better the needs and ambitions of the culture as a whole. The kind of conclusion that can be reached about Islamic civilization through its visual arts thus extends far deeper than is usual in the study of an artistic tradition, and it requires a combination of archaeological, art-historical, and textual information.

An example may suffice to demonstrate the point. Among all the techniques of Islamic visual arts, the most important one was the art of textiles. Textiles, of course, were used for daily wear at all social levels and for all occasions. But clothes were also the main indicators of rank, and they were given as rewards or as souvenirs by princes, high and low. They were a major status symbol, and their manufacture and distribution were carefully controlled through a complicated institution known as the tiraz. Major events were at times celebrated by being depicted on silks. Many texts have been identified that describe the hundreds of different kinds of textiles that existed. Since textiles could easily be moved, they became a vehicle for the transmission of artistic themes within the Muslim world and beyond its frontiers. In the case of this one technique, therefore, one is not dealing simply with a medium of the decorative arts but with a key medium in the definition of a given time’s taste, of its practical functions, and of the ways in which its ideas were distributed. The more unfortunate point is that the thousands of fragments that have remained have not yet been studied in a sufficiently systematic way, and in only a handful of instances has it been possible to relate individual fragments to known texts. When more work has been completed, however, a study of this one medium should contribute significantly to the commercial, social, and aesthetic history of Islam, as well as explain much of the impact that Islamic art had beyond the frontiers of the Muslim world.

The following survey of Islamic visual arts, therefore, will be primarily a historical one, for it is in development through time that the main achievements of Islamic art can best be understood. At the same time, other features peculiar to this tradition will be kept in mind: the varying importance of different lands, each of which had identifiable artistic features of its own, and the uniqueness of some techniques of artistic creativity over others.

Islamic visual arts were created by the confluence of two entirely separate kinds of phenomena: a number of earlier artistic traditions and a new faith. The arts inherited by Islam were of extraordinary technical virtuosity and stylistic or iconographic variety. All the developments of arcuated and vaulted architecture that had taken place in Iran and in the Roman Empire were available in their countless local variants. Stone, baked brick, mud brick, and wood existed as mediums of construction, and all the complicated engineering systems developed particularly in the Roman Empire were still used from Spain to the Euphrates. All the major techniques of decoration were still used, except for monumental sculpture. In secular and in religious art, a more or less formally accepted equivalence between representation and represented subject had been established. Technically, therefore, as well as ideologically, the Muslim world took over an extremely sophisticated system of visual forms; and, since the Muslim conquest was accompanied by a minimum of destruction, all the monuments, and especially the attitudes attached to them, were passed on to the new culture.

The second point about the pre-Islamic traditions is the almost total absence of anything from Arabia itself. While archaeological work in the peninsula may modify this conclusion in part, it does seem that Islamic art formed itself entirely in some sort of relationship to non-Arab traditions. Even the rather sophisticated art created in earlier times by the Palmyrenes or by the Nabataeans had almost no impact on Islamic art, and the primitively conceived haram in Mecca, the only pre-Islamic sanctuary maintained by the new faith, remained as a unique monument that was almost never copied or imitated despite its immense religious significance. The pre-Islamic sources of Islamic art are thus entirely extraneous to the milieu in which the new faith was created. In this respect the visual arts differ considerably from most other aspects of Islamic culture.

This is not to say that there was no impact of the new faith on the arts, but to a large extent it was an incidental impact, the result of the existence of a new social and political entity rather than of a doctrine. Earliest Islam as seen in the Qur’an or in the more verifiable accounts of the Prophet’s life simply do not deal with the arts, either on the practical level of requiring or suggesting forms as expressions of the culture or on the ideological level of defining a Muslim attitude toward images. In all instances, concrete Qur’anic passages later used for the arts had their visual significance extrapolated.

There is no prohibition against representations of living things, and not a single Qur’anic passage refers clearly to the mosque, eventually to become the most characteristically Muslim religious building. In the simple, practical, and puritanical milieu of early Islam, aesthetic or visual questions simply did not arise.

The impact of the faith on the arts occurred rather as the fledgling culture encountered the earlier non-Islamic world and sought to justify its own acceptance or rejection of new ways and attitudes. The discussion of two examples of particular significance illustrates the point. One is the case of the mosque. The word itself derives from the Arabic masjid, “a place where one prostrates one’s self (in front of God).” It was a common term in pre-Islamic Arabic and in the Qur’an, where it is applied to sanctuaries in general without restriction. If a more concrete significance was meant, the word was used in construct with some other term, as in masjid al-haram, to refer to the Meccan sanctuary. There was no need in earliest times for a uniquely Muslim building, for any place could be used for private prayer as long as the correct direction (qiblah, originally Jerusalem, but very soon Mecca) was observed and the proper sequence of gestures and pious statements was followed. In addition to private prayer, which had no formal setting, Islam instituted a collective prayer on Fridays, where the same ritual was accompanied by a sermon from the imam (leader of prayer, originally the Prophet, then his successors, and later legally any able-bodied Muslim) and by the more complex ceremony of the khutbah, a collective swearing of allegiance to the community’s leadership. This ceremony served to strengthen the common bond between all members of the ummah, the Muslim “collectivity,” and its importance in creating and maintaining the unity of early Islam has often been emphasized. There were two traditional locales for this event in the Prophet’s time. One was his private house, whose descriptions have been preserved; it was a large open space with private rooms on one side and rows of palm trunks making a colonnade on two other sides, the deeper colonnade being on the side of the qiblah. The Prophet’s house was not a sanctuary but simply the most convenient place for the early community to gather. Far less is known about the second place of gathering for the Muslim community. It was used primarily on major feast days, such as the end of the fasting period or the feast of sacrifice. It was called a musalla, literally “a place for prayer,” and musallas were usually located outside city walls. Nothing is known about the shape taken by musallas, but in all probability they were as simple as pre-Islamic pagan sanctuaries: large enclosures surrounded by a wall and devoid of any architectural or ornamental feature.

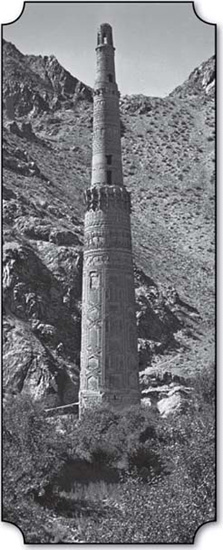

Altogether then there was hardly anything that could be identified as a holy building or as an architectural form. To be complete, one should add two additional features. One is an action, the call to prayer (adhan). It became, fairly rapidly, a formal moment preceding the gathering of the faithful. One man would climb on the roof and proclaim that God is great and that men must congregate to pray. There was no formal monument attached to the ceremony, though it eventually led to the ubiquitous minaret. The other early feature was an actual structure. It was the minbar, a chair with several steps on which the Prophet would climb in order to preach. The monument itself had a pre-Islamic origin, but Muhammad transformed it into a characteristically Muslim form.

With the exception of the minbar, only a series of actions was formulated in early Islamic times. There were no forms attached to them, nor were any needed. But, as the Muslim world grew in size, the contact with many other cultures brought about two developments. On the one hand there were thousands of examples of beautiful religious buildings that impressed the conquering Arabs. But, more importantly, the need arose to preserve the restricted uniqueness of the community of faithful and to express its separateness from other groups. Islamic religious architecture began with this need and, in ways to be described later, created a formal setting for the activities, ceremonies, and ideas that had been formless at the outset.

A second and closely parallel development of the impact of the Islamic religion on the visual arts is the celebrated question of a Muslim iconoclasm. As has already been mentioned, the Qur’an does not utter a word for or against the representation of living things. It is equally true that from about the middle of the 8th century a prohibition had been formally stated, and thenceforth it would be a standard feature of Islamic thought, even though the form in which it is expressed has varied from absolute to partial and even though it has never been totally followed. The justification for the prohibition tended to be that any representation of a living thing was an act of competition with God, for he alone can create something that is alive.

It is striking that this theological explanation reflects the state of the arts in the Christian world at the time of the Muslim conquest—a period of iconoclastic controversy. It may thus be suggested that Islam developed an attitude toward images as it came into contact with other cultures and that its attitude was negative because the arts of the time appeared to lead easily to dreaded idolatry. While it is only by the middle of the 8th century that there is actual proof of the existence of a Muslim doctrine, it is likely that, more or less intuitively, the Muslims felt a certain reluctance toward representations from the very beginning. For all monuments of religious art are devoid of any representations; even a number of attempts at representational symbolism in the official art of coinage were soon abandoned.

This rapid crystallization of Islamic attitudes toward images has considerable significance. For practical purposes, representations are not found in religious art, although matters are quite different in secular art. Instead there occurred very soon a replacement of imagery with calligraphy and the concomitant transformation of calligraphy into a major artistic medium. Furthermore, the world of Islam tended to seek means of representing the holy other than by images of men, and one of the main problems of interpretation of Islamic art is that of the degree of means it achieved in this search. But there is a deeper aspect to this rejection of holy images. Although the generally Semitic or specifically Jewish sources that have been given to Islamic iconoclasms have probably been exaggerated, the reluctance imposed by the circumstances of the 7th century transformed into a major key of artistic creativity the magical fear of visual imagery that exists in all cultures but that is usually relegated to a secondary level. This uniqueness is certainly one of the main causes of the abstract tendencies that are among the great glories of the tradition. Even when a major art of painting did develop, it remained always somehow secondary to the mainstream of the culture’s development.

Both in the case of the religious building and in that of the representations, therefore, it was the contact with pre-Islamic cultures in Muslim-conquered areas that compelled Islam to transform its practical and unique needs into monuments and to seek within itself for intellectual and theological justifications for its own instincts. The great strength of early Islam was that it possessed within itself the ideological means to put together a visual expression of its own, even though it did not develop at the very beginning a need for such an expression.

One last point can be made about the origins of Islamic art. It concerns the degree of importance taken by the various artistic and cultural entities conquered by the Arabs in the 7th and 8th centuries, for the early empire had gathered in regions that had not been politically or even ideologically related for centuries. During the first century or two of Islam, the main models and the main sources of inspiration were certainly the Christian centres around the Mediterranean. But the failure to capture Constantinople and to destroy the Byzantine Empire also made these Christian centres inimical competitors, whereas the whole world of Iran became an integral part of the empire, even though the conquering Arabs were far less familiar with the latter than with the former. A much more complex problem is posed by conversions, for it is through the success of the militant Muslim religious mission that the culture expanded so rapidly. Insofar as one can judge, it is the common folk, primarily in cities, who took over the new faith most rapidly; and thus there was added in early Islamic culture a folk element whose impact may have been larger than has hitherto been imagined.

These preliminary considerations on the origins of Islamic art have made it possible to outline several of the themes and problems that remained constant features of the tradition: a self-conscious sense of uniqueness when compared to others; a continuous reference to its own Qur’anic sources; a constant relationship to many different cultures; a folk element; and a variety of regional developments. None of these features remained constant, not even those aspects of the faith that affected the arts. But while they changed, the fact of their existence, their structural presence, remained a constant of Islamic art.

Of all the recognizable periods of Islamic art, this approximately 400-year period encompassing Islam’s first two major dynasties is by far the most difficult one to explain properly, even though it is quite well documented. There are two reasons for this difficulty. On the one hand, it was a formative period, a time when new forms were created that identify the aesthetic and practical ideals of the new culture. Such periods are difficult to define when, as in the case of Islam, there was no artistic need inherent to the culture itself. The second complication derives from the fact that Muslim conquest hardly ever destroyed former civilizations with its own established creativity. Material culture, therefore, continued as before, and archaeologically it is almost impossible to distinguish between pre-Islamic and early Islamic artifacts. Paradoxical though it may sound, there is an early Islamic Christian art of Syria and Egypt, and in many other regions the parallel existence of a Muslim and of a non-Muslim art continued for centuries. What did happen during early Islamic times, however, was the establishment of a dominant new taste, and it is the nature and character of this taste that has to be explained. It occurred first in Syria and Iraq, the two areas with the largest influx of Muslims and with the two successive capitals of the empire, Damascus under the Umayyads and Baghdad under the early ‘Abbasids. From Syria and Iraq this new taste spread in all directions and adapted itself to local conditions and local materials, thus creating considerable regional and chronological variations in early Islamic art.

From a historical point of view two major dynasties are involved. One is the Umayyad dynasty, which ruled from 661 to 750 and whose monuments are datable from 680 to 745. It was the only Muslim dynasty ever to control the whole of the Islamic-conquered world. The second dynasty is the ‘Abbasid dynasty; technically its rule extended as late as 1258, but in reality its princes ceased to be a significant cultural factor after the second decade of the 10th century. The ‘Abbasids no longer controlled Spain, where an independent Umayyad caliphate had been established; and in Egypt as well as in northeastern Iran a number of more or less independent dynasties appeared, such as the Tulunids or the Samanids. Although this conclusion is less certain than it used to be for the Samanids and northeast Iran, the initial impulse for the artistic creativity of these dynasties came from the main ‘Abbasid centres in Iraq. While in detailed studies it is possible to distinguish between Umayyad and ‘Abbasid art or between the arts of various provinces, the key features of the first three centuries of Islamic art (roughly through the middle of the 10th century) are the interplay between local or imperial impulses and the creation of new forms and functions.

Bowl from Nishapur, lead-glazed earthenware with a slip decoration; in the Victoria and Albert Museum, London. Courtesy of the Victoria and Albert Museum, London

It is possible to study these centuries as a succession of clusters of monuments, but, since there are so many of them, a study can easily end up as an endless list. It is preferable, therefore, to centre the discussion of Umayyad and ‘Abbasid monuments on the functional and morphological (form and structure) characteristics that identify the new Muslim world and only secondarily be concerned with stylistic progression or regional differences.

The one obviously new function developed during this period is that of the mosque, or masjid. The earliest adherents of Islam used the private house of the Prophet in Medina as the main place for their religious and other activities and musallas without established forms for certain holy ceremonies. The key phenomenon of the first decades that followed the conquest is the creation outside of Arabia of masjids in every centre taken over by the new faith. These were not simply or even primarily religious centres. They were rather the community centres of the faithful, in which all social, political, educational, and individual affairs were transacted. The first mosques were built primarily to serve as the restricted space in which the new community would take its own collective decisions. It is there that the treasury of the community was kept, and early accounts are full of anecdotes about the immense variety of events, from the dramatic to the scabrous, that took place in mosques. Since even in earliest times the Muslim community consisted of several superimposed and interconnected social systems, mosques reflected this complexity, and, next to large mosques for the whole community, tribal mosques and mosques for various quarters of a town or city are also known.

None of these early mosques has survived, and no descriptions of the smaller ones have been preserved. There do remain, however, accurate textual descriptions of the large congregational buildings erected at Kufah and Basra in Iraq and at al-Fustat in Egypt. At Kufah a larger square was marked out by a ditch, and a covered colonnade known as a zullah (a shady place) was put up on the qiblah side. In 670 a wall pierced by many doors was built in place of the ditch, and colonnades were put up on all four sides, with a deeper one on the qiblah. In all probability the Basra mosque was very similar, and only minor differences distinguished the ‘Amr ibn al-‘As mosque at al-Fustat. Much has been written about the sources of this type of building, but the simplest explanation may be that this is the very rare instance of the actual creation of a new architectural type. The new faith’s requirement for centralization, or a space for a large and constantly growing community, could not be met by any existing architectural form.

Almost accidentally, therefore, the new Muslim cities of Iraq created the hypostyle mosque (a building with the roof resting on rows of columns). A flexible architectural unit, a hypostyle structure could be square or rectangular and could be increased or diminished in size by the addition or subtraction of columns. The single religious or symbolic feature of the hypostyle mosque was a minbar (a pulpit) for the preacher, and the direction of prayer was indicated by the greater depth of the colonnade on one side of the structure.

The examples of Kufah, Basra, and al-Fustat are particularly clear because they were all built in newly created cities. Matters are somewhat more complex when discussing the older urban centres taken over by Muslims. Although it is not possible to generalize with any degree of certainty, two patterns seem to emerge. In some cases, such as Jerusalem and Damascus and perhaps in most cities conquered through formal treaties, the Muslims took for themselves an available unused space and erected on it some shelter, usually a very primitive one. In Jerusalem this space happened to be a particularly holy one—the area of the Jewish Temple built by Herod I the Great, which had been left willfully abandoned and ruined by the triumphant Christian empire. In Damascus it was a section of a huge Roman temple area, on another part of which there was a church dedicated to St. John the Baptist. Unfortunately too little is known about other cities to be able to demonstrate that this pattern was a common one. The very same uncertainty surrounds the second pattern, which consisted in forcibly transforming sanctuaries of older faiths into Muslim ones. This was the case at Hamah in Syria and at Yazd-e Khvast in Iran, where archaeological proof exists of the change. There are also several literary references to the fact that Christian churches, Zoroastrian fire temples, and other older abandoned sanctuaries were transformed into mosques. Altogether, however, these instances probably were not too numerous, because in most places the Muslim conquerors were quite anxious to preserve local tradition and because few older sanctuaries could easily serve the primary Muslim need of a large centralizing space.

During the 50 years that followed the beginning of the Muslim conquest, the mosque, until then a very general concept in Islamic thought, became a definite building reserved for a variety of needs required by the community of faithful in any one settlement. Only in one area, Iraq, did the mosque acquire a unique form of its own, the oriented hypostyle. Neither in Iraq nor elsewhere is there evidence of symbolic or functional components in mosque design. The only exception is that of the maqsurah (literally “closed-off space”), an enclosure, probably in wood, built near the centre of the qiblah wall. Its purpose was to protect the caliph or his replacement, for several attacks against major political figures had taken place. But the maqsurah was never destined to be a constant fixture of mosques, and its typological significance is limited.

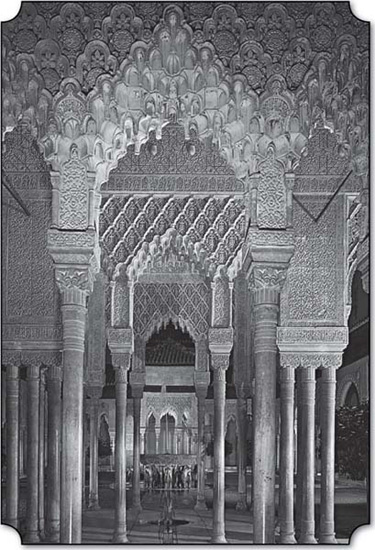

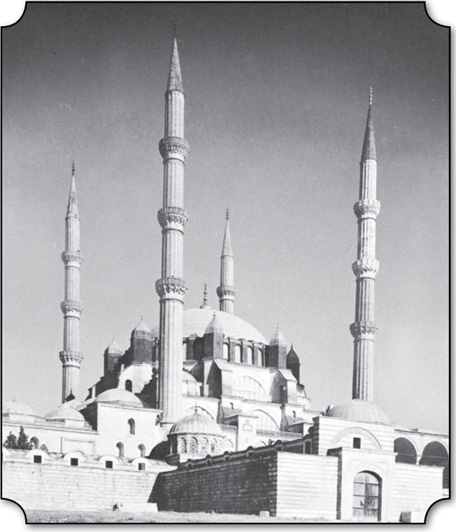

During the rule of the Umayyad prince al-Walid I (705–715), a number of complex developments within the Muslim community were crystallized in the construction of three major mosques, at Medina, Jerusalem, and Damascus. The very choice of these three cities is indicative: the city in which the Muslim state was formed and in which the Prophet was buried; the city held in common holiness by Jews, Christians, and Muslims, to which was rapidly accruing the mystical hagiography surrounding the Prophet’s ascension into heaven; and the ancient city that became the capital of the new Islamic empire. A first and essential component of al-Walid’s mosques was, thus, their imperial character; they were to symbolize the permanent establishment of the new faith and of the state that derived from it. They were no longer purely practical shelters but willful monuments.

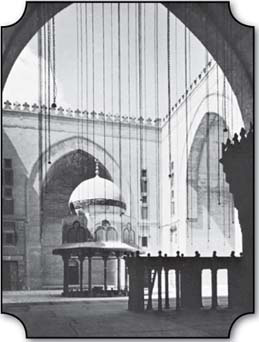

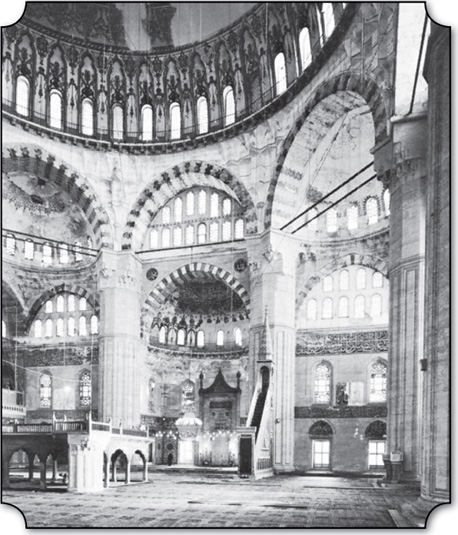

Although the plans of al-Aqsa Mosque in Jerusalem and of the mosque of Medina can be reconstructed with a fair degree of certainty, only the one at Damascus has been preserved with comparatively minor alterations and repairs. In plan the three buildings appear at first glance to be quite different from each other. The Medina mosque was essentially a large hypostyle with a courtyard. The colonnades on all four sides were of varying depth. Al-Aqsa Mosque consisted of an undetermined number of naves (possibly as many as 15) parallel to each other in a north–south direction. There was no courtyard because the rest of the huge esplanade of the former Jewish temple served as the open space in front of the building. The Umayyad Mosque of Damascus is a rectangle 515 by 330 feet (157 by 100 metres) whose outer limits and three gates are parts of a Roman temple (a fourth Roman gate on the qiblah side was blocked). The interior consists of an open space surrounded on three sides by a portico and of a covered space of three equal long naves parallel to the qiblah wall that are cut in the middle by a perpendicular nave.

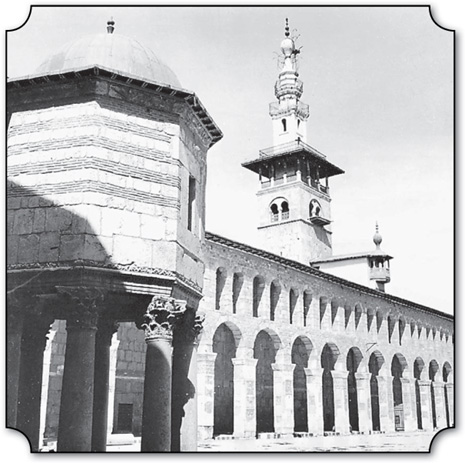

Courtyard of the Great Mosque of Damascus, Syria, built by al-Walid I, 705–715, showing the Bayt al-Mal (treasury) on the left, beyond which can be seen one of the three towers of the first Muslim minaret. Paul Almasy

The three buildings share several important characteristics. They are all large spaces with a multiplicity of internal supports; and although only the Medina mosque is a pure hypostyle, the Jerusalem and Damascus mosques have the flexibility and easy internal communication characteristic of a hypostyle building. All three mosques exhibit a number of distinctive new practical elements and symbolic meanings. Many of these occur in all mosques; others are only known in some of them. The mihrab, for example, appears in all mosques. This is a niche of varying size that tends to be heavily decorated. It occurs in the qiblah wall, and, in all probability, its purpose was to commemorate the symbolic presence of the Prophet as the first imam, although there are other explanations. It is only in Damascus that the ancient towers of the Roman building were first used as minarets to call the faithful to prayer and to indicate from afar the presence of Islam (initially minarets tended to exist only in predominantly non-Muslim cities). All three mosques are also provided with an axial nave, a wider aisle unit on the axis of the building, which served both as a formal axis for compositional purposes and as a ceremonial one for the prince’s retinue. Finally, all three buildings were heavily decorated with marble, mosaics, and woodwork. At least in the mosque of Damascus, it is further apparent that there was careful concern for the formal composition—a balance between parts that truly makes this mosque a work of art. This is particularly evident in the successful relationship established between the open space of the court and the facade of the covered qiblah side.

When compared to the first Muslim buildings of Iraq and Egypt, the monuments of al-Walid are characterized by the growing complexity of their forms, by the appearance of uniquely Muslim symbolic and functional features, and by the quality of their construction. While the dimensions, external appearance, and proportions of any one of them were affected in each case by unique local circumstances, the internal balance between open and covered areas and the multiplicity of simple and flexible supports indicate the permanence of the early hypostyle tradition.

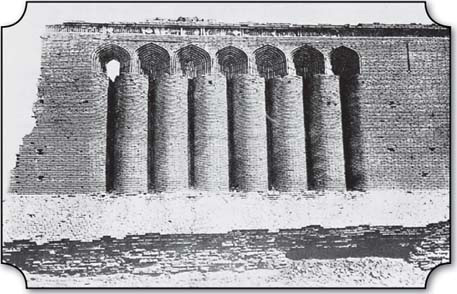

Either in its simplest form, as in Medina, or in its more formalized shape, as in Damascus, the hypostyle tradition dominated mosque architecture from 715 to the 10th century. As it occurs at Nishapur in northeastern Iran, Siraf in southern Iran, al-Qayrawan (Kairouan) in Tunisia, and Córdoba in Spain, it can indeed be considered as the classic early Islamic type. Its masterpieces occur in Iraq and in the West. The monumentalization of the early Iraqi hypostyle is illustrated by the two ruined structures in Samarra’, with their enormous sizes (790 by 510 feet [240 by 156 metres] for one and 700 by 440 feet [213 by 135 metres] for the other), their multiple entrances, their complex piers, and, in one instance, a striking separation of the qiblah area from the rest of the building. The best preserved example of this type is the mosque of Ibn Tulun at Cairo (876–879), where a semi-independent governor, Ahmad ibn Tulun, introduced Iraqi techniques and succeeded in creating a masterpiece of composition.

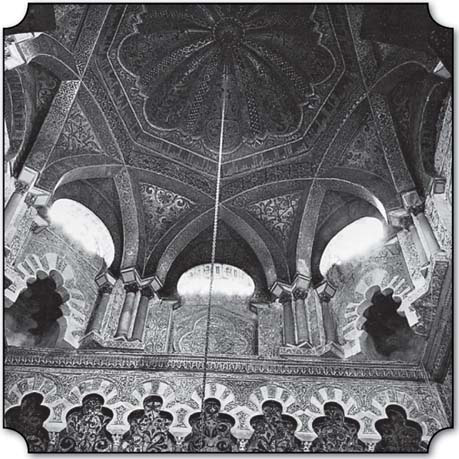

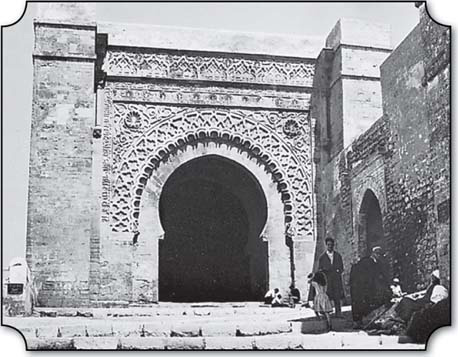

Two classic examples of early mosques in the western Islamic world of interest are preserved in Tunisia and Spain. In al-Qayrawan the Great Mosque was built in stages between 836 and 866. Its most striking feature is the formal emphasis on the building’s T-like axis punctuated by two domes, one of which hovers over the earliest preserved ensemble of mihrab, minbar, and maqsurah. At Córdoba the earliest section of the Great Mosque was built in 785–786. It consisted simply of 11 naves with a wider central one and a court. It was enlarged twice in length, first between 833 and 855 and again from 961 to 965 (it was in the latter phase that the celebrated maqsurah and mihrab, comprising one of the great architectural ensembles of early Islamic art, were constructed). Finally, in 987–988 an extension of the mosque was completed to the east that increased its size by almost one-third without destroying its stylistic unity. The constant increases in the size of this mosque are a further illustration of the flexibility of the hypostyle and its adaptability to any spatial requirement. The most memorable aspects of the Córdoba mosque, however, lie in its construction and decoration. The particularly extensive and heavily decorated mihrab area exemplifies a development that started with the Medina mosque and would continue: an emphasis on the qiblah wall.

Although the hypostyle mosque was the dominant plan, it was not the only one. From very early Islamic times, a fairly large number of aberrant plans also occur. Most of them were built in smaller urban locations or were secondary mosques in larger Muslim cities. It is rather difficult, therefore, to evaluate whether their significance was purely local or whether they were important for the tradition as a whole. Since a simple type of square subdivided by four piers into nine-domed units occurs at Balkh in Afghanistan, at Cairo, and at Toledo, it may be considered a pan-Islamic type. Other types, a single square hall surrounded by an ambulatory, or a single long barrel-vault parallel or perpendicular to the qiblah, are rarer and should perhaps be considered as purely local. These are particularly numerous in Iran, where it does seem that the mainstream of early Islamic architecture did not penetrate very deeply.

The function of the mosque, the central gathering place of the Muslim community, became the major and most original completely Muslim architectural effort. The mosque was not a purely religious building, at least not at the beginning; but, because it was restricted to Muslims, it is appropriate to consider it as such. This, however, was not the only type of early Islamic building to be uniquely Muslim. Three other types can be defined architecturally, and a fourth one only functionally.

The first type, the Dome of the Rock in Jerusalem, is a unique building. Completed in 691, this masterwork of Islamic architecture is the earliest major Islamic monument. Its octagonal plan, use of a high dome, and building techniques are hardly original, although its decoration is unique. Its purpose, however, is what is most remarkable about the building. Since the middle of the 8th century, the Dome of the Rock has become the focal centre of the most mystical event in the life of the Prophet: his ascension into heaven from the rock around which the building was erected. According to an inscription preserved since the erection of the dome, however, it would seem that the building did not originally commemorate the Prophet’s ascension but rather the Christology of Islam and its relationship to Judaism. It seems preferable, therefore, to interpret the Dome of the Rock as a victory monument of the new faith’s ideological and religious claim on a holy city and on all the religious traditions attached to it.

The second distinctly Islamic type of religious building is the little-known ribat. As early as in the 8th century, the Muslim empire entrusted the protection of its frontiers, especially the remote ones, to warriors for the faith (murabitun, “bound ones”) who lived, permanently or temporarily, in special institutions known as ribats. Evidence for these exist in Central Asia, Anatolia, and North Africa. It is only in Tunisia that ribats have been preserved. The best one is at Susah, Tunisia; it consists of a square fortified building with a single fairly elaborate entrance and a central courtyard. It has two stories of private or communal rooms. Except for the prominence taken by an oratory, this building could be classified as a type of Muslim secular architecture. Since no later example of a ribat is known, there is some uncertainty as to whether the institution ever acquired a unique architectural form of its own.

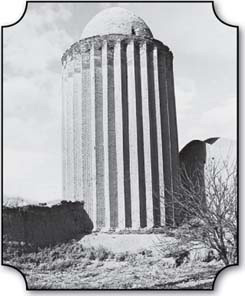

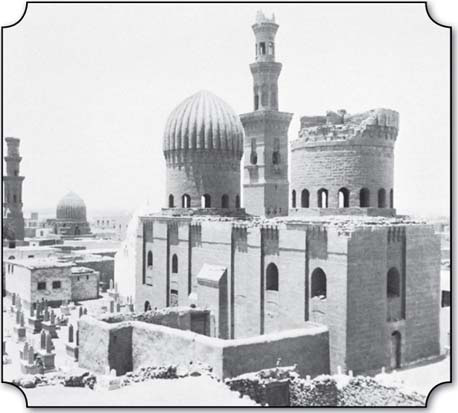

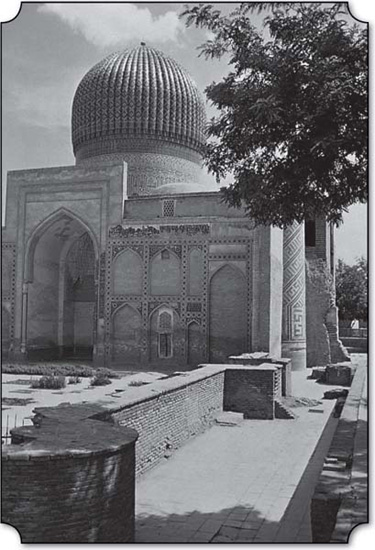

The last type of religious building to develop before the end of the 10th century is the mausoleum. Originally Islam was strongly opposed to any formal commemoration of the dead. But three independent factors slowly modified an attitude that was eventually maintained only in the most strictly orthodox circles. One factor was the growth of the Shi‘ite heterodoxy, which led to an actual cult of the descendants of the Prophet through his son-in-law ‘Ali. The second factor was that, as Islam strengthened its hold on conquered lands, a wide variety of local cultic practices and especially the worship of certain sacred places began to affect the Muslims, resulting in a whole movement of Islamization of ancient holy places by associating them with deceased Muslim heroes and holy men or with prophets. The third factor is not, strictly speaking, religious, but it played a major part. As more or less independent local dynasties began to grow, they sought to commemorate themselves through mausoleums. Not many mausoleums have remained from these early centuries, but literary evidence is clear on the fact that the Shi‘ite sanctuaries of Karbala’ and al-Najaf, both in Iraq, and Qom, Iran, already possessed monumental tombs. The masterpieces of early funerary architecture occur in Central Asia, such as the royal mausoleum of the Samanids (known incorrectly as the mausoleum of Esma‘il the Samanid) at Bukhara (before 942), which is a superb example of Islamic brickwork. In some instances a quasi-religious character was attached to the mausoleums, such as the one at Tim (976).

The fourth kind of Muslim building is the madrasah, an institution for religious training set up independently of mosques. It is known from texts that such privately endowed schools existed in the northeastern Iranian world as early as in the 9th century, but no description exists of how they were planned or how they looked.

Whereas the functions of the religious buildings of early Islam could not have existed without the new faith, the functions of secular Muslim architecture have a priori no specifically Islamic character. This is all the more so since one can hardly point to a significant new need or habit that would have been brought from Arabia by the conquering Muslims and since so little was destroyed in the conquered areas. It can be assumed, therefore, that all pre-Islamic functions such as living, trading, and manufacturing continued in whatever architectural setting they may have had. Only one exception is certain. With the disappearance of Sasanian kingship, the pre-Islamic Iranian imperial tradition ceased, and elsewhere conquered minor kings and governors left their palaces and castles. A new imperial power was created, located first in Damascus, then briefly in the northern Syrian town of al-Rusafah, and eventually in Baghdad and Samarra’ in Iraq. New governors and, later, almost independent princes took over provincial capitals. In all instances, there is no reason to assume that for an architecture of power or of pleasure early Muslims would have felt the need to modify pre-Islamic traditions. In fact there is much in early Islamic secular architecture that can be used to illustrate secular arts elsewhere—in Byzantium, for example, or even in the West.

Three factors contributed to the evolution of a new secular architecture. One was that the accumulation of an immense wealth of ideas, workers, and money in the hands of the Muslim princes settled in Syria and Iraq gave rise to a unique palace architecture. The second factor was the impetus given to urban life and to trade. New cities were founded from Sijilmassah on the edge of the Moroccan Sahara to Nishapur in northeastern Iran, and 9th-century Arab merchants traded as far away as China. Thus the second topic, to be treated below, will be the urban design and commercial architecture. The third factor is that, for the first time since Alexander the Great, a world extending from the Mediterranean to India became culturally unified. As a result, decorative motifs, design ideas, structural techniques, and artisans and architects—which until then had belonged to entirely different cultural traditions—were available in the same places. Early Islamic princely architecture has become the best known and most original aspect of early Islamic secular buildings.

There are basically three kinds of these princely structures. The first type consists of 10 large rural princely complexes found in Syria, Palestine, and Transjordan dating from roughly 710 to 750: al-Rusafah, Qasr al-Hayr East, Qasr al-Hayr West, Jabal Says, Khirbat Minyah, Khirbat al-Mafjar, Mshatta, Qasr ‘Amrah, Qasr al-Kharanah, and Qasr al-Tubah. Apparently these examples of princely architecture belong to a group of more than 60 ruined or only textually identifiable rural complexes erected by Umayyad princes. These structures were each part of a major agricultural or trade centre, some of which were developed even before the Muslim conquest. Private palaces were built, notably at al-Rusafah, Qasr al-Hayr West, Khirbat al-Mafjar, Qasr ‘Amrah, and Mshatta. These must be considered as early medieval equivalents of the villae rusticae so characteristic in the ancient Roman period. Although each of these had a number of idiosyncrasies that were presumably inspired by the needs and desires of its owner, all of these structures tend to share a number of features that can best be illustrated by Khirbat al-Mafjar.

This palace, the richest of them all, contained a residential unit consisting of a square building with an elaborate entrance, a porticoed courtyard, and a number of rooms or halls arranged on two floors. Few of these rooms seem to have any identifiable function, although at Khirbat al-Mafjar a private oratory, a large meeting hall, and an anteroom leading to a cool underground pool have been identified. The main throne room was on the second floor above the entrance. Its plan is not known but probably resembled the preserved throne rooms or reception halls at Qasr ‘Amrah and Mshatta, which consisted of a three-aisled hall ending in an apse (semicircular or polygonal domed projection) in the manner of a Roman basilica.

Next to an official residence, there usually was a small mosque, generally a miniaturized hypostyle in plan. The most original feature of these establishments was the bath. The bathing area itself is comparatively small, but every bath had its own elaborate entrance and contained a large hall that, at least in the instance of Khirbat al-Mafjar, was heavily decorated and of an unusual shape. It would appear that these halls were for pleasure—places for music, dancing, and probably occasional orgies. In some instances, as at Qasr ‘Amrah, the same setting may have been used for both pleasure and formal receptions.

These palaces are important illustrations of the luxurious taste and way of life of the new aristocrats, who settled in the countryside. This aspect of these establishments is peculiar to the Umayyad dynasty in Syria and Palestine. Outside of this area and period only one comparable structure has been found—at Ukhaydir in Iraq, which dates from the early ‘Abbasid period. A number of princely residences of the Central Asian or North African countryside are still too little known but appear not to have had the same development. The other important lesson to draw from them is that few of their features are original. All of them derive from the architectural vocabulary of pre-Islamic times, and, for as interesting as these monuments are, they are not part of the Islamic tradition.

A second type of princely architecture—the urban palace—has been preserved only in texts or literary sources, with the exception of the palace at Kufah in Iraq. Datable from the very end of the 7th century, this example of princely architecture seems to have functioned both as a residence and as the centre of government. This dual function is reflected in the use of separate building units and in the dearth of architectural decoration, which suggests that it reflected an austere official taste. Scholars do not have sufficient information to define these early urban official buildings of the Muslims.

Also poorly documented is a development in urban aristocratic buildings that seems to have begun with the ‘Abbasids during the last decades of the 8th century. This involved the construction of smaller palaces, probably pavilions in the midst of gardens in or around major cities.

The third type of early Islamic princely architecture is the palace-city. Several of these huge palaces are part of the enormous mass of ruins at Samarra’, the temporary ‘Abbasid capital from 838 to 883. Jawsaq al-Khaqani, for instance, is a walled architectural complex nearly one mile to a side that in reality is an entire city. It contains a formal succession of large gates and courts leading to a cross-shaped throne room, a group of smaller living units, basins and fountains, and even a racetrack. Too little is known about the architectural details of these huge walled complexes to lead to more than very uncertain hypotheses. Their existence, however, suggests that they were settings for the very elaborate ceremonies developed by the ‘Abbasid princes, especially when receiving foreign ambassadors. An account, for instance, in Khatib al-Baghdadi’s Ta’rikh Baghdad (“History of Baghdad”) of the arrival in Baghdad of a Byzantine envoy in 914 illustrates this point. The meeting with the caliph was preceded by a sort of formal presentation intended to impress the ambassador with the Muslim ruler’s wealth and power. Treasures were laid down, thousands of soldiers and slaves in rich clothes guarded them, lions roared in the gardens, and on gilded artificial trees mechanical devices made silver birds chirp. The ceremony was a fascinating mixture of a traditional attempt to re-create paradise on earth and a rather vulgar exhibition of wealth that required a huge space, as in the Samarra’ palaces. Another important aspect of these palace-cities is that they became part of a myth. The walled enclosure in which thousands lived a life unknown to others and into which simple mortals did not penetrate without bringing their own shroud was transformed into legend. It became the mysterious City of Brass of The Thousand and One Nights, and it is from its luxurious glory that occasionally a caliph such as Harun al-Rashid escaped into the “real” world. Even though there is inadequate information on the ‘Abbasid palace-city, it was clearly a unique early Islamic creation, and its impact can be detected from Byzantium to Hollywood.

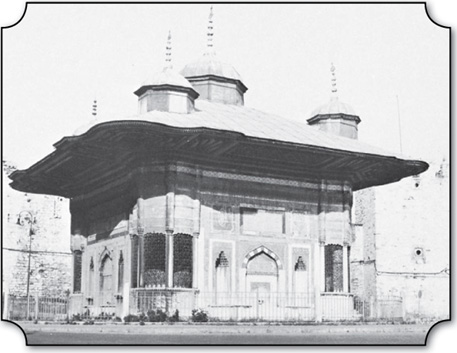

Islamic secular architecture has left considerable information about cities, for systematic urbanization was one of the most characteristic features of early Muslim civilization. It is much too early to draw any sort of conclusion about the actual physical organization of towns, about their subdivisions and their houses, for only at al-Fustat (Cairo) and Siraf in Iran is the evidence archaeologically clear, and much of it has not yet been properly published. In general it can be said that there does not seem to have been any idealized master plan for the internal arrangement of an urban site in contradistinction to Hellenistic or Roman towns. Even mosques or palaces were often located eccentrically and not in the middle of the town. Extraordinary attention was paid to water distribution and conservation, as demonstrated by the magnificent 9th-century cisterns in Tunisia, the 9th-century Nilometer (a device to measure the Nile’s level) in Cairo, and the elaborate dams, canals, and sluices of Qasr al-Hayr in Syria. The construction of commercial buildings on a monumental scale occurred. The most spectacular example is the caravansary of Qasr al-Hayr East, with its magnificent gate.

The concern for palaces and cities that characterized early Islamic secular architecture shows itself most remarkably in the construction of Baghdad between 762 and 766–767 by the ‘Abbasid caliph al-Mansur. It was a walled round city whose circular shape served to demonstrate Baghdad’s symbolic identity as the navel of the universe. A thick ring of residential quarters was separated by four axial, commercial streets entered through spectacular gates. In the centre of the city there was a large open space with a palace, a mosque, and a few administrative buildings. By its size and number of inhabitants, Baghdad was unquestionably a city; however, its plan so strongly emphasized the presence of the caliph that it was also a palace.

The early Islamic period, on the whole, did not innovate much in the realm of building materials and technology but utilized what it had inherited from older traditions. Stone and brick continued to be used around the Mediterranean, while mud brick usually covered with plaster predominated in Iraq and Iran, with a few notable exceptions like Siraf, where a masonry of roughly cut stones set in mortar was more common. The most important novelty was the rapid development in Iraq of a baked brick architecture in the late 8th and 9th centuries. Iraqi techniques were later used in Syria at al-Raqqah and Qasr al-Hayr East and in Egypt. Iranian brickwork appears at Mshatta in Jordan. Wood was used consistently but has usually not been very well preserved.

As supports for roofs and ceilings, early Islamic architecture used walls and single supports. Walls were generally continuous, often buttressed with half towers, and rarely (with exceptions in Central Asia) were they articulated or broken by other architectural features. The most common single support was the base–column–capital combination of Mediterranean architecture. Most columns and capitals were either reused from pre-Islamic buildings or were directly imitated from older models. In the 9th century in Iraq a brick pier was used, a form that spread to Iran and Egypt. Columns and piers were covered with arches. Most often these were semicircular arches; the pointed, or two-centred, arch was known, but it does not seem that its property of reducing the need for heavy supports had been realized. The most extraordinary technical development of arches occurs in the Great Mosque at Córdoba, where, in order to increase the height of the building in an area with only short columns, the architects created two rows of superimposed horseshoe arches. Almost immediately they realized that such a succession of superimposed arches constructed of alternating stone and brick could be modified to create a variety of patterns that would alleviate the inherent monotony of a hypostyle building. A certain ambiguity remains, however, as to whether ornamental effect or structural technology was the predominate concern in the creation of these unique arched columns.

The majority of early Islamic ceilings were flat. Gabled wooden roofs, however, were erected in the Muslim world west of the Euphrates and simple barrel vaults to the east. Vaulting, either in brick or in stone, was used, especially in secular architecture. Domes were employed frequently in mosques, consistently in mausoleums, and occasionally in secular buildings. Almost all domes are on squinches (supports carried across corners to act as structural transitions to a dome). Most squinches, as in the al-Qayrawan domes, are classical Greco-Roman niches, which transform the square room into an octagonal opening for the dome. In Córdoba’s Great Mosque a complex system of intersecting ribs is encountered, while at Bukhara the squinch is broken into halves by a transverse half arch. The most extraordinary use of the squinch occurs in the mausoleum at Tim, where the surface of this structural device is broken into a series of smaller three-dimensional units rearranged into a sort of pyramidal pattern. This rearrangement is the earliest extant example of muqarnas, or stalactite-like decoration that would later be an important element of Islamic architectural ornamentation.

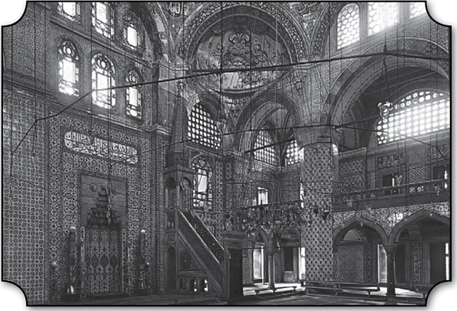

Early Islamic architecture is most original in its decoration. Mosaics and wall paintings followed the practices of antiquity and were primarily employed in Syria, Palestine, and Spain. Stone sculpture existed, but stucco sculpture, first limited to Iran, spread rapidly throughout the early Islamic world. Not only were stone or brick walls covered with large panels of stucco sculpture, but this technique was used for sculpture in the round in the Umayyad palaces of Qasr al-Hayr West and Khirbat al-Mafjar. The latter was a comparatively short-lived technique, although it produced some of the few instances of monumental sculpture anywhere in the early Middle Ages. A variety of techniques borrowed from the industrial arts were used for architectural ornamentation. The mihrab wall of al-Qayrawan’s Great Mosque, for example, was covered with ceramics, while fragments of decorative woodwork have been preserved in Jerusalem and Egypt.

Dome of the mihrab in the Great Mosque of Córdoba, Spain, c. 961. Fritz Henle/Photo Researchers

The themes and motifs of early Islamic decoration can be divided into three major groups. The first kind of ornamentation simply emphasizes the shape or contour of an architectural unit. The themes used were vegetal bands for vertical or horizontal elements, marble imitations for the lower parts of long walls, chevrons or other types of borders on floors and domes, and even whole trees on the spandrels or soffits (undersides) of arches as in the Umayyad Mosque of Damascus or the Dome of the Rock; all these motifs tend to be quite traditional, being taken from the rich decorative vocabularies of pre-Islamic Iran or of the ancient Mediterranean world.

The second group consists of decorative motifs for which a concrete iconographic meaning can be given. In the Dome of the Rock and the Umayyad Mosque of Damascus, as well as possibly the mosques of Córdoba and of Medina, there were probably iconographic programs. It has been shown, for example, that the huge architectural and vegetal decorative motifs at Damascus were meant to symbolize a sort of idealized paradise on earth, while the crowns of the Jerusalem sanctuary are thought to have been symbols of empires conquered by Islam. But it is equally certain that this use of visual forms in mosques for ideological and symbolic purposes was not easily accepted, and most later mosques are devoid of iconographically significant themes. The only exceptions fully visible are the Qur’anic inscriptions in the mosque of Ibn Tulun at Cairo, which were used both as a reminder of the faith and as an ornamental device to emphasize the structural lines of the building. Thus the early Islamic mosque eventually became austere in its use of symbolic ornamentation, with the exception of the mihrab, which was considered as a symbol of the unity of all believers.

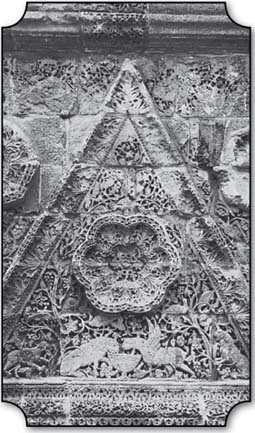

The third type of architectural decoration consists of large panels, most often in stucco, for which no meaning or interpretation is yet known. These panels might be called ornamental in the sense that their only apparent purpose was to beautify the buildings in which they were installed, and their relationship to the architecture is arbitrary. The Mshatta facade’s decoration of a huge band of triangles is, for instance, quite independent of the building’s architectural parts. Next to Mshatta, the most important series of examples of the third type of ornamentation come from Samarra’, although striking examples are also to be found at Khirbat al-Mafjar, Qasr al-Hayr East and West, al-Fustat, Siraf, and Nishapur. Two decorative motifs were predominately used on these panels: a great variety of vegetal motifs and geometric forms. Copied consistently from Morocco to Central Asia, the aesthetic principles of this latter type of a complex overall design influenced the development of the principle of arabesque ornamentation.

Triangle stone relief from the facade of Mshatta in Jordan, early 8th century; in the Museum of Islamic Art, Pergamon Museum, National Museums of Berlin. Courtesy of the Islamisches Museum, Staatliche Museen zu Berlin

Very little is known about early Islamic gold and silver objects, although their existence is mentioned in many texts as well as suggested by the wealth of the Muslim princes. Except for a large number of silver plates and ewers belonging to the Sasanian tradition, nothing has remained.

For entirely different reasons it is impossible to present any significant generalities about the art of textiles in the early Islamic period. Problems of authenticity are few. Dating from the 10th century are a large number of Buyid silks, a group of funerary textiles with plant and animal motifs as well as poetic texts. Very little order has yet been made of an enormous mass of often well-dated textile fragments, and therefore, except for the Buyid silks, it is still impossible to identify any one of the textile types mentioned in early medieval literary sources. Furthermore, since it can be assumed that pre-Islamic textile factories were taken over by the Muslims and since it is otherwise known that textiles were easily transported from one area of the Muslim world to the other or even beyond it, it is still very difficult to define Islamic styles as opposed to Byzantine or to Coptic ones.

The most important medium of early Islamic decorative arts is pottery. Initially Muslims continued to sponsor whatever varieties of ceramics had existed before their arrival. Probably in the last quarter of the 8th century new and more elaborate types of glazed pottery were produced. This new development did not replace the older and simpler types of pottery but added a new dimension to the art of Islamic ceramics. This section treats only the most general characteristics of Islamic ceramics.

The area of initial technical innovation seems to have been Iraq. Trade with Central Asia brought Chinese ceramics to Mesopotamia, and Islamic ceramists sought to imitate them. It is probably in Iraq, therefore, that the technique of lustre glazing was first developed in the Muslim world. This gave the surface of a clay object a metallic, shiny appearance. Egypt also played a leading part in the creation of the new ceramics. Since the earliest datable lustre object (a glass goblet with the name of the governor who ruled in 773) was Egyptian, some scholars feel that it was in Egypt and not Iraq that lustre was first used. Early pottery was also produced in northeastern Iran, where excavations at Afrasiyab (Samarkand) and Nishapur have brought to light a new art of painted underglaze pottery. Its novelty was not so much in the technique of painting designs on the slip and covering them with a transparent glaze as in the variety of subjects employed.

While new ceramic techniques may have been sought to imitate other mediums (mostly metal) or other styles of pottery (mostly Chinese), the decorative devices rapidly became purely and unmistakably Islamic in style. A wide variety of motifs were combined: vegetal arabesques or single flowers and trees; inscriptions, usually legible and consisting of proverbs or of good wishes; animals that were usually birds drawn from the vast folkloric past of the Near East; occasionally human figures drawn in a strikingly abstract fashion; geometric designs; all-over abstract patterns; single motifs on empty fields; and simple splashes of colour, with or without underglaze sgraffito designs (i.e., designs incised or sketched on the body or the slip of the object). All of these motifs were used on both the high-quality ceramics of Nishapur and Samarkand as well as on Islamic folk pottery.

Although ceramics has appeared to be the most characteristic medium of expression in the decorative arts during the early Islamic period, it has only been because of the greater number of preserved objects. Glass was as important, but examples have been less well preserved. A tradition of ivory carving developed in Spain, and the objects dating from the last third of the 10th century onward attest to the high quality of this uniquely Iberian art. Many of these carved ivories certainly were made for princes; therefore it is not surprising that their decorative themes were drawn from the whole vocabulary of princely art known through Umayyad painting and sculpture of the early 8th century. These ivory carvings are also important in that they exemplify the fact that an art of sculpture in the round never totally disappeared in the Muslim world—at least in small objects.

There are three general points that seem to characterize the art of the early Islamic period. It can first be said that it was an art that sought self-consciously, like the culture sponsoring it, to create artistic forms that would be identifiable as being different from those produced in preceding or contemporary non-Islamic artistic traditions. Although initially some arts used or adapted other traditions, in ceramics and the use of calligraphic ornamentation, the early Islamic artist invented new techniques and a new decorative vocabulary. Whatever the nature of the phenomenon, it was almost always an attempt to identify itself visually as unique and different. Since there was initially no concept about what should constitute an Islamic tradition in the visual arts, the early art of the Muslims often looks like only a continuation of earlier artistic styles, forms, subjects, and techniques. Many mosaics, silver plates, or textiles, therefore, were not considered to be Islamic until the late 20th century. In order to be understood, then, as examples of the art of a new culture, these early buildings and objects have to be seen in the complete context in which they were created. When so seen they appear as conscious choices by the new Islamic culture from its immense artistic inheritance.

A second point of definition concerns the question of whether there is an early Islamic style or perhaps even several styles in some sort of succession. The fascinating fact is that there is a clear succession only in those artistic features that are Islamic inventions—nonfigurative ornament and ceramics. Elsewhere, especially in palace art, the Muslim world sought to relate itself to an earlier and more universal tradition of princely art; its monuments, therefore, are less Islamic than typological.

Finally, the geographical peculiarities of early Islamic art must be reiterated. Its centres were Syria, Iraq, Egypt, northwestern Iran, and Spain. Of these, Iraq was probably the most originally creative, and it is from Iraq that a peculiarly Islamic visual koine (a commonly accepted and understood system of forms) was derived and spread throughout the Islamic world. This development, of course, is logical since the capital of the early empire and some of the first purely Muslim cities were in Iraq. In western Iran, in Afghanistan, in northern Mesopotamia, and in Morocco the more atypical and local artistic traditions were more or less affected by the centralized imperial system of Iraq. This tension between a general pan-Islamic vocabulary and a variable number of local vocabularies was to remain a constant throughout the history of Islamic art.

The middle period in the development of Islamic art extends roughly from the year 1000 to 1500, when a strong central power with occasional regional political independence was replaced by a bewildering mosaic of overlapping dynasties. Ethnically this was the time of major Turkish and Mongol invasions that brought into the Muslim world new peoples and institutions. At the same time, Imazighen (Berbers), Kurds, and Iranians, who had been within the empire from the beginning of Islam, began to play far more effective historical and cultural roles, shortlived for the Kurds, but uniquely important for the Iranians. Besides political and ethnic confusion, there was also religious and cultural confusion during the middle period. The 10th century, for example, witnessed the transformation of the Shi‘ite heterodoxy into a major political and possibly cultural phenomenon, while the extraordinary development taken by the personal and social mysticism known as Sufism modified enormously the nature of Muslim piety. Culturally the most significant development was perhaps that of Persian literature as a highly original new verbal expression existing alongside the older Arabic literary tradition. Finally, the middle period was an era of expansion in all areas except Spain, which was completely lost to the Muslims in 1492 with the conquest of the Kingdom of Granada by Ferdinand II and Isabella. Anatolia and the Balkans, the Crimea, much of Central Asia and northern India, and parts of eastern Africa all became new Islamic provinces. In some cases this expansion was the result of conquests, but in others it had been achieved through missionary work.

The immense variety of impulses that affected the Muslim world during these five centuries was one of the causes of the bewildering artistic explosion that also characterizes the middle period. Although much work has been done on individual monuments, scholarship is still in its infancy. It is particularly difficult, therefore, to decide on the appropriate means of organizing this information: by geographical or cultural areas (e.g., Iran, Egypt, Morocco), by individual dynasties (e.g., Seljuqs, Timurids), by periods (e.g., 13th century before the Mongol invasions), or even by social categories (e.g., the art of princes, the art of cities). Thus, the five following divisions of Fatimid, Seljuq, Western Islamic, Mamluk, and Mongol Iran (Il-Khanid and Timurid) art are partly arbitrary and to a large extent tentative. Their respective importance also varies, for what is known as Seljuq art certainly overwhelms almost all others in its importance.

The Fatimids were technically an Arab dynasty professing with missionary zeal the beliefs of the Isma‘ili sect of the Shi‘ite branch of Islam. The dynasty was established in Tunisia and Sicily in 909. In 969 the Fatimids moved to Egypt and founded the city of Cairo. They soon controlled Syria and Palestine. In the latter part of the 11th century, however, the Fatimid empire began to disintegrate internally and externally; the final demise occurred in 1171. But it is not known which of the obvious components of the Fatimid world was more significant in influencing the development of the visual arts: its heterodoxy, its Egyptian location, its missionary relationship with almost all provinces of Islam, or the fact that during its heyday in the 11th century it was the only wealthy Islamic centre and could thus easily gather artisans and art objects from all over the world.

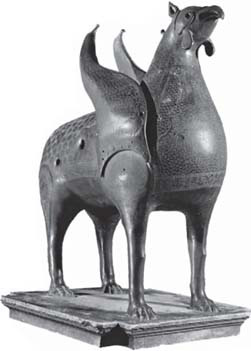

Bronze griffin, 12th century; in the Museo dell’Opera del Duomo, Pisa, Italy. Scala/Art Resource, New York

The great Fatimid mosques of Cairo—al-Azhar (started in 970) and al-Hakim (c. 1002–03)—were designed in the traditional hypostyle plan with axial cupolas. It is only in such architectural details as the elaborately composed facade of al-Hakim, with its corner towers and vaulted portal, that innovations appear, for most earlier mosques did not have large formal gates, nor was much attention previously given to the composition of the exterior facade. The Fatimids’ architectural traditionalism was certainly a conscious attempt to perpetuate the existing aesthetic system.

Although much less is known about it, the Great Palace of the Fatimids belonged to the tradition of the enormous palace-cities typical of the ‘Abbasids. Mediterranean rather than Iranian influences, however, played a greater part in the determination of its uses and functions. The whole city of Cairo (Arabic: al-Qahirah, meaning “the Victorious”), on the other hand, has many symbolic and visual aspects that suggest a willful relationship to Baghdad.

The originality of Fatimid architecture does not lie in works sponsored by the caliphs themselves, even though Cairo’s well-preserved gates and walls of the second half of the 11th century are among the best examples of early medieval military architecture. It is rather the patronage of lower officials and of the bourgeoisie, if not even of the humbler classes, that was responsible for the most interesting Fatimid buildings. The mosques of al-Aqmar (1125) and of al-Salih (c. 1160) are among the first examples of monumental small mosques constructed to serve local needs. Even though their internal arrangement is quite traditional, their plans were adapted to the space available in the urban centre. These mosques were elaborately decorated on the exterior, exhibiting a conspicuousness absent from large hypostyle mosques.

A second innovation in Fatimid architecture was the tremendous development of mausoleums. This may be explained partially by Shi‘ism’s emphasis on the succession of holy men, but the development of these buildings in terms of both quality and quantity indicates that other influential social and religious issues were also involved. Most of the mausoleums were simple square buildings surmounted by a dome. Many of these have survived in Cairo and Aswan. Only a few, such as the mashhad at Aswan, are somewhat more elaborate, with side rooms.

The Fatimids introduced, or developed, only two major constructional techniques: the systematization of the four-centred “keel” arch and the squinch. The latter innovation is of greater consequence because the squinch became the most common means of passing from a square to a dome, although pendentives were known as well. A peculiarly Egyptian development was the muqarnas squinch, which consisted of four units: a niche bracketed by two niche segments, superimposed with an additional niche. The complex profile of the muqarnas became an architectural element in itself used for windows, while the device of using niches and niche segments remained typical of Egyptian decorative design for centuries. It still is impossible to say whether the muqarnas was invented in Egypt or inspired by other architectural traditions (most likely Iranian). Fatimid domes were smooth or ribbed and developed a characteristic “keel” profile.

Stone sculpture, stucco work, and carved wood were used for architectural decorations. The Fatimids also employed mosaicists, who mostly worked in places like Jerusalem, where they imitated or repaired earlier mosaic murals. Many fragments of Fatimid wall paintings have survived in Egypt. Most of them, however, are too small to allow for making any iconographic or stylistic conclusions, with the exception of the mid-12th-century ceiling of the Cappella Palatina at Palermo. Built by the Norman kings of Sicily, the palace chapel was almost certainly decorated by Fatimid artists, or at least the artists adhered to Fatimid models. The hundreds of facets in the muqarnas ceiling were painted, notably with many purely ornamental vegetal and zoomorphic designs. Stylistically influenced by Iraqi ‘Abbasid art, these paintings are innovative in their more spatially aware representation of personages and of animals. The stunning abstraction of the architectural decoration at Samarra’ tends to give way to more naturalistically conceived vegetal and animal designs; occasionally whole narrative scenes appear carved on wood. Another decorative trend is especially used on 12th-century mihrabs: explicitly complicated geometric patterns, usually based on stars, which in turn generate octagons, hexagons, triangles, and rectangles. Geometry becomes a sort of network in the midst of which small vegetal units continue to remain, often as inlaid pieces. Long inscriptions written in very elaborate calligraphies also became a typical form of architectural decoration.

Ceiling of the Cappella Palatina, Palermo, Sicily. The chapel was built by the Norman kings of Sicily and decorated by Fatimid artists. M. Desjardins/Realities

Coronation mantle of King Roger II of Sicily, gold embroidery and pearls on a red silk ground, 1133; in the Hofburg, Vienna. Courtesy of the Hofburg Kunsthistorisches Museum, Vienna

A clear separation must be made between the decorative arts sought by Fatimid princes and the arts produced within their empire. Little has been preserved of the former, notably a small number of superb ewers in rock crystal. A text has survived, however, that describes the imperial treasures looted in the middle of the 11th century by dissatisfied mercenary troops. It lists gold, silver, enamel, and porcelain objects that have all been lost, as well as textiles. The inventory also records that the Fatimids had in their possession many works of Byzantine, Chinese, and even Greco-Roman provenance. Altogether, then, it seems that the imperial art of the Fatimids was part of a sort of international royal taste that downplayed cultural or political differences.

Ceramics, on the other hand, were primarily produced by local urban schools and were not an imperial art. The most celebrated type of Fatimid wares were lustre-painted ceramics from Egypt itself. A large number of artisans’ names have been preserved, thereby indicating the growing prestige of these craftsmen and the aesthetic importance of their pottery. Most of the surviving lustre ceramics are plates on which the decoration of the main surface has been emphasized. The decorative themes used were quite varied and included all the traditional Islamic ones: e.g., calligraphy, vegetal and animal motifs, arabesques. The most distinguishing feature of these Fatimid ceramics, however, is the representation of the human figure. Some of these ceramics have been decorated with simplified copies of illustrations of the princely themes, but others have depictions of scenes of Egyptian daily life.

Manifestations of nonprincely Fatimid art also included the art of book illustration. The few remaining fragments illustrate that probably after the middle of the 11th century there developed an art of representation other than the style used to illustrate princely themes. This was a more illusionistic style that still accompanied the traditional ornamental one in the same manner as in the paintings on ceramics.

In summary it would appear that Fatimid art was a curiously transitional one. Although much influenced by earlier Islamic and non-Islamic Mediterranean styles, the Fatimids devised new structural systems and developed a new manner of painting representational subjects, which became characteristic of all Muslim art during the 12th century.

During the last decades of the 10th century, at the Central Asian frontiers of Islam, a migratory movement of Turkic peoples began that was to affect the whole Muslim world up to and including Egypt. The dominant political force among these peoples was the dynasty of the Seljuqs, but it was not the only one; nor can it be demonstrated, as far as the arts are concerned, that it was the major source of patronage in the period to be discussed anywhere but in Anatolia in the 12th and 13th centuries. The Seljuq empire, therefore, consisted of a succession of dynasties, and all but one (the Ayyubids of Syria, Egypt, and northern Mesopotamia) were Turkic.