The Islamic world contains a rich tradition of extraordinary literature and visual arts that stretches back for centuries. At various times, these arts have influenced—and been influenced by—Western literary and artistic traditions. Yet most Westerners know as little about Islamic literature and visual arts as they do about Islam itself. Popular works such as The Thousand and One Nights and vague notions of tiled mosques or lavish palaces (frequently derived from Western fiction) are often the extent of Westerners’ knowledge of Islamic arts. Viewing Islamic art through the lens of such works is roughly akin to trying to understand the full scope of Western literature and visual arts through popular romance novels and fairy-tale castles. The approach is neither realistic nor fair.

This unenlightened view was shattered with the tragic events of September 11, 2001, when many Americans replaced their naive notions of the exotic Orient with an outright rejection of a mostly unknown religion and all its worshippers. This attitude may be further exacerbated by the prejudice some feel toward the arts in general, that art has no connection to daily life and that it serves no useful purpose. Yet if those notions are accurate, why are the arts so intimately interwoven with human history? The truth is that the creation and appreciation of art is an integral part of what it means to be human. Tens of thousands of years ago—long before writing existed—people painted pictures on cave walls and carved small figures. Before there was writing, there was spoken language, which storytellers used to create an oral tradition that was an essential means of transmitting the fundamental principles of human society and institutions. The best among them could enthrall audiences with long, complex tales. After the invention of writing, many of these stories and poems were recorded, becoming some of the first works of literature.

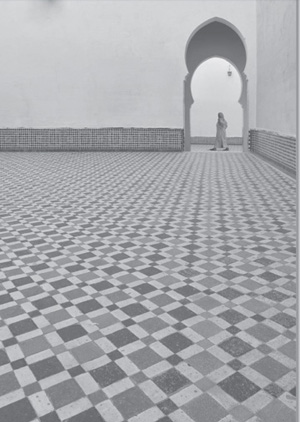

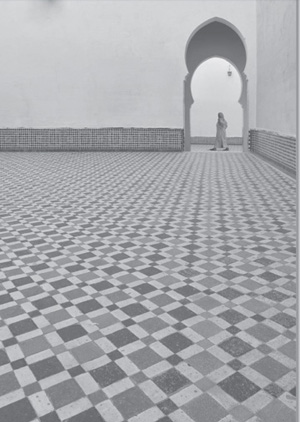

Since that time, peoples around the world have used an immense variety of materials to create innumerable artworks in a myriad of forms and styles. The effort to understand and appreciate these artworks is both a challenging and exhilarating undertaking, not only for the sheer vastness of the task, but also because art serves different purposes at different times and in different cultures. Similarity of form does not necessarily mean similarity of purpose. Ancient Egyptians, for example, placed the organs of the dead in vessels called canopic jars. Westerners today may use similarly shaped vases to hold freshly cut flowers. On the other hand, strikingly different forms may serve similar purposes. Both Quakers and Muslims, for example, needed places to worship and desired to create structures they believed would be pleasing to God, instructive to believers, and in keeping with the tenets of their faith. For Quakers, that often meant plain, simple, unadorned wooden buildings. While Muslims also often worship in spaces without ornamentation or elaboration, enormous, elaborately decorated mosques covered with colourful tiles were considered just as appropriate.

Just as the purposes of art have varied over time and among cultures, so too have the dominant modes. Literature was the preeminent art form of early Islam, and it has retained its high status over the centuries. There are several reasons for this. One is that a solid foundation existed upon which to build Islamic literature. This foundation had been laid in Arabia, Islam’s homeland, long before the birth of the religion’s founder, the Prophet Muhammad. Arabs had developed a highly sophisticated oral literary tradition. One reason for the attention lavished on verbal arts may lie in the migratory lifestyle of the Bedouin, the nomadic desert Arabs. A nomadic way of life imposes certain limits on the art forms a culture develops. Architecture, for example, does not become a major art form, and there is little motivation to create any sort of large-scale art that would be difficult if not impossible to transport easily. Verbal arts, however, are ideal for nomadic cultures.

Poetry held pride of place as an expression of pre-Islamic Arab identity and of communal history. Poets were highly esteemed, and their performances were viewed as powerful tools that could rouse warriors for battle or champion their tribe’s virtues. Elegies—poems in praise of the dead—also constituted a major poetic form. Prose was important, too, particularly the rhymed prose of oracles. Other prose forms included tales of adventure and battle days. One influential prose genre, or form, was the “nighttime conversation.” In this genre, the teller developed the central theme not through storytelling but by leading the listener’s mind from topic to topic through verbal association. Such a complex, subtle prose form could only exist in a society in which spoken language held an elevated status.

Another reason for literature’s preeminent place among Islamic arts is the Qur’an—the Muslim holy book—itself. For Muslims, the Qur’an is God’s own word, recorded in the language chosen by God (Allah)—Arabic. This meant the Qur’an is the supreme and inimitable expression of literary beauty, and Arabic is the vehicle for it. Such a view esteems literature written in Arabic as the highest art form possible.

Yet another reason for literature’s dominance is that therewas a prohibition against images in Islamic art. By the middle of the 8th century, the prohibition had become well-established Islamic doctrine, although the Qur’an itself says nothing one way or the other about images. While the ban on images did not, of course, result in a total lack of visual art, it did help promote the status of literature.

As Islam spread, largely through conquest, the literary traditions and forms of the conquered territories helped to mold Islamic writing. After the Arab conquest of Iran in 640, Persian literature influenced Islamic literature, and Persian became a significant language for Islamic writings. Persian poets introduced epic poetry such as the Shah-nameh (“Book of Kings”), which is a mix of myth, legend, and history. The finest lyric poems were written in Persian. It became traditional to use Persian for court poems, such as roba’iyat. This type of poem is best known in the West through the rather free translations, such as The Ruba’iyat of Omar Khayyam. Iran also introduced new prose genres into Islamic writing, such as the type known as the Mirror for Princes, which used stories to teach rulers proper political practice. Sufis—who practice a mystical form of Islam—produced a wide range of prose writings in genres that were not part of Arabic literary traditions, including letters, collections of conversations by leading sheikhs, mystical commentaries on the Qur’an, treatises on mystical subjects, and biographies. Persian literature also introduced topics that reflected the Sunni and Shi’ite division within Islam. Most Muslims are Sunni. In 1501, when the Safavid dynasty came to power in Iran, many were converted to Islam’s second-largest division, Shi’ism. Persian writers and poets produced works on Shi’ite topics, especially the martyrdom of the twelve imams, the descendants of the Prophet who were leaders of Shi’ism following the Prophet’s death.

Persian culture extended beyond Iran, and Islamic literature written in Persian was produced in northwestern India and what is now Pakistan as early as the 11th century and in what is today Turkey by the 13th century. Islamic writings in languages other than Persian, written by people other than elite poets, also appeared in these regions. In parts of India, ordinary people produced folk poetry interpreting Islamic mysticism in their native languages, while Sufi poets in Turkey wrote verses in various Turkish dialects.

As Islam spread eastward, writers in Central Asia produced works not only in Arabic and Persian, but also in Turkic languages such as Uzbek, Tatar, and Kyrgyz. In East Asia, Islamic literature in Chinese has been found in China and the Philippines. Historical and semimythical tales of Islamic heroes form an interesting part of the Chinese writings.

Islam also spread westward, across North Africa and into Spain, which Muslims invaded in 711. From there, Islamic literature influenced the poetry of French troubadours as well as the romances and heroic tales of western Europe.

Although literature was the preeminent Islamic art form, it was not the only one. The visual arts have played a part in Islamic culture, although their forms and importance have varied across time and across regions. Several factors—some of which have already been mentioned—shaped the development of Islamic visual arts. One was the previously-stated prohibition against images. This ban was based partly on the desire to avoid idolatry and partly on the idea that only Allah can create life and anyone who creates images of living things seeks to rival Allah. Another determinant was the fact that pre-Islamic Arab culture had little art, other than oral poetry and prose, on which to build specifically Islamic visual arts. So, over time, Muslims adapted many of the forms, styles, and subjects of the cultures they conquered.

Wherever their religion spread, Muslims also had the need for a clean, appropriate place for prayer. Thus it was that architecture—especially religious architecture—became the most important Islamic visual art.

The original community that grew up around the Prophet had no special structure for gathering and prayer. Rather, they simply gathered in the Prophet’s house to hear a sermon and to pray. As Islam spread, special buildings called mosques, or masjids, were built for the Muslim community in each conquered area. These buildings were more community centres than religious structures. The faithful not only prayed in them, but also used them to conduct social, political, educational, and religious affairs. Little is known about these early mosques. None survive, and descriptions exist for only a few of the larger ones. These descriptions suggest that Muslims were forced to create a new architectural type because no existing architectural form met their needs. The building type they created was known as a hypostyle structure—a building that has a roof resting on rows of columns. The three most important features of these mosques were the qiblah wall, toward which the faithful prayed; the minbar, or pulpit, for the imam; and the mihrab, a highly decorated niche in the qiblah wall that probably represented the Prophet’s symbolic presence. Where it was practical, early Muslims also converted existing structures of other religions into mosques. The Great Mosque of Damascus was built in the early 700s on a site previously occupied first by a Roman temple and then by an early Christian church. The Roman towers, which were still standing, were used as minarets to call believers to prayer. While the earliest mosques were simple affairs, over time, mosques came to be richly decorated inside and out with marble, mosaics, woodwork, and tile. Incorporated into the decoration were ornate arabesques, which represented the infinity of Allah and had a rigorous mathematical structure that transformed them from images of living things into symbols. The decoration also included calligraphy, which provides yet more evidence of the primacy of the word in Islamic arts.

The other major Islamic architectural form was the palace. There were three basic palace types. The rural complex had a residential unit composed of a square building with an ornate entrance, a courtyard surrounded by a portico, and two floors of rooms. There was also a small mosque and a separate bath with an ornate entrance and a richly decorated hall. Little is known about the other two palace types. The urban palace functioned as both living space and government centre. The palace-city, the third palace type, was exactly what it sounds like—an immense complex, surrounded by a wall, that was so large that it constituted an entire city.

While architecture is a dominant Islamic art, it is supported by a number of less immediately imposing arts. For example, mosques contained carved wooden stands to hold the Qur’an, decorated lamps and candlesticks, and prayer mats. Muslims also produced beautiful metalwork, glass, pottery, and carpets. Sheets of calligraphy adorned walls of homes, and tiles containing calligraphy of a religious nature—such as the name of Muhammed—can be found on many a mosque. Perhaps surprising, in view of the prohibition against images, is the amount of painted imagery of people that survives. Even in Islam’s early days, pictures in private dwellings were tolerated. Later, miniature painting—the images that adorn manuscripts—developed in Iran and spread to India and Turkey. Miniatures appear in books on secular topics and include subjects such as hunts, feasts, romances, myths, and battle scenes.

Much remains to be learned and understood about Islamic art, which became the focus of serious study as an independent field only in the 20th century. This guide to the art, literature, and culture of the Islamic world will serve readers as a useful resource for beginning to understand centuries of creativity, faith, and tradition.