7

What Motivates Dogs?

For many years, dog trainers have been referring to play drives and prey drives to describe their dogs’ interest in games and tendency to show predatory behavior. But these days it’s considered passé to talk about drives, because they bring to mind the over-simplistic notion of a build-up in energy that can be released only by one set of activities. Instead, we are better off referring to attention (Are you listening to me?), salience (Do you care?), motivation (Can you be bothered?) and satiation (Have you had enough?). Of these, motivation is probably the most important—just ask any trainer of birds in a free-flight show, birds that can easily flap away into the wide blue yonder. If the birds are not motivated by food (hungry enough) to reach the trained destination (the part of the open-air theater where the food is), they will be motivated by other resources and exit stage left. Animals make decisions based on their motivation, experience and prediction of the likely consequences of their actions. In this chapter we’ll look at ways to develop and harness motivation.

CHEW ON THIS

Some trainers tell me that they can work out what their animals are thinking. These are the people who claim to “reward the thought.” But as an ethologist, I study behaviors and maintain that you can only reward behaviors that you can see. “Thinking is a behavior,” I hear you say. True, but a completely covert one. There may well be behavioral cues that suggest an animal is processing information (thinking), but until we understand animal cognition more fully and can begin to record images of brain function in unrestrained animals, we need to avoid making incorrect guesses and instead focus on the animal’s behavior. By doing so, we can pick up subtle indications that the animal is about to perform the desired response, and we can certainly reward that. Indeed, the best trainers use such movements—that speak of intention—as the starting point in their shaping programs. Reward the first suggestion of a desirable response, and you’re more likely to eventually get the complete response.

What’s in a name?

Humans use names to identify and address one another and surnames specifically to show the relationship between family members. Feral Cheryl and her pack never use names. They recognize other sorts of labels that they associate with their friends and enemies. These labels can be current, such as the color and shape of the dog running towards them, or retrospective, for example, the smell of the spot where significant others have been lying.

When a breeder gives a litter its pedigree names, she is making a log of the kennel name and often borrowing aspects of the parents’ names to create an extravagant tag, usually sprinkled with a few superlatives. Thus we get names such as Kobelco My Heart. Of course, the dogs themselves are blissfully unaware of such hefty titles. When you give your new pup a name you are hoping to capture the character or temperament of the dog you want to own (e.g., Betty). Clearly, the dog is still none the wiser. In contrast, the nickname(s) your dog ends up attracting reflect the character or temperament of the dog you are beginning to know (Botty, Botswana, Betty-Lorraine, Bettina and Badness).

We use names to get the dog’s attention, as a prefix to issuing a command. So, what does the name actually mean to the dog? It can mean: Pay attention to the human because the noises he is about to make may well be relevant to me, or Return to the human because she has become relevant to me. For some unfortunate dogs, they can mean Stop what you are doing! and even It’s time to hide! I am reminded here of Harold, a very lovable pug I knew, who, when called before bedtime, would hide under the kitchen table because the bed was outside and he detested being put out. The unremarkable things about Harold were that, like most pugs, he was lovable and had a horribly convoluted upper airway, meaning that he made a great deal of breathing noise. The remarkable thing about Harold was that when called, just prior to lights-out, he would not only hide but would appear to hold his breath as if he was aware of the respiratory racket he was making and the way in which this increased his chances of being sprung. Did this mean he was cognitively self-aware? Possibly—although it could also mean that at some stage he had simply learned that changes in his breathing pattern delayed his banishment.

Do I have your attention?

Generally, owners value their dog’s ability to pay attention. For example, a recent study showed strong correlations between owners’ rankings of attention, intelligence and obedience. In most domestic contexts, dogs need attention skills to deal with complex social interactions. Similarly, deficits in attention skills may jeopardize dog- human bonds and explain some unwelcome behaviors. Interestingly, this is set against a background of research, notably by Alex Horowitz, with her landmark study of dogs at play. This indicates that dogs adjust their behavior depending on whether they have their playmate’s attention. They use attention-getting strategies such as barking, barging or accidentally-on-purpose dropping toys, chiefly when the intended recipient is looking away. This finding suggests that dogs may recognize the importance of eye contact not only with dogs but also with humans. It is supported by strong evidence that dogs look at humans (preferably their owners) when faced with a puzzle. However, recent Japanese studies indicate that, when they respond to our commands, dogs are focusing on our head direction more than our gaze.

How does your dog react when you say Hello? The intonation of Hello! when you greet a visitor at home is quite different to the tone you use for the dog when greeting him. If you don’t believe me, try it out. When you and your dog have a spare moment and no one is around, look away from him and say Hello! as if you are saluting a welcome guest. You will notice that he looks for the newcomer. This contrasts sharply with the response he makes when you look in his general direction and say Hello! in the regular voice you use to greet him. The tone makes all the difference and can inform the dog of the relevance of what you’re saying. It can also tell a dog when you are in a bad mood and when you are worth avoiding. Upbeat tones used when issuing commands are more effective than dull ones. By the same token, it pays never to utter a dog’s name in an angry tone because you want only good associations with this word. Adhering to this maxim can make all the difference when calling a dog in an emergency, as when it is in danger.

It may sound trite, but to get a dog’s attention you must be relevant to him. A dog that has learned the cues that herald a walk with its owner is reliably excited because he seems to know that the walk is all about him. You have become more relevant to him because you are making resources available. Good handlers get the maximum effort from their dogs effortlessly. They engage with their dogs with tact and strategically placed energy to get their attention. As John Rogerson, the legendary British dog behaviorist, insists, “He who controls the games controls the dogs”—more of this later. Good trainers not only control their dogs but also create situations that allow their dogs to offer the desired response. For example, if they want a dog to pick up a certain item such as a set of keys they remove all other distractions (leashes, shoes, bags, and so on) when first training the response. Regardless of how good they are at making the desired response easy for the dog, even the stealthiest trainers have to put the shaped responses under stimulus control. This means that the dog offers the response every time the command is issued, and only once the command is issued. For this step in the training process, trainers must have their dog’s attention.

The average dog in the average home isn’t being addressed most of the time and so quickly learns to pay little heed to most human voices. He knows that he has a role in certain circumstances and that this is when humans are most likely to call him. For example, he takes the floor when someone comes to the door, and why wouldn’t he take this role seriously? He has evolved to alert the pack to the approach of incoming traffic, and, what’s more, he usually gets the pack’s undivided attention when he starts barking.

Inside the house the dog is a sitting target for incoming stimuli, and, although he can move around his enclosure, he is at the mercy of the owner making fundamental changes such as leaving or returning home. On a less profound level, the owner continues to have an effect on the dog by simple activities such as switching on lights (that can influence day-length as perceived by the dog), turning off the television (which can be a source of barking dogs that suddenly appear in the living room and leave just as quickly, to be replaced by a human voice delivering a laundry detergent commercial), and producing cooking odors (that so rarely fulfill their promise because they hardly ever become morsels in the dog bowl).

Tapping into the joys of a walk

The sights, sounds and smells on a walk may be more predictable but nonetheless exciting. When off the leash, a dog can choose to approach them or avoid them. A dog on a walk with his owner might think that he has the human’s undivided attention and can exercise some autonomy. This is often very different from how things are at home. Think about the way dogs must fit into a regular human home when they are not the chief focus of attention, which is most of the time for most dogs. So part of the fun of a walk relates to control and who is walking whom. A lack of control of one’s environment is generally associated with poor welfare. So being in control in these ways allows the dog to enjoy itself as much as it ever can.

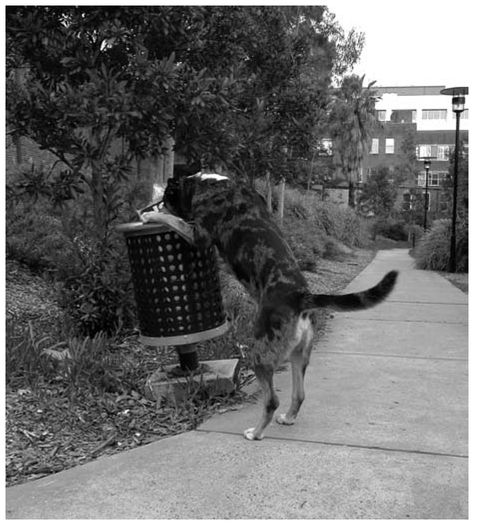

Being left alone at home doesn’t induce the same lack of control as being at home with the pack. It is far, far worse. Only certain, especially valued members of the pack initiate walks—they are the humans. Without them the house has no walks to offer. What’s worse, all those barely hidden resources that the dog knows are there could so easily be plundered by the individuals most likely to know their whereabouts . . . his own social group. New alliances could be formed without the dog being factored in or included. I’m not suggesting that these things consume the minds of home-alone dogs; rather, I am underlining why it shouldn’t surprise us that so many dogs do whatever they can to be taken with their pack for a walk.

What we call a walk should more accurately be labeled an-adventure-window-shopping-social-sporting-sex tour. We see so many dogs turning themselves inside out at the prospect of such a daily romp. And why wouldn’t they? For dogs, hope springs eternal. Admittedly, there are those exceptionally rare dogs that don’t seem to enjoy themselves when out on a leash. These have most probably learned that there is little they can do to exercise choice while on the leash and, as such, are examples of learned helplessness. Some critics have said that some guide dogs seem like this.

Generally, dogs give each walk the benefit of the doubt and set off with absolute optimism, each departure an adventure in the making. They seem convinced that a walk on a rainy day is not such a good idea only when they feel the raindrops on their heads. Small wonder then that they get excited the moment promising hints start being dropped. Slippers are dispensed with, coats are reached for, and keys are rattled—all excellent portents of an imminent door opening. And then, the all-important confirmation: the sound of the leash.

Woe betide all those owners who fail to look at their dogs when these cues are dropped, for they are missing the opportunity to work with a highly motivated dog. Not an easy dog to train so much as an exciting dog to train. Not a steady obedient animal but one that is determined to get its reward. As the keepers of the reward, owners are beautifully placed to wait for exactly the response that they require. But how many of them can bear to waste a moment studying their dogs? After all, they just want the yelping, leaping, squirming and scratching to stop. And so what if the yelping, leaping, squirming and scratching are replaced by concerted pulling on the leash . . . who cares? These are the owners who clip the leash on and do exactly what the dogs are telling them to do: start the bloody walk! And next time the yelping, leaping, squirming and scratching are as bad as ever. And if owners try to prove they are stronger than the dog and able to control it and enforce a sit, the yelping, leaping, squirming and scratching just get worse. As we’ll see in chapter 9 (in which we discuss extinction), when rewards are withheld, things almost always get worse before they get better.

USING A CLICKER

We will look at traditional clicker training and its use in combination with food rewards in much more depth in chapter 10 (The Dogs of Opportunity). Briefly, trainers use a clicker device as a secondary reinforcer by training a dog to associate its sound with food.

Pushing down on a backside to enforce a sit hardly ever works in a hyped-up dog anticipating exercise. Leash tension is the same—it simply gives the dog something to push against. Sarah Whitehead, a leading canine behaviorist from Berkshire in the UK, introduced the term “hands-off training” to emphasize the need for guiding and drawing out good responses (true education) rather than forcing our dogs to conform with the hands-on pressure of leashes and the various gadgets that can be clipped to them. The key here is to tap into the motivation and use a clicker to tell the dog it has done the right thing. The reward in this case is the one thing the dog is extremely motivated to get: a walk. So, owners should click and start the walk as soon as they see the slightest improvement over the previous day (calmness, more sitting, less barking). Using the clicker whenever there is improvement in the dog’s behavior can help the owner’s timing and reduce the dog’s frustration because it acts as a promise of a reward to come. In this way the clicker can contain some of the excitement at the prospect of the door opening because it tells the dog that the point of door opening has arrived.

What keeps a dog motivated?

A dog’s values can be innate or learned. Innate values dictate the games a breed might prefer to play, which is why most Rottweilers love tug-of-war games and most collies love chase games. Meanwhile, learned values can be the result of previous challenges: A dog that one day feared water may become a rapid convert once it has learned that the fear of being cold and wet is outweighed by the joy of floating.

Success breeds success. So if a dog has managed to get a resource it will inevitably be reinforced for the behavior that brought about the success. On the other hand, disappointment can sometimes seem to demoralize a dog by training it to bow out of games it will most likely lose. Admittedly, defeatism is more common in humans than in dogs, and most dogs have the true Olympic spirit: taking part being more important than actually winning.

CHEW ON THIS

Until recently it was believed that constant loss in competitive games of possession, such as tugs-of-war, might successfully demote dogs that assert themselves during play. Fresh evidence suggests that winning all games of possession does not affect other aspects of dog behavior, such as status seeking. However, one shortcoming of this study was that it looked at only one breed—the golden retriever—a breed that may be innately motivated to keep holding onto articles, regardless of success or failure.

Dogs swiftly learn that sitting can brings food rewards, adoring visual contact, and petting. Sitting is a small price to pay for such reinforcers. Sometimes the motivation is less obvious. Old, lame dogs will still chase balls even though their bodies are telling them to kick back and let the youngsters get to the ball first. The pain of the pursuit is overcome by the thrill of the chase. In the same way, dogs that chase cars may stop running as soon as the car stops. They enjoyed the running more than the grabbing of their prey.

Sometimes engaging in a given behavior can have competing—attractive and aversive—outcomes. Dogs that win fights, kill rats or defend their food successfully—even if that means having to pay a cost in terms of pain (for example, bites to the face)—will all do so more readily in the future. So, even though they had to pay a cost, they were reinforced by the pleasure of retaining the reward or possibly even the challenge itself.

The other motivator that is easily overlooked is the element of surprise. Recent studies have shown that dogs, like human infants, seem to respond to unexpected events by paying more attention to them. Rewards that come as a surprise seem somehow more valuable than those that dribble into a dog’s life predictably. Let’s face it: Some owners can be dreadfully predictable with their dogs. Some are downright dull. Others can be full of enjoyable surprises, and while we need to strike the balance between being exciting and consistent, it’s easy to see why dogs adore owners that inspire them to live life as an adventure. Apart from being a consistent source of food, these owners also make so much magic happen. They can turn on taps, open doors, drive cars and find annoying grass seeds lodged in chest fur. An attentive owner is a highly valued resource—the dog’s mobile opportunity shop. We’ll look at other ways humans can coach dogs without seeking their companionship when we explore the world of the working dog in chapter 15.

For a dog, novelty is one of the most important attributes of any toy. So finding your dog a playmate who does not necessarily become a permanent fixture is a really great way to keep him entertained. Arranging for a backyard buddy is often a better way of providing play and companionship than buying a second dog of your own.

Changing motivation

Knowing what will excite your dog is to know what makes him tick. Dogs thrive on activity, and truly inspiring humans are fun to be with, not least because they are a source of action. This explains why dogs owned by slobs may appear disloyal when exposed to more active, energetic and therefore interesting folk. We have all seen dogs that come in from a day’s activity and seem to switch off completely and sleep on until the cue that reliably marks their departure the next day. They have developed a rhythm that matches their owner’s. The team leader dictates what happens and when. This combined with dogs’ behavioral flexibility means that, even though they are most active during daylight hours, these dogs are not necessarily victims of the light-dark cycle. If, for example, they are owned by those who hunt at night (yes, I am thinking of those hunters who, some might say unsportingly, use flashlights to dazzle their prey and so rely on pitch darkness to maximize the blinding effect), the dogs will do the same thing but in reverse so that they conserve their energy by sleeping through the day.

Does the change of seasons affect motivation?

Seasonality can certainly affect behavior and motivation. For example, owners of intact bitches are acutely aware of the seasonal onset of estrus, with its associated shift in motivation and priorities. Once domestic bitches are mature, they cycle twice a year, unless they are Basenjis (the ancient African breed that seem to underline their famed primitiveness by cycling with the same frequency as all wild Canidae). This side-effect of the process of domestication has enabled dog breeders to select breeding stock more frequently than, say, zoological park curators, who can select from only one litter per year.

CHEW ON THIS

Seasons had a profound impact on the availability of food, warmth and comfort for Uncle Wolf. To a lesser extent, some modern dogs are also affected by the seasons. Any vet will confirm that dogs that are allowed indoors are more likely to shed their hair to some extent throughout the year. We aren’t clear what causes this shift from the annual shedding of the winter coat in spring that is seen in outdoor dogs, but it’s most likely due to the controlled environment of indoors. The two prime candidates are heating and lighting. Of these, the more likely is lighting, since detecting changes in day-length is how Feral Cheryl’s body works out that the seasons are changing. Natural day-length shifts are virtually obliterated by artificial lighting. In other words, artificial lights easily confuse the biological clocks of animals as long as they are bright enough. Breeders of Thoroughbred horses use this phenomenon to bring their mares into season early. Dogs that shed their coats throughout the year provide evidence of exactly the same effect. Most owners find that if they exercise their dogs more, they notice less shedding. This could be either because so many hairs are lost during exercise or because the dogs are being exposed to more natural light and so are able to set their expectations of daylight to match. The artificial light they are exposed to in the evenings (and to a lesser extent in the mornings) hardly registers by comparison.

The rebound effect when motivated behavior is restricted

Abstinence from a normal behavior rarely causes it to disappear from the animal’s repertoire. On the contrary, most behaviors can be made more valuable and so more probable by restricting the dog’s access to them. A dog that has been confined to a small space may stretch far more than usual, and if he has been wearing a muzzle he may yawn more than ever. The welfare implications of preventing behaviors with an internal motivation can be profound. They involve frustration and distress. In active copers, these manifest as redirected or so-called displacement behaviors such as self-mutilation. In passive copers, they may take the form of apathy and lethargy.

Behaviors that are prompted solely by a particular stimulus are reasonably predictable. For example, sunlight that wakes a dog might make it stretch and yawn. However, many behaviors don’t have one simple external trigger—they are caused by a combination of internal changes and external conditions. Behaviors with an internal motivation have welfare implications because they can help us understand what opportunities and resources dogs miss most. Many dogs perform a highly motivated behavior more often once they are free to do so after a period of being prevented from doing so. Ethologists call this a post-inhibitory rebound. Behaviors that show a post-inhibitory rebound reflect behavioral needs rather than physiological needs.

A useful example of post-inhibitory rebound comes from car journeys. The period of confinement in the back of a vehicle without much movement is tolerated by most dogs without complaint. However, as soon as the door is opened and they are given chance to stretch their legs, most fit dogs will trot and canter around. They are doing much more than simply stretching their legs; they are meeting their behavioral need for energetic movement. It’s very simple to harness the same principle in training. For example, the opportunity to indulge in any normal activity will be more rewarding if the dog hasn’t had it for some time.

Revving-up and restraint

Although it might seem mean, reserving rewards until you see an improvement in a particular behavior can be very effective. If you use food in training, it’s worth considering how to whet your dog’s appetite and make the most of tasty tidbits as rewards. Preparing food in front of your dog and then putting it away for half an hour before a training session will always sharpen the dog’s performance.

If you’re using play as a reward, tying up a dog and moving out of its reach before playing with its favorite toy, or for that matter any toy without the direct involvement of the dog itself, is enough to get most playful dogs worked up. But it doesn’t work for all dogs. Why not? Is it possible that some dogs are innately motivated by nothing whatsoever? I reckon this is impossible without there being physical signs such as stunted growth. A pup that is not even motivated by food is destined to be a miserably undernourished juvenile. Thanks to the basic nutritional standards in the cheap commercial dog foods and the widespread use, efficacy and affordability of worming treatments, there are fewer and fewer such animals around these days.

When clients tell me that their dogs are impossible to motivate, I always challenge them to reconsider their assumption. Admittedly some breeds are trickier to motivate than others. Bassets lumber to mind. They are difficult to get revved-up, but not impossible. So what is going on with the dogs labeled impossible to motivate and therefore to train? Apart from variable levels of innate motivation, some dogs simply learn to demonstrate little motivation because it is either never rewarded or, more likely, that all their immediate needs are readily met by their owners (their servants?).

The opposite is true, therefore: dogs that know they must work for the resources they value are much more biddable and more pleasant to be around than those that have never learned to value anything. “Nothing is for free” has become the maxim of behaviorists worldwide as they advocate a shift in the distribution of power within the dog-human relationship. They ask the owners of all their patients to wait for a desirable behavior before giving the dog any primary reinforcer (see page 157). To do so is to put the owner in charge of the resources and help them understand the games dogs play and how dogs learn. This then promotes a better understanding of training principles. Without spelling it out in so many words, good behaviorists teach owners to apply learning theory. In chapters 9 to 12, we will look at the principles of learning theory, but just because I have mentioned the word “theory,” don’t panic. I’ll make it as easily digestible as possible.

Learning when motivation has dropped

The triggers for feeding and drinking lie in the brain’s hypothalamus and are crudely known as “on” and “off” switches. Feeding a dog to bursting point can cause it to temporarily lose its trained responses. Feeding a dog too much dry food can reduce its appetite and knock out some of the crispness and immediacy of its responses. Appetite is linked to the wetness of the mouth. A dog with a dry mouth cannot eat as swiftly as a properly hydrated dog, nor is its motivation to feed as high.

One of the best cues I have in my trainer’s toolkit is “All gone!” It signals to the dog that the opportunities for rewards are over for the time being. Following the principle of non-reward (see chapter 4, where we discuss training discs), it stops them offering responses to get me to throw the ball or pet them or give them a treat. The secret is, as ever, to be consistent. Once you have issued this command, you do not reward spontaneous responses because, in essence, the Op Shop is shut. It is, therefore, a signal for them to relax. Dog trainers should become skilled at identifying when motivation has dropped. Doing so stops them asking for behaviors that the dog isn’t likely to offer. This is helpful because associating inferior or inadequate responses with a command can develop a tendency in the dog to offer these questionable responses in place of those previously perfected.

Conflict of interests

A rabbit running out from cover and across a road is enough to send a dog dashing straight into traffic despite the best efforts of the owner to call him back. Competing goals can leave a dog effectively in a dilemma, at a loss to know what to do. This is known as behavioral conflict. Another example is the dog that hates being groomed. It wants to bite the grooming brush or the hand that holds it but doesn’t want to be aggressive towards the groomer, so it bites its own tail instead. This is a form of redirected behavior. Dogs in behavioral conflict often experiment with various ways to resolve the competing motivation. The chances of it emerging with a desirable response are slim, so it’s best to avoid placing a dog in conflict.

CHOICE CUTS

Dogs make decisions based on their motivation, experience and prediction of the likely consequences of their actions.

Knowing what excites your dog is to know what makes him tick.

To get a dog’s attention, you must be relevant to him.

Upbeat tones used when issuing commands are more effective than dull ones.

Never utter a dog’s name in an angry tone.

Owners who are in charge of all the resources have the most trainable dogs.

Learn to tap into your dog’s enthusiasm for such pleasurable activities as going for a walk.

A dog’s values can be innate or learned.

Dogs love surprises; predictable rewards make life boring.

A period of abstinence can make a behavior more valuable and therefore more probable.

Dogs that have learned to work for their resources are much more fun to be around than those that have never learned to value anything.

Dogs are the great opportunists of the animal kingdom. Their ability to overcome fear of humans in order to scavenge on our scraps may have been pivotal in their domestication.

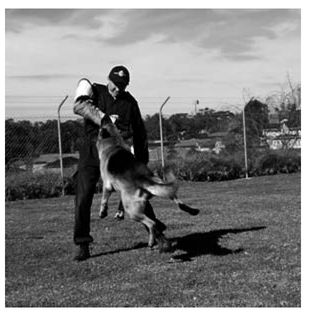

Police dogs performing so-called man work are motivated chiefly by the prospect of a tug-of-war game, not by the need to please their handlers or uphold law and order.

Dogs make decisions based on their motivation, experience and prediction of the likely consequences of their actions.

Dogs make decisions based on their motivation, experience and prediction of the likely consequences of their actions.

Knowing what excites your dog is to know what makes him tick.

Knowing what excites your dog is to know what makes him tick.

To get a dog’s attention, you must be relevant to him.

To get a dog’s attention, you must be relevant to him.

Upbeat tones used when issuing commands are more effective than dull ones.

Upbeat tones used when issuing commands are more effective than dull ones.

Never utter a dog’s name in an angry tone.

Never utter a dog’s name in an angry tone.

Owners who are in charge of all the resources have the most trainable dogs.

Owners who are in charge of all the resources have the most trainable dogs.

Learn to tap into your dog’s enthusiasm for such pleasurable activities as going for a walk.

Learn to tap into your dog’s enthusiasm for such pleasurable activities as going for a walk.

A dog’s values can be innate or learned.

A dog’s values can be innate or learned.

Dogs love surprises; predictable rewards make life boring.

Dogs love surprises; predictable rewards make life boring.

A period of abstinence can make a behavior more valuable and therefore more probable.

A period of abstinence can make a behavior more valuable and therefore more probable.

Dogs that have learned to work for their resources are much more fun to be around than those that have never learned to value anything.

Dogs that have learned to work for their resources are much more fun to be around than those that have never learned to value anything.